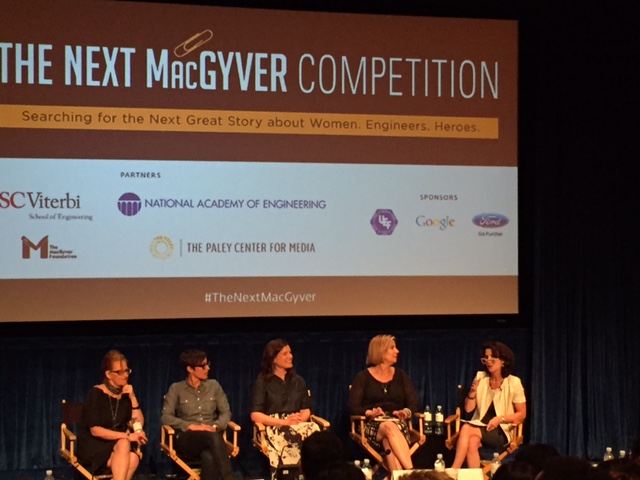

Engineering has an unfortunate image problem. With a seemingly endless array of socioeconomic, technological and large-scale problems to address, and with STEM fields set to comprise the most lucrative 21st Century careers, studying engineering should be a no-brainer. Unfortunately, attracting a wide array of students — or even appreciating engineers as cool — remains difficult, most noticeably among women. When Google Research found out that the #2 reason girls avoid studying STEM fields is perception and stereotypes on screen, they decided to work with Hollywood to change that. Recently, they partnered with the National Academy of Sciences and USC’s prestigious Viterbi School of Engineering to proactively seek out ideas for creating a television program that would showcase a female engineering hero to inspire a new generation of female engineers. The project, entitled “The Next MacGyver,” came to fruition last week in Los Angeles at a star-studded event. ScriptPhD.com was extremely fortunate to receive an invite and have the opportunity to interact with the leaders, scientists and Hollywood representatives that collaborated to make it all possible. Read our full comprehensive coverage below.

“We are in the most exciting era of engineering,” proclaims Yannis C. Yortsos, the Dean of USC’s Engineering School. “I look at engineering technology as leveraging phenomena for useful purposes.” These purposes have been recently unified as the 14 Grand Challenges of Engineering — everything from securing cyberspace to reverse engineering the brain to solving our environmental catastrophes to ensuring global access to food and water. These are monumental problems and they will require a full scale work force to fully realize. It’s no coincidence that STEM jobs are set to grow by 17% by 2024, more than any other sector. Recognizing this opportunity, the US Department of Education (in conjunction with the Science and Technology Council) launched a five-year strategic plan to prioritize STEM education and outreach in all communities.

Despite this golden age, where the possibilities for STEM innovation seem as vast as the challenges facing our world, there is a disconnect in maximizing a full array of talent for the next generation of engineers. There is a noticeable paucity of women and minority students studying STEM fields, with women comprising just 18-20% of all STEM bachelor’s degrees, regardless of the fact that more students are STEM degrees than ever before. Madeline Di Nono, CEO of the Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media and a judge at the Next MacGyver competition, boils a lot of the disinterest down to a consistent lack of female STEM portrayal in television and film. “It’s a 15:1 ratio of male to female characters for just STEM alone. And most of the science related positions are in life sciences. So we’re not showing females in computer science or mathematics, which is where all the jobs are going to be.” Media portrayals of women (and by proxy minorities) in science remains shallow, biased and appearance-focused (as profiled in-depth by Scientific American). Why does this matter? There is a direct correlation between positive media portrayal and STEM career participation.

