How many times have you said to yourself, “If only I didn’t have to sleep.” Or “If only I tap into my brain’s full neuronal capacity, imagine the things I could do?” Such neurocognitive superpowers would seem to be the stuff of science fiction…for now. In the new film “Limitless,” these wishes unexpectedly come true for a struggling writer, but the results—and unexpected side effects—cause him to wonder whether it was all worth it. Sleek, stylish, sexy and well-crafted, “Limitless” is part scientific inquiry into the limits of expanding the pharmacopeia beyond current human capacities and part thriller to see if the main character who dares to try will get away with it. ScriptPhD.com’s full review of Limitless under the “continue reading” cut.

REVIEW: Limitless

ScriptPhD.com Grade: B+

“What kind of a guy without a drug or alcohol problem looks like this?” ponders a disheveled, unkempt Eddie Morra (Bradley Cooper) in the new film “Limitless.” Since he’s obviously never met a scientist desperate to publish, he self-responds: a writer. Mired in writer’s block with a looming book contract, living in a New York City rat hole, and dumped by his successful bankroller/girlfriend (Abbie Cornish), Morra is a prototype of every hard-up creative in the absolute nadir of his or her career.

Seemingly by chance, Morra bumps into his ex-brother-in-law Vernon (Johnny Whitworth), a former drug dealer now “consulting” for a pharmaceutical company. He promises Eddie salvation for all his troubles—NZT48, a new miracle drug under development and clinical trial that activates special brain receptors and circuitry to achieve 100% neuronal function. A desperate Eddie takes the chance. Through some very clever color cinematography, the moviegoer takes part in Eddie’s miracle; 12 hours later, he’s written half his book, cleaned out his apartment, and gotten back in the good graces of his landlord. He is a new person.

Craving more of his creative panacea, Eddie seeks Vernon out, to discover that not only is NZT48 not FDA approved, but is being dealt illegally, something that ultimately costs Vernon his life. Now the sole proprietor of an entire stash of NZT48, Eddie becomes the king of the world. He reads books in hours, learns languages and instruments in days, makes millions in the stock market, and becomes an expert of multiple specialties within weeks. His life is limitless. If all of this seems too good to be true, it is.

With his stash dwindling, Eddie begins to experience side effects—headaches, nausea, vomiting, losses of chunks of time—and needs more and more NZT48 to function at full capacity. He is dismayed to learn that all of the NZT48 users in Vernon’s address book, which includes his ex-wife (Anna Friel), are either dead, dying or ruined. To top it off, Eddie is now deeply ensconced in a financial trading company, with his new boss Carl Van Loon (Robert De Niro) attempting to broker the biggest merger in corporate history. Leslie Dixon’s clever screenplay, based on the novel “The Dark Fields” by Alan Glynn, complicates the science plot with assassination attempts, murder charges, and a layered group of shady characters, all of whom become intertwined with NZT48.

The basic idea of medical science bestowing us with ‘limitless’ brainpower isn’t all that crazy, according to University of Minnesota physics professor James Kakalios, author of “The Physics of Superheroes” and “The Amazing Story of Quantum Mechanics.” In fact, drugs like Prozac and other SSRI inhibitors actively function by changing the brain’s basic electrochemistry. While it is not true that we only use 10-20% of our brains (we use all of it at different times), it’s only a matter of time before scientific understanding of neurochemistry might outpace the ethical morass of whether such enhancement is appropriate or worth the ensuing side effects, a theme that “Limitless” explores quite well.

The physical deterioration that Eddie experiences is quite possible, but Kakalios suggests that in real life, his character might even end up dumber than he started with a very rapid withdrawal. Without revealing the surprise ending, suffice it to say, NZT48 definitely leaves Eddie’s brain permanently altered. And this clever movie will leave viewers with lots of food for thought.

