Earlier this year, the Susan G. Komen Foundation made headlines around the world after their politically-charged decision to cut funding for breast cancer screening at Planned Parenthood caused outrage and negatively impacted donations. Despite reversing the decision and apologizing, many people in the health care and fund raising community feel that the aftermath of the controversy still dogs the foundation. Indeed, Advertising Age literally referred to it as a PR crisis. If all of this sounds more like spin for a brand rather than a charity working towards the cure of a devastating illness, it’s not far from the truth. Susan G. Komen For the Cure, Avon Walk For Breast Cancer and the Revlon Run/Walk For Women represent a triumvirate hegemony in the “pink ribbon” fundraising domain. Over time, their initial breast cancer awareness movement (and everything the pink ribbon stood for symbolically) has moved from activism to pure consumerism. The new documentary Pink Ribbons, Inc. deftly and devastatingly examines the rise of corporate culture in breast cancer fundraising. Who is really profiting from these pink ribbon campaigns, brands or people with the disease? How has the positional messaging of these “pink ribbon” events impacted the women who are actually facing the illness? And finally, has motivation for profit driven the very same companies whose products cause cancer to benefit from the disease? ScriptPhD.com’s Selling Science Smartly advertising series continues with a review of Pink Ribbons, Inc..

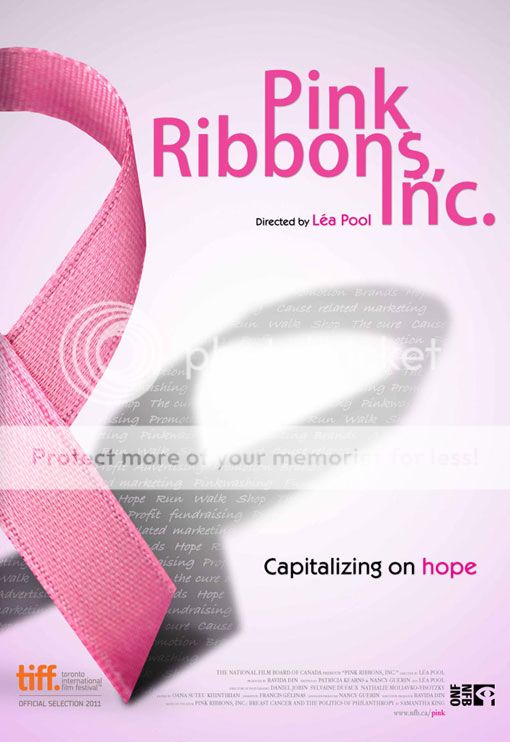

“We used to march in the streets. Now you’re supposed to run for a cure, or walk for a cure, or jump for a cure, or whatever it is,” states Barbara Ehrenreich, breast cancer survivor and author of Welcome to Cancerland, in the opening minutes of the documentary Pink Ribbons, Inc. Directed by Canadian filmmaker Lea Pool and based on the book Pink Ribbons, Inc.: Breast Cancer and the Politics of Philosophy by Samantha King, the documentary features in-depth interviews with leading authors, experts, activists and medical professionals. It also includes an important look at the leading players in breast cancer fundraising and marketing. The production crew filmed a number of prominent fundraising events across North America, using the upbeat festivities (where some didn’t even visibly show the word ‘cancer’) as the backdrop for exploring the “pinkwashing” of breast cancer through marketing, advertising and slick gimmicks. At the same time, showcasing well-meaning, enthusiastic walkers, runners and fundraisers is a double-edged sword and was handled with the appropriate sensitivity by the filmmakers. Pool wanted to “make sure we showed the difference between the participants, and their courage and will to do something positive, and the businesses that use these events to promote their products to make money.”

Often lost amidst the pomp and circumstance of these bright pink feel-good galas is that the origins of the pink ribbon are quite inauspicious. The original pink ribbon wasn’t even pink. It was a salmon-colored cloth ribbon made by breast cancer activist Charlotte Haley as part of a grass roots organization she called Peach Corps. From a kitchen counter mail-in operation, Haley’s vision grew to hundreds of thousands of supporters, so much so that it caught the attention of Estee Lauder founder Evelyn Lauder. The company wanted to buy the peach ribbon from Haley, who refused, so they simply rebranded breast cancer to a comforting, reassuring, non-threatening color: bright pink. And before our very eyes, a stroke of marketing genius was born.

As the pink ribbon movement took hold of the fundraising community, the money started to spill over into mainstream advertising, adorning everything from the food we eat to the clothes we wear, all under the auspices of philanthropy. In theory, people should feel great about buying products that return some of their profits for such a great cause. In practice, many of these campaigns simply throw a bright pink cloak over false, if not cynical, advertising. Take Yoplait’s yearly “Save Lids to Save Lives” campaign:

For every lid you save from a Yoplait yogurt (and mail in, using a $0.44 stamp, mind you!), they will donate 10 cents to breast cancer research. If you ate three yogurts per day for fourth months, you will have raised a grand total of $36 for breast cancer research, but spent more on stamps and in environmental shipping waste. Not as impressive when you break it down, eh?

