I’m honored to be joining ScriptPhD.com as an East Coast Correspondent, and look forward to bringing you coverage from events in such exciting areas as Atlanta, Baltimore, and New York City – as well as my hometown of Washington, DC.

And to that end, here is a re-cap of the World Science Festival’s panel “Battlestar Galactica: Cyborgs on the Horizon.” For anyone interested in the intersection of Science and Pop Culture, I cannot promote this event enough. In addition to the panel I’ll be describing, some of the participants included Alan Alda, Glenn Close, Bobby McFerrin, YoYo Ma, and Christine Baranski from the entertainment sector. Representing science were notables like Dr. James Watson (who along with Francis Crick was the first to elucidate the helical structure of DNA), Sir Paul Nurse (Nobel Laureate and president of Rockefeller University), and E.O. Wilson (who is celebrating his 80th birthday in conjunction with the festival).

However, it’s time to return to the subject of this post – BSG and Cyborgs. To read more about the discussion at the intersection of science fact and science fiction, please click “Continue Reading”.

Regretfully, the 92nd Street Y in New York City prohibits the use of any sort of recording equipment, which was not noted on their description of the event or on their policy page, but which I discovered as one of their staff came to scold me while I was testing my camera prior to the inception of the event. So while I took comprehensive notes, I was unable to record the panel in order to provide a full transcript. Nor did I get any photos.[note: and believe me, the reactions shots of Mary McDonnell and Michael Hogan to the cutting-edge science they were showing was worth the price of admission, and would’ve made fabulous photos!]

Faith Salie was the moderator for the event. Geeks may know her best as Sarina from Star Trek: Deep Space Nine. She’s also a Rhodes Scholar, host of the 2008 and 2009 Sundance Festival, and hosted the Public Radio International Program Fair Game. Her knowledge of Battlestar Galactica was impressive, and she’d also done a great deal of background research on the issues related to robotics and artificial intelligence, which allowed her to keep the conversation going, and give fair time to both the science and the scifi.

The science panelists were Nick Bostrom the director of Oxford University’s Future of Humanity Institute and co-founder of the World Transhumanist Association which promotes the ethical use of technology; Hod Lipson, director of the Computational Synthesis Group and Associate Professor of Computing & Information Sciences at Cornell University, who has actually developed self-aware and evolutionary robots; and Kevin Warwick a professor of Cybernetics at the University of Reading in England—unlike Gaius Baltar, Dr. Warwick has a chip in his head. In anticipation of this event, Galactica Sitrep interviewed both Dr. Lipson and Dr. Warwick, and they are interesting reading for more insight into these scientists’ perspectives.

The BSG panelists were Mary McDonnell and Michael Hogan. Faith Salie very aptly introduced Mary McDonnell as “gorgeous” before briefly covering her film credits outside of Battlestar. Vis-a-vis Michael Hogen’s introduction, we learned that he also has X-Files to his credits. [A fact which is sadly missing from his IMDB credits, leading me to wonder which episode??]

The moderator opened the discussion by asking Mary McDonnell and Michael Hogan what life was like after BSG. Mary McDonnell pretended to sob, before acknowledging that “life after death is actually quite wonderful.” She went on to say that dying wasn’t so bad and that she enjoyed being the only actress ever to die first and then get married. At the audience laughter, she then smiled and said she was pleased to see that we “got it” as she made the same quip somewhere else recently and it went over the audience’s head. She pantomimed Adama putting his ring on Laura’s finger after her death in the finale and described the scene as “beautiful,” and her work on BSG, in general as “so compelling.”

She said she was going to miss the cast including “Mikey,” (Michael Hogan sitting next to her) and would miss the direct connection with the culture, and so she was excited by events like the World Science Festival Panel that would allow that connection to continue. She also said that the “fans are the best,” and applauded the audience to which Michael Hogan emphatically joined in.

Michael Hogan’s answer to the same question was that it was very good to leave when it did and “have it sitting the classic show,” and that the experience would stay with him for the rest of his life. He was then asked to set up the premise of the show for those few in the audience that had not seen it. His answer was

In a nutshell, Battlestar Galactica is about an XO who befriends a man who becomes the commander of the Battlestar Galactica and the trials and tribulations of their relationship.

After the audience stopped laughing, he gave the more mainstream description of Battlestar being about the war between the Cylons and humanity and the series opening at the point that the Cylons have just nuked the twelve colonies where humanity lives.

This allowed the moderator to segue into clips from both the Miniseries and the Season 2 episode “Downloaded” where we saw the character, Six, explaining that she is—in fact—a Cylon, and then going through the downloading process.

Following the clips, the discussion turned to the scientists in the panel, who were asked to answer the question: What is a robot?

Kevin Warwick explained that the term “robot” came originally from Karel Čapek, a Czech writer who envisioned robots as mindless agricultural workers. It’s now come to be used much more broadly for that which is machine or machine-like, and that in current usage there’s not much difference between a robot or a cyborg [Note: There are those that would vehemently disagree—a common distinction between the two is that cyborgs are a mixture of both the non-living machine and the organic]. Hod Lipson said that trying to pin down the meaning of that term was a moving target, much like trying to define artificial intelligence.

The panelists went on to talk about who all robots and artificially intelligent systems try to imitate something living—from the primitive systems such as bacteria, to more complex animals as dogs and cats, and now ultimately to humans.

The idea of artificial intelligence and robots that can think for then explored. Hod Lipson said that for the longest time the ability to play chess was recognized as something that was paradigmatically human, but we do now have machines that can easily beat a human at chess. As such the ultimately goal of artificial intelligence and machines that can reason gets moved further and further.

From there, the discussion moved back to Battlestar Galactica, and Faith Salie asked Michael Hogan how he felt upon learning that he was one of the Final Five. They then showed a clip from the Season 4 episode “Revelations in which Michael Hogan’s character, Saul Tigh, discloses his identity as a Cylon to his commanding officer and long-time friend, Bill Adama.

Michael Hogan explained that he disagreed vehemently with that decision, but that it was not something that he could talk the executive producers, Ronald D. Moore and David Eick, out of. He said that for a long time on set there had been joking about who the final five were going to be—knowing that they were going to be picked from those characters that were already established—and had initially thought it was another bad joke. He also said that he’d seen an internet poll at one point asking who fans thought—among all the characters, both large and small—were the final five and he was second from the bottom, while Mary McDonnell was near the top.

When asked about researching his role as XO and later Cylon, Michael Hogan said that researching and getting into a character is part of what attracted him to the job of acting. This led to a side quip about it being a lot of fun to research a cranky man with a drinking problem. More interestingly, he was then asked: How do you research being a robot?

His answer was that he approached it like mental illness. He said he took it as a given that Tigh would already be living in chronic pain as a result of the torture he’d undergone on New Caprica and a functioning alcoholic, so that when he first started hearing the music (that activated him as a Cylon), it wasn’t necessarily a big surprise; it was just one more thing.

It was only after he had the realization in the presence of the other three Cylons that things fell into place, and then it was terrifying for him. He went on to say that Tigh, if not the chronologically oldest person in the fleet [which I guess means counting from the time at which they “awoke” with the false memories on Caprica] definitely had the most combat experience, and as a Cylon was therefore a “very dangerous creature.” To illustrate that, he then described the scene in which Tigh envisioned turning a gun on Adama in the CIC.

Kevin Warwick picked up on this thread and said that this was, “taking your human brain, but with a small change, and everything is made different.” Michael Hogan agreed.

