The biggest threat to mankind may not end up being an enormous weapon; in fact, it might be too small to visualize without a microscope. Between global interconnectedness and instant travel, the age of genomic manipulation, and ever-emerging infectious disease possibilities, our biggest fears should be rooted in global health and bioterrorism. We got a recent taste of this with Stephen Soderberg’s academic, sterile 2011 film Contagion. Helix, a brilliant new sci-fi thriller from Battlestar Galactica creator Ronald D. Moore, isn’t overly concerned with whether the audience knows the difference between antivirals and a retrovirus or heavy-handed attempts at replicating laboratory experiments and epidemiology lectures. What it does do is explore infectious disease outbreak and bioterrorism in the greater context of global health and medicine in a visceral, visually chilling way. In the world of Helix, it’s not a matter of if, just when… and what we do about it after the fact. ScriptPhD.com reviews the first three episodes under the “continue reading” cut.

The benign opening scenes of Helix take place virtually every day at the Centers for Disease Control, along with global health centers all over the world. Dr. Alan Farragut, leader of a CDC outbreak team, is assembling and training a group of researchers to investigate a possible viral outbreak at a remote research called Arctic Biosystems. Tucked away in Antarctica under extreme working conditions, and completely removed from international oversight, the self-contained building employs 106 scientists from 35 countries. One of these scientists, Dr. Peter Farragut, is not only Alan’s brother but also appears to be Patient Zero.

It doesn’t take the newly assembled team long to discover that all is not as it seems at Arctic Biosystems. Deceipt and evasiveness from the staff lead to the discovery of a frightening web of animal research, uncovering the tip of an iceberg of ‘pseudoscience’ experimentation that may have led to the viral outbreak, among other dangers. The mysterious Dr. Hiroshi Hatake, the head of Ilaria Corporation, which runs the facility, may have nefarious motivations, yet is desperately reliant on the CDC researchers to contain the situation. The involvement of the US Army engineers and scientists, culminating in a shocking, devastating ending to the third episode, hints that the CDC doesn’t think the outbreak was accidental. Most frightening of all is the discovery of two separate strains of the virus, Narvic A and Narvic B, the former of which turns victims into a bag of Ebola-like hemorrhagic black sludge, while the latter rewires the brain to create superhuman strength – a perfect contagion machine.

With some pretty brilliant sci-fi minds orchestrating the series, including Moore, Lost alum Steven Maeda and Contact producer Lynda Obst, it’s not surprising that Helix extrapolates extremely accurate and salient themes facing today’s scientific environment. Spot on is the friction between communication and collaboration between the agencies depicted on the show – the CDC, bioengineers from the US Army and the fictional Arctic Biosystems research facility. In reality, identifying and curtailing emerging infectious disease outbreaks requires a network of collaboration among, chiefly, the World Health Organization, the CDC, the US Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases (USAMRIID, famously portrayed in the film Outbreak) and local medical, research and epidemiological outposts at the outbreak site(s). In addition to managing egos, agencies must quickly share proprietary data and balance global oversight (WHO) with local and federal juristictions, which can be a challenge even under ordinary conditions. To that extent, including a revised set of international health regulations in 2005 and the establishment of an official highly transimissible form of the virus created a hailstorm of controversy. In addition to a publishing moratorium of 60 days and censorship of key data, debate raged on the necessity of publishing the findings at all from a national security standpoint and the benefit to risk value of such “dual-use” research. Similar fears of “playing God” were stoked after the creation of a fully synthetic cell by J. Craig Venter and the team behind the Genome Project.

As with Moore’s other SyFy series, Battlestar Galactica, Helix is not perfect, and will need time and patience (from both the network and viewing audience) to strike the right chemistry and develop evenness in its storytelling. The dialogue feels forced at times, particularly among the lead characters and with rapid fire high-level scientific jargon, of which there is a surprising amount. Certain scenes involving the gruesomeness of the viruses feel too long and repetitive in the first episodes, but this will quickly dissipate as the plot develops. But for all of its minor blemishes, Helix is one of the smartest scientific premises to hit television in recent times, and looks to deftly explore familiar sci-fi themes of bioengineering ethics and the risks of ‘playing God’ just because we have the technology to do so.

We’ve become accustomed to sci-fi terrifying us visually, such as the ‘walker’ zombies of The Walking Dead or even psychologically, as in the recent hit movie Gravity. But Helix’s terror is drawn from the utter plausibility of the scenario it presents.

