We are in the midst of a pandemic, folks. A pandemic of fear. A truly formidable novel strain of influenza (H1N1) is spreading worldwide, creating an above-average spike in seasonal illness, the genuine possibility of a global influenza pandemic, and an alarmed public bombarded with opposing facts and mixed messages. It’s understandable that all of this has left people confused, scared and unsure of how to proceed. ScriptPhD.com cuts through the fray to provide a compact, easy-to-understand discussion of the science behind influenza as well as invaluable public health resources for addressing additional questions and concerns. Our discussion includes the role of media and advertising in not only informing the public responsibly, but effecting behavioral change that can save lives. Our full article, under the “continue reading” jump.

The Biology of How Flu Works

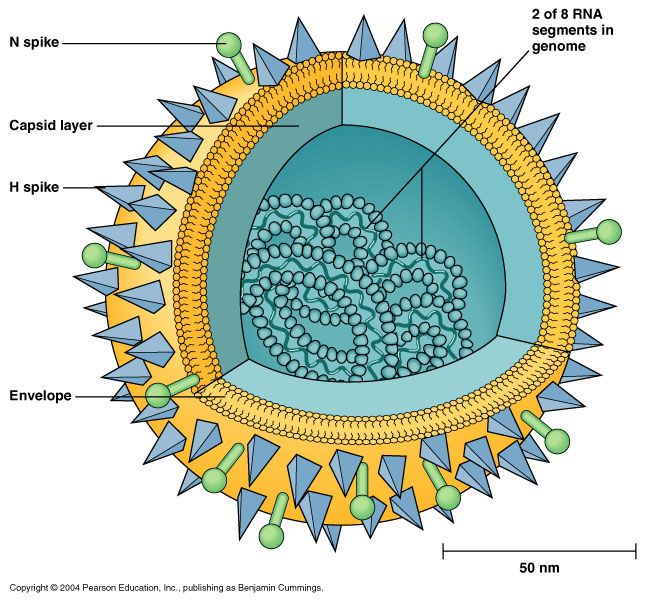

Before embarking on a long-winded discussion of flu, the H1N1 strain, vaccines, and media responsibility in the post-internet age, it’s best to start with some rudimentary facts about exactly what the influenza virus is and how it invades and replicates in the human body. While the human genome consists of a whopping 23,000 genes, the influenza virus is relatively simple. Only 8 genes, responsible for creating 11 unique proteins of the influenza genome, can ruin your whole winter. Of those 8, the most important two are the blue H spike (Hemagglutinin or HA) and the green N spike (Neuraminidase or NA). When people refer to strains of flu, such as H1N1, H2N1, H5N1, they are talking about the different genetic “mixes and matches” of the available subtypes of HA, of which there are currently 16, and NA, of which there are 9 to date. Luckily for humans, only small permutations of these end up posing a danger to our healths: the first three hemagglutinins (H1, H2, and H3) and selective neuraminidases (N1 and N2 in pandemics and N3 and N7 in isolated deaths) are found in human influenzas. Predicting future deadly combinations of the HA and NA enzymes with a degree of certainty presents an enormous challenge to biologists.

Think of the H spike and N spike as the Bonnie and Clyde of influenza infection—they have to work together to pull off the heist. The H spike finds special receptors on the surface of cells that contain an organic molecule called sialic acid, which it then sticks to and uses to form a chemical bond between the virus and the cell, like a lock going into a key. But as long as the blue H spikes are clutching to the cell’s surface, the virus is immobile. So the N spike comes along and cleaves the sialic acid chemical bond, the virus is free to make itself at home and you are one sick camper. The two current influenza drugs on the market Relenza and Tamiflu act as inhibitors, or blockers, of the NA enzyme.

In what is the best visual representation I have ever seen of how flu invades and replicates in the body, NPR teamed up with medical animator David Bolinsky to explain how one lone virus copy turns into millions by using your body’s own DNA machinery.

Seasonal Flu vs. Pandemics, A Big Difference

Each year, approximately 250,000 to 500,000 people die worldwide of influenza (36,000 in the United States). This “seasonal flu”, an infection of the respiratory tract, primarily kills high-risk populations—older people, children, pregnant women and immunocompromized patients. Seasonal flu epidemics are caused by the circulation of a group of viruses, primarily Type A, that have already presented in the human population and for which we have developed vaccines and built-up immunity. A flu pandemic requires the introduction of a new type of virus for which we have not developed innate immunity under the following conditions:

•presence of a brand new virus subtype in the human population (usually mutated from an animal form of influenza)

•the virus is capable of causing serious illness in humans (something H5N1 bird flu, for example, is not yet able to do)

