We have truly saved the best for last! ScriptPhD.com’s coverage of the 2010 World Science Festival in New York City concludes with panels ranging from the secrets hidden in our underwater oceanic wonderland (especially apt as we clean the worst oil spill in history), a panel on the hidden dimensions of our visual world, and a behavioral panel that sheds light into how animals and humans process thought. In addition, we provide a short video of star-gazing New Yorkers who came out to see the James Webb telescope last week. Our correspondents were the amazing New York City science writers Jessica Stuart and Emily Elert. Synopses and pictures of three extraordinary panels with the premier scientists of our time under the “continue reading” cut.

ILLUMINATING THE ABYSS: The Unknown Oceans — June 5, 2010

Under our oceans lie mountains many times higher than the Alps, valleys far wider than the Grand Canyon, countless volcanoes, and the largest waterfall in the world. There are thousands of species down there – the current known number is estimated to be around 230,000, but it could be as many as three times that, according to the Census of Marine Life. The oceans drive our climate and weather, and generate nearly 70% of the oxygen in our air. The one thing that life cannot exist without is water, and yet, we treat our oceans “like an infinite resource and a garbage can.”

A packed house gathered Saturday afternoon at the Paley Center for Media, for the panel Illuminating the Abyss: The Unknown Ocean. Jacques Cousteau’s grandson, Fabien Cousteau, a passionate ocean explorer in his own right, along with scientists Sylvia Earle, David G. Gallo, and David E. Guggenheim were the panelists, with moderator Bill Weir. Though the topics were diverse, ranging from the oil spill to personal submarine devices to unsustainable fisheries, all reverted back to the fact that we have so much left to learn about our oceans, and are destroying them more and more each day.

The presentation started with a tribute to Jacques Cousteau, perhaps the most famous explorer of our oceans. His films and adventures have inspired generations to take to the oceans to try to learn and preserve this most unique ecosystem. Unfortunately, this research is woefully underfunded – in the last 50 years, we’ve sent 12 men to the moon, but only 2 to the deepest reaches of the ocean. This lack of knowledge about the conditions and ecosystem in our waters is a big problem, especially given the current state of affairs in the Gulf of Mexico. As of Saturday, almost two million gallons of chemicals had been dumped in the Gulf to try to disperse the Deepwater Horizon spill. Earle called this action appalling, saying we “should not be pouring toxic chemicals into the sea without knowing the consequences.”

Guggenheim is also distraught by the spill. He studies the coral reefs in Cuba – nearly pristine reefs, with healthy ecosystems, that researchers were hoping would give us clues into why so many other coral reefs around the world are dying. Now, with the oil headed that way, they may not get the answers they’re looking for. Enough damage will be done in the Gulf alone, but if the Gulf Stream picks up the oil and circulates it down past the Cuban reefs, then up along the Atlantic coast and over to Europe, we’re looking at a problem of such magnitude that we won’t even know the full impact for many years.

Aside from the tragedy of the oil spill, we do constant damage to our waters through unsustainable fishing. Earle maintains that there is no such thing as “sustainable” commercial fishing. Guggenheim pointed out that we “manage” our fisheries as if they’re crops, like corn, that just grow each year, and we continue to harvest in greater numbers than the sea can replenish. There are proposals in the works to create AquaCulture – land based systems that could create a sustainable industry. Systems are already working in Asia, Australia, and Europe, and could be beneficial in areas like the Gulf, providing jobs and a big investment for the future to those who make their lives in the now decimated fishing industry. Aside from that, we have to start managing our oceans as an entire ecosystem, not as unrelated species that we just pluck out of the water and put on our plates. We don’t fully understand how everything is connected, but we know that if we continue to eat the large predators, like tuna and sharks, we’re creating an untenable long-term situation.

Fabien Cousteau said it best, succinctly reminding us that “There is no Planet B.”

