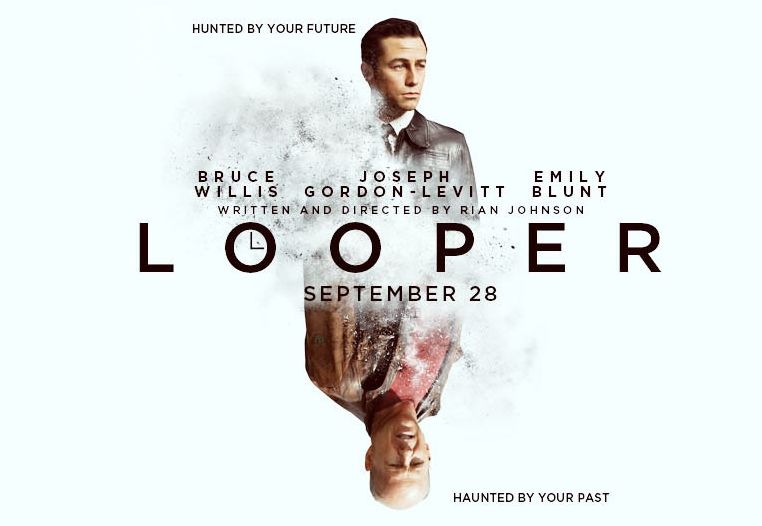

In the year 2042, time travel has not yet been invented. But by the year 2072, that is no longer the case. Nevertheless, it is outlawed, inaccessible to all but the most powerful and violent gangs in an economically repressed dystopia. Due to scientific advances of that era, it is impossible to dispose of a body without a trace, so the criminal gangs use the time travel to execute their “trash,” sending the bodies back in time to be executed by hit men called Loopers. The body vanishes from the future, but never existed in the present. Unless something goes terribly awry. Such is the setup of Rian Johnson’s bleak, brilliant sci-fi film Looper, a shrewd commentary on how we use technology, the value of a human life and whether a destiny can be changed. It is easily the best sci-fi film since 2010’s Inception, and surely one of the best of this year in any genre. Full ScriptPhD review, below.

Joe (Joseph Gordon-Levitt) is a Looper, a very desirable and profitable position in a time over-run with vagrant raids, poverty, hopelessness and violence. The job has a 30-year finite time span, at which time the Looper is sent back into time to be exterminated, and a younger, genetically identical version of him starts job all over again. This is called “closing the loop.” The consequences, shown early in the film, of not closing the loop are dire, both for the younger Looper and his older counter-part. But Joe, an emotionally detached junkie, treats his executions with a regimented ennui. Until one day, when a loop fails to show up at the expected hour. In a split second, Joe recognizes the man as the older version of himself (Bruce Willis), and the brief hesitation allows Old Joe to escape, unleashing the fury of the warlords on both of them across the boundaries of time.

The future painted by Johnson is noir-lugubrious but stops short of the over-the-top post-apocalyptic dreariness of Blade Runner or Children of Men. Instead, the issues of social equality, money and humanity that we struggle with today are exaggerated under the umbrella of traditional sci-fi existentialism. The Looper future is also one filled with abject unfairness. Hungry vagrants that steal food out of desperation are shot immediately by armed citizens. A mobster (Jeff Daniels) sent from the future to run the loopers quenches his boredom by running the city with tyranny, leaving the dirty work of closing loops to violent thugs. Worst of

all is the news from the future of the appearance of a tyrannical warlord named The Rainmaker, who is closing all the loops one by one.

At first, the relationship between Young Joe and Old Joe is antagonistic. All Old Joe wants to do is survive and warn his younger counterpart not to repeat the mistakes he made, especially trying to avoid the death of his wife. All Young Joe wants to do is close his loop, collect the money and make right with the mob. But they grow to grudgingly protect one another amidst a greater goal—finding and eliminating the younger version of The Rainmaker in the present. A series of mysterious maps and codes lead Young Joe to a farmhouse where a young woman, Sarah (Emily Blunt), and her son Cid (Pierce Ganon) are hiding out. As it dawns on Young Joe that Cid is the Young Rainmaker, he wrestles with whether a deleterious future can truly be avoided either for himself or Cid, all while chasing Old Joe and being chased himself.

From the sci-fi element, Looper craftily wedges evolution of technology in a future world not so unlike our own. There is time travel, a quirky genetic mutation that affects 10% of the population (they can levitate quarters!) and expected audiovisual upgrades to touch-screen technology. But there are also familiar elements—books, records, refrigerators and even cars—that make these developments feel natural and real. Even time travel is treated not as an exotic luxury but a quotidian burden. The one and only scene of time travel in the film shows a rather simple metal tube that transports people to a time point in an empty field.

Whether time travel is actually possible in reality is a point of continuing contention with physicists. First referenced in H.G. Wells’s The Time Machine, time travel has been a steady staple of the sci-fi canon, but it wasn’t until Albert Einstein unraveled the four dimensions of space with his Theory of Relativity in 1915 that the notion seemed tenable. And of course, in theory, time travel is a very real occurrence, since we know that time passes more slowly the closer you approach the speed of light. Physicists such as Stephen Hawking have grappled with other time-space phenomena such as wormholes and quantum theory that might facilitate time jumping. Most scientists, however, are unified in their belief that if a time machine were ever built, it would be used exclusively for going forward in time, and not backwards, for many of the same quandaries proposed in Looper, particularly whether you can change the course of events that are destined to happen in the future.

But Looper doesn’t contend with any of that. It just assumes physicists have solved these hurdles and focuses on a smart, intricate, well-written story. It’s a film that treats its audience with respect, asking for patience in the more complicated plot points, and rewarding it with a satisfying, shocking crescendo worthy of its metaphysical journey. Indeed, Looper might be the first film of the 21st Century to provide a truly real purview into the ethical quandaries, and frightening realities, that time travel might present to us should it ever come to pass.

Preview trailer here:

Looper goes into release nationwide on September 28, 2012.

~*ScriptPhD*~

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development.

Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

]]>

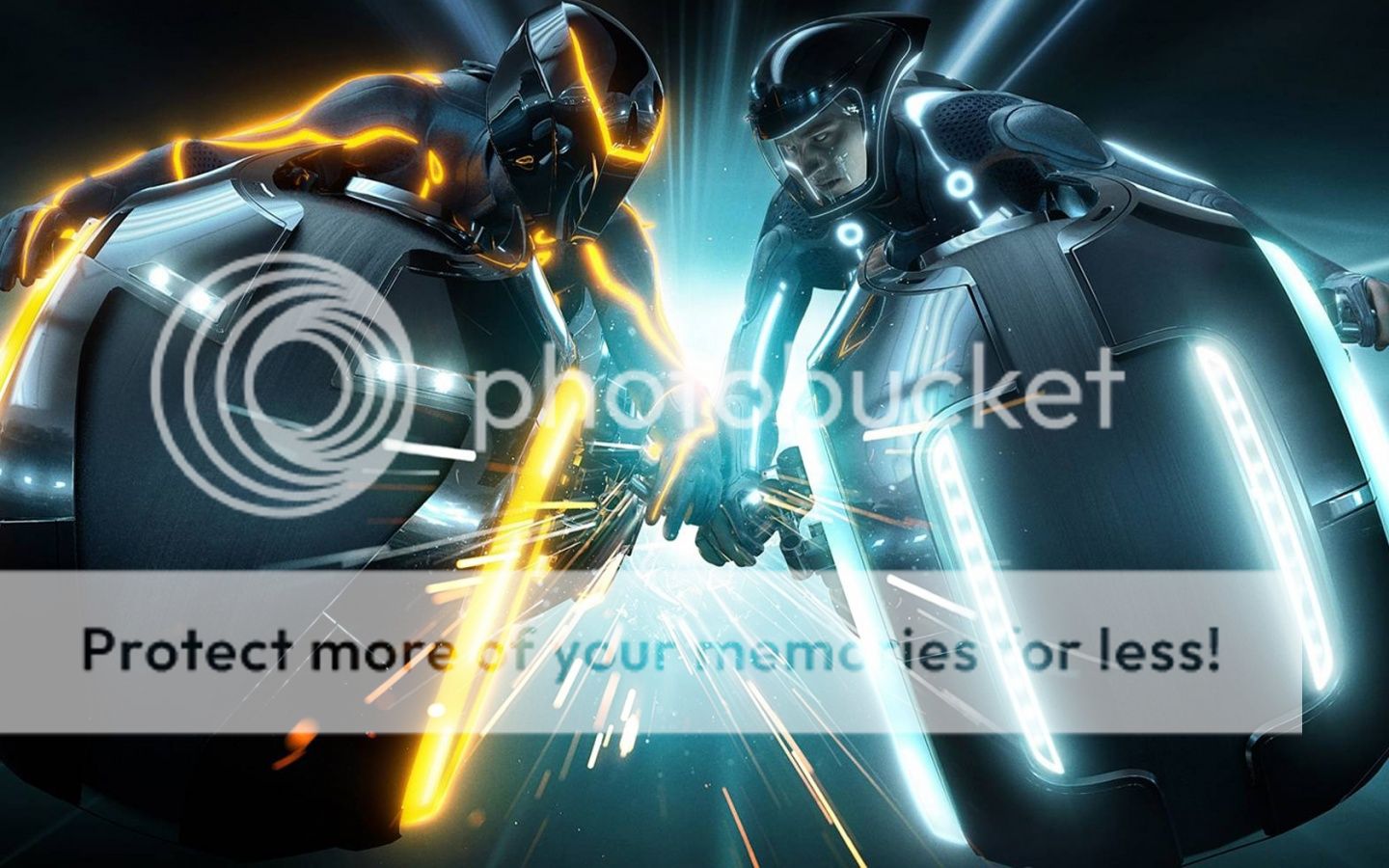

It has been 28 years since the release of the enormously groundbreaking science-fiction adventure Tron, the story of Kevin Flynn, a video game programmer that gets sucked into the virtual grid of the very game he created. As Flynn’s son, now cyber-reunited with his father, points out, decades of technology have bestowed us with cell phones, wi-fi, the internet, and even virtual dating. But one immutable fact stands the test of time—great sci-fi is great sci-fi. Without upstaging the original, TRON: Legacy manages a sleek, stylish, clever sequel utterly germane to the times we live in. ScriptPhD.com got treated to a preview screening in Hollywood this week. Our full review under the “continue reading” cut.

REVIEW: TRON: Legacy

ScriptPhD Grade: B+

TRON: Legacy briskly picks up right where Tron left off. Cleverly superimposed “flashback” scenes (and a very digitally altered Jeff Bridges) are provided for the benefit of fans who missed the original. Genius video game programmer Kevin Flynn (Bridges) has found a way to transport himself into the virtual grid of his game—a place where minutes are hours of time on Earth. He tells his son that he’s discovered a miracle, and promises to show him the Tron world, only to forever disappear. Flash forward to a 27-year-old Sam Flynn (Garrett Hedlund): reckless, bored, apathetic, but a regular chip off the old techie block, a geeky rebel without a cause. Encom, the developer of Tron, has now become a software hegemony—Atari meets Apple—and has strayed far from Kevin’s principle of freeware open to all. After sabotaging the company’s grand operating software launch, Sam is visited by his father’s partner Alan Bradley (Bruce Boxleitner), who has never given up on Kevin. Alan tells Sam that he’s received a mysterious page from Kevin, and begs him to go to the old arcade that he frequented as a kid. There, Sam discovers his dad’s secret underground office and the portal that transports him to the digital grid of Tron.

The world that Sam finally visits is far from the utopia his father envisioned. He is first grouped with other with other deficient “programs” for inspection, outfitted with a sleek gamer outfit and disc (half memory-storage device, half weapon), and thrust into a world of brutal gladiator games where the only goal is survival and the rules change with each treacherous level. No longer is this gaming world one of skill and possibility. It is dangerous, seedy, and lachrymose, as evidenced by the monochromatic whites, greys, and blacks that are virtually the only colors displayed throughout the film. And Clu is no longer the brave warrior digital replica of his father; he is a brutal overlord who committed virtual genocide, hacked the program, and has ultimate plans to teleport to Earth to be with humans. Sam is rescued from the grid by Quorra (Olivia Wilde), an advanced, evolved program not initially designed to go off the grid. She is the “miracle” that Kevin lauded—an isometric being, an entirely new life form, and the last surviving one. When reunited with Sam, Kevin recounts getting “trapped” in the grid after a violent overthrow by Tron and Clu. In addition to executing a genocide against the isos (forever closing the portal to the outside world), they stole Kevin’s original disc for their nefarious purposes. With the help of Quorra and Sam, Kevin has only 8 hours to overthrow Clu’s digital army until the portal closes again… forever.

TRON: Legacy largely has the feel of a 2-hour interactive video game, aided both by the color-coded costumes and a catchy, techno-pop soundtrack by Daft Punk. It’s also a cheeky, subtle commentary on the idea of technological dominance over humans, often explored in science fiction. Is it so unlikely, NASA having just discovered a new non-carbon-based life form, that an evolutionary miracle like Quorra could happen? Could a wily programmer or physicist find himself ensnared in a digital grid? Highly unlikely in the short term, but with digital quantum teleportation on the horizon and China in quick pursuit of the physical variety, it’s not inconceivable in the future. Furthermore, thinking robots are no longer an aspiration, as the age of thinking, self-developing robots has arrived. Even the internet, on which one would argue we are wholly dependent today, has been shown by physicists to abide by the same laws of physics as an integrated circuit! “Our worlds are more interconnected than you think,” Kevin Flynn reminds his son. Quorra, adorably naïve and inexperienced, voraciously devours human literature and longs more than anything to see the sun shine. There is a delicate beauty to humanity that an orderly grid of 0’s and 1’s can ultimately never replicate. We should lift our eyes away from our smartphones, Wiis, iPads, and laptops to notice that every once in a while.

