Dr. Mark Changizi, a cognitive science researcher, and professor at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, is one of the most exciting rising stars of science writing and the neurobiology of popular culture phenomena. His latest book, The Vision Revolution, expounds on the evolution and nuances of the human eye—a meticulously designed, highly precise technological marvel that allows us to have superhuman powers. You heard me right; superhuman! X-ray vision, color telepathy, spirit reading, and even seeing into the future. Dr. Changizi spoke about these ideas, and how they might be applied to everything from sports stars with great hand-eye coordination to modern reading and typeface design with us in ScriptPhD.com’s inaugural audio podcast. He also provides an exclusive teaser for his next book with a guest post on the surprising mindset that makes for creative people. Read Dr. Changizi’s guest post and listen to the podcast under the “continue reading” cut.

You are an idea-monger. Science, art, technology—it doesn’t matter which. What matters is that you’re all about the idea. You live for it. You’re the one who wakes your spouse at 3am to describe your new inspiration. You’re the person who suddenly veers the car to the shoulder to scribble some thoughts on the back of an unpaid parking ticket. You’re the one who, during your wedding speech, interrupts yourself to say, “Hey, I just thought of something neat.” You’re not merely interested in science, art or technology, you want to be part of the story of these broad communities. You don’t just want to read the book, you want to be in the book—not for the sake of celebrity, but for the sake of getting your idea out there. You enjoy these creative disciplines in the way pigs enjoy mud: so up close and personal that you are dripping with it, having become part of the mud itself.

Enthusiasm for ideas is what makes an idea-monger, but enthusiasm is not enough for success. What is the secret behind people who are proficient idea-mongers? What is behind the people who have a knack for putting forward ideas that become part of the story of science, art and technology? Here’s the answer many will give: genius. There are a select few who are born with a gift for generating brilliant ideas beyond the ken of the rest of us. The idea-monger might well check to see that he or she has the “genius” gene, and if not, set off to go monger something else.

Luckily, there’s more to having a successful creative life than hoping for the right DNA. In fact, DNA has nothing to do with it. “Genius” is a fiction. It is a throw-back to antiquity, where scientists of the day had the bad habit of “explaining” some phenomenon by labeling it as having some special essence. The idea of “the genius” is imbued with a special, almost magical quality. Great ideas just pop into the heads of geniuses in sudden eureka moments; geniuses make leaps that are unfathomable to us, and sometimes even to them; geniuses are qualitatively different; geniuses are special. While most people labeled as a genius are probably somewhat smart, most smart people don’t get labeled as geniuses.

I believe that it is because there are no geniuses, not, at least, in the qualitatively-special sense. Instead, what makes some people better at idea-mongering is their style, their philosophy, their manner of hunting ideas. Whereas good hunters of big game are simply called good hunters, good hunters of big ideas are called geniuses, but they only deserve the moniker “good idea-hunter.” If genius is not a prerequisite for good idea-hunting, then perhaps we can take courses in idea-hunting. And there would appear to be lots of skilled idea-hunters from whom we may learn.

There are, however, fewer skilled idea-hunters than there might at first seem. One must distinguish between the successful hunter, and the proficient hunter – between the one-time fisherman who accidentally bags a 200 lb fish, and the experienced fisherman who regularly comes home with a big one (even if not 200 lbs). Communities can be creative even when no individual member is a skilled idea-hunter. This is because communities are dynamic evolving environments, and with enough individuals, there will always be people who do generate fantastically successful ideas. There will always be successful idea-hunters within creative communities, even if these individuals are not skilled idea-hunters, i.e., even if they are unlikely to ever achieve the same caliber of idea again. One wants to learn to fish from the fisherman who repeatedly comes home with a big one; these multiple successful hunts are evidence that the fisherman is a skilled fish-hunter, not just a lucky tourist with a record catch.

And what is the key behind proficient idea-hunters? In a word: aloofness. Being aloof—from people, from money, from tools, and from oneself—endows one’s brain with amplified creativity. Being aloof turns an obsessive, conservative, social, scheming status-seeking brain into a bubbly, dynamic brain that resembles in many respects a creative community of individuals. Being a successful idea-hunter requires understanding the field (whether science, art or technology), but acquiring the skill of idea-hunting itself requires taking active measures to “break out” from the ape brains evolution gave us, by being aloof.

I’ll have more to say about this concept over the next year, as I have begun writing my fourth book, tentatively titled Aloof: How Not Giving a Damn Maximizes Your Creativity. (See here and here for other pieces of mine on this general topic.) In the meantime, given the wealth of creative ScriptPhD.com readers and contributors, I would be grateful for your ideas in the comment section about what makes a skilled idea-hunter. If a student asked you how to be creative, how would you respond?

Mark Changizi is an Assistant Professor of Cognitive Science at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in New York and the author of The Vision Revolution and The Brain From 25,000 Feet. More of Dr. Changizi’s writing can be found on his blog, Facebook Fan Page, and Twitter.

ScriptPhD.com was privileged to sit down with Dr. Changizi for a half-hour interview about the concepts behind his current book, The Vision Revolution, out in paperback June 10, the magic that is human ocular perception, and their applications in our modern world. Listen to the podcast below:

~*ScriptPhD*~

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology

in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development.

Follow us on Twitter and our Facebook fan page. Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

]]>

In 2006, The Discovery Channel, in partnership with the BBC, premiered the 11-part Planet Earth, the most expensive natural history mini-series ever filmed, and the first in high definition. It gave viewers a sweeping, intimate overview of the Earth’s diverse natural habitats. Yet long before Planet Earth premiered, plans were already underway for its follow-up opus, LIFE, which would focus on the animals, insects, and creatures that call those habitats home. The result, four years in the making, is historic television—never-before-recorded mating rituals, survival scenes, and brutal savagery. For the naturalist and the nature-lover, LIFE will, quite simply, change your view of life. After the “continue reading” cut, we preview the first few episodes and offer a rare candid interview with executive producer Mike Gunton. We are proud to make LIFE on Discovery Channel an official ScriptPhD.com Editor’s Selection.