To preserve our oceans, we must first learn more about them in-depth. To learn more, visit:

Mission Blue

Plant A Fish

Ocean Doctor

In addition to our written coverage of the 2010 World Science Festival, ScriptPhD.com took to the streets of New York City with a camera at the star-gazing event in Bryant Park last week. Dozens of amateur star-gazers gathered around the James Webb telescope on display, and we caught up with them to talk about what astronomy meant to them and why they were there. For a genuine feel of the Science Festival vibe, take a look at this video by Jessica Stuart:

Jessica Stuart is a writer, photographer and videographer living in New York City. Find her on her personal blog, and Twitter.

HIDDEN DIMENSIONS — June 5, 2010

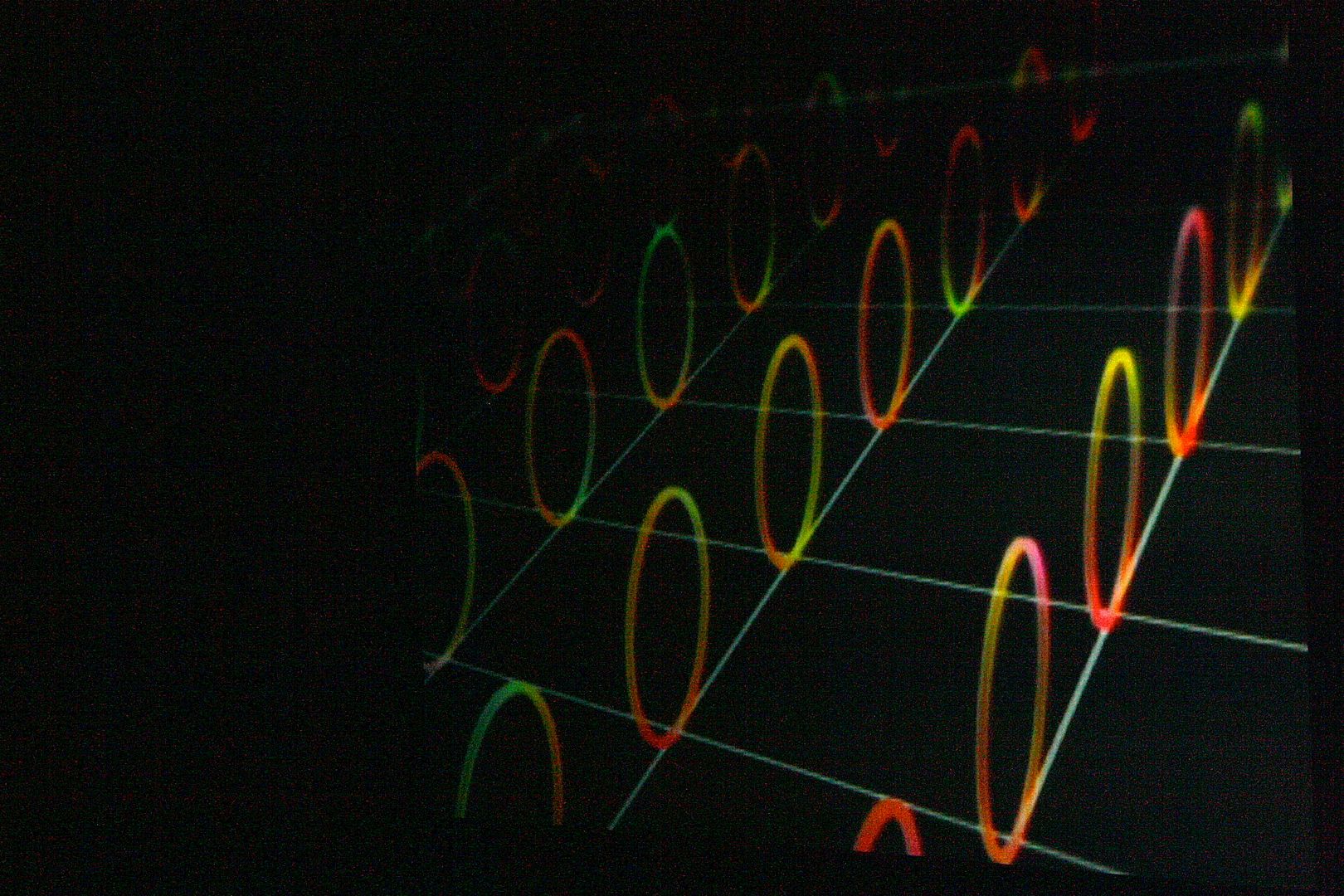

“This is really about going beyond our senses,” said Brian Greene from the stage at “Hidden Dimensions,” an event at the World Science Festival Saturday night. The screen behind him (picture below) showed a grid of fluorescent lines with loops sitting on top, like rings balancing on a checkered table. The grid represented all of the dimensions we are aware of—the three that make up space, plus time—and the rings represented another, theoretical dimension.

This extra dimension is just one of six or seven that physicists like Greene think exist, though they are too small to be seen or directly detected by scientific instruments. The extra dimensions are a part of string theory, a mathematical idea that unites two conflicting branches of physics—general relativity and quantum mechanics—by proposing that the tiny particles in the universe are all part of miniscule, vibrating strings.