To be sure, TRON: Legacy is not reinventing sci-fi, tech-geek gizmo gadgetry, or a complicated storyline beyond “good guys defeat bad guys.” (Story development was not, in fact, a principal strength of the original Tron, which was considered a breakthrough in cinematic special effects.) Nevertheless, sci-fi fans, geeks and gamers will be able to feast on astounding visual mastery, life-size video games played out before your eyes, and science fiction/fantasy existentialism staple questions (who are we? what is humanity? what are the limits of technology and what we create?). Most importantly, it’s a relevant portal to our current age of digital enslavement, literally redefining modern life before our eyes. Above all else, TRON: Legacy is two hours of darned good entertainment.

View the trailer:

TRON: Legacy goes into wide release on December 17, 2010 in US theaters.

~*ScriptPhD*~

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development.

Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

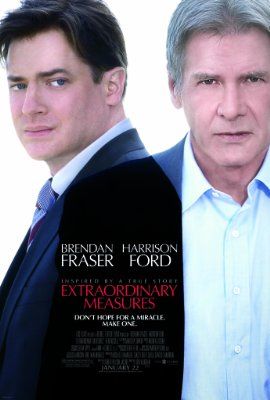

]]>A Father’s Love and a Scientist’s Dedication in a Race against Time

Imagine this scenario: you are a young married professional, a rising star in a well-respected pharmaceutical company. You have three children, two of which suffer from a rare, inherited genetic disease for which there is no cure. They will die in about a year or two. What do you do? Inspired by the book The Cure: How a Father Raised $100 Million – and Bucked the Medical Establishment – In a Quest to Save His Children by Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Geeta Anand, Extraordinary Measures is a drama about the real-life story of John Crowley (Brendan Fraser) and Dr. Robert Stonehill (Harrison Ford) as they work feverishly to find a cure for the disease afflicting Crowley’s children. The dramatic caveat is that said cure is based solely on a scientific theory. CBS Films’ motion picture debut touches on a myriad of salient modern-day issues, including personal morality, risk taking, scientific funding, pharmaceutical business practices, the dedication to science, professional relationships, and a man’s love for his family. For the full ScriptPhD.com review, please click “continue reading”.

REVIEW: Extraordinary Measures

ScriptPhD Grade: B+

Extraordinary Measures opens with an ambitious John Crowley (Brendan Fraser) rising up the corporate ladder in the global biopharmaceutical company Bristol-Myers Squibb. Despite two of his three children having a rare genetic disorder called Pompe Disease (pronounced Pom-pay). The family lives a relatively normal life, where birthday parties are celebrated and the children remain upbeat despite their condition. By day Mr. Crowley is a businessman, husband and father, by night he is lunging himself into the daunting world of reading scientific journals in the field of biochemistry, attempting to find and contact any scientist he feels may be on track to developing a cure for his two children. Throughout all of his heroic efforts, he is faithfully supported by his wife Aileen Crowley (Keri Russell).

During one Mr. Crowley’s many nights of pouring through scientific papers, he comes across the research of Robert Stonehill, MD, PhD. Dr. Stonehill is a role based on the real-life glycobiologist Dr. William Canfield. What is glycobiology and how does that involve Pompe disease? A glycobiologist is a scientist who studies sugars, and the enzymes which add sugar molecules to proteins. It is these enzymatic chemical modifications where Dr. Canfield is a leading expert and researcher. Pompe Disease is a rare (estimated at 1 in every 40,000 births), inherited and often fatal disorder that disables the heart and muscles (excellent overview). It is caused by mutations in a gene that makes an enzyme called alpha-glucosidase (GAA). Normally, the body uses GAA to break down glycogen, a stored form of sugar used for energy, in muscle cells. But in Pompe Disease, mutations in the GAA gene reduce or completely eliminate this essential enzyme. Excessive amounts of glycogen accumulate everywhere in the body, but the cells of the heart and skeletal muscles are the most seriously affected. Researchers have identified up to 70 different mutations in the GAA gene that cause the symptoms of Pompe disease, which can vary widely in terms of age of onset and severity. The severity of the disease and the age of onset are related to the degree of enzyme deficiency. If a person has only one mutated form of this gene and one normal copy, they are only a “carrier”—that is, they can pass it down to their children, but they themselves do not develop the disease. A person needs to have both copies of the mutated gene in order to have the disease. The Crowley children inherited the mutations for this disease from each parent.

The movie portrays Dr. Stonehill as a brilliant, albeit eccentric, scientist as dedicated to the pursuit of science as he is a cure, and Mr. Crowley as a devoted, loving father who will not quit in his search for a cure. Convinced Dr. Stonehill is on the right track to producing a therapy for Pompe disease, Mr. Crowley is able to meet Dr. Stonehill, currently working as a scientist at a university. Dr. Stonehill, while brilliant and confident in his scientific research and theories, admits that ultimately his work is only theoretical, and not yet empirically proven. Mr. Crowley asks Dr. Stonehill what would it take to get his research from the bench to the bedside of his children and others like them. In short, and bitterly reflective of modern pharmaceutical realities, Dr. Stonehill replies “money.” Dr. Stonehill informs Mr. Crowley that not all sound theories in science are funded, the competition for grant money is fierce. In addition, while Dr. Stonehill loves his research he is frustrated by the university owning the patent rights to his ideas. At this point, Mr. Crowley informs Dr. Stonehill there is a Pompe Disease Foundation which will fund his research. They agree to meet again later in time.

During this time, Mr. Crowley, who is still working for Bristol Myers Squibb, begins to realize his continued employment with the pharmaceutical behemoth might forever endanger finding a cure for his children. Concurrently, he and his wife struggle with the quandary of letting nature take its course versus the moral/ethical implications of trying to fix their children’s condition. Should Mr. Crowley quit his good-paying position, and leave to pursue a cure? Mr. Crowley and Dr. Stonehill decide to start a business together, seek out venture capitalists and ultimately receive the funds necessary to start a small biotechnology company. The issues (and there are many!) of starting and running a biotech company, something neither of them has ever done, are adroitly explored throughout the movie. When investors realize the company is burning through millions of dollars, they give Crowley and Stonehill an ultimatum: merge with someone who can make this drug or we are turning out the lights for good.

The company they form, Priozyme (the actual erstwhile Novazyme), is eventually bought by the fictitious pharma giant called Zymagen. In real life, Zymagen was actually the biotech company Genzyme. Zymagen already has three Pompe research teams, which Dr. Stonehill arrogantly believes this is because they don’t really know what they are doing. Dr. Stonehill is made the chief scientist for what is now Zymagen’s 4th Pompe research team. Mr. Crowley is made the Senior Vice President for the Pompe project, much to the dismay of Zymagen scientists, due to his lack of scientific training. Extraordinary Measures does a good job of portraying the acquisition as a clash between personalities (which is rampant in science) and the often-embraced adage in the scientific community that non-scientists cannot contribute to or advance scientific research to a measurable degree. In addition to Dr. Stonehill’s personality not being received well by Zymagen, Mr. Crowley has his own problems with their corporate leadership. At Zymagen each Pompe disease research team works on its own. The teams do not collaborate with each other at all, with no sharing of information. The corporate leadership believes this brings out the best; Mr. Crowley believes this significantly slows down scientific progress.

