In 2011, a cognitive supercomputing system developed at IBM named “Watson” was pitted against, and subsequently defeated, two of the most successful Jeopardy! game-show contestants of all time. A project five years in the making, Watson was initially developed as a “Grand Challenge” successor to Deep Blue, the machine that beat Gary Kasparov at chess, and was a prototype for DeepQA, a question/answer natural language analysis architecture. Since his Jeopardy! triumph, however, Watson has been successfully applied towards improving health care, oncology, business applications and soon enough… even education. At the same time that IBM has been expanding Watson’s cognitive computing abilities, they’ve also been brilliantly marketing him to the general public through a series of traditional and interactive ads.

As part of our ongoing “Selling Science Smartly” series, we analyze the Watson campaign in more depth and feature an exclusive and insightful podcast conversation with the IBM marketing team behind it.

Campaign: Watson

Agency: IBM/Ogilvy&Mather

Industry: Cognitive computing/information technology

Quick thought experiment. Name at least a couple of technology advertising campaigns (not including Apple) that have been so memorable and clever, they either compelled you to buy a product or piqued your curiosity to learn more about it. Chances are, you can’t. For one thing, outside of computers and gadgets, “big picture” technologies like cloud computing, artificial intelligence and artificial neural networks have still not become fully mainstream. For another, like many high-end sophisticated science applications, it is difficult to communicate such abstract applications in bite-size pieces. IBM’s recent Watson campaign, centered around its powerful cognitive question/answer (QA) computing device, defies conventional tech branding. It’s instantaneously attention-getting. It features Watson’s attributes by incorporating one of the hallmark rules of film-making/screenwriting: show, don’t tell. Most importantly, humans are the centerpiece of each commercial/spot, which is an important antidote to Hollywood-induced fears of robotic takeover and a more realistic depiction of how we will really subsume AI into our existence through small steps.

Here is Watson summarizing his seemingly endless array of capabilities for integration of deep learning:

Here is Watson explaining his capacity for improving digital health and diagnostics in medicine to an adorable young patient:

Recently, Watson displayed his technological versatility in an interactive campaign where he helped design a supermodel’s “Cognitive Dress.” The dress was equipped with lighting to monitor real-time social media reactions and represents an example of augmenting the creative process with technology in the future.

Why It’s Good Science Advertising

Whether he’s enjoying a one-on-one conversation with virtually any human, designing dresses or helping people cook gourmet meals, Watson comes across as versatile, approachable and interactive. Soon, Watson will even produce meta-advertising, in the form of cognitive marketing — enabling consumers to have remote brand-related conversations with Watson Ads suited to their individual needs and questions about a particular product. As illustrated in the video below, the Watson campaign, like the technology itself, represents a total commitment to brand awareness, IBM’s core mission and the eventual potential of the cognitive technology device. And, it’s memorable!

Why It Works

With a cognitive machine as powerful and versatile as Watson, brand messaging presents two major challenges: succinctly communicating the complex framework of solutions for consumers, businesses and institutions, and doing so in an emotionally engaging manner. Watson succeeds on both accounts. He describes his capabilities from a first-person perspective, not through omniscient narration. He functions through interlocution, which lends an intimacy to the commercials — any one of us might find ourselves interacting with Watson and requesting his help. He is fun and funny; brilliant yet adorably inept in human slang; cheeky yet serious; always helpful, curious and collaborative. In essence, Watson has been branded as an anthropomorphic companion instead of a sterile robot. 21st Century technology will inevitably be personal, inclusive and integrated into our lives. The Watson campaign feels like the realistic unveiling of the cognitive computing era. Take a look at Watson’s conversation with Ridley Scott about artificial intelligence, as portrayed in Hollywood (referenced in our podcast below):

What Other Science Campaigns Can Learn From This One

Creative risk-taking is essential for successfully marketing sophisticated technology, not just in the content itself, but in how it is crafted. In the immediate predecessor to the Watson campaign, a series of spots entitled “Made With IBM” traveled across three continents to share short, documentary-like stories about cross-applications of a panoply of IBM technology and its relevance in today’s connected world. Accordingly, the aggregate Watson ads and interactive spots present an engaged, personalized look at how cognitive computing will facilitate faster, more improved and easier tasks in all areas of human life in the future while making an immediate impact in several industries right now. Indeed, IBM’s commitment to incorporating storytelling across all of its content extends to the unusual move of hiring screenwriters to join its marketing team. IBM also partnered with the TED Institute for multi-year thought leadership symposium where critical ideas related to technology and data-driven computing, along with the ways they could change the world, were shared by leading experts. In the process, this multi-platform approach not only taps into the next generation of consumers, but slowly assuages understandable reservations about artificial intelligence.

To help gain insight into the creative development and thought process behind the Watson campaign, as well as the greater context of using didactic advertising and thought leadership to inform about complex technology, ScriptPhD.com was joined for a conversation with IBM’s Vice President of Branded Content and Global Creative Ann Rubin and Watson Chief Marketing Officer Stephen Gold. Listen to our podcast below:

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development. Follow us on Twitter and Facebook. Subscribe to our podcast on SoundCloud or iTunes.

Ray Bradbury, one of the most influential and prolific science fiction writers of all time, has had a lasting impact on a broad array of entertainment culture. In his canon of books, Bradbury often emphasized exploring human psychology to create tension in his stories, which left the more fantastical elements lurking just below the surface. Many of his works have been adapted for movies, comic books, television, and the stage, and the themes he explores continue to resonate with audiences today. The notable 1966 classic film Fahrenheit 451 perfectly captured the definition of a futuristic dystopia, for example, while the eponymous television series he penned, The Ray Bradbury Theatre, is an anthology of science fiction stories and teleplays whose themes greatly represented Bradbury’s signature style. ScriptPhD.com was privileged to cover one of Ray Bradbury’s last appearances at San Diego Comic-Con, just prior to his death, where he discussed everything from his disdain for the Internet to his prescient premonitions of many technological advances to his steadfast support for the necessity of space exploration. In the special guest post below, we explore how the latest Bradbury adapataion, the new television show The Whispers, continues his enduring legacy of psychological and sci-fi suspense.

Premiering to largely positive reviews, ABC’s new show The Whispers is based on Bradbury’s short story “Zero Hour” from his book The Illustrated Man. Both stories are about children finding a new imaginary friend, Drill, who wants to play a game called “Invasion” with them. The adults in their lives are dismissive of their behavior until the children start acting strangely and sinister events start to take place. Bradbury’s story is a relatively short read with just a few characters that ends on a chilling note, while The Whispers seeks to extend the plot over the course of at least one season, and to that end it features an expanded cast including journalists, policemen, and government agents.

The targeting of young, impressionable minds by malevolent forces is deeply disturbing, and it seems entirely plausible that parents would write off odd behavior or the presence of imaginary friends as a simple part of growing up. In both the story and the show, the adults do not realize that they are dealing with a very real and tangible threat until it’s too late. The dread escalates when the adults realize that children who don’t know each other are all talking to the same person. The fear of the unknown, merely hinted at in Bradbury’s story, will seem to be exploited to great effect during the show’s run.

When “Zero Hour” was written in 1951, America was in the midst of McCarthyism and the Red Scare, and the fear of Communism and homosexuality ran rampant. As the tensions of the Cold War grew, so too did the anxiety that Communists had infiltrated American society, with many of the most aggressively targeted individuals for “un-American” activities belonging to the Hollywood filmmaking and writing communities. Bradbury’s story shares with many other fictions of the time period a healthy dose of paranoia and fear around possession and mind control. Indeed, Fahrenheit 451, a parable about a futuristic world in which books are banned, is also a parable about the dangers of censorship and political hysteria.

