“First of all, let me assert my firm belief that the only thing we have to fear is fear itself—nameless, unreasoning, unjustified terror which paralyzes needed efforts to convert retreat into advance.” These inspiring words, borrowed from scribes Henry David Thoreau and Michel de Montaigne, were spoken by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt at his first inauguration during the only era more perilous than the one we currently face. But FDR had it easy. All he had to face was 25% unemployment and 2 million homeless Americans. We have, among other things, climate change, carcinogens, leaky breast implants, the obesity epidemic, the West Nile virus, SARS, avian/swine flu, flesh-eating disease, pedophiles, predators, herpes, satanic cults, mad cow disease, crack cocaine, and let’s not forget that paragon of Malthusian-like fatalism—terror. In his brilliant book The Science of Fear, journalist Daniel Gardner delves into the psychology and physiology of fear and the incendiary factors that drive it, including media, advertising, government, business and our own evolutionary mold. For our final blog post of 2009, ScriptPhD.com extends the science into a personal reflection, a discussion of why, despite there never having been a better time to be alive, we are more afraid than ever, and how we can turn a more rational leaf in the year 2010.

Prehistoric Predispositions and the Human Brain

Let’s talk about psychology for a moment. The psychology of fear, to be specific. Our minds largely evolved to cope with the “Environment of Evolutionary Adaptation”; Stone Age survival needs hard-wired into our brains to create a two-tiered system of conscious and subconscious thought. Elucidated by 2002 Nobel Prize winner in economics Daniel Kahneman, the systems are divided into the prehistoric System One (Gut) and System Two (Head). Gut is quick, evolutionary and designed to react to mortal threats, while Head is more modern, conscious thought capable of analyzing statistics and being rational. In a seminal 1974 paper published in the journal Science, Kahneman and his research partner Amos Tversky punctured the long-held belief that decision-making occurs via a Homo economicus (rational man) by proving that decisions are mostly made by the gut using three simple heuristics, or rules. The anchoring and adjustment heuristic (Anchoring Rule) involves grabbing hold of the nearest or most recent number when uncertain about a correct answer. This helps explain why the number 50,000 has been used to describe everything from how many predators are on the Internet in the 2000s to how many children were kidnapped by strangers every day in the 80s to the number of murders committed by Satanic cults in the 90s. The representativeness heuristic, or Rule of Typical Things, is our Gut judging things based on largely learned intuition. This explains why many predictions by experts are often as wrong as they are right. And why, despite being convinced they are not racist, Western societies perpetuate a dangerous stereotype of the non-white male. Finally, and most importantly, the availability heuristic, or Example rule, dictates that the easier it is to recall examples of something, the more common it must be. This is particularly sensitive to our memory formation and retention, particularly of violent or painful events, which were key to species survival in dangerous prehistoric times.

University of Oregon psychologist Paul Slovic added to these the affect heuristic, or Good/Bad Rule. When faced with something unfamiliar, Gut instantly decides how likely it is to kill it based on whether it feels good or should be good. This explains why we irrationally fear nuclear power, which have intellectually been shown to not be nearly as dangerous as we think they are, while we have no qualms about suntanning on a beach, which feels good, or getting an X-ray at the doctor’s office despite both having been shown to be more dangerous than estimated. Psychologists Marty Frank and Thomas Gilovich showed that in all but one season from 1970 to 1986, the five teams in the NFL and three teams in the NHL that wore black uniforms (black = bad) got more penalty yards and penalty minutes than league-average, respectively, even when wearing their alternate uniforms. Finally, scientist Peter Watson discovered that people judge risk not based on scientific information, but rather herd mentality and conformity, termed confirmation bias. Once having formed a view, we cling to information that supports that view while rejecting or ignoring information that casts any doubt on it. This can be seen in internet blogs of like-minded individuals that act as echo chambers and media and organization perpetuating a fear as rumor until it is accepted by the group as a mortal danger, despite no rational evidence to the contrary.

It’s a downright shame that this hallowed body of research took scientists such a long time to amass and ascertain, because they could have easily found it in the skyscrapers of Madison Avenue, where the psychology of fear has not only been long-defined, but long-exploited by advertising agencies and media moguls to sell products, news, and…more fear.