Ultimately, although Dr. Stonehill’s candidate enzyme is selected for clinical trials, a bevy of ethical concerns and scientific roadblocks stand in the way of getting the discovery past the laboratory and on the way to FDA approval. Mr. Crowley, who selflessly gave up virtually everything towards the discovery of a Pompe cure, must make the ultimate sacrifice in order to ensure that it is able to help his children. Incidentally, on April 28, 2006 the Food and Drug Administration granted marketing approval for Myozyme® (alglucosidase alfa) in the U.S., indicated for use in patients with Pompe disease (GAA deficiency). While Extraordinary Measures doesn’t get into the gritty details of the true politics behind a lot of pharmaceutical company drug target choices, funding and scientific arm-wrestling, it does an excellent job of giving the lay public a general overview, which has been (with the exception of the brilliant The Constant Gardner) largely cinematically absent. For anyone curious about the drug discovery process, and the anguish both on the part of families and scientists desperately hoping for a cure, this movie is a must-see.

Brendan Fraser on playing the real John Crowley: click here.

Extraordinary Measures goes into wide release on January 22, 2009 in theatres nationwide

Trailer:

NeuroScribe obtained a BS in Biology, and a PhD in Cell Biology with a strong emphasis in Neuroscience. When he’s not busy freelancing for ScriptPhD.com he is out in the field perfecting his photography, reading science policy, and throwing some Frisbee.

~*NeuroScribe*~

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development.

Follow us on Twitter and our Facebook fan page. Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

]]>

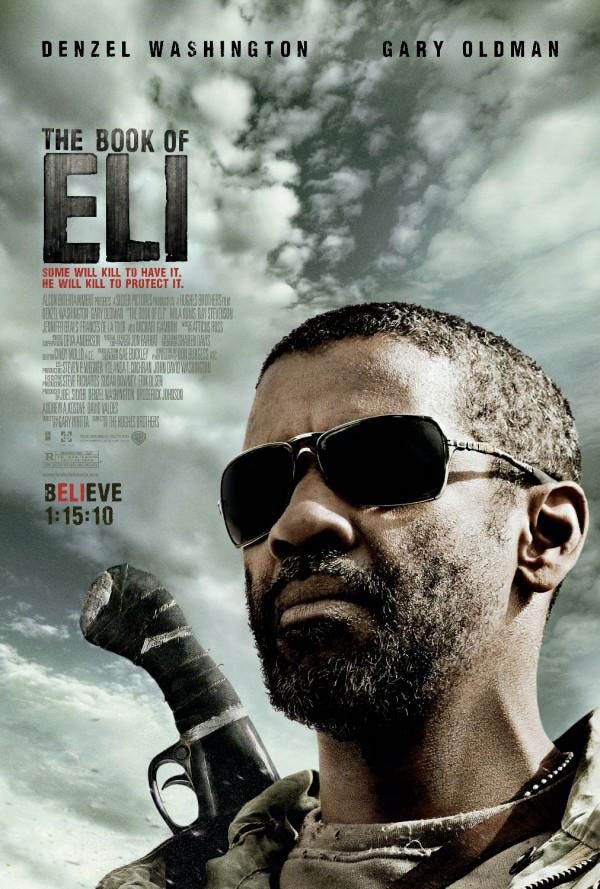

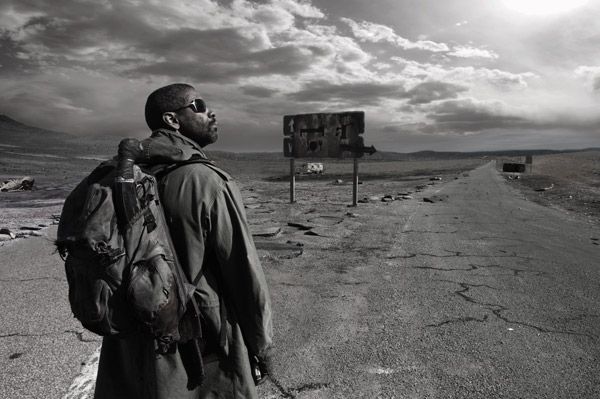

Picture this: a mysterious Man with No Name comes into a tiny desert town that’s dominated by a manipulative and powerful bossman. He has something the bossman wants and won’t give it up – and No Name is an almost supernaturally powerful fighter; you really don’t want to mess with him. Before the battle between Good and Evil is over, the Man with No Name has decimated the bossman’s thug-army and brought the evil leader low, the dusty little settlement is either burned to the ground or better off than before he arrived, and off he goes, continuing his mysterious journey – always in motion, never at peace. Except for a tie-‘em-up ending that’s tacked on to the back of The Book of Eli, that’s pretty much what you’ve got here: a post-apocalyptic tale of the mysterious hero vs. the bully prince, just like an old Sergio Leone/Clint Eastwood spaghetti western. Just replace Eastwood with Denzel Washington, replace the Old West with the near future after a global catastrophe, cast a painfully over-the-top Gary Oldman as the Bad Boss, give newcomer Mila Kunis the inevitable pretty girl/spunky sidekick role, and you’re golden. Or at least should have been. Unfortunately for the viewing audience, there’s more Sergio Leone than Cormac McCarthy in this ponderous and unconvincing post-apocalyptic allegory. For a full review, please click “continue reading”.

REVIEW: The Book of Eli

ScriptPhD.com Grade: C

If The Book of Eli had simply stuck with the aforementioned premise—an entertaining if derivative version of Mad Max Goes West—it might have worked just fine. Instead, the film is hobbled by implausibility in concept and execution, a thick coating of a strange and bitter religious message, and a slower-than-a-shamble pacing that relies heavily on squinty eyes, brows raised at sounds no one can hear, and lots and lots of walking. Slowly. In silhouette. Without sound.

On a purely technical level, The Book of Eli is rather beautiful in its bleakness. The production design is convincing (ultimately the most convincing thing about Eli’s incredibly drab afterworld) and the cinematography is oddly rich, despite being stuffed to the choke-point with vast cloudy panoramas just one notch away from the monochromatic. And the pure charisma of actors like Washington and Oldman can’t be denied, especially when they’re combined with clever near-cameos by the likes of Malcolm McDowell, Michael Gambon (Dumbledore does Tombstone? Really?) and a surprisingly convincing Tom Waits, who provides the most enjoyable two minutes of the entire movie. There are professionals at work here; they know what they’re doing and you can’t keep yourself from watching them, no matter what.