View an extended 15 minute sample of the Helix pilot here:

Helix will air on Friday nights at 10:00 PM ET/PT on SyFy channel.

~*ScriptPhD*~

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire us for creative content development.

Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

]]>

We are in the midst of a pandemic, folks. A pandemic of fear. A truly formidable novel strain of influenza (H1N1) is spreading worldwide, creating an above-average spike in seasonal illness, the genuine possibility of a global influenza pandemic, and an alarmed public bombarded with opposing facts and mixed messages. It’s understandable that all of this has left people confused, scared and unsure of how to proceed. ScriptPhD.com cuts through the fray to provide a compact, easy-to-understand discussion of the science behind influenza as well as invaluable public health resources for addressing additional questions and concerns. Our discussion includes the role of media and advertising in not only informing the public responsibly, but effecting behavioral change that can save lives. Our full article, under the “continue reading” jump.

The Biology of How Flu Works

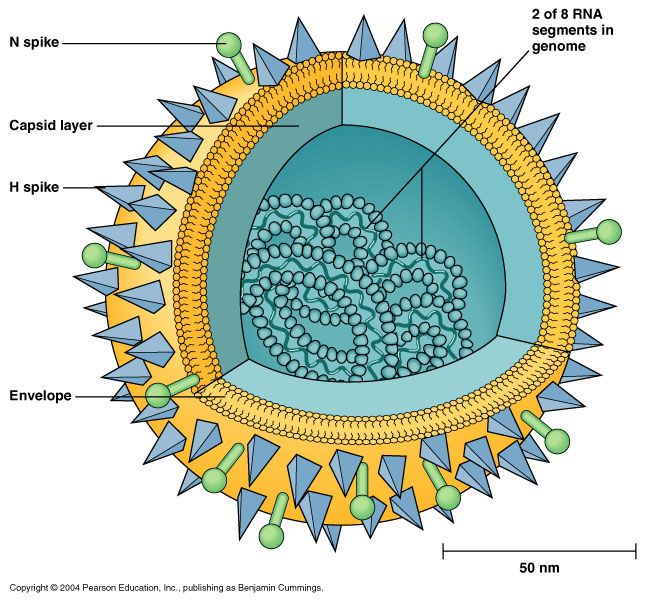

Before embarking on a long-winded discussion of flu, the H1N1 strain, vaccines, and media responsibility in the post-internet age, it’s best to start with some rudimentary facts about exactly what the influenza virus is and how it invades and replicates in the human body. While the human genome consists of a whopping 23,000 genes, the influenza virus is relatively simple. Only 8 genes, responsible for creating 11 unique proteins of the influenza genome, can ruin your whole winter. Of those 8, the most important two are the blue H spike (Hemagglutinin or HA) and the green N spike (Neuraminidase or NA). When people refer to strains of flu, such as H1N1, H2N1, H5N1, they are talking about the different genetic “mixes and matches” of the available subtypes of HA, of which there are currently 16, and NA, of which there are 9 to date. Luckily for humans, only small permutations of these end up posing a danger to our healths: the first three hemagglutinins (H1, H2, and H3) and selective neuraminidases (N1 and N2 in pandemics and N3 and N7 in isolated deaths) are found in human influenzas. Predicting future deadly combinations of the HA and NA enzymes with a degree of certainty presents an enormous challenge to biologists.

Think of the H spike and N spike as the Bonnie and Clyde of influenza infection—they have to work together to pull off the heist. The H spike finds special receptors on the surface of cells that contain an organic molecule called sialic acid, which it then sticks to and uses to form a chemical bond between the virus and the cell, like a lock going into a key. But as long as the blue H spikes are clutching to the cell’s surface, the virus is immobile. So the N spike comes along and cleaves the sialic acid chemical bond, the virus is free to make itself at home and you are one sick camper. The two current influenza drugs on the market Relenza and Tamiflu act as inhibitors, or blockers, of the NA enzyme.

In what is the best visual representation I have ever seen of how flu invades and replicates in the body, NPR teamed up with medical animator David Bolinsky to explain how one lone virus copy turns into millions by using your body’s own DNA machinery.