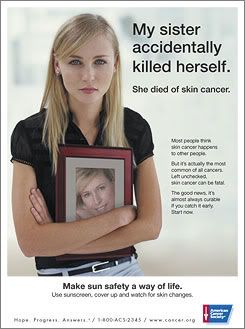

At its heart, effective advertising has always been about forming an emotional bond with consumers on an individual level. People are more likely to engage with a brand or buy a product if they can feel a deep connection or personal stake. This can be achieved through targeted storytelling, creativity, and the tapping and marketing of subconscious fear, coined as “schockvertising” by ad agencies. “X is a frightening threat to your safety or health, but use our product to make it go away.” It’s a surprisingly effective strategy and has been applied of late to disease (terrific read on pharmaceutical advertising tactics), the organic/natural movement, and politics. Purell (which The ScriptPhD will disclose being a huge fan of) was originally created by Pfizer for in-hospital use by medical professionals. In 1997, it was introduced to market with an ad blitz that included the slogan “Imagine a Touchable World.” I just did; it’s called the world up until 1997. Erectile dysfunction, hair loss, osteoporosis, restless leg syndrome, shyness, and even toenail fungus are now serious ailments that you need to ask your doctor about today. This camouflaged marketing extends to health lobby groups, professional associations, and even awareness campaigns. Roundly excoriated by medical professionals, a 2007 ad campaign pictured on the right warned of the looming dangers of skin cancer. Though the logo on the poster is that of the American Cancer Society, it’s sponsored by Neutrogena—a leading manufacturer of sunscreen.

“For the first time in the history of the world, every human being is now subjected to contact with dangerous chemicals, from the moment of conception until death,” wrote marine biologist Rachel Carson in her 1962 environmental bombshell Silent Spring. Up until then, ‘chemical’ was not a dirty word. In fact it was associated with progress, modernity, and prosperity, as evidenced by DuPont Corporation’s 1935 slogan “Better things for better living…through chemistry” (the latter part being dropped in 1982). Carson’s book preyed on what has become the biggest fear in the last half-century: cancer. It famously predicted that one in every four people would be stricken with the disease over the course of their lifetimes. These fears have been capitalized on by the health, nutrition and wellness industry to peddle organic, natural foods and supplements that veer far away from laboratories and manufactured synthesis. While there is nothing wrong with digging into a delicious meal of organic produce or popping a ginseng pill, the naturally occurring chemicals in the food supply exceed one million, none of which are liable to the rigorous safety guidelines and regulations that are performed on perscription drugs, pesticides and non-organic foods. In fact, the lifetime cancer risk figures invoked by everyone from Greenpeace to Whole Foods is not nearly as scary when adjusted for age and lifestyle. “Exposure to pollutants in occupational, community, and other settings is thought to account for a relatively small percentage of cancer deaths,” according to the American Cancer Society in Cancer Facts and Figures 2006. It’s lifestyle—smoking, drinking, diet, obesity and exercise—that accounts for 65% of all cancers, but it’s not nearly as sexy to stop smoking as it is to buy that imported Nepalese pear hand-picked by a Himalayan sherpa. Of course, this hasn’t prevented the organic market from growing 20% each year since the early 90s, with a 20-year marketing plan. The last frontier of fear advertising is politics. Anyone who has seen a grainy, black and white negative ad may be cognizant they are being manipulated, but may not know exactly how. Coined the “get ‘em sick, get ‘em well” model in the 1980s, political scientist Ted Brader notes in Campaigning for Hearts and Minds that 72 percent of such ads dominate an appeal to emotions versus logic, with nearly half appealing to anger, fear or pride. Take a look at the gem that started them all, a controversial, game-changing 1964 commercial called “Daisy Girl”. Emotional, visceral, and only aired once, this ad was widely credited with helping Lyndon B. Johnson defeat Barry Goldwater in the Presidential election:

And finally, we have the media. That venerated congregation of communicators dedicated to broadcasting all that’s newsworthy with integrity. Perhaps in an alternate universe. Psychologists specializing in fear perception have concluded that media disproportionately covers dramatic, violent, catastrophic causes of death. So after watching a Law and Order or CSI marathon, a Dateline special about online predators, and a CNN special on the missing blonde white woman du jour, you tune in to your local news (“Find out how your windshield wipers could kill you, tonight at 11!”). While the simplest explanation is that media profits from fear, it is also tailor made to two of the rules discussed above: the Example Rule and the Good/Bad rule. We don’t recognize that a disease covered on House or a news special about a kidnapping or violent suburban murder spree are rare, only that they are Bad and the last thing we saw, so they head straight to our Gut. The overwhelming preoccupation of the modern media is crime and terrorism, with a heavy focus on individual acts bereft of broader context. Just as they are in advertising, emotions and individual connection are essential in media crime reporting. The evolutionary desire to punish someone for wrongdoing towards someone else is hard-wired into our brains, and easier to conjure when watching an isolated story about someone relatable (a daughter, a mother, a little old lady) than about scores of dead or suffering millions of miles away, no matter how tragic. A convincing body of psychology research has concluded that individuals who watch a large amount of television are more likely to feel a greater threat from crime, believe crime is more prevalent than statistics indicate, and take more precautions against crime. Furthermore, crime portrayed on television is significantly more violent, random, and dangerous than crime in the “real” world. While this blog diverges with Gardner’s offhanded minimalization of the very real threat posed by radical terrorist organizations, he does bring forth a valid argument of reality versus risk perception. Excluding the State of Israel, a lifetime risk of injury or death in a terror attack is between 1 in 10,000 and 1 in a million. Your risk of being killed by a venomous plant or animal? 1 in 39,873. Drowning in a bathtub? 1 in 11,289. Being killed in a car crash? 1 in 84. Think about the last time CNN devoted a Wolf Blitzer special to venomous plants, bathtubs, or car crashes. Furthermore, the total cost of counterterror spending in the US between 2001 and 2007 was $58.3 billion, not including the $500 billion – $2 trillion price tag on the Iraq war. And the extra-half hour delay at the airport for security, the effectiveness of which we have witnessed this very week, costs the US economy $15 billion per year. A panel of experts gathered a month ago