Still, underneath the almost balletic fight-scene choreography and Denzel’s thousand-yard stare, there’s a serious set of problems with The Book of Eli, beginning with the book itself. It’s giving away almost nothing at all to let you in the ‘secret’—that The Book in question is, indeed, The Book, the Good One, the King James Edition of the Holy Bible. The movie itself does everything but spray-paint the name of the book on the camera lens in the first twenty minutes, and confirms it with a round of somber-yet-still-embarrassing dialogue a few minutes later. It would be nice if there was a bit more mystery to it, but that’s not really the issue. The problem comes when we’re asked to believe that this is literally that only copy of the Bible to survive the holocaust; that all the others were destroyed in the disaster or by vengeful humans immediately

after they crawled out of their underground shelters.

What’s more, we’re expected to believe that even the idea of religion—the ancient meme of having a God or even Gods—has somehow been lost to the world in a few short years. Its best (or worst) illustration is embodied in one particularly embarrassing scene—one that evoked audible consensus groans from the crowd of critics at a recent screening—when Mila Kunis’ character tries to show her astonished mother the previously undreamt of, brand new idea of “saying grace” that Eli taught her the night before, implying that even the most basic notion of prayer seems to have been forgotten. Oldman’s bully-boy bossman has to tell her how to end this nameless ‘thing’ she’s learned from Eli. “Amen,” he grumbles. “The word you’re looking for is Amen.” As if even than fundamental idea, one absolutely essential and universal to virtually any society during its darkest times, has been burned out of the human mind.

Denzel Washington on the stunts in the making of The Book of Eli:

This isn’t just rickety world-building, done simply to prove a point or make a metaphor (though it’s that as well). This is also bad science, though in this case the science in question is anthropology rather than physics or biochemistry. Every society, at every level of development has its God or Gods; all of them have some sort of prayer or petitioning process, some means to communicate with their deities. To presuppose that Americans—or any human society, really—would lose the fundamental notion of God and Religion, and would do it in a single thirty-year span, is just too much to accept. It gives the movie an unrealistic and preachy quality that it never quite escapes.

It is this lack of anthropological gravitas that makes Eli’s post-apocalyptic world simply unbelievable. There is no color there, no music, no art, no education, and no love; sex itself is present only as prostitution or rape. Even simple hygiene and literacy have disappeared. There is still rubble blocking Main Street and the corpses of rusting cars still huddle at the curb—and this in the middle of the nameless town square thirty yeas after the Flash that ended it all. This isn’t a transplanted town of the Old West, despite the genre-specific similarities. This is civilization seen as an eternal refugee camp, filled with people who are more like Morlocks than humans, with all the filth and hopelessness that implies.

And then there’s the religious notion that empowers Eli’s quest—the idea that the Book, the book itself, not the messages it carries—has some magical, talismanic property. Without the presence, the magical power, of the King James Bible, the movie tells us, people have descended into post-literate barbarism; humans will begin to act human again only with the resurrection of the Bible itself, and even then, only if it’s returned to the ‘right’ hands; otherwise this magic book will become a weapon of mass destruction instead of salvation. The ideas that are memorialized in the Bible are barely acknowledged here, much less discussed, beyond the recitation of a few of its most painfully obvious verses and a misremembrance of the Golden Rule. But the book is of supreme importance, worth nearly endless bloodshed to move to its true destination, which is really nothing more than a return to the hands of a slightly less revolting but no less isolated elite.

What’s more, it’s worth noting that Denzel’s Eli is not, by any stretch, a Christian or a hero, not even one of those reluctant-hero types. He does not preach the Bible’s teachings—he can’t even bear to say the name of the book aloud until the last ten minutes of the movie, and you won’t hear the name of “Jesus” at all in Eli, not once. He does not behave like Jesus, either; quite the contrary, he ignores those in need when he encounters them on the road; he keeps even the very existence of the Word to himself, constantly denying he even has the book at all, and he evades or kills anyone who gets in his way as he continues his relentless vision quest. If there is an underlying message about religion in this film, the message is that religion is an amoral force, one that can be used for good or evil, without any intrinsic positive value at all. That, and the idea that humans, left to their own devices, are just No Damn Good; that given half a chance (and no magic Bibles to stop it), we will sink into grimy barbarism and self-destruction, up to and including cannibalism, in the space of a single generation.

Not exactly a message of hope.

The plot itself has some significant difficulties that really don’t matter in the long run, and the implicit geography of the post apocalyptic world is just plain wrong. Worst of all, the last fifteen minutes of the movie, in which the Book’s ultimate fate is revealed and all the twists begin to explode like land mines planted along the way, is almost laughably problematic. But there is a visual power in Eli, and throughout we are clearly in the hands of some very talented actors that can make us keep watching no matter what we might be thinking. Bottom line? You’ll get a better post-apocalyptic pop from The Road, Mad Max, A Canticle for Leibowitz, or even Fallout 3 than you’ll get from The Book of Eli.

The Book of Eli goes into wide release in theatres on January 15, 2010.

Trailer:

Brad Munson is a Los Angeles-based writer, editor, marketing coach, and advertising creative content developer. He is the author of The Mad Throne, Inside Men In Black II, and Rain. He is also the Editor-in-Chief of the fantasy, sci-fi, horror website All About The Rush.com.

~*Brad Munson*~

******************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development.

Follow us on Twitter and our Facebook fan page. Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

]]>

One of my favorite movies as a kid, and now, as a professional scientist, is Andromeda Strain. The heroes are mostly older, professorial types who work feverishly to understand an alien organism and save the planet. After being asked to review ReAction! Chemistry in the Movies for ScriptPhD.com, I was so curious to consume (with relish) the book’s guesswork about the chemistry found in Andromeda Strain. After returning to the beginning of the book and giving it a read, I was thrilled to find that ReAction! is a detailed, thoughtful exploration of the representation of chemistry in film. The book addresses, first and foremost, the fact that chemistry can play a lead role in film. The authors also discuss the dichotomy between the “dark” and “bright” sides of chemistry (and science) as illustrated by films in which chemistry or chemists play a central role. Also included are several playful explorations of the real science behind some famous examples of fictional chemistry in film. After the break is a full review of the book along with an in-depth interview with authors Mark Griep and Majorie Mikasen on the process of working together as chemist and artist, portrayal of chemists in film and how film can change public perception in science.

Often referred to as the “central science,” chemistry (and chemists) have a rich history of adapting to focus on the problems of their day. Therefore, chemists often make breakthroughs that are remembered as medical, technological or biological. Penned by chemistry professor Dr. Mark Griep and his painter wife Marjorie Mikasen, ReAction! points out that many examples of science in film are, in fact, misclassified as chemistry. Chemistry, the authors suggest, seems to occupy an interesting and unexplored niche in film; ReAction is the culmination of their years-long quest to understand how chemistry is portrayed in film. Intriguingly, the book is also an exploration of the history of chemistry as a discipline as reflected in the film, charting the course from the creation of the periodic table to chemical synthesis to modern drug discovery.