Seasonal Flu vs. Pandemics, A Big Difference

Each year, approximately 250,000 to 500,000 people die worldwide of influenza (36,000 in the United States). This “seasonal flu”, an infection of the respiratory tract, primarily kills high-risk populations—older people, children, pregnant women and immunocompromized patients. Seasonal flu epidemics are caused by the circulation of a group of viruses, primarily Type A, that have already presented in the human population and for which we have developed vaccines and built-up immunity. A flu pandemic requires the introduction of a new type of virus for which we have not developed innate immunity under the following conditions:

•presence of a brand new virus subtype in the human population (usually mutated from an animal form of influenza)

•the virus is capable of causing serious illness in humans (something H5N1 bird flu, for example, is not yet able to do)

•the virus can spread easily from person to person

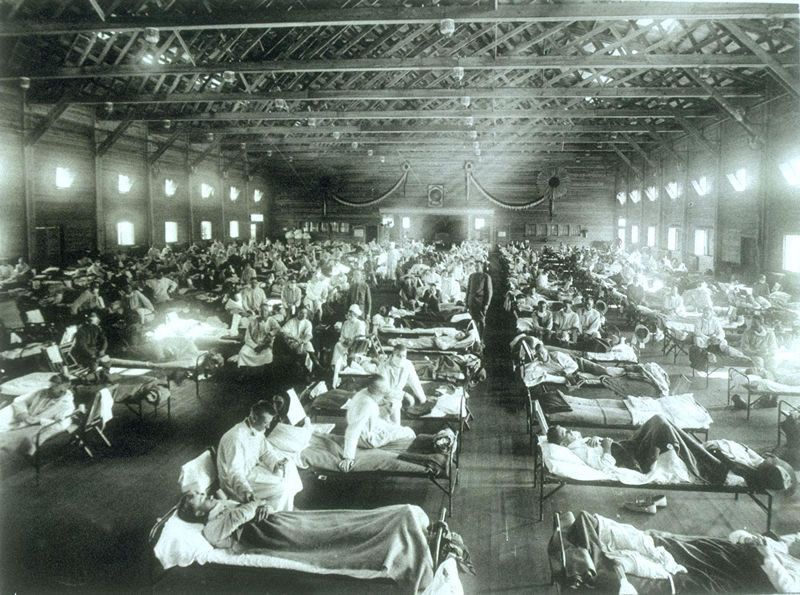

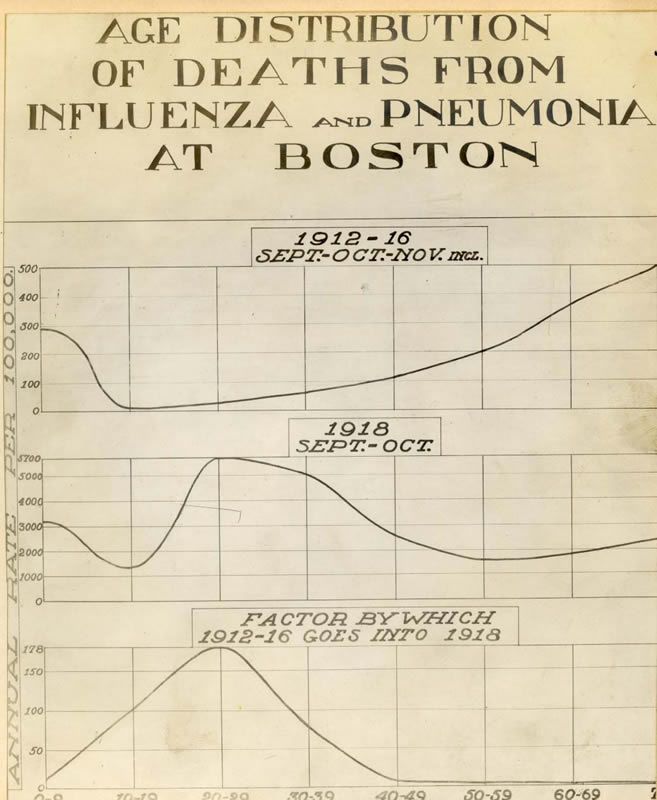

There have been three major post-industrial pandemics: the 1957 Asian flu, the 1968 Hong Kong flu and of course, the 1918 Spanish flu. The 1918 pandemic, one of the worst public health disasters of all time, killed 50 million people worldwide (a conservative estimate) at a time when the global population was only 2 billion—yes, 2.5% of the world’s population. It is said to have killed more people than the Black Plauge and the AIDS epidemic. Besides the three provisions discussed above, there is one major difference between pandemics and yearly epidemics: how they kill. The graph on the right, containing preserved data from 1918 shows two different death curves, one from regular epidemics in and around the Spanish Flu, and another from the Spanish Flu itself. Normally, yearly flu primarily kills the extremely young and extremely old, what epidemiologists call a “U-shaped curve”. Pandemics such as the 1918 flu kill primarily healthy young people, resulting in a “W-shaped curve”. World Bank economist Milan Brahmbhatt estimated that the economic toll of a similar pandemic, due to the loss of such a chunk of the healthy work force, would be approximately 2% of the world’s GDP.

