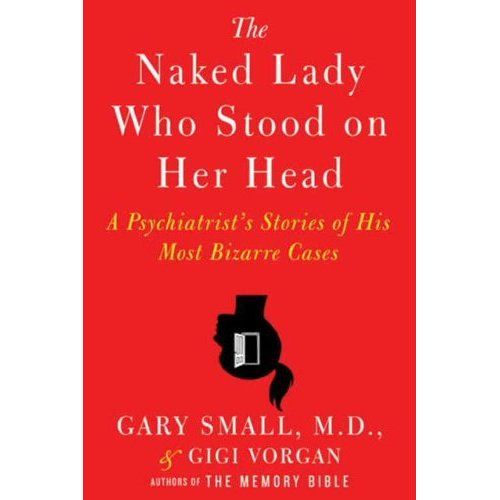

The Naked Lady Who Stood On Her Head ©2010 William Morrow Publishing, all rights reserved.

One of the most captivating books of 2010 was not a gory science-fiction thriller or a gripping end-of-the world page-turner, though its subject matter is equally engrossing and out of the ordinary. It is about somewhat crazy people doing crazy things as seen through the lenses of the man that has been treating them for decades. The Naked Lady Who Stood On Her Head is the first psych ward memoir, a tale of a curious doctor/scientist and his most extreme, bizarre, and sometimes touching cases from the nation’s most prestigious neurology centers and universities. Included in ScriptPhD.com’s review is a podcast interview with Dr. Small, as well as the opportunity to win a free autographed copy of his book. Our end-of-the year science library pick is under the “continue reading” cut.

Dr. Gary Small, Professor of Psychiatry at UCLA's renowned Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior

Gary Small is a very unlikely candidate for the chaos that many of us confuse with a psych ward. Whether it was the frantic psych consults on ER or fond remembrance of Jack Nicholson and his cohorts in One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest, most of us have a natural association of psychiatry with insanity or pandemonium. Meeting Dr. Small in real life is the antithesis of these scenarios. Warm, welcoming, serene and genuinely affable, his voice translates directly from the pages of his latest book. Told in chronological order—starting with a young, curious, inexperienced intern at Harvard’s Massachussetts General Hospital to his tenure as a world-renowned neuroscientist at UCLA—The Naked Lady Who Stood On Her Head feels like an enormous learning and growing experience for Dr. Small, his patients, and the reader.

The scene plays out like a standard medical drama or movie. In the beginning, the young, bright-eyed, bushy-tailed, trepidatious doctor is exploring while learning the ropes on duty. There is, in the self-titled chapter, literally a naked lady standing on her head in the middle of a Boston psych ward. Dr. Small is the only doctor that can cure her baffling ailment, but in doing so, only begins to peel away at what is really troubling her. There is a bevvy of inexplicable fainting schoolgirls afflicting the Boston suburbs. Only through a fresh pair of eager eyes is the root cause attained, a cause that to this day sets the standard for mass hysteria treatment nationwide. And there is a mute hip painter from Venice beach, immobile for weeks until Small, fighting the rigid senior attendings, gets to the unlikely diagnosis. As the book, and Dr. Small’s career, flourishes, we meet a WebMD mom, a young man literally blinded by his family’s pressure, a man whose fiancé’s obsession with Disney characters resurfaces a painful childhood secret, and Dr. Small’s touching story of having to watch as the mentor he introduced at the book’s beginning hires him as a therapist so that he can diagnose his teacher’s dementia. Ultimately, all of the characters of The Naked Lady Who Stood on Her Head, and Dr. Small’s dedication and respect, have a common thread. They are real, they are diverse, and they are us. Psych patients are not one-dimensional figments of a screenwriter’s imagination. They are the brother who has childhood trauma, the friend with a dysfunctional or abusive family, the husband or wife with a rare genetic predisposition, and all of us are but one degree away from the abnormal behavior that these conditions can ignite. In his book, Dr. Small has pulled back the curtain of a notoriously secretive and mysterious field. It’s a riveting reveal, and absolutely worth an appointment. The Naked Lady Who Stood On Her Head has been optioned by 20th Century Fox, and may be coming to your televisions soon!

Podcast Interview

In addition to his latest novel, Gary Small is the author of the best-selling global phenomenon The Memory Bible: An Innovative Strategy For Keeping Your Brain Young and a regular contributor to The Huffington Post (several excellent recent articles can be found here and here). His seminal research on Alzheimer’s disease, aging and brain training has appeared in recent articles in NPR and Newsweek. A seminal brain imaging study recently completed in his laboratory garnered worldwide media attention for suggesting that Google searching can stimulate the brain and literally keep aging brains agile. Dr. Small regularly updates his research and musings on his personal blog.

ScriptPhD.com Editor Jovana Grbić sat down for a one-on-one podcast with Dr. Small and discussed inspiration for the book, current and future aspects of psychiatry, and the role that media and entertainment have played and continue to play in shaping our perception of this important field. Click the “play” button to listen:

In addition to our review and podcast, ScriptPhD.com will be giving away a free signed copy of The Naked Lady Who Stood On Her Head via our Facebook fan page as a little holiday gift for our Facebook fans. Join us and drop a comment on the giveaway announcement for eligibility. Happy Holidays from ScriptPhD.com!

~*ScriptPhD*~

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development.

Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

]]>

The brain's neuron, a remarkably plastic, trainable cell.

Each of the brain’s 100 billion neurons has somewhere in the realm of 7,000 connections to other neurons, creating a tangled roadmap of about 700 trillion possible turns. But thinking of the brain as roads makes it sound very fixed—you know, pavement, and rebar, and steel girders and all. But the opposite is true: at work in our brains are never-sleeping teams of Fraggles and Doozers who rip apart the roads, build new ones, and are constantly at work retooling the brain’s intersections. This study of Fraggles and Doozers is the booming field of neuroplasticity: how the basic architecture of the brain changes over time. Scientist, neuro math geek, Science Channel personality and accomplished author Garth Sundem writes for ScriptPhD.com about the phenomenon of brain training and memory.

Certainly the brain is plastic—the gray matter you wake up with is not the stuff you take to sleep at night. But what changes the brain? How do the Fraggles know what to rip apart and how do the Doozers know what to build? Part of the answer lies in a simple idea: neurons that fire together, wire together. This is an integral part of the process we call learning. When you have a thought or perform a task, a car leaves point A in your brain and travels to point B. The first time you do something, the route from point A to B might be circuitous and the car might take wrong turns, but the more the car travels this same route, the more efficient the pathway becomes. Your brain learns to more efficiently pass this information through its neural net.

A simple example of this “firing together is wiring together” is seen in the infant hippocampus. The hippocampus packages memories for storage deeper in the brain: an experience goes in and a bundle comes out. I think of it like the pegboard at the Seattle Science Center: you drop a bouncy ball in the top and it ricochets down through the matrix of pegs until exiting a slot at the bottom. In the hippocampus, it’s a defined path: you drop an experience in slot number 5,678,284 and

it comes out exit number 1,274,986. How does the hippocampus possibly know which entrance leads to which exit? It wires itself by trial and error (oversimplification alert…but you get the point). Infants constantly fire test balls through the matrix and ones that reach a worthwhile endpoint reinforce worthwhile pathways. These neurons fire together, wire together, and eventually the hippocampus becomes efficient. It’s just that easy. (And because it’s so easy, researchers aren’t far away from creating an artificial hippocampus.)

A crossword puzzle a day keeps the neurons firing away!

Now let’s think about Sudoku. The first time you discover which missing numbers go in which empty boxes, you do so inefficiently. But over time, you get better at it. You learn tricks. You start to see patterns. You develop a workflow. And practice creates efficiency in your brain as neurons create the connections necessary for the quick processing of Sudoku. This is true of any puzzle: your plastic brain changes its basic architecture to allow you to complete subsequent puzzles more efficiently. Okay, that’s great and all, but studies are finding that the vast majority of brain-training attempts don’t generalize to overall intelligence. In other words, by doing Sudoku, you only get better at Sudoku. This might gain you street cred in certain circles, but it doesn’t necessarily make you smarter. Unfortunately, the same is true of puzzle regiments: you get better at the puzzles, but you don’t necessarily get smarter in a general way.

That said, one type of puzzle offers some hope: the crossword. In fact, researchers at Wake Forest University suggest that crossword puzzles strengthen the brain (even in later years) the same way that lifting weights can increase muscle strength. Still, it remains true that doing the crossword only reinforces the mechanism needed to do the crossword. But the crossword uses a very specific mechanism: it forces you to pull a range of facts from deep within your brain into your working memory. This is a nice thing to get better at. Think about it: there are few tasks that don’t require some sort of recall, be it of facts or experiences. And so training a nimble working memory through crosswords seems a more promising regiment than other single type of brain training exercise.

This is borne out by research. A Columbia University study published in 2008 found that training working memory increased overall fluid intelligence. So the answer to this article’s title question is yes, brain training is very real. (Only, there’s lot of schlock out there.) But hidden in this article lies the new key that many researchers hope will point the way to brain training of the future. Any ONE brain training regiment only makes you better at the one thing being trained. But NEW EXPERIENCES in general, promise a varied and continual rewiring of the brain for a fluid and ever-changing development of intelligence. In other words, if you stay in your comfort zone, the comfort zone decays around you. In order to build intelligence or even to keep what you have, you need to be building new rooms, outside your comfort zone. If you consume a new media source in the morning, experiment with a new route to work, eat a new food for lunch, talk to a new person, or…try a NEW puzzle, you’re forcing your brain to rewire itself to be able to deal with these new experiences—you’re growing new neurons and forcing your old ones to scramble to create new connections.