•the virus can spread easily from person to person

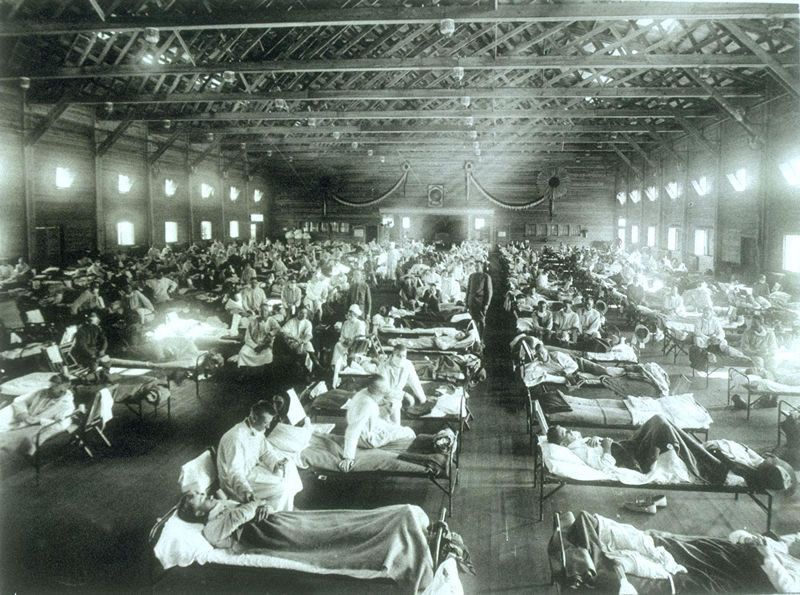

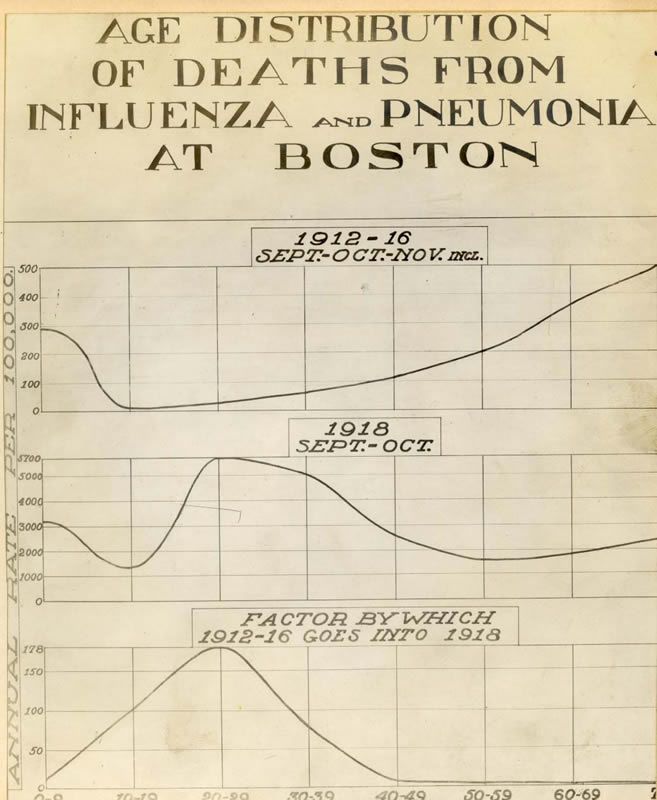

There have been three major post-industrial pandemics: the 1957 Asian flu, the 1968 Hong Kong flu and of course, the 1918 Spanish flu. The 1918 pandemic, one of the worst public health disasters of all time, killed 50 million people worldwide (a conservative estimate) at a time when the global population was only 2 billion—yes, 2.5% of the world’s population. It is said to have killed more people than the Black Plauge and the AIDS epidemic. Besides the three provisions discussed above, there is one major difference between pandemics and yearly epidemics: how they kill. The graph on the right, containing preserved data from 1918 shows two different death curves, one from regular epidemics in and around the Spanish Flu, and another from the Spanish Flu itself. Normally, yearly flu primarily kills the extremely young and extremely old, what epidemiologists call a “U-shaped curve”. Pandemics such as the 1918 flu kill primarily healthy young people, resulting in a “W-shaped curve”. World Bank economist Milan Brahmbhatt estimated that the economic toll of a similar pandemic, due to the loss of such a chunk of the healthy work force, would be approximately 2% of the world’s GDP.

So why all the fuss about H1N1 swine flu, and is it warranted? From a public health epidemiology standpoint… yes. Biological mapping and sequencing has revealed the H1N1 virus to be a novel mutation that has not circulated in human populations before this year. It has also fulfilled all of the requirements to be classified as a pandemic. On June 11th, Dr. Margaret Chan, Director-General of the World Health Organization declared H1N1 at the start of a worldwide flu pandemic. Just a week ago, President Obama declared a state of emergency in the United States to help mitigate the spread of H1N1. To date, it has killed approximately 6,000 people worldwide, with the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control estimating an 11% increase in deaths just this week. While it is not a preordained certainty that H1N1 will absolutely result in a global pandemic carrying a similar degree of severity to any of the three from the 20th Century, it has enough disconcerting characteristics and pandemic potential to validate scientists’ calls for preventive measures, including vaccination and anti-viral stockpiles. For a terrific rundown and rebuttal of some common swine flu myths, I recommend this New Scientist article.