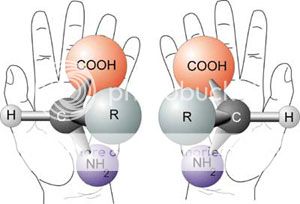

An important theme of the book involves the stark difference between the use of chemistry for “dark” or “bright” purposes. The authors’ view is that this duality underpins how society views science, as both great and terrible. One of the most well explored “dark” films of the book is Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. While the basic story is nearly universally known, the authors explore its film representations carefully, exposing both chemical and cinematic features of interest. The mirror-like duality between Jekyll and Hyde is used as a vehicle to confront the concept of chirality, which is the notion that molecules can have non-superimposable, mirror image isomers. As the authors undertake an exploration of the fictional chemistry of Jekyll’s formula, a stunning amount of chemistry is discussed. Jekyll’s formula contained “a white crystalline salt, blood-red liquor and a mysterious impurity.” The blood-red liquor, consisting of red phosphorous dissolved in carbon disulfide, introduces both nanoscience and stoichiometry. A discussion of the white crystalline salt centers on the observation that Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde’s author, Robert Louis Stevenson, likely suffered from a bleeding disorder. At the time, the best treatment and likely identity of the salt was a water extract of the ergot plant. This, the authors argue, means the unknown impurity was probably ergotamine. The historical developments surrounding ergot leads to a discussion of the beginnings of the pharmaceutical industry and introduces the concept of plant-derived drugs. Interwoven in the science is, of course, a discussion of the dark themes of self-experimentation and violence.

In this clip from the original classic 1912 silent movie, Boris Karloff transforms from Dr. Jekyll into Mr. Hyde (and back):

On the “brighter” side of things is Dr. Ehrlich’s Magic Bullet, a film that tells the story of the extraordinary scientist Paul Ehrlich. Ehrlich won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1908 for important contributions toward understanding the immune system, and also developed the first synthetic chemical treatment for disease. The authors describe how Ehrlich developed his “side chain theory,” which suggested that drugs and receptors interact in a specific way. This theory led Ehrlich to realize he could start with a “lead compound” that was weakly effective, or even toxic, and develop it into a powerful drug. Ehrlich started with the syphilis lead compound atoxyl and found a derivative, salvarsan, which was the first effective syphilis treatment. The magnitude of this discovery cannot be understated—Ehrlich’s methods ushered in the era of modern drug discovery and because Ehrlich was working at a time when the thought of injecting chemicals into humans to treat disease was unusual.

ReAction! gives a detailed analysis of the science and history of science related to many of the chemistry-related issues raised by the films it discusses. In fact, the science concepts introduced range from the very simple (stoichiometry) to the very complex (statistics); some of these concepts might be a bit difficult for a lay audience without a scientific background to grasp. However, the overall impression is that the authors have succeeded in using film as a vehicle to impart an incredible amount of science.

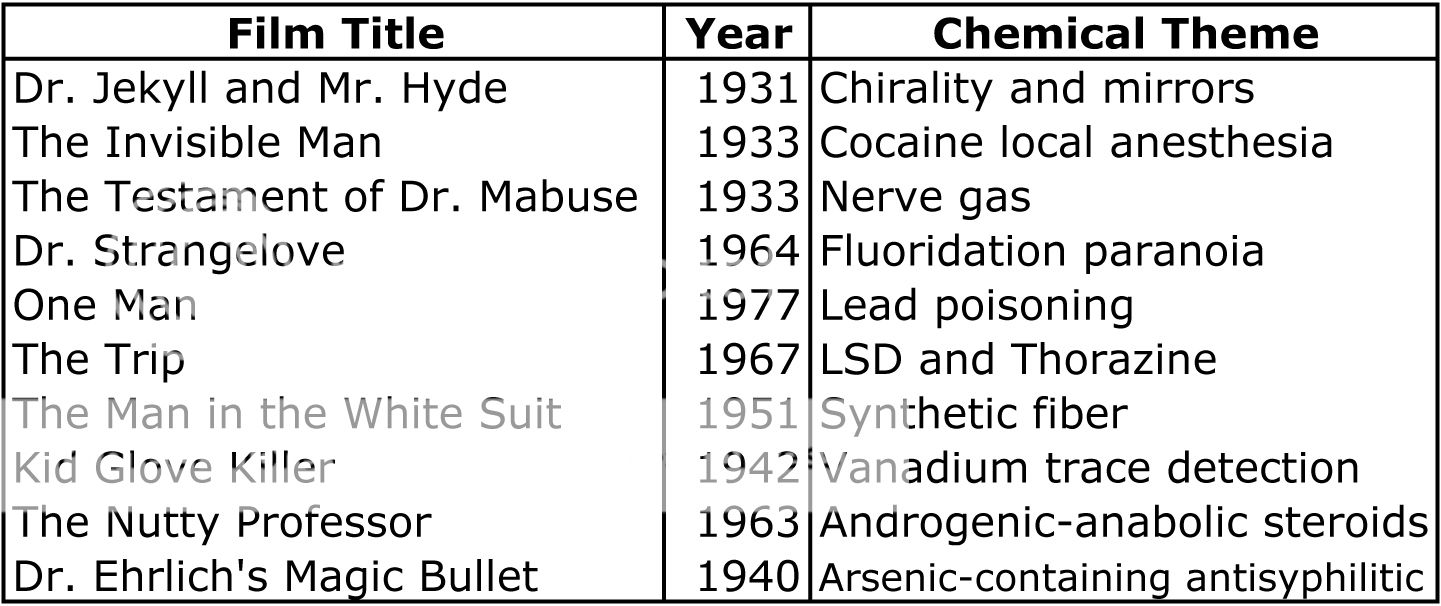

When I first picked up ReAction! and tried to think of examples of chemistry in film, I didn’t have too much success. Like the authors, I initially called to mind the myriad examples of technology, biology and medicine that are present in film. But after reading ReAction!, I’m sold on the idea that a rich tradition of chemical themes is present in film. At the end of the book, the authors give a list of 10 archetypal films that have chemical themes (table on the left). I’ve seen a few of these films, but now, I’m eagerly looking forward to watching the rest! And what about the chemistry of the alien microorganism in Andromeda Strain? I’m sad to report that ReAction! reveals that the mass spectral analysis in the film reports an elemental composition that can’t exist. After a bit of tweaking, the authors suggest that perhaps the alien life form could be alkaloid-like, and that the rock-like substance the life form arrived on could be a siloxane. It turns out the science behind that bit of Andromeda Strain wasn’t so sound; I guess you can’t have it all…

I caught up with Dr. Griep and Ms. Mikasen for an in-depth interview about their book, the portrayal of scientists in film, and the social outreach responsibility of scientists to enable better public perception of science.

Doug Fowler: I’m fascinated by collaborations between artists and scientists, which are often intriguing. Can you tell us how you decided to write ReAction!, and write it together?

Marjorie Mikasen: The first thing you have to know is that we are married and that we’ve been enjoying movies together since our first date. We prolong the movie experience by discussing them afterwards. Cut to 2000 when we rented the Elvis movie Clambake to take our new TV out for a spin. It was in Technicolor. Imagine our surprise when, one hour into the movie, Elvis was revealed to be a chemist on the run from his father’s oil company. The Elvis character was developing a superhard, superfast-drying varnish that he called GOOP. In a song, he sings its name as “Glyo-Oxytonic Phosphate”. We thought it was clever and funny that varnish is sometimes called goop and that the screenwriter turned the nickname into an acronym.