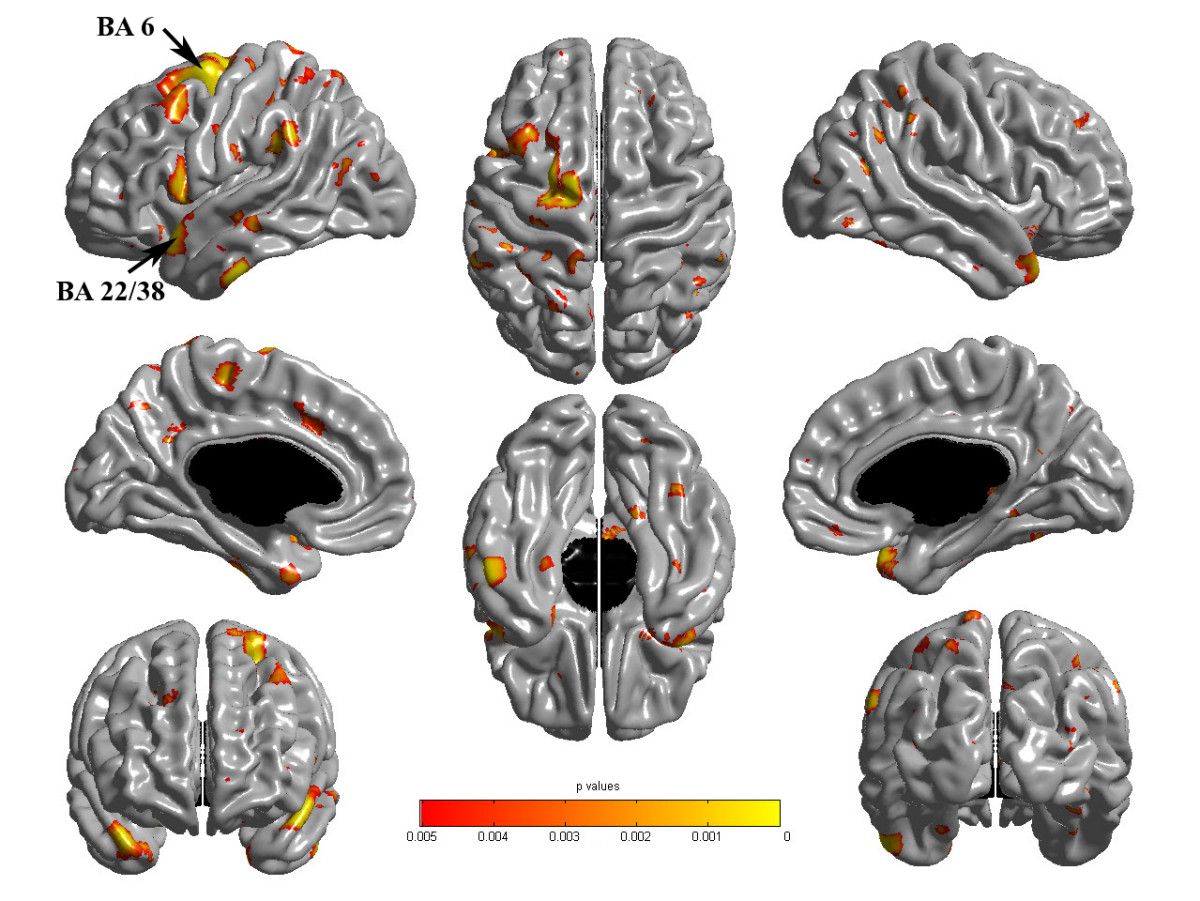

Brain imaging shows growth in cortical thickness for a group of subjects that played Tetris for three months (red and yellow areas). Yes, even playing video games can sharpen your mind!

Here’s what that means for your brain-training regimen: doing a puzzle is little more than busywork; it’s the act of figuring out how to do it that makes you smarter. Sit down and read the directions. If you understand them immediately and know how you should go about solving a puzzle, put it down and look for something else…something new. It’s not just use it or lose it. It’s use it in a novel way or lose it. Try it. Your brain will thank you for it.

Garth Sundem works at the intersection of math, science, and humor with a growing list of bestselling books including the recently released Brain Candy: Science, Puzzles, Paradoxes, Logic and Illogic to Nourish Your Neurons, which he packed with tasty tidbits of fun, new experiences in hopes of making readers just a little bit smarter without boring them

into stupidity. He is a frequent on-screen contributor to The Science Channel and has written for magazines including Wired, Seed, Sand Esquire. You can visit him online or follow his Twitter feed.

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development.

Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

]]>

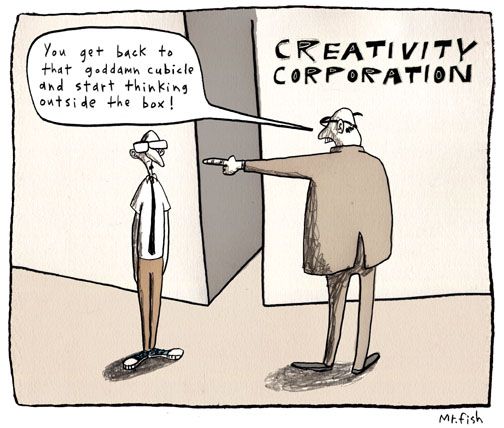

Scientists are becoming more interested in trying to pinpoint precisely what’s going on inside our brains while we’re engaged in creative thinking. Which brain chemicals play a role? Which areas of the brain are firing? Is the magic of creativity linked to one specific brain structure? The answers are not entirely clear. But thanks to brain scan technology, some interesting discoveries are emerging. ScriptPhD.com was founded and focused on the creative applications of science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising, fields traditionally defined by “right brain” propensity. It stands to reason, then, that we would be fascinated by the very technology and science that as attempting to deduce and quantify what, exactly, makes for creativity. To help us in this endeavor, we are pleased to welcome computer scientist and writer Ravi Singh’s guest post to ScriptPhD.com. For his complete article, please click “continue reading.”

Before you can measure something, you must be able to clearly define what it is. It’s not easy to find consensus among scientists on the definition of creativity. But then, it’s not easy to find consensus among artists, either, about what’s creative and what’s not. Psychologists have traditionally defined creativity as “the ability to combine novelty and usefulness in a particular social context.” But newer models argue that these type of definitions, which rely on extremely-subjective criteria like ‘novelty’ and ‘usefulness,’ are too vague. John Kounios, a psychologist at Drexel University who studies the neural basis of insight, defines creativity as “the ability to restructure one’s understanding of a situation in a non-obvious way.” His research shows that creativity is not a singular concept. Rather, it’s a collection of different processes that emerge from different areas of the brain.

In attempting to measure creativity, scientists have had a tendency to correlate creativity with intelligence—or at least link creativity to intelligence—probably because we believe that we have a handle on intelligence. We believe can measure it with some degree of accuracy and reliability. But not creativity. No consensus measure for creativity exists. Creativity is too complex to be measured through tidy, discrete questions. There is no standardized test. There is yet to be a meaningful “Creativity Quotient.” In fact, creativity defies standardization. In the creative realm, one could argue, there’s no place for “standards.” After all, doesn’t the very notion of standardization contradict what creativity is all about?

To test creativity, researchers have historically attempted to test divergent thinking, an assessment construct originally developed in the 1950s by psychologist J. P. Guilford, who believed that standardized IQ tests favored convergent thinkers (who stay focused on solving a core problem), rather than divergent thinkers (who go ‘off on tangents’). Guilford believed that scores on IQ tests should not be taken as a unidimensional measure of intelligence. He observed that creative people often score lower on standard IQ tests because their approach to solving the problems generates a larger number of possible solutions, some of which are thoroughly original. The test’s designers would have never thought of those possibilities. Testing divergent thinking, he believed, allowed for greater appreciation of the diversity of human thinking and abilities. A test of divergent thinking might ask the subject to come up with new and useful functions for a familiar object, such as a brick or a pencil. Or the subject might be asked to draw the taste of chocolate. You can see how it would be very difficult, if not impossible to standardize a “correct” answer.

Eastern traditions have their own ideas about creativity and where it comes from. In Japan, where students and factory workers are stereotyped as being too methodical, researchers are studying schoolchildren for a possible correlation between playfulness and creativity. Nath philosopher Mahendranath wrote that man’s “memory became buried under the artificial superstructure of civilization and its artificial concepts,” his way of saying that that too much convergent thinking can inhibit creativity. Sanskrit authors described the spontaneous and divergent mental experience of sahaja meditation, where new insights occur after allowing the mind to rest and return to the natural, unconditioned state. But while modern scientific research on meditation is good at measuring physiological and behavioral changes, the “creative” part is much more elusive.

Some western scientists suggest that creativity is mostly ascribed to neurochemistry. High intelligence and skill proficiency have traditionally been associated with fast, efficient firing of neurons. But the research of Dr. Rex Jung, a research professor in the department of neurosurgery at the University of New Mexico, shows that this is not necessarily true. In researching the neurology of the creative process, Jung has found that subjects who tested high in “creativity” had thinner white matter and connecting axons in their brains, which has the effect of slowing nerve traffic. Jung believes that this slowdown in the left frontal cortex, a brain region where emotion and cognition are integrated, may allow us to be more creative, and to connect disparate ideas in novel ways. Jung has found that when it comes to intellectual pursuits, the brain is “an efficient superhighway” that gets you from Point A to Point B quickly. But creativity follows a slower, more meandering path that has lots of little detours, side roads and rabbit trails. Sometimes, it is along those rabbit trails that our most revolutionary ideas emerge.

You just have to be willing to venture off the main highway.

We’ve all had aha! moments—those sudden bursts of insight that solve a vexing problem, solder an important connection, or reinterpret a situation. We know what it is, but often, we’d be hard-pressed to explain where it came from or how it originated. Dr. Kounios, along with Northwestern University psychologist Mark Beeman, has extensively studied the the “Aha! moment.” They presented study participants with simple word puzzles that could be solved either through a quick, methodical analysis or an instant creative insight. Participants are given three words then are asked to come up with one word that could be combined with each of these three to form a familiar term; for example: crab, pine and sauce. (Answer: “apple.”) Or eye, gown and basket. (Answer: ball)

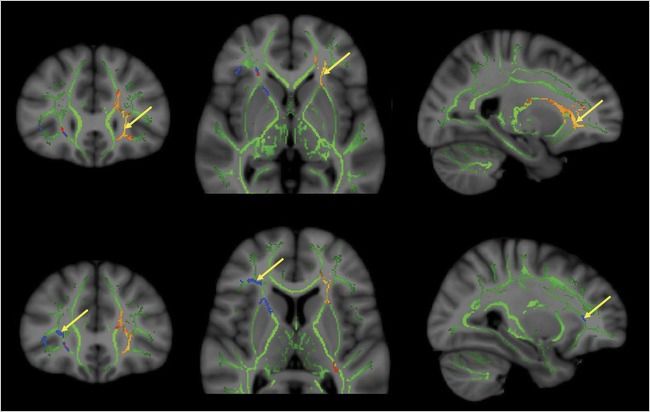

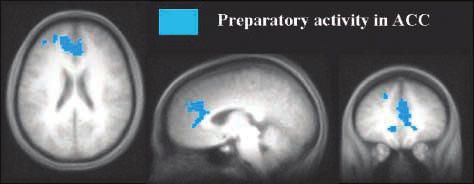

Regions of the brain lighting up in people who "thought about" the answers to a creativity puzzle.

Regions of the brain lighting up for people who had "Aha!" moments to the creativity puzzle.

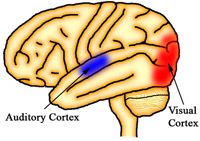

About half the participants arrived at solutions by methodically thinking through possibilities; for the other half, the answer popped into their minds suddenly. During the “Aha! moment,” neuroimaging showed a burst of high-frequency activity in the participants’ right temporal lobe, regardless of whether the answer popped into the subjects’ minds instantly or they solved the problem methodically. But there was a big difference in how each group mentally prepared for the test question. The methodical problem solvers prepared by paying close attention to the screen before the words appeared—their visual cortices were on high alert. By contrast, those who received a sudden Aha! flash of creative insight prepared by automatically shutting down activity in the visual cortex for an instant—the neurological equivalent of closing their eyes to block out distractions so that they could concentrate better. These creative thinkers, Kounios said, were “cutting out other sensory input and boosting the signal-to-noise ratio” to enable themselves retrieve the answer from the subconscious.

Creativity, in the end, is about letting the mind roam freely, giving it permission to ignore conventional solutions and explore uncharted waters. Accomplishing that requires an ability, and willingness, to inhibit habitual responses, take risks. Dr. Kenneth M. Heilman, a neurologist at the University of Florida believes that this capacity to let go may involve a dampening of norepinephrine, a neurotransmitter that triggers the fight-or-flight alarm. Since norepinephrine also plays a role in long-term memory retrieval, its reduction during creative thought may help the brain temporarily suppress what it already knows, which paves the way for new ideas and discovering novel connections. This neurochemical mechanism may explain why creative ideas and Aha! moments often occur when we are at our most peaceful, for example, relaxing or meditating.

