ScriptPhD.com is extraordinarily proud to present our first ever Science Week! Collaborating with the talented writers over at CC2K: The Nexus of Pop Culture and Fandom, we have worked hard to bring you a week’s worth of interviews, reviews, discussion, sci-fi and even science policy. We kick things of in style with a conversation with Professor Malcolm MacIver, a robotics engineer and science consultant on the SyFy Channel hit Caprica. While we have had a number of posts covering Caprica, including a recent interview with executive producer Jane Espenson, to date, no site has interviewed the man that gives her writing team the information they need to bring artificial Cylon intelligence to life. For our exclusive interview, and Dr. MacIver’s thoughts on Cylons, smart

robotics, and the challenges of future engineering, please click “continue reading.”

Questions for Professor Malcolm MacIver

ScriptPhD.com: Your first Hollywood science experience involved consulting for a sequel of the 1980s cult classic Tron. What was it like to dive in from the Northwestern School of Engineering onto a

set and work with screenwriters? What were some of your first impressions?

Malcolm MacIver: It was fascinating to learn a bit about how these huge expensive projects are structured. One specific thing I wanted to know more about was the role of writers in movies versus in TV. I had been told by friends in the industry that writers are typically less prominent players in movies than in top TV shows, were they can have considerable power. Consistent with this, we (the scientists who met with the Tron folks) were not introduced to the writers, who I believe were in the room taking notes, while we were introduced to all the other major players (director, producer, etc). I was also very curious to see how the group of scientists that I was a part of would interact with the movie makers. The culture gap is obviously huge, big enough for massive misunderstandings to blossom during superficially neutral discussions. During our meeting, our approach to the folks involved with the movie varied

from inspired to less admirable attitudes. The less admirable attitudes seemed to arise from the mismatch between the importance scientists can place on their own endeavors, relative to their endeavor’s importance to story telling.

An anecdote I like along those lines is about how the astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson complained to James Cameron that when Kate Winslet looked up from the deck of the Titanic, the stars in the sky were in the wrong position. I liked Cameron’s response, which was “Last I checked the film’s made a billion dollars.” People love the story, not the positions of the stars above the Titanic. We all tend to overemphasize the importance of the thing we are closest to, and it’s a problem that scientists need to be especially attuned to in these contexts.

SPhD: You are now a technical script consultant for Caprica, the television prequel to Battlestar Galactica, providing insight into things like artificial intelligence, robotics and neuroscience. To date, what has been one of your biggest contributions to a final written episode that otherwise wouldn’t have made it in to the storyline?

MM: One of the themes of my research is understanding the ways in which intelligence is not just all about what’s above your shoulders. Nervous systems evolved with the bodies they control—the interaction is extremely sophisticated, and stubbornly resists our attempts to understand it through basic science research or emulation in robotics. Representative of this fact is that we now have a computer that can beat the world chess champion—a paragon of an “above the shoulder” activity—while we are far from being able to robotically emulate the agility of a cockroach.

One of the things we’ve learned about the cleverness that resides outside the cranium is that things like the spinal cord are incredibly sophisticated “brains” operating sometimes without much input from upstairs. Through some old experiments that are better not gone into, scientists showed that animals can walk with little brain beyond the parts that regulate circulation and breathing and their spinal cord. This is because the spinal cord can do most of what we need for basic locomotion without any input. The point is that control of the body is distributed—it doesn’t just live in the brain. The lesson hasn’t been lost on robotics folks; for example, Rodney Brooks popularized an approach called “subsumption architecture” based on this idea. So – back to Caprica: For episode 2, “Rebirth,” the show needed some explanation for why the metacognitive processor was only working in one robot. The real reason, as we know, is that only one had Zoe in it; but the roboticists were being pressed by Daniel Graystone as to why it wasn’t working in others. The idea that I gave them, which they used, was that it was because this particular metacognitive processor had distributed its control to peripheral subunits. Because of this, it had become tied to one particular robot. It’s an idea straight out of contemporary neuroscience and efforts to emulate this in robotics.