It has been 30 years since the debut of television’s MacGyver, an action adventure series about clever agent Angus MacGyver, working to right the wrongs of the world through innovation. Rather than using a conventional weapon, MacGyver thwarts enemies with his vast array of scientific knowledge — sometimes possessing no more than a paper clip, a box of matches and a roll of duct tape. Creator Lee Zlotoff notes that in those 30 years, the show has run continuously around the world, perhaps fueled in part by a love of MacGyver’s endless ingenuity. Zlotoff noted the uncanny parallels between MacGyver’s thought process and the scientific method: “You look at what you have and you figure out, how do I turn what I have into what I need?” Three decades later, in the spirit of the show, the USC Viterbi School of Engineering partnered with the National Academy of Sciences and the MacGyver Foundation to search for a new MacGyver, a television show centered around a female protagonist engineer who must solve problems, create new opportunities and most importantly, save the day. It was an initiative that started back in 2008 at the National Academy of Sciences, aiming to rebrand engineering entirely, away from geeks and techno-gadget builders towards an emphasis on the much bigger impact that engineering technology has on the world – solving big, global societal problems. USC’s Yortsos says that this big picture resonates distinctly with female students who would otherwise be reluctant to choose engineering as a career. Out of thousands of submitted TV show ideas, twelve were chosen as finalists, each of whom was given five minutes to pitch to a distinguished panel of judges comprising of writers, producers, CEOs and successful show runners. Five winners will have an opportunity to pair with an established Hollywood mentor in writing a pilot and showcasing it for potential production for television.

If The Next MacGyver feels far-reaching in scope, it’s because it has aspirations that stretch beyond simply getting a clever TV show on air. No less than the White House lent its support to the initiative, with an encouraging video from Chief Technology Officer Megan Smith, reiterating the importance of STEM to the future of the 21st Century workforce. As Al Roming, the President of the National Academy of Engineering noted, the great 1950s and 1960s era of engineering growth was fueled by intense competition with the USSR. But we now need to be unified and driven by the 14 grand challenges of engineering and their offshoots. And part of that will include diversifying the engineering workforce and attracting new talent with fresh ideas. As I noted in a 2013 TEDx talk, television and film curry tremendous power and influence to fuel science passion. And the desire to marry engineering and television extends as far back as 1992, when Lockheed and Martin’s Norm Augustine proposed a high-profile show named LA Engineer. Since then, he has remained a passionate advocate for elevating engineers to the highest ranks of decision-making, governance and celebrity status. Andrew Viterbi, namesake of USC’s engineering school, echoed this imperative to elevate engineering to “celebrity status” in a 2012 Forbes editorial. “To me, the stakes seem sufficiently high,” said Adam Smith, Senior Manager of Communications and Marketing at USC’s Viterbi School of Engineering. “If you believe that we have real challenges in this country, whether it is cybersecurity, the drought here in California, making cheaper, more efficient solar energy, whatever it may be, if you believe that we can get by with half the talent in this country, that is great. But I believe, and the School believes, that we need a full creative potential to be tackling these big problems.”

So how does Hollywood feel about this movement and the realistic goal of increasing its array of STEM content? “From Script To Screen,” a panel discussion featuring leaders in the entertainment industry, gave equal parts cautionary advice and hopeful encouragement for aspiring writers and producers. Ann Merchant, the director of the Los Angeles-based Science And Entertainment Exchange, an offshoot of the National Academy of Sciences that connects filmmakers and writers with scientific expertise for accuracy, sees the biggest obstacle facing television depiction of scientists and engineers as a connectivity problem. Writers know so few scientists and engineers that they incorporate stereotypes in their writing or eschew the content altogether. Ann Blanchard, of the Creative Artists Agency, somewhat concurred, noting that writers are often so right-brain focused, that they naturally gravitate towards telling creative stories about creative people. But Danielle Feinberg, a computer engineer and lighting director for Oscar-winning Pixar animated films, sees these misconceptions about scientists and what they do as an illusion. When people find out that you can combine these careers with what you are naturally passionate about to solve real problems, it’s actually possible and exciting. Nevertheless, ABC Fmaily’s Marci Cooperstein, who oversaw and developed the crime drama Stitchers, centered around engineers and neuroscientists, remains optimistic and encouraged about keeping the doors open and encouraging these types of stories, because the demand for new and exciting content is very real. Among 42 scripted networks alone, with many more independent channels, she feels we should celebrate the diversity of science and medical programming that already exists, and build from it. Put together a room of writers and engineers, and they will find a way to tell cool stories.

At the end of the day, Hollywood is in the business of entertaining, telling stories that reflect the contemporary zeitgeist and filling a demand for the subjects that people are most passionate about. The challenge isn’t wanting it, but finding and showcasing it. The panel’s universal advice was to ultimately tell exciting new stories centered around science characters that feel new, flawed and interesting. Be innovative and think about why people are going to care about this character and storyline enough to come back each week for more and incorporate a central engine that will drive the show over several seasons. “Story does trump science,” Merchant pointed out. “But science does drive story.”