The creative mind, by definition, is always open to new possibilities, and often fashions new ideas from seemingly irrelevant information. Psychologists at the University of Toronto and Harvard University believe they have discovered a biological basis for this behavior. They found that the brains of creative people may be more receptive to incoming stimuli from the environment that the brains of others would shut out through the the process of “latent inhibition,” our unconscious capacity to ignore stimuli that experience tells us are irrelevant to our needs. In other words, creative people are more likely to have low levels of latent inhibition. The average person becomes aware of such stimuli, classifies it and forgets about it. But the creative person maintains connections to that extra data that’s constantly streaming in from the environment and uses it.

Sometimes, just one tiny stand of information is all it takes to trigger a life-changing “Aha!” moment.

Ravi Singh is a California-based IT professional with a Masters in Computer Science (MCS) from the University of Illinois. He works on corporate information systems and is pursuing a career in writing.

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development.

Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

]]>

As Comic-Con winds down on the shortened Day 4, we conclude our coverage with two panels that exemplify what Comic-Con is all about. As promised, we dissect the “Comics Design” panel of the world’s top logo designers deconstructing their work, coupled with images of their work. We also bring you an interesting panel of ethnographers, consisting of undergraduate and graduate student, studying the culture and the varying forces that shape Comic-Con. Seriously, they’re studying nerds! Finally, we are delighted to shine our ScriptPhD.com spotlight on new sci-fi author Charles Yu, who presented his new novel at his first (of what we are sure are many) Comic-Con appearance. We sat down and chatted with Charles, and are pleased to publish the interview. And of course, our Day 4 Costume of the Day. Comic-Con 2010 (through the eyes of ScriptPhD.com) ends under the “continue reading” cut!

Comics Design

The visionaries of graphics design for comics (from left to right): Mark Siegel, Chip Kidd, Adam Grano, Mark Chiarello, Keith Wood, and Fawn Lau.

We are not ashamed to admit that here at ScriptPhD.com, we are secret design nerds. We love it, particularly since good design so often elevates the content of films, television, and books, but is a relatively mysterious process. One of THE most fascinating panels that we attended at Comic-Con 2010 was on the design secrets behind some of your favorite comics and book covers. A panel of the world’s leading designers revealed their methodologies (and sometimes failures) in the design process behind their hit pieces, lifting the shroud of secrecy that designers often envelop themselves in. An unparalleled purview into the mind of the designer, and the visual appeal that so often subliminally contributes to the success of a graphic novel, comic, or even regular book. We do, as it turns out, judge books by their covers.

As promised, we revisit this illuminating panel, and thank Christopher Butcher, co-founder of The Toronto Comic Arts Festival and co-owner of The Beguiling, Canada’s finest comics bookstore. Chris was kind enough to provide us with high-quality images of the Comics Design panel’s work, for which we at ScriptPhD.com are grateful. Chris had each of the graphic artists discuss their work with an example of design that worked, and design that didn’t (if available or so inclined). The artist was asked to deconstruct the logo or design and talk about the thought process behind it.

Mark Ciarello – (art + design director at DC Comics)

SOLO, a new release from DC Comics.

Mark chose to design the cover of this book with an overall emphasis on the individual artist. Hence the white space on the book, and a focus on the logo above the “solo” artist.

Adam Grano – (designer at Fantagraphics)

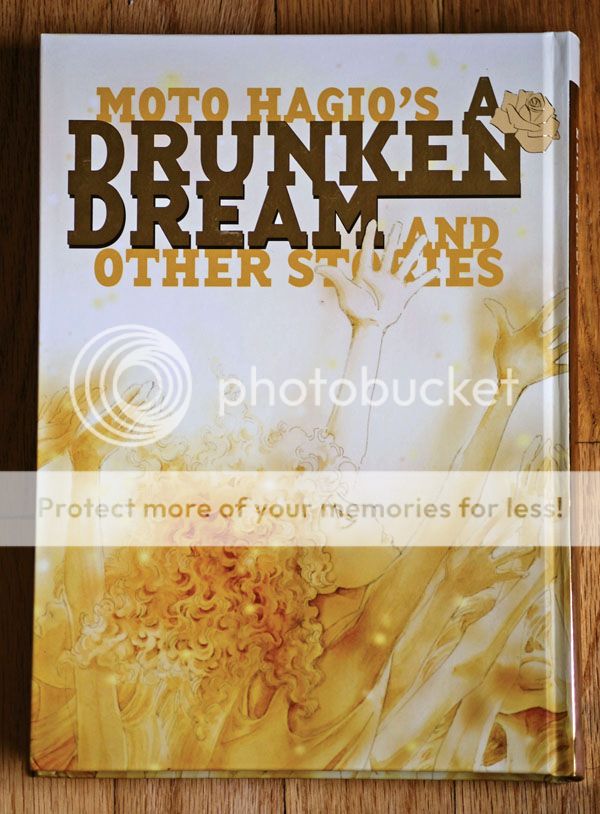

The book cover of A Drunken Dream by Moto Hagio

Adam took the title of this book quite literally, and let loose with his design to truly emphasize the title. He called it “method design.” He wanted the cover to look like a drunken dream.

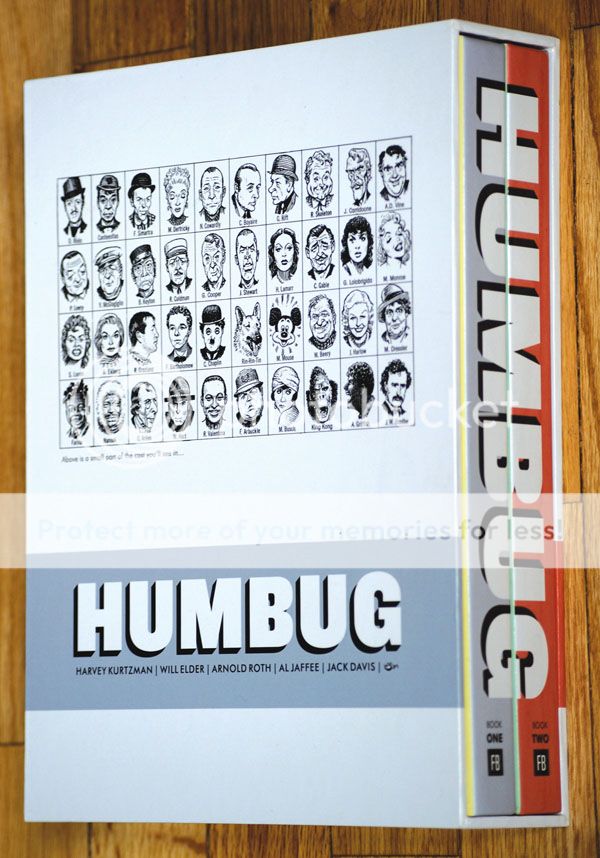

The Humbug collection.

For the Humbug collection, Grano tried hard not to impress too much of himself (and his tastes) in the design of the cover. He wanted to inject simplicity in a project that would stand the test of time, because it was a collector’s series.

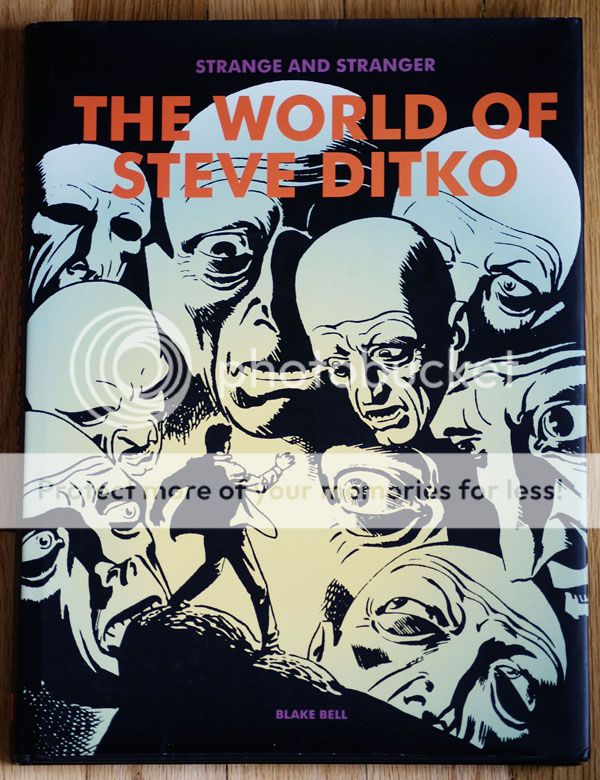

Book cover for The World of Steve Ditko by Blake Bell.

Grano considered this design project his “failure.” It contrasts greatly with the simplicity and elegance of Humbug. He mentioned that everyone on the page is scripted and gridded, something that designers try to avoid in comics.

Chip Kidd – (designer at Random House)

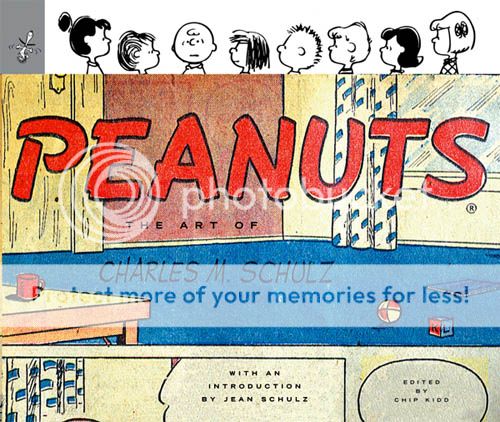

The first Peanuts collection release after Charles M. Schultz's death.

Chip Kidd had the honor of working on the first posthumous Peanuts release after Charles M. Schultz’s death, and took to the project quite seriously. In the cover, he wanted to deconstruct a Peanuts strip. All of the human element is taken out of the strip, with the characters on the cover up to their necks in suburban anxiety.

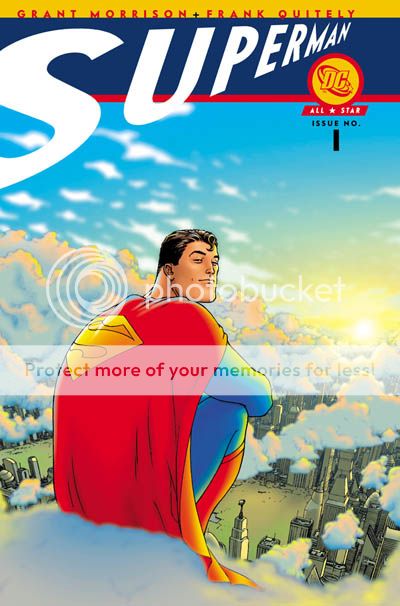

Grant Morrison's Superman.

Kidd likes this cover because he considers it an updated spin on Superman. It’s not a classic Superman panel, so he designed a logo that deviated from the classic “Superman” logo to match.

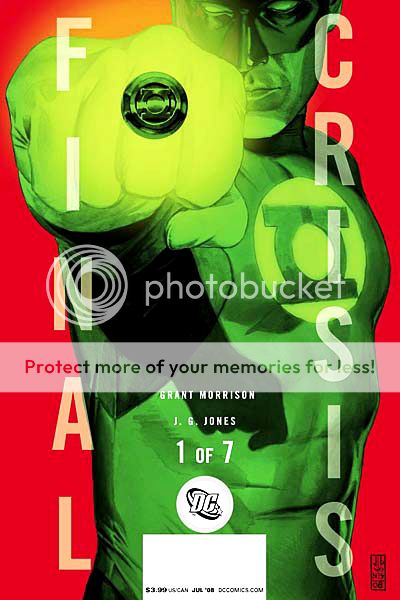

Final Crisis, volume 1, by Grant Morrison and J.G. Jones.