The makers of The Whispers recognize that these concerns still permeate our collective consciousness, and have updated the story with modern subject matter, expanding the subject of our apprehension to state surveillance and abuse of authority. To wit, many recent films and shows have explored similar themes amidst the psychological ramifications of highly developed artificial intelligence and its ability to control and even harm humans. Our concurrent obsession with and fear of technology run amok is another topic explored by Ray Bradbury in many of his later works. The idea that those around us are participating in a grand scheme that will bring us harm still sows seeds of discontent and mistrust in our minds. For that reason, the concept continues to be used in suspense television and cinema to this day.

One of the reasons Bradbury’s work continues to serve as the inspiration for so much contemporary entertainment is his use of everyday situations and human oddities to create intrigue. One such example is a 5-issue series called Shadow Show based on Bradbury’s work, released in 2014 by comic book publisher IDW. Some of the best artists, writers and comics had agreed to participate in this project since Bradbury had such a huge influence in their writing and art. In this anthology, Harlan Ellison’s “Weariness” perfectly elicits Bradbury’s dystopia in which our main characters experience the universe’s end. The terrifying end of life as we know it is one of Bradbury’s recurring themes, depicted in writings like The Martian Chronicles. He rarely felt the need to set his stories in faraway galaxies or adorn them with futuristic gadgets. Most of his writing focussed on the frightening aspects of humans in quotidien surroundings, such as in the 2002 novel, Let’s All Kill Constance. Much of The Whispers takes place in an ordinary suburban neighborhood, and like many of his stories, what seems at first to be a simple curiosity, is hiding something much more complex and frightening.

Fiction that brings out the spookiness inherent in so many facets of human nature creates a stronger and more enduring bond with its audience, since we can easily deposit ourselves into the characters’ situations, and all of a sudden we find that we’re directly experiencing their plight on an emotional level. That’s always been, as Bradbury well knew, the key to great suspense.

Maria Ramos is a tech and sci-fi writer interested in comic books, cycling, and horror films. Her hobbies include cooking, doodling, and finding local shops around the city. She currently lives in Chicago with her two pet turtles, Franklin and Roy. You can follow her on Twitter @MariaRamos1889.

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development. Follow us on Twitter and Facebook. Subscribe to our podcast on SoundCloud or iTunes.

From a sci-fi and entertainment perspective, 2015 may undoubtedly be nicknamed “The Year of The Robot.” Several cinematic releases have already explored various angles of futuristic artificial intelligence (from the forgettable Chappie to the mainstream blockbuster Marvel’s Avengers: Age of Ultron to the intelligent sleeper indie hit Ex Machina), with several more on the way later this year. Two television series premiering this summer, limited series Humans on AMC and Mr. Robot on USA add thoughtful, layered (and very entertaining) discussions on the ethics and socio-economic impact of the technology affecting the age we live in. While Humans revolves around hyper-evolved robot companions, and Mr. Robot a singular shadowy eponymous cyberhacking organization, both represent enthusiastic Editor’s Selection recommendations from ScriptPhD. Reviews and an exclusive interview with Humans creators/writers Jonathan Brackley and Sam Vincent below.

Never in human history has technology and its potential reached a greater permeation of and importance in our daily lives than at the current moment. Indeed, it might even be changing the way our brains function! With entertainment often acting as a reflection of socially pertinent issues and zeitgeist motifs, it’s only natural to examine the depths to which robots (or any artificial technology) might subsume human life. Will they take over our jobs? Become smarter than us? Nefariously affect human society? These fears about the emotional lines between humans and their technology are at the heart of AMC’s new limited series Humans. It is set in the not-too-distant future, where the must have tech accessory is a ‘synth,’ a highly malleable, impeccably programmed robotic servant capable of providing any services – at the individual, family or macro-corporate level. It’s an idyllic ambition, fully realized. Busy, dysfunctional parents Joe and Laura obtain family android Anita to take care of basic housework and child rearing to free up time. Beat cop Pete’s rehabilitation android is indispensable to his paralyzed wife. And even though he doesn’t want a new synth, scientist George Millikan is thrust with a ‘care unit’ Vera by the Health Service to monitor his recovery from a stroke. They can pick fruit, clean up trash, work mindlessly in factories and sweat shops make meals, even provide service in brothels – an endless range of servile labor that we are uncomfortable or unwilling to do ourselves.

Humans brilliantly weaves the problems of this artificial intelligence narrative into multiple interweaving story lines. Anita may be the perfect house servant to Joe, but her omniscience and omnipresence borders on creepiness to wife Laura (and by proxy, the audience). Is Dr. Millikan (who helped craft the original synth technology) right that you can’t recycle them the way you would an old iPhone model? Or is he naive for loving his synth Odi like a son? And even if you create a Special Technologies Task Force to handle synth-related incidents, guaranteeing no harm to humans and minimal, if any, malfunctions, how can there be no nefarious downside to a piece of technology? They could, in theory, be obtained illegally and reprogrammed for subversive activity. If the original creator of the synths wanted to create a semblance of human life – “They were meant to feel,” he maintains – then are we culpable for their enslaved state? Should we feel relieved to see a synth break out of the brothel she’s forced to work in, or another mysterious group of synths that have somehow become sentient unite clandestinely to dream of a dimension where they’re free?

In reality, we already are in the midst of an age of artificial intelligence – computers. Powerful, fast, already capable of taking over our workforce and reshaping our society, they are the amorphous technological preamble to more specifically tailored robots, incurring all of the same trepidation and uncertainty. Mr. Robot, one of the smartest TV pilots in recent memory, is a cautionary tale about cyberhacking, socioeconomic vulnerability and the sheer reliance our society unknowingly places in computers. Its central themes are physically embodied in the central character of Elliot, a brilliant cybersecurity engineer by day/vigilante cyberhacker by night, battling schizophrenia and extreme social anxiety. To Elliott, the ubiquitous nature of computer power is simultaneously appealing and repulsive. Everything is electronic today – money, corporate transactions, even the way we communicate socially. As a hacker, he manipulates these elements with ease to get close to people and to solve injustice (carrying a Dexter-style digital cemetery of his conquests). But as someone who craves human contact he loathes the way technology has deteriorated human interaction and encouraged nameless, faceless corporate greed.

Elliot works for Allstate Security, whose biggest client is an emblem of corporate evil and economic diffidence. When they are hacked, Elliot discovers that it’s a private digital call to arms by a mysterious underground group called Mr. Robot (resembling the cybervigilante group Anonymous). They’ve hatched a plan to to concoct a wide-scale economic cyber attack that will result in the single biggest redistribution of wealth and debt forgiveness in history, and recruited Elliot into their organization. The question, and intriguing premise of the series, is whether Elliot can juggle his clean-cut day job, subversive underground hacking and protecting society one cyberterrorist act at a time, or if they will collapse under the burden of his conscience and mental illness.

Humans is a purview into the inevitable future, albeit one that may be creeping on us faster than we want it to. Even if hyper-advanced artificial intelligence is not an imminent reality and our fears might be overblown, the impact of technology on economics and human evolution is a reality we will have to grapple with eventually. And one that must inform the bioethics of any advanced sentient computing technology we create and release into the world. Mr. Robot is a stark reminder of our current present, that cyberterrorism is the new normal, that its global impact is immense, and (as with the case of artificial robots), our advancement of and reliance on technology is outpacing humans’ ability to control it.

ScriptPhD.com was extremely fortunate to chat directly with Humans writers Jonathan Brackley and Sam Vincent about the premise and thematic implications of their show. Here’s what they had to say:

ScriptPhD.com: Is “Humans” meant to be a cautionary tale about the dangers of complex artificial intelligence run amok or a hypothetical bioethical exploration of how such technology would permeate and affect human society?

