ScriptPhD.com’s coverage of the World Science Festival in New York City continues towards the physics and mathematics realm. Day 3 events on Friday included an intimate discussion about astrophysics and the new James Webb Telescope, set to replace Hubble in June of 2014, a panel about hearing and visualizing gravity with Albert Einstein’s modern successors, and a panel about the very limits of our understanding of science—the line between what we do and don’t (or can’t) know—and its bridge to culture and art. Contributions to our coverage were done by New York City science writers Jessica Stuart and Emily Elert. Synopses and pictures of three extraordinary panels with the premier scientists of our time under the “continue reading” cut.

FROM THE CITY TO THE STARS: Star-gazing with the Webb Telescope — June 4, 2004

It was a cloudy night in Manhattan, but the dozens of amateur astronomers and spectators who came down to Battery Park didn’t seem to mind. People from all over the tri-state area brought out their telescopes, ranging from under a foot to over 7 feet long, in hopes of seeing Saturn and with luck, some other planets. Many came early in the day to set up, happy to talk to visitors about their interest in the cosmos. As the sun started to set, Dr. John Mather, Dr. John Grunsfeld, Dr Heidi Hammel, and moderator Miles O’Brien sat down to talk with about the James Webb Space Telescope and space in general. Acknowledging all of the amateur astronomers in the audience, they pointed out that in 1994, you needed the Hubble Telescope to see many of the things that their personal telescopes set up in the park could see on a clear dark night from anywhere.

O’Brien brought out a laser pointer, and Dr. Mather explained in detail all of the parts of the full-scale model of the James Webb Space Telescope that was set up nearby. He explained how, because of its size and the rocket that it will go to space on, it will launch folded up, and then deploy itself in space. Its final destination is a million miles from the earth, at a Lagrange point, where it will be stable. There will be no repair missions to the Webb Telescope, as there have been to the Hubble, which is in orbit 300 miles from earth. Dr. Grunsfeld was on three of the five repair missions to Hubble, and spoke of how amazing it was to see Neptune from that vantage point.