In turn, the moderator then turned the discussion to the work Dr. Warwick is doing in using biological cells to power a robot. In essence, Dr. Warwick has developed bio-based AI. He harvests and grows rat neural cells and then uses them to control an independent robot. At this point in his experiments, he said, they’re only attempting simple objectives such as not getting it to bump into walls. However, as the robot “learns” these things, the neural tissue powering it shows distinct changes indicating that pathways are being developed.

He said he hopes that this research might some day lead to a better understanding of human brains and potential breakthroughs in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s research. There is a video of this robot in action at the London Telegraph story “Rat’s ‘brain’ used to control robot. Other external articles include Springer’s “Architecture for the Neuronal Control of a Mobile Robot” and Seed Magazine’s “Researchers have developed a robot capable of learning and interacting with the world using a biological brain.”

The description of these neuronal cells led then to a discussion of the Cylon stem cells used to cure Laura Roslin’s cancer in the episode, Epiphanies. Mary McDonnell informed the audience that the story line original sprang from what, at the time, was the U.S.’s resistance to stem cell research. The moderator then decided to bring a little humor to the discussion by saying, “So, Laura’s character as near death, but your agent finally worked out a contract.”

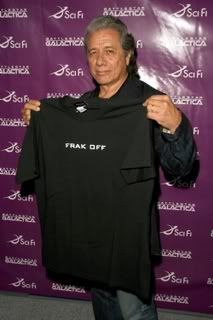

Mary McDonnell laughed and said, yes, she was near death but she finally decided to stop pushing for a trailer as big as Eddie’s [Edward James Olmos] realizing that “no one gets a trailer as big as Eddie.”

Returning to the discussion of the plot, Mary McDonnell noted that what really fascinated her about this storyline was Baltar. She said that it was the first time we saw “the beginnings of a conscience” in him, and that as a result of that he took “profound action.” She then further described the course of cure based in the stem cells from a half-human/half-Cylon fetus, and concluded with saying, “Not to say I got up the next day and became a Cylon sympathizer . . .”

The panel discussion then segued to a discussion of the work being done by Hod Lipson on robots’ abilities to evolve—in a Darwinian sense—and to breed. Using modeling and simulation tools and game theory, Dr. Lipson is creating robots who self select based on desirable traits and from generation to generation become stronger, more mobile, and better adapted to their environments. His slides included a reference to the Nature article “ Automatic design and manufacture of robotic lifeforms.”

Dr. Lipson noted that many of the parts used in these robots are created using 3-D printing, which is, in itself a rather new and exciting technology that really excited not only the moderator, but also Michael Hogan and Mary McDonnell. What wasn’t discussed, is that beyond allowing robots to design their own parts, this technology has a lot of practical applications. One of those that has the greatest potential to positively impact people is that of prosthetic socket design.

In order for the robots’ evolution to proceed more swiftly and realistically, Dr. Lipson explained that he’s given them the ability to self-image. Yes, the robots are SELF AWARE. He showed a video (a variant of which can be found from an earlier talk on You Tube) which showed a spider-like robot experimentally moving its limbs and as it did so, developing an idea of what it looked like. At each generation, the robot’s idea of what it looked like got more and more accurate, and its ability to move grew more and more precise.

The researchers then removed one of the robot’s four limbs, and Dr. Lipson described how the robot became aware that its limb was missing and even adapted to walk with a limp This elicited sounds of sympathy from both the audience and Mary McDonnell until both the audience and Ms. McDonnell realized we were sympathizing for a machine. If this doesn’t show how the very blurred the line has become, I’m not sure what does!

Dr. Lipson’s other research involves robots that can self replicate. His slides for this portion referenced the Nature article, “Robots: Self-reproducing Machines.” These robots are modular and when given extra modules will, rather than adding to their own design, create a copies—exact replicas. (Yes, perhaps Battlestar Galactica wasn’t that far from the mark when it posited that “there are many copies.”) The reaction of both the non-science panelists and the audience to the video that was included of the tiny robots using extra building material was really that of astonishment. Michael Hogan spent much of this discussion watching the monitor with his mouth agape in wonder.

To the amusement of about half the room, the moderator than asked Dr. Lipson if perhaps he could “design fully evolved robots so that the creationists have something to believe in.” While an easy laugh, it also does raise the question that follows. While the moderator asked posed it as, “Are we in a paradigm shifting moment,” it could easily also be tied back to the Battlestar Galactica universe and Edward James Olmos’ (as then Commander Adama’s) speech in the miniseries when he suggested that perhaps in creating the Cylons man had been playing God.

The panelists noted that machine intelligence does not have the same constraints as human intelligence. A human brain consists of, as one panelist put it, “three pounds of cheesy grey matter” and performing functions takes 10s of milliseconds. A computer chip is already orders of magnitude faster. When asked to pinpoint the point at which human-level AI could be accomplished, the panelists were originally reluctant to give a time frame, though with great reluctance acknowledge that it could happen within our lifetime.

Hod Lipson suggested that the next step—that of superhuman AI—would be substantially shorter than the first step of accomplishing human-level AI.

This discussion then naturally led back to Battlestar Galactica’s dystopic view of a potential robot-led uprising. After all, if, as the scientists on the panel think that the accomplishment of an artificial intelligence that is smarter than humans is not only possible, but probable, what is the likelihood that this artificial intelligence is going to want to do what its human creators tell it to do?

The panelists dodged that question, saying that they found that part of the science of BSG highly unrealistic

It’s entirely improbable that [the Cylons] would begin by killing off all the ugly people.

They then discussed issues relating to the internet and networking relative to the evolution of robotics, which was another area that was of grave concern in the universe of Battlestar Galactica. The scientists all agreed that that aspect of BSG and Adama’s fear of networking was highly realistic. They said that the driving force for robotic evolution was really the software, because at this point given that many computers have multi-core processors independent computers, in some ways have mini-networks inside them. They also said that networking itself is a highly vague concept and that “it’s not like you can just ‘turn off’ the internet.”

A clip from the third season episode “A Measure of Salvation” which showed the discussion among the characters surrounding the potential for Cylon genocide vis-a-vis a biological weapon then followed. Mary McDonnell noted that in addition to the many ethical questions that were raised relative to whether or not one can realistically commit a genocidal act against “machines,” one of the remarkable points of that episode for her, was the scene that followed wherein Adama turned the choice over to Roslin (parenthetically, Mary McDonnell noted “as he often did with difficult decisions”). She said that it was fascinating to her to later watch Laura’s (parenthetically, again, she said, “her own”) face during that moment she ordered the genocide—because although Laura was did what she did for the same “reason she did almost everything” in making a choice for survival, that underneath that she could see a “pure cynacism”—the type of which is at the root of any difficult decision that you “ethically disagree with but do it anyway.”

When asked by the moderator whether they were given the opportunity to provide feedback on the direction their characters were going, and Mary McDonnell and laughed and said they were “the noisest bunch of actors.” She said that it was particularly difficult for her at the beginning of the series because she had to shift a lot of her point of view in order to adapt to Laura Roslin’s own changes and many of the more “feminine aspects had to shift into the back seat.” She described a point at which she and [executive producer] David Eick were trading angry emails, and [executive producer] Ronald D. Moore had to butt in and send them back to their respective corners.

She followed that by saying that she’s never before “had the privilege to be inside something that engendered so much discourse.” Both she and Michael Hogan said that while they rarely connected with the audience outside of special events, that Ronald D. Moore was profoundly aware of the audience’s reaction and feedback and did sometimes take that into account, so that there was truly a “collective aspect” to the show. And they both again applauded the fans and the audience.

From that, the discussion then returned to the original subject of the clip, and that of “robot rights,” and whether it was possible to provide “rights” to robots and whether they had subjective experiences and a sense of self upon which the foundation for such a discussion should be lain. Dr. Lipson said he did envision a day where “the stuff that you’re built out of is no more relevant than the color of your skin,” and that in many cases “machines are not explicitly being programmed and to that extent it’s much closer to biology.”

