Ray Bradbury, one of the most influential and prolific science fiction writers of all time, has had a lasting impact on a broad array of entertainment culture. In his canon of books, Bradbury often emphasized exploring human psychology to create tension in his stories, which left the more fantastical elements lurking just below the surface. Many of his works have been adapted for movies, comic books, television, and the stage, and the themes he explores continue to resonate with audiences today. The notable 1966 classic film Fahrenheit 451 perfectly captured the definition of a futuristic dystopia, for example, while the eponymous television series he penned, The Ray Bradbury Theatre, is an anthology of science fiction stories and teleplays whose themes greatly represented Bradbury’s signature style. ScriptPhD.com was privileged to cover one of Ray Bradbury’s last appearances at San Diego Comic-Con, just prior to his death, where he discussed everything from his disdain for the Internet to his prescient premonitions of many technological advances to his steadfast support for the necessity of space exploration. In the special guest post below, we explore how the latest Bradbury adapataion, the new television show The Whispers, continues his enduring legacy of psychological and sci-fi suspense.

Premiering to largely positive reviews, ABC’s new show The Whispers is based on Bradbury’s short story “Zero Hour” from his book The Illustrated Man. Both stories are about children finding a new imaginary friend, Drill, who wants to play a game called “Invasion” with them. The adults in their lives are dismissive of their behavior until the children start acting strangely and sinister events start to take place. Bradbury’s story is a relatively short read with just a few characters that ends on a chilling note, while The Whispers seeks to extend the plot over the course of at least one season, and to that end it features an expanded cast including journalists, policemen, and government agents.

The targeting of young, impressionable minds by malevolent forces is deeply disturbing, and it seems entirely plausible that parents would write off odd behavior or the presence of imaginary friends as a simple part of growing up. In both the story and the show, the adults do not realize that they are dealing with a very real and tangible threat until it’s too late. The dread escalates when the adults realize that children who don’t know each other are all talking to the same person. The fear of the unknown, merely hinted at in Bradbury’s story, will seem to be exploited to great effect during the show’s run.

When “Zero Hour” was written in 1951, America was in the midst of McCarthyism and the Red Scare, and the fear of Communism and homosexuality ran rampant. As the tensions of the Cold War grew, so too did the anxiety that Communists had infiltrated American society, with many of the most aggressively targeted individuals for “un-American” activities belonging to the Hollywood filmmaking and writing communities. Bradbury’s story shares with many other fictions of the time period a healthy dose of paranoia and fear around possession and mind control. Indeed, Fahrenheit 451, a parable about a futuristic world in which books are banned, is also a parable about the dangers of censorship and political hysteria.

The makers of The Whispers recognize that these concerns still permeate our collective consciousness, and have updated the story with modern subject matter, expanding the subject of our apprehension to state surveillance and abuse of authority. To wit, many recent films and shows have explored similar themes amidst the psychological ramifications of highly developed artificial intelligence and its ability to control and even harm humans. Our concurrent obsession with and fear of technology run amok is another topic explored by Ray Bradbury in many of his later works. The idea that those around us are participating in a grand scheme that will bring us harm still sows seeds of discontent and mistrust in our minds. For that reason, the concept continues to be used in suspense television and cinema to this day.

One of the reasons Bradbury’s work continues to serve as the inspiration for so much contemporary entertainment is his use of everyday situations and human oddities to create intrigue. One such example is a 5-issue series called Shadow Show based on Bradbury’s work, released in 2014 by comic book publisher IDW. Some of the best artists, writers and comics had agreed to participate in this project since Bradbury had such a huge influence in their writing and art. In this anthology, Harlan Ellison’s “Weariness” perfectly elicits Bradbury’s dystopia in which our main characters experience the universe’s end. The terrifying end of life as we know it is one of Bradbury’s recurring themes, depicted in writings like The Martian Chronicles. He rarely felt the need to set his stories in faraway galaxies or adorn them with futuristic gadgets. Most of his writing focussed on the frightening aspects of humans in quotidien surroundings, such as in the 2002 novel, Let’s All Kill Constance. Much of The Whispers takes place in an ordinary suburban neighborhood, and like many of his stories, what seems at first to be a simple curiosity, is hiding something much more complex and frightening.

Fiction that brings out the spookiness inherent in so many facets of human nature creates a stronger and more enduring bond with its audience, since we can easily deposit ourselves into the characters’ situations, and all of a sudden we find that we’re directly experiencing their plight on an emotional level. That’s always been, as Bradbury well knew, the key to great suspense.

Maria Ramos is a tech and sci-fi writer interested in comic books, cycling, and horror films. Her hobbies include cooking, doodling, and finding local shops around the city. She currently lives in Chicago with her two pet turtles, Franklin and Roy. You can follow her on Twitter @MariaRamos1889.

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development. Follow us on Twitter and Facebook. Subscribe to our podcast on SoundCloud or iTunes.

Each of the brain’s 100 billion neurons has somewhere in the realm of 7,000 connections to other neurons, creating a tangled roadmap of about 700 trillion possible turns. But thinking of the brain as roads makes it sound very fixed—you know, pavement, and rebar, and steel girders and all. But the opposite is true: at work in our brains are never-sleeping teams of Fraggles and Doozers who rip apart the roads, build new ones, and are constantly at work retooling the brain’s intersections. This study of Fraggles and Doozers is the booming field of neuroplasticity: how the basic architecture of the brain changes over time. Scientist, neuro math geek, Science Channel personality and accomplished author Garth Sundem writes for ScriptPhD.com about the phenomenon of brain training and memory.

Certainly the brain is plastic—the gray matter you wake up with is not the stuff you take to sleep at night. But what changes the brain? How do the Fraggles know what to rip apart and how do the Doozers know what to build? Part of the answer lies in a simple idea: neurons that fire together, wire together. This is an integral part of the process we call learning. When you have a thought or perform a task, a car leaves point A in your brain and travels to point B. The first time you do something, the route from point A to B might be circuitous and the car might take wrong turns, but the more the car travels this same route, the more efficient the pathway becomes. Your brain learns to more efficiently pass this information through its neural net.

A simple example of this “firing together is wiring together” is seen in the infant hippocampus. The hippocampus packages memories for storage deeper in the brain: an experience goes in and a bundle comes out. I think of it like the pegboard at the Seattle Science Center: you drop a bouncy ball in the top and it ricochets down through the matrix of pegs until exiting a slot at the bottom. In the hippocampus, it’s a defined path: you drop an experience in slot number 5,678,284 and

it comes out exit number 1,274,986. How does the hippocampus possibly know which entrance leads to which exit? It wires itself by trial and error (oversimplification alert…but you get the point). Infants constantly fire test balls through the matrix and ones that reach a worthwhile endpoint reinforce worthwhile pathways. These neurons fire together, wire together, and eventually the hippocampus becomes efficient. It’s just that easy. (And because it’s so easy, researchers aren’t far away from creating an artificial hippocampus.)

Now let’s think about Sudoku. The first time you discover which missing numbers go in which empty boxes, you do so inefficiently. But over time, you get better at it. You learn tricks. You start to see patterns. You develop a workflow. And practice creates efficiency in your brain as neurons create the connections necessary for the quick processing of Sudoku. This is true of any puzzle: your plastic brain changes its basic architecture to allow you to complete subsequent puzzles more efficiently. Okay, that’s great and all, but studies are finding that the vast majority of brain-training attempts don’t generalize to overall intelligence. In other words, by doing Sudoku, you only get better at Sudoku. This might gain you street cred in certain circles, but it doesn’t necessarily make you smarter. Unfortunately, the same is true of puzzle regiments: you get better at the puzzles, but you don’t necessarily get smarter in a general way.

That said, one type of puzzle offers some hope: the crossword. In fact, researchers at Wake Forest University suggest that crossword puzzles strengthen the brain (even in later years) the same way that lifting weights can increase muscle strength. Still, it remains true that doing the crossword only reinforces the mechanism needed to do the crossword. But the crossword uses a very specific mechanism: it forces you to pull a range of facts from deep within your brain into your working memory. This is a nice thing to get better at. Think about it: there are few tasks that don’t require some sort of recall, be it of facts or experiences. And so training a nimble working memory through crosswords seems a more promising regiment than other single type of brain training exercise.