SPhD: To me, one of the most fascinating directions of the show is the idea that the first Cylon prototype was born of blood, in this case Zoe Graystone, and because of that, carries sentient emotions and thoughts. What is the fine line between a very smart, capable robot and an actual being?

MM: To vastly oversimplify things, you can imagine a gradation in “being” from a rock to a fully sentient self-aware entity. Some of the differentiators between the rock and you include things like the impact of others on how you think about yourself. For example, categorizing a rock as a particular kind of rock has no effect on the constitution of the rock. This isn’t so for self-aware creatures: once a person is labeled a child abuser, it actually affects the constitution of the person so labeled. People treat child abusers differently from non-child abusers. People who are categorized in this way suddenly see themselves differently; and those who were victims do so as well. The philosopher Ian Hacking, who I studied with during my Masters in Philosophy at the University of Toronto, called this the difference between “Human Kinds” and “Natural Kinds.” Another differentiator is that, for what you refer to as an “actual being,” there is a sense of self-interest in continued survival. Because of this, such a being is susceptible to being harmed, and may also therefore have what an ethicist would call “moral worthiness.” Moral worthiness in turn imposes certain obligations in regard to ethical treatment. For example, returning to the rock, we wouldn’t say we harm a rock when we explode it with dynamite, and we wouldn’t accuse the person who did the blowing up of unethical behavior (certain stripes of environmentalism would differ on this point). Unlike a rock, all animals exhibit an interest in self-preservation.

A very smart and capable robot can be imagined which is not affected by how it is categorized by others, and does not have an interest in self-preservation. So, it would fall short of at least those criteria for full-on “being.” But, there’s a lot more that can be said here, of course.

SPhD: What aspect of the Cylon machine and their story, which is now at the heart of Caprica, do you find the most captivating, either as a viewer or a robotics engineer?

MM: The scenario of our inventions eventually becoming so complex that they begin to have an interest in self preservation, and thus can be harmed (and so may start to be candidates for ethical treatment), is one I’ve thought a lot about in the past. It’s a key theme of the show, too. That’s one aspect that fascinates me about the show. The other is the play between the different kinds of being that Zoe has—from avatar-in-a-robot, to avatar-in-virtual reality, to “really real.” It’s a fun fugue on the varieties of being that raises good questions about the nature of existence and mortality, among others.

SPhD: In your latest post for the Science in Society blog, you explore the theoretical question of whether the United States (or any country, for that matter) could develop a Cylon type of war machine. Do you feel there is a distinct possibility the military might ever pursue this option and how might it impact warfare strategy?

MM: I’m going to explore that in my next few posts—and I’m still formulating my thoughts. In their initial development, a more realistic metaphor for how such robot warriors will work with us is something like a dumbed-down well-trained animal, willing to follow commands but without much of a sense of what to do if something gets in the way, and little recourse to things like flexibly generating new behaviors like a real animal does. But I can’t foresee any significant barriers to the development of autonomous robots with more of the attributes of a fuller kind of being I mentioned to above. I feel the more relevant question is whether this is on the order of 10 years away, or a hundred. Once it happens, the question will then be whether the global community recognizes military applications of this technology as a potential threat in need of careful control, like nuclear arms, or not. That’s all for now – for more you’ll have to visit my blog!

SPhD: During last year’s World Science Festival, we covered a really interesting panel called Battlestar Galactica: Cyborgs on the Horizon, which included a cross-section of engineers, ethicists and Battlestar actors discussing artificial intelligence, robotics, and the capabilities of modern engineering, which in some cases are very impressive indeed. In your opinion, what is one of the most significant or promising advance in robotics of the last few years?

MM: The maturing of what is sometimes called “probabilistic robotics.” This approach is what allowed the autonomous car Stanley to win the DARPA Grand Challenge, the challenge to have a vehicle drive itself with no human involvement over a challenging course in the desert. The basic idea is that while traditional robotics was concerned with making precise motions based on very well characterized inputs, what we need for robots to work in the real world is ways to handle the massive array of noisy and uncertain signals that are typically available to guide behavior. There are approaches from probability and statistics for doing this well. These approaches are integral to making robots have greater sensory intelligence. My own laboratory has developed a new kind of sensory robot using this approach, and it works very well.