The twelve pitches represented a diverse array of procedural, adventure and sci-fi plots, with writers representing an array of traditional screenwriting and scientific training. The five winners, as chosen by the judges and mentors, were as follows:

Miranda Sajdak — Riveting

Sajdak is an accomplished film and TV writer/producer and founder of screenwriting service company ScriptChix. She proposed a World War II-era adventure drama centered around engineer Junie Duncan, who joins the military engineer corps after her fiancee is tragically killed on the front line. Her ingenuity and help in tackling engineering and technology development helps ultimately win the war.

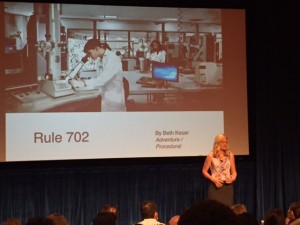

Beth Keser, PhD — Rule 702

Dr. Keser, unique among the winners for being the only pure scientist, is a global leader in the semiconductor industry and leads a technology initiative at San Diego’s Qualcomm. She proposed a crime procedural centered around Mimi, a brilliant scientist with dual PhDs, who forgoes corporate life to be a traveling expert witness for the most complex criminal cases in the world, each of which needs to be investigated and uncovered.

Jayde Lovell — SECs (Science And Engineering Clubs)

Jayde, a rising STEM communication star, launched the YouTube pop science network “Did Someone Say Science?.” Her show proposal is a fun fish-out-of-water drama about 15-year-old Emily, a pretty, popular and privileged high school student. After accidentally burning down her high school gym, she forgoes expulsion only by joining the dreaded, geeky SECs club, and in turn, helping them to win an engineering competition while learning to be cool.

Craig Motlong — Q Branch

Craig is a USC-trained MFA screenwriter and now a creative director at a Seattle advertising agency. His spy action thriller centered around mad scientist Skyler Towne, an engineer leading a corps of researchers at the fringes of the CIA’s “Q Branch,” where they develop and test the gadgets that will help agents stay three steps ahead of the biggest criminals in the world.

Shanee Edwards — Ada and the Machine

Shanee, an award-winning screenwriter, is the film reviewer at SheKnows.com and the host/producer of the web series She Blinded Me With Science. As a fan of traditional scientific figures, Shanee proposed a fictionalized series around real-life 1800s mathematician Ada Lovelace, famous for her work on Charles Babbage’s early mechanical general-purpose computer, the Analytical Engine. In this drama, Ada works with Babbinge to help Scotland Yard fight opponents of the industrial revolution, exploring familiar themes of technology ethics relevant to our lives today.

Craig Motlong, one of five ultimate winners, and one of the few finalists with absolutely no science background, spent several months researching his concept with engineers and CIA experts to see how theoretical technology might be incorporated and utilized in a modern criminal lab. He told me he was equal parts grateful and overwhelmed. “It’s an amazing group of pitches, and seeing everyone pitch their ideas today made me fall in love with each one of them a little bit, so I know it’s gotta be hard to choose from them.”

Whether inspired by social change, pragmatic inquisitiveness or pure scientific ambition, this seminal event was ultimately both a cornerstone for strengthening a growing science/entertainment alliance and a deeply personal quest for all involved. “I don’t know if I was as wrapped up in these issues until I had kids,” said USC’s Smith. “I’ve got two little girls, and I tried thinking about what kind of shows [depicting female science protagonists] I should have them watch. There’s not a lot that I feel really good sharing with them, once you start scanning through the channels.” Motlong, the only male winner, is profoundly influenced by his experience of being surrounded by strong women, including a beloved USC screenwriting instructor. “My grandmother worked during the Depression and had to quit because her husband got a job. My mom had like a couple of options available to her in terms of career, my wife wanted to be a genetic engineer when she was little and can’t remember why she stopped,” he reflected. “So I feel like we are losing generations of talent here, and I’m on the side of the angels, I hope.” NAS’s Ann Merchant sees an overarching vision on an institutional level to help achieve the STEM goals set forth by this competition in influencing the next generation of scientist. “it’s why the National Academy of Sciences and Engineering as an institution has a program [The Science and Entertainment Exchange] based out of Los Angeles, because it is much more than this [single competition].”