This is borne out by research. A Columbia University study published in 2008 found that training working memory increased overall fluid intelligence. So the answer to this article’s title question is yes, brain training is very real. (Only, there’s lot of schlock out there.) But hidden in this article lies the new key that many researchers hope will point the way to brain training of the future. Any ONE brain training regiment only makes you better at the one thing being trained. But NEW EXPERIENCES in general, promise a varied and continual rewiring of the brain for a fluid and ever-changing development of intelligence. In other words, if you stay in your comfort zone, the comfort zone decays around you. In order to build intelligence or even to keep what you have, you need to be building new rooms, outside your comfort zone. If you consume a new media source in the morning, experiment with a new route to work, eat a new food for lunch, talk to a new person, or…try a NEW puzzle, you’re forcing your brain to rewire itself to be able to deal with these new experiences—you’re growing new neurons and forcing your old ones to scramble to create new connections.

Here’s what that means for your brain-training regimen: doing a puzzle is little more than busywork; it’s the act of figuring out how to do it that makes you smarter. Sit down and read the directions. If you understand them immediately and know how you should go about solving a puzzle, put it down and look for something else…something new. It’s not just use it or lose it. It’s use it in a novel way or lose it. Try it. Your brain will thank you for it.

Garth Sundem works at the intersection of math, science, and humor with a growing list of bestselling books including the recently released Brain Candy: Science, Puzzles, Paradoxes, Logic and Illogic to Nourish Your Neurons, which he packed with tasty tidbits of fun, new experiences in hopes of making readers just a little bit smarter without boring them

into stupidity. He is a frequent on-screen contributor to The Science Channel and has written for magazines including Wired, Seed, Sand Esquire. You can visit him online or follow his Twitter feed.

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development.

Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

]]>

Scientists are becoming more interested in trying to pinpoint precisely what’s going on inside our brains while we’re engaged in creative thinking. Which brain chemicals play a role? Which areas of the brain are firing? Is the magic of creativity linked to one specific brain structure? The answers are not entirely clear. But thanks to brain scan technology, some interesting discoveries are emerging. ScriptPhD.com was founded and focused on the creative applications of science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising, fields traditionally defined by “right brain” propensity. It stands to reason, then, that we would be fascinated by the very technology and science that as attempting to deduce and quantify what, exactly, makes for creativity. To help us in this endeavor, we are pleased to welcome computer scientist and writer Ravi Singh’s guest post to ScriptPhD.com. For his complete article, please click “continue reading.”

Before you can measure something, you must be able to clearly define what it is. It’s not easy to find consensus among scientists on the definition of creativity. But then, it’s not easy to find consensus among artists, either, about what’s creative and what’s not. Psychologists have traditionally defined creativity as “the ability to combine novelty and usefulness in a particular social context.” But newer models argue that these type of definitions, which rely on extremely-subjective criteria like ‘novelty’ and ‘usefulness,’ are too vague. John Kounios, a psychologist at Drexel University who studies the neural basis of insight, defines creativity as “the ability to restructure one’s understanding of a situation in a non-obvious way.” His research shows that creativity is not a singular concept. Rather, it’s a collection of different processes that emerge from different areas of the brain.

In attempting to measure creativity, scientists have had a tendency to correlate creativity with intelligence—or at least link creativity to intelligence—probably because we believe that we have a handle on intelligence. We believe can measure it with some degree of accuracy and reliability. But not creativity. No consensus measure for creativity exists. Creativity is too complex to be measured through tidy, discrete questions. There is no standardized test. There is yet to be a meaningful “Creativity Quotient.” In fact, creativity defies standardization. In the creative realm, one could argue, there’s no place for “standards.” After all, doesn’t the very notion of standardization contradict what creativity is all about?

To test creativity, researchers have historically attempted to test divergent thinking, an assessment construct originally developed in the 1950s by psychologist J. P. Guilford, who believed that standardized IQ tests favored convergent thinkers (who stay focused on solving a core problem), rather than divergent thinkers (who go ‘off on tangents’). Guilford believed that scores on IQ tests should not be taken as a unidimensional measure of intelligence. He observed that creative people often score lower on standard IQ tests because their approach to solving the problems generates a larger number of possible solutions, some of which are thoroughly original. The test’s designers would have never thought of those possibilities. Testing divergent thinking, he believed, allowed for greater appreciation of the diversity of human thinking and abilities. A test of divergent thinking might ask the subject to come up with new and useful functions for a familiar object, such as a brick or a pencil. Or the subject might be asked to draw the taste of chocolate. You can see how it would be very difficult, if not impossible to standardize a “correct” answer.

Eastern traditions have their own ideas about creativity and where it comes from. In Japan, where students and factory workers are stereotyped as being too methodical, researchers are studying schoolchildren for a possible correlation between playfulness and creativity. Nath philosopher Mahendranath wrote that man’s “memory became buried under the artificial superstructure of civilization and its artificial concepts,” his way of saying that that too much convergent thinking can inhibit creativity. Sanskrit authors described the spontaneous and divergent mental experience of sahaja meditation, where new insights occur after allowing the mind to rest and return to the natural, unconditioned state. But while modern scientific research on meditation is good at measuring physiological and behavioral changes, the “creative” part is much more elusive.

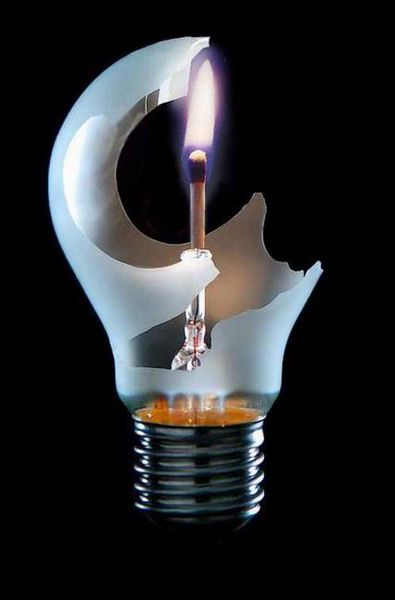

Some western scientists suggest that creativity is mostly ascribed to neurochemistry. High intelligence and skill proficiency have traditionally been associated with fast, efficient firing of neurons. But the research of Dr. Rex Jung, a research professor in the department of neurosurgery at the University of New Mexico, shows that this is not necessarily true. In researching the neurology of the creative process, Jung has found that subjects who tested high in “creativity” had thinner white matter and connecting axons in their brains, which has the effect of slowing nerve traffic. Jung believes that this slowdown in the left frontal cortex, a brain region where emotion and cognition are integrated, may allow us to be more creative, and to connect disparate ideas in novel ways. Jung has found that when it comes to intellectual pursuits, the brain is “an efficient superhighway” that gets you from Point A to Point B quickly. But creativity follows a slower, more meandering path that has lots of little detours, side roads and rabbit trails. Sometimes, it is along those rabbit trails that our most revolutionary ideas emerge.

You just have to be willing to venture off the main highway.

We’ve all had aha! moments—those sudden bursts of insight that solve a vexing problem, solder an important connection, or reinterpret a situation. We know what it is, but often, we’d be hard-pressed to explain where it came from or how it originated. Dr. Kounios, along with Northwestern University psychologist Mark Beeman, has extensively studied the the “Aha! moment.” They presented study participants with simple word puzzles that could be solved either through a quick, methodical analysis or an instant creative insight. Participants are given three words then are asked to come up with one word that could be combined with each of these three to form a familiar term; for example: crab, pine and sauce. (Answer: “apple.”) Or eye, gown and basket. (Answer: ball)