Dr. Bostrom, who served as the ethical check necessary to balance the scientists’ curiosity cautioned against the “unchecked power” of the sort that comes with this technology after so the other two scientists suggested that given that AI lacks a desire for power, that it is not something to be generally feared.

Dr. Bostrom further noted that all self-aware creatures have a desire for self preservation, and that perhaps most relevant to the discussion of BSG was the use of AI in military applications, where the two goals were “self preservation” and “destruction of other humans.” He suggested that the unpredictability of evolved systems might be the very reason not to do it.

He noted that the “essence of intelligence is to steer the future into an end target,” and that looking at BSG as a cautionary tale, it is necessary to remove some of the unpredictability.

One of the other panelists noted that they regarded science fiction as “not so much a prediction of what will happen in the future as a commentary on the present,” to which Mary McDonnell emphatically nodded.

The moderator then asked Dr. Bostrom about his work in “Friendly AI.” He described it is generally working to ensure that the development of AI is for the benefit of humanity, and that he regrets that this pursuit has “very little serious academic effort.”

In a dynamic change of pace, the moderator then wanted to devote some time to Kevin Warwick’s experiments into turning himself into a Cyborg. Video of some of this can be found on YouTube and he’s also written about the experience in his book, I Cyborg. He described a series of experiments, one in which he implanted a chip in his head which was implanted so as to allow him to be linked to a robotic arm on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean and actually feel and experience what this arm was doing, including the amount of pressure used.

He also described a second experience where a set of sensors implanted in his wife’s arm allowed him to experience and feel what she was doing from across the room, which is written up in IEEE Proceedings of Communications as “Thought communication and control: a first step using radiotelegraphy.” The description of this experiment caused a great deal of curiosity for all involved as they tried to understand exactly what he was feeling and how he felt it, and at one point even Mary McDonnell started asking questions with a great deal of amusing innuendo.

His final experiment involved providing his wife with a necklace that changed color depending on whether he was calm or “excited” based on biofeedback it received from a chip in his brain, and again led to a great deal of innuendo.

The moderator drew her portion of the panel to a close by asking the actors what they would take from their experience on BSG. Mary McDonnell said that

I no longer suffer from the illusion that we have a lot of time. On a spiritual and political plane, I’d like to be of better and more efficient service, because it really feels like we’re running out of time.

Michael Hogan said there’s nothing he could say that would improve on Ms. McDonnell’s statement.

There was then only time for two questions from the audience. The first question was whether or not AI should be regulated by the government. Dr. Lipson answered that indeed it should not, and that instead it should be open and transparent. Dr. Warwick added that based on the U.S.’s democratic system, that AI belongs to all people regardless.

The other question from the audience was directed toward Mary McDonnell and was whether or not she was surprised to learn that she wasn’t as Cylon. Ms. McDonnell answered that she felt it very necessary that Laura remain on the “human, fearful plane” and that to do otherwise with her would’ve been a cruel joke. As such, she wasn’t surprised by her continued humanity.

~*PoliSciPoli*~

]]>

Remember back during our complete coverage of the Battlestar Galactica panel at the Paley Television Festival when I said that event would probably be the last significant gathering of on and off-screen talent from the show? Well, I may have been lyingpremature in my declaration. It’s no secret that in the annals of television history, Battlestar Galactica will rightfully take its place as one of the most sophisticated, abstruse, demanding, and thoughtful shows to ever grace the silver screen. No issue or hot-button topic was off-limits to the writers: war crimes, torture, genocide, abortion, religious conflict, human rights, the rule of law, anarchy, the very essence of humanness. Though an action-adventure space opera to its core, BSG integrated storylines eerily germane to the times we live in, and transcended its medium in the process.

In recognition of these tremendous achievements, and in a television first, the United Nations hosted an invitation-only panel back on March 17th in the hallowed Economic and Social Council Chamber composed of UN representatives and officers, cast members Mary McDonnell and Edward James Olmos, and executive producers Ronald D. Moore and David Eick. As a pilot project for its Department of Public Information’s Creative Community Outreach Initiative, the UN hopes to partner more often with the international film and television industries to raise awareness and foster discussion of prevalent global issues. Unfortunately the first United Nations event took place at their headquarters in New York and we had to miss it (sadly, the ScriptPhD is not yet bicoastal). But luckily for us, the United Nations partnered with the Sci-Fi Channel to host a West Coast rebroadcast from Hollywood Thursday night. As a part of the Los Angeles Times’s annual pre-Emmy Envelope Screening Series, LA Times writer Geoff Boucher moderated a panel that once again welcomed McDonnell, Olmos, Moore and Eick, and UN representatives Steven Siguero and Craig Mokhiber.

Amid a chorus of enthusiastic fans and “So say

we all!”s, a lively and vibrant discussion ensued about torture, enemy combatants, race, and the upcoming Battlestar Galactica: The Plan TV movie event. ScriptPhD.com is proud to bring you complete coverage.

To read a transcript of the LA Times Envelope Battlestar Galactica Discussion Panel please click “Continue Reading”.

Geoff Boucher: Thanks for coming! Battlestar Galactica is my favorite show. I think it’s the best hour of television. So say we all?

Audience: So say we all!

Geoff Boucher: Thanks for coming here tonight. Tonight we’re going to celebrate Battlestar Galactica but we’re also going to do a little more than that. We’re gonna talk about The Plan. Maybe we’ll even see something? And we’re gonna talk about Caprica. And also we’re going to obviously have a discussion about how this show not only resonates and reflects what goes on in this very serious world that we live in, in our real world, with very dire human rights issues that we see all over the globe right now. But it actually may spur us to do something about it. Maybe we can find ways to take an artistic conversation and turn it into a real-world application. So with that spirit, we’re gonna have a fun night. I’m not a terribly organized person, so this is gonna be a little more jazz than marching band, but I hope you guys enjoy the spirit of the night. And if we flub anything, just smile and clap. Okay, you know, we have some famous people here tonight. And we have two very special guests that I want to bring up first. They’re joining us from the United Nations in New York. And first of all I have to say, when it comes to weighty, international conversation, you know really serious stuff, what says that better than Hollywood and Highland? Could someone go get Spongebob from the sidewalk [on Hollywood Boulevard] because we gotta talk a little waterboarding.

[audience laughs]

GB: Sorry. OK. We have two very distinguished guests for this event here tonight. Steven Siguero, senior political affairs officer in the Office of the Undersecretary General for Political Affairs at the United Nations and Craig Mokhiber, deputy director of the New York office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, and I’d like them to join me now on the panel. And of course we have two of the architects of this wonderful Battlestar universe, which has taken us to so many places we never expected, including Earth, let’s welcome David Eick and Ron Moore. Battlestar Galactica has a lot of heart in the show, but if you had to look at the emotional center of this universe, and all the challenges that beset these poor, desperate people, all you’d have to do is look at the two people who shared a love story in the middle of it all, and we’re very, very lucky to have two wonderful, wonderful actors with us tonight, Mary McDonnell and Edward James Olmos. I think we’re going to start by watching a very nicely put-together introduction to the show and the conversation tonight. So are we ready with that?

[clip of Battlestar Galactica’s greatest moments]

GB: Of course, preceding this event was the United Nations event that we’ve heard about. I’m sure many of you watched it. I had a chance to talk to Mary about it afterwards, I saw you at the screening of the finale, of the show, which was a fantastic—by the way, let’s hear it for that finale.

[wild applause]

GB: Mary, at the finale, you were telling me how you seemed to be almost pulsing with excitement about that day and what it promised and brought up. Give us a little bit about that. Maybe a snapshot memory and maybe an emotional memory of that day.