The Earth is home to over 30 million diverse animal and plant species, each evolving, adapting, and surviving under rapidly changing conditions. The vast majority of these species has never before been documented in their native habitats… until now. The Discovery Channel and BBC have reprised their Planet Earth partnership, conducted over 3,000 hours of painstaking video footage, and endless hours of consultation with researchers and naturalists to create a living, breathing, not to mention gorgeous, catalogue of life as Darwin could only have been able to imagine it. Narrated by Oprah Winfrey, LIFE will be broken down into 11 episodes—the challenges of life, birds, creatures of the deep, fish, hunting mammals, insects, mammals, plants, primates and reptiles and amphibians, along with a “making of” episode—that will shed stunning light on the spectacular array of animal behavior, sometimes majestic (the penetrating gaze of Kenyan cheetahs ready for a hunt), other times flat-out bizarre (you haven’t lived life until you’ve seen a pebble toad bouncing like a taut ball down a precipitous mountain). “We wanted LIFE to represent the heartbeat of what John Hendricks thought about when he founded Discovery,” noted current president David Zaslav at a recent Los Angeles LIFE screening. “It shows you life as no one has seen it before, with most scenes recorded for the first time ever [on film or photography],” he added.

Indeed, LIFE showcases a number of television ‘firsts’—scientific and technical. Among other highlights, you will see the first footage of a spectacular humpback whale mating battle called the “heat run” (a truly mesmerizing piece of television!), killer whales stealing elephant seal calves, seduction of Vogelklop powerbirds and mating rituals of spider crabs, and my personal favorite, a Basilisk “Jesus” lizard walking on water! Take a look at a group of kimodo dragons hunting down a buffalo ten times their size in a highly calculated, precise (and vicious!) two-week attack:

In addition, LIFE producers and videographers developed a new camera tracking system—the “yogi cam”—to track migrating reindeer and elephants. Our interview below with executive producer Mike Gunton reveals more behind-the-scenes tricks and secrets of filming.

Take a look at this webisode that shows the innovative technology employed by producers and to capture some of the ‘firsts’ we’ve described:

Beyond the bravura filmmaking and technicolor high-definition images, what struck this scientist and film/television buff the most was that the personality of the animals shines through above all else. They are the real stars of LIFE. Sensitive moments of such remarkable intimacy evoke drama and suspense, relief and love. Yet midst these anthropomorphic tales, one is never led too far away from brutality and competition—the hallmarks, after all, of species survival. Scenes of lions attacking a hyena during the “Mammals” episode literally had me holding my breath, one that I was able to let go in relief as the hyena escaped surefire carnage. The dedication of parents in the wild is sometimes astonishing. A tiny frog the size of a postage stamp must swim miles against the ocean’s current every day to feed her young tadpoles an egg so that they can survive to independence. If you think human love affairs are full of spectacle, wait until you wade into the animal kingdom! There is nothing as pathetic as a lonely, rejected hippo doing the walk of shame across an arid desert and having to wait an entire year before he might seek companionship again. That same desert is home to scores of randy, chauvinistic male chameleons that are not very familiar with the concept of good old-fashioned romance; talk about wham, bam, thank you ma’am! And the primitive mating rituals of the violent, hyper-aggressive alpha male bullfrog are downright uncomfortable to watch. It is difficult to stare into the eyes of a young, intelligent Brazilian brown-tufted capuchin monkey figuring out how to use tools to crack open their beloved palm nuts and not see the face of a human toddler exploring their surroundings and gaining independence. It is difficult not to laugh at the naïve hubris of an ibex calf menacingly stomping its hooves at a predator fox whose capture it avoided by a hair’s breath and quite a bit of luck. And, after viewing LIFE, it is impossible to view animals of all size and shape as anything but breathtakingly complex and spellbindingly beautiful.

Interview with BBC Executive Producer Mike Gunton

Mike Gunton is the Creative Director of the Natural History Unit of the BBC, and oversaw production of LIFE. He has a first class degree in zoology and a doctorate from Bristol and Cambridge Universities.

ScriptPhD.com: Having now screened four episodes, and realized how grand and immense this project is, can you tell us about how the idea came about to do it?

Mike Gunton: It came about in about August of 2005, when we originally pitched [the project]. The team came together to properly begin work right at the beginning of 2006. Planet Earth hadn’t even aired; we had no idea how successful it was even going to be. The scope of Planet Earth, which was very much about the planet as a habitat and extraordinary landscapes and habitats of the world, and of course animals were in it, but they were animals within the landscape. And we felt it was kind of “the other side of the coin” to tell about that, which is about the lives of those animals and the struggles and challenges they face to survive in those habitats. So, we wondered if we could tell the complimentary side to the Planet Earth story—Planet Earth is the stage and LIFE is the play. That was broadly our thinking.

Also, of course, 2009 was the anniversary of the publication of The Origin of Species, so there was quite a lot of interest and focus on evolution and adaptation. And of course, LIFE is full of examples of extraordinary adaptation by animals, possessing adaptive “tricks”, whether physical or mental or behavioral, to overcome the challenges of survival. Then we realized that like Planet Earth, we had to be global, we had to go to every continent on the planet, and we also had to be completely broad-ranging in terms of the types of creatures and living things that we would feature to a much greater extent than we did on Planet Earth. We made sure that we’d cover everything from primates to insects and everything in-between.

SPhD: Just from the first few episodes, it seems the possibilities of choosing what animals to cover are infinite. So what ultimately dictated narrowing down exactly which species and scenarios you guys ultimately chose to capture?

