“It’s like a war. You don’t know whether you’re going to win the war. You don’t know if you’re going to survive the war. You don’t know if the project is going to survive the war.” The war? Cancer, still one of the leading causes of death despite 40 years passing since the National Cancer Act of 1971 catapulted Richard Nixon’s famous “War on Cancer.” The speaker of the above quote? A scientist at Genentech, a San Francisco-based biotechnology and pharmaceutical company, describing efforts to pursue a then-promising miracle treatment for breast cancer facing numerous obstacles, not the least of which was the patients’ rapid illness. If it sounds like a made-for-Hollywood story, it is. But I Want So Much To Live is no ordinary documentary. It was commissioned as an in-house documentary by Genentech, a rarity in the staid, secretive scientific corporate world. The production values and storytelling offer a tremendous template for Hollywood filmmakers, as science and biomedical content become even more pervasive in film. Finally, the inspirational story behind Herceptin, one of the most successful cancer treatments of all time, offers a testament and rare insight to the dedication and emotion that makes science work. Full story and review under the “continue reading” cut.

For biotechnology and pharmaceutical companies, it is the best of times, it is the worst of times. On the one hand, many people consider this a Golden Era of pharmaceutical discovery and innovation for certain illnesses like cancer. Others, such as HIV, receive poor grades for drug and vaccine development. Furthermore, the FDA recently passed much more stringent controls on drugs brought to market, leaving some to posit that this will have a negative impact on future pharmaceutical breakthroughs. And while a recent documentary chronicles some of the unhealthy profits of the pharmaceutical industry, the enormous cost of developing and bringing medicines to market is often gravely overlooked. Today, the pharmaceutical industry as a whole has one of the lowest favorability scores of any major industry, despite some impressive social contributions, partnerships and global health investments. Much of this public hostility simply comes down to the fact that people don’t know very much about the pharmaceutical industry, notoriously reluctant to publicize or reveal anything about their inner workings.

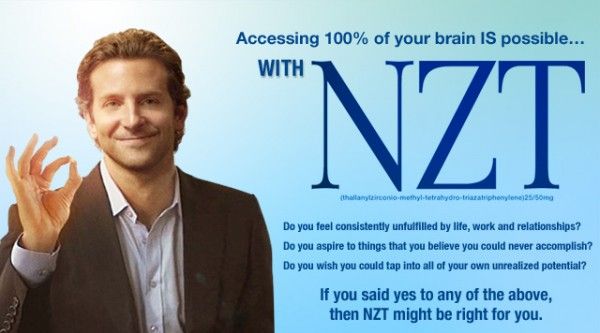

Science in Hollywood is experiencing no such crisis. In many ways, it is a golden age for science, technology and medicine in film, with more big-budget mainstream films exploring themes and content germane to 21st Century science than ever before. Last year alone, three smart hit movies broached the realities, hopes and anxiety of the technological times we live in, each in a very different way. The stylish and ambitious thriller Limitless explored the possibility of a limitless brain capacity through pharmacopeia, a magical pill that would maximize one’s intelligence and allow 100% brain function around the clock. Certainly echoing the credo of the modern pharmaceutical movement—there is a pill that can solve every problem, whether it’s been invented or not—Limitless fell slightly short in condemning (or even properly acknowledging) the impracticalities ethical irresponsibility of developing such a drug, especially in its ending. Stephen Soderbergh’s surgical and pinpoint-accurate epic Contagion gave audiences a spine-chilling, terrorizing purview into the medical and public health realities of a modern-day pandemic. But while it strove, and succeeded, in showcasing how government agencies, university labs and medical establishments would contend with and fight off such a global disaster, Contagion was never able to connect audiences emotionally either with the characters impacted by the pandemic or with the scientists battling it. No recent movie is a better example of delicate introspection and exposition than the brilliant, poignant, funny and difficult 50/50. On the heels of CNN pondering whether Hollywood could take on cancer came a film that did so with reality, grace and even humor. Partially because it was based on screenwriter Will Reiser’s own brush with cancer, 50/50 set aside the clinical as a secondary backdrop to examine the psychological.