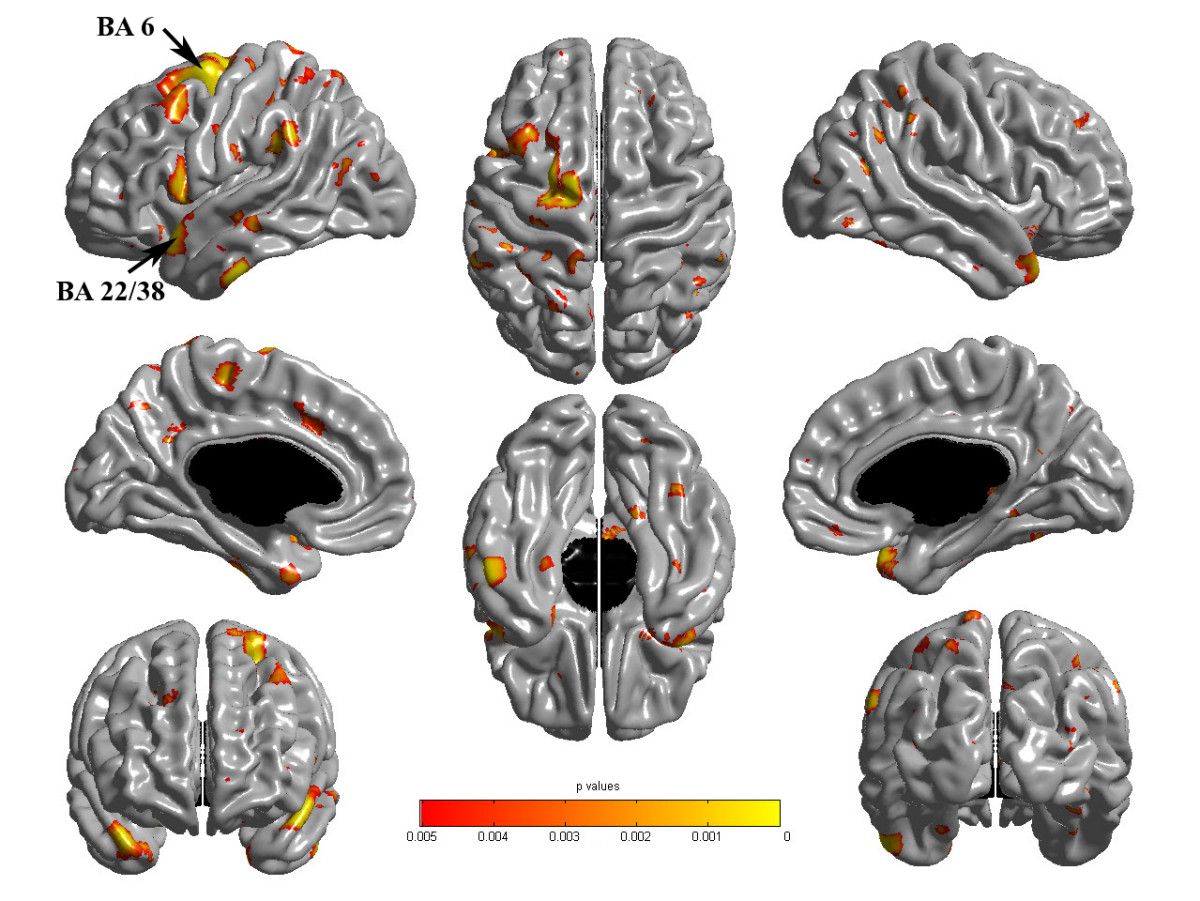

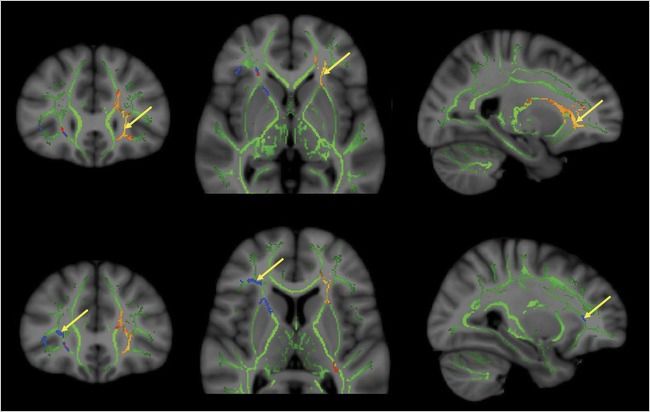

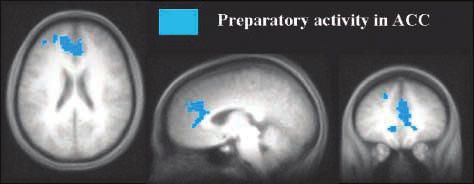

About half the participants arrived at solutions by methodically thinking through possibilities; for the other half, the answer popped into their minds suddenly. During the “Aha! moment,” neuroimaging showed a burst of high-frequency activity in the participants’ right temporal lobe, regardless of whether the answer popped into the subjects’ minds instantly or they solved the problem methodically. But there was a big difference in how each group mentally prepared for the test question. The methodical problem solvers prepared by paying close attention to the screen before the words appeared—their visual cortices were on high alert. By contrast, those who received a sudden Aha! flash of creative insight prepared by automatically shutting down activity in the visual cortex for an instant—the neurological equivalent of closing their eyes to block out distractions so that they could concentrate better. These creative thinkers, Kounios said, were “cutting out other sensory input and boosting the signal-to-noise ratio” to enable themselves retrieve the answer from the subconscious.

Creativity, in the end, is about letting the mind roam freely, giving it permission to ignore conventional solutions and explore uncharted waters. Accomplishing that requires an ability, and willingness, to inhibit habitual responses, take risks. Dr. Kenneth M. Heilman, a neurologist at the University of Florida believes that this capacity to let go may involve a dampening of norepinephrine, a neurotransmitter that triggers the fight-or-flight alarm. Since norepinephrine also plays a role in long-term memory retrieval, its reduction during creative thought may help the brain temporarily suppress what it already knows, which paves the way for new ideas and discovering novel connections. This neurochemical mechanism may explain why creative ideas and Aha! moments often occur when we are at our most peaceful, for example, relaxing or meditating.

The creative mind, by definition, is always open to new possibilities, and often fashions new ideas from seemingly irrelevant information. Psychologists at the University of Toronto and Harvard University believe they have discovered a biological basis for this behavior. They found that the brains of creative people may be more receptive to incoming stimuli from the environment that the brains of others would shut out through the the process of “latent inhibition,” our unconscious capacity to ignore stimuli that experience tells us are irrelevant to our needs. In other words, creative people are more likely to have low levels of latent inhibition. The average person becomes aware of such stimuli, classifies it and forgets about it. But the creative person maintains connections to that extra data that’s constantly streaming in from the environment and uses it.

Sometimes, just one tiny stand of information is all it takes to trigger a life-changing “Aha!” moment.

Ravi Singh is a California-based IT professional with a Masters in Computer Science (MCS) from the University of Illinois. He works on corporate information systems and is pursuing a career in writing.

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development.

Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

]]>

…a nanoscientist’s quest to mimic Nature’s molecular blueprints

Have you ever found yourself entranced by the exquisite beauty and complexity of living things? Like the intricacies of a budding flower, or the mesmerizing patterns on a butterfly’s wing? Have you ever wondered: “what are living things made of?” Are these materials just as beautiful if we were to zoom way way in and look at the actual molecular building blocks that make up life? Take a look at the interactive link The Scale of Things to see just how small the building blocks of life really are! Well the answer is “OMG – totally!” All living things share a ubiquitous set of molecular building materials we call proteins, and they are absolutely stunning! They are not only smashingly beautiful to look at, they are capable of performing a mind-numbing myriad of very intricate and complex functions that are essential to life. In a very special guest post, leading nanoscience Professor Ron Zuckermann of the renowned Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory recounts his life’s mission as a chemist to try and build artificial microscale sheets made up of nature’s very own building blocks—proteins. Everything you wanted to know about what nanotechnology is, exactly, why engineering proteins is the science of the future, and what we plan to use these discoveries for, under the “continue reading” cut.

I am a Materials Scientist working in a nanoscience research institute called The Molecular Foundry. A fundamental problem in nanoscience is how to make man-made materials with a similar level of precision and complexity at the molecular level found in nature. I am interested in applying lessons from the world of protein structure to practical man-made materials. If we are successful, we should be able to make materials that are cheap and rugged like a piece of plastic, yet be able to perform highly sophisticated functions, like recognizing a molecular partner with high specificity, or even catalyzing chemical transformations. Such materials could be used to make sensors for the detection of harmful chemicals, or as robust medical diagnostics that could survive harsh conditions, say in an underdeveloped nation. In a nutshell, we aim to make artificial proteins. This is an incredibly difficult problem, and one I have been working on for more than 20 years now. Sound a bit ambitious, or maybe a bit crazy? As I will describe in this article, it may actually be quite possible if we break the problem down into bite size chunks. The challenge comes down to two fundamental things: design and synthesis.