at the Paley Media Center in New York City to discuss the future of news media, audience preferences, and content in a competing marketplace. The conclusion? More sex, more scandal. In other words, more of the same.

It is highly unusual, if rare, for me to break the fourth wall as Editor of ScriptPhD.com to get personal and let readers in as Jovana Grbi?. But, in the spirit of New Year’s resolutions, holiday warmth, and a little too much champagne, what the heck… lean in closely, because I’ll only say this once for posterity. I am more often afraid than unafraid. I am not an outlying exception to the principles listed above, but rather an adherent to their very human origins. From as far back as I can remember, I have wanted to be a professional writer. I was very good at math and science, but creative doodling, daydreaming, and filling my head and notebooks with words was what I lived for. Dramatic, artsy types were who I hung out with, admired, even lived with in college. So why not study film or creative writing? And, in the middle of graduate school, when it dawned on me that I loved science but didn’t live it, why not change course and pursue my dreams right away? Because I chose to follow the tenable rewards of the logical and attainable rather than risk the abstract (gut beat out head). Quite simply, I was afraid. I began 2009 by standing on the Mall in Washington, DC with a million or so of my closest friends to witness our nation’s first African-American President take the oath of office. 2009 was also the year that I broke free to launch this blog, its accompanying creative consulting practice, and my career as a writer. Neither accomplishment, one so public and one so personal, could have transpired through fear. Naturally, since we move and think as a herd, I had a lot of help from my friends. But the bitter irony is that cracking my fears has left me more scared than ever. There are still a million things that could go wrong, a million burdens and responsibilities that I now shoulder alone, and let’s not romanticize the creative lifestyle, the ultimate high-risk, low-reward proposition. But you know what, dear readers? I’ve never been happier! So, as we head into this, the last year of the first decade of our new millennium, we must individually and collectively ask ourselves, “What do I fear?” What great glucocordicoid blockade, personal or professional, prevents you from existential liberation?

Especially amidst vulnerable times like these, a retrospective insight into the rational reveals the psychological trail of breadcrumbs that cracked the mirage we’ve been living under this past decade. We would see that Jim Cramer, a so-called expert in the capricious art of the stock market (the fluctuations of which have been linked by psychologists to weather patterns) was simply evoking the anchoring and heuristics numbers rule as he confidently reassured his viewers to invest in Bear Stearns. The company went under a week later. We would see that scores of bankers, investors, insurance giants, and people just like you and me were lulled by the example rule to falsely believe the housing bubble would never burst because, hey, a week ago, everything was fine. And we can still see the media (print, social, digital, and everything in-between) trying to painfully bend the rule of typical things into a pretzel to forecast when and how this current recession will end, with optimistic economists predicting a 2010 recovery and more austere types warning that high unemployment might take a full decade to assuage. Caught in this miasmic cloud is a primed public receptive to the advertising, entertainment and news messages aimed straight at our primordial gut instincts to perpetuate a culture of fear. To step out of the cloud is to shed the hypothetical for the actual. While recessions are frightening and uncertain, they are also a natural part of the economic cycle, and have given birth to the upper echelon of the Fortune 500 and even the iPod you’re listening to as you read this blog. Rather than focusing on the myriad of byzantine ways we could die, we might devote energy and economy to putting a dent in our true terrorists: heart and cardiovascular diseases, cancer and diabetes. Rather than worrying about whether we’re eating the perfect, macrobiotic, garden-grown heirloom tomato, we should all just eat more tomatoes. Instead of acquiescing to appeals of vanity from pharmaceutical companies, we should worry about feeding the hungry and rebuilding inner-city neighborhoods. And every once in a while, we should let our gut worry about digesting dinner, and let our head worry about risk-assessment. We might stop worrying so much. I will conclude 2009 by echoing President Roosevelt’s preamble to not fearing fear: “This great Nation will endure as it has endured, will revive and will prosper.” I personally extend his wishes to every single one of you around the world. Just make sure to look both ways before crossing the street. There’s a 1 in 626 chance you could die.

Happy New Year.

~*ScriptPhD*~

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and pop culture. Follow us on Twitter and our Facebook fan page. Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

6 thoughts on “From the Annals of Psychology: Fear and Loathing in a Modern Age”