MG: We decided there were, effectively, nine major groups of living things on the planet. We grouped all marine invertebrates together as a big catch-all of all creatures that life in the sea that aren’t fish. Then, to decide on the actual stories, that was probably one of the most daunting things of all, actually, to think, “There’s somewhere between 10 and 30 million species on the planet, how do we pick 150 that are going to be the most amazing, quintessential, rewarding representatives?” But we had a whole series of filters, and one of the main ones was that we did want to show people things they hadn’t seen before, things that would impress them and surprise them and show them how extraordinary animal behavior can be. Also, we wanted to show, rather than generic stories about lions or elephants or chimpanzees, very specific stories about individuals having individual challenges so that the audience sensed that when they’re watching, they’ve kind of been parachuted in on this particular animal’s life, on this critical day in its life.

SPhD: And it works quite spectacularly! I know we always want to anthropomorphize these creatures, but there was such personality that came out of some of the stories, like the poor hippo who couldn’t make his conquest, or the ibex out in Israel showing relief at outrunning the fox. So there was a lot of character that came out.

MG: See, I think this is really, really important, because anthropomorphism has a bad reputation. But I don’t think that what we’re doing is anthropomorphizing in the sense that people think it’s wrong, but actually people are frightened to accept that we’re all animals, [with] an integral spectrum of things that go on. And I think you can absolutely connect and relate to those animals without necessarily having to stretch to say these animals feel fear or concern or heroism or dedication, all those things that we admire in humans and ourselves. I think they’re absolutely there to be admired in animals. That’s something I feel very strongly myself, that there is a tendency to not think of animals as anything but little black boxes, when they clearly are not.

SPhD: Can you let us in on some of the secrets of what it took to capture these unlikely (and sometimes spectacular!) scenarios? Was it just patience, longevity, luck…

MG: All of those things, of course. I like to think we make our own luck. But luck is a big part of it. You do have to get lucky. First of all, we do an enormous amount of research, and we are drawing on a network or web of extraordinary experience. One of the things about people who work in the natural history industry is that once you join you never leave! So there are people who have worked in that place for thirty years, and the cameramen are the same. They have so much knowledge and experience that you start to “know” what’s likely to happen. And the cameramen tend to be brilliant naturalists. They have a real sixth sense about animal behavior and animal activities. So all of these things poured into the pot together, and stirred, does give you the chance to get things that you’d otherwise think to yourself are impossible. I often think to myself when I get back from a shoot, “How on Earth did we actually get that?” If you walk out into the Indonesian rain forest and hear a gibbon call, and it’s a mile away, how on Earth are you going to get anything more than a shot of that? And of course, we don’t do shots anymore—these are really complex, developed cinematic sequences. So the only way you can do that is by learning all the things in your favor: lots of periods of time, lots of science, we work a lot with the scientists. A lot of these stories actually come from them, because many of them are so new that you can’t get them in the textbooks or on the internet.

Watch a brief behind-the-scenes video that reveals some of the secrets of creating the series:

SPhD: Any precipitous moments for the crew? Anyone feel their life was in danger at any point?

MG: One of the things that we do is, we like to think that we are very safe. Knowing the animals, you don’t put yourself into situations where you are at risk. It’s very unlikely that anyone is going to get eaten by a lion, because we just know how it behaves in that way. Things where it got trickier, for example, are those komodo dragon sequences [in Episode 2]. Kevin, the cameraman, never felt particularly at risk, but he said it was unnerving because both creatures were so otherworldly. He has filmed reptiles and amphibians for 25 years, he said that once they’d made that first bite [into the buffalo that they’d end up excoriating], he felt they were like heat-seeking missiles. They weren’t going to be detracted from their mission, which was to track that prey for the next two and a half weeks. So although being amongst them was incredibly intimidating, he still felt that it was probably OK. Generally, when we film hunts, it’s over in a second. This was a kill that lasted two and a half weeks!

SPhD: Have any fun field stories to share with us?

MG: Just more along the theme of stuff that’s challenging or dangerous. One of the stories that we did that I think is probably one of the most courageous, certainly logistically the toughest, and most expensive, was we filmed a thing called a heat run, which is in the mammals program. It’s basically a humpback whale mating or courtship ritual. Effectively what happens is that a female, when she comes into season, will attract the males by various means—she whacks her pectoral fins and she bellows—and the males are then attracted to her. And once they get close to her, rather than allowing them to court her or to mate with her, she then swims off, and then effectively induces them to chase after her. While they’re doing that, they’re then in a fight with each other, and they’re all scrapping to see if they can be the one to eventually swim alongside her and be accepted to be the one to mate. These males get more and more hyped up and they start crashing into each other and push each other down and they blow these amazing bubbles out of their blowholes, and they come leaping out of the water and crashing down. And they’re swimming at seven or eight miles and hour. They get like a rocket.

To film them was incredibly challenging. We filmed them from the air, which meant that we had to have a helicopter. Now, this is the middle of the ocean, so we had to get the helicopter from Fiji and it was right at the end of its range. Filming from the boat itself was quite tricky, just to be able to keep up with them. But the most challenging and the most tricky thing of all was actually getting the underwater shots. Because the cameraman that did this couldn’t use scuba gear, the bubbles emitted from which would upset and disturb the whales. He had to do it on a snorkel. Then he had to take a single breath. So when these whales were hammering along, we had to get him in the boat, get ahead of them, plop in the water, take a breath, dive down, get some shots, come to the surface, take a breath, and so on about four or five times. He said it was like standing on a freeway with six juggernauts, six huge Mac trucks hammering towards him, with the drivers all having their eyes shut all while he’s having to hold his breath. We were in the water about 17 days, and in the end, it all boiled down to about a couple of hours.

SPhD: Given everything you’ve discussed, for people reading this before they’ve watched the mini-series, what would you guys collectively like the audience to get out of this? What are some of the things you hope that all this effort that went into this mini-series rewards them with?

