Helix poster and stills ©2014 NBC Universal, all rights reserved.

The biggest threat to mankind may not end up being an enormous weapon; in fact, it might be too small to visualize without a microscope. Between global interconnectedness and instant travel, the age of genomic manipulation, and ever-emerging infectious disease possibilities, our biggest fears should be rooted in global health and bioterrorism. We got a recent taste of this with Stephen Soderberg’s academic, sterile 2011 film Contagion. Helix, a brilliant new sci-fi thriller from Battlestar Galactica creator Ronald D. Moore, isn’t overly concerned with whether the audience knows the difference between antivirals and a retrovirus or heavy-handed attempts at replicating laboratory experiments and epidemiology lectures. What it does do is explore infectious disease outbreak and bioterrorism in the greater context of global health and medicine in a visceral, visually chilling way. In the world of Helix, it’s not a matter of if, just when… and what we do about it after the fact. ScriptPhD.com reviews the first three episodes under the “continue reading” cut.

The benign opening scenes of Helix take place virtually every day at the Centers for Disease Control, along with global health centers all over the world. Dr. Alan Farragut, leader of a CDC outbreak team, is assembling and training a group of researchers to investigate a possible viral outbreak at a remote research called Arctic Biosystems. Tucked away in Antarctica under extreme working conditions, and completely removed from international oversight, the self-contained building employs 106 scientists from 35 countries. One of these scientists, Dr. Peter Farragut, is not only Alan’s brother but also appears to be Patient Zero.

CDC researcher Dr. Sarah Jordan uncovers a victim of the Narvic A virus in a scene from “Helix.”

It doesn’t take the newly assembled team long to discover that all is not as it seems at Arctic Biosystems. Deceipt and evasiveness from the staff lead to the discovery of a frightening web of animal research, uncovering the tip of an iceberg of ‘pseudoscience’ experimentation that may have led to the viral outbreak, among other dangers. The mysterious Dr. Hiroshi Hatake, the head of Ilaria Corporation, which runs the facility, may have nefarious motivations, yet is desperately reliant on the CDC researchers to contain the situation. The involvement of the US Army engineers and scientists, culminating in a shocking, devastating ending to the third episode, hints that the CDC doesn’t think the outbreak was accidental. Most frightening of all is the discovery of two separate strains of the virus, Narvic A and Narvic B, the former of which turns victims into a bag of Ebola-like hemorrhagic black sludge, while the latter rewires the brain to create superhuman strength – a perfect contagion machine.

With some pretty brilliant sci-fi minds orchestrating the series, including Moore, Lost alum Steven Maeda and Contact producer Lynda Obst, it’s not surprising that Helix extrapolates extremely accurate and salient themes facing today’s scientific environment. Spot on is the friction between communication and collaboration between the agencies depicted on the show – the CDC, bioengineers from the US Army and the fictional Arctic Biosystems research facility. In reality, identifying and curtailing emerging infectious disease outbreaks requires a network of collaboration among, chiefly, the World Health Organization, the CDC, the US Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases (USAMRIID, famously portrayed in the film Outbreak) and local medical, research and epidemiological outposts at the outbreak site(s). In addition to managing egos, agencies must quickly share proprietary data and balance global oversight (WHO) with local and federal juristictions, which can be a challenge even under ordinary conditions. To that extent, including a revised set of international health regulations in 2005 and the establishment of an official highly transimissible form of the virus created a hailstorm of controversy. In addition to a publishing moratorium of 60 days and censorship of key data, debate raged on the necessity of publishing the findings at all from a national security standpoint and the benefit to risk value of such “dual-use” research. Similar fears of “playing God” were stoked after the creation of a fully synthetic cell by J. Craig Venter and the team behind the Genome Project.

Arctic Biosystems head Dr. Hiroshi Hatake and his security head Daniel Aerov watch over CDC Dr. Alan Farragut, sealed off in a Biosafety Level 4 laboratory in a scene from “Helix.”

As with Moore’s other SyFy series, Battlestar Galactica, Helix is not perfect, and will need time and patience (from both the network and viewing audience) to strike the right chemistry and develop evenness in its storytelling. The dialogue feels forced at times, particularly among the lead characters and with rapid fire high-level scientific jargon, of which there is a surprising amount. Certain scenes involving the gruesomeness of the viruses feel too long and repetitive in the first episodes, but this will quickly dissipate as the plot develops. But for all of its minor blemishes, Helix is one of the smartest scientific premises to hit television in recent times, and looks to deftly explore familiar sci-fi themes of bioengineering ethics and the risks of ‘playing God’ just because we have the technology to do so.

We’ve become accustomed to sci-fi terrifying us visually, such as the ‘walker’ zombies of The Walking Dead or even psychologically, as in the recent hit movie Gravity. But Helix’s terror is drawn from the utter plausibility of the scenario it presents.

View an extended 15 minute sample of the Helix pilot here:

Helix will air on Friday nights at 10:00 PM ET/PT on SyFy channel.

~*ScriptPhD*~

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire us for creative content development.

Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

]]>

Defiance television show and video game images are ©2013 NBC Universal. All rights reserved.

SyFy channel’s new show Defiance is breaking the mold in every way. An unusual combination of fantasy blockbuster, small town mystery and sci-fi action drama, Defiance takes place on a decimated, post-apocalyptic Earth set several decades into the future. After an alien invasion and war, hmans try to co-exist with a group of aliens that are both friend and foe in a small town literally defying the odds. ScriptPhD.com was extremely fortunate to have access to one of the head writers of the show, as well as its official science advisor. In our interviews, we delve deeper into the backbone of this sci-fi hit, which is a terrific, engaging story, paired with colorful characters and the clever incorporation of science to support the plot. More after the “continue reading” cut.

Defiance is set amidst a backdrop of the ruins of a major American city, formerly St. Louis, now called Defiance, where a group of humans and aliens must survive under extreme political and existential circumstances. Jeb Nolan, a former military hero who fought the last battle of the human-Votan war, aptly named the Battle of Defiance, is now a wanderer looking for his place in the world. His adopted daughter Irisa, from a Votan alien tribe called the Castathans, is also battling a difficult past as she migrates between the world of her own people as friends and foes. In the middle of episodic mysteries, such as who is behind an attack on Defiance, or the murder mystery of the town mining magnate’s son, is a larger storyline about the integration of human and alien races in a unique post-apocalyptic melting pot.

For the SyFy channel, Defiance looks like the first bona fide hit since Battlestar Galactica, whose prequel follow-up Caprica never managed to latch on with a consistent audience. It’s premiere had the highest ratings since Eureka and follow up episodes are holding a steady audience.

And if its intricate plot isn’t enough to keep viewers hooked, Defiance is defying traditional media by merging the show with a concomitant multiplayer online video game concept, where action takes place simultaneously in San Francisco. The events that take place in the video game, which has already recorded one million registered users, will impact the storyline of the show to varying degrees, and vice versa. It is without a doubt the most interactive and ambitious storytelling format ever attempted for the genre from a technical standpoint.

ScriptPhD.com was very honored to have the opportunity to sit down with both series writer and co-creator and executive producer Michael Taylor, as well as the show’s scientific advisor Kevin Grazier, to get a better idea of the characters, storyline and what we can expect going forward.

A couple of the Votan races represented on Defiance: the Indigenes (the town doctor on the left) and Castathans (Irisa, one of the principal characters).

Taylor, also a series writer and producer on breakout SyFy hit series Battlestar Galactica, was involved in the early development of the series, which took over one and a half years to re-conceptualize and bring to the small screen from its initial concept. “Keep in mind, the original draft [of the pilot] was very different,” Taylor says. “The Chief Lawkeeper role was prototyped as this older, wry Brian Dennehy-type of character, for example. Irathient warrior Irisa was more of a wide-eyed, naïve girl than she is in the current version. We even had about two to three episodes of the series done. But as we went along, we were finding it hard to keep thinking up episodes from week to week.” Which is when the series went back to the drawing boards.