Each of the films above has an important quality that is be an essential component to effective Hollywood science storytelling – scientific accuracy, emotional connection to the outside world and an overview of biomedical impact and innovation. We recently screened an industry documentary, filmed at the request of Genentech scientists, called I Want So Much To Live, that is an excellent blueprint for the way we’d like to see scientific stories portrayed in film. Best of all, it doesn’t sacrifice the human story for the technical one, nor the very real complex emotions that scientists, engineers and doctors feel when they develop and market potentially life-saving technology.

The miracle of Herceptin is really a decade-long journey that started in the labs of UCLA, moved to the pharmaceutical labs of San Francisco, endured countless obstacles, street riots and controversies to end up as one of the most revolutionary breakthroughs in breast cancer treatment research history. Advances in cancer insight always seem to come in evolutionary leaps. For example, the cellular mechanism of how normal cells become cancerous was unknown until Harold Varmus and Michael Bishop established the presence of retroviral oncogenes, genes that control cellular growth and replication. When either disrupted or turned on, these genes contribute to the transformation of normal cells into tumors. Other than the discovery of as an anti-estrogen treatment for breast cancers, relatively little new ground had been gained in fighting the disease. Scientists continued to be perplexed why some women were cured by chemotherapy, which tries to stop cancer cell division by attacking the most rapidly-dividing cells in the body, while others didn’t respond at all. It was not until the late 80s that scientists Alex Ullrich and Michael Shepherd (both featured in the film) discovered that about 20-30% of early-stage breast cancers express amplify a gene called HER-2, a protein embedded in the cell membrane that helps regulate cell growth and signaling. With the help of UCLA scientist Dennis Slamon, famously portrayed by Harry Connick, Jr. in a made-for-TV movie about the development of Herceptin, the scientists soon developed an anti-HER-2 antibody that significantly slowed tumor growth.

An early Phase I clinical trial was conducted simply to establish safety, with 20 volunteers. The lone survivor, still alive to this day, was given 10 weeks to live. Phase II trials honed in on dosage and establishing that the drug performed its intended effects. This time, out of 85 volunteers, 5 survived completely, not a bad result, but not enough for the FDA and the science community. The scientists took a huge risk for their Phase III study. They combined their anti-HER-2 antibody with current treatment. The results were astounding. Out of 450 patients, 50% survived — the highest ever success rate for metastatic cancer!

Think the story ends here? Think again. This is where it just begins to take more emotional twists and turns than a fictitious Hollywood script. Unlike many Hollywood productions, though, the human impact angle was shared equally between all the players in this evolving story, easily this documentary’s most powerful aspect. In order to test their Phase III trials of Herceptin (in concert with chemotherapy treatments available at that time), Genentech had to establish a highly controversial lottery system to pick those who would receive highly limited life-saving quantities of Herceptin, and those who would be categorized in the control studies, and thereby handed a death sentence. So controversial was the lottery system, that it engendered televised protests in the Bay Area, along with anguished pleas from dying patients—the documentary’s title is the first sentence of one such letter: “I want so much to live.” The scientists at Genentech were hardly immune to the weight of each decision, either. They were tormented over the fairness of the lottery system, producing enough high-quality treatment to pass the clinical trial, and even in keeping an unbiased eye on the science to save lives in the long run. Talking about the pressure of those days reduced one of the scientists to tears. And after all was said and done, the lone FDA scientist entrusted with the power to oversee the Herceptin study and green light its approval as a drug? She had just lost her mother to breast cancer. These intertwining fortunes are summarized by executive producer Christie Castro: “By definition, groups of people are imperfect. But those who worked on Herceptin proved that the complexity – indeed, the fantastic mess – that simply comes with being human can sometimes result in something truly worthwhile.”