Protein architecture

When I look at the molecular structure of a protein molecule, I see an architectural blueprint that has survived untold generations of evolution and optimization. How then do we break open the hidden rules in these structures and use them to guide us in the design of man-made materials? Over the past several decades, scientists have used the biophysics techniques of X-ray crystallography and nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (NMR) to determine the exact three-dimensional (3D) structure of thousands upon thousands of proteins. What’s cool is that these are all available for anyone to look at (for free!) and study in the Protein Data Bank.

The most fundamental thing to notice is that nearly all protein structures share the following characteristics: (1) they are made of a linear polymer chain that is folded into a precise 3D structure and (2) they are comprised of only 20 simple molecular building blocks called amino acids, arranged in an exact sequence along the polymer chain. When we think of a ‘polymer’ we think of a long chain of repeating chemical building blocks (called monomers) found in materials like nylon or polyethylene. Such man-made materials are incredibly useful and ubiquitous now in our environment (plastic bags or saran wrap, for example). But nature beat us to the punch a long, long time ago. Biopolymers, like proteins and nucleic acids are fundamentally way more sophisticated than man-made polymers. Even though they share the same basic architecture – a linear chain of chemical building blocks – biopolymers contain information encoded in their monomer sequence. This is not unlike the way we store information in a computer. But instead of a long string of 1’s and 0’s, nature uses long polymer chains of either 4 nucleotides (the building block units of RNA and DNA), or 20 amino acids (the building block units of proteins). These 20 chemically distinct amino acid building blocks are arranged in a particular order along the chain that we refer to as the protein’s “sequence.” This sequence is powerful because in many cases it provides all the information or “molecular instructions” necessary for the polymer chain to fold up into a precisely defined 3-dimensional structure. Once folded, the protein is poised and ready for action. The fields of Structural Biology and Protein Folding have revealed the exact way that proteins fold to form local “secondary” structures, called alpha helices and beta sheets, and how these assemble together to create the fully folded protein structure. Think all this sounds a bit too complicate? Try visiting FoldIt, a really fun video game where you can actually learn all about protein folding!

Protein Mimicry

If we ever hope to create man-made protein-like materials, it is safe to assume that we will need a polymer system that shares some of the basic protein-like characteristics: for example, they will need to have a sizable set of chemically diverse monomer building blocks that can be arranged in a particular order along a linear polymer chain of at least 50 monomers long. This is a quite a tall order simply from a chemical synthesis perspective. Moreover, once we are over that hurdle, design tools will be needed to help us figure out which sequences to make.

In the early 1990s, I invented a way to synthesize a new family of non-natural polymers we called “peptoids.” I had just graduated from UC Berkeley with a PhD in organic chemistry and joined a start-up biotechnology company to develop new technologies to accelerate drug discovery. We developed peptoids to be potential therapeutic drugs. The cool thing about peptoids is that the building blocks are very very close in structure to Nature’s amino acids, but different enough to be much more rugged. They can be made from very cheap and simple chemical building blocks, and they can be made in any predetermined sequence you want. We soon developed robotic synthesizers to automatically synthesize these materials for us (see below).

Before long we discovered that short peptoid chains (just 3 monomers long) could have potent biological activities and showed promise as drug candidates. But what really floored me was that the peptoid synthesis chemistry we developed worked so efficiently that we could link over 50 monomers together, one after the other. This means each building block was being attached to a growing chain with an incredible accuracy of over 99.5%! This was exactly the tool we needed to begin the quest for creating artificial proteins. We had discovered the most efficient and practical way to make non-natural polymers of a specific sequence. This was completely awesome!

There was only one problem – the company I worked for had no interest in such a bold quest into basic science. How could such a pursuit lead to a moneymaking product in a few months? In 2006 I moved to Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory where I set out in earnest to search for artificial proteins. Fortunately, tackling difficult problems in basic science is much more the norm here. And more good news – my previous employer was kind enough to donate my robots to me. Armed with this technology to synthesize peptoid polymers, we turned to the next daunting task: which sequence of monomers should we make? It turns out that there are an absolutely astronomical number of possible peptoid sequences that can be made. Consider that there are several hundred building blocks to choose from at each of the 50 positions of a polymer chain. This means there are over 100 to the 50th power potential sequences to choose from. This is more than the number of atoms in the universe! What was a chemist to do?

Like Oil and Water

To help us focus our sequence design, we once again turned to nature. A long-time collaborator and friend of mine, Professor Ken Dill of UC San Francisco has studied protein structure in detail for decades, and has distilled some fundamental rules that are universal to all protein structures. He notes that protein structures are like globes with a water-loving surface and a water-hating (or oil-like) interior. The bottom line is you can basically lump each amino acid in the protein’s sequence into one of two categories: oil-like or water-like. This simple classification can tell you whether an amino acid is located on the inside or the outside of the protein.

The amazing thing about this insight is that it’s like looking at a protein wearing X-ray glasses! Instead of seeing 20 different “colors” of amino acids, we see only two: black and white. We are back to a simple binary code—like 1’s and 0’s. This makes it much easier to see the secret patterns hidden within the sequence. In fact, many researches have convincingly demonstrated that these binary patterns are simple, plentiful and predictable.

So with our handy X-ray glasses on we returned our gaze to the peptoid structure problem. We realized that all our sequence recipe needed was a touch of Dill! This meant we could greatly simplify our search for the right peptoid sequence. We needed to only consider two, diametrically opposed building blocks: water loving and water hating.

Nanosheets

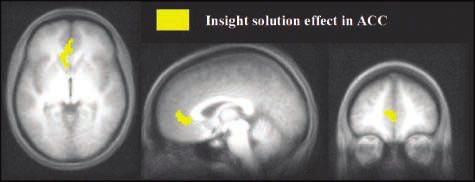

Inspired by these insights, we set out to find the right sequence patterns that would result in a precisely ordered structure in a non-natural peptoid polymer. We began to systematically unlock the sequence code by using our robots to synthesize all the possible repeating patterns of these two disparate building blocks. We reasoned that if we were to make something precisely ordered, it would “crystallize” into something that we could see. Fortunately we have really powerful electron microscopes in my building. So we started cranking through all the possible sequence patterns, dissolving up each new sequence in some water and taking it down to the basement to look at them really close up.

Now it is a little nuts to think that we could make something precisely structured from a peptoid polymer, since it is known that each strand is about as stiff as a piece of overcooked spaghetti. And as one might expect, most of our sequences looked really messy and gooey. But very soon we saw something quite striking. In one particular sample, we saw large, flat paper-like objects with sharp, straight edges. And they were floating around everywhere in the solution. An unexpected sight to be sure!

Fast-forward another year of making careful measurements and reproducing the results over and over. We determined that these sheets were only two molecules thick, and yet millions and millions of molecules wide. We had discovered the largest and thinnest organic crystals ever! We were able to use one of the most powerful electron microscopes in the world in the National Center of Electron Microscopy, to look directly at the individual polymer chains that make up the crystal. We could see these chains wiggle around and slide against one another as if they were alive. No one had ever seen such detail before – a truly awe-inspiring sight!

We were able to use many kinds of advanced analytical tools to tell us that these nanosheets were indeed very special. They have the same kind of ordered structure that a protein has: they have a defined inside and outside, and we know almost exactly where each atom is located in the structure. Essentially, we discovered the sequence code that programs the polymer chain to form a 2D sheet. No doubt there are more complex codes waiting to be discovered that will form even more sophisticated structures. This discovery was recently reported in the journal Nature Materials, and was picked up by the more mainstream publications WIRED.com and Chemical & Engineering News. These sheets are likely to be important for all kinds of potential applications. Their discovery is kind of like the invention of ‘molecular plywood’: a new kind of nanoscale building material from which we can engineer even more complex molecular architectures. It’s amazing what kind of beauty you can create from simple building blocks!

Basic research like this can move seemingly very slowly, which makes the occasional breakthrough like this all the more meaningful and exciting. It reaffirms for me that it is so important to listen to and cultivate your inner curiosity, surround yourself with like-minded people, and aim high. With enough patience and persistence, wonderful things await discovery!

Take a look at a brief video of Dr. Zuckermann explaining his lab’s nanosheet discovery:

Ron Zuckermann is the Facility Director of the Biological Nanostructures Facility at Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory. Dr. Zuckerman also provides numerous consulting services at the intersection of chemistry, biology and engineering.