Indeed, The Next MacGyver event, while glitzy and glamorous in a way befitting the entertainment industry, still seemed to have succeeded wildly beyond its sponsors’ collective expectations. It was ambitious, sweeping, the first of its kind and required the collaboration of many academic, industry and entertainment alliances. But it might have the power to influence and transform an entire pool of STEM participants, the way ER and CSI transformed renewed interest in emergency medicine and forensic science and justice, respectively. If not this group of pitched shows, then the next. If not this group of writers, then the ones who come after them. Searching for a new MacGyver transcends finding an engineering hero for a new age with new, complex problems. It’s about being a catalyst for meaningful academic change and creative inspiration. Or at the very least opening up Hollywood’s eyes and time slots. Zlotoff, whose MacGyver Foundation supported the event and continually seeks to promote innovation and peaceful change through education opportunities, recognized this in his powerful closing remarks. “The important thing about this competition is that we had this competition. The bell got rung. Women need to be a part of the solution to fixing the problems on this planet. [By recognizing that], we’ve succeeded. We’ve already won.”

The Next MacGyver event was held at the Paley Center For Media in Beverly Hills, CA on July 28, 2015. Follow all of the competition information on their site. Watch a full recap of the event on the Paley Center YouTube Channel.

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development. Follow us on Twitter and Facebook. Subscribe to our podcast on SoundCloud or iTunes.

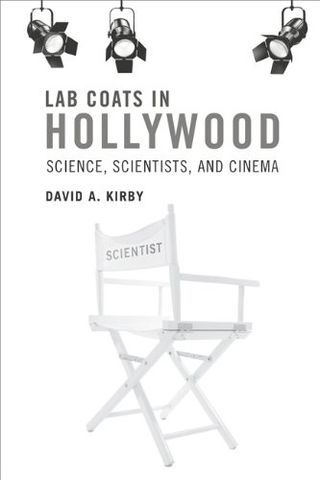

Read through any archive of science fiction movies, and you quickly realize that the merger of pop culture and science dates as far back as the dawn of cinema in the early 1920s. Even more surprising than the enduring prevalence of science in film is that the relationship between film directors, scribes and the science advisors that have influenced their works is equally as rich and timeless. Lab Coats in Hollywood: Science, Scientists, and Cinema (2011, MIT Press), one of the most in-depth books on the intersection of science and Hollywood to date, serves as the backdrop for recounting the history of science and technology in film, how it influenced real-world research and the scientists that contributed their ideas to improve the cinematic realism of science and scientists. For a full ScriptPhD.com review and in-depth extended discussion of science advising in the film industry, please click the “continue reading” cut.

Written by David A. Kirby, Lecturer in Science Communication Studies at the Centre for History of Science, Technology and Medicine at the University of Manchester, England, Lab Coats offers a surprising, detailed analysis of the symbiotic—if sometimes contentious—partnership between filmmakers and scientists. This includes the wide-ranging services science advisors can be asked to provide to members of a film’s production staff, how these ideas are subsequently incorporated into the film, and why the depiction of scientists in film carries such enormous real-world consequences. Thorough, detailed, and honest, Lab Coats in Hollywood is an exhaustive tome of the history of scientists’ impact on cinema and storytelling. It’s also an essential and realistic road map of the challenges that scientists, engineers and other technical advisors might face as they seriously pursue science advising to the film industry as a career.

The essential questions that Lab Coats in Hollywood addresses are these—is it worth it to hire a science advisor for a movie production? Is it worth it for the scientist to be an advisor? The book’s purposefully vague conclusion is that it depends solely on how the scientist can film’s storyline and visual effects. Kirby wisely writes with an objective tone here because the topic is open to a considerable amount of debate among the scientists and filmmakers profiled in the book. Sometimes a scientist is so key to a film’s development, he or she becomes an indispensible part of the day-to-day production. A good example of this is Jack Horner, paleontologist at the Museum of the Rockies in Bozeman, MT, and technical science advisor to Steven Spielberg in Jurassic Park and both of its sequels. Horner, who drew from his own research on the link between dinosaurs and birds for a more realistic depiction of the film’s contentious science, helped filmmakers construct visuals, write dialogue, character reactions, animal behaviors, and map out entire scenes. J. Marvin Herndon, a geophysicist at the Transdyne Corporation, approached the director of the disaster film The Core when he learned the plot was going to be based on his controversial hypothesis about a giant uranium ball in the center of the Earth. Herndon’s ideas were fully incorporated into the film’s plot, while Herndon rode the wave of publicity from the film to publish his research in a PNAS paper. The gold standard of science input, however, were Stanley Kubrik’s multiple science and engineering advisors for 2001: A Space Odyssey, discussed in much further detail below.