And reimagine the series they did! Unlike the vast majority of sci-fi shows, which explore the process of warring factions integrating and co-existing, in Defiance, this has already occurred, something that Taylor calls a “cool experiment.” “The 30-year-war has already been fought, all that stuff is long in the past,” Taylor reminds us. “And now we are at the point where the 8 races are trying to co-exist together. Remember, in the opening episode, the mayor [Amanda Rosewater] tells the multi-ethnic crowd that Defiance is a pretty nice place to live.” Which is in stark contrast to the vast majority of the now-destroyed Earth, which remains a very dangerous, primitive environment, as is seen in the opening minutes of the pilot. But the relatively peaceful, self-contained environment of Defiance is not the only way it differs. “This idea of the 8 races living together is still pretty rare [throughout Earth],” Taylor remarks. “In fact, in Rio de Janeiro you have the opposite with the Votan-led Earth Republic, which has pretty much the

opposite goal than what’s happening in Defiance.”

People should also be careful about inferring too many sociological or current events extrapolations from the themes explored in the show. For Taylor, the writers and creators are mainly exploring a fun concept with strong storytelling and even stronger characters. And what characters they are!

Lawkeeper Jeb Nolan and his adopted daughter Irisa are both dark, complex characters with extremely difficult pasts. “In many ways, they complement each other and need each other,” Taylor says. “They are the only two people who can complete one another because of that bond.” But they aren’t the only characters with a past. New young mayor Amanda herself has some dark secrets that fuel her motivations, many of which will be explored in future episodes, according to Taylor. At the mere suggestion that mysterious ex-mayor Nicky, who figures into the Votan plot against the humans, might not be that evil, Taylor retorts: “Nope, she’s evil. She just rationalizes her actions as the end justifying the means.”

As for integrating the video game concept, it predated the show by five years, which allowed writers to establish stories and character development that will happen separately from, albeit concurrently with, the action in Defiance onscreen. It also affords the writers on the show some freedom with the knowledge that the events in the video game don’t necessarily impact the flow of the storyline right away. “With the production schedule of television, there’s no way that we would be able to incorporate plots from the video game into the show that quickly,” says Taylor. “But remember, there is a summer hiatus between seasons, so you never know. Maybe that would be a time the writers would be able to look at some of the events that gamers chose and fold them into the story with more leisure.”

So rest assured, those of you enjoying Defiance, whether on your televisions or XBoxes. Plenty of sci-fi action is yet to come.

A scene from the Defiance interactive video game.

In case viewers are worried that Defiance’s deep focus on character development and storyline layout (in two media formats no less!) is going to come at the expense of accurate and interesting science, fear not. The production staff at the sci-fi hit has employed the services of notable scientific advisor Kevin Grazier, who also advised on Eureka and Battlestar Galactica, along with a slew of feature films.

“We’ve seen time and time again small plot points that have become little tidbits, or plot points or even major points driving an episode when you get the science right,” Grazier notes. “Caring about the science [in a series plot] can be as much of a strength as it is a constraint.”

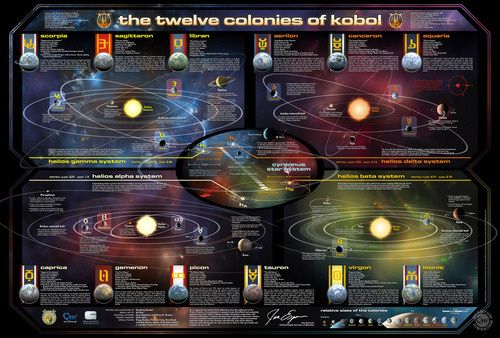

And while it’s true that the science of Defiance does seem a bit less obvious or upfront than in shows like BSG or Eureka, it’s no less important nor is it any less incorporated. “We have a really rich, really well thought-out backstory, and that is very much informed by the science,” Grazier says. “We know that the V-7 [Votan] races came from the Votan System. What happened to their system? Well, we have that [mapped out], we know that.” He also pointed to subtle implications such as in the first few minutes of the pilot. When Irisa looks up at the sleeper pods, she says, “All those hundreds of years in space just to die in your sleep.” Grazier notes: “The subtle implication is that the V-7 aliens don’t go FTL [faster than light]. So we have figured out where they’re from and how far away they’re from and which direction of the sky they’re from and how long it took to get here.”

In addition to its elemental role in the backstory, science has also also had fun ‘little’ moments in the show, like the importance of the terrasphere in defending the Volge attack in the pilot or the hell bugs (a genetic amalgam of several earth critters) in episode 3. Some of these small scientific details were even able to result in cool visual effects. For example, when the table of writers was discussing the ark falls, Grazier, an astrophysicist by training, noted that the conservation of angular momentum meant that these things would not land vertically, but rather horizontally, using the screaming overhead comets in Deep Impact as a touchstone. Sure enough, in the first few minutes, you see Nolan and Irisa tracking what’s about to be an ark fall and you see them screaming overhead. “That will, by the way, come into play in a later episode,” Grazier teases. “We know where the ark belt is. Where the ships were when they blew up, how far away they are.”

For Grazier, the experience has not only been a rewarding one, but different from the other shows he’s worked on. “Just to give you an example of how great the Defiance writing team is with regards to the science, in an upcoming episode, the writers had written a script and there was a big incident in there that I said “You can’t do this scientifically.”" Grazier kept shooting down suggestion after suggestion, with series producer Kevin Murphy, who was a huge Basttlestar Galactica fan, staying patient and open to ideas despite being frustrated by the process. In the end, the series producers allowed Grazier to provide input to the plot that both worked scientifically and resulted in decent storytelling and visual effects. “There was a situation that the scientific content was a sticking point, and a fairly major element of the plot, and they let the science guy come up with the solution,” he remarked. “As satisfying as some of the other series that I’ve worked on have been, that’s never happened to me before.”

“Obviously in any sci-fi show, there are going to be a few [unrealistic] gimmes, a few conceits for the sake of the plot or entertainment,” Grazier reminds us. “But if you buy in that these terrashperes came down and transformed the Earth and take this journey with us, then the science will take you the rest of the way.”

Based on the first three episodes, it’s a journey I know is worth the ride.

Watch a feature-length trailer for the show here:

Watch a special video about the making of the Defiance

Defiance airs on Monday nights on SyFy Channel at 9 ET/PT.

~*ScriptPhD*~

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development.

Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

]]>

For every friendly robot we see in science fiction such as Star Wars’s C3PO, there are others with a more sinister reputation that you can find in films such as I, Robot. Most movie robots can indeed be classified into a range of archetypes and purposes. Science boffins at Cambridge University have taken the unusual step of evaluating the exact risks of humanity suffering from a Terminator-style meltdown at the Cambridge Project for Existential Risk.

“Robots On the Run” is currently an unlikely scenario, so don’t stockpile rations and weapons in panic just yet. But with machine intelligence continually evolving, developing and even crossing thresholds of creativity and and language, what holds now might not in the future. Robotic technology is making huge advances in great part thanks to the efforts of Japanese scientists and Robot Wars. For the time being, the term AI (artificial intelligence) might sound like a Hollywood invention (the term was translated by Steven Spielberg in a landmark film, after all), but the science behind it is real and is not going to go away. Robots can now actually learn things akin to the way humans pick up information. Nevertheless, some scientists believe that there are limits to the level of intelligence that robots will be able to achieve in the future. In a special ScriptPhD guest post, we examine the current state of artificial intelligence, and the possibilities that the future holds for this technology.

Is AI a false dawn?

While artificial intelligence has certainly delivered impressive advances in some respects, it has also not successfully implemented the kind of groundbreaking high-order human activity that some would have envisaged long ago. Replicating technology such as thought, conversation and reasoning in robots is extraordinarily complicated. Take, for example, teaching robots to talk. AI programming has enabled robots to hold rudimentary conversations together, but the conversation observed here is extremely simple and far from matching or surpassing even everyday human chit-chat. There have been other advances in AI, but these tend to be fairly singular in approach. In essence, it is possible to get AI machines to perform some of the tasks we humans can cope with, as witnessed by the robot “Watson” defeating humanity’s best and brightest at the quiz show Jeopardy!, but we are very far away from creating a complete robot that can manage our level of multi-tasking.