SPhD: I have previously argued that television and film do more for promoting science by incorporating small, accurate pieces into an overarching story rather than basing an entire story on an unsustainable or far-reaching scientific concept. Thoughts?

MM: TV and film, when it is successful, is about telling a captivating story. The elements of good story telling (emotional connection to the characters, humor, insight into what it is to be human) have little in common with the elements of a good scientific concept (testability, explanatory power, coherence with the rest of what we know). So, yes I’d agree. Trying to do more than incorporate small bits is going to lead to your audience feeling like they are getting a lecture rather having a story shared with them, and no story teller should do that. Documentaries are an interesting hybrid, though—you need a good story, and if it’s about science, a good bit will be on the concepts. How to make that exciting and not spin out into yawn-provoking pedantry is quite the trick.

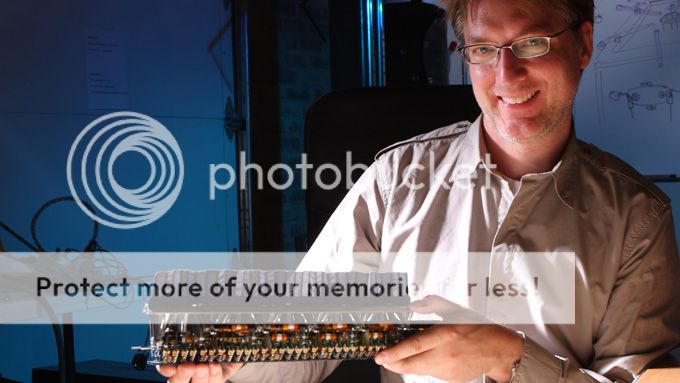

Malcolm MacIver, PhD, is a professor at Norwestern University with joint appointments in the Biomedical and Mechanical Engineering departments, and an adjunct appointment in the Department of Neurobiology and Physiology. He received a B.Sc. and MA at the University of Toronto, and a PhD in Neuroscience at the University of Illinois in Urbana-Champaign in 2001.

~*ScriptPhD*~

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development.

Follow us on Twitter and our Facebook fan page. Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

]]>I’m honored to be joining ScriptPhD.com as an East Coast Correspondent, and look forward to bringing you coverage from events in such exciting areas as Atlanta, Baltimore, and New York City – as well as my hometown of Washington, DC.

And to that end, here is a re-cap of the World Science Festival’s panel “Battlestar Galactica: Cyborgs on the Horizon.” For anyone interested in the intersection of Science and Pop Culture, I cannot promote this event enough. In addition to the panel I’ll be describing, some of the participants included Alan Alda, Glenn Close, Bobby McFerrin, YoYo Ma, and Christine Baranski from the entertainment sector. Representing science were notables like Dr. James Watson (who along with Francis Crick was the first to elucidate the helical structure of DNA), Sir Paul Nurse (Nobel Laureate and president of Rockefeller University), and E.O. Wilson (who is celebrating his 80th birthday in conjunction with the festival).

However, it’s time to return to the subject of this post – BSG and Cyborgs. To read more about the discussion at the intersection of science fact and science fiction, please click “Continue Reading”.

Regretfully, the 92nd Street Y in New York City prohibits the use of any sort of recording equipment, which was not noted on their description of the event or on their policy page, but which I discovered as one of their staff came to scold me while I was testing my camera prior to the inception of the event. So while I took comprehensive notes, I was unable to record the panel in order to provide a full transcript. Nor did I get any photos.[note: and believe me, the reactions shots of Mary McDonnell and Michael Hogan to the cutting-edge science they were showing was worth the price of admission, and would’ve made fabulous photos!]

Faith Salie was the moderator for the event. Geeks may know her best as Sarina from Star Trek: Deep Space Nine. She’s also a Rhodes Scholar, host of the 2008 and 2009 Sundance Festival, and hosted the Public Radio International Program Fair Game. Her knowledge of Battlestar Galactica was impressive, and she’d also done a great deal of background research on the issues related to robotics and artificial intelligence, which allowed her to keep the conversation going, and give fair time to both the science and the scifi.

