On February 28, 1998, the revered British medical journal The Lancet published a brief paper by then-high profile but controversial gastroenterologist Andrew Wakefield that claimed to have linked the MMR (measles, mumps and rubella) vaccine with regressive autism and inflammation of the colon in a small case number of children. A subsequent paper published four years later claimed to have isolated the strain of attenuated measles virus used in the MMR vaccine in the colons of autistic children through a polymerase chain reaction (PCR amplification). The effect on vaccination rates in the UK was immediate, with MMR vaccinations reaching a record low in 2003/2004, and parts of London losing herd immunity with vaccination rates of 62%. 15 American states currently have immunization rates below the recommended 90% threshold. Wakefield was eventually exposed as a scientific fraud and an opportunist trying to cash in on people’s fears with ‘alternative clinics’ and pre-planned a ‘safe’ vaccine of his own before the Lancet paper was ever published. Even the 12 children in his study turned out to have been selectively referred by parents convinced of a link between the MMR vaccine and their children’s autism. The original Lancet paper was retracted and Wakefield was stripped of his medical license. By that point, irreparable damage had been done that may take decades to reverse.

How could a single fraudulent scientific paper, unable to be replicated or validated by the medical community, cause such widespread panic? How could it influence legions of otherwise rational parents to not vaccinate their children against devastating, preventable diseases, at a cost of millions of dollars in treatment and worse yet, unnecessary child fatalities? And why, despite all evidence to the contrary, have people remained adamant in their beliefs that vaccines are responsible for harming otherwise healthy children, whether through autism or other insidious side effects? In his brilliant, timely, meticulously-researched book The Panic Virus, author Seth Mnookin disseminates the aggregate effect of media coverage, echo chamber information exchange, cognitive biases and the desperate anguish of autism parents as fuel for the recent anti-vaccine movement. In doing so, he retraces the triumphs and missteps in the history of vaccines, examines the social impact of rejecting the scientific method in a more broad perspective, and ways that this current utterly preventable public health crisis can be avoided in future scenarios. A review of The Panic Virus, an enthusiastic ScriptPhD.com Editor’s Selection, follows below.

Such fervent controversy over inoculating young children for communicable diseases might have seemed unimaginable to the pre-vaccine generations. It wasn’t long ago, Mnookin chronicles, that death and suffering at the hands of diseases like polio and small pox were the accepted norm. In 18th Century Europe, for example, 400,000 people per year regularly died of small pox, and it caused one third of all cases of blindness. So desperate were people to avoid the illnesses’ ravages, that crude, rudimentary inoculation methods were employed, even at the high risk of death, to achieve life-long immunity. A 1916 polio outbreak in New York City, with fatality rates between 20 and 25 percent, frayed nerves and public health infrastructure to the point of near-anarchy. As the disease waxed and waned in outbreaks throughout the decades that followed, distraught parents had no idea about how to protect their children, who were often far more susceptible to fatality than adults. By the time Jonas Salk’s polio vaccine breakthrough was announced as “safe, effective and potent” on April 12, 1955, pandemonium broke out. “Air raid sirens were set off,” Mnookin writes. “Traffic lights blinked red; churches’ bells rang; grown men and women wept; schoolchildren observed a moment of silence.” Salk’s discovery was hailed as “one of the greatest events in the history of medicine.”

Mnookin doesn’t let scientists off the hook where vaccines are concerned, however, and rightfully so. Starting around World War II, with advances such as the cowpox and polio vaccines, along with the dawning of the Antibiotics Age, eradicating death and suffering from communicable diseases and bacterial infections, a hubris and sense of superiority began to creep into the scientific establishment, with dangerous consequences. Fearing the threat of biological warfare during World War II, a 1941 hastily-constructed US military campaign to vaccinate all US troops against yellow fever resulted in batches contaminated with Hepatitis B, resulting in 300,000 infections and 60 deaths. The first iteration of Salk’s polio vaccine was only 60-90% effective before being perfected and eventually replaced by the more effective Sabin vaccine. Furthermore, dozens of children who had received doses from the first batch of vaccines were paralyzed or killed due to contaminated vaccines that had failed safety tests. In 1976, buoyed by the death of a soldier from a flu virus that bore striking genetic similarity to the 1918 Spanish flu epidemic strain, President Gerald Ford instituted a nation-wide mass vaccination initiative against a “swine flu” epidemic. Unfortunately, although 40 million Americans were vaccinated in three months, 500 developed symptoms of Guillain-Barré syndrome (30 died), seven times higher than would normally be expected as a rare side effect of vaccination. Many people feel that the scars of the 1976 fiasco have incurred a permanent distrust of the medical establishment and have haunted public health influenza immunization efforts to this day.

These black marks on the otherwise miraculous, life-saving history of vaccine development not only instilled a gradual mistrust in public health officials, but laid the groundwork for the incendiary autism-vaccine scandal. The only missing components were a proper context of panic, a snake oil salesman and a compliant media willing to spread his erroneous message.