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development.

Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

]]>

Begun in 2008 by Columbia University Physicist Brian Greene, the World Science Festival has burgeoned from an intimate cluster of science panels to a truly integrated mega-event melding culture, science, and the arts. Those lucky enough to make it out to New York City to the over 40 events this year will have a chance to learn about a variety of current science topics, go stargazing with NASA Scientists, discuss Faith and Science, and find out why humans commit violent crimes. Those not lucky enough to be there can browse the full list of events here and watch a live-stream of selected events here. ScriptPhD.com is proud to be at the festival, and will be bringing you coverage through Sunday through the eyes of talented science writers Jessica Stuart and Emily Elert. Our blogging will include event summaries, photographs, interviews and even videos of the street fairs and science literally spilling over into the streets of New York.

OPENING NIGHT GALA — June 2, 2010

The 2010 World Science Festival began tonight with a gala celebration at Avery Fisher Hall in Lincoln Center. The grand venue played host to a number of luminaries, among them Alan Alda, Yo-Yo Ma, Kelli O’Hara, and the star of the evening, legendary physicist Stephen Hawking.

Alda started off the evening. “It seems strange that with how much we know, how much is known about science, so little reaches us, the general public…” He continued, “Science is still obscured by a black hole of misunderstanding, and when light tries to escape, it gets drawn back in.” The World Science Festival’s goal is to “cultivate and sustain a general public informed by the content of science, inspired by its wonder, convinced of its value, and prepared to engage with its implications for the future.” Judging by the line up they have this coming week, they’ll do a great job of that again this year.

The opening gala opening brought out a wide variety of people. From Nobel Prize winners to Broadway stars, the house was packed. Musical numbers all tied into the science theme. Broadway singers Rebecca Luker and Kelli O’Hara charmed the room, with “When the Sea is all around Us” and “Stardust,” respectively. Yo-Yo Ma and the Silk Road Ensemble played a lively Persian-inspired version of the Icarus story.

Undoubtedly, the highlight of the evening was honoree Stephen Hawking.

“Back in 1965, when I first saw the skyscrapers of Manhattan, I had been recently diagnosed with ALS and had a 2 year life expectancy. Therefore, no one is more surprised or delighted than myself to be back here 45 years later…”

Hawking has long been interested in bringing science to the public. Along with countless scientific publications, he’s written several books for the layperson, including his bestseller A Brief History of Time, and the updated A Briefer History of Time. His introduction this evening featured a clip of him from The Simpsons (He’s appeared in several episodes – tonight’s clip was from the Season 16 episode “Don’t Fear the Roofer”).

Those who know Dr. Hawking spoke of his wit and humanity. His sense of humor came through in his brief remarks.

“For my honeymoon in the 60’s, I brought Jane to a physics conference here in New York. It seemed to be both a logical and romantic destination. However, I have since learned that logic and romance do not always go together as well as I once believed. Some things cannot be solved by algebra, I am sorry to say.”

PIONEERS OF SCIENCE — June 3, 2004

Early this morning, just a block away from Times Square, a group of 21 lucky middle and high school students gathered to chat with astrophysicist Dr. James Mather. They were joined via video chat by students from Florida, Kansas, and students from two schools in Ghana who traveled more than 3 hours from their rural towns to participate.

As the students prepared for the chat to begin, they wrote out and practiced the questions they wanted to ask with their friends. One young man approached Dr Mather in awe, “Oh my god, it’s such an honor to meet you!” “It’s an honor to meet you, too,” he replied. Dr. Mather is by all accounts a brilliant scientist. He’s the recipient of a 2006 Nobel Prize in physics, and is the Senior Project Scientist on the James Webb Space Telescope, slated to launch in 2014 (which is currently on exhibit in Bryant Park and which we will be bringing you video coverage of). He’s also a fantastic communicator, easily bridging the gap between high level NASA science and the inquiries of young students. As question after question came his way, he distilled his answers to clearly explain how the universe, and the tools we’ve built to understand it, work.

This group of bright students from around the globe kept him on his toes, asking questions such as “How is it possible to have an infinite amount of space? What contains it?” and “What does COBE do exactly?” They asked about how cosmic microwave background affects society, and how scientists see back in time to look at dust from the big bang. He answered many questions with more questions, and did not shy away from saying he did not know some answers, an important aspect of being a good, inquisitive scientist.

Dr. Mather explained to the students the mysteries of dark matter and dark energy, how we could use the presence of oxygen to detect other life in space, and the challenges they faced when they had to redesign the new telescope after the Challenger explosion, reducing the weight by half and finding a new rocket to send the now foldable telescope up on.

When asked “Did you ever think you’d be an astrophysicist when you were young?” Dr Mather replied “I didn’t even know what one was…” Towards the end, the conversation turned to how students could become scientists themselves. “You find something that interests you, and you follow it…Some people want to solve crossword puzzles all day long, and so they become experts at crossword puzzles… some people become fascinated with science, and they follow some special interest.” Mather continued, “Einstein wanted to know about compass needles. I wanted to know about stars… You just have to follow what interests you, and pretty soon you are led to, ‘I really want to know more math, because math is part of science’, and then ‘I need to know other parts of science that relate to my part of science’, and so, you just follow what you want to do, and try to get people to help you, and I see that everybody here already has had some help, because you got here. My impression is that there’s a lot of help available for people who want it, and if you say ‘I want to study science,’ somebody will say ‘I want to help you study science.’ So perhaps that’s the most important thing to know, that people want to help you if you want to do this.” He finished by telling the students to look him up and feel free to email him with more questions.

As the talk concluded, the remote locations signed off, and the students in New York swarmed the front of the room, buzzing with excitement and basking in the attention of this true Pioneer of Science.

OUR GENOMES, OURSELVES — June 3, 2010

Few medical issues are fraught with as much controversy as genomic testing. Will it lead to designer babies? Could knowing what’s in your DNA hurt your chances of getting insurance or a job? What would you do if you found out you had BRCA1, the “breast cancer” gene?

Our Genome Ourselves (https://www.worldsciencefestival.com/our-genomes-ourselves) tackled all of these questions and more.

Panelists included Francis Collins (Geneticist, Physician, & Director of the NIH), George Church (Molecular geneticist), and Robert C. Green (Neurologist & Epidemiologist), with moderator Richard Besser (ABC News Senior Health and Medical Editor, former acting director of CDC and Physician). All experts in the field of genomics, these four men offered both broad medical and policy knowledge, and a truly compelling panel presentation.

The biggest takeaway, repeated by all of the panelists, is that very very few genes are deterministic – that is, there are not many conditions that can be indicated or eliminated by the presence or absence of one single gene mutation. Each person has some 6 billion genes in each cell. The vast majority of traits and predispositions are caused by a combination of factors, many of which are not fully understood. We are still in the very early stages of being able to interpret what a sequenced genome might indicate – even if you were fully sequenced tomorrow, it would be very prudent to revisit the interpretation next week and next month and next year. The sequence of letters should stay the same (barring any typographical errors), but what they might indicate for your future could be drastically different, based on new information being found daily.

Many people think that if they find out what their DNA says, they’ll have a road map for the diseases they’ll get and the life they’ll live, but in almost every case, that couldn’t be further from the truth. Without taking into account environment and other factors, we have a huge over-expectation of what genomics can tell us. There are other issues, too, beyond interpretation. Many emotional, ethical, and educational factors come into play. What about testing our children? At what point do they have the right to know they’re likely to get Parkinsons? Dr. Green wondered if it’s wise to give people results that say they have a 40% greater chance of a disease? What if that actually means their overall odds go from 1% to under 2%? A very important side question – do people understand statistics well enough to truly understand what risks indicated by genetic markers are saying?

Dr. Collins pointed out that typically, when considering what we want to know about our own personal genomic sequence, we consider three things:

1. What kind of risk is it able to provide you with?

2. What’s the burden of the disease?

3. Is there an intervention?

The panelists agreed that as genetic testing becomes more prevalent, we need to provide proper training to medical professionals, whether that be physicians, physicians assistants, nurse practitioners, or others, to properly explain the meaning of the results to patients. We also need to improve and implement a solid electronic medical record system, so that the results can be applied. Minorities and other under-served populations need to be recruited to donate their DNA, which likely means dealing with the practicality of being able to promise privacy to those who are more skeptical than the original volunteers of interested researchers.