The science panelists were Nick Bostrom the director of Oxford University’s Future of Humanity Institute and co-founder of the World Transhumanist Association which promotes the ethical use of technology; Hod Lipson, director of the Computational Synthesis Group and Associate Professor of Computing & Information Sciences at Cornell University, who has actually developed self-aware and evolutionary robots; and Kevin Warwick a professor of Cybernetics at the University of Reading in England—unlike Gaius Baltar, Dr. Warwick has a chip in his head. In anticipation of this event, Galactica Sitrep interviewed both Dr. Lipson and Dr. Warwick, and they are interesting reading for more insight into these scientists’ perspectives.

The BSG panelists were Mary McDonnell and Michael Hogan. Faith Salie very aptly introduced Mary McDonnell as “gorgeous” before briefly covering her film credits outside of Battlestar. Vis-a-vis Michael Hogen’s introduction, we learned that he also has X-Files to his credits. [A fact which is sadly missing from his IMDB credits, leading me to wonder which episode??]

The moderator opened the discussion by asking Mary McDonnell and Michael Hogan what life was like after BSG. Mary McDonnell pretended to sob, before acknowledging that “life after death is actually quite wonderful.” She went on to say that dying wasn’t so bad and that she enjoyed being the only actress ever to die first and then get married. At the audience laughter, she then smiled and said she was pleased to see that we “got it” as she made the same quip somewhere else recently and it went over the audience’s head. She pantomimed Adama putting his ring on Laura’s finger after her death in the finale and described the scene as “beautiful,” and her work on BSG, in general as “so compelling.”

She said she was going to miss the cast including “Mikey,” (Michael Hogan sitting next to her) and would miss the direct connection with the culture, and so she was excited by events like the World Science Festival Panel that would allow that connection to continue. She also said that the “fans are the best,” and applauded the audience to which Michael Hogan emphatically joined in.

Michael Hogan’s answer to the same question was that it was very good to leave when it did and “have it sitting the classic show,” and that the experience would stay with him for the rest of his life. He was then asked to set up the premise of the show for those few in the audience that had not seen it. His answer was

In a nutshell, Battlestar Galactica is about an XO who befriends a man who becomes the commander of the Battlestar Galactica and the trials and tribulations of their relationship.

After the audience stopped laughing, he gave the more mainstream description of Battlestar being about the war between the Cylons and humanity and the series opening at the point that the Cylons have just nuked the twelve colonies where humanity lives.

This allowed the moderator to segue into clips from both the Miniseries and the Season 2 episode “Downloaded” where we saw the character, Six, explaining that she is—in fact—a Cylon, and then going through the downloading process.

Following the clips, the discussion turned to the scientists in the panel, who were asked to answer the question: What is a robot?

Kevin Warwick explained that the term “robot” came originally from Karel Čapek, a Czech writer who envisioned robots as mindless agricultural workers. It’s now come to be used much more broadly for that which is machine or machine-like, and that in current usage there’s not much difference between a robot or a cyborg [Note: There are those that would vehemently disagree—a common distinction between the two is that cyborgs are a mixture of both the non-living machine and the organic]. Hod Lipson said that trying to pin down the meaning of that term was a moving target, much like trying to define artificial intelligence.

The panelists went on to talk about who all robots and artificially intelligent systems try to imitate something living—from the primitive systems such as bacteria, to more complex animals as dogs and cats, and now ultimately to humans.

The idea of artificial intelligence and robots that can think for then explored. Hod Lipson said that for the longest time the ability to play chess was recognized as something that was paradigmatically human, but we do now have machines that can easily beat a human at chess. As such the ultimately goal of artificial intelligence and machines that can reason gets moved further and further.

From there, the discussion moved back to Battlestar Galactica, and Faith Salie asked Michael Hogan how he felt upon learning that he was one of the Final Five. They then showed a clip from the Season 4 episode “Revelations in which Michael Hogan’s character, Saul Tigh, discloses his identity as a Cylon to his commanding officer and long-time friend, Bill Adama.