MG: On two levels. As a television series, I want them to come away with thinking they’ve been immersed in the life of these animals, that the way we’ve done this, and the effort we’ve taken places them into the intimacies of these animals’ lives. And especially with the way that we’ve filmed it, so that you get the drama and the pace of and the excitement of the animals come through. And the other thing is, on a more philosophical level, I would hope that [the viewers] would take away, as I do, that the things that we admire in people can also be seen in animals. And that they are passionate, that they are concerned, they are wonderful, caring, sharing, powerful, aggressive, but they are individuals who have these unique characteristics. As a final though, people have asked me what I thought about LIFE, I can think of one word. Heroism. They are heroic. A lot of the animals do things that genuinely make the hairs on the back of your neck stand up in admiration of their heroic endeavors to survive.

LIFE premieres on the Discovery Channel Sunday, March 21st, 2010 at 8 PM ET/PT.

Enjoy more interactive content, including series photography, webisodes, a global map of endangered species, and and interactive “gene machine” to show relatedness of animals on the LIFE website. You can also follow LIFE on Facebook and Twitter.

View series trailer here:

~*ScriptPhD*~

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development.

Follow us on Twitter and our Facebook fan page. Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

]]>There is grandeur in this view of life, with its several powers, having been originally breathed into a few forms or into one; and that, whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved.

Charles Darwin’s postscript to perhaps the greatest work of biology ever recorded, The Origin of Species, ignited an acrimonious debate about science, religion, the mutual exclusivity thereof, and where we come from. 150 years later, as we celebrate the anniversary of Darwin’s monumental scientific achievement, it is a debate that has yet to abate. Regardless

of what stance one takes on evolution and natural selection, fascination with the life and times of this inimitable figure is undeniable. A new biopic, Creation, delves into the dichotomy of Darwin the naturalist and family man, the disapproval he faced from a devotedly Christian wife, and the inner anguish he faced in whether to publish his findings. ScriptPhD.com’s Stephen Compson was recently treated to a private screening of the film and had the extraordinary opportunity to sit down with Darwin’s great-great-grandson Randal Keynes, whose Charles Darwin biography the movie was based on. For our exclusive content, please click “continue reading.”

REVIEW: Creation

ScriptPhD.com Grade: A-

Creation tells the biographical story of Charles Darwin struggling to complete his opus: On the Origin of Species. The screenplay was adapted from Darwin’s great-great grandson Randal Keynes’s book Annie’s Box. Paul Bettany stars as the father of evolution, with his real-life spouse Jennifer Connelly portraying the devoutly religious Emma Darwin. Creation is not the story you think it is, especially if you’re of a mind to burn books along with anyone who tries to rub your nose in empirical evidence. This Darwin is immediately likeable and sympathetic because he’s tortured by his findings. While his persecuted-scientist friends urge him to publish and show that lousy church once and for all, Charles must first deal with a domestic dispute two decades in the making and lay to rest a daughter (Annie) whose death he blames on himself.

The opening is a series of coalescent images: particles in space gaining gravitational momentum transitioning to cells colliding under a microscope, becoming fish swimming together in a bait ball. As we move up the food chain, it’s immediately apparent that there’s a capable hand guiding the lens. This is director Jon Amiel’s most visually stunning work to date, and its vibrancy contrasts with the somewhat cold Victorian setting to give us a front seat in Darwin’s inner eye. The story jumps about in time and setting. Annie’s ghost haunts Darwin through the draft like an editor with a PhD. He tells of his Galápagos adventures as bedtime stories to his children, but it’s clear even to his youngest that Charles favors Annie over her siblings. His guilt is immense, as though by articulating the principle of natural selection he has allowed his favorite child to succumb to it. And so the scientist is forced to confront in the most painful way possible the cold ramifications of his findings. Only by laying Annie to rest and reuniting with his religious wife can he publish his findings. This is thematic film-making at its best, the centuries-old debate over Darwin’s findings personified by immediately human performances.

There’s another layer to this story about science and religion. Darwin argues with his wife about the superiority of science while ingesting doctor-prescribed laudanum for an upset stomach. Laudanum is a powerful opiate that also influenced the works of Lewis Carroll and Samuel Taylor Coleridge (we must imagine briefly the time when critics will look back at our generation and think to themselves, sweet Darwin, they all drank so much coffee). Also, both Charles and his daughter are treated for illness by having torrents of cold water poured onto them, as this was supposed to be the cutting edge of medical science. Here is one of history’s most respected scientists giving and receiving treatments that must have been detrimental at best. It is an interesting and subtle note: that science is not always so objective, that both doctors and ministers haven’t yet had their last word, and the only ones we can be sure are wrong are the polemicists.

The official studio notes describe the film as “Part psychological thriller and part heart-wrenching love story,” which is a typically superfluous press packet way of saying it’s a drama. You wouldn’t expect a scientist’s biopic to be filled with such vibrant themes and images, or noteworthy performances, but Creation has both. Jennifer Connelly’s spoken pieces are heart-wrenching, but she is at her most violent when she sits in front of the piano, damning her husband with every note like Madame Defarge knitting a guillotine roll-call. Though the high drama occasionally stretches dangerously thin, the married stars bring a natural chemistry that keeps the dough from tearing.

Creation is a quiet film released on the year marking the bicentennial of Darwin’s birth and the 150th anniversary of his seminal work. Rarely does a film confront controversy with so balanced and nuanced an account. Both sides will find their talking points, but the characters are so rich you might just forget about keeping score. Yes, it’s a story about a scientist, but it’s a lot better as a story about a man struggling to tell right from wrong and keep his family together. Then at the end—Spoiler Alert!—this man just happens to publish the theory of evolution.