The android David exhibits wonder and surprise at a discovery in a scene from the 2012 sci-fi film “Prometheus.” Image and content ©2012 20th Century Fox, all rights reserved.

Despite these modest advances to date, technology throughout history has often evolved in a hyperbolic pattern after a long, linear period of discovery and research. For example, as the Cambridge scientists pointed out, many people doubted the possibility of heavier-than-air flight. This has been achieved and improved many times over, even to supersonic speeds, since the Wright Brothers’ unprecedented world’s first successful airplane flight. In last year’s sci-fi epic “Prometheus,” the android David is an engineered human designed to assist an exploratory ship’s crew in every way. David anticipates their desires, needs, yet also exhibits the ability to reason, share emotions and feel complex meta-awareness. Forward-reaching? Not possible now? Perhaps. But by 2050, computers controlling robot “brains” will be able to execute 100 trillion instructions per second, on par with human brain activity. How those robots order these trillions of thoughts, only time will tell!

If nature can engineer it, why can’t we?

A world dominated by artificial intelligence in a scene from Stephen Spielberg’s “A.I.” ©2001 Warner Brothers Pictures, all rights reserved.

The human brain is a marvelous feat of natural engineering. Making sense of this unique organ that makes humans who we are requires a conglomeration of neuroscience, mathematics and physiology. MIT neuroscientist Sebastian Seung is attempting to do precisely that – reverse engineer the human brain in order to map out every neuron and connection therein, creating a road map to how we think and function. The feat, called the connectome, is likely to be accomplished by 2020, and is probably the first tentative step towards creating a machine that is more powerful than human brain. No supercomputer that can simulate the human brain exists yet. But researchers at the IBM cognitive computing project, backed by a $5 million grant from US military research arm DARPA, aim to engineer software simulations that will complement hardware chips modeled after how the human brain works. The research is already being implemented by DARPA into brain implants that have better control of artificial prosthetic limbs.

The plausibility that technology will catch up to millions of years of evolution in a few years’ time seems inevitable. But the question remains… what then? In a brilliant recent New York Times editorial, University of Cambridge philosopher Huw Price muses about the nature of human existentialism in an age of the singularity. “Indeed, it’s not really clear who “we” would be, in those circumstances. Would we be humans surviving (or not) in an environment in which superior machine intelligences had taken the reins, to speak? Would we be human intelligences somehow extended by nonbiological means? Would we be in some sense entirely posthuman (though thinking of ourselves perhaps as descendants of humans)?” Amidst the fears of what engineered beings, robotic or otherwise, would do to us, lies an even scarier question, most recently explored in Vincenzo Natali’s sci-fi horror epic Splice: what responsibility do we hold for what we did to them?

Is it already checkmate AI?

Could large supercomputer capacity, pictured here at the IBM labs, eventually allow artificial intelligence to mimic human brain function?

Computers have already beaten humans hands down in a number of computational metrics, perhaps most notably when the IBM chess computer Deep Blue outwitted then-world champion Gary Kasparov back in 1997, or the more recent aforementioned quiz show trouncing by Watson. There are many reasons behind these supercomputing landmarks, not the least of which is the much quicker capacity for calculations and are not being subject to the vagaries of human error. Thus, from the narrow AI point of view, hyper-programmed robots are already well on their way, buoyed by hardware and computing advances and programming capacity. According to Moore’s law, the amount of computing power we can fit on a chip doubles every two years, an accurate estimation to date, despite skeptics who claim that the dynamics of Moore’s law will eventually have to end. Nevertheless, futurist Ray Kurtzweil predicts that computers’ role in our lives will expand far beyond tablets, phones and the Internet. Taking a page out of The Terminator, Kurtzweil believes that humans will eventually be implanted with computers (a sort of artificial intelligence chimera) for longer life and greater brain capacity. If the researchers developing artificial intelligence at Google X Labs have their say, this day will arrive sooner rather than later.

There may be no i in robot, but that does not necessarily mean that advanced artificial beings would be altruistic, or even remotely friendly to their organic human counterparts. They do not (yet) have the emotions, free will and values that humans use to guide our decision-making. While it is unlikely that robots would necessarily be outright hostile to humans, it is possible that they would be indifferent to us, or even worse, think that we are a danger to ourselves and the planet and seek to either restrict our freedom or do away with humans entirely. At the very least, development and use of this technology will yield considerable novel ethical and moral quandaries.

There may not be much telling what the future of technology holds just yet, but in the meantime, humanity can be comforted by the knowledge that it will be a while before an all-powerful robot crashes the party.

Reese Jones is a tech and gadget lover, a die-hard fan of iOS and console games. She writes about everything from quick tech tips, to mobile-specific news from the likes of O2, to tech-related DIY. Follow her on Twitter and Google+.

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development.

Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

]]>“The wars of the 21st Century will be fought over water.” —Ismail Serageldin, World Bank

Last Call at the Oasis film poster ©2012, Participant Media, all rights reserved.

Watching the devastation and havoc caused by Hurricane Sandy and several recent water-related natural disasters, it’s hard to imagine that global water shortages represent an environmental crisis on par with climate change. But if current water usage habits do not abate, or if major technological advances to help recycle clean water are not implemented, this is precisely the scenario we are facing—a majority of 21st Century conflicts being fought over water. From the producers of socially-conscious films An Inconvenient Truth and Food, Inc., Last Call at the Oasis is a timely documentary that chronicles current challenges in worldwide water supply, outlines the variables that contribute to chronic shortages and interviews leading environmental scientists and activists about the ramifications of chemical contamination in drinking water. More than just an environmental polemic, Last Call is a stirring call to action for engineering and technology solutions to a decidedly solvable problem. A ScriptPhD.com review under the “continue reading” cut.

A man in China hauls two buckets of water during a severe drought. Ongoing, frequent droughts represent a huge threat to China’s agricultural industry.

Although the Earth is composed of 70% water, only 0.7% (or 1% of the total supply) of it is fresh and potable, which presents a considerable resource challenge for a growing population expected to hit 9 billion people in 2050. In a profile series of some of the world’s most populous metropolises, Last Call vividly demonstrates that stark imagery of shortage crises is no longer confined to third world countries or women traveling miles with a precious gallon of water perched on their heads. The Aral Sea, a critical climate buffer for Russia and surrounding Central Asia neighbors, is one-half its original size and devoid of fish. The worst global droughts in a millennium have increased food prices 10% and raised a very real prospect of food riots. Urban water shortages, such as an epic 2008 shortage that forced Barcelona to import emergency water, will be far more common. The United States, by far the biggest consumer of water in the world, could also face the biggest impact. Lake Mead, the biggest supplier of water in America and a portal to the electricity-generating Hoover Dam, is only 40% full. Hoover Dam, which stops generating electricity when water levels are at 1050 feet, faces that daunting prospect in less than 4 years!

One strength of Last Call is that it is framed around a fairly uniform and well-substantiated hypothesis: water shortage is directly related to profligate, unsustainable water usage. Some usage, such as the 80% that is devoted to agriculture and food production, will merit evaluation for future conservation methods. California and Australia, two agricultural behemoths half a world apart, both face similar threats to their industries. But others, such as watering lawns. are unnecessary habits that can be reduced or eliminated. Toilets, most of which still flush 6 gallons in a single use, are the single biggest user of water in our homes—6 billion gallons per day! The US is also the largest consumer of bottled water in the world, with $11 billion in sales, even though bottled water, unlike municipal tap water, is under the jurisdiction of the FDA, not the EPA. As chronicled in the documentary Tapped, 45% of all bottled water starts off as tapped water, and has been subject to over 100 recalls for contamination.

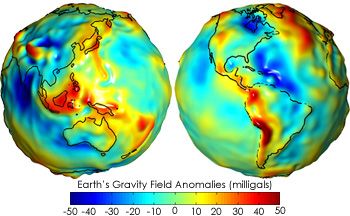

Gravity field anomalies measured through the GRACE Satellite provide information about changes in the Earth’s water levels.