I also feel the need to address controversy surrounding the H1N1 vaccine, which has been both unduly vilified in the general population and improperly explained by the general media (a subject we’ll delve into in a moment). Fewer than half of Americans say they are planning on getting the H1N1 vaccine for a multitude of reasons, not the least of which include complacency about the virus potency and fear of side effects from the vaccine. While we have strived to address questions about the H1N1 virus above, I cannot state this more strongly or definitively: the vaccine developed for H1N1 is not being manufactured any differently than seasonal vaccines. It has the same ingredients, safety profile, and side effects (rare). The official flu site of the U.S. Government provides an excellent overview of vaccine safety and ingredients as well as a link for common questions and answers.

How Smart Media and Advertising Could Save Lives

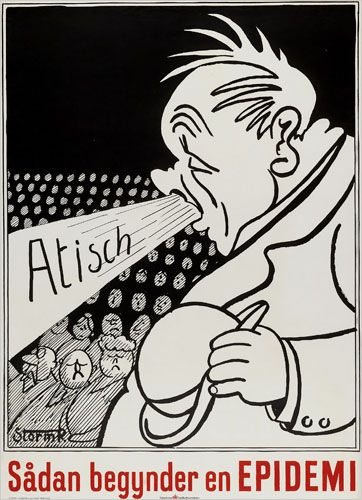

The idea of advertising and marketing as tools to combat public health crises is certainly nothing new. As early as the 1860s, and peaking during the two World Wars, clever taglines married beautiful artwork to combat everything from venereal disease to tuberculosis, and they worked. Now a permanent collection of 20th-century health posters at the National Library of Medicine, these compelling, cheeky visual messages changed soldiers’ sexual habits abroad, cultural norms around communicable diseases, and widespread awareness of rising epidemics. Those campaigns were, of course, launched during a less cluttered technological era, but sometimes, simple, smart advertising can be the most effective.

Especially in today’s age of multitudinous multi-functional multimedia, more information can just mean… more information. A recent study from the World Bank addressed why we don’t do much about climate change despite the plethora of data that conclusively deduces we must. The reasoning? An influx of too much information and not enough targeting of individual behaviors. And make no mistake that advertising has an enormous subconscious influence on our behavior. A seminal paper out of the Yale University Psychology Department earlier this year showed external cues from television advertising increased food consumption 45% in children and adults irrespective of hunger. There is no reason that such enormous influence can’t and shouldn’t be harnessed in eliciting positive behavioral changes during the 2009-2010 flu season (and beyond).

The media in particular, with their highly sensationalized mood swing swine flu coverage, has played an enormously irresponsible role in fanning the fires of public fear and misinformation. Remember the desolate empty streets of Mexico City? Or the U.S. pre-emptively declaring a public health emergency? Quarantines, social distancing, vaccine and Tamiflu stockpiles, dire expert warnings, surely, impending doom was imminent. And when it wasn’t, the Great Swine Flu Scare of spring turned into a Great Swine Flu Joke of the summer— literally. Social media satire included Facebook and Twitter pages seemingly run by the swine flu itself and a hilarious interview with the Los Angeles Times. The humor underscored a more serious swine flu fatigue incurred by intense media saturation, often missing key scientific information or balanced reporting. In its analysis of swine flu accuracy in the media, the Columbia Journalism Review recently lambasted the ubiquitous hype, and the cognitive dissonance between fact and fiction in reporting by “respected” journalism outlets.

Worse than these confusing messages is the tapestry of opinions masquerading as fact about a subject buoyed by plenty of sound science and research. The most egregious offender of late was Bill Maher, who used his show as a bully pulpit to decry immunization with the H1N1 vaccine, and the severity of H1N1 itself, in an interview so fraught with misguided medicine and unsound reasoning (the majority of which we’ve addressed above) that it pains me to give it publicity on my site. The video is worth a view if only for the rebuttals of a more rational Bill, former Senate majority leader Dr. Frist.

The use of advertising as a viral public health campaign is a double edged sword. Back in 1976, an earlier wave of swine flu fear gripped the nation. Like the 2009 strain, it was unseen in the general population since the 1918 flu, and touched off a similar wave of national panic about whether a widespread plague threatened the entire United States. In what has argued as both public health’s finest hour and the swine flu “fiasco”, President Gerald Ford decided all 220 million Americans had to be immunized, and ordered hasty production of an untested vaccine that killed over 500 Americans and was ultimately halted as unsafe. Part of the government propaganda to encourage vaccination included the two frightening television commercials below.

As detailed in Arthur M. Silverstein’s book “Pure Politics and Impure Science” (a good summary can be found here), the aftermath and deleterious impact on trust in the public health infrastructure was multi-generational and devastating, perhaps even emanating in the skepticism towards the 2009 vaccine, despite entirely different safety guidelines and circumstances. A smarter approach to engaging the public is a current BBC television spot done in concert with the British Government:

This is such an excellent piece on multiple fronts. The tagline—catch it, bin it, kill it—effectively communicates sound hygiene and advocates hand washing, still by far the most potent way to ward off germs and prevent illness. It’s sleek, clever, funny, and most importantly, gross! I washed my hands after just viewing it. In conjunction with print ads, billboards and yes, old-fashioned posters, similar public service announcements should be placed during the most popular primetime television shows, sporting events, concerts, other public gatherings, and most importantly, as part of any in-flight boarding process.