Kirby hypothesizes that sometimes, a film’s poor reception might have been avoided with a science advisor. He provides the example of the Arnold Schwarzenegger futuristic sci-fi bomb The Sixth Day, which contained a ludicrously implausible use of human cloning in its main plot. While the film may have been destined for failure, Kirby posits that it only could have benefited from proper script vetting by a scientist. By contrast, the 1998 action adventure thriller Armageddon came under heavy expert criticism for its basic assertion that an asteroid “the size of Texas” could go undetected until eighteen days before impact. Director Michael Bay patently refused to take the advice of his advisor, NASA researcher Ivan Bakey, and admitted he was sacrificing science for plot, but Armageddon went on to be a huge box office hit regardless. Quite often, the presence of a science advisor is helpful, albeit unnecessary. One of the book’s more amusing anecdotes is about Dustin Hoffman’s hyper-obsessive shadowing of a scientist for the making of the pandemic thriller Outbreak (great guide to the movie’s science can be found here). Hoffman was preparing to play a virologist and wanted to infuse realism in all of his character’s reactions. Hoffman kept asking the scientist to document reactions in mundane situations that we all encounter—a traffic jam, for example—only to come to the shocking conclusion that the scientist was a real person just like everyone else.

Most of the time, including scientists in the filmmaking process is at the discretion of the studios because of the one immutable decree reiterated throughout the book: the story is king. When a writer, producer or director hires a science consultant, their expertise is utilized solely to facilitate, improve or augment story elements for the purposes of entertaining the audience. Because of this, one of the most difficult adjustments a science consultant may face is a secondary status on-set even though they may be a superstar in their own field. Some of the other less glamorous aspects of film consulting include heavy negotiations with unionized writers for script or storyline changes, long working hours, a delicate balance between side consulting work and a day job, and most importantly, an inconsistent (sometimes nonexistent) payment structure per project. I was notably thrilled to see Kirby mention the pros and cons of programs such as the National Science Foundation’s Creative Science Studio (a collaboration with USC’s school of the Cinematic Arts) and the National Academy of Science’s Science and Entertainment Exchange, which both provide on-demand scientific expertise to the Hollywood filmmaking community in the hope of increasing and promoting the realism of scientific portrayal in film. While valuable commodities to science communication, both programs have had the unfortunate effect of acclimating Hollywood studios to expect high-level scientific consulting for free.

1968’s 2001: A Space Odyssey is widely considered by popular consensus to be the greatest sci-fi movie ever made, and certainly the most influential. As such, Kirby devotes an entire chapter to detailing the film’s production and integration of science. Director Stanley Kubrik took painstaking detail in scientific accuracy to explore complex ideas about the relationship between humanity and technology, hiring a range of advisors from anthropologists, aeronautical engineers, statisticians, and nuclear physicists for various stages of production. Statistician I. J. Good provided advice on supercomputers, aerospace Harry Lange provided production design, while NASA space scientist Frederick Ordway lent over three years of his time to develop the space technology used in the film. In doing so, Kubrik’s staff consulted with over sixty-five different private companies, government agencies, university groups and research institutions. So real was the space technology in 2001 that moon landing hoax supporters have claimed the real moon landing by United States astronauts, taking place in 1969, was taped on the same sets. Not every science-based film has used science input as meticulously or thoroughly since, but Kubrik’s influence on the film industry’s fascination with science and technology has been an undeniable legacy.

One of the real treats of Lab Coats in Hollywood is the exploration of the two-way relationship between scientists and filmmakers, and how film in turn influences the course of science, as we discuss in more detail below. Between film case studies, critiques and interviews with past science advisors are interstitial vignettes of ways scientists have shaped films we know and love. Even the animated feature Finding Nemo had an oceanography advisor to get the marine biology correct. The seminal moment of the most recent Star Trek installation was due to a piece of off-handed scientific advice from an astronomer. The cloning science of Jurassic Park, so thoroughly researched and pieced together by director Steven Spielberg and science advisor Jack Horner, was actually published in a top-notch journal days ahead of the movie’s premiere. Even in rare spots where the book drags a bit with highly technical analysis are cinematic backstories with details that readers will salivate over. (For example, there’s a very good reason all the kelp went missing from Finding Nemo between its cinematic and DVD releases.)