Kidd chose this as his design “failure”, but not the design itself. The cover represents one of seven volumes, in which the logo pictured disintegrates by the seventh issue, to match the crisis in the title. Kidd’s only regret here is that he was too subtle. He wishes he’d chosen to start the logo disintegration progression sooner, as there’s very little difference between the first few volumes.

Fawn Lau – (designer at VIZ)

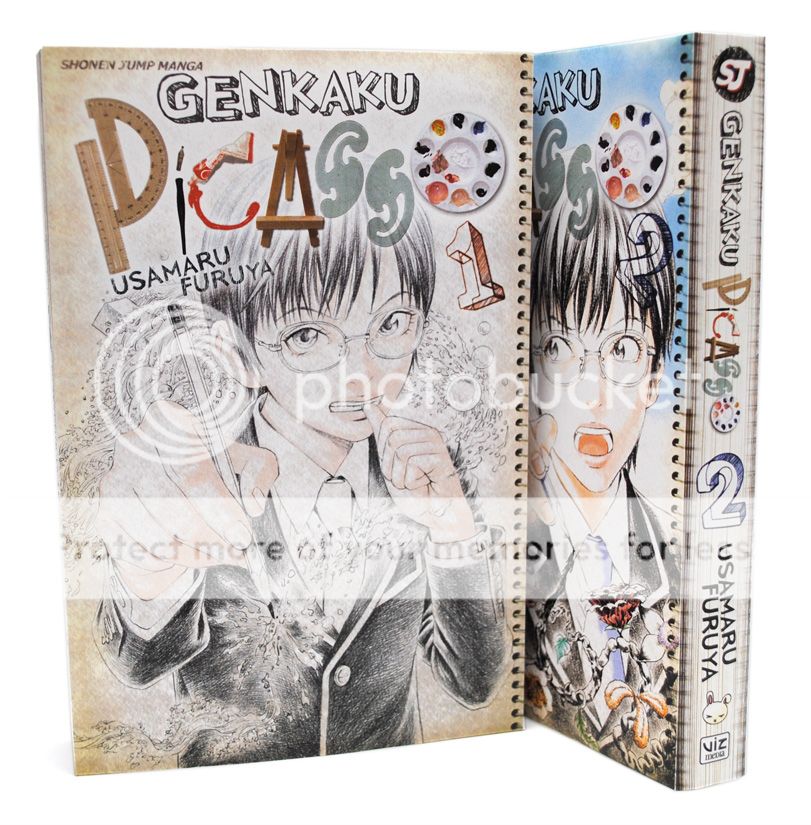

GenKaku Picasso by Usamaru Furuya

Fawn was commissioned to redesign this book cover for an American audience. Keeping this in mind, and wanting the Japanese animation to be more legible for the American audience, she didn’t want too heavy-handed of a logo. In an utterly genius stroke of creativity, Lau went to an art store, bought $70 worth of art supplies, and played around with them until she constructed the “Picasso” logo. Clever, clever girl!

Mark Siegel – (First Second Books)

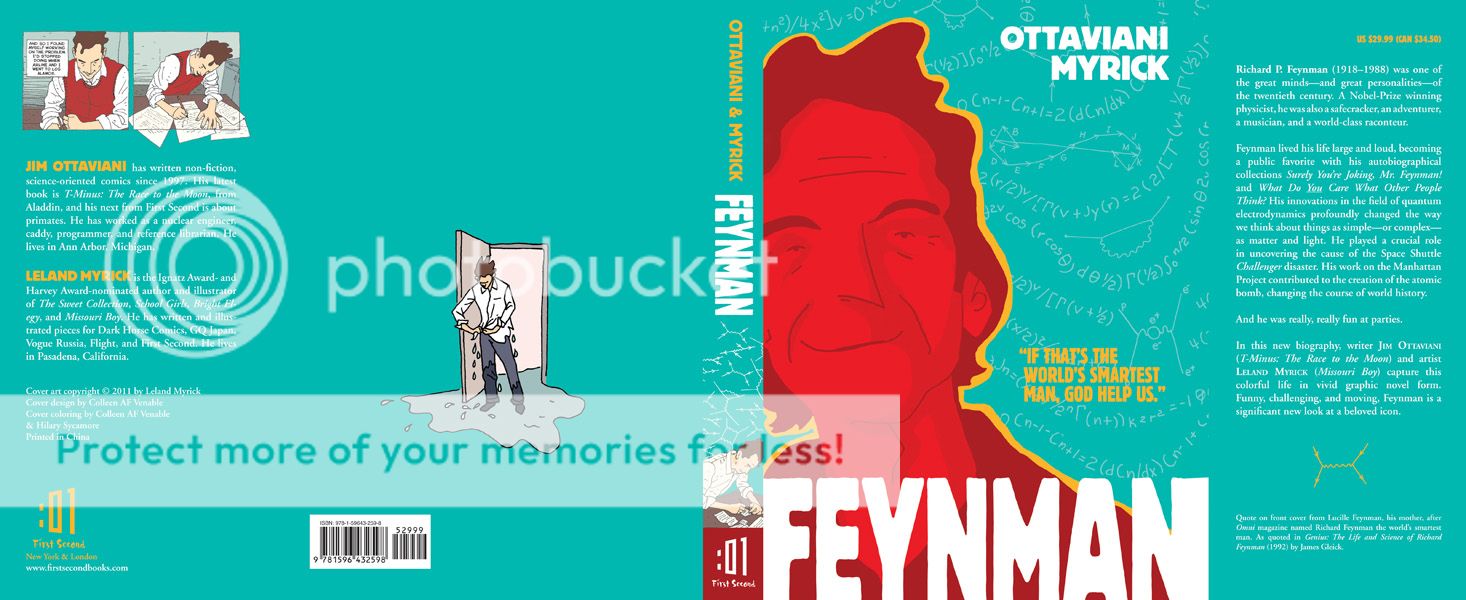

The new biography "Feynman" by Ottaviani Myrick.

Mark Siegel was hired to create the cover of the new biography Feynman, an eponymous title about one of the most famous physicists of all time. Feynman was an amazing man who lived an amazing life, including a Nobel Prize in physics in 1965. His biographer, Ottaviani Myrick, a nuclear physicist and speed skating champion, is an equally accomplished individual. The design of the cover was therefore chosen to reflect their dynamic personalities. The colors were chosen to represent the atomic bomb and Los Alamos, New Mexico, where Feynman assisted in the development of The Manhattan Project. Incidentally, the quote on the cover – “If that’s the world’s smartest man, God help us!” – is from Feynman’s own mother.

Keith Wood – (Oni Press)

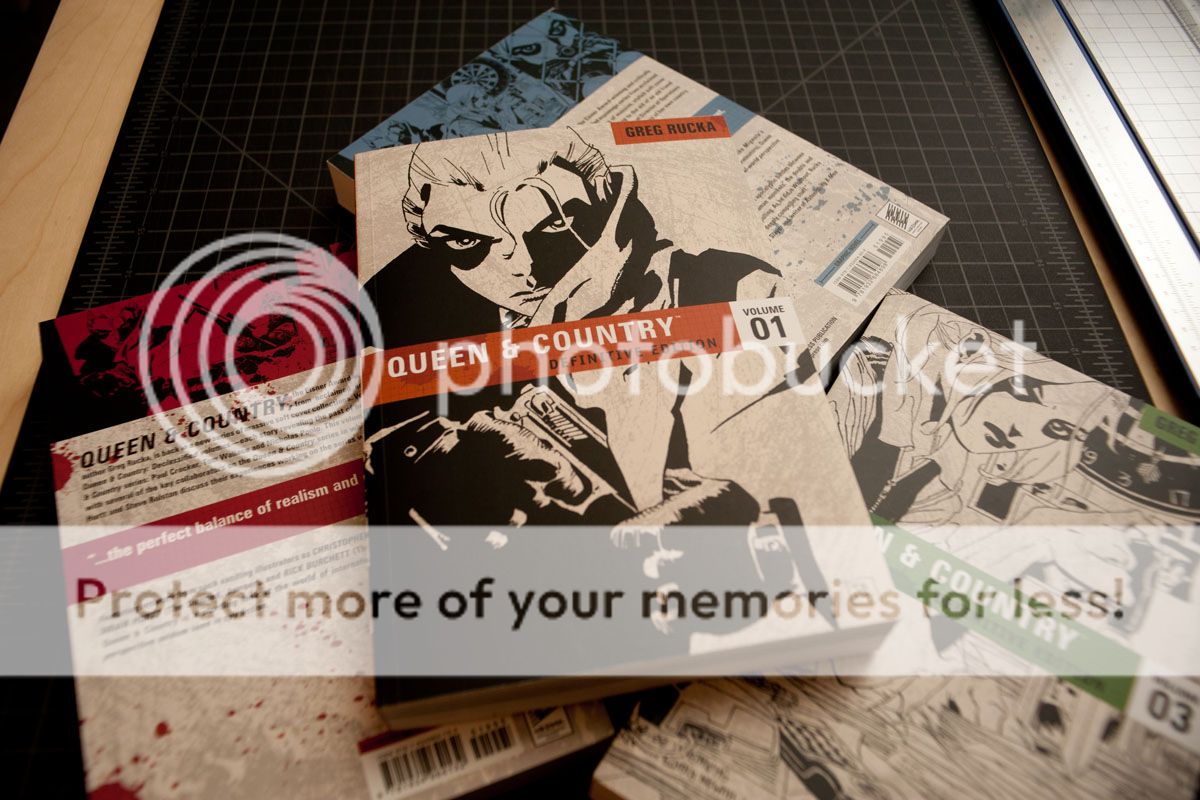

The Queen and Country collection.

Wood remarked that this was the first time he was able to do design on a large scale, which really worked for this project. He chose a very basic color scheme, again to emphasize a collection standing the test of time, and designed all the covers simultaneously, including color schemes and graphics. He felt this gave the project a sense of connectedness.

