Ray Bradbury, one of the most influential and prolific science fiction writers of all time, has had a lasting impact on a broad array of entertainment culture. In his canon of books, Bradbury often emphasized exploring human psychology to create tension in his stories, which left the more fantastical elements lurking just below the surface. Many of his works have been adapted for movies, comic books, television, and the stage, and the themes he explores continue to resonate with audiences today. The notable 1966 classic film Fahrenheit 451 perfectly captured the definition of a futuristic dystopia, for example, while the eponymous television series he penned, The Ray Bradbury Theatre, is an anthology of science fiction stories and teleplays whose themes greatly represented Bradbury’s signature style. ScriptPhD.com was privileged to cover one of Ray Bradbury’s last appearances at San Diego Comic-Con, just prior to his death, where he discussed everything from his disdain for the Internet to his prescient premonitions of many technological advances to his steadfast support for the necessity of space exploration. In the special guest post below, we explore how the latest Bradbury adapataion, the new television show The Whispers, continues his enduring legacy of psychological and sci-fi suspense.

Premiering to largely positive reviews, ABC’s new show The Whispers is based on Bradbury’s short story “Zero Hour” from his book The Illustrated Man. Both stories are about children finding a new imaginary friend, Drill, who wants to play a game called “Invasion” with them. The adults in their lives are dismissive of their behavior until the children start acting strangely and sinister events start to take place. Bradbury’s story is a relatively short read with just a few characters that ends on a chilling note, while The Whispers seeks to extend the plot over the course of at least one season, and to that end it features an expanded cast including journalists, policemen, and government agents.

The targeting of young, impressionable minds by malevolent forces is deeply disturbing, and it seems entirely plausible that parents would write off odd behavior or the presence of imaginary friends as a simple part of growing up. In both the story and the show, the adults do not realize that they are dealing with a very real and tangible threat until it’s too late. The dread escalates when the adults realize that children who don’t know each other are all talking to the same person. The fear of the unknown, merely hinted at in Bradbury’s story, will seem to be exploited to great effect during the show’s run.

When “Zero Hour” was written in 1951, America was in the midst of McCarthyism and the Red Scare, and the fear of Communism and homosexuality ran rampant. As the tensions of the Cold War grew, so too did the anxiety that Communists had infiltrated American society, with many of the most aggressively targeted individuals for “un-American” activities belonging to the Hollywood filmmaking and writing communities. Bradbury’s story shares with many other fictions of the time period a healthy dose of paranoia and fear around possession and mind control. Indeed, Fahrenheit 451, a parable about a futuristic world in which books are banned, is also a parable about the dangers of censorship and political hysteria.

The makers of The Whispers recognize that these concerns still permeate our collective consciousness, and have updated the story with modern subject matter, expanding the subject of our apprehension to state surveillance and abuse of authority. To wit, many recent films and shows have explored similar themes amidst the psychological ramifications of highly developed artificial intelligence and its ability to control and even harm humans. Our concurrent obsession with and fear of technology run amok is another topic explored by Ray Bradbury in many of his later works. The idea that those around us are participating in a grand scheme that will bring us harm still sows seeds of discontent and mistrust in our minds. For that reason, the concept continues to be used in suspense television and cinema to this day.

One of the reasons Bradbury’s work continues to serve as the inspiration for so much contemporary entertainment is his use of everyday situations and human oddities to create intrigue. One such example is a 5-issue series called Shadow Show based on Bradbury’s work, released in 2014 by comic book publisher IDW. Some of the best artists, writers and comics had agreed to participate in this project since Bradbury had such a huge influence in their writing and art. In this anthology, Harlan Ellison’s “Weariness” perfectly elicits Bradbury’s dystopia in which our main characters experience the universe’s end. The terrifying end of life as we know it is one of Bradbury’s recurring themes, depicted in writings like The Martian Chronicles. He rarely felt the need to set his stories in faraway galaxies or adorn them with futuristic gadgets. Most of his writing focussed on the frightening aspects of humans in quotidien surroundings, such as in the 2002 novel, Let’s All Kill Constance. Much of The Whispers takes place in an ordinary suburban neighborhood, and like many of his stories, what seems at first to be a simple curiosity, is hiding something much more complex and frightening.

Fiction that brings out the spookiness inherent in so many facets of human nature creates a stronger and more enduring bond with its audience, since we can easily deposit ourselves into the characters’ situations, and all of a sudden we find that we’re directly experiencing their plight on an emotional level. That’s always been, as Bradbury well knew, the key to great suspense.

Maria Ramos is a tech and sci-fi writer interested in comic books, cycling, and horror films. Her hobbies include cooking, doodling, and finding local shops around the city. She currently lives in Chicago with her two pet turtles, Franklin and Roy. You can follow her on Twitter @MariaRamos1889.

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development. Follow us on Twitter and Facebook. Subscribe to our podcast on SoundCloud or iTunes.

This past weekend, over 130,000 people descended on the San Diego Convention Center to take part in Comic-Con 2012. Each year, a growing amalgamation of costumed super heroes, comics geeks, sci-fi enthusiasts and die-hard fans of more mainstream entertainment pop culture mix together to celebrate and share the popular arts. Some are there to observe, some to find future employment and others to do business, as beautifully depicted in this year’s Morgan Spurlock documentary Comic-Con Episode IV: A Fan’s Hope. But Comic-Con San Diego is more than just a convention or a pop culture phenomenon. It is a symbol of the big business that comics and transmedia pop culture has become. It is a harbinger of future profits in the entertainment industry, which often uses Comic-Con to gauge buzz about releases and spot emerging trends. And it is also a cautionary tale for anyone working at the intersection of television, film, video games and publishing about the meteoric rise of an industry and the uncertainty of where it goes next. We review Rob Salkowitz’s new book Comic-Con and the Business of Pop Culture, an engaging insider perspective on the convergence of geekdom and big business.

Comic-Con wasn’t always the packed, “see and be seen” cultural juggernaut it’s become, as Salkowitz details in the early chapters of his book. In fact, 43 years ago, when the first Con was held at the US Grant hotel in San Diego, led by the efforts of comics superfan Shel Dorf, only 300 people came! In its early days, Comic-Con was a casual place where the titans of comics publishers such as DC and Marvel would gather with fans and other semi-professional artists to exchange ideas and critique one another’s work in an intimate setting. In fact, Salkowitz, a long-time Con attendee who has garnered quite a few insider perks along the way over the years, recalls that his early days of attendance were not quite so harried and frantic. The audience for Comic-Con steadily grew until about 2000, when attendance began skyrocketing, to the point that it now takes over an entire American city for a week each year. Why did this happen? Salkowitz argues that this time period is when a quantum leap shift occurred away from comic books and towards comics culture, a platform that transcends graphic novels and traditional comic books and usurps the entertainment and business matrices of television, film, video games and other “mainstream” art. Indeed, when ScriptPhD last covered Comic-Con in 2010, even their slogan changed to “celebrating the popular arts,” a seismic shift in focus and attention. (This year, Con organizers made explicit attempts to explore the history and heritage partially in order to assuage purists who argue that the event has lost sight of its roots.) In theory, this meteoric rise is wonderful, right? With all that money flowing, everyone wins! Not so fast.

Lost amidst the pomp and circumstance of the yearly festivities is the fact that within this mixed array of cultural forces, there are cracks in the armor. For one thing, comics themselves are not doing well at all. For example, more than 70 million people bought a ticket to the 2008 movie The Dark Knight, but fewer than 70,000 people bought the July 2011 issue of Batman: The Dark Knight. Salkowitz postulates that we may be nearing the unimaginable: a “future of the comics industry that does not include comic books.” To unravel the backstory behind the upstaging of an industry at its own event, Salkowitz structures the book around the four days of the 2011 San Diego Comic-Con. In a rather clever bit of exposition, he weaves between four days of events, meetings, exclusive parties, panels of various size and one-on-one interactions to take the reader on a guided tour of Comic-Con, while in the process peeling back the layers of transmedia and business collaborations

that are the underbelly of the current “peak geek” saturation. A brief divergence to the downfall of the traditional publishing industry, including bookstores (the traditional sellers of comics), the reliance of comics on movie adaptations and the pitfalls of digital publication is a must-read primer for anyone wishing to work in the industry. Even more strapped are merchants that sell rare comics and collectibles on the convention floor. Often relegated to the side corners with famous comics artists so that entertainment conglomerates can occupy prime real estate on the floor, many dealers struggle just to break even. Among them are independent comics, self-published artists, and “alternative” comics, all hoping to cash in on the Comic-Con sweepstakes. Comics may be big business, but not for everyone. Forays into the world of grass-roots publishing, the microcosm of the yearly Eisner Awards for achievement in comics and the alternative con within a Con called Trickster (a more low-key networking event that harkens to the days of yore) all remind the reader of the tight-knit relationship that comics have with their fan base.

In many ways, the comics crisis that Salkowitz describes is not only very real, but difficult to resolve. The erosion of print media is unlikely to be reversed, nor is the penchant towards acquiring free content in the digital universe. Furthermore, video games, represent one of the biggest single-cause reasons for the erosion of comics in the last 20 years. Games such as Halo, Mass Effect, Grand Theft Auto and others, execute recurring linear storylines in a more cost-conscious three-dimensional interactive platform. On the other hand, there are also a myriad of reasons to be positive about the future of comics. The advent of tablets (notably the iPad) represents an unprecedented opportunity to re-establish comics’ popularity and distribution profits. Traditional and casual fans of comics haven’t gone anywhere, they’re just temporarily drowned out by the lines for the Twilight panel. A rising demographic of geek girls represents a potential growth segment in audience. And finally, a tremendous rise in popularity of traditional comics (even the classics) in global markets such as India and China portends a new global model for marketing and distribution. If superheroes are to continue as the mainstay of live-action media, the entertainment industry is highly dependent upon a viable, continued production of good stories. Movies need for comics to stay robust. The creativity and ingenuity that has been the hallmark of great comics continues to thrive with independent artists, some of whose work has gone viral and garnered publishing contracts.