Exclusive ScriptPhD.com Interview With Randal Keynes:

Randal Keynes is the great-great grandson of Charles Darwin and author of the biography Creation: Darwin, His Daughter, and Human Evolution, on which the movie is based. When I arrived at his hotel, I was informed that the interview had to be postponed for an hour because Mr. Keynes was at a Twitter party. I must confess that I’ve fallen behind in my grasp of Twitter-speak, but it sounded to me like I was waiting while he sat upstairs in his underwear updating his feed. During the interview, I would often catch Mr. Keynes staring lewdly at the overgrowth of hair sprouting out the top of my shirt, and when I asked him to focus he sipped deeply from his red wine and went back to tweeting. I’m kidding about the chest hair. But not the Twitter party.

ScriptPhD.com: Tell us how you found the item that inspired this book about Darwin, his daughter Annie’s writing box.

Randal Keynes: For most of my life I took very little interest in Darwin, but about ten years ago I was asked if I could help the organization that opens the [Darwin] house to the public. They wanted information about how Darwin lived with his family. My father had inherited a big chest of drawers from his mother, Darwin’s granddaughter, and in the bottom corner of this chest I found this writing case, and in it there was a folded piece of paper with Darwin’s handwriting: “Annie’s illness.” It seemed to be a note that he had made of the treatments he gave her every morning and how she reacted to it.

SPhD: So he was actually treating his daughter himself?

RK: And this was the extraordinary point. It didn’t fit with my idea of the great scientist on his pinnacle. I found a character that was clearly the real Darwin, because he and his wife Emma were so devoted to Annie: she helped the two of them, keeping them cheerful, helping Darwin with his science. So her father, distressed as he was with all the difficulties of his theory, had to come to terms with her death as well. I found that much of his thinking about human nature one could link with his experience, his love for his wife, the pain of Annie’s illness, his desperation to keep her alive, his sense of emptiness when she died, and coming to terms with the memory. That offered a view of Darwin that was very different. People usually think of tooth and claw, the struggle for existence, life without purpose. I discovered a more human Darwin.

SPhD: What surprised you the most about him?

RK: Especially that, but let me think of something else. I was surprised by the stress and worry he experienced as he worked out the theory and saw how many people would want to attack it when he gave it to the world, and that comes out in the film.

SPhD: What do you think of the film?

RK: I think it’s wonderful. I’m so pleased that [director] Jon Amiel and [screenwriter] Jon Collee were able to shape the story the way they did, and get Paul Bettany and Jennifer Connelly, wonderful actors. In particular, I am particularly pleased about the way they linked Darwin’s interactions with Annie as an infant to those with Jenny the Orang[utan]. Paul Bettany was able to relate to the infant, and to the orang, just as Darwin did. He was just following Darwin. He wasn’t acting, he was just [being] a sensitive, engaged human.

SPhD: What was the importance of [Darwin’s orangutan] Jenny?

RK: Very few people paid attention to her until I found this comparison with Annie. This picture was in the British Library. The strange thing about Jenny was everyone went to the zoo to see her, because no-one had ever seen such a human creature. They hadn’t seen the great apes, they hadn’t seen chimpanzees, they just didn’t know they existed. Almost everybody found it distasteful. The young Queen Victoria came to the zoo to see this big sensation, and she went back to Buckingham Palace and wrote in her diary: “How painfully, and disagreeably, human.” So the young Darwin saw her, and while everybody else was pained, he saw her and he loved the link that he saw.

SPhD: Why do you think we’re still arguing about evolution?

RK: Because the point about our common nature with animals is so challenging and so unwelcome to people who want to think we’re special, we have special favor given by our maker and all that. I think that’s the crux, it’s our thinking about ourselves. I don’t really believe it’s a worry about the literal truth in the book of Genesis. Many many Christians have no trouble reconciling the biblical account of creation with the Darwinian one. Why people were upset by the Origin, I think, is mainly because it suggested to us that we have a common nature with animals. Darwin wrote a second book called The Descent of Man. In his first book On the Origins of Species he said nothing about human evolution, even though there was a clear indication of it, and didn’t publish the second until ten years later, after people had come to see the value of his idea.

SPhD: What did you find you personally related to about Darwin?

RK: I related to his passion about his theory, and his worries about it. If I had the extraordinary fortune to have his idea, and have the responsibility of offering it to everyone else, knowing the response I’d get, I can see how I’d be terrified by it, as he was. I admire him for his bravery.

SPhD: Describe Darwin’s relationship with his deeply religious wife Emma.

RK: He loved her deeply. He wanted to give her all the support and everything that he could. The relationship was for periods of their lives very difficult, because they couldn’t find common ground on these issues of faith and truth: her Christian faith, his scientific truth. But she kept him alive, he was very ill for most of his life with the stress. She protected him from people like Hooker and Huxley who wanted him to reveal his theory. She made this great sacrifice, because he meant more to her than anyone else, and that’s the truth of it. It was a wonderful story, how they found each other, how they loved each other, how she supported him, and how grateful he was to her.

SPhD: What do you think ultimately compelled him to publish? The film touches on a few different moments, but what put him over the edge?

RK: He thought it was profoundly important that people should realize where we came from, how we were part of natural life. He was also very ambitious. He saw the extraordinary power of the idea. People have said it’s unique in how such a simple insight explains so much. Evolution by natural selection explains, not just the origin of life, but the development of it as well. He wanted the pride and the pleasure of giving it to the world, and the delay was just the other side of the coin, I’m gonna say flack. If it stands up, eventually, it’ll all be praise. It’s still not all praise.

SPhD: If Darwin could be any animal, what would he be?

RK: I think he’d love to be a moth, feeding on beautiful plants with his tongue. Taking the pollen from them and putting it into another plant and enabling them to evolve. That was one of the processes he thought was miraculous.

SPhD: How about you?

RK: I’d like to be a condor.

SPhD: You fancy yourself a carrion feeder?