What’s a Confused Germaphobe To Do?

Despite the circulation of conflicting information and influx of divergent opinions, there are some genuinely useful resources and recommendations for this flu season. Here’s a good start:

Get a flu shot! Immunization against influenza, both the seasonal and H1N1 strains, remains the only surefire effective defense against the viruses. One of the most solid and eloquent arguments for the flu shot that I’ve seen comes from Dr. William Marshall, an infectious diseases specialists at the Mayo Clinic:

Wash your hands! Short of getting vaccinated, there is no easier, cheaper, faster, more effective way of preventing colds and flu. In fact, the CDC estimates that 80% of all seasonal flu is spread by hand contact. However, not only do you need to wash your hands, you need to do so properly.

Eat, drink, sleep Never underestimate the role that good nutrition, plenty of water, and a good night’s rest can have to boost the immune system and help it naturally combat exposure to viruses, especially if you make the choice to abstain from the flu vaccine. Of all three, sleep is the most critical. Read this fascinating NY Science Times article from earlier this fall about a sleep study that showed a direct correlation between lack of sleep and increased likelihood of catching a cold.

Accept no imitations Yes, Virginia, people try to take advantage and scam even in a pandemic. Color yourself shocked. The government is issuing warnings about a growing list of Swine Flu scams, some of which could be deadly. Remember, only Tamiflu and Relenza are recommended as flu treatments and only your doctor can prescribe them. The FDA has also issued a comprehensive list of fraudulent H1N1 products, including air purifiers, soaps, masks and other concoctions. Before buying ANYTHING that claims to prevent or combat the flu, please refer to it.

Get technical Thanks to the wonders of modern technology, it’s easier than ever to track the flu, know how to prevent it and what to do if you get it. Flu.gov, the WebMD Focus on the Flu site, and the Centers for Disease Control flu homepage are excellent educational starting points. Google now provides a flu tracker to explore the severity of flu trends around the world. And for those of you that are, like the ScriptPhD, of the iPhone persuasion, a new iPhone application called “Outbreaks Near Me” developed at MIT, and available as a free download, provides GPS data on outbreak clusters in your neighborhood.

If you have any other tips, cool gadgetry, public health resources or web sites we should add to our list, please don’t hesitate to comment or email me.

~*ScriptPhD*~

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and pop culture. Follow us on Twitter and our Facebook fan page. Subscribe to email alerts for new posts on our home page.

When was the last time that you tuned into CNN in the midst of a developing global crisis and heard about the power of software technology? The more likely scenario is a cavalcade of jarring images—displaced children wading knee-deep in floodwaters, distraught earthquake victims climbing through the rubble of utter destruction, panic embodied in a sea of facemasks—coupled with desperate pleas for food, water, medical supplies, donations, and on-the-ground manpower. But how is information assessed and distributed to the humanitarian relief agencies and governments that converge on often under developed disaster zones? And who enables the logistics of distributing supplies where needed in the middle of chaos? Rarely, if ever, is enough credit given to the technology, web and software support that coordinates these efforts and makes them possible. Microsoft has been using technology to help respond to and manage the effects of natural disasters through its local impacted offices for many years, but in 2007, Microsoft Corporation formally launched a centralized Microsoft® Disaster Response program expanding its breadth and depth in reach to provide sustaining global coverage. For our full profile and exclusive sit-down interview with Program Director Claire Bonilla, please click “continue reading”.

The Microsoft Disaster Response program is dedicated to improving response capabilities of disaster response organizations, customers and partners by utilizing core resources to provide Information and Communications Technology (ICT) solutions. The foundation of the program rests on three pillars of response: information and communications technology leadership, forming global partnerships and community involvement. A few of the platforms that Microsoft has either adapted or developed specifically for disaster response include: the Bing™ Maps (formerly Virtual Earth™) solution for visualizing location-based data, Microsoft SharePoint collaboration portal, modeled for inter- and intra-agency communication and collaboration, Microsoft Vine™, a beta multi-platform communication tool that streamlines people tracking and dissemination of information during disasters, and Microsoft Citizen Safety Architecture, a conglomeration of software services that facilitate operational effectiveness through data sharing between organizations.

Microsoft’s response to natural disasters around the world manifests itself in the form of technology solutions, employee engagement and monetary support. After the 2008 earthquake in China’s Sichuan province, Microsoft China Technology Center engineers, as well as partners, volunteered their time and expertise to upgrade the China Red Cross Foundation website that had faltered after being inundated with traffic and donation transactions. In addition to the technology solutions support, Microsoft and employees donated an initial $1.7 million for earthquake relief, with Microsoft pledging an additional $1.4 million over two years for rebuilding efforts. Microsoft also worked with the US Red Cross after Hurricane Katrina in 2005 to create their still-utilized Safe and Well web site, a portal that reunites individuals and families affected by disaster, allowing them to share information about their location and condition. Microsoft and its employees also contributed more than $11 million in cash donations. Likewise, when the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami devastated large portions of Southeast Asia, Microsoft and employees provided technology assistance, donated over $7.6 million and provided microloans to tsunami victims. Additionally, they worked with local relief agencies to establish the “Network of Rural Knowledge Centers” to provide community connectivity, technology training, and rehabilitation. In 2008, Cyclone Nargis devastated Myanmar (formerly Burma), with over 138,000 fatalities, and millions more left homeless. Microsoft joined with 19 partners to build a collaborative web portal for the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs to coordinate aid workers. Patrick Gordon, technical coordinator with UN OCHA affirmed that the portal technology “[was] a phenomenal asset in terms of improving our situational awareness and coordination.”