As the director of a creative scientific consulting company based in Los Angeles, one of the biggest questions I get asked on a regular basis is “What does a science advisor do, exactly?” Lab Coats in Hollywood does an excellent job of recounting stories and case studies of high-profile scientist consultants, all of whom contributed their creative talents to their respective films in different ways, what might be expected (and not expected) of scientists on set, and of giving different areas of expertise that are currently in demand in Hollywood. Kirby breaks down cinematic fact checking, the most frequent task scientists are hired to perform, into three areas within textbook science (known, proven facts that cannot be disputed, such as gravity): public science, something we all know and would think was ridiculous if filmmakers got wrong, expert science, facts that are known to specialists and scientific experts outside of the lay audience, and (most problematic) folk science, incorrect science that has nevertheless been accepted as true by the public. Filmmakers are most likely to alter or modify facts that they perceive as expert science to minimize repercussions at the box office.

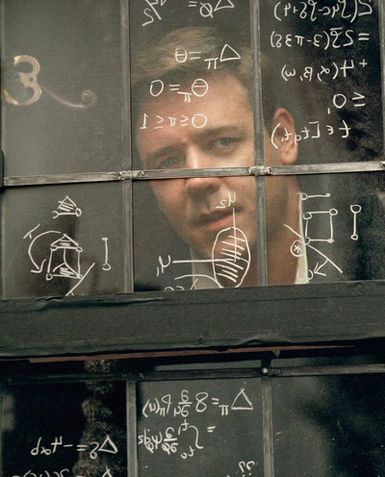

A science advisor is constantly navigating cinematic storytelling constraints and a filmmaker’s desire to utilize only the most visually appealing and interesting aspects of science (regardless of whether the context is always academically appropriate). Another broad area of high demand is in helping actors look and act like a real scientist on screen. Scientists have been hired to do everything from doctoring dialogue to add realism into an actor’s portrayal (the movie Contact and Jodie Foster’s depiction of Dr. Ellie Arroway is a good example of this), training actors in using equipment and pronouncing foreign-sounding jargon, replicating laboratory notebooks or chalkboard scribbles with the symbols and shorthand of science (such as in the mathematics film A Beautiful Mind), and to recreate the physical space of an authentic laboratory. Finally, the scientist’s expertise of the known is used to help construct plausible scenarios and storylines for the speculative, an area that requires the greatest degree of flexibility and compromise from the science advisor. Uncertainty, unexplored research and “what if” scenarios, the bane of every scientist’s existence, happen to be Hollywood’s favorite scenarios, because they allow the greatest creative freedom in storytelling and speculative conceptualization without being negated by a proven scientific impossibility. An entire chapter—the book’s finest—is devoted to two case studies, Deep Impact and The Hulk, where real science concepts (near-Earth asteroid impacts and genetic engineering, respectively) were researched and integrated into the stories that unfolded in the films. (Side note: if you are ever planning on being a science advisor read this section of the book very carefully).

In years past, consulting in films didn’t necessarily bring acclaim to scientists within their own research communities; indeed, Lab Coats recounts many instances where scientists were viewed as betraying science or undermining its seriousness with Hollywood frivolity, including many popular media figures such as Carl Sagan and Paul Ehrlich. Recently, however, consultants have come to be viewed as publicity investments both by studios that hire high-profile researchers for recognition value of their film’s science content and by institutes that benefit from branding and exposure. Science films from the last 10-15 years such as GATTACA, Outbreak, Armageddon, Contact, The Day After Tomorrow and a panoply of space-related flicks have attached big-name scientists as consultants (gene therapy pioneer French Anderson, epidemiologist David Morens, NASA director Ivan Bekey, SETI institute astronomers Seth Shostak and Jill Tartar and climatologist Michael Molitor, respectively). They also happened to revolve around the research salient to our modern era: genetic bioengineering, global infectious diseases, near-earth objects, global warming and (as always) exploring deep space. As such, a mutually beneficial marketing relationship has emerged between science advisors and studios that transcends the film itself resulting in funding and visibility to individual scientists, their research, and even institutes and research centers. The National Severe Storms Laboratory (NSSL) promoted themselves in two recent films, Twister and Dante’s Peak, using the films as a vehicle to promote their scientific work, to brand themselves as heroes underfunded by the government, and to temper public expectations about storm predictions. No institute has had a deeper relationship with Hollywood than NASA, extending back to the Star Trek television series, with intricate involvement and prominent logo display in the films Apollo 13, Armageddon, Mission to Mars, and Space Cowboys. Some critics have argued that this relationship played an integral role in helping NASA maintain a positive public profile after the devastating 1986 Challenger space shuttle disaster. The end result of the aforementioned promotion via cinematic integration can only benefit scientific innovation and public support.