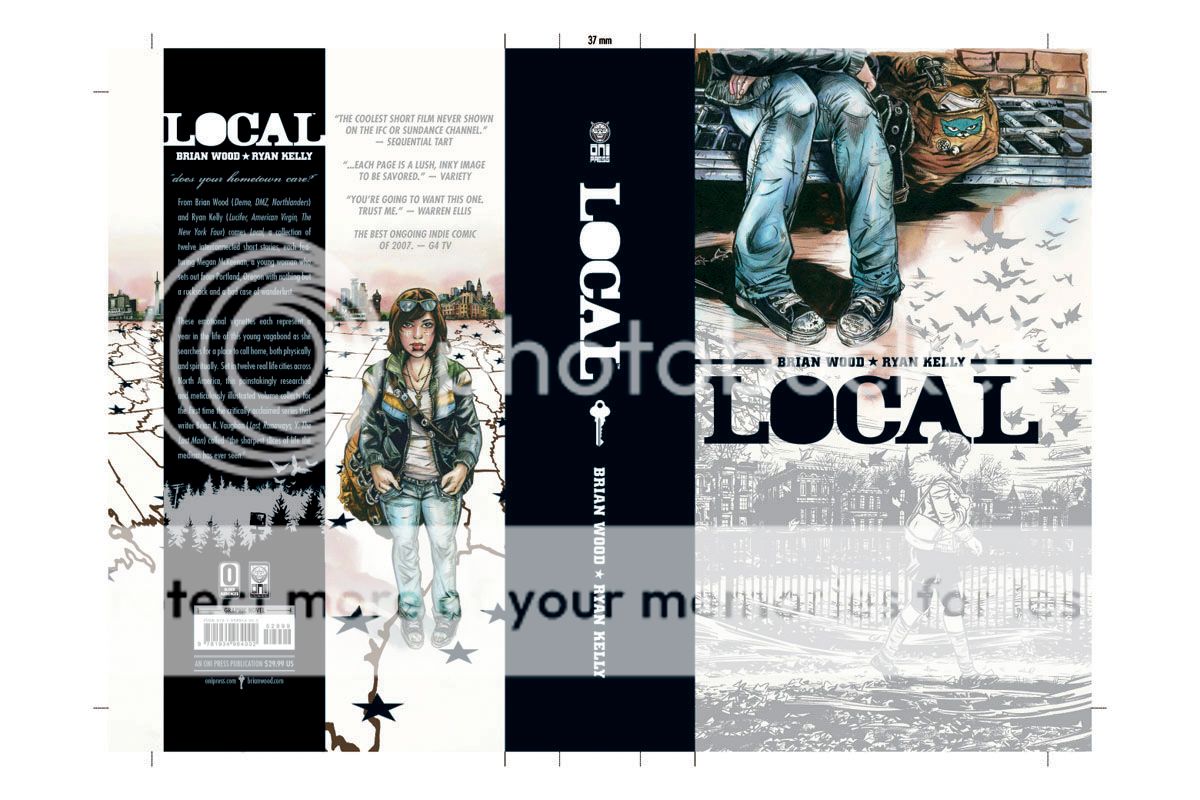

Local by Bryan Wood and Ryan Kelly.

Wood chose a pantone silver as the base of this design with a stenciled typeface meant to look very modern. The back of the cover and the front of the cover were initially going to be reversed when the artists first brought him the renderings. However, Wood felt that since the book’s content is about the idea of a girl’s traveling across the United States, it would be more compelling and evocative to use feet/baggage as the front of the book. He was also the only graphic artist to show a progression of 10-12 renderings, playing with colors, panels and typeface, that led to the final design. He believes in a very traditional approach to design, which includes hand sketches and multiple renderings.

The Culture of Popular Things: Ethnographic Examinations of Comic-Con 2010

Undergraduate and graduate students present their sociology and economics analyses of Comic-Con 2010.

Each year, for the past four years, Comic-Con ends on an academic note. Matthew J. Smith, a professor at Wittenberg University in Ohio, takes along a cadre of students, graduate and undergraduate, to study Comic-Con; the nerds, the geeks, the entertainment component, the comics component, to ultimately understand the culture of what goes on in this fascinating microcosm of consumerism and fandom. By culture, the students embrace the accepted definition by famous anthropologist Raymond J. DeMallie: “what is understood by members of a group.” The students ultimately wanted to ask why people come to Comic-Con in general. They are united by the general forces of being fans; this is what is understood in their group. After milling around the various locales that constituted the Con, the students deduced that two ultimate forces were simultaneously at play. The fan culture drives and energizes the Con as a whole, while strong marketing forces were on display in the exhibit halls and panels.

Maxwell Wassmann, a political economy student at Wayne State University, pointed out that “secretly, what we’re talking about is the culture of buying things.” He compared Comic-Con as a giant shopping mall, a microcosm of our economic system in one place. “If you’ve spent at least 10 minutes at Comic-Con,” he pointed out, “you probably bought something or had something tried to be sold to you. Everything is about marketing.” As a whole, Comic-Con is subliminally designed to reinforce the idea that this piece of pop culture, which ultimately advertises an even greater subset of pop culture, is worth your money. Wassmann pointed out an advertising meme present throughout the weekend that we took notice of as well—garment-challenged ladies advertising the new Green Hornet movie. The movie itself is not terribly sexy, but by using garment-challenged ladies to espouse the very picture of the movie, when you leave Comic-Con and see a poster for Green Hornet, you will subconsciously link it to the sexy images you were exposed to in San Diego, greatly increasing your chances of wanting to see the film. By contrast, Wassmann also pointed out that there is a concomitant old-town economy happening; small comics. In the fringes of the exhibition center and the artists’ space, a totally different microcosm of consumerism and content exchange.

Kane Anderson dressed up in a costume as he immerses himself in the culture of comics fans in San Diego.

Kane Anderson, a PhD student at UC Santa Barbara getting his doctorate in “Superheroology” (seriously, why didn’t I think of that back in graduate school??), came to San Diego to observe how costumes relate to the superhero experience. To fully absorb himself in the experience, and to gain the trust of Con attendees that he’d be interviewing, Anderson came in full costume (see above picture). Overall, he deduced that the costume-goers, who we will openly admit to enjoying and photographing during our stay in San Diego, act as goodwill ambassadors for the characters and superheroes they represent. They also add to the fantasy and adventure of Comic-Con goers, creating the “experience.” The negative side to this is that it evokes a certain “looky-loo” effect, where people are actively seeking out, and singling out, costume-wearers, even though they only constitute 5% of all attendees.

Tanya Zuk, a media masters student from the University of Arizona, and Jacob Sigafoos, an undergraduate communications major at Wittenberg University, both took on the mighty Hollywood forces invading the Con, primarily the distribution of independent content, an enormous portion of the programming at Comic-Con (and a growing presence on the web). Zuk spoke about original video content, more distinctive of new media, is distributed primarily online. It allows for more exchange between creators and their audience than traditional content (such as film and cable television), and builds a community fanbase through organic interaction. Sigafoos expanded on this by talking about how to properly market such material to gain viral popularity—none at all! Lack of marketing, at least traditional forms, is the most successful way to promote a product. Producing a high-quality product, handing it off to friends, and promoting through social media is still the best way to grow a devoted following.

And speaking of Hollywood, their presence at Comic-Con is undeniable. Emily Saidel, a Master’s student at NYU, and Sam Kinney, a business/marketing student at Wittenberg University, both took on the behemoth forces of major studios hawking their products in what originally started out as a quite independent gathering. Saidel tackled Hollywood’s presence at Comic-Con, people’s acceptance/rejection thereof, and how comics are accepted by traditional academic disciplines as didactic tools in and of themselves. The common thread is a clash between the culture and the community. Being a member of a group is a relatively simple idea, but because Comic-Con is so large, it incorporates multiple communities, leading to tensions between those feeling on the outside (i.e. fringe comics or anime fans) versus those feeling on the inside (i.e. the more common mainstream fans). Comics fans would like to be part of that mainstream group and do show interest in those adaptations and changes (we’re all movie buffs, after all), noted Kinney, but feel that Comic-Con is bigger than what it should be.

But how much tension is there between the different subgroups and forces? The most salient example from last year’s Con was the invasion of the uber-mainstream Twilight fans, who not only created a ruckus on the streets of San Diego, but also usurped all the seats of the largest pavilion, Hall H, to wait for their panel, locking out other fans from seeing their panels. (No one was stabbed.) In reality, the supposed clash of cultures is blown out of proportion, with most fans not really feeling the tension. To boot, Seidel pointed out that tension isn’t necessarily a bad thing, either. She gave a metaphor of a rubber band, which only fulfills its purpose with tension. The different forces of Comic-Con work in different ways, if sometimes imperfectly. And that’s a good thing.

Incidentally,

if you are reading this and interested in participating in the week-long program in San Diego next year, visit the official website of the Comic-Con field study for more information. Some of the benefits include: attending the Comic-Con programs of your choice, learning the tools of ethnographic investigation, and presenting the findings as part of a presentation to the Comics Arts Conference. Dr. Matthew Smith, who leads the field study every year, is not just a veteran attendee of Comic-Con, but also the author of The Power of Comics.

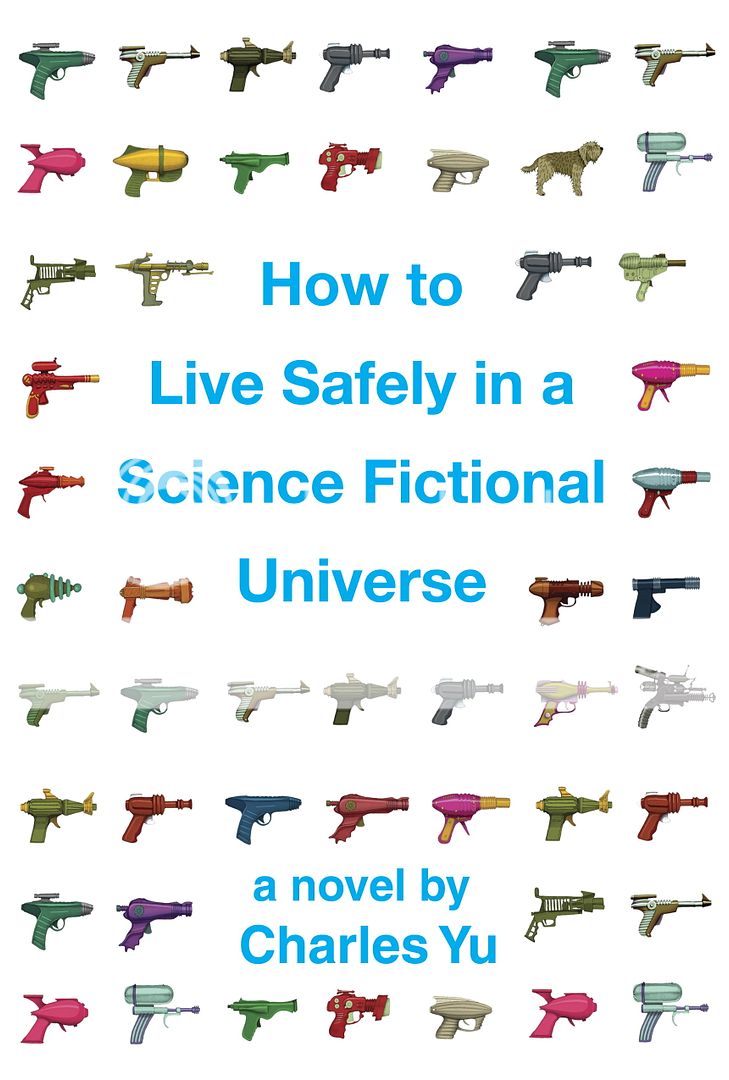

COMIC-CON SPOTLIGHT ON: Charles Yu, author of How To Live Safely in a Science Fictional Universe.

How To Live Safely in a Science Fictional Universe, out in release September 7, 2010.

Here at ScriptPhD.com, we love hobnobbing with the scientific and entertainment elite and talking to writers and filmmakers at the top of their craft as much as the next website. But what we love even more is seeking out new talent, the makers of the books, movies and ideas that you’ll be talking about tomorrow, and being proud to be the first to showcase their work. This year, in our preparation for Comic-Con 2010, we ran across such an individual in Charles Yu, whose first novel, How To Live Safely in a Science Fictional Universe premieres this fall, and who spoke about it at a panel over the weekend. We had an opportunity to have lunch with Charles in Los Angeles just prior Comic-Con, and spoke in-depth about his new book, along with the state of sci-fi in current literature. We’re pretty sure Charles Yu is a name science fiction fans are going to be hearing for some time to come. ScriptPhD.com is proud to shine our 2010 Comic-Con spotlight on Charles and his debut novel, which is available September 7, 2010.