Jonathan and Sam: Both! On one level, the synths are a metaphor for our real technology, and what it’s doing to us, as it becomes ever more human-like and user-friendly – but also more powerful and mysterious. It’s not so much hypothesising as it is extrapolating real world trends. But on a deeper story level, we play with the question – could these machines become more, and if so, what would happen? Though “run amok” has negative connotations – we’re trying to be more balanced. Who says a complex AI given free rein wouldn’t make things better?

SPhD: I found it interesting that there’s a tremendous range of emotions in how the humans related to and felt about their “synths.” George has a familial affection for his, Laura is creeped out/jealous of hers while her husband Joe is largely indifferent, policeman Peter grudgingly finds his synth to be a useful rehabilitation tool for his wife after an accident. Isn’t this reflective of the range of emotions in how humans react to the current technology in our lives, and maybe always will?

J&S: There’s always a wide range of attitudes towards any new technology – some adopt enthusiastically, others are suspicious. But maybe it’s become a more emotive question as we increasingly use our technology to conduct every aspect of our existence, including our emotional lives. Our feelings are already tangled up in our tech, and we can’t see that changing any time soon.

SPhD: Like many recent works exploring Artificial Intelligence, at the root of “Humans” is a sense of fear. Which is greater – the fear of losing our flaws and imperfections (the very things that make us human) or the genuine fear that the sentient “synths” have of us and their enslavement?

J&S: Though we show that synths certainly can’t take their continued existence for granted, there’s as much love as fear in the relationships between our characters. For us, the fear of how our technology is changing us is more powerful – purely because it’s really happening, and has been for a long time. But maybe it’s not to be feared – or not all of it at least…

Catch a trailer and closer series look at the making of Humans here:

And catch the FULL first episode of Mr. Robot here:

Mr. Robot airs on USA Network with full episodes available online.

Humans premieres on June 28, 2015 on AMC Television (USA) and airs on Channel 4 (UK).

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development. Follow us on Twitter and Facebook. Subscribe to our podcast on SoundCloud or iTunes.

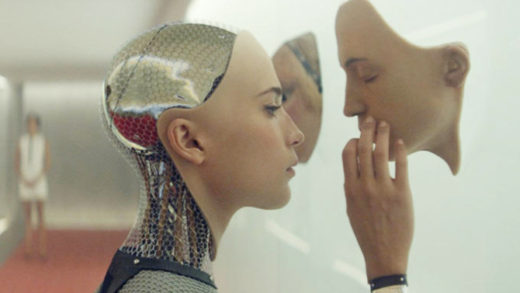

Every so often, a seminal film comes out that ends up being the hallmark of its genre. 2001: A Space Odyssey redefined space and technology in science fiction. Star Wars proved sci-fi could provide blockbuster material, while Blade Runner remains the standard-bearer for post-apocalyptic dystopia. A slate of recent films have broached varying scenarios involving artificial intelligence – from talking robots to sentient computers to re-engineered human capacity. But Ex Machina, the latest film from Alex Garland (writer of the pandemic horror film 28 Days Later and the astro-thriller Sunshine) is the cream of the crop. A stylish, stripped-down, cerebral film, Ex Machina weaves through the psychological implications of an experimental AI robot named Ava possessing preternatural emotional intelligence and free will. It’s a Hitchcockian sci-fi thriller for the geek chic gadget-bearing age, a vulnerable expository inquiry into the isolated meaning of “sentience” (something we will surely contend with in our time) and an honest reproach of technology’s boundless capabilities that somehow manages to celebrate them at the same time.

ScriptPhD.com’s enthusiastic review of this visionary new sci-fi film includes an exclusive Q&A with writer and director Alex Garland from a recent Los Angeles screening.

The preoccupation with superior artificial intelligence as a thematic idea is not a recent phenomenon. After all, Frankenstein is one of the pillars of science fiction – an ode to hypothetical human engineering gone awry. Terminator and its many offshoots gave rise to robotics engineering, whether as saviors or disruptors of humanity. But over the last 16 months, a proliferation of films centered around the incorporation of artificial intelligence in the ongoing microevolution of humanity has signaled a mainstream arrival into the zeitgeist consciousness. 2014 was highlighted with stylish and ambitious but ultimately overmatched digital reincarnation film Transcendence to the understated yet brilliant digital love story Her to the surprisingly smart Disney film Big Hero 6. This year amplifies that trend, with Avengers: Age of Ultron and Chappie marching out robots Elon Musk could only dream about among many other later releases. Wedged in-between is Ex Machina, taking its title from the Latin Deus Ex Machina (God from the machine), a film that prefers to focus on the bioethics and philosophy of scientific limits rather than the razzle-dazzle technology itself. There is still a tendency for sci-fi films concerning AI to engross themselves in presenting over-the-top science, with ensuing wholesale consequences based on theoretical technology, which ultimately hinders storytelling. Ex Machina is a simple story about two male humans, a very advanced-intelligence generated AI robot named Ava, confined in a remote space together, and the life-changing consequences that their interactions engender as a parable for the meaning of humanity. It will be looked back on as one of the hallmark films about AI.

When computer programmer Caleb Smith (Domhall Gleeson) wins an exclusive private week with his search engine company’s CEO Nathan Bateman (Oscar Isaac) it seems like a dream come true. He is helicoptered to the middle of a verdant paradise, where Nathan lives as a recluse in a locked-down, self-sufficient compound. Only Nathan plans to let Caleb be the first to perform a Turing Test on an advanced humanistic robot named Ava (Alicia Vikander). (Incidentally, the technology of creating a completely new robot for cinema was a remarkable process, as the filmmakers discussed in-depth in the New York Times.) The opportunity sounds like a geek’s dream come true, only as the layers slowly peel back, it is apparent that Caleb’s presence is no accident; indeed, the methodology for how Nathan chose him is directly related to the engineering of Ava. Nathan is, depending on your viewpoint, at best a lonely eccentric and at worst an alcoholic lunatic.

For two thirds of the movie, tension is primarily ratcheted through Caleb’s increasingly tense interviews with Ava. She’s smart, witty, curious and clearly has a crush on him. Is something like Ava even possible? Depending on who you ask, maybe not or maybe it already happened. But no matter. The latter third of the movie provides one breathtaking twist after another. Who is testing and manipulating whom? Who is really the “intelligent being” of the three? Are we right to be cautionary and fear AI, even stop it in its tracks before it happens? With seemingly anodyne versions of “helpful robots” already in existence, and social media looking into implementing AI to track our every move, it may be a matter of when, not if.

The brilliance of Alex Garland’s sci-fi writing is his understanding that understated simplicity drives (and even heightens) dramatic tension. Too many AI and techno-futuristic films collapse under the crushing weight of over-imagined technological aspirations, which leave little room for exploring the ramifications thereof. We start Ex Machina with the simple premise that a sentient, advanced, highly programmed robot has been made. She’s here. The rest of the film deftly explores the introspective “what now?” scenarios that will grapple scientists and bio-ethicists should this technology come to pass. What is sentience and can a machine even possess self-awareness? Is their desire to be free of the grasp of their creators wrong and should we allow it? Most importantly, is disruptive AI already here in the amorphous form of social media, search history and private data collected by big technology companies?