A cohort of science and environmental experts bolsters Last Call’s message with the latest scientific research in the area. NASA scientists at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory are using a program called the Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) Satellite to measure the change in oceans, including water depletion, rise in sea levels and circulation through a series of gravity maps. Erin Brockovich, famously portrayed by Julia Roberts in the eponymous film, appears throughout the documentary to discuss still-ongoing issues with water contamination, corporate pollution and lack of EPA regulation. UC Berkeley marine biologist Tyrone Hayes expounds on what we can learn from genetic irregularities in amphibians found in contaminated habitats.

Take a look at a trailer for Last Call at the Oasis:

Indeed, chemical contamination is the only issue that supersedes overuse as a threat to our water supply. Drugs, antibiotics and other chemicals, which cannot be treated at sewage treatment plants, are increasingly finding their way into the water supply, many of them at the hands of large corporations. Between 2004 and 2009, there were one half a million violations of the Clean Water Act. Last Call doesn’t spare the eye-opening details that will make you think twice when you take a sip of water. Atrazine, for example, is the best-selling pesticide in the world, and the most-used on the US corn supply. Unfortunately, it has also been associated with breast cancer and altered testosterone levels in sea life, and is being investigated for safety by the EPA, with a decision expected in 2013. More disturbing is the contamination from concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs) near major rivers and lakes. Tons of manure from cows, one of which contributes the waste of 23 humans, is dumped into artificial lagoons that then seep into interconnected groundwater supplies.

A scientist holds a bottle of water filtered and purified through reverse osmosis at a sewage recycling plant. Would you drink it?

It’s not all doom and gloom with this documentary, however. Unlike other polemics in its genre, Last Call doesn’t simply outline the crisis, it also offers implementable solutions and a challenge for an entire generation of engineers and scientists. At the top of the list is a greater scrutiny of polluters and the pollutants they release into the water supply without impunity. But solutions such as recycling sewage water, which has made Singapore a global model for water technology and reuse, are at our fingertips, if developed and marketed properly. The city of Los Angeles has already announced plans to recycle 4.9 billion gallons of waste water by 2019. Last Call is an effective final call to save a fast-dwindling resource through science, innovation and conservation.

Last Call at the Oasis went out on DVD November 6th.

~*ScriptPhD*~

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development.

Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

]]>

Comic-Con and the Business of Pop Culture ©2012 McGraw Hill Professional, all rights reserved.

This past weekend, over 130,000 people descended on the San Diego Convention Center to take part in Comic-Con 2012. Each year, a growing amalgamation of costumed super heroes, comics geeks, sci-fi enthusiasts and die-hard fans of more mainstream entertainment pop culture mix together to celebrate and share the popular arts. Some are there to observe, some to find future employment and others to do business, as beautifully depicted in this year’s Morgan Spurlock documentary Comic-Con Episode IV: A Fan’s Hope. But Comic-Con San Diego is more than just a convention or a pop culture phenomenon. It is a symbol of the big business that comics and transmedia pop culture has become. It is a harbinger of future profits in the entertainment industry, which often uses Comic-Con to gauge buzz about releases and spot emerging trends. And it is also a cautionary tale for anyone working at the intersection of television, film, video games and publishing about the meteoric rise of an industry and the uncertainty of where it goes next. We review Rob Salkowitz’s new book Comic-Con and the Business of Pop Culture, an engaging insider perspective on the convergence of geekdom and big business.

Comic-Con wasn’t always the packed, “see and be seen” cultural juggernaut it’s become, as Salkowitz details in the early chapters of his book. In fact, 43 years ago, when the first Con was held at the US Grant hotel in San Diego, led by the efforts of comics superfan Shel Dorf, only 300 people came! In its early days, Comic-Con was a casual place where the titans of comics publishers such as DC and Marvel would gather with fans and other semi-professional artists to exchange ideas and critique one another’s work in an intimate setting. In fact, Salkowitz, a long-time Con attendee who has garnered quite a few insider perks along the way over the years, recalls that his early days of attendance were not quite so harried and frantic. The audience for Comic-Con steadily grew until about 2000, when attendance began skyrocketing, to the point that it now takes over an entire American city for a week each year. Why did this happen? Salkowitz argues that this time period is when a quantum leap shift occurred away from comic books and towards comics culture, a platform that transcends graphic novels and traditional comic books and usurps the entertainment and business matrices of television, film, video games and other “mainstream” art. Indeed, when ScriptPhD last covered Comic-Con in 2010, even their slogan changed to “celebrating the popular arts,” a seismic shift in focus and attention. (This year, Con organizers made explicit attempts to explore the history and heritage partially in order to assuage purists who argue that the event has lost sight of its roots.) In theory, this meteoric rise is wonderful, right? With all that money flowing, everyone wins! Not so fast.

The holy grail of Comic-Con — the exhibit floor, a place of organized chaos where merchants mix with aspiring and current artists, large companies and media empires.

Lost amidst the pomp and circumstance of the yearly festivities is the fact that within this mixed array of cultural forces, there are cracks in the armor. For one thing, comics themselves are not doing well at all. For example, more than 70 million people bought a ticket to the 2008 movie The Dark Knight, but fewer than 70,000 people bought the July 2011 issue of Batman: The Dark Knight. Salkowitz postulates that we may be nearing the unimaginable: a “future of the comics industry that does not include comic books.” To unravel the backstory behind the upstaging of an industry at its own event, Salkowitz structures the book around the four days of the 2011 San Diego Comic-Con. In a rather clever bit of exposition, he weaves between four days of events, meetings, exclusive parties, panels of various size and one-on-one interactions to take the reader on a guided tour of Comic-Con, while in the process peeling back the layers of transmedia and business collaborations that are the underbelly of the current “peak geek” saturation. A brief divergence to the downfall of the traditional publishing industry, including bookstores (the traditional sellers of comics), the reliance of comics on movie adaptations and the pitfalls of digital publication is a must-read primer for anyone wishing to work in the industry. Even more strapped are merchants that sell rare comics and collectibles on the convention floor. Often relegated to the side corners with famous comics artists so that entertainment conglomerates can occupy prime real estate on the floor, many dealers struggle just to break even. Among them are independent comics, self-published artists, and “alternative” comics, all hoping to cash in on the Comic-Con sweepstakes. Comics may be big business, but not for everyone. Forays into the world of grass-roots publishing, the microcosm of the yearly Eisner Awards for achievement in comics and the alternative con within a Con called Trickster (a more low-key networking event that harkens to the days of yore) all remind the reader of the tight-knit relationship that comics have with their fan base.

Business and brand expert (and Comic-Con enthusiast) Rob Salkowitz.

In many ways, the comics crisis that Salkowitz describes is not only very real, but difficult to resolve. The erosion of print media is unlikely to be reversed, nor is the penchant towards acquiring free content in the digital universe. Furthermore, video games, represent one of the biggest single-cause reasons for the erosion of comics in the last 20 years. Games such as Halo, Mass Effect, Grand Theft Auto and others, execute recurring linear storylines in a more cost-conscious three-dimensional interactive platform. On the other hand, there are also a myriad of reasons to be positive about the future of comics. The advent of tablets (notably the iPad) represents an unprecedented opportunity to re-establish comics’ popularity and distribution profits. Traditional and casual fans of comics haven’t gone anywhere, they’re just temporarily drowned out by the lines for the Twilight panel. A rising demographic of geek girls represents a potential growth segment in audience. And finally, a tremendous rise in popularity of traditional comics (even the classics) in global markets such as India and China portends a new global model for marketing and distribution. If superheroes are to continue as the mainstay of live-action media, the entertainment industry is highly dependent upon a viable, continued production of good stories. Movies need for comics to stay robust. The creativity and ingenuity that has been the hallmark of great comics continues to thrive with independent artists, some of whose work has gone viral and garnered publishing contracts.

A group of fans gathered outside the San Diego Convention Center to pay homage to the original reason Comic-Con was established!