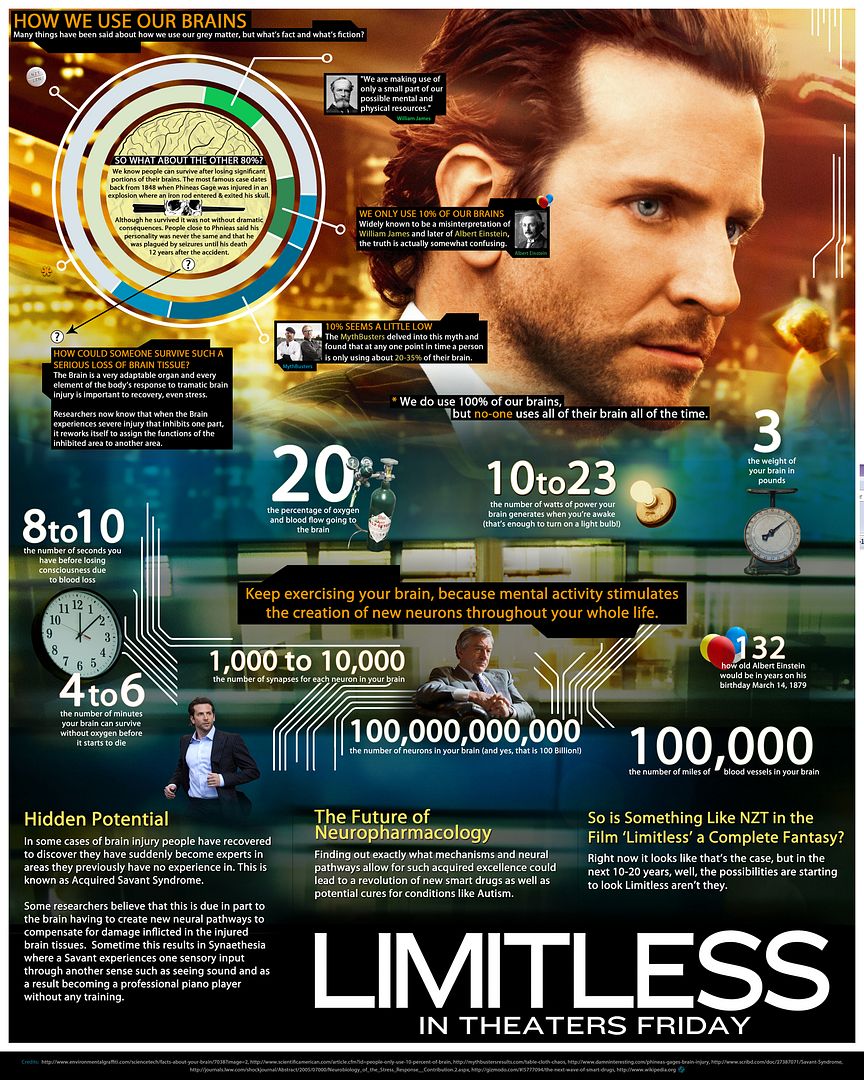

Relativity Media has put together a very interesting, clever infographic detailing some key facts about the human brain, its capacities and limitations, and the possibilities of future development of the fictional neuroactivating drug portrayed in the film:

Official Trailer:

Limitless goes into wide theatrical release on Friday, March 18, 2011.

~*ScriptPhD*~

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development.

Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

]]>

One of the most captivating books of 2010 was not a gory science-fiction thriller or a gripping end-of-the world page-turner, though its subject matter is equally engrossing and out of the ordinary. It is about somewhat crazy people doing crazy things as seen through the lenses of the man that has been treating them for decades. The Naked Lady Who Stood On Her Head is the first psych ward memoir, a tale of a curious doctor/scientist and his most extreme, bizarre, and sometimes touching cases from the nation’s most prestigious neurology centers and universities. Included in ScriptPhD.com’s review is a podcast interview with Dr. Small, as well as the opportunity to win a free autographed copy of his book. Our end-of-the year science library pick is under the “continue reading” cut.

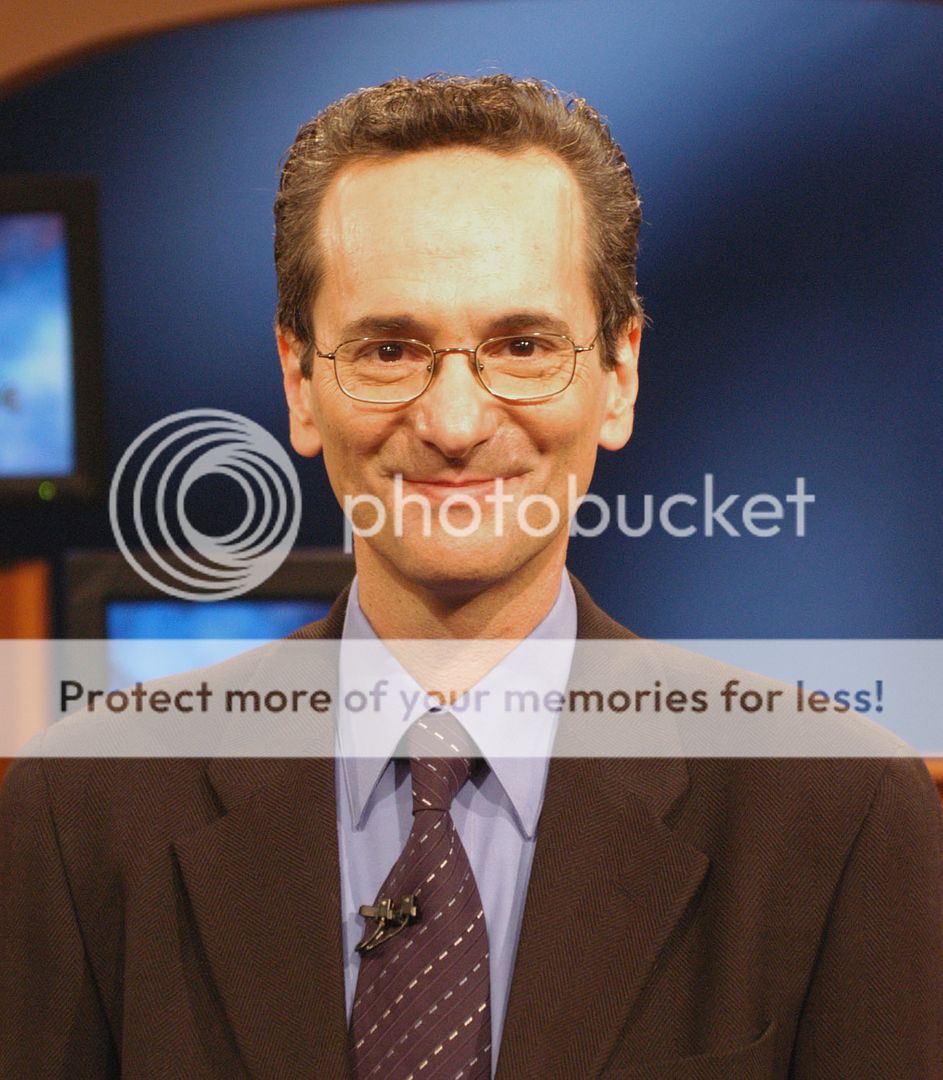

Gary Small is a very unlikely candidate for the chaos that many of us confuse with a psych ward. Whether it was the frantic psych consults on ER or fond remembrance of Jack Nicholson and his cohorts in One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest, most of us have a natural association of psychiatry with insanity or pandemonium. Meeting Dr. Small in real life is the antithesis of these scenarios. Warm, welcoming, serene and genuinely affable, his voice translates directly from the pages of his latest book. Told in chronological order—starting with

a young, curious, inexperienced intern at Harvard’s Massachussetts General Hospital to his tenure as a world-renowned neuroscientist at UCLA—The Naked Lady Who Stood On Her Head feels like an enormous learning and growing experience for Dr. Small, his patients, and the reader.