Michael Hogan explained that he disagreed vehemently with that decision, but that it was not something that he could talk the executive producers, Ronald D. Moore and David Eick, out of. He said that for a long time on set there had been joking about who the final five were going to be—knowing that they were going to be picked from those characters that were already established—and had initially thought it was another bad joke. He also said that he’d seen an internet poll at one point asking who fans thought—among all the characters, both large and small—were the final five and he was second from the bottom, while Mary McDonnell was near the top.

When asked about researching his role as XO and later Cylon, Michael Hogan said that researching and getting into a character is part of what attracted him to the job of acting. This led to a side quip about it being a lot of fun to research a cranky man with a drinking problem. More interestingly, he was then asked: How do you research being a robot?

His answer was that he approached it like mental illness. He said he took it as a given that Tigh would already be living in chronic pain as a result of the torture he’d undergone on New Caprica and a functioning alcoholic, so that when he first started hearing the music (that activated him as a Cylon), it wasn’t necessarily a big surprise; it was just one more thing.

It was only after he had the realization in the presence of the other three Cylons that things fell into place, and then it was terrifying for him. He went on to say that Tigh, if not the chronologically oldest person in the fleet [which I guess means counting from the time at which they “awoke” with the false memories on Caprica] definitely had the most combat experience, and as a Cylon was therefore a “very dangerous creature.” To illustrate that, he then described the scene in which Tigh envisioned turning a gun on Adama in the CIC.

Kevin Warwick picked up on this thread and said that this was, “taking your human brain, but with a small change, and everything is made different.” Michael Hogan agreed.

In turn, the moderator then turned the discussion to the work Dr. Warwick is doing in using biological cells to power a robot. In essence, Dr. Warwick has developed bio-based AI. He harvests and grows rat neural cells and then uses them to control an independent robot. At this point in his experiments, he said, they’re only attempting simple objectives such as not getting it to bump into walls. However, as the robot “learns” these things, the neural tissue powering it shows distinct changes indicating that pathways are being developed.

He said he hopes that this research might some day lead to a better understanding of human brains and potential breakthroughs in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s research. There is a video of this robot in action at the London Telegraph story “Rat’s ‘brain’ used to control robot. Other external articles include Springer’s “Architecture for the Neuronal Control of a Mobile Robot” and Seed Magazine’s “Researchers have developed a robot capable of learning and interacting with the world using a biological brain.”

The description of these neuronal cells led then to a discussion of the Cylon stem cells used to cure Laura Roslin’s cancer in the episode, Epiphanies. Mary McDonnell informed the audience that the story line original sprang from what, at the time, was the U.S.’s resistance to stem cell research. The moderator then decided to bring a little humor to the discussion by saying, “So, Laura’s character as near death, but your agent finally worked out a contract.”

Mary McDonnell laughed and said, yes, she was near death but she finally decided to stop pushing for a trailer as big as Eddie’s [Edward James Olmos] realizing that “no one gets a trailer as big as Eddie.”

Returning to the discussion of the plot, Mary McDonnell noted that what really fascinated her about this storyline was Baltar. She said that it was the first time we saw “the beginnings of a conscience” in him, and that as a result of that he took “profound action.” She then further described the course of cure based in the stem cells from a half-human/half-Cylon fetus, and concluded with saying, “Not to say I got up the next day and became a Cylon sympathizer . . .”

The panel discussion then segued to a discussion of the work being done by Hod Lipson on robots’ abilities to evolve—in a Darwinian sense—and to breed. Using modeling and simulation tools and game theory, Dr. Lipson is creating robots who self select based on desirable traits and from generation to generation become stronger, more mobile, and better adapted to their environments. His slides included a reference to the Nature article “ Automatic design and manufacture of robotic lifeforms.”

Dr. Lipson noted that many of the parts used in these robots are created using 3-D printing, which is, in itself a rather new and exciting technology that really excited not only the moderator, but also Michael Hogan and Mary McDonnell. What wasn’t discussed, is that beyond allowing robots to design their own parts, this technology has a lot of practical applications. One of those that has the greatest potential to positively impact people is that of prosthetic socket design.