Some of the bigger questions can be easily answered. For now, the idea of being able to go to a geneticist and selecting a tall, blue-eyed, muscular son, with musical abilities, athletic prowess, and above average intelligence, is out of the picture. Too many factors go into each one of those traits for it to be easily selectable – it’s currently impossible to optimize an embryo for those types of genes. The Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act of 2008 provides a legal framework so that Americans cannot be discriminated against based on genetic information, as it pertains to health care and employment. As for what individuals will decide to do if they’re shown to have BRCA1, that will remain a personal decision.

The first draft of the human genome sequence was completed on June 26, 2000. Twenty years later, we’ve come so far, yet still know so little. It will be fascinating to see what science achieves in another couple of decades.

Follow the World Science Festival on Facebook and Twitter. All photography ©ScriptPhD.com. Please do not use without permission.

Jessica Stuart is a writer, photographer and videographer living in New York City. Find her on her personal blog, and Twitter.

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development.

Follow us on Twitter and our Facebook fan page. Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

]]>

Dr. Mark Changizi, a cognitive science researcher, and professor at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, is one of the most exciting rising stars of science writing and the neurobiology of popular culture phenomena. His latest book, The Vision Revolution, expounds on the evolution and nuances of the human eye—a meticulously designed, highly precise technological marvel that allows us to have superhuman powers. You heard me right; superhuman! X-ray vision, color telepathy, spirit reading, and even seeing into the future. Dr. Changizi spoke about these ideas, and how they might be applied to everything from sports stars with great hand-eye coordination to modern reading and typeface design with us in ScriptPhD.com’s inaugural audio podcast. He also provides an exclusive teaser for his next book with a guest post on the surprising mindset that makes for creative people. Read Dr. Changizi’s guest post and listen to the podcast under the “continue reading” cut.

You are an idea-monger. Science, art, technology—it doesn’t matter which. What matters is that you’re all about the idea. You live for it. You’re the one who wakes your spouse at 3am to describe your new inspiration. You’re the person who suddenly veers the car to the shoulder to scribble some thoughts on the back of an unpaid parking ticket. You’re the one who, during your wedding speech, interrupts yourself to say, “Hey, I just thought of something neat.” You’re not merely interested in science, art or technology, you want to be part of the story of these broad communities. You don’t just want to read the book, you want to be in the book—not for the sake of celebrity, but for the sake of getting your idea out there. You enjoy these creative disciplines in the way pigs enjoy mud: so up close and personal that you are dripping with it, having become part of the mud itself.

Enthusiasm for ideas is what makes an idea-monger, but enthusiasm is not enough for success. What is the secret behind people who are proficient idea-mongers? What is behind the people who have a knack for putting forward ideas that become part of the story of science, art and technology? Here’s the answer many will give: genius. There are a select few who are born with a gift for generating brilliant ideas beyond the ken of the rest of us. The idea-monger might well check to see that he or she has the “genius” gene, and if not, set off to go monger something else.

Luckily, there’s more to having a successful creative life than hoping for the right DNA. In fact, DNA has nothing to do with it. “Genius” is a fiction. It is a throw-back to antiquity, where scientists of the day had the bad habit of “explaining” some phenomenon by labeling it as having some special essence. The idea of “the genius” is imbued with a special, almost magical quality. Great ideas just pop into the heads of geniuses in sudden eureka moments; geniuses make leaps that are unfathomable to us, and sometimes even to them; geniuses are qualitatively different; geniuses are special. While most people labeled as a genius are probably somewhat smart, most smart people don’t get labeled as geniuses.

I believe that it is because there are no geniuses, not, at least, in the qualitatively-special sense. Instead, what makes some people better at idea-mongering is their style, their philosophy, their manner of hunting ideas. Whereas good hunters of big game are simply called good hunters, good hunters of big ideas are called geniuses, but they only deserve the moniker “good idea-hunter.” If genius is not a prerequisite for good idea-hunting, then perhaps we can take courses in idea-hunting. And there would appear to be lots of skilled idea-hunters from whom we may learn.

There are, however, fewer skilled idea-hunters than there might at first seem. One must distinguish between the successful hunter, and the proficient hunter – between the one-time fisherman who accidentally bags a 200 lb fish, and the experienced fisherman who regularly comes home with a big one (even if not 200 lbs). Communities can be creative even when no individual member is a skilled idea-hunter. This is because communities are dynamic evolving environments, and with enough individuals, there will always be people who do generate fantastically successful ideas. There will always be successful idea-hunters within creative communities, even if these individuals are not skilled idea-hunters, i.e., even if they are unlikely to ever achieve the same caliber of idea again. One wants to learn to fish from the fisherman who repeatedly comes home with a big one; these multiple successful hunts are evidence that the fisherman is a skilled fish-hunter, not just a lucky tourist with a record catch.

And what is the key behind proficient idea-hunters? In a word: aloofness. Being aloof—from people, from money, from tools, and from oneself—endows one’s brain with amplified creativity. Being aloof turns an obsessive, conservative, social, scheming status-seeking brain into a bubbly, dynamic brain that resembles in many respects a creative community of individuals. Being a successful idea-hunter requires understanding the field (whether science, art or technology), but acquiring the skill of idea-hunting itself requires taking active measures to “break out” from the ape brains evolution gave us, by being aloof.

I’ll have more to say about this concept over the next year, as I have begun writing my fourth book, tentatively titled Aloof: How Not Giving a Damn Maximizes Your Creativity. (See here and here for other pieces of mine on this general topic.) In the meantime, given the wealth of creative ScriptPhD.com readers and contributors, I would be grateful for your ideas in the comment section about what makes a skilled idea-hunter. If a student asked you how to be creative, how would you respond?

Mark Changizi is an Assistant Professor of Cognitive Science at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in New York and the author of The Vision Revolution and The Brain From 25,000 Feet. More of Dr. Changizi’s writing can be found on his blog, Facebook Fan Page, and Twitter.

ScriptPhD.com was privileged to sit down with Dr. Changizi for a half-hour interview about the concepts behind his current book, The Vision Revolution, out in paperback June 10, the magic that is human ocular perception, and their applications in our modern world. Listen to the podcast below:

~*ScriptPhD*~

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology

in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development.

Follow us on Twitter and our Facebook fan page. Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

]]>

Here at ScriptPhD.com, we pride ourselves on being different, and we like thinking outside the mold. So for Earth Day 2010, we wanted to give you an article and a perspective that you wouldn’t get anywhere else. There is no doubt that we were all bombarded today with messages to be greener, to use less, to be more eco-conscious, and to respect our Earth. But what is the underlying effect of advertising that collectively promotes The Green Brand? And has the Green Brand started to overshadow the very evil—environmental devastation—it was meant to fight to begin with? What impact does this have on the future of the Green movement and the advertising agencies and media that are its vocal advocates? These are questions we are interested in answering. So when we recently met Matthew Phillips, a Los Angeles-based writer, social media and branding expert, and the founder of a new urban microliving movement called Threshing, we were delighted to give him center stage for Earth Day to offer his insights. What results is an intelligent, esoteric and thoughtful article entitled “Plastic Beads and Sugar Water,” sure to make you re-evaluate everything you thought you knew about going green. We welcome you to contribute to (and continue) the lively conversation in the comments section.

“Access to land provides access to food, clothing, and shelter—which means access to land provides the possibility of self-sufficiency—if anyone wants to maintain a dependent (and therefore somewhat dependable) workforce, it’s crucial for you to sever their access to land. It’s also crucial that you destroy wild foodstocks: why would I buy salmon from the grocery store if I could catch my dinner from the river? Now, with people having been effectively denied access to free food, clothing, and shelter, which means having been effectively denied access to self-sufficiency, if they are going to eat, they’re gong to have to buy their food, which means they’re going to have to go to work to get the cash to buy what they need to survive. If you’re a corporation, you’ve got them where you want them.” —What We Leave Behind.

I have a great deal of admiration for our original permaculture engineers, the American Indians, all grass fed bison advocates. Looking back, we can’t imagine how naive or gullible they were to accept fire, water, plastic beads and useless trinkets in exchange for their healthy animals, fresh fruits and vegetables, consulting knowledge, and land—whose value is incalculable. Interestingly, here we are 518 years later, and we’ve all been duped into giving up our valuables for well marketed sugar water, and filtered tap… in plastic bottles.