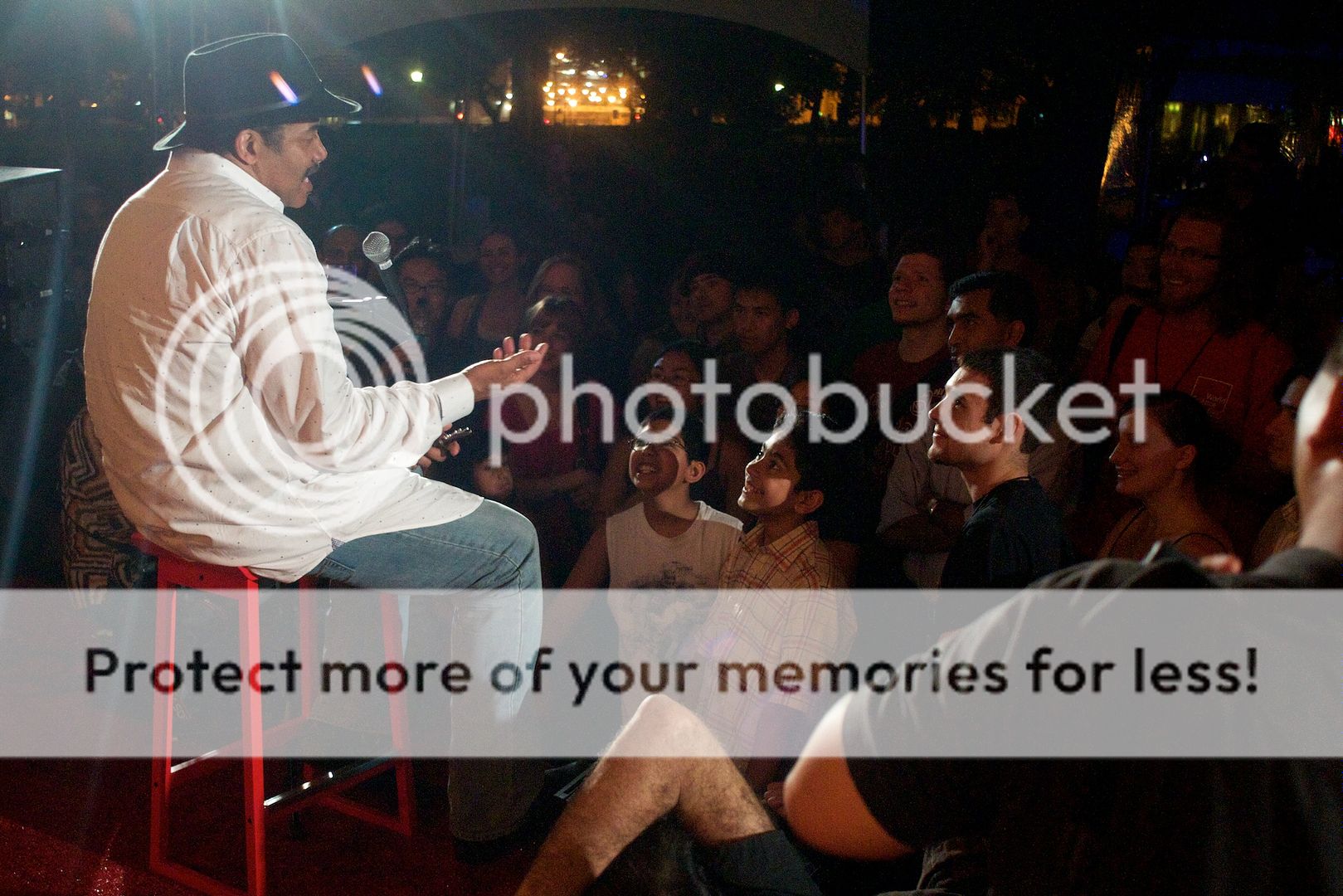

Audience Q&A ranged from life on other planets, the end of space, and how black holes work. The scientists were dynamic and engaging, doing their best to answer all of the questions. Fortunately, cloud cover didn’t matter and telescopes weren’t need to see the star that much of the audience was interested in. At the end of the panel discussion, Astrophysicist, Director of the Hayden Planetarium, and NOVA host Neil deGrasse Tyson took the stage. He was supposed to kick off the star-gazing, but without much to see in the sky, he entertained the audience with more stories and facts about astronomy and science. Kids (and several adults), moved up to sit in the grass in front of the stage, to better hear and see this very animated legend.

Tyson grew up in the Bronx, and as a child, knew the nine stars he could see in the night sky. He admitted that even now, when he’s out of the city and can see a sky full of stars, he thinks “this is just like the Hayden Planetarium,” the first place he learned of the thousands of stars that could be seen with the naked eye. Even though he has the opportunity to use any manner of professional telescope out there, he praised the amateur astronomers for their interest and passion.

After the talk concluded, and the telescope owners and part of the crowd dispersed to try to star-gaze, a child who didn’t get called on approached the stage to ask Tyson his question. This turned into an impromptu sit-down session, with a large crowd gathering around. Tyson enthusiastically obliged, engaging the fans, especially the children who clamored to ask all manner of questions, wondering how black holes work, if there’s mass in space, and where Tyson got his hat. As the crowd grew, a microphone was brought back out, and those who stuck around were treated to an intimate audience with one of the best known astrophysicists in the country.

As the evening grew late, the clouds started to part, and the astronomers tried to find objects in the sky and on the tops of nearby buildings for the visitors to see. Despite the low visibility, everyone left happy, excited to have been a part of a wonderful evening in the park.

The James Webb Space Telescope is on display through Sunday, June 6, at 6pm, at Battery Park. Admission is free.

Jessica Stuart is a writer, photographer and videographer living in New York City. Find her on her personal blog, and Twitter.

ASTRONOMY’S NEW MESSENGERS — June 4, 2010

Marcia Bartusiak, the moderator at Friday night’s World Science Festival event Einstein’s New Messengers, walked on stage to a peculiar soundtrack. It wasn’t music at all, but a sharp thumping sound that started out in slow beats and, over the course of several seconds, progressed to a high-pitch whir like a baseball card in the spokes of bicycle wheel, before going out in an undignified “POP.”

It may not be beautiful, but it’s a sound physicists at the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) are dying to hear—gravitational waves, emanating from colliding, super-massive black holes like ripples spreading out through a pond. “In a way, our universe has been like a silent movie,” said Bartusiak. “Gravitational waves are going to turn us into talkies.”

Gravitational waves aren’t actually sound waves—they are ripples in space-time, oscillations in the very fabric of the cosmos, caused by the movements of massive objects. The waves were predicted by Einstein’s general theory of relativity, but they have never been directly detected. That is, until…

Until soon, physicists hope. Among the most hopeful, to be sure, is Rainer Weiss, a member of Friday’s panel and the inventor of the massive experiment designed to detect them. The experiment, currently operating at five locations on earth, involves splitting a beam of light through the L-shaped, four-kilometer-long arms of an interferometer. If a gravitational wave passes through, one of the beams of light will be stretched while the other is squeezed, resulting in a tiny, eentsy, weensty difference in the amount of time it takes the light to bounce back to the middle.