Enter the autism epidemic and Andrew Wakefield’s hoax. Because this seminal event had such a profound effect on the formation and proliferation of the current anti-vaccine movement, it is chronicled in far greater detail than our introduction above. From precursor incidents that ripened the potential for coercion to the Wakefield’s shoddy methodology and the naive medical community that took him at his word, Mnookin weaves through this case with well-researched scientific facts, interesting interviews and logic. A large chunk of the book is ultimately devoted to the psychology of what the anti-vaccine movement really is: a cognitive bias and a willingness to stay adamant in the belief that vaccines cause harm despite all evidence to the contrary. “If you assume,” he writes, “as I had, that human beings are fundamentally logical creatures, this obsessive preoccupation with a theory that has for all intents and purposes been disproved is hard to fathom. But when it comes to decisions around emotionally charged topics, logic often takes a back seat to a set of unconscious mechanisms that convince us that it is our feelings about a situation and not the facts that represent the truth.”

Given this blog’s objective to cover science and technology in entertainment and media, it would be disingenuous to write about the anti-vaccine movement without recognizing the implicit role played by the media and entertainment industries in exacerbating the polemic. By lending a voice to the anti-vaccine argument, even in a subtle manner or in a journalistic attempt to “be fair to the other side,” over time, an echo chamber of lies turned into an inferno. In 1982, an hour-long NBC documentary called DPT: Vaccine Roulette aired, overemphasizing rare side effects in babies from vaccinations to a nation of alarmed parents and completely undermining their benefits. It was a propaganda piece, but an important hallmark for what would come later. A 2008 episode of the popular ABC hit show Eli Stone irresponsibly aired anti-vaccination propaganda involving a lawyer questioning a pharmaceutical company that manufactures vaccines due to the even then-debunked link to autism. For several recent years, actress and Playboy bunny Jenny McCarthy (who is given an entire chapter by Mnookin) became a tireless advocate against vaccinations, believing that they gave her son autism. She didn’t have any scientific proof for this, but was nevertheless given a platform by everyone from Larry King on CNN to a fawning Oprah Winfrey.

As it turns out, McCarthy’s son never even had autism, but rather a very rare and treatable neurological disorder. In a self-penned editorial for the Chicago Sun-Times, she has officially retroactively denied her anti-vaccine stance, and says she simply wants “more research on their effectiveness.” An extremely sympathetic 2014 eight-page Washington Post magazine article profile of prominent anti-vaccine activist Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. (who believes in the link between vaccines and autism) repeated his talking points numerous times throughout. This, among an endless cycle of interviews and appearances by defiant anti-vaccine proponents, given equal air time side-by-side with frustrated scientists, as if both positions were somehow viable, and worthy of journalistic debate. Once the worm was out of the can, no amount of rational discourse could temper the visceral antipathy that had been created. This is irresponsible, dangerous and flat-out wrong. When the public is confused about an esoteric issue pertaining to science, medicine or technology, influencers in the public eye cannot perpetuate misinformation.

Despite the unanimous medical repudiation of Wakefield’s fraudulent methods and conclusions and the retraction of his Lancet paper, an irreversible and insidious myth had begun permeating, first among the autism community, then spreading to proponents of organic and holistic approaches to health and finally, to mainstream society. In the aftermath of the controversy, epidemiological studies debunking the autism-vaccination “link,” combined with a growing disease crisis, have forced the largest US-based autism advocacy organization to reverse its stance and fully endorse vaccination to a still-divided community. Wakefield remains more defiant than ever, insisting to this day that his research was valid, attempting to sue the British journalism outlet that funded the inquiry into his fraud and peddling holistic treatments for autism as well as his “alternative” vaccine. Sadly, the public health ramifications have nothing short of disastrous, with a dangerous recurrence of several major childhood diseases.

A few examples of the many systemic casualties of the anti-vaccination movement (many occurring just since the publication of Mnookin’s book):

•A summary from the American Medical Association about the nascence of the measles crisis in 2011, when the US saw more measles cases than it had in 15 years

•Immunization rates falling so low that schools in some communities are being forced to terminate personal exemption waivers and, in some cases, legally mandated immunization for public school attendance

•California’s worst whooping cough epidemic in 70 years.

•Most recently, a measles outbreak at Disneyland, resulting in 26 cases spread across four states, after an unvaccinated woman visited the theme park

•Anti-vaccine hysteria has spread to Europe, which has had a measles rise of 348% from 2013 to 2014 (and growing), along with an alarming resurgence of pertussis

The scientific evidence that vaccines work is indisputable, and as the below infographic summarizes, their impact on morbidity from communicable diseases is miraculous. Sadly, now that the anti-vaccine movement has streamlined into the general population, anxious parents are conflicted as to whether vaccinating is the right choice for their children. We must start by going back to the basics of what a vaccine actually is and how it works. Next, we must reiterate the critical importance that maintaining herd immunity above 92-95% plays in protecting not only those too young or immunocompromised to be vaccinated, but even fully vaccinated populations. If all else fails, try emailing skeptical friends and family a clever graphic cartoon that breaks down digestible vaccine facts. Simply put: getting vaccinated is not a personal choice, it’s a selfish and dangerous choice.