A recent American Express campaign called “Every Dollar Counts” pledged that every purchase during a four month period would incur a one cent donation to breast cancer research. Unfortunately, they never quantified donations commensurate to spending, so that meant whether you charged a pack of gum or a big screen TV to your AmEx, they would donate a penny. The breast cancer community was so outraged by this hubris, they staged a successful campaign to rescind the ads. The fact is, the above examples demonstrate that pink ribbons have become an industry, with demographics and talking points, just like everything else. Pinkwashing campaigns tend to target middle class, ultra-feminine white women. Why? Because they are typical targets that move the products these industries are trying to sell. Take the NFL’s recent pink screening campaign. Well-meaning or not, it came amidst a series of crimes and violence by NFL players, some of which was domestic in nature. One can imagine that players adorned in hot pink gear would have been a smart way to mollify its rather impressive female fanbase.

As Ehrenreich states in the documentary, the collective effect of this marketing has been to soften breast cancer into a pretty, pink and feminine disease. Nothing too scary, nothing too controversial. Just enough to keep raising money that goes… somewhere. Take a look at the recent chipper television campaign for the Breast Cancer Centre of Australia:

While some of the breast cancer-related branding and pink sponsorships mislead through good intentions, others are a dangerous bold-faced lie. Some of the very companies that sponsor fundraising events and make money off of pink revenue either make deleterious products linked to cancer or stand to profit from treatment of it. Revlon, sponsors of the Run/Walk for Women, are manufacturers of many cosmetics (searchable on the database Skin Deep) that are linked to cancer. The average woman puts on 12 cosmetics products per day, yet only 20% of all cosmetics have undergone FDA examination and safety testing. The pharmaceutical giant Astra Zeneca can’t seem to decide if it’s for or against cancer. They produce the anti-estrogen breast cancer drug Tamoxifen, yet also manufacture the pesticide atrazine (under the Swiss-based company Syngenta), which has been linked to cancer as an estrogen-boosting compound. Breast cancer history month (October) is nothing more than a PR stunt that was invented by a marketing expert at… drumroll please… Astra Zeneca! Their goal was to promote mammography as a powerful weapon in the war against breast cancer. But as the American arm of the largest chemical company in the world, the reality is that Astra Zeneca was and is benefiting from the very illness it was urging women to get screened for. Perhaps the most audacious example of them all is pharmaceutical giant Eli Lilly. Sponsors of cancer research and treatment, both in medicine and the community, Lilly produced the cancer and infertility causing DES (diethylstilbestrol), and currently manufactures rBGH, an artificial hormone given to cows to make them produce more milk. rBGH has been linked to breast cancer and a host of other health problems. These strong corporate links in many ways explain the uplifting, happy, sterile messaging behind the pink ribbon. Corporations are, quite bluntly, making money off of marketing cancer, so if they don’t put a smiley face on the disease, they will alienate their customers and the conglomerate businesses pouring money into these campaigns.

Juxtaposed with the uplifting, bombastic, bright pink backdrop of the various cancer fundraisers and rallies, Pink Ribbons, Inc. quietly profiles the IV League, an Austin, TX-based support group for metastatic breast cancer. The women meet on a regular basis to share stories, help each other cope and accept the rigors of the disease and realities of dying. Many of the group members interviewed found current breast cancer campaign marketing offensive, tastelessly positive and falsely empowering (“If you just get screened and get mammograms and eat healthy, breast cancer can’t happen to you!”). The group, which has lost 10 members last year alone, is among a large faction of cancer sufferers that feel left out in the pinkwashing tide of marketing campaigns. Highlighting that sometimes you do get cancer because of no explanation, and sometimes you won’t respond to any treatment is a downer. It’s not the kind of uplifting story that advertising campaigns are built around, leaving the women feeling as if they’re living alone with the fact that they are dying. “You’re the angel of death,” remarks IV Leaguer Jeanne Collins. “You’re the elephant in the room. And they’re learning to live and you’re learning to die.” By utilizing powerful messaging keywords like BATTLE, WAR and SURVIVOR, cancer foundations and brands are subliminally putting down those who didn’t survive. And there are many who don’t survive — someone dies of breast cancer every 69 seconds. Are they suggesting that people who died or didn’t respond to treatment simply didn’t try hard enough? One of the most poignant moments in the film was an IV League Stage 4 cancer patient, probably weeks or months from her death: “You can die in a perfectly healed state.”

Although Pink Ribbons, Inc. is a sobering polemic against the mindless trivialization of commercializing breast cancer and even misdirecting funds from where they can be most helpful, it is not a hopeless film. Far from projecting pessimism, the film showcases the tremendous willpower and manpower that these three-day walks engender. It is simply misdirected. If hundreds of thousands of women and men can be motivated to fundraise, walk, run and (in some cases) jump out of planes, the effort is absolutely there to stop breast cancer. “Do something besides worry to make a difference,” concludes Barbara Brenner. “We have enormous power, if only we’d use it.” Director Lea Pool hopes that the film will encourage people to “be more critical about our actions and stop thinking that by buying pink toilet paper we’re doing what needs to be done. I don’t want to say that we absolutely shouldn’t be raising money. We are just saying ‘Think before you pink.'”

Watch the trailer for Pink Ribbons, Inc. here:

Pink Ribbons, Inc. goes into wide release in theaters nationwide June 8, 2012 and was released on DVD in September of 2012.

~*ScriptPhD*~

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development.

Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

2 thoughts on “Selling Science Smartly: ‘Pink Ribbons, Inc.’ and Breast Cancer as a Profit Industry”