The scene plays out like a standard medical drama or movie. In the beginning, the young, bright-eyed, bushy-tailed, trepidatious doctor is exploring while learning the ropes on duty. There is, in the self-titled chapter, literally a naked lady standing on her head in the middle of a Boston psych ward. Dr. Small is the only doctor that can cure her baffling ailment, but in doing so, only begins to peel away at what is really troubling her. There is a bevvy of inexplicable fainting schoolgirls afflicting the Boston suburbs. Only through a fresh pair of eager eyes is the root cause attained, a cause that to this day sets the standard for mass hysteria treatment nationwide. And there is a mute hip painter from Venice beach, immobile for weeks until Small, fighting the rigid senior attendings, gets to the unlikely diagnosis. As the book, and Dr. Small’s career, flourishes, we meet a WebMD mom, a young man literally blinded by his family’s pressure, a man whose fiancé’s obsession with Disney characters resurfaces a painful childhood secret, and Dr. Small’s touching story of having to watch as the mentor he introduced at the book’s beginning hires him as a therapist so that he can diagnose his teacher’s dementia. Ultimately, all of the characters of The Naked Lady Who Stood on Her Head, and Dr. Small’s dedication and respect, have a common thread. They are real, they are diverse, and they are us. Psych patients are not one-dimensional figments of a screenwriter’s imagination. They are the brother who has childhood trauma, the friend with a dysfunctional or abusive family, the husband or wife with a rare genetic predisposition, and all of us are but one degree away from the abnormal behavior that these conditions can ignite. In his book, Dr. Small has pulled back the curtain of a notoriously secretive and mysterious field. It’s a riveting reveal, and absolutely worth an appointment. The Naked Lady Who Stood On Her Head has been optioned by 20th Century Fox, and may be coming to your televisions soon!

Podcast Interview

In addition to his latest novel, Gary Small is the author of the best-selling global phenomenon The Memory Bible: An Innovative Strategy For Keeping Your Brain Young and a regular contributor to The Huffington Post (several excellent recent articles can be found here and here). His seminal research on Alzheimer’s disease, aging and brain training has appeared in recent articles in NPR and Newsweek. A seminal brain imaging study recently completed in his laboratory garnered worldwide media attention for suggesting that Google searching can stimulate the brain and literally keep aging brains agile. Dr. Small regularly updates his research and musings on his personal blog.

ScriptPhD.com sat down for a one-on-one podcast with Dr. Small and discussed inspiration for the book, and how it conveys the inner thought process of a psychiatrist through their many interesting cases. In our podcast, we discuss how media and on-screen portrayal of psychiatrists contribute to people’s perceptions of the field, how the themes of empathy and humanity are indellibly woven into case studies, the challenges and fullfillment of psychiatry and the contribution of pop culture in modern psychoses.

~*ScriptPhD*~

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development. Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

Each of the brain’s 100 billion neurons has somewhere in the realm of 7,000 connections to other neurons, creating a tangled roadmap of about 700 trillion possible turns. But thinking of the brain as roads makes it sound very fixed—you know, pavement, and rebar, and steel girders and all. But the opposite is true: at work in our brains are never-sleeping teams of Fraggles and Doozers who rip apart the roads, build new ones, and are constantly at work retooling the brain’s intersections. This study of Fraggles and Doozers is the booming field of neuroplasticity: how the basic architecture of the brain changes over time. Scientist, neuro math geek, Science Channel personality and accomplished author Garth Sundem writes for ScriptPhD.com about the phenomenon of brain training and memory.

Certainly the brain is plastic—the gray matter you wake up with is not the stuff you take to sleep at night. But what changes the brain? How do the Fraggles know what to rip apart and how do the Doozers know what to build? Part of the answer lies in a simple idea: neurons that fire together, wire together. This is an integral part of the process we call learning. When you have a thought or perform a task, a car leaves point A in your brain and travels to point B. The first time you do something, the route from point A to B might be circuitous and the car might take wrong turns, but the more the car travels this same route, the more efficient the pathway becomes. Your brain learns to more efficiently pass this information through its neural net.

A simple example of this “firing together is wiring together” is seen in the infant hippocampus. The hippocampus packages memories for storage deeper in the brain: an experience goes in and a bundle comes out. I think of it like the pegboard at the Seattle Science Center: you drop a bouncy ball in the top and it ricochets down through the matrix of pegs until exiting a slot at the bottom. In the hippocampus, it’s a defined path: you drop an experience in slot number 5,678,284 and

it comes out exit number 1,274,986. How does the hippocampus possibly know which entrance leads to which exit? It wires itself by trial and error (oversimplification alert…but you get the point). Infants constantly fire test balls through the matrix and ones that reach a worthwhile endpoint reinforce worthwhile pathways. These neurons fire together, wire together, and eventually the hippocampus becomes efficient. It’s just that easy. (And because it’s so easy, researchers aren’t far away from creating an artificial hippocampus.)

Now let’s think about Sudoku. The first time you discover which missing numbers go in which empty boxes, you do so inefficiently. But over time, you get better at it. You learn tricks. You start to see patterns. You develop a workflow. And practice creates efficiency in your brain as neurons create the connections necessary for the quick processing of Sudoku. This is true of any puzzle: your plastic brain changes its basic architecture to allow you to complete subsequent puzzles more efficiently. Okay, that’s great and all, but studies are finding that the vast majority of brain-training attempts don’t generalize to overall intelligence. In other words, by doing Sudoku, you only get better at Sudoku. This might gain you street cred in certain circles, but it doesn’t necessarily make you smarter. Unfortunately, the same is true of puzzle regiments: you get better at the puzzles, but you don’t necessarily get smarter in a general way.

That said, one type of puzzle offers some hope: the crossword. In fact, researchers at Wake Forest University suggest that crossword puzzles strengthen the brain (even in later years) the same way that lifting weights can increase muscle strength. Still, it remains true that doing the crossword only reinforces the mechanism needed to do the crossword. But the crossword uses a very specific mechanism: it forces you to pull a range of facts from deep within your brain into your working memory. This is a nice thing to get better at. Think about it: there are few tasks that don’t require some sort of recall, be it of facts or experiences. And so training a nimble working memory through crosswords seems a more promising regiment than other single type of brain training exercise.

This is borne out by research. A Columbia University study published in 2008 found that training working memory increased overall fluid intelligence. So the answer to this article’s title question is yes, brain training is very real. (Only, there’s lot of schlock out there.) But hidden in this article lies the new key that many researchers hope will point the way to brain training of the future. Any ONE brain training regiment only makes you better at the one thing being trained. But NEW EXPERIENCES in general, promise a varied and continual rewiring of the brain for a fluid and ever-changing development of intelligence. In other words, if you stay in your comfort zone, the comfort zone decays around you. In order to build intelligence or even to keep what you have, you need to be building new rooms, outside your comfort zone. If you consume a new media source in the morning, experiment with a new route to work, eat a new food for lunch, talk to a new person, or…try a NEW puzzle, you’re forcing your brain to rewire itself to be able to deal with these new experiences—you’re growing new neurons and forcing your old ones to scramble to create new connections.

Here’s what that means for your brain-training regimen: doing a puzzle is little more than busywork; it’s the act of figuring out how to do it that makes you smarter. Sit down and read the directions. If you understand them immediately and know how you should go about solving a puzzle, put it down and look for something else…something new. It’s not just use it or lose it. It’s use it in a novel way or lose it. Try it. Your brain will thank you for it.

Garth Sundem works at the intersection of math, science, and humor with a growing list of bestselling books including the recently released Brain Candy: Science, Puzzles, Paradoxes, Logic and Illogic to Nourish Your Neurons, which he packed with tasty tidbits of fun, new experiences in hopes of making readers just a little bit smarter without boring them

into stupidity. He is a frequent on-screen contributor to The Science Channel and has written for magazines including Wired, Seed, Sand Esquire. You can visit him online or follow his Twitter feed.

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development.

Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

]]>

Scientists are becoming more interested in trying to pinpoint precisely what’s going on inside our brains while we’re engaged in creative thinking. Which brain chemicals play a role? Which areas of the brain are firing? Is the magic of creativity linked to one specific brain structure? The answers are not entirely clear. But thanks to brain scan technology, some interesting discoveries are emerging. ScriptPhD.com was founded and focused on the creative applications of science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising, fields traditionally defined by “right brain” propensity. It stands to reason, then, that we would be fascinated by the very technology and science that as attempting to deduce and quantify what, exactly, makes for creativity. To help us in this endeavor, we are pleased to welcome computer scientist and writer Ravi Singh’s guest post to ScriptPhD.com. For his complete article, please click “continue reading.”

Before you can measure something, you must be able to clearly define what it is. It’s not easy to find consensus among scientists on the definition of creativity. But then, it’s not easy to find consensus among artists, either, about what’s creative and what’s not. Psychologists have traditionally defined creativity as “the ability to combine novelty and usefulness in a particular social context.” But newer models argue that these type of definitions, which rely on extremely-subjective criteria like ‘novelty’ and ‘usefulness,’ are too vague. John Kounios, a psychologist at Drexel University who studies the neural basis of insight, defines creativity as “the ability to restructure one’s understanding of a situation in a non-obvious way.” His research shows that creativity is not a singular concept. Rather, it’s a collection of different processes that emerge from different areas of the brain.

In attempting to measure creativity, scientists have had a tendency to correlate creativity with intelligence—or at least link creativity to intelligence—probably because we believe that we have a handle on intelligence. We believe can measure it with some degree of accuracy and reliability. But not creativity. No consensus measure for creativity exists. Creativity is too complex to be measured through tidy, discrete questions. There is no standardized test. There is yet to be a meaningful “Creativity Quotient.” In fact, creativity defies standardization. In the creative realm, one could argue, there’s no place for “standards.” After all, doesn’t the very notion of standardization contradict what creativity is all about?

To test creativity, researchers have historically attempted to test divergent thinking, an assessment construct originally developed in the 1950s by psychologist J. P. Guilford, who believed that standardized IQ tests favored convergent thinkers (who stay focused on solving a core problem), rather than divergent thinkers (who go ‘off on tangents’). Guilford believed that scores on IQ tests should not be taken as a unidimensional measure of intelligence. He observed that creative people often score lower on standard IQ tests because their approach to solving the problems generates a larger number of possible solutions, some of which are thoroughly original. The test’s designers would have never thought of those possibilities. Testing divergent thinking, he believed, allowed for greater appreciation of the diversity of human thinking and abilities. A test of divergent thinking might ask the subject to come up with new and useful functions for a familiar object, such as a brick or a pencil. Or the subject might be asked to draw the taste of chocolate. You can see how it would be very difficult, if not impossible to standardize a “correct” answer.

Eastern traditions have their own ideas about creativity and where it comes from. In Japan, where students and factory workers are stereotyped as being too methodical, researchers are studying schoolchildren for a possible correlation between playfulness and creativity. Nath philosopher Mahendranath wrote that man’s “memory became buried under the artificial superstructure of civilization and its artificial concepts,” his way of saying that that too much convergent thinking can inhibit creativity. Sanskrit authors described the spontaneous and divergent mental experience of sahaja meditation, where new insights occur after allowing the mind to rest and return to the natural, unconditioned state. But while modern scientific research on meditation is good at measuring physiological and behavioral changes, the “creative” part is much more elusive.

Some western scientists suggest that creativity is mostly ascribed to neurochemistry. High intelligence and skill proficiency have traditionally been associated with fast, efficient firing of neurons. But the research of Dr. Rex Jung, a research professor in the department of neurosurgery at the University of New Mexico, shows that this is not necessarily true. In researching the neurology of the creative process, Jung has found that subjects who tested high in “creativity” had thinner white matter and connecting axons in their brains, which has the effect of slowing nerve traffic. Jung believes that this slowdown in the left frontal cortex, a brain region where emotion and cognition are integrated, may allow us to be more creative, and to connect disparate ideas in novel ways. Jung has found that when it comes to intellectual pursuits, the brain is “an efficient superhighway” that gets you from Point A to Point B quickly. But creativity follows a slower, more meandering path that has lots of little detours, side roads and rabbit trails. Sometimes, it is along those rabbit trails that our most revolutionary ideas emerge.

You just have to be willing to venture off the main highway.

We’ve all had aha! moments—those sudden bursts of insight that solve a vexing problem, solder an important connection, or reinterpret a situation. We know what it is, but often, we’d be hard-pressed to explain where it came from or how it originated. Dr. Kounios, along with Northwestern University psychologist Mark Beeman, has extensively studied the the “Aha! moment.” They presented study participants with simple word puzzles that could be solved either through a quick, methodical analysis or an instant creative insight. Participants are given three words then are asked to come up with one word that could be combined with each of these three to form a familiar term; for example: crab, pine and sauce. (Answer: “apple.”) Or eye, gown and basket. (Answer: ball)

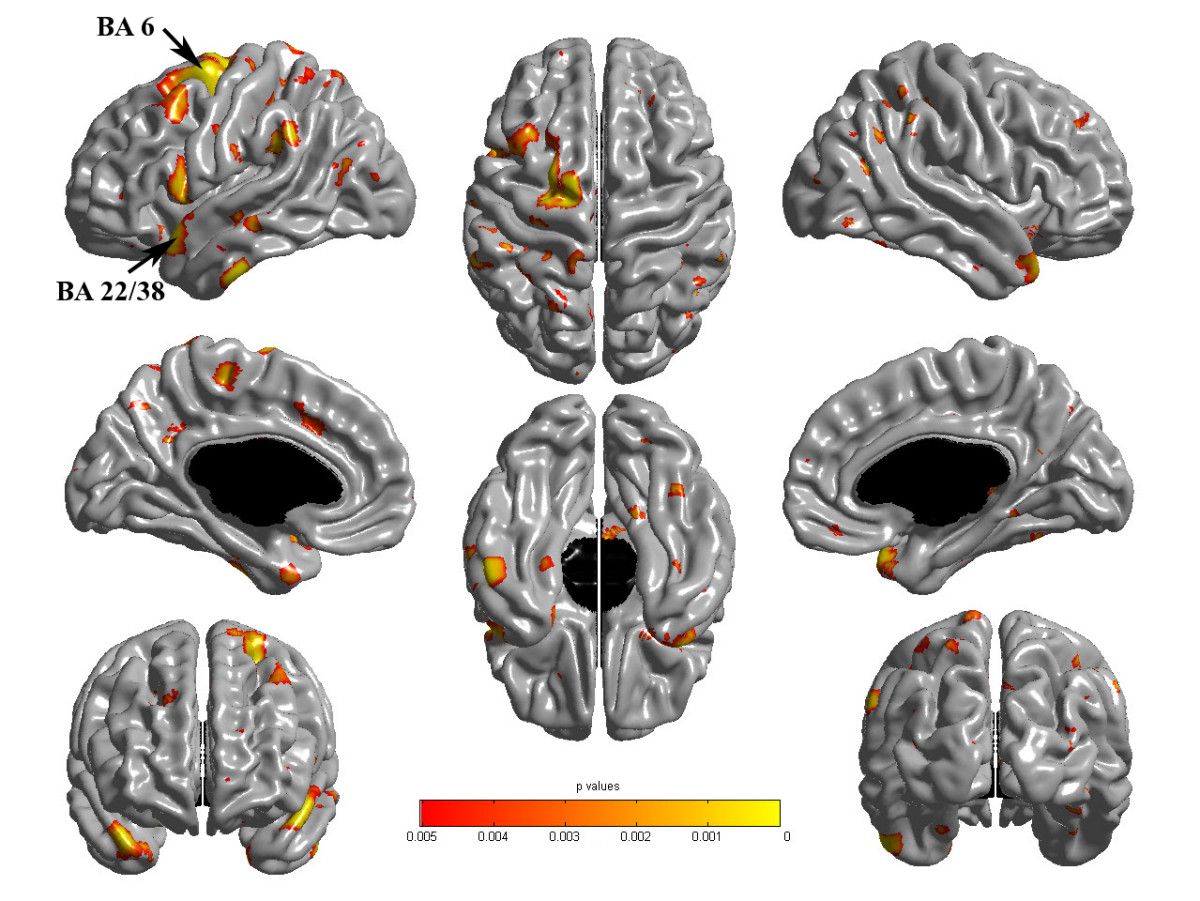

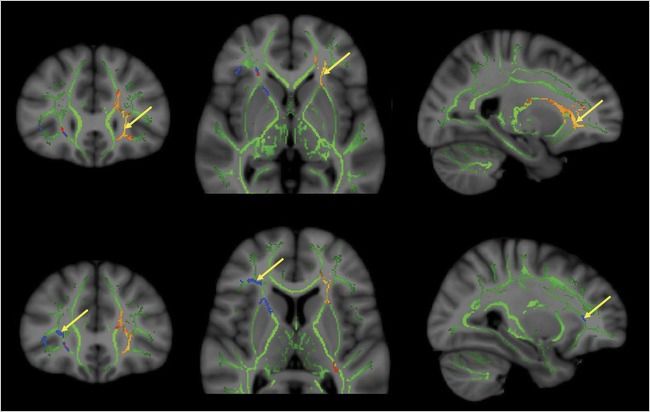

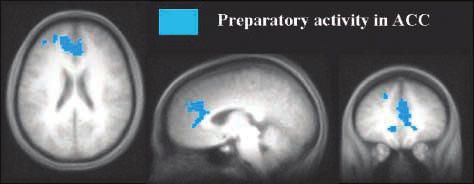

About half the participants arrived at solutions by methodically thinking through possibilities; for the other half, the answer popped into their minds suddenly. During the “Aha! moment,” neuroimaging showed a burst of high-frequency activity in the participants’ right temporal lobe, regardless of whether the answer popped into the subjects’ minds instantly or they solved the problem methodically. But there was a big difference in how each group mentally prepared for the test question. The methodical problem solvers prepared by paying close attention to the screen before the words appeared—their visual cortices were on high alert. By contrast, those who received a sudden Aha! flash of creative insight prepared by automatically shutting down activity in the visual cortex for an instant—the neurological equivalent of closing their eyes to block out distractions so that they could concentrate better. These creative thinkers, Kounios said, were “cutting out other sensory input and boosting the signal-to-noise ratio” to enable themselves retrieve the answer from the subconscious.

Creativity, in the end, is about letting the mind roam freely, giving it permission to ignore conventional solutions and explore uncharted waters. Accomplishing that requires an ability, and willingness, to inhibit habitual responses, take risks. Dr. Kenneth M. Heilman, a neurologist at the University of Florida believes that this capacity to let go may involve a dampening of norepinephrine, a neurotransmitter that triggers the fight-or-flight alarm. Since norepinephrine also plays a role in long-term memory retrieval, its reduction during creative thought may help the brain temporarily suppress what it already knows, which paves the way for new ideas and discovering novel connections. This neurochemical mechanism may explain why creative ideas and Aha! moments often occur when we are at our most peaceful, for example, relaxing or meditating.

The creative mind, by definition, is always open to new possibilities, and often fashions new ideas from seemingly irrelevant information. Psychologists at the University of Toronto and Harvard University believe they have discovered a biological basis for this behavior. They found that the brains of creative people may be more receptive to incoming stimuli from the environment that the brains of others would shut out through the the process of “latent inhibition,” our unconscious capacity to ignore stimuli that experience tells us are irrelevant to our needs. In other words, creative people are more likely to have low levels of latent inhibition. The average person becomes aware of such stimuli, classifies it and forgets about it. But the creative person maintains connections to that extra data that’s constantly streaming in from the environment and uses it.

Sometimes, just one tiny stand of information is all it takes to trigger a life-changing “Aha!” moment.

Ravi Singh is a California-based IT professional with a Masters in Computer Science (MCS) from the University of Illinois. He works on corporate information systems and is pursuing a career in writing.

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development.

Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

]]>

Dr. Mark Changizi, a cognitive science researcher, and professor at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, is one of the most exciting rising stars of science writing and the neurobiology of popular culture phenomena. His latest book, The Vision Revolution, expounds on the evolution and nuances of the human eye—a meticulously designed, highly precise technological marvel that allows us to have superhuman powers. You heard me right; superhuman! X-ray vision, color telepathy, spirit reading, and even seeing into the future. Dr. Changizi spoke about these ideas, and how they might be applied to everything from sports stars with great hand-eye coordination to modern reading and typeface design with us in ScriptPhD.com’s inaugural audio podcast. He also provides an exclusive teaser for his next book with a guest post on the surprising mindset that makes for creative people. Read Dr. Changizi’s guest post and listen to the podcast under the “continue reading” cut.

You are an idea-monger. Science, art, technology—it doesn’t matter which. What matters is that you’re all about the idea. You live for it. You’re the one who wakes your spouse at 3am to describe your new inspiration. You’re the person who suddenly veers the car to the shoulder to scribble some thoughts on the back of an unpaid parking ticket. You’re the one who, during your wedding speech, interrupts yourself to say, “Hey, I just thought of something neat.” You’re not merely interested in science, art or technology, you want to be part of the story of these broad communities. You don’t just want to read the book, you want to be in the book—not for the sake of celebrity, but for the sake of getting your idea out there. You enjoy these creative disciplines in the way pigs enjoy mud: so up close and personal that you are dripping with it, having become part of the mud itself.

Enthusiasm for ideas is what makes an idea-monger, but enthusiasm is not enough for success. What is the secret behind people who are proficient idea-mongers? What is behind the people who have a knack for putting forward ideas that become part of the story of science, art and technology? Here’s the answer many will give: genius. There are a select few who are born with a gift for generating brilliant ideas beyond the ken of the rest of us. The idea-monger might well check to see that he or she has the “genius” gene, and if not, set off to go monger something else.

Luckily, there’s more to having a successful creative life than hoping for the right DNA. In fact, DNA has nothing to do with it. “Genius” is a fiction. It is a throw-back to antiquity, where scientists of the day had the bad habit of “explaining” some phenomenon by labeling it as having some special essence. The idea of “the genius” is imbued with a special, almost magical quality. Great ideas just pop into the heads of geniuses in sudden eureka moments; geniuses make leaps that are unfathomable to us, and sometimes even to them; geniuses are qualitatively different; geniuses are special. While most people labeled as a genius are probably somewhat smart, most smart people don’t get labeled as geniuses.

I believe that it is because there are no geniuses, not, at least, in the qualitatively-special sense. Instead, what makes some people better at idea-mongering is their style, their philosophy, their manner of hunting ideas. Whereas good hunters of big game are simply called good hunters, good hunters of big ideas are called geniuses, but they only deserve the moniker “good idea-hunter.” If genius is not a prerequisite for good idea-hunting, then perhaps we can take courses in idea-hunting. And there would appear to be lots of skilled idea-hunters from whom we may learn.

There are, however, fewer skilled idea-hunters than there might at first seem. One must distinguish between the successful hunter, and the proficient hunter – between the one-time fisherman who accidentally bags a 200 lb fish, and the experienced fisherman who regularly comes home with a big one (even if not 200 lbs). Communities can be creative even when no individual member is a skilled idea-hunter. This is because communities are dynamic evolving environments, and with enough individuals, there will always be people who do generate fantastically successful ideas. There will always be successful idea-hunters within creative communities, even if these individuals are not skilled idea-hunters, i.e., even if they are unlikely to ever achieve the same caliber of idea again. One wants to learn to fish from the fisherman who repeatedly comes home with a big one; these multiple successful hunts are evidence that the fisherman is a skilled fish-hunter, not just a lucky tourist with a record catch.

And what is the key behind proficient idea-hunters? In a word: aloofness. Being aloof—from people, from money, from tools, and from oneself—endows one’s brain with amplified creativity. Being aloof turns an obsessive, conservative, social, scheming status-seeking brain into a bubbly, dynamic brain that resembles in many respects a creative community of individuals. Being a successful idea-hunter requires understanding the field (whether science, art or technology), but acquiring the skill of idea-hunting itself requires taking active measures to “break out” from the ape brains evolution gave us, by being aloof.

I’ll have more to say about this concept over the next year, as I have begun writing my fourth book, tentatively titled Aloof: How Not Giving a Damn Maximizes Your Creativity. (See here and here for other pieces of mine on this general topic.) In the meantime, given the wealth of creative ScriptPhD.com readers and contributors, I would be grateful for your ideas in the comment section about what makes a skilled idea-hunter. If a student asked you how to be creative, how would you respond?

Mark Changizi is an Assistant Professor of Cognitive Science at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in New York and the author of The Vision Revolution and The Brain From 25,000 Feet. More of Dr. Changizi’s writing can be found on his blog, Facebook Fan Page, and Twitter.

ScriptPhD.com was privileged to sit down with Dr. Changizi for a half-hour interview about the concepts behind his current book, The Vision Revolution, out in paperback June 10, the magic that is human ocular perception, and their applications in our modern world. Listen to the podcast below:

~*ScriptPhD*~

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology

in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development.

Follow us on Twitter and our Facebook fan page. Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

]]>

The Human Spark is a new three-part documentary special on PBS in which Alan Alda soldiers after the genetic and cognitive elements that make him smarter than your average chimpanzee. In the first episode, he travels to numerous archaeological sites and many of the world’s finest research centers to look at how humans diverged from neanderthals and why we’re the ones writing the history books. Episode two tracks a series of experiments on chimpanzees and human children to illustrate the psychological differences. The final installment shows off some of the latest brain imaging studies and and linguistics research to postulate a theory on the nature of the ‘human spark’. With an interesting scientific premise as a basis, a hot field in which a lot of exciting, new information has been discovered within the last decade, and financial sponsorship by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, one of the most generous and prestigious in all of science, this should have been a knockout for PBS. Sadly, the finished product is merely another example of a strong concept with poor execution, punctuated by bloopers that the documentary’s creators were too pressed for content to take out.

REVIEW: The Human Spark (PBS)

ScriptPhD.com Grade: D

The Human Spark‘s one saving grace is that the first episode is filmed primarily inside the lab, showed the scientists working on fossils, and actually spotlighted some of the technology and methodologies that are making the current discoveries possible. Learning about how scientists date teeth was a pleasure compared with the rest of the program. Alda’s awkwardness as host is at times endearing but too often tedious. His voice-over work is fantastic, but when it comes to live action this scripted special feels a little too real. When the grad students sit down for lunch at the archeological site, Alan finally gets to vent what’s been on his mind since M.A.S.H. wrapped:

“Here’s what I don’t get. The people who moved out of Africa, and who we came to call the Neanderthals, who got here, and didn’t change much from the time they got here until the time they died out, although that was a long period of time, they survived but they didn’t change. They—they’re—their—they came from the same people we came from, and some- and then at some point we started changing. We started being able to change. And then we came up here. These two groups meet. Why did—having come from the same background—why were we able to change and they weren’t?”

On the plus side, after he got done asking this question, the filmmakers only had 50 more minutes of that hour left to fill. And you know they had smart scientists on the show, because one actually provided a cogent answer. Here’s what really kills the premise with this program—PBS did a lousy job editing because they had nothing better to show us. That’s the only justification for content like this. Alan was sent to six different countries to visit archaeological sites that all look the same anyway, so it’s hard to believe they couldn’t afford to do another take on that burning question of his. And as for the visuals, this filmmaker was thoroughly offended (more on this in a minute). The entirety of the show, experts throw huge abstract numbers at the audience: this skull is fifty thousand years old; this bead is over a hundred twenty thousand years old; here’s an imitation sea-shell from two hundred thousand years ago. It’s easier to read them here on the page, but that’s my point. Would it have killed them to put a lousy timeline up on the screen for 10 seconds? The only visual they could afford was a pirated Google Earth frame to show us where the neanderthals camped out. They had imitation sea-shells at that campfire. We just don’t know when.