One of the first patients to get the experimental Herceptin treatment prior to FDA approval, though not profiled in the movie, is flourishing well over a decade after being diagnosed with the most aggressive form of breast cancer. Stories like hers lie at the emotional heart of the I Want So Much To Live story (and Genentech’s motivation for continuing the controversial studies):

Herceptin was officially approved as a drug on September 22, 2000. On October 20, 2010, Herceptin was approved as an adjuvant (joint) treatment with current chemotheraphy drugs for the treatment of aggressive breast cancer. To date, the adjuvant therapy has had an impressive 58% success rate for a cancer that once carried an unlikely rate of survival for those afflicted.

Take a look at the trailer for I Want So Much To Live:

The powerful and well-crafted content of this documentary should serve as a valuable template for how the multi-faceted power of storytelling can be used across multiple industries. It smartly tells a gripping scientific story without either dumbing down the science or elevating it beyond a layperson’s understanding—a certain goal for the increasing amount of cinematic fare such as Contagion. It provides a functional breakdown of the enormous challenges and technical obstacles of the pharmaceutical drug development process. Like many other aspects of science, it is mysterious to the general public, out of their grasp and seemingly always occuring behind closed doors. Especially at a time when public perception of the pharmaceutical industry is at an all-time low, such transparency could strengthen reputations and increase business. “Corporations are,” executive producer Christine Castro reminds us, “groups of people who have ideas, ambitions, conflicts and dreams, and, at the end of the day, a desire to see their work result in something meaningful. That’s why we decided to take a creative chance and face the potential skepticism that a corporation would or could tell an unvarnished story about itself.”

Finally, the film develops a three-dimensional emotional tether to the three different sides impacted by the scientific process: scientists, the agencies that regulate them and society as a whole. There doesn’t always have to be a tacit bad guy, and sometimes, this protagonistic complexity makes for the best story of all. Holder, who started filming I Want So Much To Live around the same time that her late brother was diagnosed with a rare and virulent form of cancer, echoed our sentiment as she reflected on the process of making the film. It allowed her to discover “that science is a creative pursuit as well as a technical one; that science is beautiful and can be accessible; and that anyone, at any time, might have the idea that could one day save lives.”

We can only hope that the harmony of creativity, passion and emotion devoted to all sides of the drug discovery process within this film translates to more private and studio productions dealing with complex scientific and socio-technological issues.

ScriptPhD.com caught up with filmmaker Elizabeth Holder, who directed and produced I Want So Much To Live. Here are some of her thoughts on putting together this incredible story and interacting with the scientists and heroic patients that made it happen:

ScriptPhD.com: Can you tell me where the seeds of inspiration for the story of the drug Herceptin first arose, and what inspired you to tackle this material for your documentary?

Elizabeth Holder: The initial idea to make a documentary film about Herceptin came from executive producer Chris Castro, who upon joining Genentech in 2007 thought that the story would make a compelling documentary film. (She will have to share with you her experience.) I first heard about the project from a friend and began doing research on Herceptin and Genentech. I was excited to work on this film; excited to jump into and explore a new world. My first inspiration came from the people who were the story; the passionate men and women who faced adversity with courage and perseverance, never swaying from their pursuit, making difficult decisions laced with moral and ethical ramifications. I knew this story of individual and collective growth would resonate with many, and would be especially poignant to the employees of Genentech. (This at the time was the intended audience for the film.) When I began working on this film in 2008 I had no idea how personal this journey would become and how connected I would be to the people I would meet and the story I was going to tell.

While I was making the film, my younger brother David was battling cancer – a rare type of cancer for a 33 year old man. While I was meeting with scientists and learning about biotech and drug development for the movie, David was fighting the disease with everything science and medicine could offer. He wrote a blog about his journey, signing off each entry with the words “Plow On”. Each day, I would hope that the scientists would hurry up. Figure it out. But I learned firsthand that science is not a “hurry up” business and that many people are doing everything they can to find ways to stop cancer. My wish is that the film serves to inspire everyone who is on the frontlines in the battle against cancer, to encourage them to keep on fighting the good fight, no matter what, and even on a bad day, to Plow On.