Why are eight kilometers of laser necessary to detect a wiggle the size of the nucleus of a hydrogen atom? “The smaller the thing we’re trying to detect, the bigger the experiment we need to do it,” joked Kip Thorne, a theoretical physicist on the panel (and one of the world’s best experts on gravity).

On stage, Thorne and Weiss kept up a lively, good-natured banter over the merits of theory versus experimentation, while Andrea Lommen, an observational astronomer, talked about her preferred method of seeking out gravitational waves—by looking for small fluctuations in the energy emitted from pulsars. “Pulsars are my detectors,” she said. “I already have this galactic-scale detector that’s been given to me by the universe.”

Whatever their method, the three scientists are all hoping that the information riding in those elusive waves will allow them to gain insight into the remotest, strangest parts of the universe—from the formation of galaxies to time-creeping depths of black holes.

THE LIMITS OF UNDERSTANDING — June 4, 2010

One of the greatest public misconceptions about science, reinforced by our years of schooling and fat, glossy textbooks full of facts, is that it deals with stuff we already know about our world, when in fact all of science takes place at the boundary between what we know and what we don’t. And no one seems more aware of this than the panelists at Friday’s event The Limits of Our Understanding, at the World Science Festival.

The basis of the panel discussion was the idea of mathematical uncertainty or, more precisely, Godel’s incompleteness theorem, proposed in 1931, which says that it’s impossible to prove or disprove all of the parts of any formal system. “Eighty years later, we still don’t understand what Godel proved,” joked Gregory Chaitin, a mathematician and computer scientist. Then he added, more seriously, “the fallout hasn’t stopped.”

Perhaps, “the fallout” from Godel’s incompleteness theorem isn’t a semi-new phenomenon, but a problem that humans have been grappling with since the beginning of human thought. Mario Livio, an astrophysicist, compared it to Plato’s cave allegory, where the workings of the universe are played out by a fire in a cave, but we can only see the shadows cast on the wall. Are we describing the world as it really is, or only as we perceive it to be, with the fierce limitations of our senses?

And if we had other senses, Livio asked, and a different experience of the world—if, for example, we were jellyfishes living at the bottom of the Pacific Ocean, would we have invented arithmetic and geometry? Or what if our senses were simply altered? “If we saw in infrared, we might not have shapes,” he suggested. “It’s an artifact of our sense perceptions.”

“This is where absolute truth is gone!” cried Chaitin. “It’s gone nowadays—it’s out of fashion. But it’s still important to think about, because it might come back!”

Along with the argument about absolute and relative truth, the panel discussion ranged somewhat freely between each of the panelist’s subjects of interest—Rebecca Goldstein, a philosopher and novelist, brought up the question of consciousness, and suggested that the body of facts relating each of us to the natural world does not, in sum, add up to a complete description of the human experience.

Marvin Minksy, a cognitive scientists, disagreed. “Consciousness is just a bunch of different problems dumped into the same trash basket,” he contended. He pointed out that Galileo used the same word for velocity and momentum in his math, and the problem seemed like a very complicated one until someone came along and separated them into two different variables.

But along with this ardently demystifying view of human experience, and the somewhat depressing notion that the universe as we understand it is a mere matter of the tuning of our senses, Minsky gave us all a pretty good argument for showing up. “A molecule of DNA is stable room temperature for one billion years,” he said, but evolution itself is a random thing.

“Evolution remembers what works, but it doesn’t remember the ones that died.” It’s important for us to keep this in mind, he said, because it’s up to us to remember what works and what doesn’t—it’s up to us to transmit knowledge through time.

“Without culture,” Minsky said, “we don’t survive.”

Emily Elert is a freelance science writer living in New York City. Follow her on Twitter.

Follow the World Science Festival on Facebook and Twitter. All photography ©ScriptPhD.com. Please do not use without permission.

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development.

Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

]]>

Begun in 2008 by Columbia University Physicist Brian Greene, the World Science Festival has burgeoned from an intimate cluster of science panels to a truly integrated mega-event melding culture, science, and the arts. Those lucky enough to make it out to New York City to the over 40 events this year will have a chance to learn about a variety of current science topics, go stargazing with NASA Scientists, discuss Faith and Science, and find out why humans commit violent crimes. Those not lucky enough to be there can browse the full list of events here and watch a live-stream of selected events here. ScriptPhD.com is proud to be at the festival, and will be bringing you coverage through Sunday through the eyes of talented science writers Jessica Stuart and Emily Elert. Our blogging will include event summaries, photographs, interviews and even videos of the street fairs and science literally spilling over into the streets of New York.