Make no mistake, comics fans and enthusiastic geeks. Comic-Con and the Business of Pop Culture is very much a business and brand strategy book, centered around a very trendy and chic brand. There’s no question that casual fans and people interested in the more technical side of comics transmedia will find it an interesting, if at times esoteric, read. But for those working in (or aspiring to) the intersection of comics and entertainment, it is an essential read. Cautioning both the entertainment and comics industries against complacency against what could be a temporary “gold rush” cultural phenomenon, Salkowitz nevertheless peppers the book with salient advice for sustaining comics-based entertainment and media, while fortifying traditional comics and their creative integrity for the next generation of fans. The final portion of the book is its strongest; a hypothetical journey several years into the future, utilizing what he calls “scenario planning” to prognosticate what might happen. Comic-Con (and all the business that it represents) might grow larger than ever, an absolute phenomenon, might scale back to account for a diminishing fan interest, might stay the same or fraction into a series of global events to account for the growing overseas interest in traditional comics. Which one will come to fruition depends on brand synergy, fan growth and engagement, distribution with digital and interactive media, and a carefully cultivated relationship between comics audiences, creators and publishers. Salkowitz calls Comic-Con a “laboratory in which the global future of media is unspooling in real time.” What will happen next? Like any good scientist knows, experiments, even under controlled circumstances, are entirely unpredictable. See you in San Diego next year!

Rob Salkowitz is the cofounder and Principal Consultant of Seattle-based MediaPlant LLC and is the author of two other books, Young World Rising and Generation Blend. He also teaches in the Digital Media program at the University of Washington. Follow Rob on Twitter.

~*ScriptPhD*~

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development.

Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

]]>

Read through any archive of science fiction movies, and you quickly realize that the merger of pop culture and science dates as far back as the dawn of cinema in the early 1920s. Even more surprising than the enduring prevalence of science in film is that the relationship between film directors, scribes and the science advisors that have influenced their works is equally as rich and timeless. Lab Coats in Hollywood: Science, Scientists, and Cinema (2011, MIT Press), one of the most in-depth books on the intersection of science and Hollywood to date, serves as the backdrop for recounting the history of science and technology in film, how it influenced real-world research and the scientists that contributed their ideas to improve the cinematic realism of science and scientists. For a full ScriptPhD.com review and in-depth extended discussion of science advising in the film industry, please click the “continue reading” cut.

Written by David A. Kirby, Lecturer in Science Communication Studies at the Centre for History of Science, Technology and Medicine at the University of Manchester, England, Lab Coats offers a surprising, detailed analysis of the symbiotic—if sometimes contentious—partnership between filmmakers and scientists. This includes the wide-ranging services science advisors can be asked to provide to members of a film’s production staff, how these ideas are subsequently incorporated into the film, and why the depiction of scientists in film carries such enormous real-world consequences. Thorough, detailed, and honest, Lab Coats in Hollywood is an exhaustive tome of the history of scientists’ impact on cinema and storytelling. It’s also an essential and realistic road map of the challenges that scientists, engineers and other technical advisors might face as they seriously pursue science advising to the film industry as a career.

The essential questions that Lab Coats in Hollywood addresses are these—is it worth it to hire a science advisor for a movie production? Is it worth it for the scientist to be an advisor? The book’s purposefully vague conclusion is that it depends solely on how the scientist can film’s storyline and visual effects. Kirby wisely writes with an objective tone here because the topic is open to a considerable amount of debate among the scientists and filmmakers profiled in the book. Sometimes a scientist is so key to a film’s development, he or she becomes an indispensible part of the day-to-day production. A good example of this is Jack Horner, paleontologist at the Museum of the Rockies in Bozeman, MT, and technical science advisor to Steven Spielberg in Jurassic Park and both of its sequels. Horner, who drew from his own research on the link between dinosaurs and birds for a more realistic depiction of the film’s contentious science, helped filmmakers construct visuals, write dialogue, character reactions, animal behaviors, and map out entire scenes. J. Marvin Herndon, a geophysicist at the Transdyne Corporation, approached the director of the disaster film The Core when he learned the plot was going to be based on his controversial hypothesis about a giant uranium ball in the center of the Earth. Herndon’s ideas were fully incorporated into the film’s plot, while Herndon rode the wave of publicity from the film to publish his research in a PNAS paper. The gold standard of science input, however, were Stanley Kubrik’s multiple science and engineering advisors for 2001: A Space Odyssey, discussed in much further detail below.

Kirby hypothesizes that sometimes, a film’s poor reception might have been avoided with a science advisor. He provides the example of the Arnold Schwarzenegger futuristic sci-fi bomb The Sixth Day, which contained a ludicrously implausible use of human cloning in its main plot. While the film may have been destined for failure, Kirby posits that it only could have benefited from proper script vetting by a scientist. By contrast, the 1998 action adventure thriller Armageddon came under heavy expert criticism for its basic assertion that an asteroid “the size of Texas” could go undetected until eighteen days before impact. Director Michael Bay patently refused to take the advice of his advisor, NASA researcher Ivan Bakey, and admitted he was sacrificing science for plot, but Armageddon went on to be a huge box office hit regardless. Quite often, the presence of a science advisor is helpful, albeit unnecessary. One of the book’s more amusing anecdotes is about Dustin Hoffman’s hyper-obsessive shadowing of a scientist for the making of the pandemic thriller Outbreak (great guide to the movie’s science can be found here). Hoffman was preparing to play a virologist and wanted to infuse realism in all of his character’s reactions. Hoffman kept asking the scientist to document reactions in mundane situations that we all encounter—a traffic jam, for example—only to come to the shocking conclusion that the scientist was a real person just like everyone else.

Most of the time, including scientists in the filmmaking process is at the discretion of the studios because of the one immutable decree reiterated throughout the book: the story is king. When a writer, producer or director hires a science consultant, their expertise is utilized solely to facilitate, improve or augment story elements for the purposes of entertaining the audience. Because of this, one of the most difficult adjustments a science consultant may face is a secondary status on-set even though they may be a superstar in their own field. Some of the other less glamorous aspects of film consulting include heavy negotiations with unionized writers for script or storyline changes, long working hours, a delicate balance between side consulting work and a day job, and most importantly, an inconsistent (sometimes nonexistent) payment structure per project. I was notably thrilled to see Kirby mention the pros and cons of programs such as the National Science Foundation’s Creative Science Studio (a collaboration with USC’s school of the Cinematic Arts) and the National Academy of Science’s Science and Entertainment Exchange, which both provide on-demand scientific expertise to the Hollywood filmmaking community in the hope of increasing and promoting the realism of scientific portrayal in film. While valuable commodities to science communication, both programs have had the unfortunate effect of acclimating Hollywood studios to expect high-level scientific consulting for free.

1968’s 2001: A Space Odyssey is widely considered by popular consensus to be the greatest sci-fi movie ever made, and certainly the most influential. As such, Kirby devotes an entire chapter to detailing the film’s production and integration of science. Director Stanley Kubrik took painstaking detail in scientific accuracy to explore complex ideas about the relationship between humanity and technology, hiring a range of advisors from anthropologists, aeronautical engineers, statisticians, and nuclear physicists for various stages of production. Statistician I. J. Good provided advice on supercomputers, aerospace Harry Lange provided production design, while NASA space scientist Frederick Ordway lent over three years of his time to develop the space technology used in the film. In doing so, Kubrik’s staff consulted with over sixty-five different private companies, government agencies, university groups and research institutions. So real was the space technology in 2001 that moon landing hoax supporters have claimed the real moon landing by United States astronauts, taking place in 1969, was taped on the same sets. Not every science-based film has used science input as meticulously or thoroughly since, but Kubrik’s influence on the film industry’s fascination with science and technology has been an undeniable legacy.

One of the real treats of Lab Coats in Hollywood is the exploration of the two-way relationship between scientists and filmmakers, and how film in turn influences the course of science, as we discuss in more detail below. Between film case studies, critiques and interviews with past science advisors are interstitial vignettes of ways scientists have shaped films we know and love. Even the animated feature Finding Nemo had an oceanography advisor to get the marine biology correct. The seminal moment of the most recent Star Trek installation was due to a piece of off-handed scientific advice from an astronomer. The cloning science of Jurassic Park, so thoroughly researched and pieced together by director Steven Spielberg and science advisor Jack Horner, was actually published in a top-notch journal days ahead of the movie’s premiere. Even in rare spots where the book drags a bit with highly technical analysis are cinematic backstories with details that readers will salivate over. (For example, there’s a very good reason all the kelp went missing from Finding Nemo between its cinematic and DVD releases.)

As the director of a creative scientific consulting company based in Los Angeles, one of the biggest questions I get asked on a regular basis is “What does a science advisor do, exactly?” Lab Coats in Hollywood does an excellent job of recounting stories and case studies of high-profile scientist consultants, all of whom contributed their creative talents to their respective films in different ways, what might be expected (and not expected) of scientists on set, and of giving different areas of expertise that are currently in demand in Hollywood. Kirby breaks down cinematic fact checking, the most frequent task scientists are hired to perform, into three areas within textbook science (known, proven facts that cannot be disputed, such as gravity): public science, something we all know and would think was ridiculous if filmmakers got wrong, expert science, facts that are known to specialists and scientific experts outside of the lay audience, and (most problematic) folk science, incorrect science that has nevertheless been accepted as true by the public. Filmmakers are most likely to alter or modify facts that they perceive as expert science to minimize repercussions at the box office.

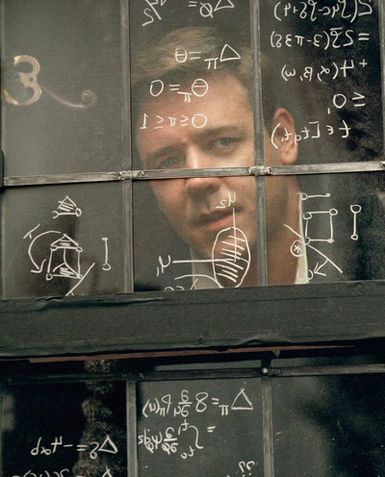

A science advisor is constantly navigating cinematic storytelling constraints and a filmmaker’s desire to utilize only the most visually appealing and interesting aspects of science (regardless of whether the context is always academically appropriate). Another broad area of high demand is in helping actors look and act like a real scientist on screen. Scientists have been hired to do everything from doctoring dialogue to add realism into an actor’s portrayal (the movie Contact and Jodie Foster’s depiction of Dr. Ellie Arroway is a good example of this), training actors in using equipment and pronouncing foreign-sounding jargon, replicating laboratory notebooks or chalkboard scribbles with the symbols and shorthand of science (such as in the mathematics film A Beautiful Mind), and to recreate the physical space of an authentic laboratory. Finally, the scientist’s expertise of the known is used to help construct plausible scenarios and storylines for the speculative, an area that requires the greatest degree of flexibility and compromise from the science advisor. Uncertainty, unexplored research and “what if” scenarios, the bane of every scientist’s existence, happen to be Hollywood’s favorite scenarios, because they allow the greatest creative freedom in storytelling and speculative conceptualization without being negated by a proven scientific impossibility. An entire chapter—the book’s finest—is devoted to two case studies, Deep Impact and The Hulk, where real science concepts (near-Earth asteroid impacts and genetic engineering, respectively) were researched and integrated into the stories that unfolded in the films. (Side note: if you are ever planning on being a science advisor read this section of the book very carefully).

In years past, consulting in films didn’t necessarily bring acclaim to scientists within their own research communities; indeed, Lab Coats recounts many instances where scientists were viewed as betraying science or undermining its seriousness with Hollywood frivolity, including many popular media figures such as Carl Sagan and Paul Ehrlich. Recently, however, consultants have come to be viewed as publicity investments both by studios that hire high-profile researchers for recognition value of their film’s science content and by institutes that benefit from branding and exposure. Science films from the last 10-15 years such as GATTACA, Outbreak, Armageddon, Contact, The Day After Tomorrow and a panoply of space-related flicks have attached big-name scientists as consultants (gene therapy pioneer French Anderson, epidemiologist David Morens, NASA director Ivan Bekey, SETI institute astronomers Seth Shostak and Jill Tartar and climatologist Michael Molitor, respectively). They also happened to revolve around the research salient to our modern era: genetic bioengineering, global infectious diseases, near-earth objects, global warming and (as always) exploring deep space. As such, a mutually beneficial marketing relationship has emerged between science advisors and studios that transcends the film itself resulting in funding and visibility to individual scientists, their research, and even institutes and research centers. The National Severe Storms Laboratory (NSSL) promoted themselves in two recent films, Twister and Dante’s Peak, using the films as a vehicle to promote their scientific work, to brand themselves as heroes underfunded by the government, and to temper public expectations about storm predictions. No institute has had a deeper relationship with Hollywood than NASA, extending back to the Star Trek television series, with intricate involvement and prominent logo display in the films Apollo 13, Armageddon, Mission to Mars, and Space Cowboys. Some critics have argued that this relationship played an integral role in helping NASA maintain a positive public profile after the devastating 1986 Challenger space shuttle disaster. The end result of the aforementioned promotion via cinematic integration can only benefit scientific innovation and public support.

Accurate and favorable portrayal of science content in modern cinema has an even bigger beneficiary than specific research institutes, and that is society itself. Fictional technology portrayed in film – termed a “diegetic prototype” – has often inspired or led directly to real-world application and development. Kirby offers the most impactful case of diegetic prototyping as the 1981 film Threshold, which portrayed the first successful implantation of a permanent artificial heart, a medical marvel that became reality only a year later. Robert Jarvik, inventor of the Jarvik-7 artificial heart used in the transplant, was also a key medical advisor for Threshold, and felt that his participation in the film could both facilitate technological realism and by doing so, help ease public fears about what was then considered a freak surgery, even engendering a ban in Great Britain. Of the many obstacles that expensive, ambitious, large-scale research faces, Kirby argues that skepticism or lack of enthusiasm from the public can be the most difficult to overcome, precisely because it feeds directly into essential political support that makes funding possible. A later example of film as an avenue for promotion of futuristic technology is Minority Report, set in the year 2054, and featuring realistic gestural interfacing technology and visual analytics software used to predict crime before it actually happens. Less than a decade later, technology and gadgets featured in the film have come to fruition in the form of multi-touch interfaces like the iPad and retina scanners, with others in development including insect robots (mimics of the film’s spider robots), facial recognition advertising billboards, crime prediction software and electronic paper. A much more recent example not featured in the book is the 2011 film Limitless, featuring a writer that is able to stimulate and access 100% of his brain at will by taking a nootropic drug. While the fictitious drug portrayed in the film is not yet a neurochemical reality, brain enhancement is a rising field of biomedical research, and may one day indeed yield a brain-boosting pill.

No other scientific feat has been a bigger beneficiary of diegetic prototyping than space travel, starting with 1929’s prophetic masterpiece Frau im Mond [Woman in the Moon], sponsored by the German Rocket Society and advised masterfully by Hermann Oberth, a pioneering German rocket research scientist. The first film to ever present the basics of rocket travel in cinema, and credited with the now-standard countdown to zero before launch in real life, Frau im Mond also featured a prototype of the liquid-fuel rocket and inspired a generation of physicists to contribute to the eventual realization of space travel. Destination Moon, a 1950 American sci-fi film about a privately financed trip to the Moon, was the first film produced in the United States to deal realistically with the prospect of space travel by utilizing the technical and screenplay input of notable science fiction author Robert A. Heinlein. Released seven years before the start of the USSR Sputnik program, Destination Moon set off a wave of iconic space films and television shows such as When Worlds Collide, Red Planet Mars, Conquest of Space and Star Trek in the midst of the 1950s and 1960s Cold War “space race” between the United States and Russia. What theoretical scientific feat will propel the next diegetic prototype? A mission to Mars? Space colonization? Anti-aging research? Advanced stem cell research? Time will only tell.

Ultimately, readers will enjoy Lab Coats in Hollywood for its engaging writing style, detailed exploration of the history of science in film and most of all, valuable advice from fellow scientists who transitioned from the lab to consulting on a movie set. Whether you are a sci-fi film buff or a research scientist aspiring to be a Hollywood consultant, you will find some aspect of this book fascinating. Especially given the rapid proliferation of science and technology content in movies (even those outside of the traditional sci-fi genre), and the input from the scientific community that it will surely necessitate, knowing the benefits and pitfalls of this increasingly in-demand career choice is as important as its significance in ensuring accurate portrayal of scientists to the general public.

~*ScriptPhD*~

***************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development.

Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

]]>

Battlestar Galactica is one of the defining, genre-changing science fiction shows of its, or perhaps any, time. The remake of the 1970s cult classic was sexy, sophisticated, and set a new standard for the science fiction shows and movies that will follow in its path. In addition to exploring staple concepts such as life, survival, politics and war, BSG reawakened its audience to science and its role in moral, ethical, and daily impact in our lives, especially given the technologically-driven era that we live in. “Writers were not allowed to jettison science for the sake of the story,” declares co-executive producer Jane Espenson in her foreword to the book. “Other than in specific instances of intentionally inexplicable phenomena, science was respected.” In an artful afterword, Richard Hatch (the original Apollo and Tom Zarek in the new series) concurs. “BSG used science not as a veneer, but as a key thematic component for driving many of the character stories… which is the art of science fiction.” The sustained use of complex, correct science as a plot element to the degree that was done in Battlestar Galactica is also a hallmark first. This is the topic of the new book The Science of Battlestar Galactica, newly released from Wiley Books, and written by Kevin R. Grazier, the very science advisor who consulted with the BSG writing staff on all things science, with a contribution from Wired writer Patrick DiJusto. Now, for the first time, everyone from casual fans to astrophysicists can gain insight into the research used to construct major stories and technology of the show—and learn some very cool science along the way. Our review of The Science of Battlestar Galactica (and our 100th blog post!) under the “continue reading” cut.

What is life? Seriously. I’m not asking one of those hypothetical existential questions that end up discussed ad nauseum in a dorm room at 3 AM. I’m asking the central question that Battlestar Galactica, and much of science fiction, is based around. The shortest section of The Science of Battlestar Galactica, “Life Began Out Here,” is its most poignant. No matter the conflict, subplot or theme explored on BSG, they ultimately reverted back to the idea of what constituted a living being, and what rights, if any, those beings possessed. It all boils down to cylons. What are they made of? How do their brains (potentially) work? How much information can they contain, and how is it processed from one dead cylon to its next incarnation? How could a cylon and a human mate successfully, and is their offspring (Hera Agathon) the Mitochondrial Eve of that society? How did they evolve? What is the biological difference between raiders, centurions, and humanoid cylons? Who can forget the ew gross factor of Boomer plugging her arm into the cylon computer system, but how could she do that, especially when she was made to act, feel and think as a human being? A brief, smart discussion on spontaneous evolution and basic biology gives way to a thoughtful evocation of our own efforts with artificial intelligence, and the responsibilities that it engenders. Take a look at the website of the MIT iGem Program, an annual competition to design biological systems that will operate in living cells from standard toolkits. Do some of their creations, including bacteria that eat industrial pollutants and treat lactose intolerance, constitute life, and are our own Cybernetic Life Nodes not too far away? The section ends in a fascinating debate over who we are more akin to—the humans of the Battlestar universe (as is widely assumed) or cylons. The answer would surprise you.

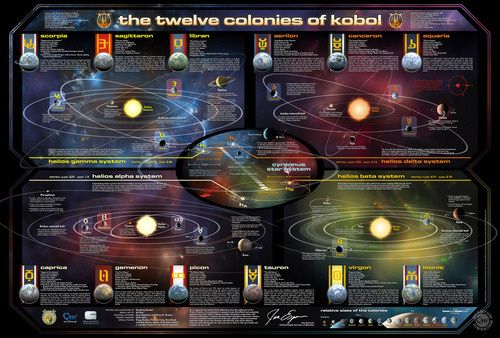

The middle of The Science of Battlestar Galactica, composed of “The Physics of Battlestar Galactica” and “The Twelve Colonies and The Rest of Space” reads largely like my college physics textbook, only with far cooler sample problems. If Apollo and Starbuck both launch their vipers at the same time and Starbuck coasts past Apollo, according to special relativity, who is moving? In perhaps the greatest implementation of Einstein’s famous theory in science fiction, special relativity explains how Starbuck could explain that she wasn’t a Cylon when she returned unharmed from the dead, and why her viper looked brand new. A special look at radiation particularly interested me, with a chemistry background, as it thoroughly delved into the chemistry and physics of radiation, heat-seeking missile weapons, DNA damage, and the power of nuclear weapons, both with fictional examples (the destruction of Caprica) and real (Japan and Chernobyl). The chapters on relativity (E=mc2) and the Lorentz Contraction reminded me of a seminar on dark energy that we covered at the Hollywood Laserium presented a year ago by Dr. Charles Baltay (NOT Baltar!), the man who was responsible for Pluto losing its planetary status. At the time, a lot of the concepts seemed a bit esoteric, but having read this book, are now elementary. Did you know, for example, that a supernova explosion is so powerful, it can briefly cause iron and other atoms remaining in the star to fuse into every naturally occurring element in the periodic table? Nifty, eh? Astronomy buffs, amateur and experienced, will enjoy the section on space, with a preamble on the formation of our galaxy and star systems to the 12 different planets of the Colonies, and how that many habitable planets could all be packed into such a dense area (see companion map below).

With perfect timing for the publication of The Science of BSG, Kevin R. Grazier and co-executive producer Jane Espenson have teamed up to create a plausible astronomy map of the 12 colonies of Battlestar Galactica. Find a larger, interactive version here.

One of the more fun aspects to watching BSG was the cornucopia of weapons, toys, and other electronics used by both humans and Cylons, a subject explored in the most meaty section of the whole book, “Battlestar Tech.” This includes a discussion of propulsion and how the Galactica’s jump drive might work, artificial gravity, a great chapter on the vipers and raptors as effective weapons, and positing how it is that Six was able to infiltrate the colonial computer infrastructure… besides the obvious, that is. I really enjoyed learning about Faraday cages, tachyon particles, brane cosmology, and what a back door is in computer programming, terms you can bet I will be throwing out casually at my next hoity-toity dinner party. The next time you rewatch an episode, and hear Mr. Gaeta utter a directive such as “We have a Cylon raider, CBDR, bearing 123 carom 45,” not only will you know exactly what he’s saying relative to the cartesian coordinates of the BSG space universe, but how this information is used to operate the complicated three-dimensional space system that the pilots have to operate in. Finally, critics such as myself of the dilapidated corded phones used aboard the Galactica will be interested to find out why they may have actually been a good idea in protecting the fleet from Cylon detection.

The ultimate selling point of this book is its ability to present material that will appeal to all fractions of a very diverse audience. The writing style is fluid, clever, informative and appropriately humorous in the way one would expect of a geeky sci-fi book (highlighted by a chapter on Cylon composition and detection thereof by Dr. Baltar written in dialogue format between an omniscient scientist and a smart-aleck fanboy). In fact, the co-authors merge their styles well enough so as to imagine that only one person wrote the book. Part textbook, part entertainment, part series companion, The Science of Battlestar Galactica is concomitantly smart, complicated, approachable and difficult—it does not surprise us one bit that in the couple of short months since its wide release, talk of numerous literary awards has already been circling. In between lessons on basic biology, astrophysics, energy and basic engineering are sprinkled delightful vignettes of actual on-set problem solving involving science. My favorites included plausible ways Cylons could download their information as they’re reborn (get ready for some serious computer-speak here!), an excellent explanation of Dr. Baltar’s mysterious Cylon detector, radiation and the difference between uninhabitable ‘dead Earth’ and barely habitable New Caprica, and the revelation by Dr. Grazier of how he had to—in a frantic period of 24 sleepless hours—construct a theory as to how the FTL drive works for an episode-specific reason. Much like the show it is based on, this book asks as many questions as it answers, most notably on social parables within our own world. Are we on our way to building Cylon artificial intelligence? Could our computer infrastructure ever get compromised like the ones on Caprica? Would we ever be able to travel to parallel universes, and what would be the implications of life forms besides our own? How might they even detect our presence?

Read our in-depth interview with Kevin R. Grazier here

Join our our Facebook fan page for a special giveaway commemorating the release of The Science of Battlestar Galactica and our 100th blog post. Now if you’ll excuse me, having read and absorbed this illuminating volume, I have been inspired to go and watch the entire series from start to finish all over again!

~*ScriptPhD*~

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development.

Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

]]>

One of the most captivating books of 2010 was not a gory science-fiction thriller or a gripping end-of-the world page-turner, though its subject matter is equally engrossing and out of the ordinary. It is about somewhat crazy people doing crazy things as seen through the lenses of the man that has been treating them for decades. The Naked Lady Who Stood On Her Head is the first psych ward memoir, a tale of a curious doctor/scientist and his most extreme, bizarre, and sometimes touching cases from the nation’s most prestigious neurology centers and universities. Included in ScriptPhD.com’s review is a podcast interview with Dr. Small, as well as the opportunity to win a free autographed copy of his book. Our end-of-the year science library pick is under the “continue reading” cut.

Gary Small is a very unlikely candidate for the chaos that many of us confuse with a psych ward. Whether it was the frantic psych consults on ER or fond remembrance of Jack Nicholson and his cohorts in One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest, most of us have a natural association of psychiatry with insanity or pandemonium. Meeting Dr. Small in real life is the antithesis of these scenarios. Warm, welcoming, serene and genuinely affable, his voice translates directly from the pages of his latest book. Told in chronological order—starting with

a young, curious, inexperienced intern at Harvard’s Massachussetts General Hospital to his tenure as a world-renowned neuroscientist at UCLA—The Naked Lady Who Stood On Her Head feels like an enormous learning and growing experience for Dr. Small, his patients, and the reader.

The scene plays out like a standard medical drama or movie. In the beginning, the young, bright-eyed, bushy-tailed, trepidatious doctor is exploring while learning the ropes on duty. There is, in the self-titled chapter, literally a naked lady standing on her head in the middle of a Boston psych ward. Dr. Small is the only doctor that can cure her baffling ailment, but in doing so, only begins to peel away at what is really troubling her. There is a bevvy of inexplicable fainting schoolgirls afflicting the Boston suburbs. Only through a fresh pair of eager eyes is the root cause attained, a cause that to this day sets the standard for mass hysteria treatment nationwide. And there is a mute hip painter from Venice beach, immobile for weeks until Small, fighting the rigid senior attendings, gets to the unlikely diagnosis. As the book, and Dr. Small’s career, flourishes, we meet a WebMD mom, a young man literally blinded by his family’s pressure, a man whose fiancé’s obsession with Disney characters resurfaces a painful childhood secret, and Dr. Small’s touching story of having to watch as the mentor he introduced at the book’s beginning hires him as a therapist so that he can diagnose his teacher’s dementia. Ultimately, all of the characters of The Naked Lady Who Stood on Her Head, and Dr. Small’s dedication and respect, have a common thread. They are real, they are diverse, and they are us. Psych patients are not one-dimensional figments of a screenwriter’s imagination. They are the brother who has childhood trauma, the friend with a dysfunctional or abusive family, the husband or wife with a rare genetic predisposition, and all of us are but one degree away from the abnormal behavior that these conditions can ignite. In his book, Dr. Small has pulled back the curtain of a notoriously secretive and mysterious field. It’s a riveting reveal, and absolutely worth an appointment. The Naked Lady Who Stood On Her Head has been optioned by 20th Century Fox, and may be coming to your televisions soon!

Podcast Interview

In addition to his latest novel, Gary Small is the author of the best-selling global phenomenon The Memory Bible: An Innovative Strategy For Keeping Your Brain Young and a regular contributor to The Huffington Post (several excellent recent articles can be found here and here). His seminal research on Alzheimer’s disease, aging and brain training has appeared in recent articles in NPR and Newsweek. A seminal brain imaging study recently completed in his laboratory garnered worldwide media attention for suggesting that Google searching can stimulate the brain and literally keep aging brains agile. Dr. Small regularly updates his research and musings on his personal blog.

ScriptPhD.com sat down for a one-on-one podcast with Dr. Small and discussed inspiration for the book, and how it conveys the inner thought process of a psychiatrist through their many interesting cases. In our podcast, we discuss how media and on-screen portrayal of psychiatrists contribute to people’s perceptions of the field, how the themes of empathy and humanity are indellibly woven into case studies, the challenges and fullfillment of psychiatry and the contribution of pop culture in modern psychoses.

~*ScriptPhD*~

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development. Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

As Comic-Con winds down on the shortened Day 4, we conclude our coverage with two panels that exemplify what Comic-Con is all about. As promised, we dissect the “Comics Design” panel of the world’s top logo designers deconstructing their work, coupled with images of their work. We also bring you an interesting panel of ethnographers, consisting of undergraduate and graduate student, studying the culture and the varying forces that shape Comic-Con. Seriously, they’re studying nerds! Finally, we are delighted to shine our ScriptPhD.com spotlight on new sci-fi author Charles Yu, who presented his new novel at his first (of what we are sure are many) Comic-Con appearance. We sat down and chatted with Charles, and are pleased to publish the interview. And of course, our Day 4 Costume of the Day. Comic-Con 2010 (through the eyes of ScriptPhD.com) ends under the “continue reading” cut!

Comics Design

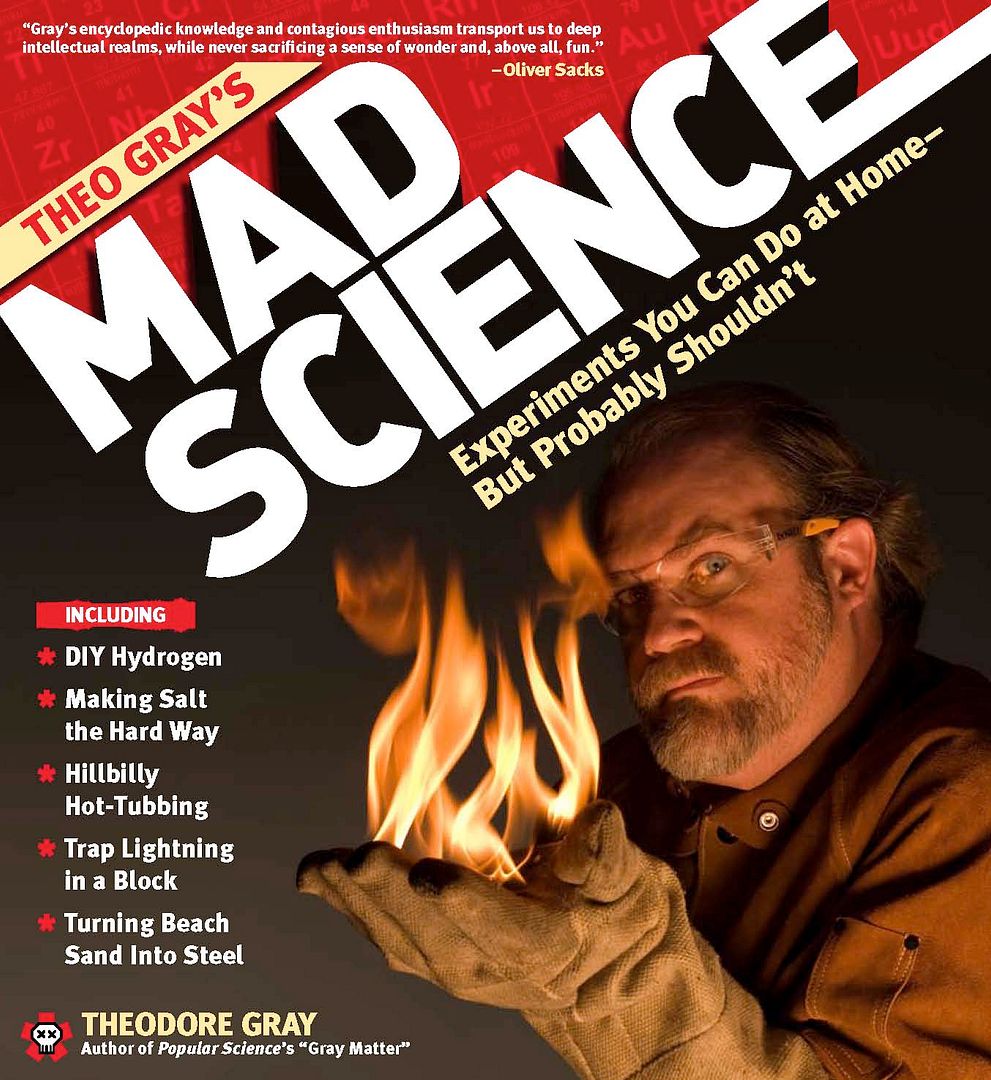

We are not ashamed to admit that here at ScriptPhD.com, we are secret design nerds. We love it, particularly since good design so often elevates the content of films, television, and books, but is a relatively mysterious process. One of THE most fascinating panels that we attended at Comic-Con 2010 was on the design secrets behind some of your favorite comics and book covers. A panel of the world’s leading designers revealed their methodologies (and sometimes failures) in the design process behind their hit pieces, lifting the shroud of secrecy that designers often envelop themselves in. An unparalleled purview into the mind of the designer, and the visual appeal that so often subliminally contributes to the success of a graphic novel, comic, or even regular book. We do, as it turns out, judge books by their covers.

As promised, we revisit this illuminating panel, and thank Christopher Butcher, co-founder of The Toronto Comic Arts Festival and co-owner of The Beguiling, Canada’s finest comics bookstore. Chris was kind enough to provide us with high-quality images of the Comics Design panel’s work, for which we at ScriptPhD.com are grateful. Chris had each of the graphic artists discuss their work with an example of design that worked, and design that didn’t (if available or so inclined). The artist was asked to deconstruct the logo or design and talk about the thought process behind it.

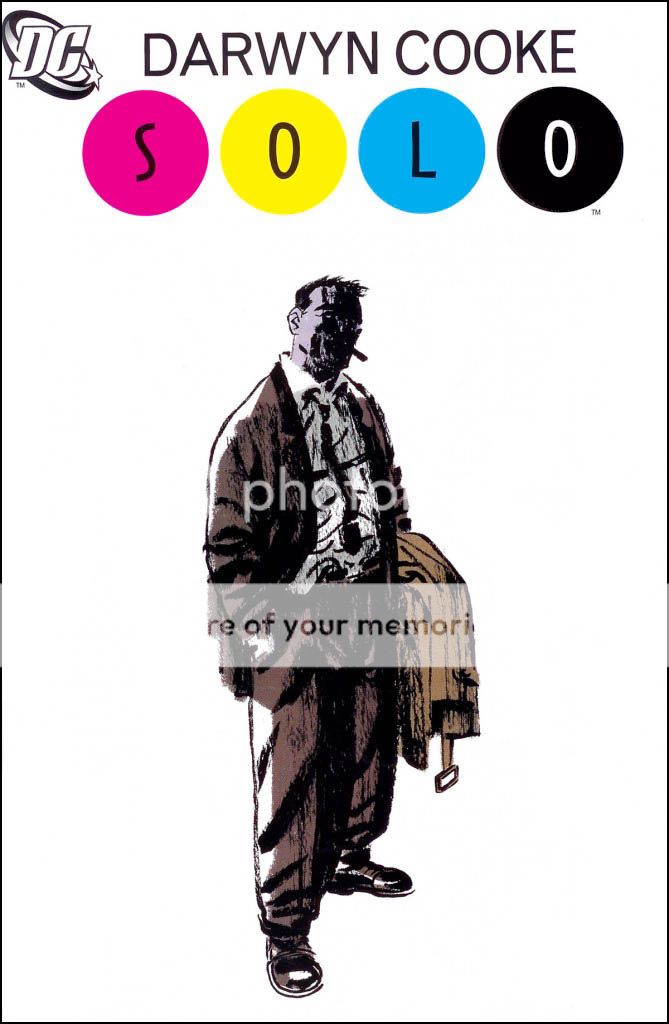

Mark Ciarello – (art + design director at DC Comics)

Mark chose to design the cover of this book with an overall emphasis on the individual artist. Hence the white space on the book, and a focus on the logo above the “solo” artist.

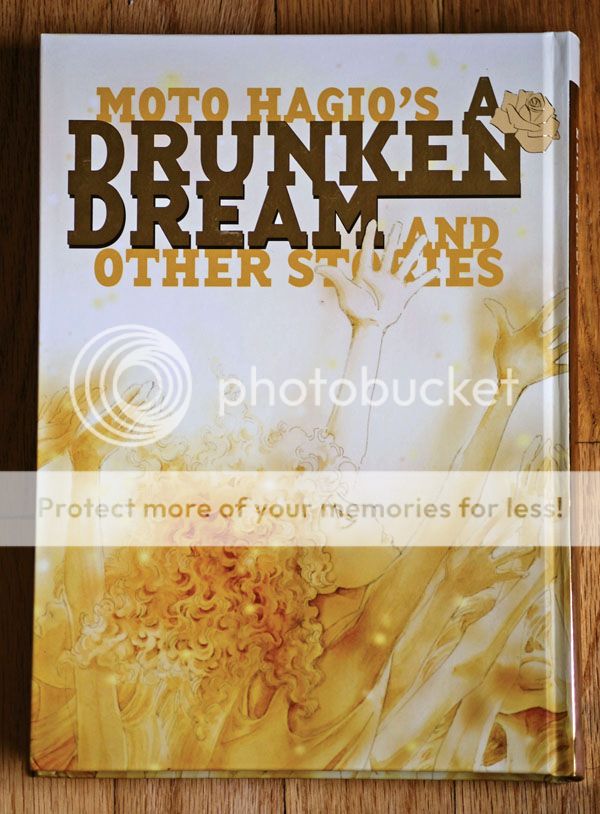

Adam Grano – (designer at Fantagraphics)

Adam took the title of this book quite literally, and let loose with his design to truly emphasize the title. He called it “method design.” He wanted the cover to look like a drunken dream.

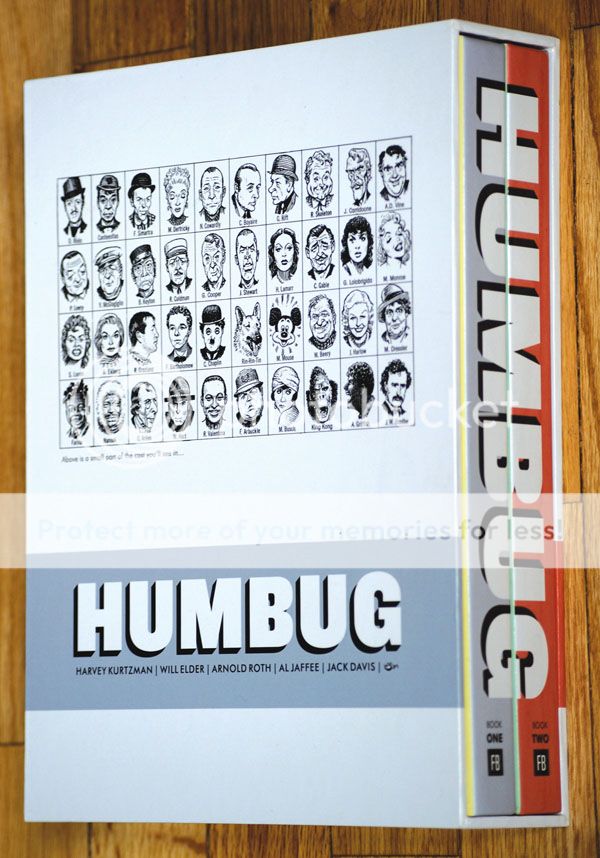

For the Humbug collection, Grano tried hard not to impress too much of himself (and his tastes) in the design of the cover. He wanted to inject simplicity in a project that would stand the test of time, because it was a collector’s series.

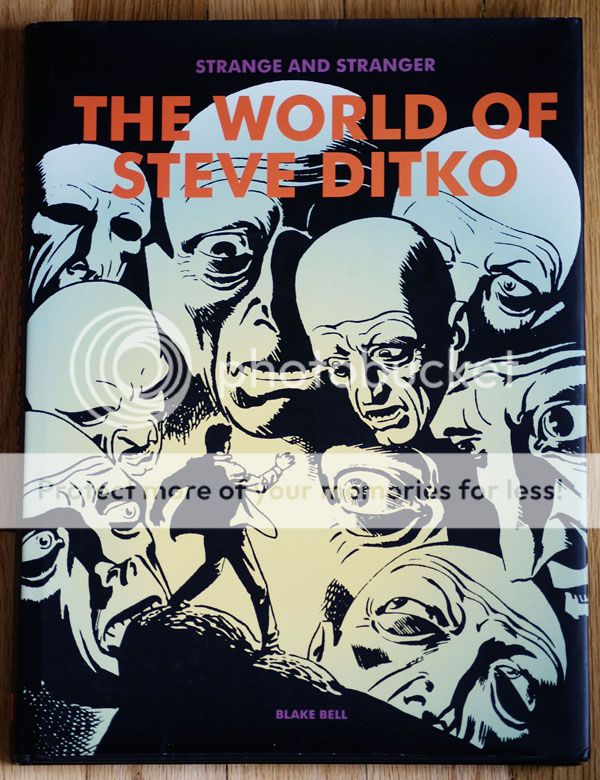

Grano considered this design project his “failure.” It contrasts greatly with the simplicity and elegance of Humbug. He mentioned that everyone on the page is scripted and gridded, something that designers try to avoid in comics.

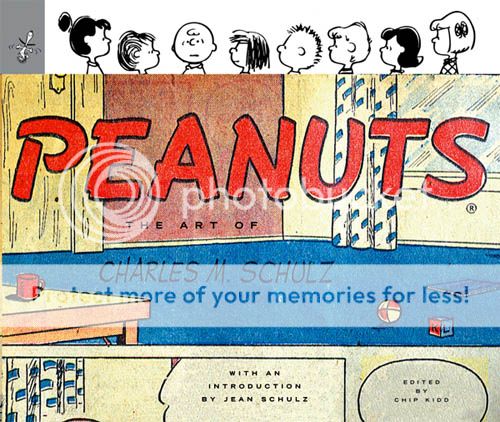

Chip Kidd – (designer at Random House)

Chip Kidd had the honor of working on the first posthumous Peanuts release after Charles M. Schultz’s death, and took to the project quite seriously. In the cover, he wanted to deconstruct a Peanuts strip. All of the human element is taken out of the strip, with the characters on the cover up to their necks in suburban anxiety.

Kidd likes this cover because he considers it an updated spin on Superman. It’s not a classic Superman panel, so he designed a logo that deviated from the classic “Superman” logo to match.

Kidd chose this as his design “failure”, but not the design itself. The cover represents one of seven volumes, in which the logo pictured disintegrates by the seventh issue, to match the crisis in the title. Kidd’s only regret here is that he was too subtle. He wishes he’d chosen to start the logo disintegration progression sooner, as there’s very little difference between the first few volumes.

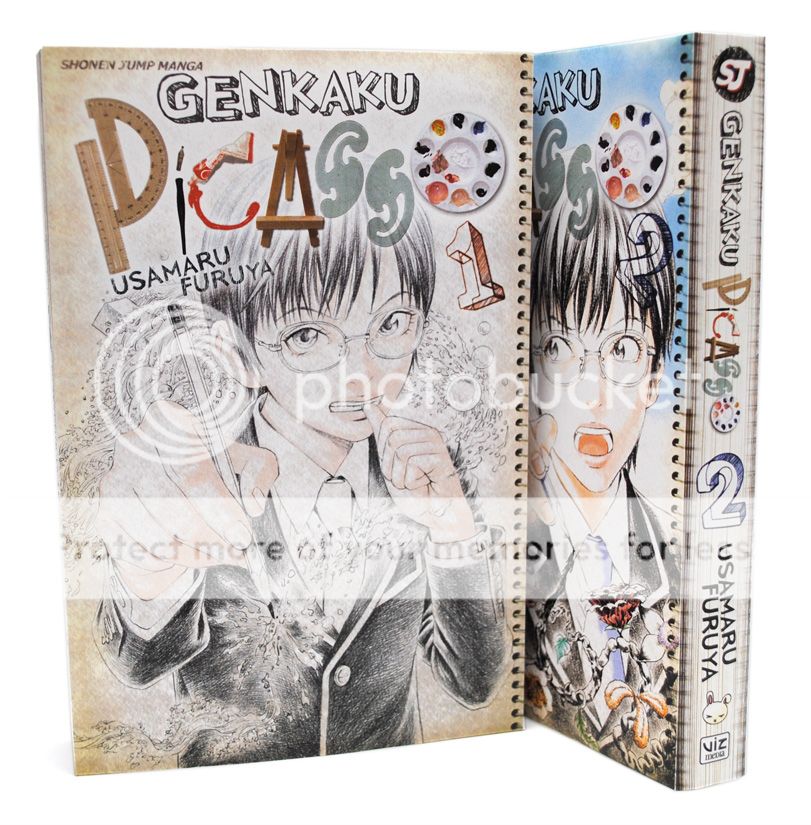

Fawn Lau – (designer at VIZ)

Fawn was commissioned to redesign this book cover for an American audience. Keeping this in mind, and wanting the Japanese animation to be more legible for the American audience, she didn’t want too heavy-handed of a logo. In an utterly genius stroke of creativity, Lau went to an art store, bought $70 worth of art supplies, and played around with them until she constructed the “Picasso” logo. Clever, clever girl!

Mark Siegel – (First Second Books)

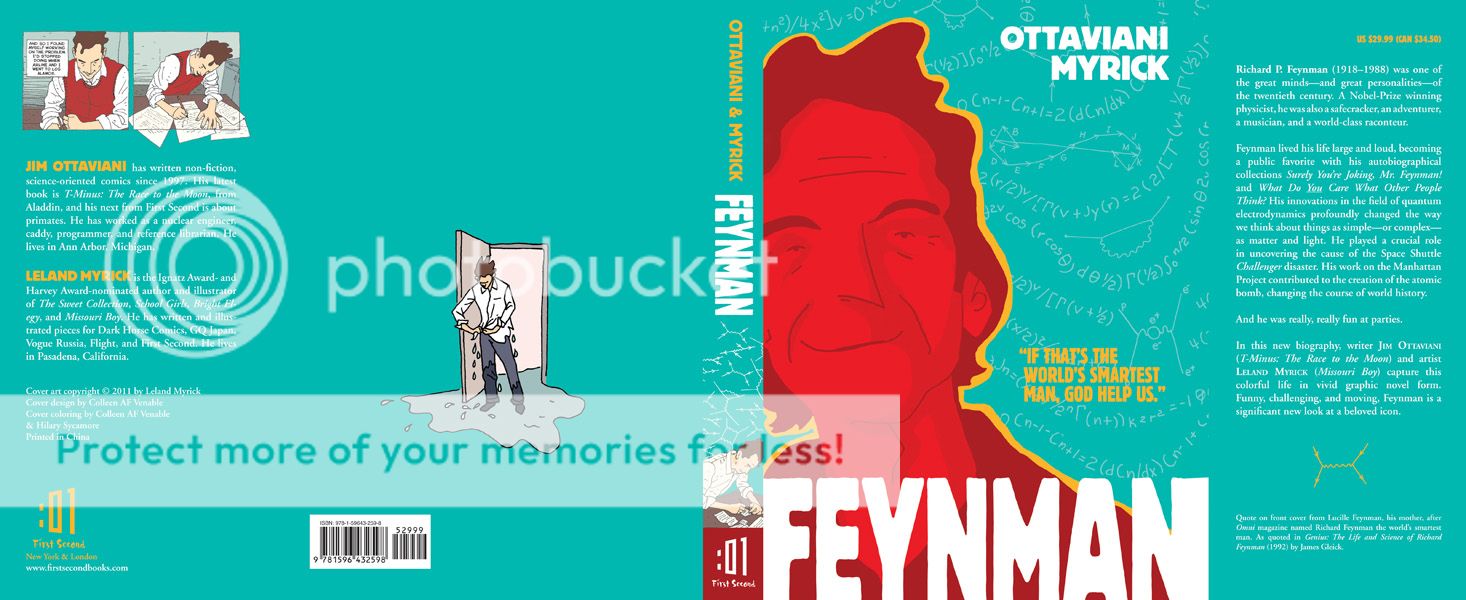

Mark Siegel was hired to create the cover of the new biography Feynman, an eponymous title about one of the most famous physicists of all time. Feynman was an amazing man who lived an amazing life, including a Nobel Prize in physics in 1965. His biographer, Ottaviani Myrick, a nuclear physicist and speed skating champion, is an equally accomplished individual. The design of the cover was therefore chosen to reflect their dynamic personalities. The colors were chosen to represent the atomic bomb and Los Alamos, New Mexico, where Feynman assisted in the development of The Manhattan Project. Incidentally, the quote on the cover – “If that’s the world’s smartest man, God help us!” – is from Feynman’s own mother.

Keith Wood – (Oni Press)

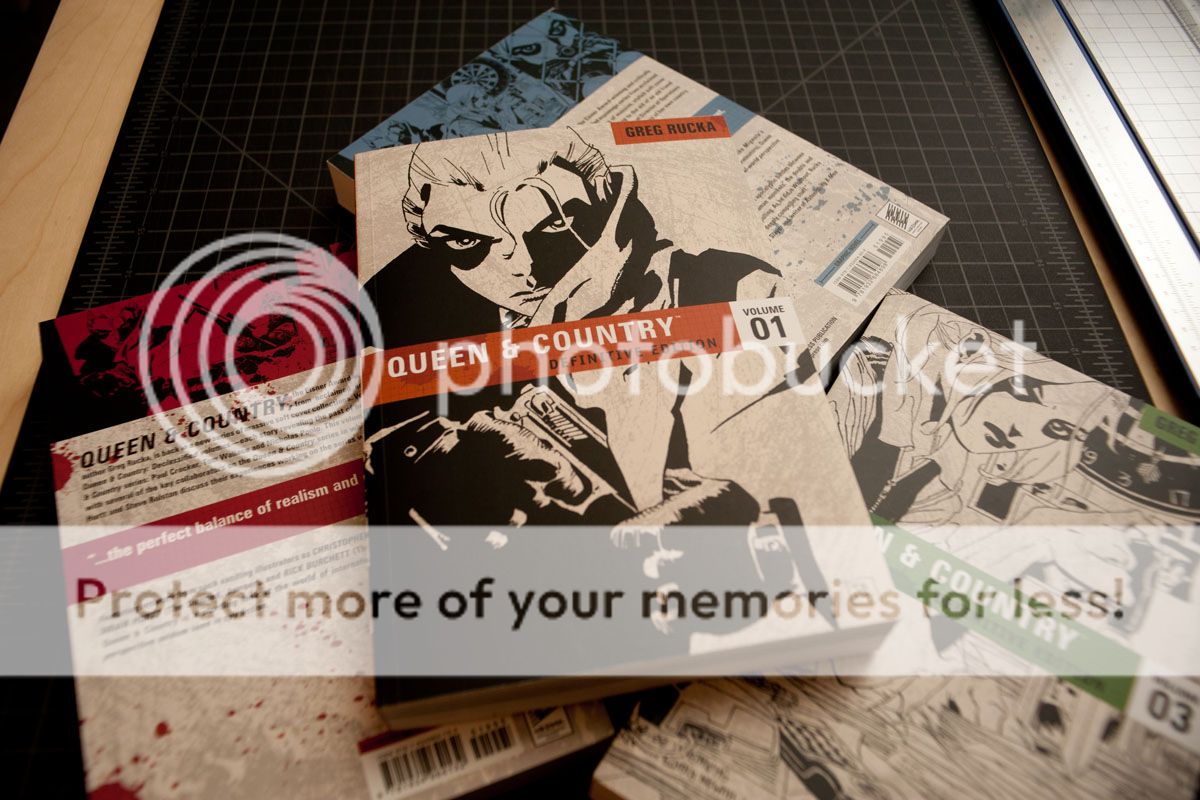

Wood remarked that this was the first time he was able to do design on a large scale, which really worked for this project. He chose a very basic color scheme, again to emphasize a collection standing the test of time, and designed all the covers simultaneously, including color schemes and graphics. He felt this gave the project a sense of connectedness.

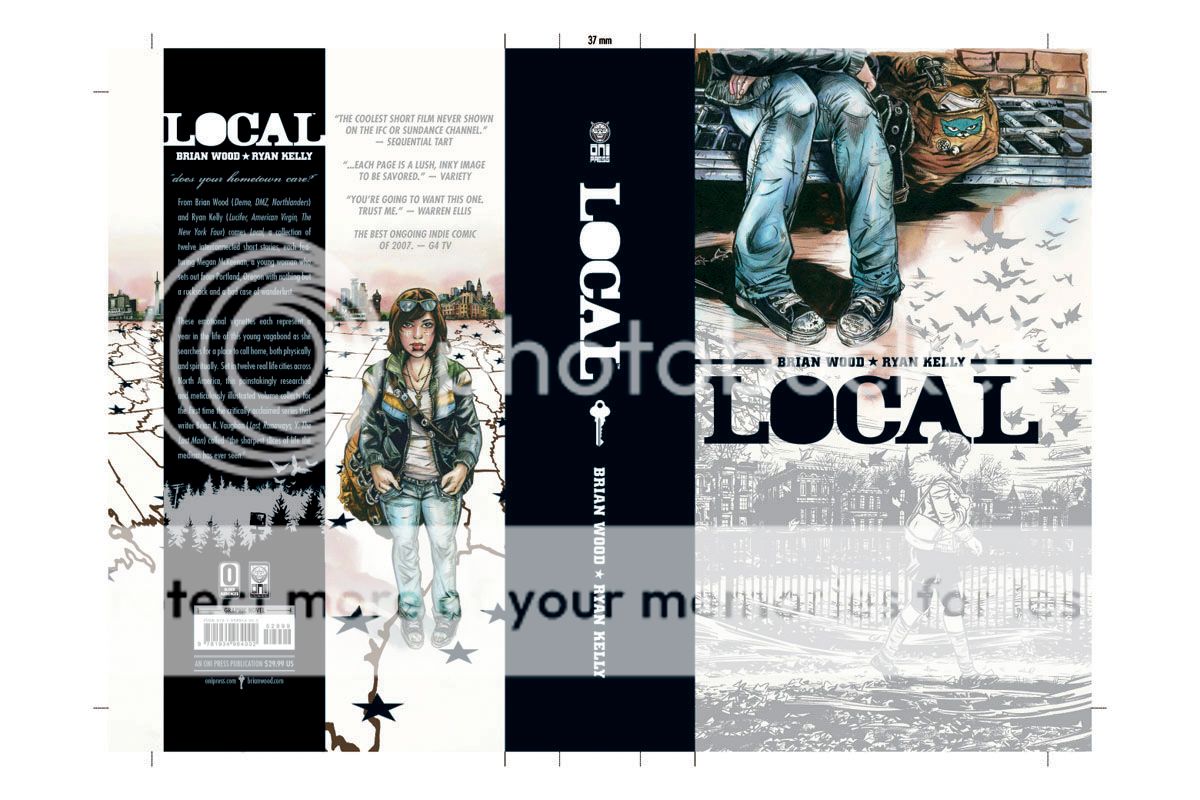

Wood chose a pantone silver as the base of this design with a stenciled typeface meant to look very modern. The back of the cover and the front of the cover were initially going to be reversed when the artists first brought him the renderings. However, Wood felt that since the book’s content is about the idea of a girl’s traveling across the United States, it would be more compelling and evocative to use feet/baggage as the front of the book. He was also the only graphic artist to show a progression of 10-12 renderings, playing with colors, panels and typeface, that led to the final design. He believes in a very traditional approach to design, which includes hand sketches and multiple renderings.

The Culture of Popular Things: Ethnographic Examinations of Comic-Con 2010

Each year, for the past four years, Comic-Con ends on an academic note. Matthew J. Smith, a professor at Wittenberg University in Ohio, takes along a cadre of students, graduate and undergraduate, to study Comic-Con; the nerds, the geeks, the entertainment component, the comics component, to ultimately understand the culture of what goes on in this fascinating microcosm of consumerism and fandom. By culture, the students embrace the accepted definition by famous anthropologist Raymond J. DeMallie: “what is understood by members of a group.” The students ultimately wanted to ask why people come to Comic-Con in general. They are united by the general forces of being fans; this is what is understood in their group. After milling around the various locales that constituted the Con, the students deduced that two ultimate forces were simultaneously at play. The fan culture drives and energizes the Con as a whole, while strong marketing forces were on display in the exhibit halls and panels.

Maxwell Wassmann, a political economy student at Wayne State University, pointed out that “secretly, what we’re talking about is the culture of buying things.” He compared Comic-Con as a giant shopping mall, a microcosm of our economic system in one place. “If you’ve spent at least 10 minutes at Comic-Con,” he pointed out, “you probably bought something or had something tried to be sold to you. Everything is about marketing.” As a whole, Comic-Con is subliminally designed to reinforce the idea that this piece of pop culture, which ultimately advertises an even greater subset of pop culture, is worth your money. Wassmann pointed out an advertising meme present throughout the weekend that we took notice of as well—garment-challenged ladies advertising the new Green Hornet movie. The movie itself is not terribly sexy, but by using garment-challenged ladies to espouse the very picture of the movie, when you leave Comic-Con and see a poster for Green Hornet, you will subconsciously link it to the sexy images you were exposed to in San Diego, greatly increasing your chances of wanting to see the film. By contrast, Wassmann also pointed out that there is a concomitant old-town economy happening; small comics. In the fringes of the exhibition center and the artists’ space, a totally different microcosm of consumerism and content exchange.

Kane Anderson, a PhD student at UC Santa Barbara getting his doctorate in “Superheroology” (seriously, why didn’t I think of that back in graduate school??), came to San Diego to observe how costumes relate to the superhero experience. To fully absorb himself in the experience, and to gain the trust of Con attendees that he’d be interviewing, Anderson came in full costume (see above picture). Overall, he deduced that the costume-goers, who we will openly admit to enjoying and photographing during our stay in San Diego, act as goodwill ambassadors for the characters and superheroes they represent. They also add to the fantasy and adventure of Comic-Con goers, creating the “experience.” The negative side to this is that it evokes a certain “looky-loo” effect, where people are actively seeking out, and singling out, costume-wearers, even though they only constitute 5% of all attendees.

Tanya Zuk, a media masters student from the University of Arizona, and Jacob Sigafoos, an undergraduate communications major at Wittenberg University, both took on the mighty Hollywood forces invading the Con, primarily the distribution of independent content, an enormous portion of the programming at Comic-Con (and a growing presence on the web). Zuk spoke about original video content, more distinctive of new media, is distributed primarily online. It allows for more exchange between creators and their audience than traditional content (such as film and cable television), and builds a community fanbase through organic interaction. Sigafoos expanded on this by talking about how to properly market such material to gain viral popularity—none at all! Lack of marketing, at least traditional forms, is the most successful way to promote a product. Producing a high-quality product, handing it off to friends, and promoting through social media is still the best way to grow a devoted following.

And speaking of Hollywood, their presence at Comic-Con is undeniable. Emily Saidel, a Master’s student at NYU, and Sam Kinney, a business/marketing student at Wittenberg University, both took on the behemoth forces of major studios hawking their products in what originally started out as a quite independent gathering. Saidel tackled Hollywood’s presence at Comic-Con, people’s acceptance/rejection thereof, and how comics are accepted by traditional academic disciplines as didactic tools in and of themselves. The common thread is a clash between the culture and the community. Being a member of a group is a relatively simple idea, but because Comic-Con is so large, it incorporates multiple communities, leading to tensions between those feeling on the outside (i.e. fringe comics or anime fans) versus those feeling on the inside (i.e. the more common mainstream fans). Comics fans would like to be part of that mainstream group and do show interest in those adaptations and changes (we’re all movie buffs, after all), noted Kinney, but feel that Comic-Con is bigger than what it should be.

But how much tension is there between the different subgroups and forces? The most salient example from last year’s Con was the invasion of the uber-mainstream Twilight fans, who not only created a ruckus on the streets of San Diego, but also usurped all the seats of the largest pavilion, Hall H, to wait for their panel, locking out other fans from seeing their panels. (No one was stabbed.) In reality, the supposed clash of cultures is blown out of proportion, with most fans not really feeling the tension. To boot, Seidel pointed out that tension isn’t necessarily a bad thing, either. She gave a metaphor of a rubber band, which only fulfills its purpose with tension. The different forces of Comic-Con work in different ways, if sometimes imperfectly. And that’s a good thing.

Incidentally, if you are reading this and interested in participating in the week-long program in San Diego next year, visit the official website of the Comic-Con field study for more information. Some of the benefits include: attending the Comic-Con programs of your choice, learning the tools of ethnographic investigation, and presenting the findings as part of a presentation to the Comics Arts Conference. Dr. Matthew Smith, who leads the field study every year, is not just a veteran attendee of Comic-Con, but also the author of The Power of Comics.

COMIC-CON SPOTLIGHT ON: Charles Yu, author of How To Live Safely in a Science Fictional Universe.

Here at ScriptPhD.com, we love hobnobbing with the scientific and entertainment elite and talking to writers and filmmakers at the top of their craft as much as the next website. But what we love even more is seeking out new talent, the makers of the books, movies and ideas that you’ll be talking about tomorrow, and being proud to be the first to showcase their work. This year, in our preparation for Comic-Con 2010, we ran across such an individual in Charles Yu, whose first novel, How To Live Safely in a Science Fictional Universe premieres this fall, and who spoke about it at a panel over the weekend. We had an opportunity to have lunch with Charles in Los Angeles just prior Comic-Con, and spoke in-depth about his new book, along with the state of sci-fi in current literature. We’re pretty sure Charles Yu is a name science fiction fans are going to be hearing for some time to come. ScriptPhD.com is proud to shine our 2010 Comic-Con spotlight on Charles and his debut novel, which is available September 7, 2010.

How To Live Safely in a Science Fictional Universe is the story of a son searching for his father… through quantum-space time. The story takes place on Minor Universe 31, a vast story-space on the outskirts of fiction, where paradox fluctuates like the stock market, lonely sexbots beckon failed protagonists, and time travel is serious business. Every day, people get into time machines and try to do the one thing they should never do: try to change the past. That’s where the main character, Charles Yu, time travel technician, steps in. Accompanied by TAMMY (who we consider the new Hal), an operating system with low self-esteem, and a nonexistent but ontologically valid dog named Ed, Charles helps save people from themselves. When he’s not on the job, Charles visits his mother (stuck in a one-hour cycle, she makes dinner over and over and over) and searches for his father, who invented time travel and then vanished.

Questions for Charles Yu

ScriptPhD.com: Charles, the story has tremendous traditional sci-fi roots. Can you discuss where the inspiration for this came from?