After 1492 the American colonization effort was dominated by the European nations. In the 19th century alone, 50 million people left Europe for the Americas with ‘old world’ diseases, and a manifesto to massacre, obliterating 42 million American Indians. Everything changed; the landscape, population, plant and animal life. A few pioneers with rebel attitudes proved they could kill, conquer, and dominate an entire people and their land. What have we learned? When you deprive a group of people access to their land, you dominate and control their self-sufficiency, and ultimately their sustainability.

Earth Day was designed from its inception, April 22, 1970, to inspire awareness and appreciation for the Earth’s environment. Like all successful grassroots movements, Earth Day continues to self-organize and experiences annual growth. Over the years, it has propagated thousands of related causes or brands. This celebration gives us the opportunity to contemplate how to purchase food and drink that are produced locally through natural, sustainable methods. Whether we graze together, or barbecue grass-fed bison, I anticipate that many foodborne conversations will thresh organic ideas that seed new urban backyard businesses, and energize sustainable causes.

In fact, in this past year, we have witnessed local production and sustainable social causes grab the wheel from the generic “Green” brand. ‘Local and sustainable’ terms have the potential to drive significant impact in helping redefine a movement whose banding terminology is arguably out-of-focus. The Green goal has not achieved our Garden of Eden fantasy. Many generic Green causes have become distracted watching, and often joining, the fight against their ‘evil,’ instead of cultivating community and encouraging positive purposeful action. We’ve seen new Green causes sprout through PR dusting designed to crowd out similar already established causes. There’s nothing wrong with competition, seeking a bigger audience, news, press, and ultimately funding, but often the next new Green cause articulates greater Green evils in an attempt to further establish its reason to rally. This problem is churned up further with traditional reports broadcasting emotionally charged sound bites. Reporters often don’t take the effort to dig past the easy emotional approach, and into the rich cream of the cause itself. It is much easier to philosophize about the negative, which can feed our illusion of intellectual superiority, but it’s really keeping our callus-free hands from getting dirty planting GM-free maze in the garden and producing oxygen. “The creation of something new is not accomplished by the intellect but by the play instinct acting from inner necessity. The creative mind plays with the objects it loves,” said Carl Jung.

A great brand seeks to unify in a cyclical system: Magnetizing believers, educating, generating action, and finally producing evangelists, who then magnetize new believers and so on. Memorable brands are most effective when they are communicating their power and concept through story. At its most basic, a brand’s story is made up of the hero, (relating to the brand’s reputation and hopefully positive recognition), and its evil, (the perception of what hinders recognition of the brand). Clarifying the adversaries of the brand can help to ‘rally the troops,’ codifying their cause and movement. Without an adversary, it’s often difficult to get enough of a rouse from fellow partners to get anything started.

Every great brand needs an evil to fight, but Green’s evil has metastasized into the most unimaginable catastrophe that no cause could ever compete against—an over heating planet. Since it doesn’t get much worse than a gooey globe due to our ongoing abuse, this heat enemy seemed guaranteed to become THE unifying force, an evil that we could all fight together to overcome. The problem is the scope is too large to control or confine. It has mutated. Proving global warming has the potential to fracture the green community, and along the way has produced a number of serious critics. Terms like ‘climategate,’ and climate skeptics like Doug Keenan, continue to look at research they say is embellished to promote climate change. Maybe worshiping the over heating demon has made the ‘Green’ brand seem boring compared to the excitement of the fight. Google never defined its “Don’t be Evil,” last minute tag, which is part of the reason it continues to generate conversations across the board. Google has essentially allowed all of us to insert our own definitions of evil, which in effect has unified greater numbers to their brand. A very novel approach.

If the evil of a brand consistently gains more press than the cause, then the evil assumes and replicates the identity of the brand. When this happens, the brand is no longer the host. When the evil forcefully sucks all the nourishment from the brand’s beating heart, then the evil we were fighting becomes the cause. We feel more comfortable with our fingers on the keyboard dealing intellectually with evil, which in effect, removes our foot from the shovel of physical, sweaty action. Do we want to get back to the heart of the brand, the original cause? Harley Davidson, once perceived as the brand of choice for rebels and tattooed ex-cons, re-branded itself and become the hog of choice for everyone who could scrape together enough money, regardless of prison experience, body type, tattoo placement, or gender. Even our kids wear official HD branded fashion with pride.

If we stop promoting the evils, real or manufactured, and start encouraging positive actions and solutions, (often positive action is the best offense against perceived evil anyway) we’ll find passionate people that want to join us in healing our people and planet. The strategic approach to refresh a brand is extremely important if it is to succeed. Digitally empowered consumers want to punish those that don’t behave in a socially responsible way and reward those that do. Social media has given people real power to act, and also to be negative. “Social media is inherently more negative than a positive medium on many levels,” said David Jones, the global chief executive of Havas Worldwide. “Lots of stuff that is passed around is negative. If you are a brand or a company today you should be far less worried about broadcast regulations than digitally empowered consumers.”

Many will continue to base their directive on creating new enemies, using ‘the fight’ to impassion those around them to rally their cause. Stop depleting the ozone layer, reduce your carbon footprint, global warming. All grand Green, but terminology that is technically fear-focused. We’ve heard the pitch: “It is your investment of $59.95 that allows us to partner together to fight this injustice.” The fear based, negative approach is almost always wrong, (unfortunately, it can be effective) . It’s a slippery slope, and those who don’t fully embrace the creed, are either stamped ‘stupid,’ or ostracized. But sustainability should be positive at its core. There is a time to debate, and we’ve debated ourselves into the greatest recession any of us have ever experienced. It’s time to stop debating.

Let’s begin by forming communities that build sustainable ventures together. If we are fighting, or politicking, we are not building. “We have become divided into so-called red and blue states, an outcome directly traceable to the urban-rural division of our society. This is something of a simplification, but food producers and their social allies tend to vote red and food consumers and their social allies tend to vote blue. The division is thought to be between conservative and liberal philosophies, but it much more reflects the difference between rural and urban values,” said Gene Logsdon.

There are two real challenges within the sustainability movement:

1) Consumers’ decisions (especially with food) are splintered by: A) Convenience, B) Tradition, C) Bias, and D) Beliefs.

2) Industry’s “manufactured demand” is affecting consumers with: A) Deceptive advertising, B) Ambiguous terminology, C) Perfectly designed plastic convenience packaging sealing our addictive lifestyles.

The minute we wake up we are subjected to an eco-plastic, part of this complete breakfast, 100% edible, industrialized high fructose corn syrup, brand campaign. Industrialized conveyor belts are pumping out a marketing product of starch coated with refined sugar. We can reignite our camaraderie by producing fruits, vegetables, animals and vehicles that not only compete, but surpass, our current available choices; all sponsored of course by our very green desire for sustainability. Incidentally, the average number of ‘green’ products per store almost doubled between 2007 and 2008. Green advertising almost tripled between 2006 and 2008. Does this necessarily mean we are heading in the right direction?

Governmental regulations for consumer protection in industrial food processing plants have only added to an already over stressed food system. This industrialized hyper-efficiency has caused diseases in animals and bugs on crops that have been taken so far out of their natural ecosystem that they can no longer produce without heavy use of antibiotics and pesticides. These measures, of course, were designed to keep us safe, but instead have become another major concern since “packaged nourishment” comes from the industrialized, often treated, food system.

Creatives are beginning to find and tell the stories concerning the overly subsidized and industrialized food and distribution system which favors use of pesticides and antibiotics. Since the government historically is not very good at spearheading movements, artists (media pioneers, authors) and social entrepreneurs will continue to fill this leadership role. We don’t have to look far to see powerful results. Thank the documentary filmmakers of Food Inc., Supersize Me, HomeGrown, The Future of Food, Story of Stuff, and Bottled Water, for helping us become visually aware of how industries have been deceiving consumers and themselves in their interest of greed and everyone’s desire for convenience. But there is hope, and it’s simple. Consumers are communicating online like never before, this leads to uniting together to strategically direct where we spend our hard earned bread and where we plant or raise our own food.