How To Live Safely in a Science Fictional Universe is the story of a son searching for his father… through quantum-space time. The story takes place on Minor Universe 31, a vast story-space on the outskirts of fiction, where paradox fluctuates like the stock market, lonely sexbots beckon failed protagonists, and time travel is serious business. Every day, people get into time machines and try to do the one thing they should never do: try to change the past. That’s where the main character, Charles Yu, time travel technician, steps in. Accompanied by TAMMY (who we consider the new Hal), an operating system with low self-esteem, and a nonexistent but ontologically valid dog named Ed, Charles helps save people from themselves. When he’s not on the job, Charles visits his mother (stuck in a one-hour cycle, she makes dinner over and over and over) and searches for his father, who invented time travel and then vanished.

Questions for Charles Yu

Sci-fi author Charles Yu.

ScriptPhD.com: Charles, the story has tremendous traditional sci-fi roots. Can you discuss where the inspiration for this came from?

Charles Yu: Well the sci-fi angle definitely comes from being a kid in the 80s, when there were blockbuster sci-fi things all over the place. I’ve always loved [that time], as a casual fan, but also wanted to write it. I didn’t even start doing that until after I’d graduated from law school. I did write, growing up, but I never wrote fiction—I didn’t think I’d be any good at it! I wrote poetry in college, minored in it, actually. Fiction and poetry are both incredibly hard, and poetry takes more discipline, but at least when I failed in my early writing, it was a 100 words of failure, instead of 5,000 words of it.

SPhD: What were some of your biggest inspirations growing up (television or books) that contributed to your later work?

CY: Definitely The Foundation Trilogy. I remember reading that in the 8th grade, and I remember spending every waking moment reading, because it was the greatest thing I’d ever read. First of all, I was in the 8th grade, so I hadn’t read that many things, but the idea that Asimov created this entire self-contained universe, it was the first time that I’d been exposed to that idea. And then to have this psychohistory on top, it was kind of trippy. Psychohistory is the idea that social sciences can be just as rigorously captured with equations as any physical science. I think that series of books is the main thing that got me into sci-fi.

SPhD: Any regrets about having named the main character after yourself?

CY: Yes. For a very specific reason. People in my life are going to think it’s biographical, which it’s very much not. And it’s very natural for people to do that. And in my first book of short stories, none of the main characters was named after anyone, and still I had family members that asked if that was about our family, or people that gave me great feedback but then said, “How could you do that to your family?” And it was fiction! I don’t think the book could have gotten written had I not left that placeholder in, because the one thing that drove any sort of emotional connection for the story for me was the idea of having less things to worry about. The other thing is that because the main character is named after you, as you’re writing the book, it acts as a fuel or vector to help drive the emotional completion.

SPhD: In the world of your novel, people live in a lachrymose, technologically-driven society. Any commentary therein whatsoever on the technological numbing of our own current culture?

CY: Yes. But I didn’t mean it as a condemnation, in a sense. I wouldn’t make an overt statement about technology and society, but I am more interested in the way that technology can sometimes not connect people, but enable people’s tendency to isolate themselves. Certainly, technology has amazing connective possibilities, but that would have been a much different story, obviously. The emotional plot-level core of this book is a box. And that sort of drove everything from there. The technology is almost an emotional technology that [Charles, the main character] has invented with his dad. It’s a larger reflection of his inability to move past certain limitations that he’s put on himself.

SPhD: What drives Charles, the main character of this book?

CY: What’s really driving Charles emotionally is looking for his dad. But more than that, is trying to move through time, to navigate the past without getting stuck in it.

SPhD: Both of his companions are non-human. Any significance to that?

CY: It probably speaks more to my limitations as a writer [laughs]. That was all part of the lonely guy type that Charles is being portrayed as. If he had a human with him, he’d be a much different person.

SPhD: The book abounds in scientific jargon and technological terminology, which is par for the course in science fiction, but was still very ambitious. Do you have high expectations of the audience that will read this book?

CY: Yeah. I was just reading an interview where the writer essentially said “You can never go wrong by expecting too much [of your audience].” You can definitely go wrong the other way, because that would come off as terrible, or assuming that you know more. But actually, my concerns were more in the other direction, because I knew I was playing fast and loose with concepts that I know I don’t have a great grasp of. I’m writing from the level of amateur who likes reading science books, and studied science in college—an entertainment layreader. My worry was whether I was BSing too much [of the science]. There are parts where it’s clearly fictional science, but there are other parts that I cite things that are real, and is anyone who reads this who actually knows something about science going to say “What the heck is this guy saying?”

SPhD: How To Live… is written in a very atavistic, retro 80s style of science fiction, and really reminded me of the best of Isaac Asimov. How do you feel about the current state of sci-fi literature as relates to your book?

CY: Two really big keys for me, and things I was thinking about while writing [this book], were one, there is kind of a kitchiness to sci-fi, and I think that’s kind of intentional. It has a kind of do-it-yourself aesthetic to it. In my book, you basically have a guy in the garage with his dad, and yes the dad is an engineer, but it’s in a garage without great equipment, so it’s not going to look sleek, you can imagine what it’s going to look like—it’s going to look like something you’d build with things you have lying around in the garage. On the other hand, it is supposed to be this fully realized time machine, and you’re not supposed to be able to imagine it. Even now, when I’m in the library in the science-fiction section, I’ll often look for anthologies that are from the 80s, or the greatest time travel stories from the 20th Century that cover a much greater range of time than what’s being published now. It’s almost like the advancement of real-world technology is edging closer to what used to be the realm of science fiction. The way that I would think about that is that it’s not exploting what the real possibility of science fiction is, which is to explore a current world or any other completely strange world, but not a world totally envisionable ten years from now. You end up speculating on what’s possible or what’s easily extrapollatable from here; that’s not necessarily going to make for super emotional stories.

Charles Yu is a writer and attorney living in Los Angeles, CA.

Last, but certainly not least, is our final Costume of the Day. We chose this young ninja not only because of the coolness of his costume, but because of his quick wit. As we were taking the snapshot he said, “I’m smiling, you just can’t see it.” And a check mate to you, young sir.

Day 4 Costume of the Day.

Incidentally, you can find much more photographic coverage of Comic-Con on our Facebook fan page. Become a fan, because this week, we will be announcing Comic-Con swag giveaways that only Facebook fans are eligible for.

~*ScriptPhD*~

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development.

Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

]]>

The Vision Revolution by Mark Changizi. ©2010 BenBella Books, all rights reserved

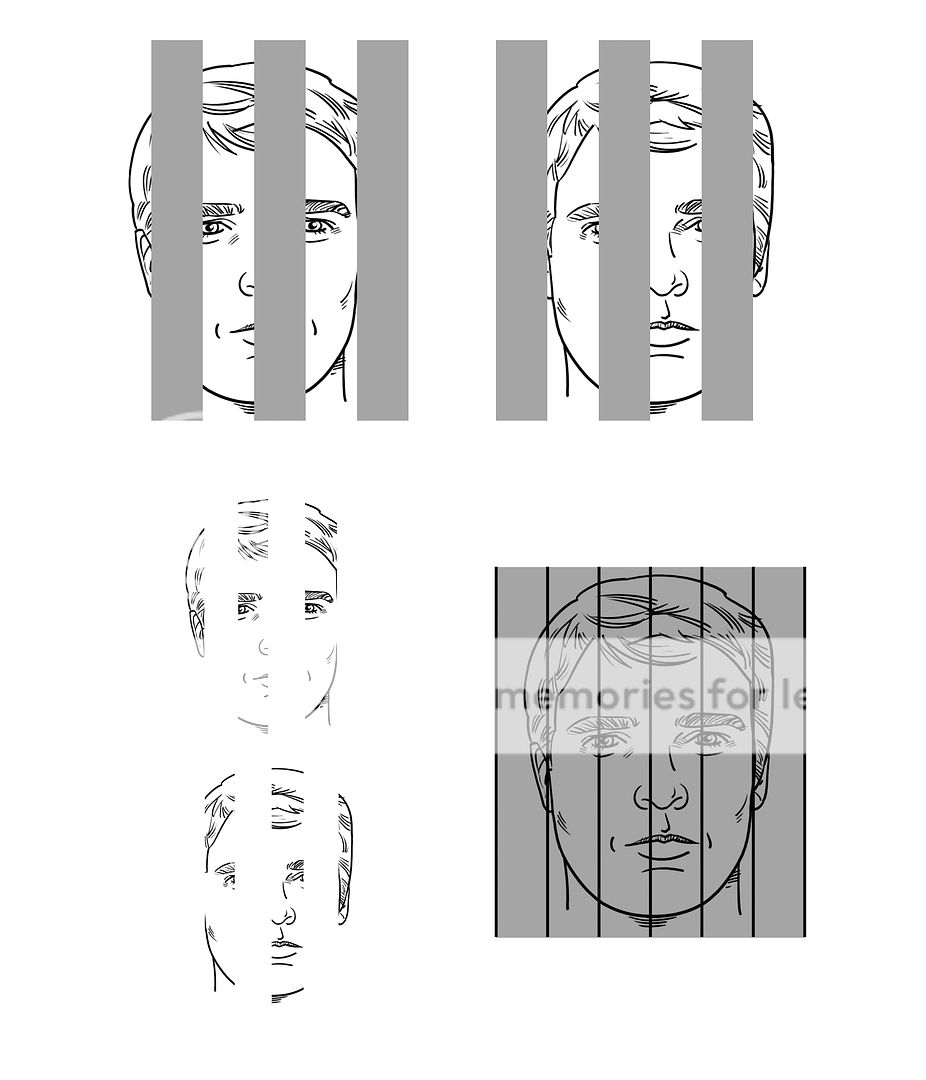

Dr. Mark Changizi, a cognitive science researcher, and professor at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, is one of the most exciting rising stars of science writing and the neurobiology of popular culture phenomena. His latest book, The Vision Revolution, expounds on the evolution and nuances of the human eye—a meticulously designed, highly precise technological marvel that allows us to have superhuman powers. You heard me right; superhuman! X-ray vision, color telepathy, spirit reading, and even seeing into the future. Dr. Changizi spoke about these ideas, and how they might be applied to everything from sports stars with great hand-eye coordination to modern reading and typeface design with us in ScriptPhD.com’s inaugural audio podcast. He also provides an exclusive teaser for his next book with a guest post on the surprising mindset that makes for creative people. Read Dr. Changizi’s guest post and listen to the podcast under the “continue reading” cut.

You are an idea-monger. Science, art, technology—it doesn’t matter which. What matters is that you’re all about the idea. You live for it. You’re the one who wakes your spouse at 3am to describe your new inspiration. You’re the person who suddenly veers the car to the shoulder to scribble some thoughts on the back of an unpaid parking ticket. You’re the one who, during your wedding speech, interrupts yourself to say, “Hey, I just thought of something neat.” You’re not merely interested in science, art or technology, you want to be part of the story of these broad communities. You don’t just want to read the book, you want to be in the book—not for the sake of celebrity,

but for the sake of getting your idea out there. You enjoy these creative disciplines in the way pigs enjoy mud: so up close and personal that you are dripping with it, having become part of the mud itself.

Enthusiasm for ideas is what makes an idea-monger, but enthusiasm is not enough for success. What is the secret behind people who are proficient idea-mongers? What is behind the people who have a knack for putting forward ideas that become part of the story of science, art and technology? Here’s the answer many will give: genius. There are a select few who are born with a gift for generating brilliant ideas beyond the ken of the rest of us. The idea-monger might well check to see that he or she has the “genius” gene, and if not, set off to go monger something else.