Mary McDonnell: Well, I think it was sort of a feeling of exhilaration in that first of all, it was such a pleasure and an honor to be with these people who are so brilliant and devoted and have such a perspective to offer us and to give us the comfort of their ideas and the sort of brazen commitment of their ideas in a public forum. To be part of that and to be inside

the UN was a great privilege as an artist. Because at the core, what we really want as artists is to be brought into the culture and to be able to serve. And so I think that the event that gave me the exhilaration was the [opportunity to give service] with people who are truly serving. And that was quite an amazing feeling. And it’s great to be back with you.

GB: It’s amazing how this show presents itself for scrutiny on very serious matters. There’s a lot of shows that they merely entertain. This one goes far, far beyond that. Craig, you have a presentation of sorts. You’ve sort of articulated in your own mind some of the ways that this show reflects and resonates with what’s going on in the world today. Could you maybe tell us a little bit about that?

Craig Mokhiber: Sure, with pleasure. I’m not sure I have a presentation—

GB: You can say you have a take on it or the star power that Spongebob would have if he were here today.

[laughter]

CM: It’s kind of hard to have a take on this, and to make linkages between Battlestar Galactica and the kinds of things that we work on every day in the United Nations. I mean, people talk about Battlestar Galactica as science fiction. It might be, and there might be some science in it, but from our perspective, it’s not a heck of a lot of fiction. If you do the sort of work that the hundreds of UN human rights monitors around the world do, you will realize that it is more allegory than it is fiction in the true sense of the word. Our organization was established sixty years ago, over sixty years ago, with a very particular idea in mind, the idea that you can have an international order in which the purpose of government and the purpose of society is to provide freedom from fear and freedom from want, and what more central theme in the many seasons of Battlestar Galactica can you find than freedom from fear and freedom from want? But the timing I think of this show is particularly interesting, because it is a show that was enjoyed by all of us during a period when we were especially worried about the state of human rights in the world. So many of the themes that we address every day in our work found their way into the story of Battlestar Galactica. During the UN Panel, I actually told the creators that they owe royalties to the UN because we were so familiar with so many of those themes. And I don’t have to rehash them for this audience. You clearly know the show very well, and you know the state of the world in which this show has been shown.

And the war on terrorism, for example, when we have seen for many years now the most basic and fundamental ideas of human rights being challenged in the name of some very old-fashioned notion of security. We had thought that we had reached a point in civilization where security meant human security, where every individual had a right to be secure and that security meant freedom from fear and freedom from want. Not old-fashioned, archaic notions of state security, where security is whatever the government says. But security that says that I have a right to be free from the fear that terrorists will hijack a plane and crash it into a building and kill me, but I deeply have a right to be free from the fear that my government will drag me away in the middle of the night and throw me into a dungeon because it doesn’t like my race or religion or my political opinion. Or at the same time, this problem of the growing number of chauvinisms or concept of ‘the other’ that we see, as people are identified according to, I always hesitate to use the word race around Edward because he and I agree that there is no such thing as race, but all of the ways that societies seek to identify ‘the other’ and in doing so to dehumanize them in order to destroy them. I made a comment during the panel at the UN that at any given moment in history, each one of us is a Cylon, each one of us is a colonialite. Today we can be the victim, tomorrow we can be the victimizer. Unless we live under a common set of rules that are applied to everybody that protects human dignity, that protects us from freedom from fear and freedom from want. And that’s what the international human rights movement is all about. That’s what UN Human Rights work has been about, and it’s very much the theme that there have been so many of the series that we’ve all enjoyed so much.

The piece that I think hit home the most for us was the way the series captured the concept of moral relativism, or exceptionalism, this idea that okay, there are these rules, these quaint ideas about human rights, but it’s a different world, and we’re under threat, and it’s an emergency, and there are special circumstances. Therefore, in this case, maybe we have to torture people and waterboard them, for example. That’s a very dangerous, slippery slope that I think the show demonstrated very well. There are very few, a very small set, of human rights that are so absolutely universally agreed upon as to prohibit their violation in all circumstances. Torture is one of them. What are we to think that we live in a moment in history when people are debating whether or not we should torture in the name of terrorism.

[audience applause]

CM: This idea of exceptionalism, this idea that you can find excuses, security excuses for torture, is the same idea that has been used to justify slavery on economic grounds and genocide on political grounds. You can make those arguments but it’s unacceptable under all circumstances and testing those very difficult issues through boring UN documents is one way to do it, but doing it in popular media and in an excellent television program like Battlestar Galactica is a much more effective way of doing that.

GB: Ron, I wanted to ask you, let’s hear it again for Ron.

[audience applause]

GB: It’s well-recognized that you came into this show with a manifesto of sorts, a belief that the show had to embrace a certain amount of realism and break away from the tropes of science fiction, some of the things that kept science fiction back, especially on television. But tell me about the political stuff, the idea that as the show went along it would really be torn from today’s headlines and tell the issues that you really don’t see on most science fiction shows.

Ronald D. Moore: Well I think from the outset one of the first things that David [Eick] and I talked about was the fact that we wanted the show to be relevant. That we thought, you know, let’s do a science fiction show that isn’t purely escapists, that isn’t about people and civilizations that mean nothing to us. Let’s do a show that’s more along older and more traditional science fiction that’s sort of common to the audience and contemporary society through this interesting prism. And I think that while we’re both sort of historians and science majors, I think we also decided from the outset that the show was not really a soapbox for our particular political viewpoints. You can’t help but let your own worldview leak into what you do. I don’t think any of us can fool ourselves into thinking that it wouldn’t, but it was important to us that the show was not really just an opportunity to say “This is what we think the right answer is, and this is what the answer to these difficult political and moral questions are.” It was really an opportunity to examine them, to ask questions or look at them from a slightly different point of view, and sort of say, “Here’s a group of characters that we are now going to ask you to invest in. This is what these characters decided in these different decisions, and make of that what you will.” I think as the show, as we got into the series, is when we started dealing with more and more of these kinds of things. I tried very hard not to make it simply a way to sort of attack the Bush Administration, to advance a sort of agenda. And I sort of took the approach that we were going to sort of try to represent all of the sides of these debates fairly. We would try to sort of take [Abraham] Lincoln’s phrase of “With charity for all, with malice towards none” and make that what the show is about. We were gonna give everybody their time and their place, and we would give these very difficult, very thorny issues a hearing and sort of watch how characters like Adama and Laura Roslin would grapple with these issues but not pretend that it was a simple or a political instance one of the two. We didn’t want to say, “Well the Liberal point of view is this, therefore the show is going to promote that.” And at the end of the episode, the captain will say, “This is what the right answer is.” It’s always going to be difficult to get to anything resembling a right answer in these very complicated sort of questions.

GB: Eddie, it seemed to be on this show, that a lot of times whatever the character believed in the most was eventually ripped away from him. It’s like everybody was broken down by the circumstances around them and testing. Tell me a little bit as an actor, it must have been pretty phenomenal—just think of it, the relationship with Tigh, and the different things that you went through, that your character went through with your son, and the way things are flipped around. This show really tests the boundaries of what science fiction could be on television.