RK: Oh yes. Well, when [John James] Audubon first met the condors he wondered how on earth they found the carrion, the corpses that they lived on, while they were high up in the Andes. He wondered, could they be smelling at that distance, or could they possibly be seeing it? So he took a group of Turkey Buzzards and put some flesh in a paper bag, so you could smell it, and drove it past a group of Turkey Buzzards: no reaction. Then he took the corpse out of the bag, immediate excitement. So when Darwin got to the Andes, he repeated Audubon’s experiment with real condors, and it was clearly sight for them too. I just loved that.

SPhD: Your Wikipedia entry describes you as a conservationist. What are you interested in conserving?

RK: I’m going to change my answer to that last question. I would like to be a giant tortoise on Galapagos, because they have wonderful food—

SPhD: –No corpses?

RK: –Right, and they eat it in total safety, and have a very restful and pleasant life on beautiful islands. They are under such threat, because everybody wants to go see them and when you bring humans to an ocean archipelago they bring diseases and other impacts. I think Galapagos is a treasure for humanity, it shows us what Darwin saw, and shows us how the animals and plants have evolved.

SPhD: Would Darwin support Conan O’Brian or Jay Leno?

RK: Ah, I know something’s going on, is it competition for their timeslots? Is Jay more pugnacious then? I think I know Jay Leno, I don’t know Conan, so, survival of the fittest eh?

SPhD: Ruthless.

RK: But you asked who Darwin would support. He recognized that the fittest survive, but he always had a sympathy for the losers. Don’t say loser. The underdog. Darwin’s for Conan.

Stephen Compson studied English and Physics at Pomona College. He writes fiction and screenplays and is currently working toward a Master of Fine Arts at UCLA’s School of Theater, Film & Television.

~*Stephen Compson*~

***********************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development.

Follow us on Twitter and our Facebook fan page. Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

]]>

The Human Spark is a new three-part documentary special on PBS in which Alan Alda soldiers after the genetic and cognitive elements that make him smarter than your average chimpanzee. In the first episode, he travels to numerous archaeological sites and many of the world’s finest research centers to look at how humans diverged from neanderthals and why we’re the ones writing the history books. Episode two tracks a series of experiments on chimpanzees and human children to illustrate the psychological differences. The final installment shows off some of the latest brain imaging studies and and linguistics research to postulate a theory on the nature of the ‘human spark’. With an interesting scientific premise as a basis, a hot field in which a lot of exciting, new information has been discovered within the last decade, and financial sponsorship by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, one of the most generous and prestigious in all of science, this should have been a knockout for PBS. Sadly, the finished product is merely another example of a strong concept with poor execution, punctuated by bloopers that the documentary’s creators were too pressed for content to take out.

REVIEW: The Human Spark (PBS)

ScriptPhD.com Grade: D

The Human Spark‘s one saving grace is that the first episode is filmed primarily inside the lab, showed the scientists working on fossils, and actually spotlighted some of the technology and methodologies that are making the current discoveries possible. Learning about how scientists date teeth was a pleasure compared with the rest of the program. Alda’s awkwardness as host is at times endearing but too often tedious. His voice-over work is fantastic, but when it comes to live action this scripted special feels a little too real. When the grad students sit down for lunch at the archeological site, Alan finally gets to vent what’s been on his mind since M.A.S.H. wrapped:

“Here’s what I don’t get. The people who moved out of Africa, and who we came to call the Neanderthals, who got here, and didn’t change much from the time they got here until the time they died out, although that was a long period of time, they survived but they didn’t change. They—they’re—their—they came from the same people we came from, and some- and then at some point we started changing. We started being able to change. And then we came up here. These two groups meet. Why did—having come from the same background—why were we able to change and they weren’t?”

On the plus side, after he got done asking this question, the filmmakers only had 50 more minutes of that hour left to fill. And you know they had smart scientists on the show, because one actually provided a cogent answer. Here’s what really kills the premise with this program—PBS did a lousy job editing because they had nothing better to show us. That’s the only justification for content like this. Alan was sent to six different countries to visit archaeological sites that all look the same anyway, so it’s hard to believe they couldn’t afford to do another take on that burning question of his. And as for the visuals, this filmmaker was thoroughly offended (more on this in a minute). The entirety of the show, experts throw huge abstract numbers at the audience: this skull is fifty thousand years old; this bead is over a hundred twenty thousand years old; here’s an imitation sea-shell from two hundred thousand years ago. It’s easier to read them here on the page, but that’s my point. Would it have killed them to put a lousy timeline up on the screen for 10 seconds? The only visual they could afford was a pirated Google Earth frame to show us where the neanderthals camped out. They had imitation sea-shells at that campfire. We just don’t know when.

In case you risk watching this travesty and twenty minutes in you choke on your own boredom, let ScriptPhD.com fill you in on what you missed during the last half hour: Alda shoots primitive projectile weapons at a plastic reindeer. (Yes, PBS members, your money is being well-spent!) The production crew craft an authentic stone-age spear, but instead of throwing it like our humanoid ancestors, Alda’s cheating with a fancy spear-thrower. And he still can’t hit a stationary Christmas decoration! After ten minutes of hopeful attempts ending in bitter disappointment comes the best part: he purportedly hits the thing, but we miss it because the camera’s zoomed in on his face, then it pans over to where someone obviously stuck a spear into the deer’s behind. With effects like that, who needs James Cameron?