It sounds crazy. But then, so do a lot of things we can’t see or touch or hear. As an example, Greene showed an animation of a flat plane with a cube passing through it. If you lived only on that flat plane, you would see a shape-shifting shadow—a triangle that grows, becomes a square, and shrinks back into a triangle. It would be hard to make sense of, in a flat world, but adding another dimension—in this case, a third dimension, makes the whole picture a lot clearer. But “adding another dimension” to the way we understand the universe is not such an easy thing. Our fourth dimension, time, has been around for a while, but most of us still get a brain-ache from trying to understand what “space-time” actually refers to, or imagining the inside of a black hole.

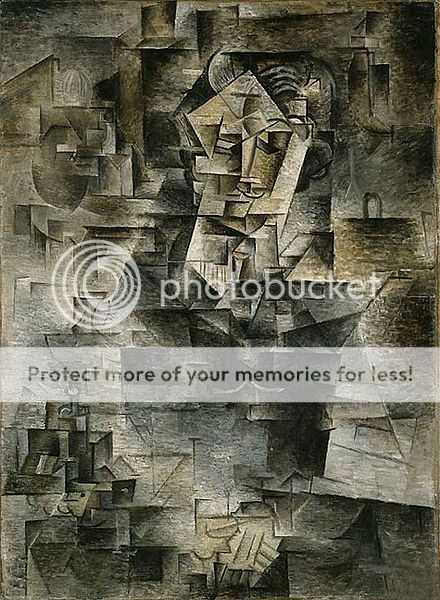

Linda Henderson, an expert in twentieth-century art who was on the panel Saturday night, pointed out that, when this mysterious fourth dimension first came around in the late 19th century, the concept influenced movements in art and literature. Cubism, she said, is a good example of artists grappling with a new concept. Paintings like Picasso’s “Portrait of D.H. Kahnweiler” demonstrate these artistic wanderings into the new dimension. Though the painting is abstract, it represents a real idea. “It’s a painting that we can’t really say is only three dimensional,” Henderson said.

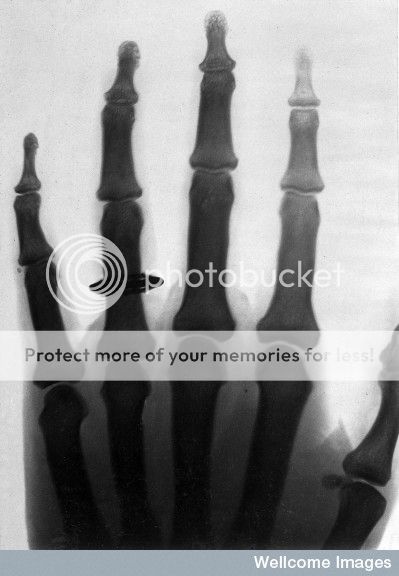

The invention of the x-ray machine, said Henderson, served as another reminder of the limits of our own senses. Displaying an early x-ray photograph on the screen, Henderson asked, “who can say there isn’t a fourth dimension, just because you can’t see it?”