Edward James Olmos: Well, I think it tested our humanness towards one another. I think I had most response from Admirals and military hierarchy when they would come up and say thank you to us because of the fact that we had allowed them to see themselves in the way that they really are, in the respect of having moments of complete devastation which were left laying on the ground either drugged up or in complete chaos under the weight of what they’d done. And, you know, many of us never see that because they won’t do that in front of people. And they’re strong and as far as anybody is concerned this guy is like a rock. And I think that’s really the beauty of what the show did. To everybody, not just to Adama, but to everyone. Laura, pffft, [EJO pulls an imaginary trigger against his head]

[audience laughter]

EJO: As well as Starbuck. “We’re going the wrong wayyyyyy!” No shit, Sherlock! For years, we’re going the wrong way. But I gotta say, it would never have been this way had not the writers in this media, especially on the show led by both Ron and David, and the superb writing of the highest caliber, everyone involved with it, said, “Yes, you can criticize anything.” But I will say that I am so honored to have been able to get those scripts, because I was like you. I was waiting for the next one because I had no idea what was going to happen. No one did. No one knew, and I mean, I never complained once. If anything, they would complain to me about taking it too far. They’d say, “Oh, you really want to go there?” and I’d say, “Yeah. I’m an alcoholic as far as I’m concerned. You want me to take a drink? Watch.” And as we got into the third and fourth season, I took it away. I mean [Adama] had lost it. And it was the sadness, because there’s what our core, our ADMIRAL, and you know he was completely gone. Many times he was left on the ground, and yes it was devastating, and it hurt everybody, as I’d watch I might say, “Well this is really not healthy for everybody to see. You know, we don’t really want to know this about ourselves.” And yet, it was what drove the UN to say, “You know what, thank you very much guys. And we want to thank you very much for presenting to the world subject matter that we have been trying to understand and we can’t do it alone and you can’t.” But now the UN in the last two times that we’ve been together, has hit a new level of understanding between all of us, especially, that were inside of the show and saw us go to the UN. And the rest of the world, because the blogging and the amount of participation on the internet and watching at the UN has been monumental. It’s been unprecedented. I don’t think the UN would have gotten this kind of an understanding had it not been for the courage of them to say to us, “Yeah we like Battlestar just like you do.” I mean, you’ve really put yourselves out there from the very beginning of this show to say critically, “This could be the finest television show EVER.” And I just sit back and go, “Oh my goodness.” But it came down to one thing. It came down to the writing. Period.

[Audience applause]

GB: There are people, I am told, tweeting, even as we speak. I’m speaking, they’re tweeting. This is going on, there’s obviously a great focus on the internet, this is going to focus beyond this. Steven, there’s some other ways that the ideas and discussions tonight are going to move forward. Will you tell us a little bit more about that?

Steven Siguero: Sure, I’m here representing the Department of Public Information, a whole new department, that is the department of political affairs. And just so that those in the audience know more about the UN, I trust that you all have heard of the UN. We have a good world presence. We feed 90 million people around the world in 70 different countries. We are currently taking care of refugees in several different continents, including the Swat Valley in Pakistan and of course in Gaza. And we led the charge to combat cholera, we led the charge to eradicate small pox and polio, we’re fighting for gender equality and much like on the show, it is a completely engendered environment where there is complete equality between the sexes, which is something that the UN sees as an ideal. So the UN has a presence, and it has a breadth and complexity of the issues that we deal with. And it has always been a challenge for us to communicate that to a mass audience and to get the support that we need to fight the battles that we all really share. And so this type of an initiative is something that we’ve been thinking of for quite some time in the organization. We saw films such as “The Constant Gardener” or “Blood Diamond” or “The Interpreter”, which was the leading edge of interacting with the UN. Obviously, the UN had the circumstance from it’s creation until the 90’s, the early part of this century, of bit player or prop if you will in several films. But over the last decade, we really started to become interactive with the creative community, and I think in the last year or so we really wanted to increase this focus. And just seeing the power of Battlestar Galactica and seeing what could be done through this media, it’s much clearer to us that you are much better at communicating some of these themes than we are. And it’s like, we’re very good at doing our boring documents and setting norms and setting standards, negotiating around cables, but we haven’t really hit the way to communicate that until this moment. And as Eddie said, with the Battlestar Galactica event back in March, we hit whole new groups of people that we really never thought we could access or that would listen to some of the things that we were trying to talk about. And so we’re really very, very grateful.

GB: David tell us a little bit about, you know there’s so many things that the show touched on, social issues that we’ve talked about, the torture episode that people have a hard time forgetting about, it was very searing. Maybe pick one or two things that you saw during the show that you would hold out as a proud view of the way that it was handled or the nuanced way or provocative way?

David Eick: Well, most of the things that were created and now are being analyzed by the United Nations and great performers were dreamed up in sports bars. It’s surreal for me to contend with that, but I think Ron touched on this earlier, we were averse to attempting to adapt headlines. That wasn’t what we wanted to do. We didn’t want to make it feel like we were taking the New York Times stories and turning them into episodes. There was a sense of course, of this fairly restrictive Administration and a period of time when it seemed like human rights and freedoms were being restricted and that we were being misled and that we were not clear about why we were doing things that we were doing and why our sons and daughters were being lost. And I think that that sort of just uniformly indoctrinated itself into the work, and the work was all about drama and about trying to make people feel what we were feeling in the room, what we were feeling as we discussed things with each other and it wasn’t that dramatic, it wasn’t that situationally specific. It was really about just trying to tell good stories and finding ourselves amidst this period of time in America where those good stories were being informed by the sick world and an upsetting world. And in the final analysis, I think that that has bared itself out, that there’s a sickness and a darkness and a tortured quality to the heroes of Battlestar Galactica that, if we had done this show ten years later, never would have happened.

GB: That’s very interesting. September 11th certainly, with the destruction of Caprica, it is hard not to watch that episode and not think about that. We’re going to have another clip here in a minute, but first I wanted to ask about looking forward with Caprica, Caprica anyone? [See the ScriptPhD review here]

[audience applause]

GB: One of the boldest things about the show that I believe, and sophisticated, was its use of religion and the way that it set people apart from each other by their most basic belief. We saw a little bit of that already with Caprica moving forward. Ron, can you tell us a little bit about religion and Caprica?

RDM: Well it’s one of the core concepts of the show. Because anyone who saw the pilot can tell you, it’s sort of about the creation of the Cylons and it’s about how the clash of two very different theological point of views. There was a group of people in the colonies that believed in who they felt was the one true God, and the rest of the colonies were polytheistic, and the clash of these two ideas that sort of helped to inform the how and the why of the Cylons’ ultimate coming into being, and as the show progresses, as the series goes, that idea is very much part of the show. The story of how these two fundamentally different approaches to a worldview and how they collided and what happened in that collision, it is really part of the story of Caprica.

[brief clip of torture and conflict scenes in BSG]

GB: You know, the world is so messy, and brutal and with all these different tugs and forces between us. After these things are over, after these terrible events happen, there is always this urge for accountability. That’s part of what you guys are working towards, figuring out a definition of that isn’t it?

SS: Yeah, that scene [the Cylon Leoben being tortured with the bucket of water by Starbuck] was particularly impactful when I saw it a few months ago, but one of the things that comes up most strikingly is if everybody is accountable, how do you actually purge the guilt? And I think this is something that we face quite often in our work. When I think of that scene I think also of the earlier part of it where Lee Adama is talking about being in an impossible situation and what would you do in an impossible situation when your choices aren’t so clear? And I think the big question for the UN and for many of our missions in the field is trying to reconcile this challenge between peace and justice and do you make political compromises to assure some level of stability? Some level of security for everybody, while burying the accountability issues, which will only in the end come up later? And I think that is something that we always see. We have this new mechanism, the ICC, the International Criminal Court. It’s running around the world trying to develop the concept of justice, but there’s challenges every day. I’ll let someone else speak.