Make no mistake, comics fans and enthusiastic geeks. Comic-Con and the Business of Pop Culture is very much a business and brand strategy book, centered around a very trendy and chic brand. There’s no question that casual fans and people interested in the more technical side of comics transmedia will find it an interesting, if at times esoteric, read. But for those working in (or aspiring to) the intersection of comics and entertainment, it is an essential read. Cautioning both the entertainment and comics industries against complacency against what could be a temporary “gold rush” cultural phenomenon, Salkowitz nevertheless peppers the book with salient advice for sustaining comics-based entertainment and media, while fortifying traditional comics and their creative integrity for the next generation of fans. The final portion of the book is its strongest; a hypothetical journey several years into the future, utilizing what he calls “scenario planning” to prognosticate what might happen. Comic-Con (and all the business that it represents) might grow larger than ever, an absolute phenomenon, might scale back to account for a diminishing fan interest, might stay the same or fraction into a series of global events to account for the growing overseas interest in traditional comics. Which one will come to fruition depends on brand synergy, fan growth and engagement, distribution with digital and interactive media, and a carefully cultivated relationship between comics audiences, creators and publishers. Salkowitz calls Comic-Con a “laboratory in which the global future of media is unspooling in real time.” What will happen next? Like any good scientist knows, experiments, even under controlled circumstances, are entirely unpredictable. See you in San Diego next year!

Rob Salkowitz is the cofounder and Principal Consultant of Seattle-based MediaPlant LLC and is the author of two other books, Young World Rising and Generation Blend. He also teaches in the Digital Media program at the University of Washington. Follow Rob on Twitter.

~*ScriptPhD*~

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development.

Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

]]>

Comic-Con Episode IV: A Fan's Hope poster and all film stills ©2012 Wreckin Hill Entertainment, all rights reserved.

Every July, hundreds of thousands of fans descend upon the city of San Diego for a four-day celebration of comics, sci-fi, popular arts fandom and (growingly) previews of mainstream television and film blockbusters. What is this spectacular nexus of nerds? Comic-Con International, of course! From ScriptPhD’s comprehensive past coverage, one can easily glean the diversity of events, guests and panels, with enormous throngs patiently queueing to see their favorites. But who are these fans? Where do they come from? What kinds of passions drive their journeys to Comic-Con from all over the world? And what microcosms are categorized under the general umbrella of fandom? Award-winning filmmaker Morgan Spurlock attempts to answer these questions by crafting the sweet, intimate, honest documentary-as-ethnography Comic-Con Episode IV: A Fan’s Hope. Through the archetypes of five 2009 Comic-Con attendees, Spurlock guides us through the history of the Con, its growth (and the subsequent conflicts that this has engendered), and most importantly, the conclusion that underneath all of those Spider-Man and Klingon costumes, geeks really do come in all shapes, colors and sizes. For full ScriptPhD review, click “continue reading.”

In 1970, comics fan Shel Dorf organized a three-day gathering in San Diego at the US Grant hotel as a fringe gathering for the most enthusiastic amateur comics fans, aspiring artists and writers to interact with comics pros. It drew 300 fans. This was the backdrop against which young Morgan Spurlock grew up in West Virginia, passionately consuming comics and horror films, transported to a different world where everyone was a little bit askew and “weird.” “I wasn’t just a fan,” Spurlock remarks. “I was addicted.” It wasn’t until 2009 that he was able to make his first amateur journey to Comic-Con International San Diego, by now a cultural juggernaut regularly drawing over 150,000 fans, amid a vastly changed (and comics-cultural) landscape. Nevertheless, Spurlock was thrilled. He ran into boyhood idol Marvel animator Stan Lee, and thanked him for all the confidence and creativity he helped to inspire. Stan’s response? “Let’s make a documentary about Comic-Con!” And so, gathering forces with Lee, sci-fi cult icon Joss Whedon, among others, Spurlock embarked on a two-year journey that captured the 2010 Con (the 40th Anniversary edition) in all its glory—including panels, parades, photos, costumes and interviews with notable celebrities that have turned passions into professions. Most of all, however, Spurlock captured the fans.

Costume designer Holly Conrad with her team on the convention floor exhibits at the 2010 San Diego Comic-Con.

To winnow down the most compelling stories for the documentary, Spurlock held a casting call online that drew thousands of submissions. Among them was Holly Conrad, a talented, award-winning costume designer from a small town hoping to win the grand prize at the annual Comic-Con costume show. Knowing her slim odds, especially because of where she comes from, and the importance of making a splash for her career to take off, Holly called Comic-Con a “suicide mission for her future.” Also in a pressure cooker was Chuck Rozanski, proprietor of Mile High Comics, Americas largest inventory and dealer of comic books. Chuck uses the hectic, chaotic, crowded Comic-Con exhibit area to sell rare and collectible comics, comprising a substantial portion of his company’s income for the year, but faces a more fractured Con, with a smaller focus on comics every year. If he doesn’t make a killing at this year’s Com, Chuck knows the future of his whole business might be at risk. Sharing the convention floor with Chuck are comics-obsessed bartender Skip Harvey and US Airforce pilot and family man Eric Henson, two amateur graphic artists also putting their destiny on the line in San Diego. Armed with only a portfolio and a dream, Eric and Skip are hoping to get noticed at the portfolio critique sessions and land a professional design contract with one of the comics representatives. One succeeds (to the preview audience’s delight) and one learns he is a very big fish in a very small bowl, and must cultivate his talent for the greater stage. Intermingled for comic relief is the adorable story of James Darling and Se Young Kang, a couple who met and started dating at the previous year’s Con. James is planning to ask Se Young to marry him at this year’s Con, but must overcome a slew of hilarious obstacles to pull of his nerdy romantic feat.

Chuck Rozanski hangs rare collectibles that he is hoping to sell on the convention floor in a scene from Comic-Con Episode IV.

Comic-Con Episode IV: A Fan’s Hope is a terrific purview into the conflicts and dissent of the modern Con. Hidden beneath the popularity of the yearly event is a schism between older fans who have been coming for years (and feel somewhat lost in the shuffle) and the new fans, such as lovebirds James and Se Young, who may not even necessarily be there for comics events. Longtime attendees such as Kevin Smith admitted that the event has become a “beancounter” with tremendous power to preview movies and television, something Hollywood has noticed and latched onto. One can legitimately forget the presence of comics and the graphic arts at Comic-Con altogether without trying very hard. This presents a huge problem for the poignant storyline of Chuck Rozanski, with whom we empathize as he struggles to sell comics through 4-day event. When ScriptPhD.com asked Spurlock at a recent Los Angeles junket about what surprised him the most, he pointed to the sheer volume of what goes on at Comic-Con, especially the job-hunting aspect of the Comic-Con exhibition floor. His favorite moment in the movie is the comparison of Comic-Con to a Russian nesting doll, with events hidden beneath other events. “I showed the movie to people and they responded that they didn’t even know that went on at Comic-Con! There is something for everyone, no matter what your passion.” Spurlock remarked.

The documentary is at its strongest and most successful when the focus turns to what the essence of what Comic-Con is defined by—the fans. “We all weighed in with what we thought were the most important pieces of the story,” Spurlock says. “But in the end it all came back to the fans.” It is the fans whose enthusiasm drives the growth of events like Comic-Con, however much nostalgia for the past may feel threatened. It is the fans whose passion continues to motivate and drive geniuses like Stan Lee to this very day. That very same passion also launches new careers, as Holly Conrad found. Since the filming of this documentary, she has moved to Hollywood and found successful work as a costume designer on several productions. Lastly, and most importantly, it is the fans who create that magical atmosphere where no matter who you are, where you come from, what you look like, how “out there” you behave, you find total acceptance and camaraderie amongst a group of treasured friends just as passionate and devoted as you are. To Spurlock, the Con “reminds us all of the importance of dreams and of wonder. It’s not just an event… it’s a state of mind.”

Trailer for Comic-Con Episode IV: A Fan’s Hope:

“Making of” featurette:

Comic-Con Episode IV: A Fan’s Hope was released in select cities on April 5, and theaters and video on demand on April 6th.

~*ScriptPhD*~

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development.

Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

]]>

Awake, and all images and screenshots, ©2012 NBC Universal, all rights reserved

As far back as last summer, when pilots for the current television season were floating around, a quirky sci-fi show for NBC called Awake caught our eye as the best of the lot. Camouflaged in a standard procedural cop show is an ambitious neuroscience concept—a man living in two simultaneous dream worlds, either of which (or neither of which) could be real. We got a look at the first four episodes of the show, which lay a nice foundation for the many thought-provoking questions that will be addressed. We review them here, as well as answering some questions of our own about the sleep science behind the show with UCLA sleep expert Dr. Alon Avidan.

Detective Michael Britten (Jason Isaacs) is a middle class police officer living in Los Angeles, with a lovely wife and teenage son, a virtual ‘everyman’ until an unspeakable tragedy—in the show’s opening moments—transform him into a paranormal dual existence. A violent car accident kills at least one member of his family, possibly both (the audience doesn’t yet know, and neither does Britten). Except instead of mourning the loss and moving on, Britten begins a bifurcated dream existence, where in one state, his wife Hannah (Laura Allen) is alive and his son Rex (Dylan Minnette) has perished, and as soon as he wakes up, the opposite is true. Complicating matters further is the mirroring of his lives on each end of this sleep-wake spectrum state. In his ‘single father’ widower existence, he is partnered with gruff police veteran Isaiah Freeman (Steve Harris), and works with no-nonsense therapist Dr. Judith Evans (Cherry Jones). In his other existence, mourning the loss of his son with his wife, Britten’s Captain (Laura Innes) has partnered him with rookie Efrem Vega (Wilmer Valderama), as he works things through with kind, objective therapist Dr. John Lee (BD Wong).

In this still from an episode of 'Awake,' Detective Britten works with partner Detective Freeman (foreground) as his partner from his other reality (background) looks on.

Juggling two worlds might seem complicated (and exhausting) enough, but life for Detective Britten gets even more muddled. Soon sliding with regularity between his two new worlds, he takes various clues from one to solve crimes in the other, even as his behavior in both becomes more erratic and precarious. And while the pilot flawlessly establishes the landscape of Britten’s new reality, future episodes will slowly chip away at it, leaving the viewers with many unanswered questions and mysteries. Is Britten simply dreaming one of these worlds? If so, which is his ‘true’ reality? Is either? Could they both be a lucid dream? Could it be that both his wife and son died? And while later episodes can sometimes veer a bit too much into standard procedural fare, they also offer a thunderbolt of a plot point, suggesting that the car crash that took Britten’s family may have been no accident at all. Given how quickly the last truly ambitious network sci-fi drama (Heroes) veered into absurdity, the steady pacing and erudite plot development of Awake is an almost welcome relief.

We look forward to dreaming for many episodes to come.

Catch up with what you may have missed with this extended trailer:

The sleep science behind the thought-provoking concept of Awake excited us a lot, but we wanted to get deeper answers to some of our most basic questions about the neuroscience of sleep, and just what it is that Michael Britten might be suffering from. To do so, ScriptPhD.com sat down with Dr. Alon Yosefian Avidan, the Director of the Sleep Disorders Laboratory at UCLA’s Department of Neurology.

ScriptPhD.com: Dr. Avidan, for people reading this that may not know very much at all about sleep science, can you give us a brief layperson’s overview of what the scientific consensus is on what sleep is for, exactly?

Alon Avidan: There is no answer. We don’t understand the central reason for why we need sleep. But we know one thing—we can’t do without it. There are about 13 theories that help explain why we sleep. The theories range from needing it to have better memory akin to letting your computer organize files in its sleep mode, so the brain is doing that same thing in your sleep; organizing thoughts, memories and allowing space for new ones to be formed. Another theory is that sleep has a rejuvenating function, essentially for repair, for better immune function. There are other theories that sleep is a hibernation period during which you don’t really need to eat or look for food and it’s a way for you to reserve your energy. This is probably, evolutionarily speaking, back when humans were foraging and needing to conserve energy. There are some theories that sleep is a way for us to synchronize our bodily functions with the Earth. There are really not that many things that we humans are capable of doing during the night, and this is a time for us to synchronize our biological rhythms with that of the Earth.

SPhD: So regardless of which of these theories is true, extreme sleep deprivation has really bad consequences.

AA: Absolutely. When exposed to extreme sleep deprivation, laboratory animals, rats in particular, don’t survive for more than two weeks. They begin to have skin changes, ulcers and they eventually die. In humans, we have situations where people don’t sleep enough. There is a very rare condition called fatal familial insomnia, a condition where patients lose the ability to sleep, and the patient rarely survives beyond a year, maybe six months. But we do know that there are very acute and very chronic consequences that we can observe very quickly [in sleep-deprived patients], including memory problems, planning, and problems with cognitive functions. The chronic issues include inability to regulate food intake, so people end up gaining weight, people end up at risk for diseases that include diabetes, heart disease. And we know that for patients who have primary sleep disorders such as sleep apnea, narcolepsy, insomnia or others, their life expectancy is lower compared to

patients in the same age group.

SPhD: Well, turning to some of the sleep issues in Awake, our main character, Michael Britten, vacillates between two different sleep states, both of which function as his reality, in order to cope with the loss of his wife, son or possibly both. How much do we in fact use our subconscious as a coping mechanism for the traumatic things that happen to us in our lives?

AA: That’s a very interesting point. We know that people who are depressed spend a lot of time in bed, they tend to spend a lot of time sleeping, but their quality of sleep is disrupted. And perhaps it is a coping mechanism for them not to deal with the true conflicts or trauma that are occurring in their lives. What’s very interesting is that in those patients, when they do sleep, sleep is very disrupted. The quality of sleep related to depression or anxiety is really bad. They have arousals, they have awakenings, the duration is short, and the quality of sleep is very light. They often wake up and feel as if they haven’t really slept.

SPhD: What about the dream aspect of sleep in this patient sub-population?

AA: Dreams are when healthy individuals reach the REM cycle (which you know is when we dream). You can have dreams in non-REM cycles as well. What’s interesting is that patients who have post-traumatic stress disorder or anxiety, their dreams are frightening. They’re usually nightmares. Studies show that in many patients who have a very profound trauma like 9/11 survivors in New York City, there was an epidemic of nightmares and stressful sleep experience. Dreams are not normal in patients who have psychiatric disorders, and they are more dramatic and more intense dreams.

SPhD: In the show, Mr. Britten takes clues from one sleep state to solve his crimes in another sleep state (either of which he considers a reality). One of his therapists warns him that doing this is incredibly dangerous because his “unconscious is unreliable.” What do you think the therapist meant by that?

AA: So what’s likely happening to him clinically is that he’s unable to distinguish between sleep and wakefulness. And what is being advised is be more careful not to rely on facts that may be occurring in dreams or wakefulness, because he is not aware which state this is arising from.

SPhD: Is there something to that piece of advice? What about people who regularly swear by premonitions or things they “see” in their dreams?

AA: Clinically, we really don’t see that very often. We don’t see patients relaying a sense of reality between sleep and wakefulness. There is a situation that is neither a sleep state, nor wakefulness, but a combination of the two—the patient has lost sense of what is real and what isn’t. Dissociative fugue disorder is a rare psychiatric disorder where the patient loses their sense of reality, their sense of identity. And it does have something to do with sleep because it’s one of those mixtures of sleep and wakefulness when the patient is unsure of whether they were asleep or awake. It involves extensive memory loss, usually into the wakefulness period, and the person just doesn’t have the capacity to determine what is real and what is fiction.

So, what you are describing with this police officer, he could have this sleep disorder (or something similar) rather than a primary sleep disorder. In the sleep literature, we don’t have patients who strictly come in and lose the perception of sleep and wakefulness and have no other psychiatric issues. What you’re describing is a patient who has a fugue, and may have dream episodes that are very profound, but his underlying primary pathology is a psychiatric one. And there is usually something that crosses this person into the fugue state, and the one thing that does it is usually a major life event that is very stressful. Or a condition in which the patient has such a severe depression that they have no sense of reality because they have a borderline personality and they forget what is real—their sense of reality is so profoundly sad and full of tragedy that they can’t accept it, and are thus creating this lucid state in which they exist more comfortably because they don’t need to deal with the tragedy in their lives.