The Panic Virus is first and foremost an incredibly entertaining, well-written narrative of the dawn of an anti-vaccine phenomenon which has reached a critical mass. It is also an important case study and cautionary tale about how we process and disseminate information in the age of the Internet and access to instant information. It is also an indictment on a trigger-happy, ratings-driven, sensationalist media that reports “news” as they interpret it first, and bother to check for facts later. In the case of the anti-vaccine movement of the last few years, the media fueled the fire that Andrew Wakefield started, and once a gaggle of angry, sympathetic parents was released, it was difficult (if-near impossible) to undo the damage. This type of journalism, Mnookin writes, “gives credence to the belief that we can intuit our way through all the various decisions we need to make in our lives and it validates the notion that our feelings are a more reliable barometer of reality than the facts.” Sadly, the autism-vaccine panic movement is not an outlying incident, but rather a disconcerting emblem of a growing anti-science agenda. The UN just released its most dire and alarming report ever issued on man-made climate change impacts, warning that temperature changes and industrial pollution will affect not just the environment, extreme weather events and coastal cities, but even the stability of our global economy itself. Immediate rebuttals from an influential lobbying group tried to undermine the majority of the scientists’ findings. So toxic is the corporate and political resistance to any kind of mitigating action, that some feel we need a technological or political miracle to stave off a certain environmental crisis. At a time when physicists are serious debate on evolution versus creationism and thousands of public schools across the United States use taxpayer funds to teach creationism in the classroom.

Mnookin’s book is an important resource and conversation starter for scientists, researchers and frustrated physicians as they carve out talking points and communication strategies to establish a dialogue with the public at large. When young parents have questions about vaccines (no matter how erroneous or ill-informed), pediatricians should already have materials for engaging in a positive, thoughtful discussion with them. When scientists and researchers encounter anti-science proclivities or subversive efforts to undermine their advocacy for a pressing issue, they should be armed with powerful, articulate communicators — ready and willing to deliberate in the media and convey factual information in an accessible way. When Jenny McCarthy and a gaggle of new-age holistic herbologists were peddling their “mommy instincts” and conspiracy theories against vaccines, far too many scientists and physicians simply thought it was beneath them to even engage in a discussion about something whose certainty and proof of concept was beyond reproach. Now, the newest polling suggests that nothing will change an anti-vaxxer’s mind, not even factual reasoning. Going forward, regardless of the issue at hand, this type of response can never happen again. The cost of complacency or arrogance is nothing short of life or death.

The Panic Virus by Seth Mnookin is currently available on paperback and Kindle wherever books are sold. For further reading on how to deal with the complexities of the anti-vaccine movement aftermath, we suggest the recent book On Immunity: An Inoculation by Northwestern University lecturer Eula Bliss.

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development. Follow us on Twitter and Facebook. Subscribe to our podcast on SoundCloud or iTunes.