Microsoft has implemented company-wide policies to encourage employee participation and engagement in crisis outreach. The policies include: matching charity donations of up to $12,000, and a $17-per-hour cash match for time volunteered within the United States by employees at nonprofits, and three paid days of volunteer time with qualified NGOs for international employees. As a result, Microsoft employees’ time and generosity has been rapidly mobilized in the aforementioned disasters, along with a number of domestic emergencies, including the 2007 California wildfires, the 2009 floods in Fargo, ND and Hurricanes Gustav and Ike in the US Gulf states.

The Disaster Response program is led by Senior Director Claire Bonilla. Mrs. Bonilla graduated from Willamette University with a BA in Economics and German, and got her Master’s in economics from the London School of Economics. In a terrific primer for helming the Disaster Response program at Microsoft, she held a previous position at the prestigious accounting firm Ernst & Young as an organizational efficiency consultant. In a recent Wall Street Journal profile, Mrs. Bonilla credited her success in her current job to a background in helping communities, from early age participation in volunteering to supporting a community affairs and volunteerism group at Willamette University. “I’m emotionally and genetically engineered to help people,” Bonilla says. ScriptPhD.com was extraordinarily fortunate to sit down with a very busy Mrs. Bonilla to talk about the program, to get behind the scenes of some of Microsoft’s more recent work with the H1N1 influenza outbreak, and discuss the potent capacity of technology to bolster response efforts of governments and global health organizations in times of crisis.

Interview with Claire Bonilla, Director of the Microsoft’s Disaster Response Program:

ScriptPhD: Tell me about your role in the Disaster Response program.

Claire Bonilla: I oversee Microsoft’s Disaster Response strategy and operations. When there is a natural disaster anywhere in the world, I run our operations and response center to reach out to governments, intergovernmental organizations like the United Nations, and non-government organizations that are leading response efforts in that area to see how we can assist them and increase their capability by using technology. The other role that I have is to work with a very talented cross-company team where we don’t just look at response; we examine how to help increase the capacity of communities to be more resilient and reduce the consequences of disasters. To accomplish that, you have to focus on the entire disaster lifecycle: prevention, preparedness, response, and recovery. It goes beyond just helping with response efforts. We work across all four of the pillars of the disaster management cycle to make sure that these communities are more resilient in the face of disasters, reducing consequences and aiding in recovery efforts. Once an incident has occurred, they have an opportunity to build the community beyond the original level and increase the capabilities of that community to mitigate the impact of the next disaster.

SPhD: Yes, for example in influenza [research], one of the ways technology is used is for modeling, which would help simulate, for example if you ever had to do social distancing measures or mitigation strategies for vaccine distribution. A lot of times, technology plays a big role in preparing scientists in saying, “Worst case scenario, what are we looking at here and what are we dealing with?”

CB: Exactly.

SPhD: How does Microsoft engage with NGOs and global health organizations?

CB: The Disaster Response program efforts are focused on three key constituents, of which those are two. We work with global health organizations (intergovernmental organizations or IGOs) and governments, non-government organizations, and our customers and partners. As an example, we worked very closely with both government health agencies and NGOs in response to the H1N1 influenza outbreak. Our goal is to make sure that these three types of organizations understand the value that technology can offer to help them manage disasters better. There are three core ways that we work with our constituents: providing information, communication technology (ICT) and leadership, utilizing global partnerships, and fostering community involvement.

Microsoft has technology solutions and a network of about 750,000 partners worldwide, which enables us to provide comprehensive ICT solutions for disaster response. These partners provide their subject matter expertise and help create specific applications on our technology platforms to mitigate or manage disasters as they occur. Influenza tracking, epidemiology-specific applications, and simulations around disasters or social distancing in pandemic environments are a critical part of what we are able to offer. Business continuity management is a huge component that companies look at and governments must take into consideration as well. Maintaining continuity in business is critical because they serve as the life blood of response efforts and the revitalization of a devastated community. Microsoft, along with our partners, provide technology solutions that insure critical systems, allow information flow to continue, and enable our impacted customers’ and partners’ systems to get back up and running quickly.

The second core service is global partnerships. We partner globally with lead non-government organizations or UN OCHA (The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Human Affairs), which leads information management for the UN. In addition to collaborating during active disaster responses, Microsoft has developed enduring partnerships with key government, IGO and NGO leaders in the disaster management arena to conduct Research and Development. To that end, the organizations provide subject matter expertise related to the field and their most vexing issues, while Microsoft works to determine how we can push the leading edge of technology to solve problems.