Accurate and favorable portrayal of science content in modern cinema has an even bigger beneficiary than specific research institutes, and that is society itself. Fictional technology portrayed in film – termed a “diegetic prototype” – has often inspired or led directly to real-world application and development. Kirby offers the most impactful case of diegetic prototyping as the 1981 film Threshold, which portrayed the first successful implantation of a permanent artificial heart, a medical marvel that became reality only a year later. Robert Jarvik, inventor of the Jarvik-7 artificial heart used in the transplant, was also a key medical advisor for Threshold, and felt that his participation in the film could both facilitate technological realism and by doing so, help ease public fears about what was then considered a freak surgery, even engendering a ban in Great Britain. Of the many obstacles that expensive, ambitious, large-scale research faces, Kirby argues that skepticism or lack of enthusiasm from the public can be the most difficult to overcome, precisely because it feeds directly into essential political support that makes funding possible. A later example of film as an avenue for promotion of futuristic technology is Minority Report, set in the year 2054, and featuring realistic gestural interfacing technology and visual analytics software used to predict crime before it actually happens. Less than a decade later, technology and gadgets featured in the film have come to fruition in the form of multi-touch interfaces like the iPad and retina scanners, with others in development including insect robots (mimics of the film’s spider robots), facial recognition advertising billboards, crime prediction software and electronic paper. A much more recent example not featured in the book is the 2011 film Limitless, featuring a writer that is able to stimulate and access 100% of his brain at will by taking a nootropic drug. While the fictitious drug portrayed in the film is not yet a neurochemical reality, brain enhancement is a rising field of biomedical research, and may one day indeed yield a brain-boosting pill.

No other scientific feat has been a bigger beneficiary of diegetic prototyping than space travel, starting with 1929’s prophetic masterpiece Frau im Mond [Woman in the Moon], sponsored by the German Rocket Society and advised masterfully by Hermann Oberth, a pioneering German rocket research scientist. The first film to ever present the basics of rocket travel in cinema, and credited with the now-standard countdown to zero before launch in real life, Frau im Mond also featured a prototype of the liquid-fuel rocket and inspired a generation of physicists to contribute to the eventual realization of space travel. Destination Moon, a 1950 American sci-fi film about a privately financed trip to the Moon, was the first film produced in the United States to deal realistically with the prospect of space travel by utilizing the technical and screenplay input of notable science fiction author Robert A. Heinlein. Released seven years before the start of the USSR Sputnik program, Destination Moon set off a wave of iconic space films and television shows such as When Worlds Collide, Red Planet Mars, Conquest of Space and Star Trek in the midst of the 1950s and 1960s Cold War “space race” between the United States and Russia. What theoretical scientific feat will propel the next diegetic prototype? A mission to Mars? Space colonization? Anti-aging research? Advanced stem cell research? Time will only tell.

Ultimately, readers will enjoy Lab Coats in Hollywood for its engaging writing style, detailed exploration of the history of science in film and most of all, valuable advice from fellow scientists who transitioned from the lab to consulting on a movie set. Whether you are a sci-fi film buff or a research scientist aspiring to be a Hollywood consultant, you will find some aspect of this book fascinating. Especially given the rapid proliferation of science and technology content in movies (even those outside of the traditional sci-fi genre), and the input from the scientific community that it will surely necessitate, knowing the benefits and pitfalls of this increasingly in-demand career choice is as important as its significance in ensuring accurate portrayal of scientists to the general public.

~*ScriptPhD*~

***************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development.

Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

]]>