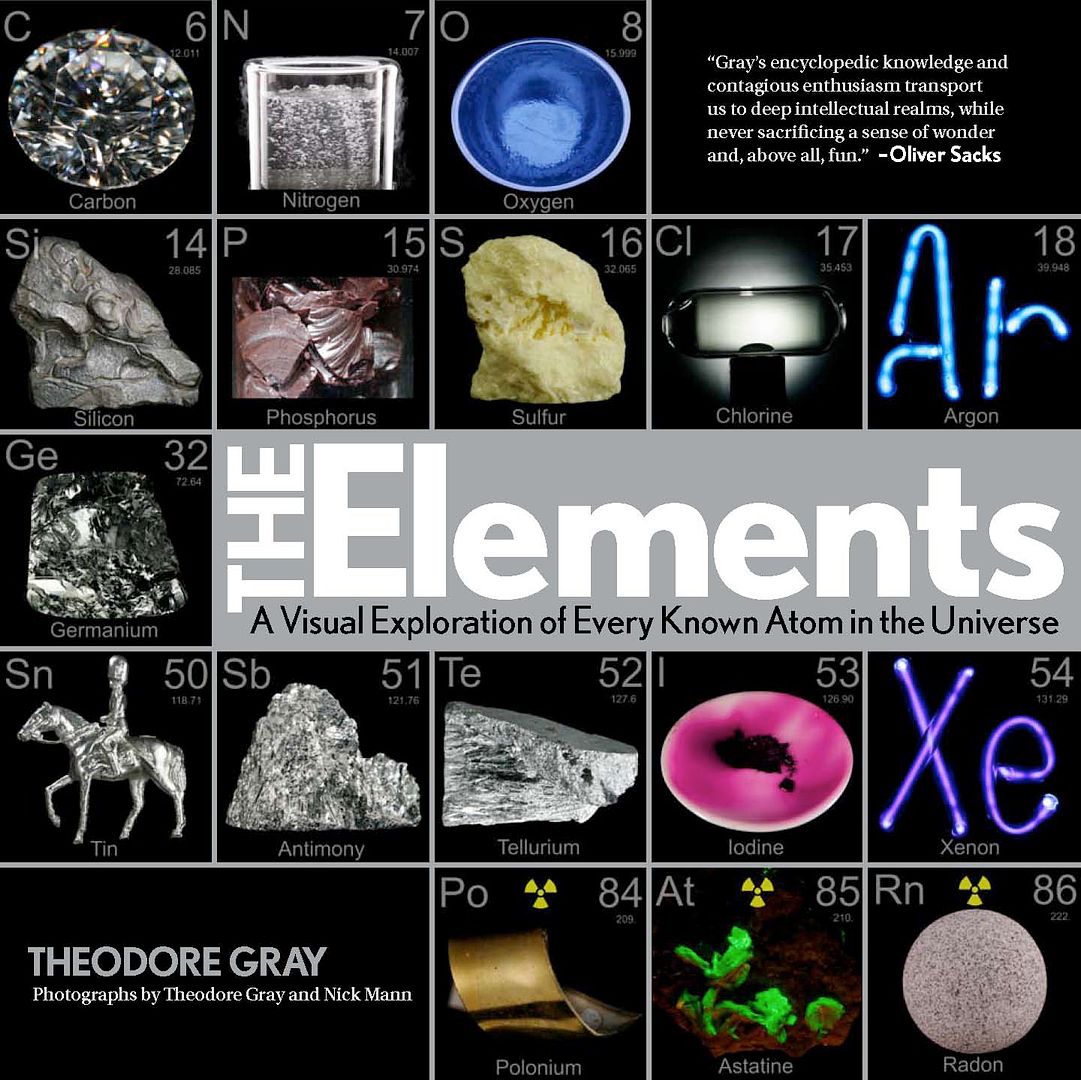

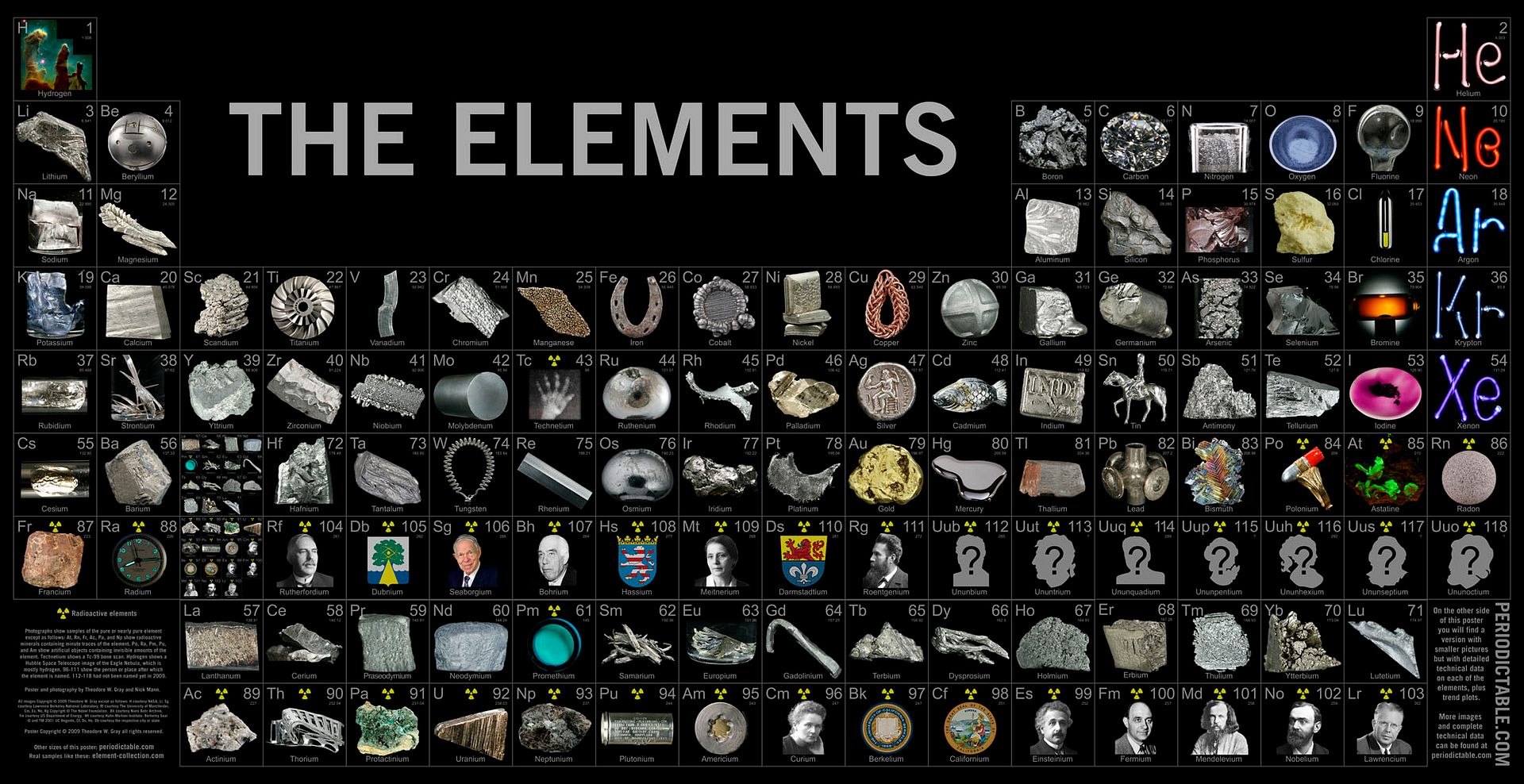

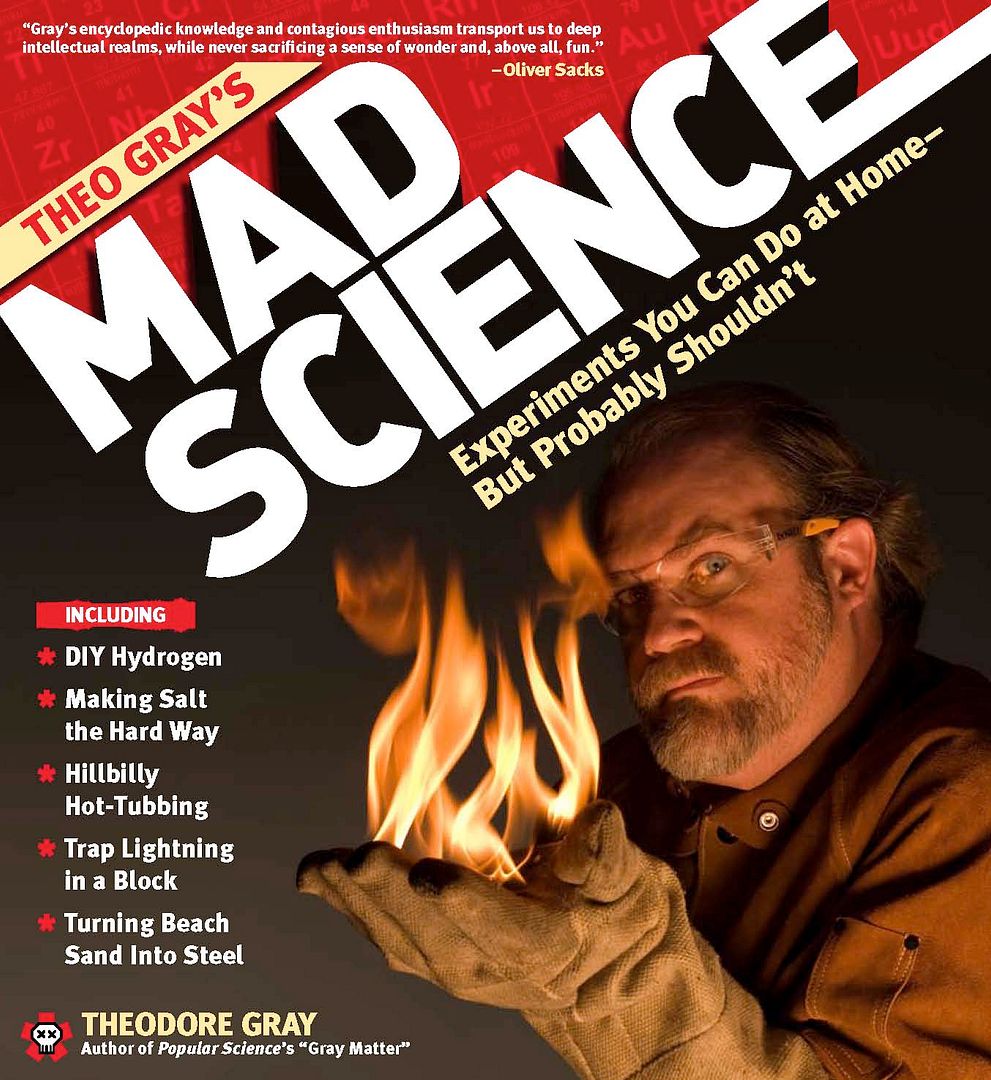

He is one of the most popular and explosive (sometimes literally!) science columnists of our day. Since 2005, he has written the Popular Science blog Gray Matter. He has been willing to try virtually any chemistry experiment known to man, all in the interest of proving a theory and educating (and entertaining) a fortunate lay audience. He has created the most widely acclaimed periodic table ever, which has been replicated into posters, an actual table, playing cards, and now, a gorgeous full-color hardcover book. Who is this mad scientist I am referring to? Why, Theodore Gray, of course! For Day 3 of Science Week, ScriptPhD.com is thrilled to review his new book The Elements, an equal parts homage to chemistry and photography. Editor Jovana Grbić sat down with Theo in a candid, in-depth interview about his books, his favorite elements, and the responsibility science writers have to informing the public. More more content, please click “continue reading.”