But Lawrence Krauss, a physicist also sitting on the panel, reminded the audience that ideas in math and art are different from science. “People want there to be more there than meets the eye,” said Krauss. While art and math can explore these ideas, Krauss noted, “there’s a huge difference between math and physics.” In other words, physics—like all science—requires theories to make testable predictions about the world, a hurdle string theory has yet to clear. Krauss recalled the words of Richard Feynman, one of the world’s most beloved physicists: “Science is imagination in a straightjacket.”

The challenge for physicists is to find a straightjacket big enough for string theory. In the meantime, we always have art.

ALL CREATURES, GREAT AND SMART — June 5, 2010

There were five panelists on stage at “All Creatures Great and Smart,” an event at the World Science Festival on Saturday afternoon, and each of them presented ideas that blur the clean lines people have tried to draw between the human and animal mind.

But it was panelists six through nine, with the help of number five, Brian Hare, who stole the show. Hare, an anthropologist, is interested in whether animals can develop theory of mind, the ability to think about what others are thinking about (otherwise known as the “I know you know that I know you know” phenomenon).

Humans aren’t born with theory of mind, but they develop it at a very young age, said Hare. “By the time your kid is four, they’re very good at deceiving you,” a clear sign that they can think about which facts you may be keen to—and which you may not be.

As a graduate student, Hare performed an experiment with chimpanzees, using the same type of test used by child psychologists. He put two containers upside-down on the floor in front of each chimp, hid food under one (children get toys), and then signaled the food’s whereabouts by pointing, standing closer to one bucket than the other, etc.

The chimps did not take the hint. They did not, it seems, have theory of mind.

Then, Hare began to think about how good his dog was at following social cues (and using them to its advantage), and decided to try the same experiment with dogs. His advisor was at first skeptical. “He said, yeah, yeah, everyone’s dog does calculus,” Hare remembered. But Hare ended up conducting his experiment, and on stage at the World Science Festival, he offered to repeat it with four volunteers. The first three dogs, Bela, Sammy, and Molly, were angelic subjects; they sat upon instruction, and awaited permission to retrieve a piece of cheese that Hare laid down a few feet away.

And when Hare put a piece of cheese under one of the buckets and then pointed to it, the dogs followed the cue immediately.

This spotless confirmation of Hare’s canine-theory-of-mind was tarnished, however, by the fourth subject, a spirited Burmese Mountain dog named Georgie. It wasn’t that she couldn’t follow cues—she simply took a first-come, first-serve approach to the treats, preventing Hare from testing his hypothesis. As Georgie’s owner pulled the reluctant pet from the stage (she wanted to stay with the cheese), Hare pointed out that Georgie had gotten everything she wanted while on stage.

Which, at the end of a show about how animals are like humans, left me wondering how much humans may be like animals: are we all either blunt or clever?

Emily Elert is a freelance science writer living in New York City. Follow her on Twitter.

Follow the World Science Festival on Facebook and Twitter. All photography ©ScriptPhD.com. Please do not use without permission and credit.

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development.

Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

]]>

ScriptPhD.com’s coverage of the World Science Festival in New York City continues towards the physics and mathematics realm. Day 3 events on Friday included an intimate discussion about astrophysics and the new James Webb Telescope, set to replace Hubble in June of 2014, a panel about hearing and visualizing gravity with Albert Einstein’s modern successors, and a panel about the very limits of our understanding of science—the line between what we do and don’t (or can’t) know—and its bridge to culture and art. Contributions to our coverage were done by New York City science writers Jessica Stuart and Emily Elert. Synopses and pictures of three extraordinary panels with the premier scientists of our time under the “continue reading” cut.

FROM THE CITY TO THE STARS: Star-gazing with the Webb Telescope — June 4, 2004

It was a cloudy night in Manhattan, but the dozens of amateur astronomers and spectators who came down to Battery Park didn’t seem to mind. People from all over the tri-state area brought out their telescopes, ranging from under a foot to over 7 feet long, in hopes of seeing Saturn and with luck, some other planets. Many came early in the day to set up, happy to talk to visitors about their interest in the cosmos. As the sun started to set, Dr. John Mather, Dr. John Grunsfeld, Dr Heidi Hammel, and moderator Miles O’Brien sat down to talk with about the James Webb Space Telescope and space in general. Acknowledging all of the amateur astronomers in the audience, they pointed out that in 1994, you needed the Hubble Telescope to see many of the things that their personal telescopes set up in the park could see on a clear dark night from anywhere.