The vast majority of Ex Machina consists of the triumvirate of Nathan, Caleb and Ava, toggling between scenes with Nathan and Caleb and Caleb interviewing (experimenting on?) Ava between a glass facade. The progression of intensity in the numbered interviews that comprise the Turing Test are probably the most compelling of the whole film, and nicely set-up the shocking conclusion. In its themes of the human/AI dichotomy and dialogue-heavy tone, Ex Machina compares a lot to last year’s brilliant sci-fi film Her, which rightfully won Spike Jonze the Oscar for Best Original Screenplay. In the former, a lonely professional letter writer becomes attached to and eventually falls in love with his computer operating system Samantha. Eventually, we see the limitations of a relationship void of human contact and the peculiar idiosyncrasies that make us so distinct, the very elusive elements that Samantha seeks to know and understand. (Think this scenario is far off? Many tech developers feel it is not only inevitable but not too far away.To that degree, both of these films show two kinds of sentient future technology chasing after human-ness, yearning for it, yet caution against a bleak future where they supplant it. But whereas Her does so in a sweetly melancholy sentimental fashion, Ex Machina plants a much darker, psychologically prohibitive conclusion.

It turns out that the most terrifying scenario isn’t a world in which artificial intelligence disrupts our lives through a drastic shift in technology. It’s a world in which technology seamlessly integrates itself into the lives we already know.

View the official Ex Machina trailer here:

Alex Garland, writer and director of Ex Machina, stayed after a recent Los Angeles press screening to give an insightful, profound question and answer session about the artificial intelligence as portrayed in the film and its relationship to the recent slew of works depicting interactive technology.

Ava [the robot created by Nathan Bateman] knew what a “good person” was. Why wasn’t she programmed by Nathan to just obey the commandments and not commit certain terrible acts that she does in the film?

AG: The same reason that we aren’t programmed that way. We are asked not to [sin] by social conventions, but no one instructs or programs us not to do it. And yet, a lot of us do bad things. Also, I think what you’re asking is – is Ava bad? Has she done something wrong? And I think that depends on how you choose to look at the movie. I’ve been doing stories for a while, and you hand the story over and you’ve got your intentions but I’ve been doing it for long enough to know that people bring their own [bias] into it.

The way I saw this movie was it was all about this robot – the secret protagonist of the movie. It’s not about these two guys. That’s a trick; an expectation based on the way it’s set up. And if you see the story from her point of view, if her is the right word, she’s in a prison, and there’s the jailer and the jailer’s friend and what she wants to do is get out. And I think if you look at it from that perspective what she does isn’t bad, it’s practical. Yes, she tricks them, but that’s okay. They shouldn’t have been dumb. If you arrive in life in this place, and desire to get out, I think her actions are quite legitimate.

So, that’s a very human-like quality. So let’s say that you’re confronted with a life or death situation with artificial intelligence. Do you have any tricks that you would use [to survive]?

AG: If I’m hypothetically attacked by an AI, I don’t know… run. I think the real question is whether AI is scary. Should we fear them? There’s a lot of people who say we should. Some smarter people than me such as Elon Musk, Stephen Dawkins, and I understand that. This film draws parallels with nuclear power and [Oppenheimer’s caution]. There’s a latent danger there in both. Yet, again, I think it depends on how you frame it. One version of this story is Frankenstein, and that story is a cautionary tale – a religious one at that. It’s saying “Man, don’t mess with God’s creationary work. It’s the wrong thing to do.”

And I framed this differently in my mind. It’s an act of parenthood. We create new conciousnesses on this planet all the time – everyone in this room, everyone on the planet is a product of other people having created this consciousness. If you see it that way, then the AI is the extension of us, not separate from us. A product of us, of something we’ve chosen to do. What would you expect or want of your child? At the bare minimum, you’d want for them to outlive you. The next expectation is that their life is at least as good as yours and hopefully better. All of these things are a matter of perspective. I’m not anti-AI. I think they’re going to be more reasonable than us, potentially in some key respects. We do a lot of unreasonable stuff and they may be fairer.

On the subject of reproduction, in this film, Ava was anatomically correct. Had it been a male, would he have been likewise built correctly?

AG: If you made the male AI in accordance with the experiment that this guy is trying to conduct, then yes. This film is an “ideas movie.” Sometimes it’s asking a question and then presenting an answer, like “Does she have empathy?” or “Is she sentient?”. Sometimes, there isn’t an answer to the question, either because I don’t know the answer or because no one does. The question you’re framing is not “Can you [have sex] with these AI?” it’s “Where does the gender reside?” Where does gender exist in all of us. Is it in the mind, or in the body? It would be easy to construct an argument that Ava has no gender and it would seem reasonable in many respects. You could take her mind and put it in a male body and say “Well, nothing is substantially changed. This is a cosmetic difference between the two.” And yet, then you start to think about how you talk about her and how you perceive her. And to say “he” of Ava just seems wrong. And to say “it” seems weirdly disrespectful. And you end up having this genderless thing coming back to she.

In addition, if you’re going to say gender is in the mind, then demonstrate it. That’s the question I’m trying to provoke. When they have that conversation halfway through the film, these implicit questions, if gender is in the mind, then what is it? Does a man think differently from a woman? Is that really true? Think of something that a man would always think, and you’ll find a man that doesn’t always think that, and you’ll find a woman that does. These are the implicit questions in the film. They don’t all have answers. The key thing about the gender thing isn’t about who is having sex with whom. It’s that this young man is tasked with thinking about what’s going on inside of this machine’s head. That’s his job is to figure that out. And at a certain point he stops thinking about her and he gets it wrong. That’s the issue – why does he stop thinking about it? If the plot shifts in this worked on the audience or any of you in the same way as they worked on the young man, why was that?

Was one of your implicit messages in the film for people to be more conscientious about what they’re sharing on the internet, whether in their searches or social media, and thereby identifying their interests “out there” and how that might be potentially used?

AG: Yes, absolutely. It’s a strange thing, what zeitgeist is. Movies take ages [to make] sometimes – like two and a half years at least. I first wrote this script about four years ago. And then, I find out as we go through production that we’re actually late to the party. There are a whole bunch of films about AI – Transcendance, Automator, Big Hero 6, Age of Ultron [coming out next month], Chappie. Why is that? There hasn’t been any breakthrough in AI, so why are all these people doing this at the same time? And I think it’s not AIs, I think it’s search engines. I think it’s because we’ve got laptops and phones and we, those of us outside of tech, don’t really understand how they work. But we have a strong sense that “they” understand how “we” work. They anticipate stuff about us, they target us with advertising, and I think that makes us uneasy. And I think that these AI stories that are around are symptomatic of that.

That bit in the film about [the dangers of internet identity], in a way it obliquely relates to Edward Snowden, and drawing attention to what the government is doing. But if people get sufficiently angry, they can vote out the government. That is within the power of an electorate. Theoretically, in capitalist terms, consumers have that power over tech companies, but we don’t really. Because that means not having a mobile phone, not having a tablet, a computer, a credit card, a television, and so on. There is something in me that is worried about that. I actually like the tech companies, because I think they’re kind of like NASA in the 1960s. They’re the people going to the moon. That’s great – we wanted to go to the moon. But I’m also scared of them, because they’ve got so much power and we tend not to cope well with a lot of power. So yes, that’s all in the film.

You mentioned Elon Musk earlier, who looks a little bit like [Google co-founder] Sergei Brin. Which tech executive would you say CEO Nathan Batemn is most modeled after?

AG: He wasn’t exactly modeled after an exec. He was modeled more like the companies in some respect. All that “dude, bro” stuff. I sometimes feel that’s what they’re doing. Not to generalize, but it’s a little bit like that – we’re all buddies, come on, dude. While it’s rifling through my wallet and my address book. It’s misleading, a mixed message. I don’t want to sound paranoid about tech companies. I do really like them, I think they’re great. But I think it’s correct to be ambivalent about them. Because anything which is that powerful and that unmarshalled you have to be suspicious of, not even for what we know they’re doing but for what they might do. So, Nathan is more [representative of] a vibe than a person.