CM: No I think Steven said it very well. For the United Nations, peace and justice are two sides of the same coin, and we set up some of these false dichotomies that you have to choose now between security and human rights. Peace or justice. An endless list of ultimately false dichotomies. You set yourself up for failure in advance. And I think what we learned from conflict situations around the world is you don’t develop peace processes and solutions that are fundamentally based upon human rights where there is redress for the real grievances of victims, not vengeance, but here we’re talking about accountability under the rule of law. And there have been many, many experiences in countries that have been torn by war and mass atrocity of so-called ‘transitional justice’, where you know broad consultations with communities that have been most affected are held to find out what is their concept of justice? What is necessary to bring this society to a place where it can begin to heal? And one thing that we know for sure is that impunity does not serve the end of conflict. There is a temptation, always, to say, “Well, we’ve had a very bad situation here, lots of mass atrocities, but let’s look forward. Let’s move on.” Unfortunately, those things buried in the closet have a tendency to come back and to erode any effort at reaching normalcy, at reaching a sustainable peace for example. And so accountability is a part of reconciliation. Accountability is a part of restoring the rule of law. And societies all around the world are struggling with the same kinds of issues that we saw in this clip. I was very happy to see my boss [the UN Secretary-General] quoted at the end there, by the way.

GB: I’m sure he’ll read that tweet. You know, I guess when it comes down to it in times of great calamity, in times of great peril, there is a tendency to maybe lose ourselves. I guess that’s maybe when we should try to find ourselves. Our true selves, to find our spirits and how we want to be judged in our own mind and by the world. For Roslin and Adama, these two characters at the very heart of the show, they were lost and found so many different times, Mary and Eddie, maybe if you guys can take a little minute and tell us about the journey for your character, and maybe just some of the things that fit into this entire conversation that we’re having. Mary can you talk a bit about Roslin and her journey?

MM: Absolutely. I really think that these ideas are central to what playing Laura Roslin felt like. It was a constant negotiation between a deeper, more wise, perhaps slightly more evolved spiritual person living inside a very frightened human being who felt very responsible for an idea, which was to save the human race or at least to make it possible for the human race to continue. What was hard about playing it was almost like reversing one sensation, instead of sort of having a straight back and an open front, I felt like she had a closed front and a broken back, because of the inability to get beyond the idea of saving and defending due to fear of loss and fear of death ultimately, when it comes down to it. And really to get beyond that and see something more progressive in the dialogue rather than bringing it to the airlock, was a phenomenal opportunity for me as an actress to sort of experience the pain of a limitation like that. And I think that that working through feeling that there isn’t another choice and learning what that feels like and seeing that it’s a dead end inside one’s heart even though we don’t see there’s no way out was kind of instructive. And I’m grateful for it. And I also wonder how we begin to tell that same story as well as find the human beings who finally lay down the arms and the guns. How do we tell the stories about the laying down of arms in the middle of greatest fear, facing one’s death, saying “I’m not going down the road of violence”, where does that take us? So this whole experience has sort of been nice into thinking more about those stories.

EJO: As a military leader, it was ridiculous that reconciliation was even anything inside of our memory that I had no way that I was ever gonna give up without dying. I’d rather die than to let it go. And it was really interesting because we fought all the way and we learned it the hard way, I was crushed by some of the things that I learned while I was, as an Admiral watching Laura, the President of the government, make the choices that she made. I was stunned. The first time we airlocked someone, I was like, “Well, that’s pretty cold.” And it was something that I really felt as Adama. That he was questioning. I mean, as far as I’m concerned, we blew it from the very beginning. We should have just stayed and fought and dealt with everybody else. We really lost out and I find that out in the last season. That’s when I finally confess that and I say, “I made the biggest mistake.” And she agrees. She says, “Yeah I think we blew it.” And we did in some ways, but in other ways, we would have never been able to survive as humanity without reconciliation. There was just no way. And, look it, I’m an atheist, as Adama, I’m an atheist, I don’t believe in God. Ever. Never did we believe in God. Are you kidding? Please! It’s just a matter of, “This is it. One track, one time. Wherever the flower goes, when it dies, that’s where I’ll go with it.”

And so it was really a very direct line to understanding what this war and this battle was. And then to see me get to the end, and just completely say, “Boy, are we lucky we didn’t do what I wanted to do?” It would have been stupid. And it would have been exactly, exactly what we’ve done to ourselves today. We’ve boxed ourselves into a hole. And I don’t know what’s gonna happen with North Korea, I don’t know what’s gonna happen with Pakistan. They all have nuclear weapons. There’s still I think three or four pieces of nuclear weaponry from the Soviet Union that is in briefcases that haven’t been located. I think that that’s a truth. I’ve heard that from many, many sources. The decimation of the Soviet Union. And if that be true, that where are they, what’s gonna happen? I mean, the fact that they didn’t drive the planes instead of going into the Twin Towers, if they had driven one of those planes into one of the nuclear power plants? I don’t know what would happen. I don’t know what to do. Could that have melted down—could it have been a China Syndrome? I don’t know. I used to know at one time. I remember during the ‘50s, when they told me that 19 consecutive hydrogen bombs activated at the exact same time would knock the planet off its axis. And they said, “Well, no one’s gonna let 19 bombs at the exact moment go off.”

GB: Not 20?

EJO: 19. They had it down. I remember, I said, “Right now, today, how many would it take to knock us off our axis?” From what I understand, the first strike syndrome is if you throw one, we’ll throw 20. I think that’s how it works, correct? I mean we knock it out, they throw one at us, we’re gonna throw 5 or 10 at them, nuclear warheads going after that one. And we’ll hit that one, but the other ones are going to hit somewhere. They’re gonna do something. They’re gonna blow up somewhere. And I think it’s gonna be a lot worse than we really anticipate, and we don’t want, none of us want that. So, my character only wanted to defend us in a war understanding. And that’s why I think the most critical scene was the scene where he says to Tigh, “We’re abandoning ship.” That was it. I mean, that cracked everybody. Everyone that knew this program knew it was over. It was over man. And you could sit there, and you could see Tigh just going, he was just crushed. It was over. We weren’t gonna have a battleship anymore. Who are we gonna fight, what are we gonna do? So we threw a war and nobody came. Oops.

But again, I really appreciate—I don’t know, I find it hard to understand the death penalty. Me personally, as a human being, okay? And yet I understand the Nuremberg Trials really well. I mean, [emulates a gun killing a Nazi soldier]. Just, yeah. Next. Ugh, next. And yet I can’t—how do you deal with that? What do you think of the honesty of saying to you, “OK. We get Bin Laden. What do you do with him?” Reconciliation time. Go, reconciliator.

GB: Wow.

[audience applause]

EJO: You tell me. Go.

CM: I work for an organization that opposes the death penalty. We are an organization that has held that over a period of many, many years, and has become increasingly prohibitionist. It’s based upon a common value that says that human life is sacred and if the solution to our problems is taking human life rather than restoring and defending human lives, then we’re definitely on the wrong track. So, we, after September 11th, were as horrified as the rest of you guys. We are based in New York, as you know. And the High Commissioner of Human Rights at the time said that what we had witnessed was a crime against humanity. Not just an ordinary act of war, or an ordinary crime, but a crime against humanity. The targeting of massive numbers absolutely. And the appropriate response to a crime against humanity is precisely to find the perpetrators and to bring them to justice. And there are justice systems internationally that have been effective in holding fair trials and bringing war criminals and horrific criminals of all sorts to justice without capital punishment. So there’s no doubt that you can have effective justice without capital punishment. We can be humane, that we don’t have to stoop to the levels of terrorists and war criminals and others in order to win the battle against them. To the contrary, you can get yourself caught up in an approach, where in the name of defending yourself from outside threats, as we saw in Battlestar Galactica, you contribute to the corrosion of your society from the inside. Then, what’s the point? What’s the point of the fight?