Jamie Oliver’s new TV series, The Food Revolution, has exposed the frozen fat underbelly of pre-packaged (brown and gold) foods, and government charts that officially dictate the clogging of our kids in school. Local and “real” food production and consumption has become a legitimate genre, with universities, and high schools requiring reading of titles like Barbara Kingsolver’s Animal, Vegetable, Miracle, Michael Pollan’s Omnivore’s Dilemma, Bill McKibben’s Deep Economy, among others. These authors are helping us move past intellectual reasoning and into action. Since Timothy Ferrass taught us how to achieve a four hour work week, some of us among the fortunate now have the extra time to plant some seeds, water, and grow great big vegetables, and share them with our friends and neighbors.

I believe that in the next decade we will see less of an emphasis on extrinsic, materialistic values and more on intrinsic, spiritual values. This shift in emphasis will begin to bear fruit with the collaborative grafting between creative media pioneers and social entrepreneurs who seek to disrupt the status-quo. Research from San Francisco State University has shown that experiences bring people more happiness than material possessions. Experiences shared with others continue to provide even greater happiness through memories long after the event occurred. I believe many social entrepreneurs and creative media pioneers, in their hearts, believe their core purpose is to encourage our return to a sustainable world ecosystem. In other words, many will forgo Hummer-sized riches in order to nurture the successful adoption of their creations into society. There remains however ambiguity in the complexity that lies between the producer and the consumer. The ancient system of distribution gives middlemen the leverage to manipulate both producers and consumers. This too is evolving, as producers return to their roots and begin to distribute locally. There is change in the air, spring is coming.

We are at such a nascent stage in the evolution of the sustainable movement. The infrastructure necessary for the modern city to relocate to the farm is exorbitant, but the farm is beginning to integrate into the metropolis, one yard at a time. ‘Off the grid’ produces many wonderful connotations. It is an adventurous subject, one that I’m convinced will help propel this branding conversation forward. I wonder who else is discussing the connections of the ideas from this article, and from the authors and media pioneers mentioned? Who are the artisans, and social entrepreneurs that are working on this? Very curious about your thoughts. Please don’t hesitate to email me, and please act.

Let’s continue to find new ways to unify this brand with wonderful heart felt stories about the adventures of locally produced products, urban farms, and sustainability.

Writing this has given me a renewed appreciation for early American Indian cave drawn stories of food: adventure, and victory. There is more there than I had imagined.

Matthew Phillips is a media producer, writer and technologist working in Los Angeles, CA. He is the producer of Threshing.

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development.

Follow us on Twitter and our Facebook fan page. Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

]]>

All right class, settle down, settle down. My name is Mr. Ross, but you may call me BR. Welcome to Pop-Culture Science 101. I know what many of you are thinking: “Science is boring; I just don’t get it.” I can understand those sentiments. But that’s only because of the ways you’ve been taught in the past. Today is going to be different. On this, the third day of the Science Week collaboration between ScriptPhD and CC2K, we decided to have a bit of silly fun and cover a couple of traditionally esoteric science topics from an angle I doubt any of you have considered before—pop culture icons. So get out your notebooks and pens, today’s lesson begins now! Please click “continue reading” for more.

Lesson 1: Genetics/Evolutionary Theory

It’s easy to get intimidated if you hear terms like Neodarwinism and Mendelian genetics. If I say deoxyribonucleic acid polymerase, well, I might as well be speaking Swahili, right? Heck, you might not even know who Charles Darwin was, or why his work is so important to biology. Doesn’t matter. Forget the technical jargon; don’t worry about the minutiae. The essentials of genetics and evolutionary theory can be learned simply by considering the X-Men. Yes, I mean the comic book superhero team.

The X-Men are superheros not because they’re aliens or because they were exposed to some kind of radiation, but because they were born as such. They bear mutations in the so-called X gene (yes this is make-believe, but for the purpose of today’s lesson it will work just fine). A gene is nothing more than a unit of information in your DNA that instructs something. Eye color. Hair color. How tall you are. Basically everything that makes us unique (and that makes us human, as opposed to some other species) is because of our genes. In the case of the X-Men X gene, mutations herein can bestow superpowers, though, this isn’t always the case.

See, mutation is a random thing. Mutations in genes can be negative as well as positive, debilitating just as often as advantageous. The key here is to consider how a mutation affects an organism’s fitness to survive. Ah, did that ring some bells? Some of you comic book fans might be thinking of the X-Men’s arch-enemy Apocalypse and his fanatic devotion to the concept of the “survival of the fittest.” The man (or mutant, rather) is a strong proponent of Darwin and his theory on evolution by natural selection. I know that might sound complicated, but it’s really not. Let’s go back to the X-Men. Consider the following:.

Let’s compare Wolverine with some average mutant Joe Schmoe off the street. Wolverine’s X gene mutation grants him numerous super powers including enhanced strength, speed, senses, claws, and an extraordinary healing ability. Joe Schmoe (for the sake of argument) has a mutation in the X gene that has bestowed him with, let’s say a prehensile tail (i.e. a tail like that of a monkey). That’s it. He’s not super strong, he can’t climb trees particularly well, he’s just a guy with a tail.

Now for the selective pressure. Senator Kelly teams up with some other unsavory types in the government and creates the Sentinels, giant robots programmed to detect and eliminate mutants with extreme prejudice. I ask you, who will have the better chance to survive? Who is more fit? Joe Schmoe, or Wolverine? Obviously Wolverine. Chance has given him a mutation that makes him more likely to survive a selective pressure (the Sentinels) than our pal Joe, hence Wolverine is more likely to reproduce and pass on his mutation to his offspring. That, friends, is evolution.

Lesson 2: Acid-Base Chemistry

One of my favorite chemistry teachers growing up was a mullet-coiffed action escape artist by the name of MacGyver. His lessons were so memorable because they were practical applications of chemistry using common household items to resolve extraordinary situations. Granted, the majoritysome of his lessons exaggerated the bounds of what was truly possible (sometimes Mac was more about style than substance), but often his lessons were grounded firmly in reality.

Take, for example, the time he demonstrated how to make a fire extinguisher from simple items found in an ordinary kitchen, and gave a lesson on acid-base reactions in the process (episode 132, “Good Knight MacGyver”).

Let’s say for the sake of dramatic storytelling (this IS a science in entertainment site, after all!) that your parents are going out of town, and you’ve decided to have a few friends over (including Dylan, that totally cute guy in your English Lit. class you’re hoping will ask you to prom). You decide that in order to elevate your little party above run-of-the-mill get-togethers you’re going to make your very own mozzarella sticks and jalepeno poppers. You fill a pot with vegetable oil and turn the burner all the way to “hi”. You’re ready to do some serious frying.

But then you get distracted, and the oil heats to the point of ignition. Your attention is pulled away from your cell phone by smoke coming from the kitchen. You have a grease fire to deal with. If you burn your parents’ house down they’ll ground you until you’re 30. You have to act fast. You quickly turn off the stove burner, and you know that if you throw water on the fire it will just make it worse. You could put it out if you had a fire extinguisher, but your parents don’t keep one in the house. Then you remember MacGyver’s chemistry lesson.

Acting quickly, you open the fridge and pull out the half-full bottle of Diet Coke and the box of baking soda your mom put in there because the Arm & Hammer commercials assert it will help remove unwanted odors. Then you pull out the large bottle of white vinegar from under the sink that hardly ever gets used. You pour the Diet Coke out onto the floor and fill the 32-ounce Coke bottle with as much baking soda as you can get in there (you notice it’s almost 3/4 full). Now comes the tricky part.

You quickly pour vinegar into the bottle, cover the opening with your thumb, give it a quick shake, and point it at the fire. Bubbly liquid begins to shoot out of the mouth of the bottle. You sweep the bottle back and forth, noticing with relief that the bubbly liquid is putting out the fire. There’s some smoke damage and one heck of a mess to clean up (and that party is definitely canceled), but catastrophe has been averted!

As to why this works, let’s open up our Unofficial Macgyver How-To Handbooks to Chapter 3, page 70:

Fire extinguishers work by removing one of the critical ingredients for a fire: oxygen. When vinegar is combined with baking soda, the two react and produce carbon dioxide gas or CO2. This type of reaction is known in chemistry as an acid-base reaction, and the vinegar (the acid) and baking soda (the base) model is a high school chemistry classic:

NaHCO2 (baking soda/base) + CH3COOH (vinegar/acid) –> CO2 (gas) + H2O (water) + Na (Sodium) + CH3COO (a combination of hydrogen, carbon and oxygen that we like to call “magic dust”)