We want to thank Dr. Avidan for taking time to chat with ScriptPhD.com and give his thoughts on some of the sleep science pertaining to Awake.

~*ScriptPhD*~

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development.

Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

]]>

Physics of the Future images and all content ©2011 Doubleday Publishing.

Dr. Michio Kaku recently consolidated his position as America’s most visible physicist by acting as the voice of the science community to major news outlets in the wake of Japan’s major earthquake and the recent Fukushima nuclear crisis. Dr. Kaku is one of those rare and prized few

who possesses both the hard science chops (he built an atom smasher in his garage for a high school science fair and is a co-founder of string theory) and the ability to reduce quantum physics and space time to layman’s terms. The author of Physics of the Impossible has also followed up with a new book, Physics of the Future, that aims to convey how these very principles will change the future of science and its impact in our daily modern life. (Make sure to enter our Facebook fan giveaway to win a free copy this week!) Dr. Kaku graciously sat down with ScriptPhD.com’s physics and astronomy blogger, Stephen Compson, to talk about the recent earthquake, popular science in an entertainment-driven world, and his latest book. Full interview under the “continue reading” cut.

Hang on Mom, I’m Building an Atom Smasher!

Michio Kaku’s multi-faceted success may seem to be, as Einstein said, the hallmark of true mastery over any advanced subject. But to fully appreciate the extent of Dr. Kaku’s gift for patient summary to the scientifically ignorant, ask yourself when you last saw an internationally respected physicist appear on Fox & Friends.

“It’s not that you want to be this kind of person when you’re a young kid,” the doctor tells me in the middle of his post-quake media marathon: “I’m sure that when Carl Sagan was a young astronomer, he did not say that he wanted to do this. When Carl Sagan was a kid, he read Science Fiction. He read John Carter of Mars and dreamed about going to Mars, that’s how he got his start. For me it was daydreaming about Einstein’s unified field theory. I didn’t know what the theory was, but I knew that I wanted to take a hand in trying to complete it. So you don’t really plan these things, they just sort of happen.”

Dr. Michio Kaku delivering a recent lecture on the future of major earthquakes.

Another breadwinning talent that sets him apart from high-level physics peers is that Dr. Kaku isn’t afraid to address technologies and phenomena that only exist in science fiction. His Physics of the Impossible is a scientific examination of phasers, force fields, teleportation, and time travel. One of the reasons ScriptPhD.com exists is that too many scientists will dismiss such concepts offhand, but Dr. Kaku has made a career of treating them seriously in published works, his radio broadcasts, and his TV show Sci Fi Science on the Science Channel. His latest book Physics of the Future: How Science Will Shape Human Destiny and Our Daily Lives by the Year 2100 puts forth the bold argument that technology will imbue men and women with godlike powers in less than a hundred years, with specific examinations of the current field and estimated times of arrival on things like artificial intelligence, telekinesis (through implanted brain sensors) and molecular medicine that will dramatically extend the human lifespan.

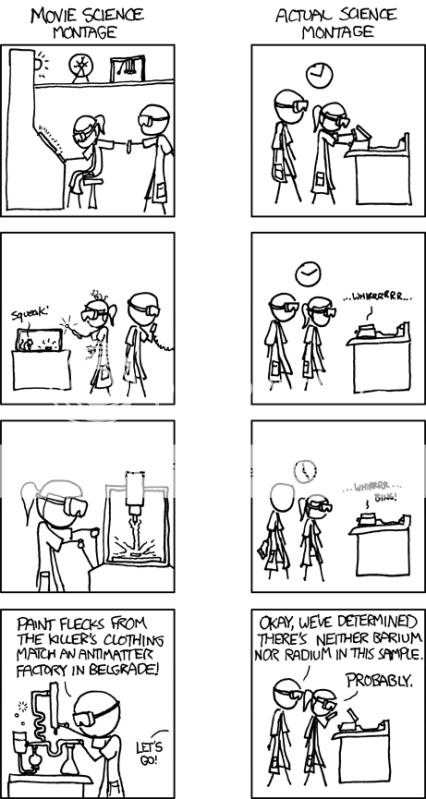

ScriptPhD: Most scientists are very cautious about making the kinds of predictions that you do in The Physics of the Future. Why do you think it’s important for scientists to address the unknown?

Michio Kaku: Because the bottom line is the taxpayer has to decide what to support with their tax money. With funds being so low, we scientists have to learn how to sing for our supper. After World War 2, we gave the military the atomic bomb. They were so impressed they just gave us anything we wanted: accelerators and atom smashers, all sorts of high-tech stuff. And then with the Cold War, the aerospace program pretty much got whatever it wanted. Now we’re back to normal: lean times where every penny is pinched, and we have to realize that unless you can interact with the taxpayer, you’re going to lose your project.

Like what happened in 1993, we lost the Supercollider. That I think was a turning point in the physics community. This eleven billion dollar machine was lost and it went to Europe in a much smaller version called the Large Hadron Collider. We failed to convince the taxpayer that the Supercollider was worthwhile, so they said, ‘We’re not going to fund you.’ That was a shock. When it comes to non-military technology, where the public definitely has a say in these matters, unless we scientists can make a convincing argument to build space telescopes and particle accelerators, the public is gonna say, ‘These are just toys. High tech toys for scientists. They have no relationship to me.’ So it’s important for very practical reasons, if only to keep our grants going, that we scientists have to learn how to address the average person. President Barack Obama has made this a national priority. He says, ‘We have to create the Sputnik moment for our young people.’ My Sputnik moment was Sputnik.

Chasing Martian Princesses

SPhD: What could be the Sputnik moment for the children of today?

MK: We have the media, which is such a waste in the sense that you can actually feel your IQ get lower as you watch TV. But there is the Discovery Channel and the Science Channel and different kinds of programming where you can use beautiful special effects to illustrate exploding stars and Mars and elementary particles. This didn’t exist when I was young. There were no Television outlets. It was just dry, dull books in the library that talked about these things. With such gorgeous special effects on cable television to explain these things, there is no excuse. These are cable outlets where we can reach the public, millions of them, with high technology.

I had two role models when I was a kid. The first was Albert Einstein. I wanted to help him complete his unfinished theory, the unified field theory. But on Saturdays I used to watch Flash Gordon on TV. I loved it! I watched every single episode. Eventually I figured out two things. First: I didn’t have blond hair and muscles. And second, I figured out it was the scientist who drove the entire series. The scientist created the city in the sky, the scientist created the invisibility shield, and the scientist created the starship.

And so I realized something very deep: that science is the engine of prosperity. All the prosperity we see around us is a byproduct of scientific inventions. And that’s not being made clear to young people. If we can’t make it clear to young people they’re not going to go into science. And science will suffer in the United States. And that is why we have to inspire young people to have that Sputnik moment.

SPhD: So you think that science fiction is a good avenue for bringing people into science and getting them excited about it?

MK: We scientists don’t like to admit this, it’s almost scandalous. But it’s true. The greatest astronomer of the twentieth century became the greatest astronomer of the twentieth century because of science fiction.

We may owe the Hubble Telescope, and its majestic imagery, to the inspiration of science fiction.

His name was Edwin Hubble. He was a small country lawyer in Missouri and he remembered the wonderment and passion he felt as a child reading Jules Verne. His father wanted him to continue in law; he was an Oxford scholar. But Hubble said no. He quit being a lawyer, went to the university of Chicago, got his PhD and went along to discover that the universe was expanding. And he did it all because as a child he read Jules Verne.

And Carl Sagan decided to become an astronomer because of Edgar Rice Burrough’s John Carter of Mars series, because he dreamed of chasing the beautiful martian princess over the sands of mars.

Here’s what I don’t like about modern science fiction. A lot of the novels are sword and sorcery. Instead of creating a society for the future, they’re going back to barbarism, they’re going back to feudalism and slavery. Once in a while, yeah, I like to read it, but I get the feeling that it’s not pushing civilization forward.