So why all the fuss about H1N1 swine flu, and is it warranted? From a public health epidemiology standpoint… yes. Biological mapping and sequencing has revealed the H1N1 virus to be a novel mutation that has not circulated in human populations before this year. It has also fulfilled all of the requirements to be classified as a pandemic. On June 11th, Dr. Margaret Chan, Director-General of the World Health Organization declared H1N1 at the start of a worldwide flu pandemic. Just a week ago, President Obama declared a state of emergency in the United States to help mitigate the spread of H1N1. To date, it has killed approximately 6,000 people worldwide, with the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control estimating an 11% increase in deaths just this week. While it is not a preordained certainty that H1N1 will absolutely result in a global pandemic carrying a similar degree of severity to any of the three from the 20th Century, it has enough disconcerting characteristics and pandemic potential to validate scientists’ calls for preventive measures, including vaccination and anti-viral stockpiles. For a terrific rundown and rebuttal of some common swine flu myths, I recommend this New Scientist article.

I also feel the need to address controversy surrounding the H1N1 vaccine, which has been both unduly vilified in the general population and improperly explained by the general media (a subject we’ll delve into in a moment). Fewer than half of Americans say they are planning on getting the H1N1 vaccine for a multitude of reasons, not the least of which include complacency about the virus potency and fear of side effects from the vaccine. While we have strived to address questions about the H1N1 virus above, I cannot state this more strongly or definitively: the vaccine developed for H1N1 is not being manufactured any differently than seasonal vaccines. It has the same ingredients, safety profile, and side effects (rare). The official flu site of the U.S. Government provides an excellent overview of vaccine safety and ingredients as well as a link for common questions and answers.

How Smart Media and Advertising Could Save Lives

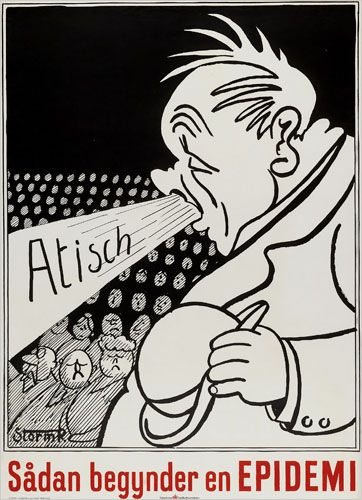

The idea of advertising and marketing as tools to combat public health crises is certainly nothing new. As early as the 1860s, and peaking during the two World Wars, clever taglines married beautiful artwork to combat everything from venereal disease to tuberculosis, and they worked. Now a permanent collection of 20th-century health posters at the National Library of Medicine, these compelling, cheeky visual messages changed soldiers’ sexual habits abroad, cultural norms around communicable diseases, and widespread awareness of rising epidemics. Those campaigns were, of course, launched during a less cluttered technological era, but sometimes, simple, smart advertising can be the most effective.

Especially in today’s age of multitudinous multi-functional multimedia, more information can just mean… more information. A recent study from the World Bank addressed why we don’t do much about climate change despite the plethora of data that conclusively deduces we must. The reasoning? An influx of too much information and not enough targeting of individual behaviors. And make no mistake that advertising has an enormous subconscious influence on our behavior. A seminal paper out of the Yale University Psychology Department earlier this year showed external cues from television advertising increased food consumption 45% in children and adults irrespective of hunger. There is no reason that such enormous influence can’t and shouldn’t be harnessed in eliciting positive behavioral changes during the 2009-2010 flu season (and beyond).

The media in particular, with their highly sensationalized mood swing swine flu coverage, has played an enormously irresponsible role in fanning the fires of public fear and misinformation. Remember the desolate empty streets of Mexico City? Or the U.S. pre-emptively declaring a public health emergency? Quarantines, social distancing, vaccine and Tamiflu stockpiles, dire expert warnings, surely, impending doom was imminent. And when it wasn’t, the Great Swine Flu Scare of spring turned into a Great Swine Flu Joke of the summer— literally. Social media satire included Facebook and Twitter pages seemingly run by the swine flu itself and a hilarious interview with the Los Angeles Times. The humor underscored a more serious swine flu fatigue incurred by intense media saturation, often missing key scientific information or balanced reporting. In its analysis of swine flu accuracy in the media, the Columbia Journalism Review recently lambasted the ubiquitous hype, and the cognitive dissonance between fact and fiction in reporting by “respected” journalism outlets.