The last piece of our focus is around community involvement. We help Microsoft employees as well as citizens in the community become involved in assisting disaster response efforts in the ways that are most impactful. For example, we’ve just launched Vine. You may not be familiar with it, but it is our new social networking capability. Vine has huge implications in empowering individuals to communicate and work together, ultimately helping lead response organizations in emergency response efforts through the power of social networking. It links into Twitter, Facebook, instant messaging, and brings a lot of those pieces together from a public safety perspective.

SPhD: And we’ve seen recently with the Iran crisis and earthquakes that have happened, a lot of times in today’s day and age, information is leaking out through these social networking sites. And so it helps people to find each other, to get access to information, relatives know how their relatives are doing. And actually I feel very strongly about [this technology] because, for example in the city of Los Angeles, you have a lot of at-risk populations, in all big cities, like, say, older generations, immigrant populations, where second and third-generation relatives might be very savvy on how to use this technology, and they could relay information back to their family members that may not be fluent in English or may not know how to use a computer. But you can trickle that effect down to save lives and to keep people informed of what’s going on.

CB: One benefit of Microsoft Vine is understanding the scenario around that social networking connection; that not everyone is IT savvy. Vine actually allows the people that you know to select how who they want to receive information from you. If they don’t have a PC, you can send an alert and it will call their land line and use integrated voice response to say, “So-and-so is now in the hospital. They’ve had a cardiac arrest. They wanted to let you know you can contact me if you need anything. I’ll be calling back in one hour with an update.” Or “Can you pick up the kids? I’ve had to take them to the hospital.” Information can be received via PC, cell phone, IM, all of the above. Also [to self-select] based on the sense of urgency. If it’s not very urgent, just send me an email. If it’s a high level of urgency, hit ‘em all.

SPhD: How willing are these organizations to adapt to novel and evolving technologies?

CB: Very willing. We find that the NGOs very much understand the value of technology, primarily around situational awareness and collaboration. An NGO going into a response needs visibility into where the needs are, what issues are involved, and how they can map their assistance to those needs. It is also vital that response organizations have visibility into what others are doing to address these needs. Without the situational awareness and being able to collaborate with other relief agencies, many times what happens is one area gets a tremendous amount of attention, causing all of the NGOs to respond to the same area. There ends up being an overabundance of resources to service that population, meanwhile many communities are left underserviced and in need of food, water, and shelter. Without comprehensive awareness of what is going on, the distribution of relief goods cannot be as effective.

SPhD: Yeah, like when the 2004 tsunami hit, it seemed like the whole world descended on Thailand, but surely around the rest of the world—

CB: Sri Lanka, initially, was underserviced. Through these experiences organizations have gained an understanding of the value of those pieces. With an NGO, you’ll find that they don’t have a lot of overhead. They run on very small margins and so IT budget on the whole is incredibly small. And this is something that Microsoft has taken to heart, because while NGOs are often very receptive and looking at cutting-edge ways to use technology, they often can’t afford the IT infrastructure costs.

SPhD: That is such an interesting observation, because the scientists on the other side sometimes get very frustrated and they feel like [large NGOs and IGOs] don’t want to adapt to these technologies. They want to stick to the old way of doing things. But what you’re suggesting is that for them, the old way is the more economical way and they don’t have the resources to apply a new, snazzy technology.

CB: It can be very intimidating too. You have to migrate users, but you also have to migrate data and knowledge. That can seem like a very big hurdle, but Microsoft has made tremendous investments in NGOs groups that we’ve seen are very influential, including NetHope, a non-profit IT consortium of 26 different NGOs that focuses on solving their common challenges through collaboration and leveraging technology. Microsoft has invested $42 million dollars to help build their IT infrastructure so that these 26 NGOs can increase their technological capacity and develop solutions that may have otherwise been unattainable. We also work closely with organizations like TechSoup, through which to make our software and solutions available at nominal costs to the non-profit community.

SPhD: When you do work in places such as Africa or other developing countries where there might be a paucity of infrastructure or networks for modern technology, what are some of the challenges that you encounter?

CB: That’s a great question! Africa is a great example of that. Many of the natural disasters that we focus on, the majority of them happen in the Asian Pacific, or the highest probability [of occurrence is there] are in emerging or underdeveloped economies where you may not have the technology or the infrastructure needed to run robust applications. An area where Microsoft has spent a lot of time is in what we call “austere or complex environments” just like Sudan, Darfur, Afghanistan, Haiti, and taking a two-prong approach. You start working with partners like Cisco to optimize satellite routing capabilities, so you can share information in the Congo around an Ebola outbreak without being hampered by the lack of existing infrastructure. We also work on optimizing the use of handheld devices with Microsoft® Unified Communications software. This way even if I’m somewhere in the Congo, I can get enough bandwidth through a satellite and a handheld device to have a videoconference. It is also necessary to be able to parse data and break it up to send it through minimal bandwidth.