O’Brien brought out a laser pointer, and Dr. Mather explained in detail all of the parts of the full-scale model of the James Webb Space Telescope that was set up nearby. He explained how, because of its size and the rocket that it will go to space on, it will launch folded up, and then deploy itself in space. Its final destination is a million miles from the earth, at a Lagrange point, where it will be stable. There will be no repair missions to the Webb Telescope, as there have been to the Hubble, which is in orbit 300 miles from earth. Dr. Grunsfeld was on three of the five repair missions to Hubble, and spoke of how amazing it was to see Neptune from that vantage point.

Audience Q&A ranged from life on other planets, the end of space, and how black holes work. The scientists were dynamic and engaging, doing their best to answer all of the questions. Fortunately, cloud cover didn’t matter and telescopes weren’t need to see the star that much of the audience was interested in. At the end of the panel discussion, Astrophysicist, Director of the Hayden Planetarium, and NOVA host Neil deGrasse Tyson took the stage. He was supposed to kick off the star-gazing, but without much to see in the sky, he entertained the audience with more stories and facts about astronomy and science. Kids (and several adults), moved up to sit in the grass in front of the stage, to better hear and see this very animated legend.

Tyson grew up in the Bronx, and as a child, knew the nine stars he could see in the night sky. He admitted that even now, when he’s out of the city and can see a sky full of stars, he thinks “this is just like the Hayden Planetarium,” the first place he learned of the thousands of stars that could be seen with the naked eye. Even though he has the opportunity to use any manner of professional telescope out there, he praised the amateur astronomers for their interest and passion.

After the talk concluded, and the telescope owners and part of the crowd dispersed to try to star-gaze, a child who didn’t get called on approached the stage to ask Tyson his question. This turned into an impromptu sit-down session, with a large crowd gathering around. Tyson enthusiastically obliged, engaging the fans, especially the children who clamored to ask all manner of questions, wondering how black holes work, if there’s mass in space, and where Tyson got his hat. As the crowd grew, a microphone was brought back out, and those who stuck around were treated to an intimate audience with one of the best known astrophysicists in the country.

As the evening grew late, the clouds started to part, and the astronomers tried to find objects in the sky and on the tops of nearby buildings for the visitors to see. Despite the low visibility, everyone left happy, excited to have been a part of a wonderful evening in the park.

The James Webb Space Telescope is on display through Sunday, June 6, at 6pm, at Battery Park. Admission is free.

Jessica Stuart is a writer, photographer and videographer living in New York City. Find her on her personal blog, and Twitter.

ASTRONOMY’S NEW MESSENGERS — June 4, 2010

Marcia Bartusiak, the moderator at Friday night’s World Science Festival event Einstein’s New Messengers, walked on stage to a peculiar soundtrack. It wasn’t music at all, but a sharp thumping sound that started out in slow beats and, over the course of several seconds, progressed to a high-pitch whir like a baseball card in the spokes of bicycle wheel, before going out in an undignified “POP.”

It may not be beautiful, but it’s a sound physicists at the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) are dying to hear—gravitational waves, emanating from colliding, super-massive black holes like ripples spreading out through a pond. “In a way, our universe has been like a silent movie,” said Bartusiak. “Gravitational waves are going to turn us into talkies.”

Gravitational waves aren’t actually sound waves—they are ripples in space-time, oscillations in the very fabric of the cosmos, caused by the movements of massive objects. The waves were predicted by Einstein’s general theory of relativity, but they have never been directly detected. That is, until…

Until soon, physicists hope. Among the most hopeful, to be sure, is Rainer Weiss, a member of Friday’s panel and the inventor of the massive experiment designed to detect them. The experiment, currently operating at five locations on earth, involves splitting a beam of light through the L-shaped, four-kilometer-long arms of an interferometer. If a gravitational wave passes through, one of the beams of light will be stretched while the other is squeezed, resulting in a tiny, eentsy, weensty difference in the amount of time it takes the light to bounce back to the middle.