Luckily, there’s more to having a successful creative life than hoping for the right DNA. In fact, DNA has nothing to do with it. “Genius” is a fiction. It is a throw-back to antiquity, where scientists of the day had the bad habit of “explaining” some phenomenon by labeling it as having some special essence. The idea of “the genius” is imbued with a special, almost magical quality. Great ideas just pop into the heads of geniuses in sudden eureka moments; geniuses make leaps that are unfathomable to us, and sometimes even to them; geniuses are qualitatively different; geniuses are special. While most people labeled as a genius are probably somewhat smart, most smart people don’t get labeled as geniuses.

I believe that it is because there are no geniuses, not, at least, in the qualitatively-special sense. Instead, what makes some people better at idea-mongering is their style, their philosophy, their manner of hunting ideas. Whereas good hunters of big game are simply called good hunters, good hunters of big ideas are called geniuses, but they only deserve the moniker “good idea-hunter.” If genius is not a prerequisite for good idea-hunting, then perhaps we can take courses in idea-hunting. And there would appear to be lots of skilled idea-hunters from whom we may learn.

There are, however, fewer skilled idea-hunters than there might at first seem. One must distinguish between the successful hunter, and the proficient hunter – between the one-time fisherman who accidentally bags a 200 lb fish, and the experienced fisherman who regularly comes home with a big one (even if not 200 lbs). Communities can be creative even when no individual member is a skilled idea-hunter. This is because communities are dynamic evolving environments, and with enough individuals, there will always be people who do generate fantastically successful ideas. There will always be successful idea-hunters within creative communities, even if these individuals are not skilled idea-hunters, i.e., even if they are unlikely to ever achieve the same caliber of idea again. One wants to learn to fish from the fisherman who repeatedly comes home with a big one; these multiple successful hunts are evidence that the fisherman is a skilled fish-hunter, not just a lucky tourist with a record catch.

And what is the key behind proficient idea-hunters? In a word: aloofness. Being aloof—from people, from money, from tools, and from oneself—endows one’s brain with amplified creativity. Being aloof turns an obsessive, conservative, social, scheming status-seeking brain into a bubbly, dynamic brain that resembles in many respects a creative community of individuals. Being a successful idea-hunter requires understanding the field (whether science, art or technology), but acquiring the skill of idea-hunting itself requires taking active measures to “break out” from the ape brains evolution gave us, by being aloof.

I’ll have more to say about this concept over the next year, as I have begun writing my fourth book, tentatively titled Aloof: How Not Giving a Damn Maximizes Your Creativity. (See here and here for other pieces of mine on this general topic.) In the meantime, given the wealth of creative ScriptPhD.com readers and contributors, I would be grateful for your ideas in the comment section about what makes a skilled idea-hunter. If a student asked you how to be creative, how would you respond?

Mark Changizi is an Assistant Professor of Cognitive Science at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in New York and the author of The Vision Revolution and The Brain From 25,000 Feet. More of Dr. Changizi’s writing can be found on his blog, Facebook Fan Page, and Twitter.

ScriptPhD.com was privileged to sit down with Dr. Changizi for a half-hour interview about the concepts behind his current book, The Vision Revolution, out in paperback June 10, the magic that is human ocular perception, and their applications in our modern world. Listen to the podcast below:

X-Ray Eyes: In the face of clutter (i.e. a fence), our left and right eyes take partial images (top two figures), transpose them (bottom left figure) to construct a complete image (bottom right figure).

~*ScriptPhD*~

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology

in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development.

Follow us on Twitter and our Facebook fan page. Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

]]>

You spot someone across a crowded room. There is eye contact. Your heart beats a little faster, palms are sweaty, you’re light-headed, and your suddenly-squeamish stomach has dropped to your knees. You’re either suffering from an onset of food poisoning or you’re in love. But what does that mean, scientifically, to fall in love, to be in love, to stay in love? In our special Valentine’s Day post, Editor Jovana Grbić expounds on the neuronal and biophysical markers of love, how psychologists and mathematicians have harnessed (and sometimes manipulated) this information to foster 21st Century digital-style romance, and concludes with a personal reflection on what love really means in the face of all of this science. You might just be surprised. So, Cupid, draw back your sword… and click “continue reading” for more!

What is This Thing Called Love?

Scientists are naturally attracted to romance. Why do we love? Falling in love can be many things emotionally, ranging from the exhilarating to the truly frightening. It is, however, also remarkably methodical, with three stages developed by legendary biological anthropologist Helen Fisher of Rutgers University—lust, attraction and attachment—each with its own distinct neurochemistry. During lust, in both men and women, two basic sex hormones, testosterone and estrogen, primarily drive behavior and psychology. Interestingly enough, although lust has been memorialized by artists aplenty, this stage of love is remarkably analytical. Psychologists have shown that those individuals primed with thoughts of lust had the highest levels of analytical thinking, while those primed with thoughts of love had the highest levels of creativity and insight. But we’ll get to love in a minute.

Chocolate may be a great gift of love for very biological reasons.

During attraction, a crucial trio of neurotransmitters, adrenaline, dopamine and serotonin, literally change our brain chemistry, leading to the phase of being obsessed and love-struck. Remember how we talked about a racing heart and sweaty palms upon seeing someone you’re smitten with? That would be a rush of adrenaline (also referred to as epinephrine), the “fight or flight” hormone/neurotransmitter, responsible for increased heart rate, contraction of blood vessels, and dilation of air passages. Dopamine is an evolutionarily-conserved, ubiquitous neurotransmitter the regulates basic functions such as anatomy, movement and cognition—a reason the loss of dopamine in Parkinson’s Disease patients can be so devastating. Dopamine is also responsible for the pleasure and reward mechanisms in the brain, hyperactivated by abuse of drugs such as cocaine and heroin. It has even been linked to creativity and idea generation via interactions of the frontal and temporal lobes and the limbic system. This is, therefore, that link between love and creativity that we mentioned above. Incidentally, the releasing or induction agent of norepinephrine and dopamine is a chemical called phenethylamine (PEA). Did you give your sweetheart chocolates for Valentine’s Day? If so, you did well, because chocolate is loaded with some of the highest naturally-occurring levels of phenethylamine, leading to a “chocolate theory of love.” If you can’t stop thinking about your beloved, it’s because of serotonin, one of love’s most important chemicals. Its neuronal functions include regulation of mood, appetite, sleep, and cognitive functions—all affected by love. Most modern generation antidepressants involve alteration of serotonin levels in the brain.

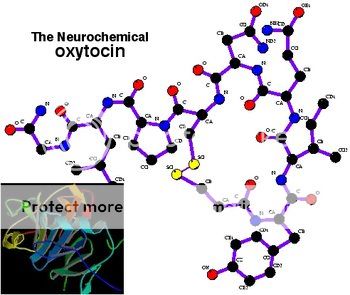

The neurochemical oxytocin's chemical and protein structure.

During latent attachment, two important chemicals “seal the deal” for long-term commitment: oxytocin and vasopressin. Oxytocin, often referred to as “the hormone of love,” is a neurotransmitter released during childbirth, breastfeeding and orgasms, and is crucial for species bonding, trust, and unconditional love. A sequence of experiments showed that trust formation in group activities, social interaction, and even psychological betrayal hinged on oxytocin levels. Vasopressin is a hormone responsible for memory formation and aggressive behavior. Recent research also suggests a role for vasopressin in sexual activity and in pair-bond formation. When vasopressin receptor gene was transplanted into mice (natural loners), they exhibited gregarious, social behaviors. That gene, the vasopressin receptor, was isolated in the prarie vole, among the select few of habitually monogamous mammals. When the receptor was introduced into their highly promiscuous Don Juan meadow vole relatives, they reformed their wicked rodent ways, fixated on one partner, guarded her jealously, and helped rear their young.

With all these chemicals floating around in the brain of the aroused and the amorous, it’s not surprising that scientists have deduced that the same brain chemistry responsible for addiction is also responsible for love!

The aforementioned Dr. Fisher gave an exceptional TED Talk in 2006 about her research in romantic love; its evolution, its biochemistry, and its social importance:

An fMRI brain scan of a person in love shows specific areas that are "lit up" or activated, notably the cerebellum (lower left-hand corner), the thalamus (middle dot) and the cingulate girus of the limbic cortex (right).

While the heart may hold the key to love, the brain helps unlock it. In fact, modern neuroscience and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scanning has helped answer a lot of questions about lasting romances, what being in love looks like, and whether there is a neurological difference between how we feel about casual sex, platonic friends, and those we’re in love with. In a critical fMRI study the brains of people who were newly in love were scanned while they looked at photographs, some of their friends and some of their lovers. Pictures of lovers activated specific areas of the brain (pictured on the left) that were not active when looking at pictures of good friends or thinking about sexual arousal, suggesting that romantic love and mate attachment aren’t so much of an emotion or state of mind as they are a deeply rooted drive akin to hunger, thirst and sex. Furthermore, a 2009 Florida State study showed that people in a committed relationship and are thinking of their partner subconsciously avert their eyes from an attractive member of the opposite sex. The most heartwarming part of all? It lasts. fMRI imaging of 10 women and 7 men still claiming to be madly in love with their partners after an average of 21 years of marriage showed equal brain activation to the earlier studies of nascent romances.

In case you’re blinded by all this science, remember this central fact about love: it’s good for you! The art of kissing has been shown to promote many health benefits, including stress relief, prevention of tooth and gum decay, a muscle workout, anti-aging effects, and therapeutic healing. If everything goes well with the kissing, it could lead to an even more healthy activity… sex! Not only does sex improve your sense of smell, boost fitness and weight loss, mitigate depression and pain, but it also strengthens the immune system, prevents heart disease and prostate cancer. In fact, “I have a headache” may be a specious excuse to avoid a little lovin’ since sex has been shown to cure migraines (and cause them, so be careful!). All of these facts and more, along with everything you ever wanted to know about sex, were collected and studied by neuroscientist Barry Komisaruk, endocrinologist Carlos Beyer-Flores and sexuality researcher Beverly Whipple in The Science of Orgasm. Add it to your shopping list today! The above activities may find you marching down the aisle, which especially for men is a very, very good thing. Studies show that married men not only live longer and healthier lives but also made more money and were more successful professionally (terrific New York Times article here).

Love in the Age of Algebra

While science can pinpoint the biological markers of love, can it act as a prognosticator of who will get together, and more importantly, stay together? Mathematicians and statisticians are sure trying! One of the foremost world-renowned experts on relationship and marriage modeling is University of Washington psychology professor John Gottman, head of The Gottman Institute and author of Why Marriages Succeed or Fail. Dr. Gottman uses complex mathematical modeling and microexpression analysis to predict with 90% accuracy which newlyweds will remain married four to six years later, and with 83% accuracy seven to nine years thereafter. In this terrific profile of Gottman’s “love lab,” we see that his methodology includes use of a facial action coding system (FACS) to analyze videotapes for minute signs of negative expressions such as contempt or disgust during simple conversations or stories. Take a look at this brief, fascinating video of how it all works:

Naturally, the next evolutionary step has been to cash in on this science in the online dating game, where successful matchmaking hinges on predicting which couples will be ideally suited to each other on paper. Dr. Helen Fisher has used her expertise in the chemicals of love to match couples through their brain chemistry personality profiles on Chemistry.com. eHarmony has an in-house research psychologist, Gian Gonzaga, an ardent proponent of personality assessment and skeptic of opposites attracting. Finally, the increasingly popular Match.com boasts of a radically advanced new personality profile called “match insights,” devised by none other than Dr. Fisher and medical doctor Jason Stockwood. If you don’t believe in the power of the soft sciences, you can take your matchmaking to a molecular level, with several new companies claiming to connect couples based on DNA fingerprints and the biological instinct to breed with people whose immune system differs significantly from ours for genetic stability. ScientificMatch.com promises that its pricey, patent-pending technology “uses your DNA to find others with a natural odor you’ll love, with whom you’d have healthier children, a more satisfying sex life and more,” while GenePartner.com tests couples based on only one group of genes: human leukocyte antigens (HLAs), which play an essential role in immune function. The accuracy of all of these sites? Mixed. Despite the problem of rampant lying in internet dating profiles and dating in volume to pinpoint the right match, some research has shown remarkably high success (as high as 94%) in e-partners that had met in person.