Another way that Microsoft is seeking to address technology deficits outside of the disaster response arena is through a program called Microsoft Unlimited Potential™. The goal of Unlimited Potential is to get accessibility to what we’d call the “base of the pyramid”. Many global studies conducted both externally and in the industry say, within the economic pyramid, you have 1 billion people in the U.S. and developed countries that have access to power, water, critical infrastructure and higher education. Then there’s the middle and bottom of the world economic pyramid, 5 billion people that do not yet have access to many of the core components. Unlimited Potential seeks to address the barriers to sustained social and economic development including: environmental or infrastructure obstacles, the need for personalized solutions, and the prohibitive cost of technology. It is an entire organization focused on developing on solutions for transforming education, fostering local innovation and enabling jobs and opportunities.

SPhD: And actually working with the local populations is going to be really important. Because often times, Western societies underestimate these people’s capacity for embracing [our technology or aid]. The best example that I can give from my own field is when HIV cocktail therapies first came out. One of the big resistance arguments to providing these widespread in Africa was, “Well, these people don’t tell time like we do, or they don’t have as modern of a medical system. They’re not going to know how to take them properly and they’re going to miss their doses.” Turns out that every major epidemiological study (as a recent example) shows that they’re actually more diligent (>90% diligence) about taking them in their proper dosage and at the proper time.

CB: What were the psychological roots that drove that?

SPhD: [Scientists conjecture] that adherence success is best explained as a means of fulfilling social responsibilities and thus preserving social capital in economic and cultural settings where good relationships are necessary for survival. In a recent expert commentary on the African HIV cocktail regimen epidemiology, Agnes Binagwaho and Niloo Ratnayake, discuss the importance of social capital in African societies compared to more developed countries, stating that “people in the US tend to be more individualistic and therefore less focused upon and connected to the group as a whole.” So this really shows that we can work together with people culturally to help them integrate [technology] how they know within their own vein and cultural and social mores.

CB: It’s going to be so important. Agreed.

SPhD: So I guess when it comes down to it, software technology is really the silent hero in a lot of these global disasters.

CB: Quickly to address the cultural piece, because I think that you’re right on, one of the things that Microsoft has done around those cultural sensitivities is to work with partners to develop a translator application. Translation capability is important for disaster response efforts because disasters are becoming more global in terms of response. Communicating quickly between languages when a speaker of the local language cannot be found to assist and being able to bring in a subject matter expert that is not fluent are critical to global responses. Technology can be used to overcome those barriers and there are applications that can be downloaded for free. Through instant messenger, I can type something in English and it will be translated directly from my real-time instant message to Mandarin [or any other language].

SPhD: Keeping it a bit current. Tell me about Microsoft’s recent work in the H1N1 pandemic breakout and your role in tracking the disease and working with public health infrastructure.

CB: Whenever we see a disaster occur, or a pending disaster coming like a hurricane, we have a standard operating procedure that the company goes into. Microsoft has 166 offices around the world and employees in many different locations. Any of those, if they are in an impacted area, or a potentially impacted area, immediately convert part-time to what is an extended Disaster Response team working in conjunction with our corporate team. We manage disasters as locally as possible, just as any standard police force, or emergency management agency does. For instance, as we started to see the influenza emerge in certain countries the corporate Disaster Response team connected immediately with our local subsidiary team who already had solid relationships with the government health officials through standard operating technology engagements. The Disaster Response team distributed a letter and reached out personally to the lead response organization to outline standard offerings and ways that Microsoft would be able to use our technology, partner assets and subject matter expertise to help manage the outbreak.

It was a very intensive four days, where Microsoft worked directly with the country’s lead response organization, their top advisors, and IT staff to assess the situation. The key factors to determining if a technology solution will be easily assimilated and adopted under any scenario are how the agency and the local culture currently deal with technology and the technology maturity level. Based upon these discussions, Microsoft built out two different websites, or what we call “portals”, for information sharing. One was a portal we built for the lead response agency to share information with ALL citizens about prevention, where to go for assistance, key contacts, plus updates around the current influenza cases and guidelines. This portal was built on Microsoft SharePoint technology. The other solution designed for this organization, was an inter-agency collaboration portal – a secure site for the national health organization to collaborate with local agencies throughout the country and to collect pandemic information regarding strain mutations, medical needs, hospital capacity, etc. This was a big step in enhancing situational awareness and enabling the lead response organization to coordinate resources across the country more effectively.

At the same time, we also worked with a major international health organization, to create a way in which that organization can actually work with governments around the world to collect data as the virus spreads, monitor potential mutation of the virus, and to understand what is happening in every country real-time. Our development teams worked with the global health agency to build the information collection and business intelligence engine and connected the aforementioned national response organization directly into it. The national response agency tool was the first pilot to start feeding information to the international health organization through joining the systems that we built for them.

[ScriptPhD note: Microsoft’s unified intelligence platform, Amalga™, was also used to build tracking applications for domestic hospitals seeking to track swine flu symptoms, manage patient lists, and efficiently parse through test results to follow up with any positive cases. See the article in InformationWeek here.]

SPhD: So you can truly say that Microsoft’s efforts [at the start of this pandemic] really helped contain this influenza virus. It’s not that big of a stretch to say that because of what you were able to do. Seriously, take a bow, that’s incredible!

CB: Thank you.

SPhD: In terms of you personally, where do you derive your biggest sense of satisfaction and victory in what you do?