The impetus for the book started during the next few months. Mark is a chemistry professor at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Since he knows the chemistry naming rules, he wondered whether he could draw the structure for Glyo-Oxytonic Phosphate. He couldn’t. A few months later we watched the movie again in hopes there were other clues. Surprisingly, another character clearly enunciates its name as Glyol-OxyOctanoic Phosphate, a name for a structure Mark could draw after assuming “oxy” is short for “epoxy” and that the compound was designed in analogy to linseed oil, a real varnish. After watching Clambake, it seemed every third movie we rented had some chemistry in it. After collecting about 20 examples and searching for common themes among them, Mark decided to keep a list so he could search movie encyclopedias and online databases. We began purchasing movies with chemical themes. The tipping point for writing the book occurred when we realized the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation had a Public Understanding of Science program for movie-related projects. We were able to persuade the program officer that a book such as the one we wanted to write would be useful for chemistry instructors who wanted to inspire students to want to learn more chemistry. We were delighted that Oxford University Press wanted to publish such a book.

DF: How did your two very different points of view come in to play in considering how to approach the subject?

MM: After we decided to write the book, we had lunch together once a week to discuss it. Mark had already assembled about thirty common chemical themes found in the movies. In half the cases, chemists or chemistry was portrayed as a bad thing and, in the other half, they were portrayed as good. Keep in mind that Elvis used his new varnish to win a boat race, which allowed him to win the affection of his girlfriend and the respect of his father. It was easy for the two of us to select the six or seven strongest themes out of the thirty.

Mark Griep: Marjorie is an artist who is always playing ideas and themes off one another. In her consideration of other types of dualities, she saw that Jekyll and Hyde is the chemical embodiment of benevolence and darkness so it quickly became the book’s overarching theme. With that in place, we developed the structure of five dark themes (Jekyll & Hyde, Invisible Man, chemical weapons, bad chemical companies, and illegal drug use) followed by five bright themes (chemical inventors, chemical detectives, chemical instruction, benevolent chemical researchers, and drug discovery). The actual order of the chapters was deliberately chosen to emphasize the dualities between the two halves of the book. For instance, the difficult-to-detect invisible man is the second chapter on the dark side while chemical detectives are the second chapter on the bright side.

DF: I read that the book was funded by an Alfred P. Sloan grant for the Public Understanding of Science. Is the book part of a lifelong interest in public outreach?

MM and MG: Artists and Scientists are always educating the public about their work. Both of these fields are at the edge of society’s quest for understanding so it is important for their practitioners to discuss their exploration of the frontiers. This book isn’t our first collaboration but it does represent our biggest co-venture. With our book, we wanted to use feature films to show the wider public how chemistry is an integral part of our society and how real chemistry ended up in the movies. Like it or not, movies are mediators of public understanding. They selectively portray things about society and, because of their wide dissemination, they have the power to influence many people. It is important for our society to have a scientifically literate public and we thought this would be a fun way to generate a thirst for more scientific knowledge.

DF: How did you decide to focus on chemistry found in movies as opposed to more mundane but realistic venues?

MM: Mark found that students responded to the chemistry in movies much better than they responded to the chemistry in news reports. When Mark taught General Chemistry for the first time, he gave the students a 600-word writing assignment. They were supposed to write about the chemistry in a recent newspaper or news magazine. Such an exercise promotes deep learning because the student has to process the issues and decide what is important. Mark was surprised that only 60% of the students completed the assignment and disappointed that some of them wrote about topics such as vaccines, supernovas, etc. without mentioning their chemical aspects. Mark decided he needed more control over the student choice of subject material. By that time, he had a list of based-on-a-true-story movies that were chemically inspirational. The next two times Mark taught General Chemistry, he projected two of these movies and had the students write about one of them. It was a great success; 95% of the students completed the assignment and the quality of writing was vastly superior. To make it easier for other instructors to repeat this blockbuster of an idea, we published a summary of it in the Journal of Chemical Education that included a list of the chemical and societal themes for 12 movies based on true chemical stories.

DF: Throughout the book, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde was the most discussed prototype movie. I wondered how you made the decision to make that movie central to the book. Is it a movie you particularly like or have a personal connection with, or is it just because it’s such an old, publicly recognizable movie involving chemistry?

MM: Like everyone else, we knew the phrase “Jekyll and Hyde” before we ever read Stevenson’s 1886 book or saw one of its many movie adaptations. The first dramatic version we watched was the 1931 version starring Fredric March. His transformation scene is enjoyable because it is theatrical. You can imagine it would be an interesting challenge for an actor to change personalities to match his appearance and March does a great job.

Even though Jekyll is shown mixing chemicals, Mark was intrigued that the transformative formula was not described in enough detail to know what it was supposed to represent. Stevenson’s original story describes a contaminant in a white powder that changes color when it is added to a blood-red solution but it doesn’t name the powder or the contaminant. Seeking other avenues to pursue, Mark contacted Stevenson scholar Richard Dury to find out whether any scholarship had been done on this topic. Dury told him that Stevenson’s wife Fanny had written a letter immediately before Stevenson wrote the novella in which she says he suffered from hallucinations after being treated with an ergot extract. This episode appears to have inspired Stevenson to write the story. Mark then discovered that ergot fungus is a pharmacological toolbox containing compounds to constrict arteries but also compounds to cause hallucinations. It seems that Stevenson’s doctor had treated him with the ergot extract to stop the bleeding in his lungs. The hallucinogenic side effect was caused by a minor component of the extract. This led Mark to conclude what Jekyll’s compound might be.

MG: When we

began preparing to write our book, Marjorie pointed out that Jekyll’s physical transformation was the external manifestation of his personality change. Mark responded that these transformations link it to chemistry because chemistry is about the study of matter and its transformations. Marjorie suggested using Jekyll and Hyde as the overarching theme for the book because the character of Jekyll/Hyde transforms between a dark side and a bright side, giving us a way to describe the positive and negative depictions of chemistry in the movies as a whole. As we further honed the chapter structure of the book, we knew there were going to be many echoes of the Jekyll and Hyde. In fact, anyone who self-experiments in the movies is following in the footsteps of Dr. Jekyll.

DF: My favorite movie about scientists is Andromeda Strain, because it portrays a relatively realistic view of who scientists are and what they can accomplish. However, in most movies, scientists and their abilities are rendered in a much more dramatic, unrealistic style. How do you think this affects the public’s view of scientists?

MM and MG: It is important for the pace of a feature film to use stereotypes. It helps the audience get into the story quickly so they can watch the interaction between the characters rather than the actors.

How do you recognize a chemist in the movies? When the chemist character is an inventor, he wears a white lab coats as he handles beakers and flasks while solutions bubble in glassware behind him. He often accidentally synthesizes a compound that solves a personal problem. These sorts of films are still being made and show an archaic view of the modern laboratory where nearly everything is on a small scale and instruments are used to analyze the material.