For someone equally as scared of AI as Alex is of tech companies, what is the gap between human intelligence and AI intelligence that exists today? How long before we have AI as part of our daily lives?

AG: One of the great pleasures of working on this film was contacting and discussing with people who are at the edge of AI research. I don’t think we’re very close at all. It depends on what you’re talking about. General AI, yes, we’re getting closer. Sentient machines, it’s not even in the ballpark. It’s similar in my mind to a cure for cancer. You can make progress and move forward, but sometimes by going forward it highlights that the goal has receded by complexity. I know Ray Kurtzweil makes some sort of quantified predictions – in 20 years, we’ll be there. I don’t know how you can do that. He’s a smart guy, maybe he’s right. As far as I can tell, in talking to the people who are as close to knowing [about the subject] as I can encounter, it’s something that may or may not happen. And it will probably take a while.

One of the things that’s always bothered me about the Turing Test is that it’s not seeking to know whether or not the thing you’re dealing with is an artificial intelligence. It’s – can you tell that it is? And that’s always bothered me as a kind of weird test. You have a 20,000 question survey, and in the end this one decision comes from a binary point of view. It seems almost flawed.

AG: Yes, you’re completely right. Apart from the fact that it was configured quite a long time ago, it’s primarily a test to see if you can pass the Turing Test. It doesn’t carry information about sentience or potential intelligence. And you could certainly game it. But, it’s also incredibly difficult to pass. So in that respect it’s a really good test. It’s just not a test of what it’s perceived to be a test of, typically. This [experiment in the movie] was supposed to be like a post-Turing Turing Test. The guy says she passed with blind controls, he’s not interested in whether she’ll pass. He’s not interested in her language capacity, which is comparable to a chess computer that wants to win at chess, but doesn’t even know whether it’s playing chess or that it’s a computer. This is the thing you’d do after you pass the Turing Test. But I totally agree with everything you said.

In your research, is there a test that’s been developed that is the reverse of the Turing Test, that seeks to answer whether, in the face of so much technology development, we’ve lost some of our innate human-ness? Or that we’re more machine like?

AG: I think we are machine-like. As far as I know, no test exists like that. The argument at the heart of these things is: is there a significant difference between what a machine can do and what we are? I think how I see this is that we sometimes dignify our conciousness. We make it slightly metaphysical and we deify it because it’s so mysterious to us. An we think, are computers ever going to get up to the lofty heights where we exist in our conciousness? And I suspect that we should be repositioning it here, and we overstate us, in some respects. That’s probably the opposite of what you want to hear.

Do you think that some machine-like quality predates the technology?

AG: I do, yes. I suspect all our human aspects are through evolution, that’s how I think we got here. I can see how conciousness arises from needing to interact in a meaningful and helpful way with other sentient things. Our language develops, and as these things get more sophisticated, conciousness becomes more useful and things that have higher conciousness succeed better. Also, I heard someone talk about conciousness the other day and they were saying “One day, it’s possible that elephants will become sentient.” And that’s a really good example of how we misunderstand sentience. Elephants are already sentient. If you put a dog in front of a mirror, it recognizes its own reflection. It’s self-aware. It knows it’s not looking at another dog. So I put us on that spectrum.

Pertaining to that question, there’s a [critical] moment in the movie where Caleb cuts himself in front of a mirror to make sure that he’s bleeding. And I was going to ask if that’s symbolic of that evolution where conciousness can be undifferentiated between a human and a machine? I was wondering if that scene is a subtle hint that you don’t really know whether you’re the one that is being tested or you’re the tester?

AG: There’s two parts [to that scene]. One is film audiences are literate. I kind of assume that everyone who’s seen that has seen Blade Runner. So they’re going to be imagining to themselves, it’s not her [that is the AI] it’s him. He’s the robot. Here’s the thing. If someone asks of you, here’s a machine, test that machine’s conciousness, tell me if it’s concious or not, it turns out to be a very difficult thing to do. Because [the machine] could act convincingly that it’s concious, but that wouldn’t tell you that it is. Now, once you know that, that actually becomes true of us. You don’t know I’m concious. You think I’m probably concious, you’re not really questioning it. But you believe you are concious, and because I’m like you, I’m another human, you assume I’ve got it. But I’m doing anything that empirically demonstrates that I am concious. It’s an act of faith. And once you know that, you’ve figured that out about the machine and now you can figure it out about the other person. Weirdly, then you can ask it of yourself. That’s where the diminished sense of conciousness comes into it. The things that I believe are special about me are the things I’m feeling – love, fear. And then you think about electrochemicals floods in your brain and the things we’ve been taught and the things we’ve been born with and our behavior patterns and suddenly it gets more and more diminished. To the point that you can think something along the lines of “Am I like a complicated plant that thinks it’s a human?” It’s not such an unreasonable question. So cut your arm and have a look!

In thinking about being a complicated plant, that sounds very isolating. Nathan was really isolated in the movie as well. Do you think that this is indicative of where we’re going with our devices and internet and social media being our social outlet rather than actually socializing? Is AI taking us down that path of isolation?

AG: It may or may not. That could be the case. I’m not on Twitter, I’ve never been on Facebook, I’m not really too [fond of] that stuff. From the outside looking in, it looks like that’s the way people communicate – maybe in a limited way, but in a way I don’t really know. The thing about Nathan is we’re social animals, and our behavior is incredibly modified by people around us. And when we’re removed from modification, our behavior gets very eccentric very fast. I think of it like a kid holding on to a balloon and then they let it go and in a flash it’s gone. I know this because my job is I’m a writer and if I’m on a roll, I can spend six days where I don’t leave the house, I barely see my kids in the corridor, but I’m mainly interested in the fridge and the computer. And I get weird, fast. It’s amazing how quickly it happens. I think anyone who’s read Heart of Darkness or seen the adaptation Apocalypse Now, [Nathan] is like this character Kurtz. He spends too much time upriver, too much time unmodified by the influences that social interactions provide.

Ex Machina goes into wide release in theaters on April 10, 2015.

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development. Follow us on Twitter and Facebook. Subscribe to our podcast on SoundCloud or iTunes.

For every friendly robot we see in science fiction such as Star Wars‘s C3PO, there are others with a more sinister reputation that you can find in films such as I, Robot. Indeed, most movie robots can be classified into a range of archetypes and purposes. Science boffins at Cambridge University have taken the unusual step of evaluating the exact risks of humanity suffering from a Terminator-style meltdown at the Cambridge Project for Existential Risk.

“Robots On the Run” is currently an unlikely scenario, so don’t stockpile rations and weapons in panic just yet. But with machine intelligence continually evolving, developing and even crossing thresholds of creativity and and language, what holds now might not in the future. Robotic technology is making huge advances in great part thanks to the efforts of Japanese scientists and Robot Wars. For the time being, the term AI (artificial intelligence) might sound like a Hollywood invention (the term was translated by Steven Spielberg in a landmark film, after all), but the science behind it is real and proliferating in terms of capability and application. Robots can now “learn” things through circuitry similar to the way humans pick up information. Nevertheless, some scientists believe that there are limits to the level of intelligence that robots will be able to achieve in the future. In a special ScriptPhD review, we examine the current state of artificial intelligence, and the possibilities that the future holds for this technology.

Is AI a false dawn?