CB: One point of satisfaction is evidence. Whether it was in China with the Sichuan earthquake, Myanmar with the cyclone, or H1N1 the immediate impact of the work we did and evidence that it helped save lives is what drives me. The ability to utilize our expertise and put technology into the hands of those who can truly make life better for others is incredibly fulfilling. We are able to have a direct impact on life safety and community resilience.

The other area of pride for me is giving our Microsoft employees and partners the opportunity to make a tremendous difference. Every time there is a natural disaster, I have an overwhelming number of our global partners as well as, many of the 100,000 Microsoft employees worldwide, calling me and my team to say, “I’m willing to do anything. Tell me how I can help.” These people continue with their day job[s], and will burn the midnight oil for seven days in a row if that is what it takes to do custom coding to build these applications. I’ll have people in India, Mexico, and Iceland all coming together to do distributed

development in a center where we’re building out these applications and hosting them for governments or for the UN. I’ve had them call and say, “That was exhausting, but you just allowed me to do what could be the most meaningful thing I’ve ever done for a community.” The people at Microsoft are that committed to making a difference. Giving them the opportunity to have such an impact and see the results of their hard work is very fulfilling. Our partners are incredible, the people at Microsoft are incredible, the passion and the intellect. It’s amazing.

SPhD: Biggest sense of frustration?

CB: The biggest thing I would like to see is more time spent on preparedness and recovery. There is always a lot of focus on response efforts, but there is not the time that myself and many public and private agency sectors would like to see on the preparedness and recovery pillars. That is where the resiliency really comes in. So much more could be done to mitigate consequences and more lives could be saved up front if we could spend as much time and effort on preparedness. I have seen this begin to change in the last few years, but there is still a lot of room for improvement.

On the recovery side the focus should be on learning and strategically rebuilding an economy or a community to the next level so that not only are they better sustained for the next [disaster], but their lives are better. Some of the key considerations for this in recovery are bringing closer education streams, building a more robust infrastructure, bringing internet in, or having early warning systems and procedures in place. For example, if an early warning system was in place for the 2004 India Ocean tsunami, so much could have been done within that four-hour window.

SPhD: Or if we had stockpiles of certain medicines so that we didn’t have to wait until emergencies hit. Or even on a local community level, I was at a[n emergency preparedness] talk where somebody said, “You know, one of the simplest things people are gonna fight over if we have a bad emergency in America is food and water.” We don’t stockpile food and water supplies for ourselves. So it’s very simple things. I’m going to applaud you big time on that response, because that is one my personal pet issues—

CB: Good, start blogging! Put it out there!

SPhD: —preparedness is so important. So I’m just going to give you a big, fat ScriptPhD gold star for that response! A couple of extended idea questions. What do you see as the ultimate role of tech companies extended across the spectrum (Apple, Microsoft, Google, etc) in modern development, global health and disaster relief?

CB: Another reason why I love this space, is when it comes to corporate social responsibility a lot of the competitive boundaries really do fall down. The number of private sector companies assisting with disaster response, health issues, and pandemics is tremendous. It will be important to grow public-private sector partnerships because there is so much to be gained by the resources and the subject matter expertise private sector companies can provide to bolster the response capabilities of the public sector. There’s been a lot of work and policy development done over the past few years to address how we align and collaborate more effectively within public-private sector partnerships. It has been a real learning experience. We are starting to see IT companies and health industry companies come together around the importance of establishing relationships and policies ahead of time so that private sector resources can more easily be utilized by the public sector in times of disaster. There are a lot of things that happen throughout the year where you will get Microsoft and Cisco and Apple and Google and IBM all sitting in a room with a health agency or a key government, saying, “How can we bring our technologies together to help solve this issue?”

SPhD: Put your egos aside, this is no longer about me, myself and I, it’s about banding this technology synergistically to help people.

CB: Very much! Exactly. And you really see a lot of that in this space [disaster relief and aid].

SPhD: Notwithstanding the idea that we can, and do, approach many of these problems concomitantly, suppose that I came to you today and I said, “Claire, I’m going to give you a magic wand, and will allow you, based on everything you’ve seen and participated in, to get rid of one of the world’s major myriad of problems, be it some sort of discord, or a looming public health catastrophe, or whatever you want.” Which global catastrophe, threat or disaster would you eradicate and why?

CB: Rather than simply saying “I’d get rid of H1N1”, I would prefer eliminating a root cause of something. And that root cause has more to do with a human or a psychological aspect around collaboration and information sharing. There are many human examples of drivers behind why Ebola or avian flu continues to be problematic, but resistance to sharing data and collaborating for joint solutions has a significant impact on the continued spread. We have so many political, social, and cultural boundaries. Wiping away those obstacles, I think, would have major repercussions across many of types of disasters.

ScriptPhD.com would like to extend a heartfelt thanks to Claire Bonilla for providing her time and thoughts, and to Microsoft for their hospitality in hosting us. More information about the Disaster Response program, as well as a comprehensive overview of the rest of Microsoft’s humanitarian relief efforts, is available at their official site and in a recent FEMA interview with Claire Bonilla.

~*ScriptPhD*~

***************

Follow ScriptPhD.com on Twitter and our Facebook page.