What’s Science Got To Do With It?

In the shadow of such vast technological advancement and deduction of romance to the binary and biological, readers of this blog might imagine that its scientist editor might condemn decidedly empirical views of love. They would be wrong. For while numbers and test tubes and brain scanning machines can help us describe love’s physiological and psychological nimbus, its esoteric nucleus will forever be elusive. And thank heavens for that! There exists no mathematical formula (other than perhaps chaos theory) that can explain the idea of two people, diametrical as day and night, falling in love and somehow making it work. No MRI is equipped with a magnet strong enough to properly quantify the utter heartbreak of those that don’t. There is not a statistical deviation alive that could categorize my grandparents’ unlikely 55-year marriage, a marriage that survived World War II, Communism, a miscarriage, the death of a child, poverty, imprisonment in a political gulag, and yes, even a torrid affair. After my grandfather died, my grandmother eked out another feeble few years before succumbing to what else but a broken heart. It is within that enigma that generations of poets, scribes, musicians, screenwriters, and artists dating all the way back to humanity’s cultural dawning—the Stone Age—have never exhausted of material, and they never will.

Love exists outside of all the things that science is—the ordered, the examined, the sterile, the safe, and the rational. It is inherently irrational, messy, disordered and frustrating. Science and technology forever aim to eliminate mistakes, imperfection and any obstacles to precision, which in matters of the heart would be a downright shame. Love is not about impersonal personality surveys, neurotransmitter cascades or the incessant beeping of laboratory machines measuring its output. It’s about magic, mystery, voodoo and charm. It’s about experimenting, floating off the ground, being scared out of your mind, laughing uncontrollably and inexplicably, flowers, bad dates, good dates, tubs of ice cream and chocolate with your closest friends, picking yourself up and starting the whole process all over again. It’s not about guarantees or prognostications, not even by smart University of Washington psychologists. It’s about having no clue what you’re doing, figuring it out as you go along, deviating from formulas, books, and everything scientists have ever told you, taking a chance on the stranger across a crowded room, and the moon hitting your eye like a big-a pizza pie.

Now that’s amore!

Hope everyone had a great Valentine’s Day.

~*ScriptPhD*~

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development.

Follow us on Twitter and our Facebook fan page. Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

]]>

“First of all, let me assert my firm belief that the only thing we have to fear is fear itself—nameless, unreasoning, unjustified terror which paralyzes needed efforts to convert retreat into advance.” These inspiring words, borrowed from scribes Henry David Thoreau and Michel de Montaigne, were spoken by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt at his first inauguration during the only era more perilous than the one we currently face. But FDR had it easy. All he had to face was 25% unemployment and 2 million homeless Americans. We have, among other things, climate change, carcinogens, leaky breast implants, the obesity epidemic, the West Nile virus, SARS, avian/swine flu, flesh-eating disease, pedophiles, predators, herpes, satanic cults, mad cow disease, crack cocaine, and let’s not forget that paragon of Malthusian-like fatalism—terror. In his brilliant book The Science of Fear, journalist Daniel Gardner delves into the psychology and physiology of fear and the incendiary factors that drive it, including media, advertising, government, business and our own evolutionary mold. For our final blog post of 2009, ScriptPhD.com extends the science into a personal reflection, a discussion of why, despite there never having been a better time to be alive, we are more afraid than ever, and how we can turn a more rational leaf in the year 2010.

The brain of our tree-swinging ancestors first ballooned from 400 to 600 cubic centimeters 2-2.5 million years ago. 500,000 years ago, the ancestral human brain expanded to 1,200 cubic centimeters. Modern human brains are 1,400 cubic centimeters.

Prehistoric Predispositions and the Human Brain

Let’s talk about psychology for a moment. The psychology of fear, to be specific. Our minds largely evolved to cope with the “Environment of Evolutionary Adaptation”; Stone Age survival needs hard-wired into our brains to create a two-tiered system of conscious and subconscious thought. Elucidated by 2002 Nobel Prize winner in economics Daniel Kahneman, the systems are divided into the prehistoric System One (Gut) and System Two (Head). Gut is quick, evolutionary and designed to react to mortal threats, while Head is more modern, conscious thought capable of analyzing statistics and being rational. In a seminal 1974 paper published in the journal Science, Kahneman and his research partner Amos Tversky punctured the long-held belief that decision-making occurs via a Homo economicus (rational man) by proving that decisions are mostly made by the gut using three simple heuristics, or rules. The anchoring and adjustment heuristic (Anchoring Rule) involves grabbing hold of the nearest or most recent number when uncertain about a correct answer. This helps explain why the number 50,000 has been used to describe everything from how many predators are on the Internet in the 2000s to how many children were kidnapped by strangers every day in the 80s to the number of murders committed by Satanic cults in the 90s. The representativeness heuristic, or Rule of Typical Things, is our Gut judging things based on largely learned intuition. This explains why many predictions by experts are often as wrong as they are right. And why, despite being convinced they are not racist, Western societies perpetuate a dangerous stereotype of the non-white male. Finally, and most importantly, the availability heuristic, or Example rule, dictates that the easier it is to recall examples of something, the more common it must be. This is particularly sensitive to our memory formation and retention, particularly of violent or painful events, which were key to species survival in dangerous prehistoric times.

University of Oregon psychologist Paul Slovic added to these the affect heuristic, or Good/Bad Rule. When faced with something unfamiliar, Gut instantly decides how likely it is to kill it based on whether it feels good or should be good. This explains why we irrationally fear nuclear power, which have intellectually been shown to not be nearly as dangerous as we think they are, while we have no qualms about suntanning on a beach, which feels good, or getting an X-ray at the doctor’s office despite both having been shown to be more dangerous than estimated. Psychologists Marty Frank and Thomas Gilovich showed that in all but one season from 1970 to 1986, the five teams in the NFL and three teams in the NHL that wore black uniforms (black = bad) got more penalty yards and penalty minutes than league-average, respectively, even when wearing their alternate uniforms. Finally, scientist Peter Watson discovered that people judge risk not based on scientific information, but rather herd mentality and conformity, termed confirmation bias. Once having formed a view, we cling to information that supports that view while rejecting or ignoring information that casts any doubt on it. This can be seen in internet blogs of like-minded individuals that act as echo chambers and media and organization perpetuating a fear as rumor until it is accepted by the group as a mortal danger, despite no rational evidence to the contrary.

It’s a downright shame that this hallowed body of research took scientists such a long time to amass and ascertain, because they could have easily found it in the skyscrapers of Madison Avenue, where the psychology of fear has not only been long-defined, but long-exploited by advertising agencies and media moguls to sell products, news, and…more fear.

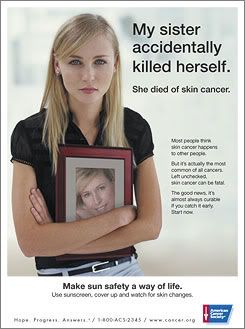

Copy: "My sister accidentally killed herself. She died of skin cancer. Most people think skin cancer happens to other people. But it's actually the most common of all cancers. Left unchecked, skin cancer can be fatal. The good news, it's almost always curable if you catch it early. Start now. Make sun safety a way of life. Use sunscreen, cover up and watch for skin changes."

At its heart, effective advertising has always been about forming an emotional bond with consumers on an individual level. People are more likely to engage with a brand or buy a product if they can feel a deep connection or personal stake. This can be achieved through targeted storytelling, creativity, and the tapping and marketing of subconscious fear, coined as “schockvertising” by ad agencies. “X is a frightening threat to your safety or health, but use our product to make it go away.” It’s a surprisingly effective strategy and has been applied of late to disease (terrific read on pharmaceutical advertising tactics), the organic/natural movement, and politics. Purell (which The ScriptPhD will disclose being a huge fan of) was originally created by Pfizer for in-hospital use by medical professionals. In 1997, it was introduced to market with an ad blitz that included the slogan “Imagine a Touchable World.” I just did; it’s called the world up until 1997. Erectile dysfunction, hair loss, osteoporosis, restless leg syndrome, shyness, and even toenail fungus are now serious ailments that you need to ask your doctor about today. This camouflaged marketing extends to health lobby groups, professional associations, and even awareness campaigns. Roundly excoriated by medical professionals, a 2007 ad campaign pictured on the right warned of the looming dangers of skin cancer. Though the logo on the poster is that of the American Cancer Society, it’s sponsored by Neutrogena—a leading manufacturer of sunscreen.

“For the first time in the history of the world, every human being is now subjected to contact with dangerous chemicals, from the moment of conception until death,” wrote marine biologist Rachel Carson in her 1962 environmental bombshell Silent Spring. Up until then, ‘chemical’ was not a dirty word. In fact it was associated with progress, modernity, and prosperity, as evidenced by DuPont Corporation’s 1935 slogan “Better things for better living…through chemistry” (the latter part being dropped in 1982). Carson’s book preyed on what has become the biggest fear in the last half-century: cancer. It famously predicted that one in every four people would be stricken with the disease over the course of their lifetimes. These fears have been capitalized on by the health, nutrition and wellness industry to peddle organic, natural foods and supplements that veer far away from laboratories and manufactured synthesis. While there is nothing wrong with digging into a delicious meal of organic produce or popping a ginseng pill, the naturally occurring chemicals in the food supply exceed one million, none of which are liable to the rigorous safety guidelines and regulations that are performed on perscription drugs, pesticides and non-organic foods. In fact, the lifetime cancer risk figures invoked by everyone from Greenpeace to Whole Foods is not nearly as scary when adjusted for age and lifestyle. “Exposure to pollutants in occupational, community, and other settings is thought to account for a relatively small percentage of cancer deaths,” according to the American Cancer Society in Cancer Facts and Figures 2006. It’s lifestyle—smoking, drinking, diet, obesity and exercise—that accounts for 65% of all cancers, but it’s not nearly as sexy to stop smoking as it is to buy that imported Nepalese pear hand-picked by a Himalayan sherpa. Of course, this hasn’t prevented the organic market from growing 20% each year since the early 90s, with a 20-year marketing plan. The last frontier of fear advertising is politics. Anyone who has seen a grainy, black and white negative ad may be cognizant they are being manipulated, but may not know exactly how. Coined the “get ‘em sick, get ‘em well” model in the 1980s, political scientist Ted Brader notes in Campaigning for Hearts and Minds that 72 percent of such ads dominate an appeal to emotions versus logic, with nearly half appealing to anger, fear or pride. Take a look at the gem that started them all, a controversial, game-changing 1964 commercial called “Daisy Girl”. Emotional, visceral, and only aired once, this ad was widely credited with helping Lyndon B. Johnson defeat Barry Goldwater in the Presidential election: