The last 25 years have brought an unprecedented level of scientific and technological advances, impacting virtually all dimensions of society, from communication and the digital revolution, to economics and food production to nanotechnology and medicine – and that’s just a start. The next few decades will rapidly expand this progress with exponential discovery and innovation, amidst more pressing global challenges than we’ve ever faced before. The opportunities to develop faster, better and cheaper products that improve modern living are limitless – Tesla electric cars, energy-saving fuels and machines, robotics – but they all share a common basic need for developing and studying materials in a more efficient manner. This will require a real-time acceleration of sharing, analytics and simulation through readily accessible databases. Essentially, an open-source wiki for materials scientists. In our in-depth article below, ScriptPhD.com explains why materials science is the most critical gateway towards 21st Century technology and how California startup company Citrine Informatics is providing revolutionary new information extraction software to create a crowdsourced, open access database available to any scientist.

There has been a public access revolution of sorts transforming science. A necessary one, at that. Science funding is in crisis. The peer-review process is under heavy scrutiny. And scientists are turning to transparency to help. Some notable billionaires are circumventing public funding and privatizing science. Molecular biologist Ethan Perlstein has used crowdfunding to raise hundreds of thousands of dollars from the public at large for a basic research lab. Last fall, as the Ebola crisis gripped the world’s attention, an expert researcher at The Scripps Research Institute (where I received a PhD) appealed to public crowd funding to raise $100,000 for vaccine research. With platforms like Experiment, RocketHub and KickStarter proliferating support for science, the public at large has begun to serve as an important incubator of innovation. More importantly, researchers are increasingly rethinking traditional academic publishing and recognizing the value of open data sharing through publications and databases. The Public Library of Science (PLoS) is the biggest non-profit advocate and publisher of open access research. Mainstream journals like Science have begun publishing free web-based alternatives that are immediately accessible. Calls for unified data sharing have grown louder and more widespread. Even the FDA has announced plans for crowdsourcing a genomics research platform to improve efficiency of diagnostic and clinical tests and their analysis. Far from hindering the scientific process and output, these efforts have accelerated alternative means of funding, data acquisition and exchange, collaboration and ultimately, discovery.

Think about virtually any practical aspect of life and it relies on materials. Transportation of any kind, Kevlar vests, sports equipment, communication devices, clothing, growing and making food… it’s impossible to think about modern society in even the most impoverished developing countries without them. Now think on a bigger scale. Superconductors. Carbon nanotubules. Graphene. The materials of the future that make even these breakthroughs obsolete. So crucial is materials science to all facets of economics, research and quality of life, that in 2011, the United States Government launched a Materials Genome Initiative. A partnership between the private sector industry, universities, and the government, its primary goal is to utilize a materials genome approach to cut the cost and time to market for basic materials products by 50%.

The only problem with materials research? Data. And lots of it. Aided largely by digital services and a proliferation of technology research – not to mention marketplace for the products that it makes possible – there is so much data produced today that the process of testing, developing, tweaking and inserting a material into a product takes about 20 years, according to the National Academy of Sciences. To combat this, materials scientists and engineers have growingly embraced a similar open access philosophy to that of life scientists. Leading science publisher Elsevier recently launched an infrastructure called “Open Data” to facilitate materials science data sharing across thirteen major publications. The Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory just created the world’s largest database of elastic properties, a virtual gold mine for scientists working on materials that require mechanical properties for things like cars and airplanes. NASA has even opened a Physical Science Informatics database of all of its space station materials research in the hopes that the crowdsourcing accelerates engineering research discovery, applicable both to space and Earth.

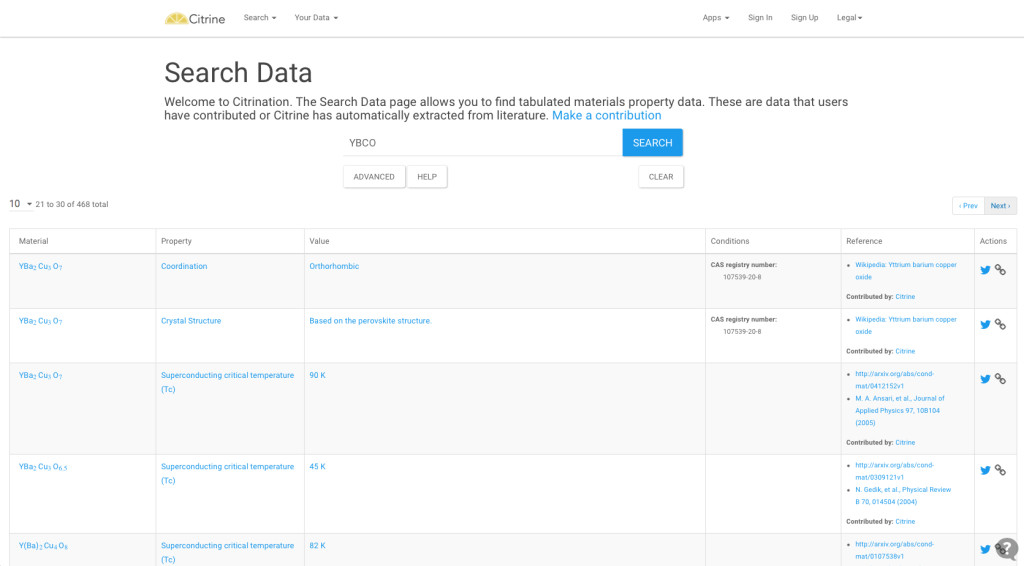

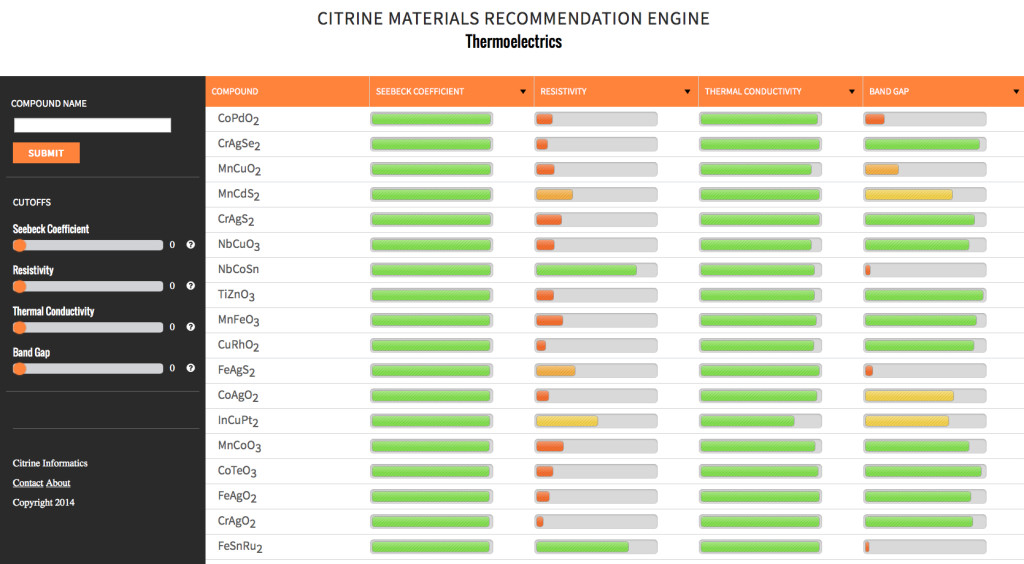

Citrine Informatics, a startup company in California, is hoping to unify these concepts of data sharing and mining through open access web-based software (boosted by crowdsourcing) to build a comprehensive, open database of materials and chemical data. Essentially, Citrine is rolling out a cloud platform (Citrination) that will act as a digital middle man between data acquisition and product development. And rather than storing it in vastly differing locations under differing access guidelines, Citrination’s algorithms gather all available data (from publications to databases to publicly shared data from private companies) in order to show properties under different conditions, including when they might fail. A simple, mainframe registry database allows users to upload data, build customized data sets and see all known properties of a particular material under all different physical conditions (see below). Rater than testing and retesting internal materials data internally, thus lengthening R&D pipelines, research labs can simply model based on available information and adjust experiments accordingly.

“What we do represents a big change in the status quo,” co-founder Bryce Meredig says. “A lot of the scientists in these industries don’t have a natural inclination to turn to software to solve these problems.” Until now. The software will be made free to not for profit research institutions and will sell to materials and chemical companies that want to avail themselves of the wealth of data. Citrine has used a large recent infusion of grant funding to raise their ambition beyond a database and towards applications like 3D printing, renewable energy technology (co-founder Greg Mulholland was recognized by Forbes as a 30 under 30 leader in energy) and the next generation of devices.

The practical benefits to society as a whole of extending open access and crowdsourcing to materials science are tremendous. On an individual level, virtually every computer and mobile device we put in our hands, every gadget and machine we buy in the future will depend on improved materials. On a more wide-scale level, materials will be at the forefront of solving the most complex, important challenges to our planet and its inhabitants, none more important than the energy crisis. Food production, water purification and distribution, transportation, infrastructure all will rely on creating sustainable energy. More ambitious endeavors such as space travel, medical treatments and advanced research collaborations will be even more reliant on new and improved materials. The faster that scientists, researchers and engineers are able to mine data from previous experiments, replicate it and design smarter studies based on computerized algorithms of how those materials behave, the faster they can produce breakthroughs in the laboratory and into the marketplace. The stakes are high. The scientific rewards are infinite. The time to open and use a free-access materials database is now.

This article was sponsored by Citrine Informatics.

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development. Follow us on Twitter and Facebook. Subscribe to our podcast on SoundCloud or iTunes.