When the chemist character is a criminologist, he or she wears a white lab coat while using microscopes and other instruments to examine the minutiae of a crime scene. The solution to the crime, however, usually relies upon intuition. Chemically determined facts are used to eliminate possibilities. These chemists understand chemical analysis and criminal behavior.

When the chemist character is a researcher, he or she searches for a solution to a problem affecting other people. Most of the research chemists are based on true stories and aren’t as popular as the above two types of movies. They tend to move at a slower pace because the nature of the science and tools has to be explained in an engaging but understandable way. They are usually biographical pictures.

These three chemist stereotypes give us the shorthand view of what fictional chemists look like and their motivations for doing research. All three types are obsessive about their work, which is not too far from reality. In general, we think these stereotypes are benign.

DF: Does it help or hurt the cause of publicizing science?

MM and MG: Let’s just say we will always need good educators to clear up these sorts of misunderstandings. It would be great if we could teach people to be optimistically skeptical when they encounter new claims. Movies and television are problematic in that viewers are able to see that something works with their own eyes. Even if they know it is “only a movie” or “only TV”, the image has entered their memory cells. If it is reinforced in any way, they will remember the image long after they’ve forgotten its source. As long as academicians keep putting out good information in reliable locations, the public will have somewhere to look when they are seeking answers.

Another answer to this question is that it helps and hurts. Consider the “CSI Effect” that trials have been experiencing in recent years. It seems that juries are demanding more sample analysis than the investigators carried out. For instance, juries might want to know why DNA analysis wasn’t performed on all samples at the crime scene. The people serving on juries don’t realize how expensive or time-consuming it is to run each analysis. The positive spin is that juries want to have all the dots connected by solid scientific methods. It is great they want to rely on physical evidence rather than on unreliable eyewitnesses.

DF: Your book touches on the fact that chemistry has also changed a lot over the course of recent history. Can you expand on how these changes are reflected in the portrayal of science and scientists in the movies?

MM and MG: The portrayal of chemists and chemistry in the movies has become much more realistic in recent years. Since comedies often rely much more heavily on stereotypes, they mirror their time really well. In the 1930s comedies such as The Chemist (1936) starring Buster Keaton and Violent is the Word for Curly (1938) starring the Three Stooges, the chemist characters are professors who wear a black mortar boards and capes rather than white lab coats. Of course, these slapstick artists were making fun of the arcane knowledge produced by higher education. Flash forward to the 1990s when we had The Nutty Professor (1996) starring Eddie Murphy and Flubber (1997) starring Robin Williams. There is still too much glassware and these inventors are still University professors but they use correct scientific terms, have appropriately outfitted laboratories, and colleagues who interact with them realistically. These 1990s comedies were made for the youth market, none of whom would know whether these things were correct or not. These comedies use the reality of factual chemistry and its accoutrements to launch their satirical fantasies.

DF: Chemistry is often defined as “the central science,” and chemistry seems to influence many different fields of science. As such, it’s often hard to know just what qualifies as chemistry. How did you draw this distinction when classifying movies?

MM and MG: The basic rules of classification are simple. It is the exceptions that are complex. The two simple rules for inclusion are: 1) a character is identified as a chemist, or much more rarely, a biochemist, geochemist, etc.; and 2) one of the characters mentions an element, isotope, compound, or simple mixture. The characters are further categorized according to the type of chemistry they do. The chemicals are usually categorized by name. Overly common chemicals, such as gold and water, are not tracked even though one is an element and other is one of the most important compounds on Earth. On the other hand, when gold plays a role in a movie that has other chemical features, the gold is tracked. For example, munitions maker Tony Stark (Robert Downey Jr.) isn’t an iron man for very long in Iron Man (2008). For most of the movie, he’s actually gold-titanium alloy man whose suit is powered by a plutonium-powered arc.

DF: Aspects of science and the scientific establishment have come under increasing attack by various organizations and individuals. Public distrust of science and scientists seems to be increasing, whereas scientific literacy has decreased. What role do you see movies and other media playing in these trends?

MG: Before I answer the question, I’d like to disentangle a few issues. The National Science Foundation published an interesting study in 2002 titled “Science and Technology: Public Attitudes and Public Understanding”. There have been many changes since 2002 but the public probably still believes overwhelmingly that scientists wear glasses and white lab coats while working with beakers and flasks for endless hours alone in the lab. On the other hand, the public also says that “scientist” is the second highest prestige occupation (56% enthusiasm), just behind “doctor” (61% enthusiasm). The public respects science although they don’t necessarily want to be a scientist. The NSF article also noted the public thought economic and educational issues were more important than global warming. It is not really a contest to determine which of these three topics is of greatest interest to the public but it does say most people are most interested in issues that touch closest to home. Knowing that the average global temperature is slowly rising is only part of the equation. People want to know what they can do to adapt now in a way that doesn’t harm them economically. I don’t think that message has been communicated at all.

I agree that scientific literacy has decreased but there are many factors at play. One is that people rely less on their memories today and more on the internet for factual knowledge. For instance, you can learn an awful lot by reading Wikipedia, but you should always verify the cited sources. Another factor is the sometimes incredible expectation raised by the science in TV shows, movies, and news articles. As authors of a book about chemistry in movies, we see this as a great opportunity for a teaching moment. It is one of the main reasons we wrote our book. Yet another significant factor is that science is taught as a collection of facts rather than as a method of discovery. There are many ways to solve the latter problem. One is to educate students how to develop and test their own hypotheses. At first, students would reproduce well-known phenomena but they would develop an appreciation for proper methodology and the power of science to test a hypothesis. These hands-on experiences could be coupled with student-centered instruction where groups of students work together to answer a series of factual questions. In this way, the students take possession of the knowledge. Finally, introductory science material should be presented as a series of tested hypotheses rather than as building up from basic established principles. Introductory courses should explore local and global issues so that students can see that science is being used to address the biggest questions of our time. All of this would help students experience the wonder of science, where your understanding of something changes after you learn something new.

It may seem like a contradiction to what I have just written but feature films can be used to help teach chemistry. The movies in our book were selected because they present chemistry in a social context, even when the movie is fictional. The dozen movies that are based on true stories about chemists can be shown to students in their entirety. The chemist character’s social hurdles are emphasized along with the scientific ones. The assignment could be to answer a series of factual questions or to write a report with citations that emphasizes the chemical aspects presented in the film. There are often factual inaccuracies or time compressions that gloss over some relevant details. Besides these biographical movies, there are several dozen movies with a 2- to 5-minute sequence in which the chemistry that drives the narrative is explained. I call these the scientific-explanation scenes. They tend to be funny or exhilarating. In our book, the cue time for each of these scenes is indicated in the narrative summary, along with descriptions of the real chemistry upon which it is based.

Douglas Fowler, PhD is a National Institutes of Health Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Washington working to implement new technologies to investigate protein sequence/function relationships. Although more of a biologist these days, he got a BA in chemistry and philosophy at Northwestern University and a PhD in chemistry at The Scripps Research Institute.

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and pop culture. Follow us on Twitter and our Facebook fan page. Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.