OPENING NIGHT GALA — June 2, 2010

The 2010 World Science Festival began tonight with a gala celebration at Avery Fisher Hall in Lincoln Center. The grand venue played host to a number of luminaries, among them Alan Alda, Yo-Yo Ma, Kelli O’Hara, and the star of the evening, legendary physicist Stephen Hawking.

Alda started off the evening. “It seems strange that with how much we know, how much is known about science, so little reaches us, the general public…” He continued, “Science is still obscured by a black hole of misunderstanding, and when light tries to escape, it gets drawn back in.” The World Science Festival’s goal is to “cultivate and sustain a general public informed by the content of science, inspired by its wonder, convinced of its value, and prepared to engage with its implications for the future.” Judging by the line up they have this coming week, they’ll do a great job of that again this year.

The opening gala opening brought out a wide variety of people. From Nobel Prize winners to Broadway stars, the house was packed. Musical numbers all tied into the science theme. Broadway singers Rebecca Luker and Kelli O’Hara charmed the room, with “When the Sea is all around Us” and “Stardust,” respectively. Yo-Yo Ma and the Silk Road Ensemble played a lively Persian-inspired version of the Icarus story.

Undoubtedly, the highlight of the evening was honoree Stephen Hawking.

“Back in 1965, when I first saw the skyscrapers of Manhattan, I had been recently diagnosed with ALS and had a 2 year life expectancy. Therefore, no one is more surprised or delighted than myself to be back here 45 years later…”

Hawking has long been interested in bringing science to the public. Along with countless scientific publications, he’s written several books for the layperson, including his bestseller A Brief History of Time, and the updated A Briefer History of Time. His introduction this evening featured a clip of him from The Simpsons (He’s appeared in several episodes – tonight’s clip was from the Season 16 episode “Don’t Fear the Roofer”).

Those who know Dr. Hawking spoke of his wit and humanity. His sense of humor came through in his brief remarks.

“For my honeymoon in the 60’s, I brought Jane to a physics conference here in New York. It seemed to be both a logical and romantic destination. However, I have since learned that logic and romance do not always go together as well as I once believed. Some things cannot be solved by algebra, I am sorry to say.”

PIONEERS OF SCIENCE — June 3, 2004

Early this morning, just a block away from Times Square, a group of 21 lucky middle and high school students gathered to chat with astrophysicist Dr. James Mather. They were joined via video chat by students from Florida, Kansas, and students from two schools in Ghana who traveled more than 3 hours from their rural towns to participate.

As the students prepared for the chat to begin, they wrote out and practiced the questions they wanted to ask with their friends. One young man approached Dr Mather in awe, “Oh my god, it’s such an honor to meet you!” “It’s an honor to meet you, too,” he replied. Dr. Mather is by all accounts a brilliant scientist. He’s the recipient of a 2006 Nobel Prize in physics, and is the Senior Project Scientist on the James Webb Space Telescope, slated to launch in 2014 (which is currently on exhibit in Bryant Park and which we will be bringing you video coverage of). He’s also a fantastic communicator, easily bridging the gap between high level NASA science and the inquiries of young students. As question after question came his way, he distilled his answers to clearly explain how the universe, and the tools we’ve built to understand it, work.

This group of bright students from around the globe kept him on his toes, asking questions such as “How is it possible to have an infinite amount of space? What contains it?” and “What does COBE do exactly?” They asked about how cosmic microwave background affects society, and how scientists see back in time to look at dust from the big bang. He answered many questions with more questions, and did not shy away from saying he did not know some answers, an important aspect of being a good, inquisitive scientist.

Dr. Mather explained to the students the mysteries of dark matter and dark energy, how we could use the presence of oxygen to detect other life in space, and the challenges they faced when they had to redesign the new telescope after the Challenger explosion, reducing the weight by half and finding a new rocket to send the now foldable telescope up on.