In order for the robots’ evolution to proceed more swiftly and realistically, Dr. Lipson explained that he’s given them the ability to self-image. Yes, the robots are SELF AWARE. He showed a video (a variant of which can be found from an earlier talk on You Tube) which showed a spider-like robot experimentally moving its limbs and as it did so, developing an idea of what it looked like. At each generation, the robot’s idea of what it looked like got more and more accurate, and its ability to move grew more and more precise.

The researchers then removed one of the robot’s four limbs, and Dr. Lipson described how the robot became aware that its limb was missing and even adapted to walk with a limp This elicited sounds of sympathy from both the audience and Mary McDonnell until both the audience and Ms. McDonnell realized we were sympathizing for a machine. If this doesn’t show how the very blurred the line has become, I’m not sure what does!

Dr. Lipson’s other research involves robots that can self replicate. His slides for this portion referenced the Nature article, “Robots: Self-reproducing Machines.” These robots are modular and when given extra modules will, rather than adding to their own design, create a copies—exact replicas. (Yes, perhaps Battlestar Galactica wasn’t that far from the mark when it posited that “there are many copies.”) The reaction of both the non-science panelists and the audience to the video that was included of the tiny robots using extra building material was really that of astonishment. Michael Hogan spent much of this discussion watching the monitor with his mouth agape in wonder.

To the amusement of about half the room, the moderator than asked Dr. Lipson if perhaps he could “design fully evolved robots so that the creationists have something to believe in.” While an easy laugh, it also does raise the question that follows. While the moderator asked posed it as, “Are we in a paradigm shifting moment,” it could easily also be tied back to the Battlestar Galactica universe and Edward James Olmos’ (as then Commander Adama’s) speech in the miniseries when he suggested that perhaps in creating the Cylons man had been playing God.

The panelists noted that machine intelligence does not have the same constraints as human intelligence. A human brain consists of, as one panelist put it, “three pounds of cheesy grey matter” and performing functions takes 10s of milliseconds. A computer chip is already orders of magnitude faster. When asked to pinpoint the point at which human-level AI could be accomplished, the panelists were originally reluctant to give a time frame, though with great reluctance acknowledge that it could happen within our lifetime.

Hod Lipson suggested that the next step—that of superhuman AI—would be substantially shorter than the first step of accomplishing human-level AI.

This discussion then naturally led back to Battlestar Galactica’s dystopic view of a potential robot-led uprising. After all, if, as the scientists on the panel think that the accomplishment of an artificial intelligence that is smarter than humans is not only possible, but probable, what is the likelihood that this artificial intelligence is going to want to do what its human creators tell it to do?

The panelists dodged that question, saying that they found that part of the science of BSG highly unrealistic

It’s entirely improbable that [the Cylons] would begin by killing off all the ugly people.

They then discussed issues relating to the internet and networking relative to the evolution of robotics, which was another area that was of grave concern in the universe of Battlestar Galactica. The scientists all agreed that that aspect of BSG and Adama’s fear of networking was highly realistic. They said that the driving force for robotic evolution was really the software, because at this point given that many computers have multi-core processors independent computers, in some ways have mini-networks inside them. They also said that networking itself is a highly vague concept and that “it’s not like you can just ‘turn off’ the internet.”

A clip from the third season episode “A Measure of Salvation” which showed the discussion among the characters surrounding the potential for Cylon genocide vis-a-vis a biological weapon then followed. Mary McDonnell noted that in addition to the many ethical questions that were raised relative to whether or not one can realistically commit a genocidal act against “machines,” one of the remarkable points of that episode for her, was the scene that followed wherein Adama turned the choice over to Roslin (parenthetically, Mary McDonnell noted “as he often did with difficult decisions”). She said that it was fascinating to her to later watch Laura’s (parenthetically, again, she said, “her own”) face during that moment she ordered the genocide—because although Laura was did what she did for the same “reason she did almost everything” in making a choice for survival, that underneath that she could see a “pure cynacism”—the type of which is at the root of any difficult decision that you “ethically disagree with but do it anyway.”