[Audience applause]

DE: On the other hand, if we had captured Osama bin Laden, I think there are a lot of us, even on the left side of the aisle, who would’ve loved to see that motherfucker airlocked.

[audience applause]

MM: It’s OK for him to use that word. I coined the phrase.

DE: You really did.

MM: He can use it whenever he wants.

GB: Steven?

SS: Yeah, I think also just to extend on the right side of the aisle, the politics of it. So you airlock Osama bin Laden. You get a thousand more Osama bin Ladens, and this is commonly known. You create another phenomenon. That’s what you’re doing in the end. I mean, you get some personal satisfaction, okay, what’s it worth? Is it worth the thousand other attacks that are going to be encouraged? And I think for those of you who heard President Obama’s speech today [to the Muslim world], it’s clear that there has to be a new approach. There’s some columnists that are calling it the mother of all reset buttons. There’s a new tone, and people can look at and address each other as peoples, nations looking at each other with respect. Because otherwise, I don’t think there’s much of a future.

GB: You know, I wanted to take a second and mention the Los Angeles Times is a part of this. I’m very happy to be here for the Times, and we’re very proud of our entertainment coverage, but a lot of the things that we’re talking about today, the Los Angeles Times has one of the greatest global reports, world news organizations in the world, and we have people, friends of mine, who are risking their lives all over the world, bringing us great news. People like Barbara Demick in North Korea and John Glionna in North Korea, Paul Watts in Iraq. We have people in Burma and I can’t tell you their names, because we don’t put bylines in the story to protect them. And I think that everybody up here would agree, and everybody probably in this room, the only way we can really find any sort of solutions or any progress within ourselves in a society this large is to be informed. And so I would encourage you to read the LA Times. I would ask you guys too—and the New York Times and everybody else—us mostly. And I don’t care if you read it, but buy it.

[audience applause]

[ScriptPhD special note—cannot agree with this more. A big thanks to all our venerable journalists risking their lives around the world to bring us news coverage. Please support your local newspaper.]

GB: What about people who love Battlestar Galactica, and have been energized by this conversation, tell us maybe down the panel, something people can do. Either something that they can actually go and do, maybe a book to read or a website to visit, or something to volunteer for, interact.

SS: Well there are no shortage of opportunities to volunteer for human rights. I mean, right here in the United States, there are a number of excellent organizations doing human rights work. One in every one of your local communities to be sure, not to mention some of the big ones like Amnesty International or Human Rights Watch who do fantastic work. I think the most important thing though is to find out what the heck is going on and the United Nations is a club of countries, of member-states, of governments, and I always thought that most people knew the positions that their own governments were taking around the world on human rights inside the United Nations. The compromises that are made, the disappointing declarations that come out of those exercises, you would be rather surprised. So whatever is your government, whatever your government representative, make your voice heard and tell them that you expect that your country will defend human rights, that it will respect human rights at home, that it will respect human rights abroad, and it will defend human rights in government organizations. So I think number one, finding out what’s going on is easy these days, to go on to the website, to get the human rights story of any of 192 countries. There are 192 countries in the UN, including yours, and every one of those countries violates human rights. Find out what they’re doing, make your voice heard, and demand that you want a law-based, respectful government that believes in accountability, that believes in accountability for perpetrators, redress for victims and that is not particularly favorable to things like waterboarding and airlocking. By the way, the UN would call airlocking extrajudicial, extralegal in summary executions. Try and put that on a T-shirt! This is why we need Battlestar Galactica!

CM: I would just say care. Care about one thing. Care about one issue deeply and act.

RDM: Yeah, I think you have to decide what matters in your life. I think you have to decide that it’s not just a theoretical idea, not just a political concept that you happen to agree with. I think you have to decide personally that this is something that matters to you, that you care about the world that you live in and that you decided that “This matters to me, and I as a human being want to help effect change in some way.” It matters who you throw your vote to, it matters who you throw your money to, it matters how you treat your neighbor, it matters how you check yourself out in the world, and I think if you make that kind of choice for yourself, however you express it and however you choose to act upon it, it goes towards the larger goal of helping to improve the world.

DE: I just think we have to find someone to beat the hell out of Glenn Beck. I mean, we all have friends who watch that shit. Bill O’Reilly. We’re all intelligent people here, we all read books, well with hard covers I guess, but I think we’re exiting the age of ignorance as a virtue. And entering a period of time where it’s OK to ask questions, it’s OK to be intellectual. It’s all right to be smart. And all I can say is tell a friend.

MM: On that note, look who I got stuck between. [laughter] No, I don’t really have anything to add, except that perhaps we can remind ourselves that being compassionately involved in life is more fun than being separate and defensive. That would make it an easier adjustment.

EJO: I’ll just end it by saying that everything everyone said about information is the key, but the problem is my son and daughter-in-law just got back from Turkey and they were watching CNN in Turkey. It’s a little bit of a different kind of news coverage in Turkey than it is in the United States and that really bothers me. That national BBC is kind of different in every country, it kind of goes with wherever you’re located. And that tells you an awful lot about what we’re receiving in this country. And it really hurts as soon as you realize, “You know what, it’s hard to get constant information, even from the LA Times.” Everybody has got a problem, because we are human, and we love to put in our own sense of being in everything that we touch. So we really have problems with that. So I say, like David said, “Tell a friend.” Because you really have to be careful. You are what you eat, you are what you think and you are what you do. That’s a given. Good luck.

[Brief clip of The Plan]

EJO: I couldn’t have imagined this kind of a situation happening at the end of this kind of a show, where you would actually start at the beginning, and it’s a masterful piece of understanding, Ron. I know that Jane Espenson and all the writers who thought this through—David, you guys—GENIUS. Because after you’ve seen The Plan, you’ll want to go back and see the whole series again.

GB: I’m gonna have to go back and buy it on DVD.

EJO: The difference between the show and the DVD you know. By the way, the DVD of this is coming out sometime in September, I think, in August, I don’t even know.

[Unknown person]: July.

EJO: You’re kidding?!

GB: The series is coming out in July. The Plan comes out in the Fall.

EJO: The Plan comes out in the fall. Big difference, if you haven’t seen it on DVD, it’s a big difference with what you saw on television. For instance, The Plan is 2:06 the way you’re gonna have it on the DVD. When you see it aired, it’s gonna be 88 minutes.

DE: Plus they’re all naked!

[laughter]

MM: They ARE all naked.

EJO: All I can tell ya is that it’s an extraordinary look at what the Cylons—how they masterminded what they did. And I have to tell you right now Dean Stockwell [Cylon Model 1] is a brilliant artist.

[applause]

EJO: Gotta really give him his due, because he does a magnificent job of completing The Plan. And I gotta tell ya, not to give anything away, it is exactly what you think it is. You see the complete opposite of the entire first 281 days of what we went through. Because they’re seen through the eyes of the Cylons. It is breathtaking. It’s fantastic, it’s not fun. But I will say that you will sit there going, “Oh my God.” But basically, you will go back and see everything when you go back and see the series then again, you’ll see it on DVD, you’ll see the extended versions of everything, correct? All the DVDs are extended. You’ll see, everything I directed, nothing was under 65 minutes.

[laughter]

EJO: Anyway, The Plan is exactly that. It was how they planned to do what they did and how it happened. And it was monumental. I have to ask Ron, did you enjoy it?

RDM: It was okay.

[laughter]

EJO: He’s drugged.

GB: Mary, you were introducing someone before the music came on.