When asked “Did you ever think you’d be an astrophysicist when you were young?” Dr Mather replied “I didn’t even know what one was…” Towards the end, the conversation turned to how students could become scientists themselves. “You find something that interests you, and you follow it…Some people want to solve crossword puzzles all day long, and so they become experts at crossword puzzles… some people become fascinated with science, and they follow some special interest.” Mather continued, “Einstein wanted to know about compass needles. I wanted to know about stars… You just have to follow what interests you, and pretty soon you are led to, ‘I really want to know more math, because math is part of science’, and then ‘I need to know other parts of science that relate to my part of science’, and so, you just follow what you want to do, and try to get people to help you, and I see that everybody here already has had some help, because you got here. My impression is that there’s a lot of help available for people who want it, and if you say ‘I want to study science,’ somebody will say ‘I want to help you study science.’ So perhaps that’s the most important thing to know, that people want to help you if you want to do this.” He finished by telling the students to look him up and feel free to email him with more questions.

As the talk concluded, the remote locations signed off, and the students in New York swarmed the front of the room, buzzing with excitement and basking in the attention of this true Pioneer of Science.

OUR GENOMES, OURSELVES — June 3, 2010

Few medical issues are fraught with as much controversy as genomic testing. Will it lead to designer babies? Could knowing what’s in your DNA hurt your chances of getting insurance or a job? What would you do if you found out you had BRCA1, the “breast cancer” gene?

Our Genome Ourselves (https://www.worldsciencefestival.com/our-genomes-ourselves) tackled all of these questions and more.

Panelists included Francis Collins (Geneticist, Physician, & Director of the NIH), George Church (Molecular geneticist), and Robert C. Green (Neurologist & Epidemiologist), with moderator Richard Besser (ABC News Senior Health and Medical Editor, former acting director of CDC and Physician). All experts in the field of genomics, these four men offered both broad medical and policy knowledge, and a truly compelling panel presentation.

The biggest takeaway, repeated by all of the panelists, is that very very few genes are deterministic – that is, there are not many conditions that can be indicated or eliminated by the presence or absence of one single gene mutation. Each person has some 6 billion genes in each cell. The vast majority of traits and predispositions are caused by a combination of factors, many of which are not fully understood. We are still in the very early stages of being able to interpret what a sequenced genome might indicate – even if you were fully sequenced tomorrow, it would be very prudent to revisit the interpretation next week and next month and next year. The sequence of letters should stay the same (barring any typographical errors), but what they might indicate for your future could be drastically different, based on new information being found daily.

Many people think that if they find out what their DNA says, they’ll have a road map for the diseases they’ll get and the life they’ll live, but in almost every case, that couldn’t be further from the truth. Without taking into account environment and other factors, we have a huge over-expectation of what genomics can tell us. There are other issues, too, beyond interpretation. Many emotional, ethical, and educational factors come into play. What about testing our children? At what point do they have the right to know they’re likely to get Parkinsons? Dr. Green wondered if it’s wise to give people results that say they have a 40% greater chance of a disease? What if that actually means their overall odds go from 1% to under 2%? A very important side question – do people understand statistics well enough to truly understand what risks indicated by genetic markers are saying?

Dr. Collins pointed out that typically, when considering what we want to know about our own personal genomic sequence, we consider three things:

1. What kind of risk is it able to provide you with?

2. What’s the burden of the disease?

3. Is there an intervention?

The panelists agreed that as genetic testing becomes more prevalent, we need to provide proper training to medical professionals, whether that be physicians, physicians assistants, nurse practitioners, or others, to properly explain the meaning of the results to patients. We also need to improve and implement a solid electronic medical record system, so that the results can be applied. Minorities and other under-served populations need to be recruited to donate their DNA, which likely means dealing with the practicality of being able to promise privacy to those who are more skeptical than the original volunteers of interested researchers.

Some of the bigger questions can be easily answered. For now, the idea of being able to go to a geneticist and selecting a tall, blue-eyed, muscular son, with musical abilities, athletic prowess, and above average intelligence, is out of the picture. Too many factors go into each one of those traits for it to be easily selectable – it’s currently impossible to optimize an embryo for those types of genes. The Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act of 2008 provides a legal framework so that Americans cannot be discriminated against based on genetic information, as it pertains to health care and employment. As for what individuals will decide to do if they’re shown to have BRCA1, that will remain a personal decision.

The first draft of the human genome sequence was completed on June 26, 2000. Twenty years later, we’ve come so far, yet still know so little. It will be fascinating to see what science achieves in another couple of decades.

Follow the World Science Festival on Facebook and Twitter. All photography ©ScriptPhD.com. Please do not use without permission.

Jessica Stuart is a writer, photographer and videographer living in New York City. Find her on her personal blog, and Twitter.

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development.

Follow us on Twitter and our Facebook fan page. Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

]]>