Charles Yu: Well the sci-fi angle definitely comes from being a kid in the 80s, when there were blockbuster sci-fi things all over the place. I’ve always loved [that time], as a casual fan, but also wanted to write it. I didn’t even start doing that until after I’d graduated from law school. I did write, growing up, but I never wrote fiction—I didn’t think I’d be any good at it! I wrote poetry in college, minored in it, actually. Fiction and poetry are both incredibly hard, and poetry takes more discipline, but at least when I failed in my early writing, it was a 100 words of failure, instead of 5,000 words of it.

SPhD: What were some of your biggest inspirations growing up (television or books) that contributed to your later work?

CY: Definitely The Foundation Trilogy. I remember reading that in the 8th grade, and I remember spending every waking moment reading, because it was the greatest thing I’d ever read. First of all, I was in the 8th grade, so I hadn’t read that many things, but the idea that Asimov created this entire self-contained universe, it was the first time that I’d been exposed to that idea. And then to have this psychohistory on top, it was kind of trippy. Psychohistory is the idea that social sciences can be just as rigorously captured with equations as any physical science. I think that series of books is the main thing that got me into sci-fi.

SPhD: Any regrets about having named the main character after yourself?

CY: Yes. For a very specific reason. People in my life are going to think it’s biographical, which it’s very much not. And it’s very natural for people to do that. And in my first book of short stories, none of the main characters was named after anyone, and still I had family members that asked if that was about our family, or people that gave me great feedback but then said, “How could you do that to your family?” And it was fiction! I don’t think the book could have gotten written had I not left that placeholder in, because the one thing that drove any sort of emotional connection for the story for me was the idea of having less things to worry about. The other thing is that because the main character is named after you, as you’re writing the book, it acts as a fuel or vector to help drive the emotional completion.

SPhD: In the world of your novel, people live in a lachrymose, technologically-driven society. Any commentary therein whatsoever on the technological numbing of our own current culture?

CY: Yes. But I didn’t mean it as a condemnation, in a sense. I wouldn’t make an overt statement about technology and society, but I am more interested in the way that technology can sometimes not connect people, but enable people’s tendency to isolate themselves. Certainly, technology has amazing connective possibilities, but that would have been a much different story, obviously. The emotional plot-level core of this book is a box. And that sort of drove everything from there. The technology is almost an emotional technology that [Charles, the main character] has invented with his dad. It’s a larger reflection of his inability to move past certain limitations that he’s put on himself.

SPhD: What drives Charles, the main character of this book?

CY: What’s really driving Charles emotionally is looking for his dad. But more than that, is trying to move through time, to navigate the past without getting stuck in it.

SPhD: Both of his companions are non-human. Any significance to that?

CY: It probably speaks more to my limitations as a writer [laughs]. That was all part of the lonely guy type that Charles is being portrayed as. If he had a human with him, he’d be a much different person.

SPhD: The book abounds in scientific jargon and technological terminology, which is par for the course in science fiction, but was still very ambitious. Do you have high expectations of the audience that will read this book?

CY: Yeah. I was just reading an interview where the writer essentially said “You can never go wrong by expecting too much [of your audience].” You can definitely go wrong the other way, because that would come off as terrible, or assuming that you know more. But actually, my concerns were more in the other direction, because I knew I was playing fast and loose with concepts that I know I don’t have a great grasp of. I’m writing from the level of amateur who likes reading science books, and studied science in college—an entertainment layreader. My worry was whether I was BSing too much [of the science]. There are parts where it’s clearly fictional science, but there are other parts that I cite things that are real, and is anyone who reads this who actually knows something about science going to say “What the heck is this guy saying?”

SPhD: How To Live… is written in a very atavistic, retro 80s style of science fiction, and really reminded me of the best of Isaac Asimov. How do you feel about the current state of sci-fi literature as relates to your book?

CY: Two really big keys for me, and things I was thinking about while writing [this book], were one, there is kind of a kitchiness to sci-fi, and I think that’s kind of intentional. It has a kind of do-it-yourself aesthetic to it. In my book, you basically have a guy in the garage with his dad, and yes the dad is an engineer, but it’s in a garage without great equipment, so it’s not going to look sleek, you can imagine what it’s going to look like—it’s going to look like something you’d build with things you have lying around in the garage. On the other hand, it is supposed to be this fully realized time machine, and you’re not supposed to be able to imagine it. Even now, when I’m in the library in the science-fiction section, I’ll often look for anthologies that are from the 80s, or the greatest time travel stories from the 20th Century that cover a much greater range of time than what’s being published now. It’s almost like the advancement of real-world technology is edging closer to what used to be the realm of science fiction. The way that I would think about that is that it’s not exploting what the real possibility of science fiction is, which is to explore a current world or any other completely strange world, but not a world totally envisionable ten years from now. You end up speculating on what’s possible or what’s easily extrapollatable from here; that’s not necessarily going to make for super emotional stories.

Charles Yu is a writer and attorney living in Los Angeles, CA.

Last, but certainly not least, is our final Costume of the Day. We chose this young ninja not only because of the coolness of his costume, but because of his quick wit. As we were taking the snapshot he said, “I’m smiling, you just can’t see it.” And a check mate to you, young sir.

Incidentally, you can find much more photographic coverage of Comic-Con on our Facebook fan page. Become a fan, because this week, we will be announcing Comic-Con swag giveaways that only Facebook fans are eligible for.

~*ScriptPhD*~

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development.

Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

]]>

Dr. Mark Changizi, a cognitive science researcher, and professor at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, is one of the most exciting rising stars of science writing and the neurobiology of popular culture phenomena. His latest book, The Vision Revolution, expounds on the evolution and nuances of the human eye—a meticulously designed, highly precise technological marvel that allows us to have superhuman powers. You heard me right; superhuman! X-ray vision, color telepathy, spirit reading, and even seeing into the future. Dr. Changizi spoke about these ideas, and how they might be applied to everything from sports stars with great hand-eye coordination to modern reading and typeface design with us in ScriptPhD.com’s inaugural audio podcast. He also provides an exclusive teaser for his next book with a guest post on the surprising mindset that makes for creative people. Read Dr. Changizi’s guest post and listen to the podcast under the “continue reading” cut.

You are an idea-monger. Science, art, technology—it doesn’t matter which. What matters is that you’re all about the idea. You live for it. You’re the one who wakes your spouse at 3am to describe your new inspiration. You’re the person who suddenly veers the car to the shoulder to scribble some thoughts on the back of an unpaid parking ticket. You’re the one who, during your wedding speech, interrupts yourself to say, “Hey, I just thought of something neat.” You’re not merely interested in science, art or technology, you want to be part of the story of these broad communities. You don’t just want to read the book, you want to be in the book—not for the sake of celebrity, but for the sake of getting your idea out there. You enjoy these creative disciplines in the way pigs enjoy mud: so up close and personal that you are dripping with it, having become part of the mud itself.

Enthusiasm for ideas is what makes an idea-monger, but enthusiasm is not enough for success. What is the secret behind people who are proficient idea-mongers? What is behind the people who have a knack for putting forward ideas that become part of the story of science, art and technology? Here’s the answer many will give: genius. There are a select few who are born with a gift for generating brilliant ideas beyond the ken of the rest of us. The idea-monger might well check to see that he or she has the “genius” gene, and if not, set off to go monger something else.

Luckily, there’s more to having a successful creative life than hoping for the right DNA. In fact, DNA has nothing to do with it. “Genius” is a fiction. It is a throw-back to antiquity, where scientists of the day had the bad habit of “explaining” some phenomenon by labeling it as having some special essence. The idea of “the genius” is imbued with a special, almost magical quality. Great ideas just pop into the heads of geniuses in sudden eureka moments; geniuses make leaps that are unfathomable to us, and sometimes even to them; geniuses are qualitatively different; geniuses are special. While most people labeled as a genius are probably somewhat smart, most smart people don’t get labeled as geniuses.

I believe that it is because there are no geniuses, not, at least, in the qualitatively-special sense. Instead, what makes some people better at idea-mongering is their style, their philosophy, their manner of hunting ideas. Whereas good hunters of big game are simply called good hunters, good hunters of big ideas are called geniuses, but they only deserve the moniker “good idea-hunter.” If genius is not a prerequisite for good idea-hunting, then perhaps we can take courses in idea-hunting. And there would appear to be lots of skilled idea-hunters from whom we may learn.

There are, however, fewer skilled idea-hunters than there might at first seem. One must distinguish between the successful hunter, and the proficient hunter – between the one-time fisherman who accidentally bags a 200 lb fish, and the experienced fisherman who regularly comes home with a big one (even if not 200 lbs). Communities can be creative even when no individual member is a skilled idea-hunter. This is because communities are dynamic evolving environments, and with enough individuals, there will always be people who do generate fantastically successful ideas. There will always be successful idea-hunters within creative communities, even if these individuals are not skilled idea-hunters, i.e., even if they are unlikely to ever achieve the same caliber of idea again. One wants to learn to fish from the fisherman who repeatedly comes home with a big one; these multiple successful hunts are evidence that the fisherman is a skilled fish-hunter, not just a lucky tourist with a record catch.

And what is the key behind proficient idea-hunters? In a word: aloofness. Being aloof—from people, from money, from tools, and from oneself—endows one’s brain with amplified creativity. Being aloof turns an obsessive, conservative, social, scheming status-seeking brain into a bubbly, dynamic brain that resembles in many respects a creative community of individuals. Being a successful idea-hunter requires understanding the field (whether science, art or technology), but acquiring the skill of idea-hunting itself requires taking active measures to “break out” from the ape brains evolution gave us, by being aloof.

I’ll have more to say about this concept over the next year, as I have begun writing my fourth book, tentatively titled Aloof: How Not Giving a Damn Maximizes Your Creativity. (See here and here for other pieces of mine on this general topic.) In the meantime, given the wealth of creative ScriptPhD.com readers and contributors, I would be grateful for your ideas in the comment section about what makes a skilled idea-hunter. If a student asked you how to be creative, how would you respond?

Mark Changizi is an Assistant Professor of Cognitive Science at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in New York and the author of The Vision Revolution and The Brain From 25,000 Feet. More of Dr. Changizi’s writing can be found on his blog, Facebook Fan Page, and Twitter.

ScriptPhD.com was privileged to sit down with Dr. Changizi for a half-hour interview about the concepts behind his current book, The Vision Revolution, out in paperback June 10, the magic that is human ocular perception, and their applications in our modern world. Listen to the podcast below:

~*ScriptPhD*~

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology

in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development.

Follow us on Twitter and our Facebook fan page. Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

]]>