Episode Two is an examination of what separates us from chimpanzees, our closest genetic relative. The second installment demonstrates even more clearly that poor presentation can be the death of good content. We’re greeted in this episode by Alda sitting between a chimp and a human child. As he clumsily reads the opening statement from the teleprompter, the kid jumps in with an answer to one of the rhetorical questions, but Alan just talks over him. No one thought that was worth a second take, but this time I think I know why. Across the table from that outspoken little boy was a menacing ball of barely-contained bloodlust. Apart from some developmental psychology, you will learn one important thing from this episode: chimpanzees hate Alan Alda. I’m talking about Hondo, The Human Spark’s sympathetic antagonist. Hondo is a male chimpanzee with an unfortunate childhood that would make Jane Goodall cry: stripped from his family at a young age, denied the furry harem that was his genetic birthright. Day after day, he endures the seemingly trivial experiments of his human captors, given a 50% chance at extracting a measly grape for his efforts. The biologist who describes his characteristics may or may not have finished puberty, his voice cracking with glee as he and Alda share some ground-breaking connection between monkey and car salesman. Does it surprise any of us 99 percenters that Hondo risks it all for one noble shot at wiping that disoriented grin off the aging star’s face? As our host and his eager partner-in-science engage in yet another conversation that didn’t need to be televised for a viewing public, I found myself rooting for Hondo as he hurls himself against the protective glass, proving that even though he can’t best a three year old at logic puzzles, this chimp knows a thing or two about the human spark.

And who can blame Hondo’s aggression, with a format born of the logic that to educate does not mean to entertain. “You’re getting it all wrong!” his expression screams as he fails another test to determine whether he can understand the concept of weight, and throws himself in frustration at the bars between him and his inquisitors. In all seriousness, the presentation does a huge disservice to the undeniable brilliance of the researchers introduced during this segment, particularly since PBS’s mantra is to educate through entertainment. These scientists are people who’ve devoted their entire professional lives to studying what it means to be human, people who conduct seemingly cutting-edge research, yet the program feels like a perfunctory grade-school field trip. How is it even possible to capture monkeys on camera for any extended period of time without it being entertaining? Episode 2 is a point-counterpoint competition between children and chimpanzees that showcases the somewhat mundane scientific method (performing test after test to discover the key differences in psychology). Although these tests illustrate the evidence, the conclusions drawn from them are much more exciting than the process.

The research hints at powerful revelations: the way human children are programmed to teach and learn may give us an evolutionary leg up. But even here, one is left with a lingering doubt: what if the human subjects are more teachable because they’re all children? The Human Spark would have us believe that the kid wins out because the adult chimpanzee would rather pursue the grape with his own strategy, ignoring the researcher’s demonstration. But don’t we afford the human adult the same courtesy, to ignore all rational advice and pleading, just go out and buy the boat, marry the fifth wife? My decidedly human confidence is not bolstered when, after being shown a box with both sliding and pull-out doors to reach the same grape, Alan can’t figure out how to get the darn thing open, either.

Shocking as it might be to believe, the final round of this documentary is the most exasperating. For one thing, it’s the most self-indulgent. As the camera rolls, Alda volunteers himself to the latest and greatest in brain imaging techniques, and some nervous tech compliments him on how bereft of open space his skull cavity remains. After some painful filler including re-used footage from the previous two episodes, we get to watch as different spots on his brain light up in correspondence with different actions. To reiterate, interesting conclusions masked by poor presentation. Nothing envelops an evening with a drowsy warmth like linguistics. At one point, it seems we are to believe that grammar is the root of the human spark. In as much time as it takes to start denying that to yourself, we’ve moved on to religion, coupled with a cheesy montage of people presumably…being religious. And then, like that poor chimpanzee on a crash course for Alda’s head, a relatively startling and profound conclusion: mankind’s ability to think and strategize about the future sets him apart, and one of these brains can (almost) prove it.

Film is a visual medium. Hearing scientists explain their research is one thing, but forcing us to watch them do it rather than illustrating the concepts is uncreative and lazy. Brilliant as they are, rarely would one of them dare to send an unedited, offhand remark out to their colleagues for peer-review, so why is this acceptable for public consumption? It’s just bad television. So is the lack of adequate visuals that even daytime cable programming can muster and the poor editing that accompanied this performance. Some of the backgrounds looked like they were slapped together from iMovie, which is a fine rudimentary program when you’re putting together your baby’s first steps to show grandma. Finally, economy. If running a dramatic series for twelve episodes throughout the season, maybe you might show some flashbacks during the finale to remind viewers of key plot points. But a three-part science special doesn’t need to be recycling footage from the first two to fill its third episode. There were about forty minutes of good material that were made to last three hours. Leaving in bad takes and long-winded responses to fill that time is an insult to the PBS audience’s attention span. Programs like this make up the nerdy half of the void that inspires blogs like this one. On the other side, you’ve got entertainers making a mockery of the realities of science, and before you lie the fruits of educators using a bludgeon where a crime-scene investigation would have done nicely.

Trailer:

The Human Spark premieres January 6, 13, and 20, 2010 at 8pm on PBS (check local listings).

Stephen Compson studied English and Physics at Pomona College. He writes fiction and screenplays and is currently working toward a Master of Fine Arts at UCLA’s School of Theater, Film & Television.

~*Stephen Compson*~

***********************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and pop culture. Follow us on Twitter and our Facebook fan page. Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

Music. We all know what it sounds like when we hear it. It has the ability to create powerful emotions, or bring back memories from the distant past in our lives. We may use it when we exercise, study for exams, read, or for traveling form point A to point B. But what is music? Is it unique to human beings? How do we interpret music when we hear it? Are the emotions created by music universal, irrespective of the listener’s culture and country of origin? Can music teach us anything about how the human brain functions? These interesting questions and more are explored in the fascinating documentary The Music Instinct: Science and Song, a PBS production that was recently honored with the top prize at the prestigious annual Pariscience International Science Film Festival. ScriptPhD.com’s newest regular contributor NeuroScribe provides his review and discussion under the “continue reading” jump.

REVIEW: The Music Instinct: Science and Song

ScriptPhD.com Grade: A+

In his stirring and enormously popular 2007 opus Musicophilia: Tales of Music and the Brain, neurology professor Oliver Sacks examines the extreme effects of music on the human brain and how lives can be utterly transformed by the simplest of harmonies. These very themes are the foundation of The Music Instinct, hosted by Dr. Daniel Levitin, a neuroscientist and author of This Is Your Brain on Music: The Science of a Human Obsession, and 10-time Grammy award winning musician and vocalist Bobby McFerrin. Together they bridge the gap between listening to and creating music with neuroscientists seeking a greater understanding of how the brain works.