Worse than these confusing messages is the tapestry of opinions masquerading as fact about a subject buoyed by plenty of sound science and research. The most egregious offender of late was Bill Maher, who used his show as a bully pulpit to decry immunization with the H1N1 vaccine, and the severity of H1N1 itself, in an interview so fraught with misguided medicine and unsound reasoning (the majority of which we’ve addressed above) that it pains me to give it publicity on my site. The video is worth a view if only for the rebuttals of a more rational Bill, former Senate majority leader Dr. Frist.

The use of advertising as a viral public health campaign is a double edged sword. Back in 1976, an earlier wave of swine flu fear gripped the nation. Like the 2009 strain, it was unseen in the general population since the 1918 flu, and touched off a similar wave of national panic about whether a widespread plague threatened the entire United States. In what has argued as both public health’s finest hour and the swine flu “fiasco”, President Gerald Ford decided all 220 million Americans had to be immunized, and ordered hasty production of an untested vaccine that killed over 500 Americans and was ultimately halted as unsafe. Part of the government propaganda to encourage vaccination included the two frightening television commercials below.

As detailed in Arthur M. Silverstein’s book “Pure Politics and Impure Science” (a good summary can be found here), the aftermath and deleterious impact on trust in the public health infrastructure was multi-generational and devastating, perhaps even emanating in the skepticism towards the 2009 vaccine, despite entirely different safety guidelines and circumstances. A smarter approach to engaging the public is a current BBC television spot done in concert with the British Government:

This is such an excellent piece on multiple fronts. The tagline—catch it, bin it, kill it—effectively communicates sound hygiene and advocates hand washing, still by far the most potent way to ward off germs and prevent illness. It’s sleek, clever, funny, and most importantly, gross! I washed my hands after just viewing it. In conjunction with print ads, billboards and yes, old-fashioned posters, similar public service announcements should be placed during the most popular primetime television shows, sporting events, concerts, other public gatherings, and most importantly, as part of any in-flight boarding process.

What’s a Confused Germaphobe To Do?

Despite the circulation of conflicting information and influx of divergent opinions, there are some genuinely useful resources and recommendations for this flu season. Here’s a good start:

Get a flu shot! Immunization against influenza, both the seasonal and H1N1 strains, remains the only surefire effective defense against the viruses. One of the most solid and eloquent arguments for the flu shot that I’ve seen comes from Dr. William Marshall, an infectious diseases specialists at the Mayo Clinic:

Wash your hands! Short of getting vaccinated, there is no easier, cheaper, faster, more effective way of preventing colds and flu. In fact, the CDC estimates that 80% of all seasonal flu is spread by hand contact. However, not only do you need to wash your hands, you need to do so properly.

Eat, drink, sleep Never underestimate the role that good nutrition, plenty of water, and a good night’s rest can have to boost the immune system and help it naturally combat exposure to viruses, especially if you make the choice to abstain from the flu vaccine. Of all three, sleep is the most critical. Read this fascinating NY Science Times article from earlier this fall about a sleep study that showed a direct correlation between lack of sleep and increased likelihood of catching a cold.

Accept no imitations Yes, Virginia, people try to take advantage and scam even in a pandemic. Color yourself shocked. The government is issuing warnings about a growing list of Swine Flu scams, some of which could be deadly. Remember, only Tamiflu and Relenza are recommended as flu treatments and only your doctor can prescribe them. The FDA has also issued a comprehensive list of fraudulent H1N1 products, including air purifiers, soaps, masks and other concoctions. Before buying ANYTHING that claims to prevent or combat the flu, please refer to it.

Get technical Thanks to the wonders of modern technology, it’s easier than ever to track the flu, know how to prevent it and what to do if you get it. Flu.gov, the WebMD Focus on the Flu site, and the Centers for Disease Control flu homepage are excellent educational starting points. Google now provides a flu tracker to explore the severity of flu trends around the world. And for those of you that are, like the ScriptPhD, of the iPhone persuasion, a new iPhone application called “Outbreaks Near Me” developed at MIT, and available as a free download, provides GPS data on outbreak clusters in your neighborhood.

If you have any other tips, cool gadgetry, public health resources or web sites we should add to our list, please don’t hesitate to comment or email me.

~*ScriptPhD*~

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and pop culture. Follow us on Twitter and our Facebook fan page. Subscribe to email alerts for new posts on our home page.