In case you risk watching this travesty and twenty minutes in you choke on your own boredom, let ScriptPhD.com fill you in on what you missed during the last half hour: Alda shoots primitive projectile weapons at a plastic reindeer. (Yes, PBS members, your money is being well-spent!) The production crew craft an authentic stone-age spear, but instead of throwing it like our humanoid ancestors, Alda’s cheating with a fancy spear-thrower. And he still can’t hit a stationary Christmas decoration! After ten minutes of hopeful attempts ending in bitter disappointment comes the best part: he purportedly hits the thing, but we miss it because the camera’s zoomed in on his face, then it pans over to where someone obviously stuck a spear into the deer’s behind. With effects like that, who needs James Cameron?

Episode Two is an examination of what separates us from chimpanzees, our closest genetic relative. The second installment demonstrates even more clearly that poor presentation can be the death of good content. We’re greeted in this episode by Alda sitting between a chimp and a human child. As he clumsily reads the opening statement from the teleprompter, the kid jumps in with an answer to one of the rhetorical questions, but Alan just talks over him. No one thought that was worth a second take, but this time I think I know why. Across the table from that outspoken little boy was a menacing ball of barely-contained bloodlust. Apart from some developmental psychology, you will learn one important thing from this episode: chimpanzees hate Alan Alda. I’m talking about Hondo, The Human Spark’s sympathetic antagonist. Hondo is a male chimpanzee with an unfortunate childhood that would make Jane Goodall cry: stripped from his family at a young age, denied the furry harem that was his genetic birthright. Day after day, he endures the seemingly trivial experiments of his human captors, given a 50% chance at extracting a measly grape for his efforts. The biologist who describes his characteristics may or may not have finished puberty, his voice cracking with glee as he and Alda share some ground-breaking connection between monkey and car salesman. Does it surprise any of us 99 percenters that Hondo risks it all for one noble shot at wiping that disoriented grin off the aging star’s face? As our host and his eager partner-in-science engage in yet another conversation that didn’t need to be televised for a viewing public, I found myself rooting for Hondo as he hurls himself against the protective glass, proving that even though he can’t best a three year old at logic puzzles, this chimp knows a thing or two about the human spark.

And who can blame Hondo’s aggression, with a format born of the logic that to educate does not mean to entertain. “You’re getting it all wrong!” his expression screams as he fails another test to determine whether he can understand the concept of weight, and throws himself in frustration at the bars between him and his inquisitors. In all seriousness, the presentation does a huge disservice to the undeniable brilliance of the researchers introduced during this segment, particularly since PBS’s mantra is to educate through entertainment. These scientists are people who’ve devoted their entire professional lives to studying what it means to be human, people who conduct seemingly cutting-edge research, yet the program feels like a perfunctory grade-school field trip. How is it even possible to capture monkeys on camera for any extended period of time without it being entertaining? Episode 2 is a point-counterpoint competition between children and chimpanzees that showcases the somewhat mundane scientific method (performing test after test to discover the key differences in psychology). Although these tests illustrate the evidence, the conclusions drawn from them are much more exciting than the process.

The research hints at powerful revelations: the way human children are programmed to teach and learn may give us an evolutionary leg up. But even here, one is left with a lingering doubt: what if the human subjects are more teachable because they’re all children? The Human Spark would have us believe that the kid wins out because the adult chimpanzee would rather pursue the grape with his own strategy, ignoring the researcher’s demonstration. But don’t we afford the human adult the same courtesy, to ignore all rational advice and pleading, just go out and buy the boat, marry the fifth wife? My decidedly human confidence is not bolstered when, after being shown a box with both sliding and pull-out doors to reach the same grape, Alan can’t figure out how to get the darn thing open, either.

Shocking as it might be to believe, the final round of this documentary is the most exasperating. For one thing, it’s the most self-indulgent. As the camera rolls, Alda volunteers himself to the latest and greatest in brain imaging techniques, and some nervous tech compliments him on how bereft of open space his skull cavity remains. After some painful filler including re-used footage from the previous two episodes, we get to watch as different spots on his brain light up in correspondence with different actions. To reiterate, interesting conclusions masked by poor presentation. Nothing envelops an evening with a drowsy warmth like linguistics. At one point, it seems we are to believe that grammar is the root of the human spark. In as much time as it takes to start denying that to yourself, we’ve moved on to religion, coupled with a cheesy montage of people presumably…being religious. And then, like that poor chimpanzee on a crash course for Alda’s head, a relatively startling and profound conclusion: mankind’s ability to think and strategize about the future sets him apart, and one of these brains can (almost) prove it.

Film is a visual medium. Hearing scientists explain their research is one thing, but forcing us to watch them do it rather than illustrating the concepts is uncreative and lazy. Brilliant as they are, rarely would one of them dare to send an unedited, offhand remark out to their colleagues for peer-review, so why is this acceptable for public consumption? It’s just bad television. So is the lack of adequate visuals that even daytime cable programming can muster and the poor editing that accompanied this performance. Some of the backgrounds looked like they were slapped together from iMovie, which is a fine rudimentary program when you’re putting together your baby’s first steps to show grandma. Finally, economy. If running a dramatic series for twelve episodes throughout the season, maybe you might show some flashbacks during the finale to remind viewers of key plot points. But a three-part science special doesn’t need to be recycling footage from the first two to fill its third episode. There were about forty minutes of good material that were made to last three hours. Leaving in bad takes and long-winded responses to fill that time is an insult to the PBS audience’s attention span. Programs like this make up the nerdy half of the void that inspires blogs like this one. On the other side, you’ve got entertainers making a mockery of the realities of science, and before you lie the fruits of educators using a bludgeon where a crime-scene investigation would have done nicely.

Trailer:

The Human Spark premieres January 6, 13, and 20, 2010 at 8pm on PBS (check local listings).

Stephen Compson studied English and Physics at Pomona College. He writes fiction and screenplays and is currently working toward a Master of Fine Arts at UCLA’s School of Theater, Film & Television.

~*Stephen Compson*~

***********************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and pop culture. Follow us on Twitter and our Facebook fan page. Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.