MM: I was. Michael Reimer, where are you? Could you stand? Michael Nankin? Both of these directors were responsible for a great deal of the forward movement of the show and the articulation of these themes that we’re all talking about tonight. They came in with great understanding and talent and fearlessness, too, and brought these performances to the surface. Literally, brought us out. And I know that many of you in the fan bases are very aware of both of them. I don’t think Michael Reimer has ever been to one of these events, so we’re very thrilled to see him here.

[audience recognizes them]

GB: Now we are going to turn it over to you guys for some questions. There are people with microphones in either aisle. I would ask that you don’t make proposals, declarations of self, I ask that you don’t threaten, or pitch anything. Literally or figuratively. So if there is something that you would like to say that ends in a question mark, please go to the microphone.

Question #1: This is actually for the UN Gentlemen. There’s the ICC and the ICJ. Which one handles disputes between nations and could you give us a little background on what they’re both doing right now?

SS: Sure, the ICJ is the International Court of Justice, it’s also known as the World Court, and that’s the court that handles disputes between nations. The ICC is the International Criminal Court, which I think is one of the most important developments in recent history, that we managed to get an international criminal court. All these years after so may people campaigned to get one, since Nuremberg, that could deal with disputes around the world, individuals, criminally accountable under international criminal laws. So it deals with individuals, it’s distinct from the other. Both courts have wonderful websites, I see you’re online right now, so you can check that out to see what’s on the docket. Both of them have a very active caseload, the International Criminal Court, right now is engaged in cases from Darfur, cases Rwanda, and a number of other cases. But they have a political process.

CM: I just wanted to add that one can’t understate the impact of the ICC. Never did we think—I’m originally a Canadian diplomat, where we were pushing this forward, well it was being pushed forward for several decades—but when I was involved, did we think the impact would be as huge as it is. We now have people, militia leaders, rebel leaders, who are frightened of the ICC. So this is where you have a chain of accountability and accountability actually has impact. Joseph Coney is hanging out in the jungles of the DRC [Democratic Republic of Congo] and he’s afraid. He’s literally afraid because of all of the atrocities he’s committed, he will be pulled before the bench in The Hague. That is having an impact throughout Africa, and hopefully in 15-20 years, you’ll have people that will see that there is going to be accountability and there will possibly be an end to these horrendous atrocities.

GB: Let’s have some applause for that.

[audience applause]

Question #2: My question is for Ron. It’s basically, as you’ve said, you’ve tried not to make it too obvious what the headlines that you were trying to work into the specific political context of what you would show. I’m wondering if there was ever a time where you were inspired by something that maybe you wanted to work into the show but it either felt it didn’t quite work, there wasn’t a right place to put it, maybe it was a little too heavy, or just something that didn’t seem right.

RDM: I don’t know if there ever was. I’m trying to think. Were there things that sat on the writers’ boards? There was a guy who wanted to break something into the show and I can’t quite remember what it was—

DE: He wanted Mary to be bathing naked in the fountain.

MM: No, no, that was Eddie who wanted that.

RDM: The answer is yes, and unfortunately I can’t remember any specifics. But there were sort of various story ideas that were touted around here and there because we would realize that there were some things in the headlines that we could potentially use, or we could do a spin on a theme. And there were a couple of them that just sort of fell out over the course of time that we were never able to work in.

DE: Hollow did remain strange throughout the duration of the show.

[laughter]

GB: I want to know what happened to Boxey, okay [the young Season 1 stowaway who took a particular liking to Starbuck’s cigars only to disappear into the bowels of the Galactica].

RDM: Ohhh, that’s the next spin-off series.

Question #3: Years ago, my girlfriend, who is Chinese, had an abortion, it was my child and I never dealt with it until I saw your show. I really want to thank you for that. And it was rather unfortunate. Anyway, I was curious what the adaptation for China would be and how the show would have to change to be appropriate to that nation? Just wondering if it is illegally distributed or if there is a distribution. What have your thoughts been on that? [ScriptPhD note: Is it just me or was that first part the worst segue in audience question history??? Awk-WAAAAARD!]

RDM: I have no idea. That’s a really interesting question. I don’t know really what the status is of distribution to China in terms of—

EJO: It’s already there.

DE: Is it?

EJO: The internet.

RDM: I don’t really know what those issues are. I know that there are various issues in terms of censorship and government approval of the DVD, but I don’t know what NBC Universal’s deep deal is with that territory. If they have a deal, or if there is an issue that has popped up. But that is a very interesting question.

Question #4: My question is for Mr. Olmos. In the beginning, for your character, there is a speech that he gives, and he says that humanity never asked itself whether it deserved to survive. And I was wondering if you thought that question was answered by your character at the end of the series, and what you think of our humanity asking the same question.

EJO: That IS the question, isn’t it? Do we really deserve to be here? You ask the polar bear, and you ask the wolf, you ask the animals that are being decimated who really deserve to be here, if they’d answer in that way. I don’t know if they’d answer in the positive. I know that we have a hard time with it. In the show, I have a real hard time with it. And I don’t think I ever answered it. I think at the end, I just gave up. And I was very grateful that when Starbuck took us to this new place, and we landed there, whatever that was, mostly we look out the window and there’s this rock and it’s kind of looks like [unintelligible]. And only to find out that we didn’t get there, Laura and I never got there together. We got there, but as soon as we were there, she passed away. And so what happens to Adama? He ends up by himself. And in actuality we’ve taken it further because he built the log cabin. And then he went on to get a call—one day Tigh came up and knocked on the door and told him “We have a problem.” And we went off and solved it and found Lee, and he was in trouble.

[Audience laughs and applauds]

EJO: Wait til you see that! It’s coming up, and then watch out! But I don’t know, do we deserve—you tell me, do we deserve it. That’s the question. You ask yourself that. I think we do, because I really believe that we’re something that should understand ourselves and move forward and help. We’re here to help but a lot of us don’t understand that. If you can help, please do.

GB: You know when you were talking about the log cabin, it just occurred to me that Lorne Green went from Bonanza to Battlestar. You went the other way.

MM: I want to say something about the log cabin, which was mine. Just along the themes of sort of the ending. And the interesting thing. I am the only actress in the history of film or television to play a character who dies first and then gets married.

DE: It makes the wedding gifts so much easier.

[laughter]

DE: Until death do you…

Question #5: So we’ve been discussing a lot of things that are in today’s society and are around the world, but in the future, and this is more of a speculative question, if we get [artificial intelligence], will it necessarily be this conflict-driven AI that makes this television show so popular? And if it’s not, then what are we dealing with?

RDM: Well that’s the question that we all sort of face and we’ll probably face it sooner than we like to think about. It’s a classic trope of science fiction, machines rise up against us, it’s part of our story, it’s a part of other tales in this genre. And the more profound question may well be, what if they don’t rise up against us, but what if they’re just alive? And what do we do with that and what does that mean to us? What does it mean to look at something that may not have a bipedal form—if we don’t create robots that look like us, and you look at a blank wall of computers and somewhere within those hard drives is something that thinks, something that feels, and something that has all the definition of personhood, that you and I accept as being a person, what do we do with that? How do we feel about that? What does that do to our sense of identity and our sense of self in the universe? And I have no idea what the answer to that question is. But that question may well face us within our lifetimes. We could well deal with that situation at some point. And how we answer that question may be one of the defining moments of mankind. So I don’t know, but I sense that it leaves out there and waits for us.

Question #6: This question is for Mary. Laura Roslin, I think it can be argued, is probably one of the strongest characters on television in years—

[audience applause]

–and Battlestar is one of those weird shows that I find has a very large female audience. What’s it been like for you to—when Geena Davis made that joke when she won the Golden Globe, that little girl that looked up to her saying she wanted to be the President. So what’s it been like for you with the younger women in the audience and the genre being a little bit “We can do anything we want.” And Laura Roslin kind of helps us with that.