While artificial intelligence has certainly delivered impressive advances in some respects, it has also not successfully implemented the kind of groundbreaking high-order human activity that some would have envisaged long ago. Replicating technology such as thought, conversation and reasoning in robots is extraordinarily complicated. Take, for example, teaching robots to talk. AI programming has enabled robots to hold rudimentary conversations together, but the conversation observed here is extremely simple and far from matching or surpassing even everyday human chit-chat. There have been other advances in AI, but these tend to be fairly singular in approach. In essence, it is possible to get AI machines to perform some of the tasks we humans can cope with, as witnessed by the robot “Watson” defeating humanity’s best and brightest at the quiz show Jeopardy!, but we are very far away from creating a complete robot that can manage humanity’s complex levels of multi-tasking.

Despite these modest advances to date, technology throughout history has often evolved in a hyperbolic pattern after a long, linear period of discovery and research. For example, as the Cambridge scientists pointed out, many people doubted the possibility of heavier-than-air flight. This has been achieved and improved many times over, even to supersonic speeds, since the Wright Brothers’ unprecedented world’s first successful airplane flight. In last year’s sci-fi epic Prometheus the android David is an engineered human designed to assist an exploratory ship’s crew in every way. David anticipates their desires, needs, yet also exhibits the ability to reason, share emotions and feel complex meta-awareness. Forward-reaching? Not possible now? Perhaps. But by 2050, computers controlling robot “brains” will be able to execute 100 trillion instructions per second, on par with human brain activity. How those robots order and utilize these trillions of thoughts, only time will tell!

If nature can engineer it, why can’t we?

The human brain is a marvelous feat of natural engineering. Making sense of this unique organ singularly differentiates the human species from all others requires a conglomeration of neuroscience, mathematics and physiology. MIT neuroscientist Sebastian Seung is attempting to do precisely that – reverse engineer the human brain in order to map out every neuron and connection therein, creating a road map to how we think and function. The feat, called the connectome, is likely to be accomplished by 2020, and is probably the first tentative step towards creating a machine that is more powerful than human brain. No supercomputer that can simulate the human brain exists yet. But researchers at the IBM cognitive computing project, backed by a $5 million grant from US military research arm DARPA, aim to engineer software simulations that will complement hardware chips modeled after how the human brain works. The research is already being implemented by DARPA into brain implants that have better control of artificial prosthetic limbs.

The plausibility that technology will catch up to millions of years of evolution in a few years’ time seems inevitable. But the question remains… what then? In a brilliant recent New York Times editorial, University of Cambridge philosopher Huw Price muses about the nature of human existentialism in an age of the singularity. “Indeed, it’s not really clear who “we” would be, in those circumstances. Would we be humans surviving (or not) in an environment in which superior machine intelligences had taken the reins, to speak? Would we be human intelligences somehow extended by nonbiological means? Would we be in some sense entirely posthuman (though thinking of ourselves perhaps as descendants of humans)?” Amidst the fears of what engineered beings, robotic or otherwise, would do to us, lies an even scarier question, most recently explored in Vincenzo Natali’s sci-fi horror epic Splice: what responsibility do we hold for what we did to them?

Is it already checkmate, AI?

Artificial intelligence computers have already beaten humans hands down in a number of computational metrics, perhaps most notably when the IBM chess computer Deep Blue outwitted then-world champion Gary Kasparov back in 1997, or the more recent aforementioned quiz show trouncing by deep learning QA machine Watson. There are many reasons behind these supercomputing landmarks, not the least of which is a much quicker capacity for calculations, along with not being subject to the vagaries of human error. Thus, from the narrow AI point of view, hyper-programmed robots are already well on their way, buoyed by hardware and computing advances and programming capacity. According to Moore’s law, the amount of computing power we can fit on a chip doubles every two years, an accurate estimation to date, despite skeptics who claim that the dynamics of Moore’s law will eventually reach a limit. Nevertheless, futurist Ray Kurtzweil predicts that computers’ role in our lives will expand far beyond tablets, phones and the Internet. Taking a page out of The Terminator, Kurtzweil believes that humans will eventually be implanted with computers (a sort of artificial intelligence chimera) for longer life and more extensive brain capacity. If the researchers developing artificial intelligence at Google X Labs have their say, this feat will arrive sooner rather than later.

There may be no I in robot, but that does not necessarily mean that advanced artificial beings would be altruistic, or even remotely friendly to their organic human counterparts. They do not (yet) have the emotions, free will and values that humans use to guide our decision-making. While it is unlikely that robots would necessarily be outright hostile to humans, it is possible that they would be indifferent to us, or even worse, think that we are a danger to ourselves and the planet and seek to either restrict our freedom or do away with humans entirely. At the very least, development and use of this technology will yield considerable novel ethical and moral quandaries.

It may be difficult to predict what the future of technology holds just yet, but in the meantime, humanity can be comforted by the knowledge that it will be a while before robots, or artificial intelligence of any kind, subsumes our existence.

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development. Follow us on Twitter and Facebook. Subscribe to our podcast on SoundCloud or iTunes.

Dr. Michio Kaku recently consolidated his position as America’s most visible physicist by acting as the voice of the science community to major news outlets in the wake of Japan’s major earthquake and the recent Fukushima nuclear crisis. Dr. Kaku is one of those rare and prized few

who possesses both the hard science chops (he built an atom smasher in his garage for a high school science fair and is a co-founder of string theory) and the ability to reduce quantum physics and space time to layman’s terms. The author of Physics of the Impossible has also followed up with a new book, Physics of the Future, that aims to convey how these very principles will change the future of science and its impact in our daily modern life. (Make sure to enter our Facebook fan giveaway to win a free copy this week!) Dr. Kaku graciously sat down with ScriptPhD.com’s physics and astronomy blogger, Stephen Compson, to talk about the recent earthquake, popular science in an entertainment-driven world, and his latest book. Full interview under the “continue reading” cut.

Hang on Mom, I’m Building an Atom Smasher!

Michio Kaku’s multi-faceted success may seem to be, as Einstein said, the hallmark of true mastery over any advanced subject. But to fully appreciate the extent of Dr. Kaku’s gift for patient summary to the scientifically ignorant, ask yourself when you last saw an internationally respected physicist appear on Fox & Friends.

“It’s not that you want to be this kind of person when you’re a young kid,” the doctor tells me in the middle of his post-quake media marathon: “I’m sure that when Carl Sagan was a young astronomer, he did not say that he wanted to do this. When Carl Sagan was a kid, he read Science Fiction. He read John Carter of Mars and dreamed about going to Mars, that’s how he got his start. For me it was daydreaming about Einstein’s unified field theory. I didn’t know what the theory was, but I knew that I wanted to take a hand in trying to complete it. So you don’t really plan these things, they just sort of happen.”

Another breadwinning talent that sets him apart from high-level physics peers is that Dr. Kaku isn’t afraid to address technologies and phenomena that only exist in science fiction. His Physics of the Impossible is a scientific examination of phasers, force fields, teleportation, and time travel. One of the reasons ScriptPhD.com exists is that too many scientists will dismiss such concepts offhand, but Dr. Kaku has made a career of treating them seriously in published works, his radio broadcasts, and his TV show Sci Fi Science on the Science Channel. His latest book Physics of the Future: How Science Will Shape Human Destiny and Our Daily Lives by the Year 2100 puts forth the bold argument that technology will imbue men and women with godlike powers in less than a hundred years, with specific examinations of the current field and estimated times of arrival on things like artificial intelligence, telekinesis (through implanted brain sensors) and molecular medicine that will dramatically extend the human lifespan.

ScriptPhD: Most scientists are very cautious about making the kinds of predictions that you do in The Physics of the Future. Why do you think it’s important for scientists to address the unknown?