Why are eight kilometers of laser necessary to detect a wiggle the size of the nucleus of a hydrogen atom? “The smaller the thing we’re trying to detect, the bigger the experiment we need to do it,” joked Kip Thorne, a theoretical physicist on the panel (and one of the world’s best experts on gravity).

On stage, Thorne and Weiss kept up a lively, good-natured banter over the merits of theory versus experimentation, while Andrea Lommen, an observational astronomer, talked about her preferred method of seeking out gravitational waves—by looking for small fluctuations in the energy emitted from pulsars. “Pulsars are my detectors,” she said. “I already have this galactic-scale detector that’s been given to me by the universe.”

Whatever their method, the three scientists are all hoping that the information riding in those elusive waves will allow them to gain insight into the remotest, strangest parts of the universe—from the formation of galaxies to time-creeping depths of black holes.

THE LIMITS OF UNDERSTANDING — June 4, 2010

One of the greatest public misconceptions about science, reinforced by our years of schooling and fat, glossy textbooks full of facts, is that it deals with stuff we already know about our world, when in fact all of science takes place at the boundary between what we know and what we don’t. And no one seems more aware of this than the panelists at Friday’s event The Limits of Our Understanding, at the World Science Festival.

The basis of the panel discussion was the idea of mathematical uncertainty or, more precisely, Godel’s incompleteness theorem, proposed in 1931, which says that it’s impossible to prove or disprove all of the parts of any formal system. “Eighty years later, we still don’t understand what Godel proved,” joked Gregory Chaitin, a mathematician and computer scientist. Then he added, more seriously, “the fallout hasn’t stopped.”

Perhaps, “the fallout” from Godel’s incompleteness theorem isn’t a semi-new phenomenon, but a problem that humans have been grappling with since the beginning of human thought. Mario Livio, an astrophysicist, compared it to Plato’s cave allegory, where the workings of the universe are played out by a fire in a cave, but we can only see the shadows cast on the wall. Are we describing the world as it really is, or only as we perceive it to be, with the fierce limitations of our senses?

And if we had other senses, Livio asked, and a different experience of the world—if, for example, we were jellyfishes living at the bottom of the Pacific Ocean, would we have invented arithmetic and geometry? Or what if our senses were simply altered? “If we saw in infrared, we might not have shapes,” he suggested. “It’s an artifact of our sense perceptions.”

“This is where absolute truth is gone!” cried Chaitin. “It’s gone nowadays—it’s out of fashion. But it’s still important to think about, because it might come back!”

Along with the argument about absolute and relative truth, the panel discussion ranged somewhat freely between each of the panelist’s subjects of interest—Rebecca Goldstein, a philosopher and novelist, brought up the question of consciousness, and suggested that the body of facts relating each of us to the natural world does not, in sum, add up to a complete description of the human experience.

Marvin Minksy, a cognitive scientists, disagreed. “Consciousness is just a bunch of different problems dumped into the same trash basket,” he contended. He pointed out that Galileo used the same word for velocity and momentum in his math, and the problem seemed like a very complicated one until someone came along and separated them into two different variables.

But along with this ardently demystifying view of human experience, and the somewhat depressing notion that the universe as we understand it is a mere matter of the tuning of our senses, Minsky gave us all a pretty good argument for showing up. “A molecule of DNA is stable room temperature for one billion years,” he said, but evolution itself is a random thing.

“Evolution remembers what works, but it doesn’t remember the ones that died.” It’s important for us to keep this in mind, he said, because it’s up to us to remember what works and what doesn’t—it’s up to us to transmit knowledge through time.

“Without culture,” Minsky said, “we don’t survive.”

Emily Elert is a freelance science writer living in New York City. Follow her on Twitter.

Follow the World Science Festival on Facebook and Twitter. All photography ©ScriptPhD.com. Please do not use without permission.

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development.

Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

]]>