SPhD: How willing were the patients and scientists to contribute to the project?

EH: As you can imagine, everyone, especially scientists, are skeptical. Some people took a bit more convincing than others, but once they started talking, the interviews, both on and off camera, were amazing.

I am grateful to the patients, scientists, activists, executives, and doctors for honestly and enthusiastically sharing their stories, perspective, and experience with me. I quickly became indebted to mentors and colleagues who diligently and without judgment explained and re-explained molecular biology and the drug development process to me. I hope the determination and delight in which they approach their work is reflected in the film.

SPhD: Any of your own preconceived notions that were shattered or altered throughout the making of this film?

EH: I discovered striking similarities between scientists and filmmakers which I did not expect to find. A research scientist and a filmmaker must each imagine an idea, convince others to recognize the value of funding the idea, and then prove the concept. Like many filmmakers, the scientists I met were impassioned about their work and showed great determination in the face of extraordinary odds. Like filmmaking, drug development takes a village. Before making this film I had no idea how many years and how many people it took to develop a drug; the process involves a huge collaborative effort between massive numbers of people in multiple organizations, in various countries.

It was incredible and amazing to me that the scientists would talk about “cells” and “exxons” and “nucleotides” as if they could actually be seen by the human eye. It was also inspiring to me that a scientist is committed enough to work on a research project for their whole career with the knowledge that they might not ever see an outcome in their lifetime. And finally, I was pleased to confirm (though not statistically proven) that a lot of really smart and accomplished people do not have perfectly clean desks.

SPhD: Within the movie, we get a real feel for the dichotomy between the emotional appeals of the desperately ill patients, the cautious, careful FDA scientists, and the Genentech researchers who want to make sure the product they introduce is safe for patients. Was this a thematic element you foresaw or that developed as you pieced the film together?

EH: I carefully planned out the film, yet also left room for new discoveries along the way. (I was constantly learning – from each filmed interview, from advisors, from books.) For each defining moment in the film I made sure to film at least three people talking about the same experience with different opinions. I wanted to make sure that the topic was covered from various perspectives so I could intercut interviews together. I knew that I was not going to use narration. I only wanted people who were part of the story to be telling the story; to engage the audience with their firsthand accounts. I wanted the audience to feel connected emotionally to each person in the film, to empathize with the person on screen even if they disagreed with their tactic and/or goal. Additionally, I knew I was going to use archival footage, photos and authentic documents to organically reveal the isolation and miscommunication, the unwitting partnerships, the building mistrust and the eventual coming together. When I first saw and read the pile of letters saved by Geoff, I knew that I would use it in the film. I carried a few of those letters with me to every interview and pulled them out when it felt right, asking people to read them and respond. The scene was assembled to show how incorrect assumptions lead to strife; to show how each person’s journey was critical to the whole story; and to show how those intertwining stories eventually became the framework for the work that is continuing today.

SPhD: What are your own thoughts on the lottery system that Genentech ultimately used to determine who would be eligible to participate in the Herceptin clinical trials?

EH: I see both sides of the issue, and don’t think there is an easy answer. When interviewing people for this film, I went into each interview with a clean slate, without having any pre-conceived agenda or opinion. It was critical that I empathized with each person and was able to tell the story though the objectives and needs of those who I interviewed, those who had direct experience. I needed to be able to fully see and feel the situation from their point of view. And, to me, judgment is only something that pulls us apart, not together. I am thankful I am in the documentary business and not in the business of making the kind of decisions that had to be made during that time. I am not sure what I would have done if someone I loved needed the drug before it was approved.

~*ScriptPhD*~

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development.

Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.