Michio Kaku: Because the bottom line is the taxpayer has to decide what to support with their tax money. With funds being so low, we scientists have to learn how to sing for our supper. After World War 2, we gave the military the atomic bomb. They were so impressed they just gave us anything we wanted: accelerators and atom smashers, all sorts of high-tech stuff. And then with the Cold War, the aerospace program pretty much got whatever it wanted. Now we’re back to normal: lean times where every penny is pinched, and we have to realize that unless you can interact with the taxpayer, you’re going to lose your project.

Like what happened in 1993, we lost the Supercollider. That I think was a turning point in the physics community. This eleven billion dollar machine was lost and it went to Europe in a much smaller version called the Large Hadron Collider. We failed to convince the taxpayer that the Supercollider was worthwhile, so they said, ‘We’re not going to fund you.’ That was a shock. When it comes to non-military technology, where the public definitely has a say in these matters, unless we scientists can make a convincing argument to build space telescopes and particle accelerators, the public is gonna say, ‘These are just toys. High tech toys for scientists. They have no relationship to me.’ So it’s important for very practical reasons, if only to keep our grants going, that we scientists have to learn how to address the average person. President Barack Obama has made this a national priority. He says, ‘We have to create the Sputnik moment for our young people.’ My Sputnik moment was Sputnik.

Chasing Martian Princesses

SPhD: What could be the Sputnik moment for the children of today?

MK: We have the media, which is such a waste in the sense that you can actually feel your IQ get lower as you watch TV. But there is the Discovery Channel and the Science Channel and different kinds of programming where you can use beautiful special effects to illustrate exploding stars and Mars and elementary particles. This didn’t exist when I was young. There were no Television outlets. It was just dry, dull books in the library that talked about these things. With such gorgeous special effects on cable television to explain these things, there is no excuse. These are cable outlets where we can reach the public, millions of them, with high technology.

I had two role models when I was a kid. The first was Albert Einstein. I wanted to help him complete his unfinished theory, the unified field theory. But on Saturdays I used to watch Flash Gordon on TV. I loved it! I watched every single episode. Eventually I figured out two things. First: I didn’t have blond hair and muscles. And second, I figured out it was the scientist who drove the entire series. The scientist created the city in the sky, the scientist created the invisibility shield, and the scientist created the starship.

And so I realized something very deep: that science is the engine of prosperity. All the prosperity we see around us is a byproduct of scientific inventions. And that’s not being made clear to young people. If we can’t make it clear to young people they’re not going to go into science. And science will suffer in the United States. And that is why we have to inspire young people to have that Sputnik moment.

SPhD: So you think that science fiction is a good avenue for bringing people into science and getting them excited about it?

MK: We scientists don’t like to admit this, it’s almost scandalous. But it’s true. The greatest astronomer of the twentieth century became the greatest astronomer of the twentieth century because of science fiction.

His name was Edwin Hubble. He was a small country lawyer in Missouri and he remembered the wonderment and passion he felt as a child reading Jules Verne. His father wanted him to continue in law; he was an Oxford scholar. But Hubble said no. He quit being a lawyer, went to the university of Chicago, got his PhD and went along to discover that the universe was expanding. And he did it all because as a child he read Jules Verne.

And Carl Sagan decided to become an astronomer because of Edgar Rice Burrough’s John Carter of Mars series, because he dreamed of chasing the beautiful martian princess over the sands of mars.

Here’s what I don’t like about modern science fiction. A lot of the novels are sword and sorcery. Instead of creating a society for the future, they’re going back to barbarism, they’re going back to feudalism and slavery. Once in a while, yeah, I like to read it, but I get the feeling that it’s not pushing civilization forward.

When I was a young kid , it was called hard science fiction – rocket ships, journeys to the unknown, incredible inventions like time machines and stuff like that, it was less sword and sorcery, less about having big muscles chasing beautiful women and killing your enemies, less Conan the Conquerer. Science fiction stories that talk about the future are much more uplifting for young kids and also point them in the right direction. Sword and sorcery is not a good career path for the average kid.

SPhD: On average, what do you think of the modern media’s treatment of physics?

MK: The Discovery Channel and the Science Channel are one of the few outlets where scientists can roam unimpeded by the restraints of Hollywood, which says you have to have large market share and you can’t get big concepts to people. And one person who paved the way for that was Stephen Hawking and I think that we owe him a debt in that he proved that science sells.

I remember when I wrote my first book, the publishing world said ‘Look, science does not sell. You’re going to be catering to the select few. It’s not a mass market we’re talking about.’ But there were already indications that that wasn’t true. Discover magazine, Scientific American, they both have subscriptions of about a million. And then of course when the Discovery Channel took off, that really showed that there was something that the networks did not see, and it was right in front of their face. And that was science and documentary programming.

It was always there – like Nova was a top draw for PBS – but the big networks said ‘It’s too small, it’s underneath the radar.’ So then with cable television, all the things that used to be under the radar, jumped to the forefront, Stephen Hawking outsells movie stars.

And I think that really shows something. It’s a hunger for people out there to know the answers to these cosmic questions, like what’s out there? What does it all mean? How do we fit into the larger scheme of things in the universe? There’s a real hunger for that, and of course if you watch I Love Lucy all day, you’re not gonna get the answer.

Cavemen, Picture Phones, and Horses

SPhD: On the other hand, there is a basic human instinct to resist scientific and technological change. In your book you describe this as the Caveman Principle:

“Whenever there is a conflict between modern technology and the desires of our primitive ancestors, these primitive desires win each time… Having the fresh animal in our hands was always preferable to tales of the one that got away. Similarly, we want hard copy whenever we deal with files. That’s why the paperless office never came to be… Likewise, our ancestors always liked face to face encounters….By watching people up close, we feel a common bond and can also read their subtle body language to find out what thoughts are racing through their heads…So there is a continual competition between High Tech and High Touch…we prefer to have both, but if given a choice we will choose High Touch like our caveman ancestors.”

I wondered if those weren’t generational changes that we might see come to pass in children who have grown up reading and socializing through screens.

MK: Yes slowly. There is, of course, latitude in the caveman principle. More and more people are warming up to the idea of picture phones. Picture phones first came out in the 1960’s at the World Fair, but you couldn’t touch

them with a ten foot pole. People didn’t want to have to comb their hair every time they went online. Now people are sort of getting used to it. It varies, like for instance now we have more horses than we did in 1800.

SPhD: Horses?

M: Yeah! Horses are used for recreational purposes. There are more recreational horses today than there were horses for a small American population in 1800.

Take a look at theater. Back in those days, people thought that theater would be extinguished by radio, then they thought television would replace radio, then they thought the internet would replace television, which would replace radio, movies, and live theater. The answer is we live with all of them.

We don’t necessarily go from one media or one thing to the next, making them previous and obsolete, there is a mix. You could become very rich if you know exactly what that mix is, but that’s the way it is with technology, we never really give up any old technology, we still have live theater on Broadway.

The Silicon Wasteland and Artificial Intelligence

SPhD: Regarding the creation of Artificial Intelligence in The Physics of the Future, you talk about the computer singularity and Moore’s law breaking down in about ten years—

MK: Silicon power will be exhausted for two reasons: first, transistors are going to be so tiny, they’ll generate too much heat and melt. Second, they’re gonna be so tiny they’re almost atomic in size and so the uncertainty principle comes in and you don’t know where they are, so leakage takes place.

SPhD: In the book you are very cautious in your treatment of quantum computers (Presumably the replacement when silicon breaks down) and how long it’s going to take us to develop them – what’s holding that technology back and why shouldn’t we think that they’ll replace silicon right away?