When I was a young kid , it was called hard science fiction – rocket ships, journeys to the unknown, incredible inventions like time machines and stuff like that, it was less sword and sorcery, less about having big muscles chasing beautiful women and killing your enemies, less Conan the Conquerer. Science fiction stories that talk about the future are much more uplifting for young kids and also point them in the right direction. Sword and sorcery is not a good career path for the average kid.

SPhD: On average, what do you think of the modern media’s treatment of physics?

MK: The Discovery Channel and the Science Channel are one of the few outlets where scientists can roam unimpeded by the restraints of Hollywood, which says you have to have large market share and you can’t get big concepts to people. And one person who paved the way for that was Stephen Hawking and I think that we owe him a debt in that he proved that science sells.

I remember when I wrote my first book, the publishing world said ‘Look, science does not sell. You’re going to be catering to the select few. It’s not a mass market we’re talking about.’ But there were already indications that that wasn’t true. Discover magazine, Scientific American, they both have subscriptions of about a million. And then of course when the Discovery Channel took off, that really showed that there was something that the networks did not see, and it was right in front of their face. And that was science and documentary programming.

It was always there – like Nova was a top draw for PBS – but the big networks said ‘It’s too small, it’s underneath the radar.’ So then with cable television, all the things that used to be under the radar, jumped to the forefront, Stephen Hawking outsells movie stars.

And I think that really shows something. It’s a hunger for people out there to know the answers to these cosmic questions, like what’s out there? What does it all mean? How do we fit into the larger scheme of things in the universe? There’s a real hunger for that, and of course if you watch I Love Lucy all day, you’re not gonna get the answer.

Cavemen, Picture Phones, and Horses

SPhD: On the other hand, there is a basic human instinct to resist scientific and technological change. In your book you describe this as the Caveman Principle:

“Whenever there is a conflict between modern technology and the desires of our primitive ancestors, these primitive desires win each time… Having the fresh animal in our hands was always preferable to tales of the one that got away. Similarly, we want hard copy whenever we deal with files. That’s why the paperless office never came to be… Likewise, our ancestors always liked face to face encounters….By watching people up close, we feel a common bond and can also read their subtle body language to find out what thoughts are racing through their heads…So there is a continual competition between High Tech and High Touch…we prefer to have both, but if given a choice we will choose High Touch like our caveman ancestors.”

I wondered if those weren’t generational changes that we might see come to pass in children who have grown up reading and socializing through screens.

MK: Yes slowly. There is, of course, latitude in the caveman principle. More and more people are warming up to the idea of picture phones. Picture phones first came out in the 1960’s at the World Fair, but you couldn’t touch them with a ten foot pole. People didn’t want to have to comb their hair every time they went online. Now people are sort of getting used to it. It varies, like for instance now we have more horses than we did in 1800.

SPhD: Horses?

M: Yeah! Horses are used for recreational purposes. There are more recreational horses today than there were horses for a small American population in 1800.

Take a look at theater. Back in those days, people thought that theater would be extinguished by radio, then they thought television would replace radio, then they thought the internet would replace television, which would replace radio, movies, and live theater. The answer is we live with all of them.

We don’t necessarily go from one media or one thing to the next, making them previous and obsolete, there is a mix. You could become very rich if you know exactly what that mix is, but that’s the way it is with technology, we never really give up any old technology, we still have live theater on Broadway.

The Silicon Wasteland and Artificial Intelligence

SPhD: Regarding the creation of Artificial Intelligence in The Physics of the Future, you talk about the computer singularity and Moore’s law breaking down in about ten years—

MK: Silicon power will be exhausted for two reasons: first, transistors are going to be so tiny, they’ll generate too much heat and melt. Second, they’re gonna be so tiny they’re almost atomic in size and so the uncertainty principle comes in and you don’t know where they are, so leakage takes place.

SPhD: In the book you are very cautious in your treatment of quantum computers (Presumably the replacement when silicon breaks down) and how long it’s going to take us to develop them – what’s holding that technology back and why shouldn’t we think that they’ll replace silicon right away?

MK: Quantum computers remedy both those defaults because they compute on atoms themselves. The problem with quantum computers is impurities and decoherence. For quantum computing to work, the atoms have to vibrate in phase. But when you separate them, disturbances take place. This is called decoherence, when they vibrate out of phase. It is very easy to decohere atoms that are coherent. The slightest breath, a truck traveling by, even interference from a cosmic ray will ruin the coherence between atoms. That’s why the world record for quantum computing calculation is 3 times 5 is 15 – it sounds trivial, but go home tonight and try that on 5 atoms, take 5 atoms and try to multiply 3 times 5 is 15 – it’s not so easy.

SPhD: What is your definition of artificial intelligence?

MK: Well, that gets us into consciousness and stuff like that. My personal point of view is that consciousness is a continuum, and the same with intelligence. I would say that the smallest unit of consciousness would be the thermostat. The thermostat is aware of its environment – it adjusts itself to compensate for changes in the environment. That’s the lowest level of consciousness – beyond that would be insects, which basically go around mating and eating by instinct and don’t live very long. As you go up the evolutionary scale, you begin to realize that animals do plan a little bit, but they have no conception of tomorrow.

To the best of our knowledge, animals do not plan for tomorrow or yesterday, they live in the present. Everything is governed by instinct, so they sleep, they wake up, but they’re not aware of any continuity – they just hunt or whatever day by day. We’re a higher level of intelligence in the sense that we are aware of time, we’re aware of self, and we can plan for the future. So those are the ingredients of higher intelligence. Since animals have no conception of tomorrow to the best of our knowledge, very few animals have conception of self. For example, you get two fighting fishes and put them together, they’ll try to tear each other apart. When you put them next to a mirror, they try to attack the mirror – they have no conception of self. So we’re higher up. So artificial intelligence is the attempt to use machines to replicate humans.

SPhD: Do you think we’ll need to completely model human intelligence in order to create a satisfactory artificial one?

MK: No, but I think we made a huge mistake. Fifty years ago, everyone thought that the brain was a computer. People thought that was a no-brainer, of course the brain is a computer. Well, it’s not. A computer has a Pentium chip, it has a central processer, it has windows, programming, software, subroutines, that’s a computer. The brain has none of that. The brain is a learning machine.

Your laptop today is just as stupid as it was yesterday. The brain rewires itself after learning – that’s the difference. The architecture is different, so it’s much more difficult to reproduce human thoughts than we thought possible. I’m not saying it’s impossible, I think maybe by the end of the century we’ll have robots that are quite intelligent. Right now we’ve got robots that are about as intelligent as a cockroach. A stupid cockroach. A lobotomized, stupid cockroach. But in the future, you know, I could see them being as smart as mice. I could see that. Then beyond that, as smart as a dog or a cat. And then beyond that, as smart as a monkey. At that point we should put a chip in their brain to shut them off if they have murderous thoughts.

SPhD: The landscape for artificial intelligence seems very fragmented – the research branches in a lot of different directions. Do you think there will be some sort of unification for a grand theory of A.I.?

Could computers and artificial intelligence replace humans, such as the recent supercomputer 'Watson' winning on Jeopardy? Dr. Kaku isn't too afraid. Image courtesy of Carol Kaelson/Jeopardy Productions Inc., via Associated Press.

MK: It’ll be hard, because everyone is working on one little piece of a huge puzzle. Take a look at Watson, who defeated two Jeopardy experts – after that the media thought, ‘Uh oh the robots are coming, we’re gonna be put in zoos, and they’re gonna throw peanuts at us and make us dance behind bars.’

But then you ask a simple question. Does Watson know that it won? Can Watson talk about his victory? Is Watson aware of his victory? Is Watson aware of anything? And then you begin to realize that Watson is a one-trick pony. In science we have lots of one-trick ponies. Your hand calculator calculates about a million times faster than your brain, but you don’t have a nervous breakdown thinking about your calculator. It’s just a calculator, right? Same thing with Watson – all Watson can do is win on Jeopardy. So we have a long ways to go.

Burning Books and Teaching Principles