Dr. Levitin states in the program, “The brain is teaching us about music and music is teaching us about the brain.” Well, how does this happen? Music is after all information which the brain processes. How the brain processes and stores information is a huge area of basic neuroscience study. These studies are typically funded by the National Institutes of Health in Washington, DC. The results of these studies lead to improved treatment of patients suffering from a variety of human diseases. The incredible impact music has on people is remarkable. For example, the program mentions how music is used in hospitals to steady the breathing of premature babies, and the heart rate of cardiac patients. A three-year study from 2002-2005 on music therapy for infants was named by The Council for the Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences as one of 12 exemplar studies for the year 2006. For more videos and information on the power of music therapy, please visit the official American Music Therapy Association website.

Is music built into who we are as people? Some scientists do not think so, yet many others believe it is. What is music and how do we hear it? A basic definition would be that music is the vibration of molecules in the air which have a certain pitch and rhythm. These vibrations enter the ear and cause your ear drum to vibrate. As your ear drum vibrates, this causes the movement of three small bones called ossicles. These bones transmit the vibration to the nerves in the inner ear. It is here where the vibrations (initially music) are transmitted into nerve signals sent directly to your brain to be processed. In a nutshell, that is how we hear. While this is well known information, what isn’t well known is how and why music generates emotional changes in the brain after it has been physically interpreted. Scientific research is attempting to answer these and many other questions.

Scientists know a developing fetus begins hearing at seventeen to nineteen weeks of development. Can the fetus hear music? Does the fetus respond to music? The program shows a pregnant mother listening to music while the fetus’s heart rate is monitored. Researchers found that when music was played, the fetus’s heart rate increased. The heart rate of a person is one indicator of what is known as the “startle response”. The startle response is that “fight or flight” instinctual reflex the brain carries out to ensure an animal’s survival. This response is generated from very primitive areas of the brain. They also implanted a miniature hydrophone inside the mother’s womb to see if there was any natural sound in the womb. In addition, the hydrophone recorded what the music would sound like to the fetus. An audio recording from inside the mother transmits the pulsing of blood from the uterine artery. One can also hear the music as well fairly clearly as the infant would hear it—like a muffled sound as if you were underwater in the ocean or a pool. Many scientists think we are “wired” and listening to rhythm, the essential difference between sound and music, even before we are born.

The program also goes beyond just examining the cellular and physiological responses to music to discuss the differences and universal similarities of people’s emotional responses to music. In an interesting study looking at the emotions generated by music, participants listened to different types of classical music while various biological indicators of emotion changes were recorded. The neuroscientists observed when people listened to lighthearted sounds, the body was at a resting state. However, when they heard deep sounds say from a piano, heart rates increased and people began to sweat, indicators of stress. A very interesting recent study asked the question: Are there things about music which go beyond culture. Read about it here. A group of scientists, led by Dr. Thomas Fritz, traveled to the country of Cameroon in Africa. They visited a very remote group of people, the Malfa, living in the mountains. These people have never been exposed to Western music. In fact, in their language they don’t even have a word for music, yet they make musical instruments and play them daily. They were asked to listen to different pieces of Western classical music, and then point to one of 3 faces in a book. Each face represented a different emotion: happy, sad, or scary. The participants knew which emotion went to which face for the experiment. The scientists found despite these people never having heard Western music, they were able to identify music as happy, sad or scary, just as Western people could. Their conclusion was the emotional content of music is inherent in music itself, and is not solely the result of cultural imprinting. This study tells us there are some things about music and emotion which may indeed be universal, and not bounded by country or culture.

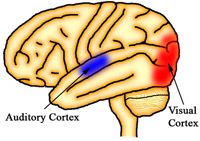

Nevertheless, our responses to music are not always universal. In Western cultures, a certain type of pitch is typically identified as being “sad”, yet the same pitch in a different culture is identified as being “happy”. This tells us there are some outside factors, such as culture, which help shape a person’s emotional response to music. Indeed, some of this behavior is in fact learned. Did you ever notice when you hear some music, without even thinking, you start moving your head, or tapping your feet? Why do we do that? Well, the answers aren’t entirely known. However, it is no longer believed the brain has a central “music region”. The listening and processing of music occurs throughout many regions of the brain. In fact, music occupies more regions of the brain than language does! Despite this, the auditory cortex of the brain (pictured at right) has been shown to have strong ties to the motor regions of the brain. People with neurological disorders (strokes, Parkinson’s disease, etc.) have often been found to have improved neurological function after receiving music therapy.

One final interesting scientific argument discussed in this program is the origin of music, specifically what evolved first: music or language? Many scientists believe it is language which developed first, but The Music Instinct provides compelling evidence that suggests perhaps it is music which evolved first. A 2001 Scientific American article suggests that music not only predates language, but may be more ancient than the human race. For those who have watched the news, or traveled to foreign countries, you can see time after time how all types of music, in a different language than the listeners’ native language, influences the emotional behavior of those that are listening.

Music is indeed a universal form of communication which may supersede language. If so, maybe the next time I encounter a foreigner, instead of trying to say “Hello” I will jam out some Beatles tunes!

Trailer:

The Music Instinct: Science and Song was released on DVD November 4.

NeuroScribe obtained a B.S. in Biology, and a Ph.D. in Cell Biology with a strong emphasis in Neuroscience. When he’s not busy freelancing for ScriptPhD.com he is out in the field perfecting his photography, reading science policy, and throwing some Frisbee.

~*NeuroScribe*~

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and pop culture. Follow us on Twitter and our Facebook fan page. Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.