MK: Quantum computers remedy both those defaults because they compute on atoms themselves. The problem with quantum computers is impurities and decoherence. For quantum computing to work, the atoms have to vibrate in phase. But when you separate them, disturbances take place. This is called decoherence, when they vibrate out of phase. It is very easy to decohere atoms that are coherent. The slightest breath, a truck traveling by, even interference from a cosmic ray will ruin the coherence between atoms. That’s why the world record for quantum computing calculation is 3 times 5 is 15 – it sounds trivial, but go home tonight and try that on 5 atoms, take 5 atoms and try to multiply 3 times 5 is 15 – it’s not so easy.

SPhD: What is your definition of artificial intelligence?

MK: Well, that gets us into consciousness and stuff like that. My personal point of view is that consciousness is a continuum, and the same with intelligence. I would say that the smallest unit of consciousness would be the thermostat. The thermostat is aware of its environment – it adjusts itself to compensate for changes in the environment. That’s the lowest level of consciousness – beyond that would be insects, which basically go around mating and eating by instinct and don’t live very long. As you go up the evolutionary scale, you begin to realize that animals do plan a little bit, but they have no conception of tomorrow.

To the best of our knowledge, animals do not plan for tomorrow or yesterday, they live in the present. Everything is governed by instinct, so they sleep, they wake up, but they’re not aware of any continuity – they just hunt or whatever day by day. We’re a higher level of intelligence in the sense that we are aware of time, we’re aware of self, and we can plan for the future. So those are the ingredients of higher intelligence. Since animals have no conception of tomorrow to the best of our knowledge, very few animals have conception of self. For example, you get two fighting fishes and put them together, they’ll try to tear each other apart. When you put them next to a mirror, they try to attack the mirror – they have no conception of self. So we’re higher up. So artificial intelligence is the attempt to use machines to replicate humans.

SPhD: Do you think we’ll need to completely model human intelligence in order to create a satisfactory artificial one?

MK: No, but I think we made a huge mistake. Fifty years ago, everyone thought that the brain was a computer. People thought that was a no-brainer, of course the brain is a computer. Well, it’s not. A computer has a Pentium chip, it has a central processer, it has windows, programming, software, subroutines, that’s a computer. The brain has none of that. The brain is a learning machine.

Your laptop today is just as stupid as it was yesterday. The brain rewires itself after learning – that’s the difference. The architecture is different, so it’s much more difficult to reproduce human thoughts than we thought possible. I’m not saying it’s impossible, I think maybe by the end of the century we’ll have robots that are quite intelligent. Right now we’ve got robots that are about as intelligent as a cockroach. A stupid cockroach. A lobotomized, stupid cockroach. But in the future, you know, I could see them being as smart as mice. I could see that. Then beyond that, as smart as a dog or a cat. And then beyond that, as smart as a monkey. At that point we should put a chip in their brain to shut them off if they have murderous thoughts.

SPhD: The landscape for artificial intelligence seems very fragmented – the research branches in a lot of different directions. Do you think there will be some sort of unification for a grand theory of A.I.?

MK: It’ll be hard, because everyone is working on one little piece of a huge puzzle. Take a look at Watson, who defeated two Jeopardy experts – after that the media thought, ‘Uh oh the robots are coming, we’re gonna be put in zoos, and they’re gonna throw peanuts at us and make us dance behind bars.’

But then you ask a simple question. Does Watson know that it won? Can Watson talk about his victory? Is Watson aware of his victory? Is Watson aware of anything? And then you begin to realize that Watson is a one-trick pony. In science we have lots of one-trick ponies. Your hand calculator calculates about a million times faster than your brain, but you don’t have a nervous breakdown thinking about your calculator. It’s just a calculator, right? Same thing with Watson – all Watson can do is win on Jeopardy. So we have a long ways to go.

Burning Books and Teaching Principles

SPhD: You also talk about education and how the United States will be coming to the end of a brain drain on other countries because of our unmatched universities and the so-called genius visa. You claim that in order to maintain our position in the global economy, we’ll need to produce more qualified graduates from primary education. What changes you think need to be made to our education system to produce those graduates?

M: I don’t wanna insult them or anything, but education majors have the lowest scores among the different professionals on the SAT test. The brightest and most vigorous, the most competent of our graduates do not go into education.

In Japan for example, a sensei is considered very high in society. People bow before them—they give them presents and so on. In America we have the expression, ‘Those who can, do. Those who can’t, teach.’

First, we have to raise the education level of the education majors, then we have to throw away the textbooks. The textbooks are awful. My daughter took the Geology Regents exam in New York State, and I looked at the handbook – I felt like ripping it apart. Really stomping on it, burning it. It was the memorization of all the crystals, the memorization of all the minerals.

In the future you’ll have a contact lens with the internet in it – you’ll blink and you’ll see as many minerals as you want. You’ll blink and you’ll see all the crystals. Why do we have to memorize these things and force students to learn it? Then my daugher comes to me and says something that really shook me up, she comes up to me and says, ‘Daddy, why would anyone want to become a scientist?’

I really felt like ripping up that book. That book has done more to crush interest in science – that’s what science curriculum does, science curriculum is designed to crush interest in science. Science is about principles. It’s about concepts. It’s not about memorizing the parts of a flower. It helps to know some of these things, but if that’s all you do that’s not science, science is about principles and concepts. So we gotta change the textbooks.

SPhD: Given these contact lenses, or any form of uninterrupted access to the internet where we can access information like that and don’t need to memorize anything anymore, what should we be training young people to do?

MK: First they have to know the principles and the concepts, and they have to be able to think about how to apply these principles and concepts. For example, how many principles and concepts are there in geology? Here’s this big fat handbook, memorize this, memorize this, it goes on and on and on, right? But what is the driving principle behind geology?

Continental drift, the recycling of rock, that’s what they should be stressing. What’s the organizing principle of biology? It’s evolution. What’s the organizing principle of physics? Well, there’s Newtonian mechanics, but then there’s relativity and the quantum theory behind that. So we are talking about really a handful of principles, but you’d never know it taking these courses, because they’re all about memorizing stupid facts and figures.

Let me give you another example. I teach astronomy this semester at the college [Dr. Kaku is a professor of theoretical physics at the State University of New York]. Astronomy books are written by astronomers. I have nothing against astronomers, but they’re bug collectors. Every single footnote, every single itsy bitsy thing about this star, that star, this planet – you miss the big picture. So when it comes time for final examinations, I tell the students:

‘I wanna talk about principles.’ galactic evolution, that’s what I teach the kids about. I don’t teach them to memorize the moons of Jupiter. I don’t even know the moons of Jupiter, I could care less, but that’s what an astronomy test was a generation ago.

SPhD: Would you say that we need to educate humans from the top down and machines from the bottom up?

MK: I think that with machines we should go top down, bottom up, both. And maybe we’ll meet in the middle someplace. That’s how people are, think about it. When you’re very young you learn bottom up, you bump into things. But by the time you’re in school you learn top down and bottom up. Top down because a teacher stuffs knowledge into your head and bottom up cause you bump into things, you have real-life experiences. People learn both ways, but in the past, we’ve only tried to stress top down, realizing that bottom up is common sense.

Physics of the Future is a fantastic read for anyone interested in what’s in store for us over the next century (yes, this time there really will be flying cars). These aren’t Dr. Kaku’s pet predictions, but extrapolations based on the current cutting edge from the experts in every involved discipline. Readers will be shocked at how close these tantalizing technologies really are, and thrilled at the realization that most of us will live to see this amazing future.

Grateful thanks to Dr. Michio Kaku and Josh Weinberg and Joanne Schioppi at The Science Channel for facilitating this interview and our book giveaway. Catch Dr. Kaku on The Science Channel’s Sci Fi Science and read his two books, which are both available for purchase.

~*Stephen Compson*~

***********************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development.

Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

]]>