When asked by the moderator whether they were given the opportunity to provide feedback on the direction their characters were going, and Mary McDonnell and laughed and said they were “the noisest bunch of actors.” She said that it was particularly difficult for her at the beginning of the series because she had to shift a lot of her point of view in order to adapt to Laura Roslin’s own changes and many of the more “feminine aspects had to shift into the back seat.” She described a point at which she and [executive producer] David Eick were trading angry emails, and [executive producer] Ronald D. Moore had to butt in and send them back to their respective corners.

She followed that by saying that she’s never before “had the privilege to be inside something that engendered so much discourse.” Both she and Michael Hogan said that while they rarely connected with the audience outside of special events, that Ronald D. Moore was profoundly aware of the audience’s reaction and feedback and did sometimes take that into account, so that there was truly a “collective aspect” to the show. And they both again applauded the fans and the audience.

From that, the discussion then returned to the original subject of the clip, and that of “robot rights,” and whether it was possible to provide “rights” to robots and whether they had subjective experiences and a sense of self upon which the foundation for such a discussion should be lain. Dr. Lipson said he did envision a day where “the stuff that you’re built out of is no more relevant than the color of your skin,” and that in many cases “machines are not explicitly being programmed and to that extent it’s much closer to biology.”

Dr. Bostrom, who served as the ethical check necessary to balance the scientists’ curiosity cautioned against the “unchecked power” of the sort that comes with this technology after so the other two scientists suggested that given that AI lacks a desire for power, that it is not something to be generally feared.

Dr. Bostrom further noted that all self-aware creatures have a desire for self preservation, and that perhaps most relevant to the discussion of BSG was the use of AI in military applications, where the two goals were “self preservation” and “destruction of other humans.” He suggested that the unpredictability of evolved systems might be the very reason not to do it.

He noted that the “essence of intelligence is to steer the future into an end target,” and that looking at BSG as a cautionary tale, it is necessary to remove some of the unpredictability.

One of the other panelists noted that they regarded science fiction as “not so much a prediction of what will happen in the future as a commentary on the present,” to which Mary McDonnell emphatically nodded.

The moderator then asked Dr. Bostrom about his work in “Friendly AI.” He described it is generally working to ensure that the development of AI is for the benefit of humanity, and that he regrets that this pursuit has “very little serious academic effort.”

In a dynamic change of pace, the moderator then wanted to devote some time to Kevin Warwick’s experiments into turning himself into a Cyborg. Video of some of this can be found on YouTube and he’s also written about the experience in his book, I Cyborg. He described a series of experiments, one in which he implanted a chip in his head which was implanted so as to allow him to be linked to a robotic arm on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean and actually feel and experience what this arm was doing, including the amount of pressure used.

He also described a second experience where a set of sensors implanted in his wife’s arm allowed him to experience and feel what she was doing from across the room, which is written up in IEEE Proceedings of Communications as “Thought communication and control: a first step using radiotelegraphy.” The description of this experiment caused a great deal of curiosity for all involved as they tried to understand exactly what he was feeling and how he felt it, and at one point even Mary McDonnell started asking questions with a great deal of amusing innuendo.

His final experiment involved providing his wife with a necklace that changed color depending on whether he was calm or “excited” based on biofeedback it received from a chip in his brain, and again led to a great deal of innuendo.

The moderator drew her portion of the panel to a close by asking the actors what they would take from their experience on BSG. Mary McDonnell said that

I no longer suffer from the illusion that we have a lot of time. On a spiritual and political plane, I’d like to be of better and more efficient service, because it really feels like we’re running out of time.

Michael Hogan said there’s nothing he could say that would improve on Ms. McDonnell’s statement.

There was then only time for two questions from the audience. The first question was whether or not AI should be regulated by the government. Dr. Lipson answered that indeed it should not, and that instead it should be open and transparent. Dr. Warwick added that based on the U.S.’s democratic system, that AI belongs to all people regardless.

The other question from the audience was directed toward Mary McDonnell and was whether or not she was surprised to learn that she wasn’t as Cylon. Ms. McDonnell answered that she felt it very necessary that Laura remain on the “human, fearful plane” and that to do otherwise with her would’ve been a cruel joke. As such, she wasn’t surprised by her continued humanity.

~*PoliSciPoli*~

]]>