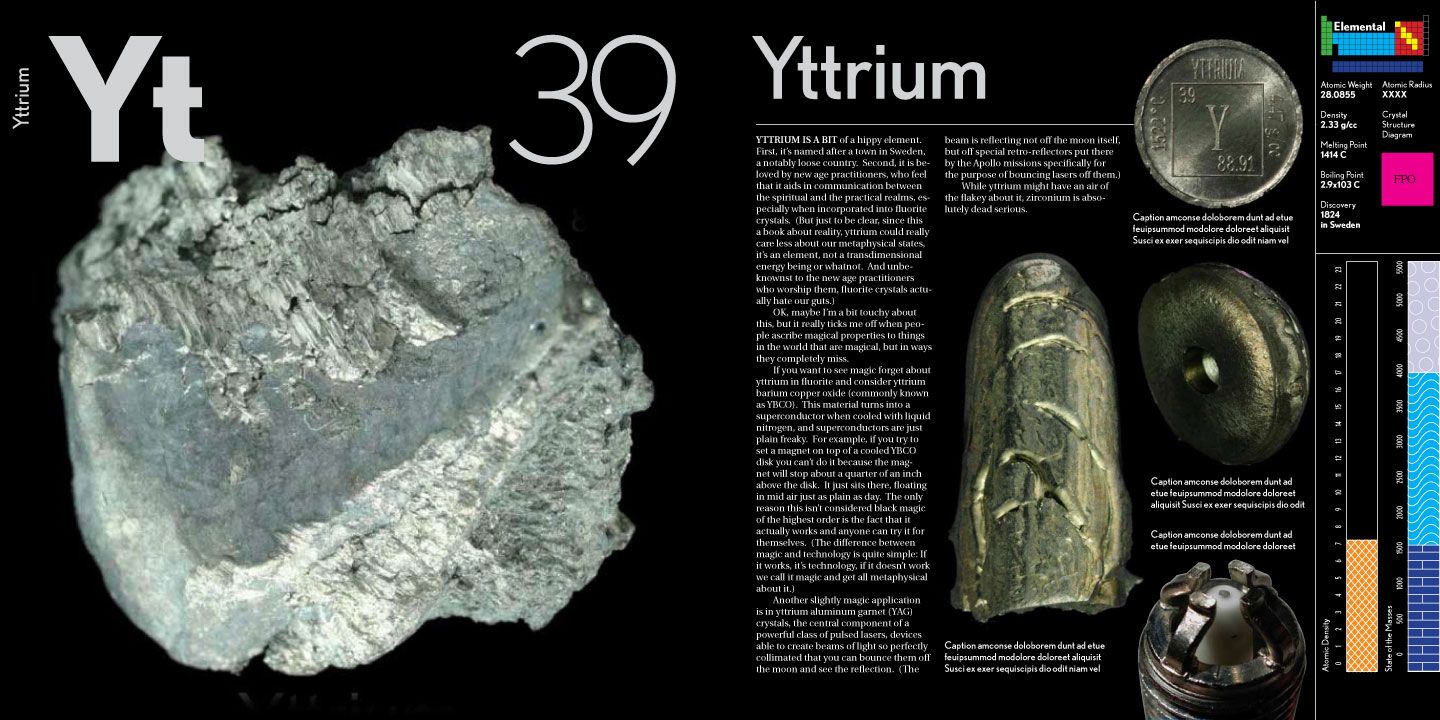

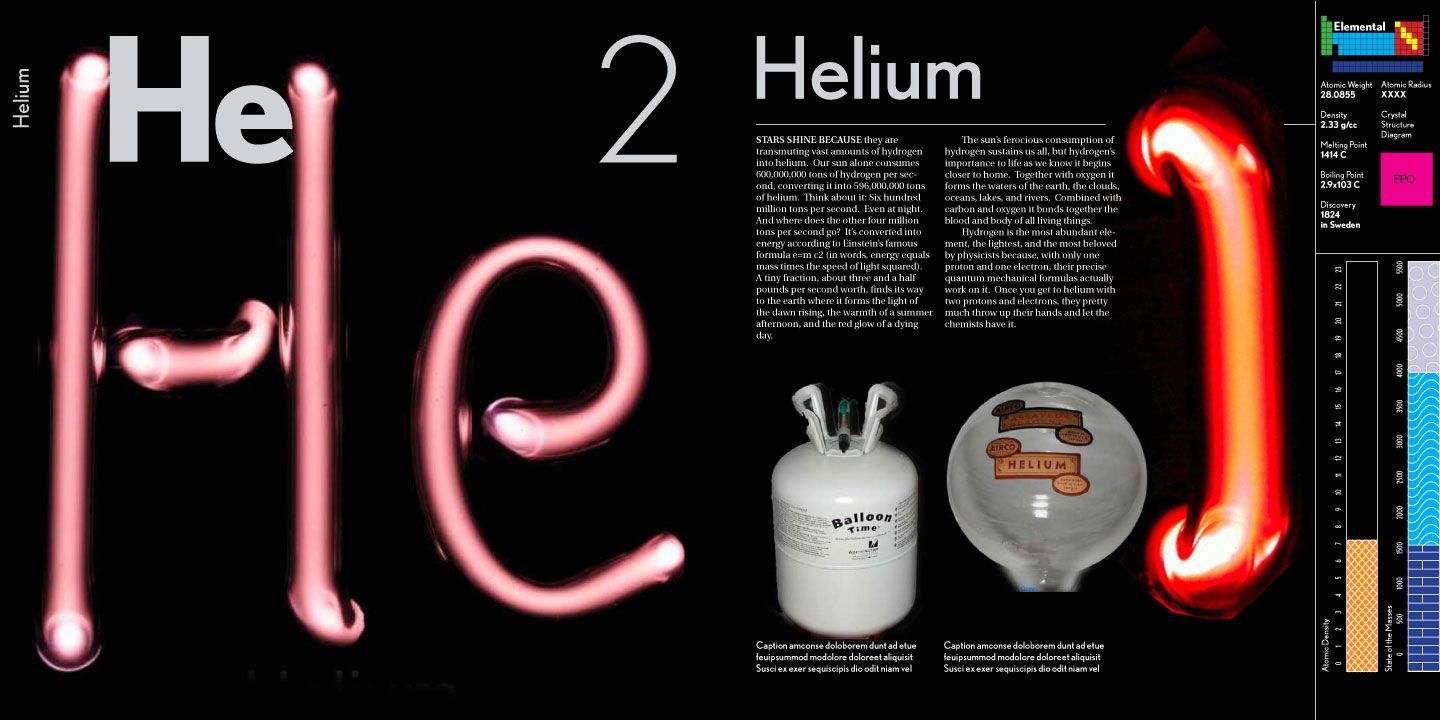

It is a staple of every high school and college science class. Its familiar shape has stayed largely the same since 1869, when Siberian chemistry professor Dmitry Ivanovich Mendeleev first grouped chemicals together according to similar properties. It is indispensable to scientists of all disciplines, and has even inspired our very own ScriptPhD.com logo! It is, of course, the periodic table of the elements. There is an immense challenge in taking such a well-known, immutable scientific entity and making people see it in a way it has never been seen before. And to do so using photography and creative writing? To the moon, Alice! Yet in Theo Gray’s gorgeous new book The Elements, this is precisely what occurs—a rebirth for ruthenium, rhodium, radium, rubidium… and the rest. Each page (as seen below) is elegantly laid out with gallery quality photography, sometimes of compounds, minerals and applications that would surprise you, and fascinating stories that turn each element into its own unique chapter in the hallowed Bible of chemical history.

Chemistry is the central science. But as you get to know the periodic table better while reading The Elements, it quickly becomes apparent that chemistry is also a science with much character. It is smelly, as is the case with sulfur. It’s sometimes a mouthful, as in the longest element name, praseodymium. It helps us control mood swings, as is the case with lithium. It helps us when we’ve overdone it at the weekend barbeque, as is the case with bismuth subsalicylate. Perhaps you know it better as Pepto-Bismol. Chemistry helps doctors and scientists to save lives. A radioactive isotope of technetium is naturally bone-seeking, and helps radiologists diagnose everything from compound fractures to cancer. Should you ever need to get an MRI, chances are you’ll have to consume a contrast dye composed of the element gadolinium. Sometimes, a fickle element both saves and takes lives. Chlorine, for example, has saved hundreds of millions of lives as an antiseptic and disinfectant in small quantities, yet is poisonous in large quantities. Likewise, selenium is an essential nutrient, but toxic in large doses. Gray also pays tribute to a sullied, marginalized element that has gotten a bad rap over the years: zirconium. If you’re considering proposing to that special someone, zirconium, like the overpriced aged carbon of which it is a replica, is near the top of the hardness scale and equally as beautiful for a fraction of the cost! On an unrelated note, thallium is one of the most effective poisons on the periodic table, owing to common symptoms that few doctors can pinpoint. For utter destruction on a wanton scale, however, one need look no further than uranium:

What is most unique and attractive about The Elements is the lengths to which it goes to envelop artists and creatives in the world of science, many of whom would be surprised how much of their craft they owe to chemistry. Iconic photographers like Ansel Adams would be nothing without magnesium, which has been widely used in camera flashes to provide light. For you font and graphic design nerds out there, one thing the typeface documentary Helvetica omitted is the magic that lies in the combination of antimony, lead and tin—it expands when solidified from a molten state. Voila! 650 years (and counting) of movable typeface. Film buffs who have enjoyed movies like Avatar (and the upcoming Hubble 3D) on IMAX would be interested to know that IMAX projectors use 15 kW short-arc Xenon projector lamps. Jimmy Hendrix, Stevie Ray Vaughan, Eric Clapton, ZZ Top, BB King, and countless other guitar legends would be silenced were it not for the obscure element samarium, which in combination with cobalt is used as a magnet for electric guitar pickups. And for all of you DJs and musical purists who agree with The ScriptPhD that no musical sound is sweeter and sharper than that of a vinyl record, did you know that phonograph needle tips are made of osmium?

Interview With Theo Gray

ScriptPhD.com Editor Jovana Grbic was fortunate to chat with Theo Gray recently, and was eager to get his perspective on the making of The Elements and Mad Science books, and some more meaty science policy issues as well.

ScriptPhD.com: Tell me a bit about the idea to put together The Elements.

Theo Gray: The book goes back quite a ways. I started collecting elements, really by accident, in 2002. We needed a table for the common area of the office I was moving into, and I didn’t want some kind of an ugly thing that you could get from an office supply catalog, so I had tables on my mind. Then, I was reading Uncle Tungsten by Oliver Sachs, and he describes a periodic table that he used to visit at the science museum. I took that literally, and thought the table literally looked like a table, and that seemed like the coolest thing—someone should make a periodic table [with slots for the elements], and at that point no one ever had! Because of the way the table was designed, it was easy to make little compartments underneath each element where you could put a sample of the element. This was right around when eBay was exploding, and it turned out you could get a great many elements there. It kind of happened by accident. One table led to another, and pretty soon, I had thousands of element [samples], pure and industrial compounds. Then I started photographing them to remember what they are. I put the cataloged list and accompanying photographs on the web, and people liked it, and the Ig Nobel Award I got in 2002 made me think that this is something other people might be interested in, too.

One thing led to another, and the cameras started getting fancier, and the photography started getting better, and pretty soon I thought I could make a poster [of the elements]. This poster is now seem on TV shows from MythBusters to Hannah Montana, which eventually led to The Elements.

SPhD: One of the things I really loved about The Elements was the humor interspersed throughout the copy. You manage to really make it fun, lively and at times hilarious. Was this writing style meant to parallel how you view science, and chemistry in particular?

TG: The other thing that I’d been doing [while compiling the book] every month, was writing a column for Popular Science Magazine, Gray matter. And it’s popular, it’s a popular magazine, as the name implies, written very much for a lay audience. So I did that every month, writing 350-450 words about a certain topic of science and working with excellent editors there to refine the language to compete with other popular publications—immediately engaging, and with some fun in it. I think it’s fair to say that over the course of the five years that I’ve been writing the column, I’d refined my ability to write consicely about a focused topic. And that’s what The Elements book is, a hundred Popular Science columns all wrapped up. In some cases, the story behind an element was so much more interesting than any practical uses we could highlight. [Editor’s note: radium is a particularly good example of this!]

SPhD: What were the biggest challenges during the making of the book and photography of the elements?

TG: In terms of the writing of the book, the rare earths, or Lanthanide series, was the toughest by far, because all of the Lanthanides are very similar [in chemical property]. In many cases, for commercial applications, they’re essentially interchangeable. If you’re making lighter flicks, it really doesn’t matter what rare earth you’re using—and they don’t even purify them, they just take them out of the ground. And many of them don’t really have any interesting applications. Although, it was interesting to discover Thulium (Tm 69), for example, which I’d gone for years thinking that no one actually cared about. But it turns out in the lighting industry they care passionately about thulium, and they couldn’t live without it [for metal halide lamps].

The challenge with the photography is that these are all essentially lumps of gray metal. 90%+ of all the elements are gray metals and shapeless. One of the few other photo periodic tables out there was published in the 1960s by Time-LIFE, and they all look the same—not very interesting! Our job was exactly like the job of a commercial photographer, an advertising photographer. They’re given a product that might be the most boring thing you ever saw, and they have to bring out its inner beauty by way of lighting and arrangement. We tried to think of the most exciting examples of each metal. We also did cheat a bit, with some of the beautiful, colorful crystals, which are not pure elements but rather compounds. But it is an excuse to put a splash of color on every page!

SPhD: You know I’m going to ask… you’re the Element King… What’s your favorite element and why?

TG: Ahh, the favorite element question! My first answer is that I don’t have a favorite child, either. But there’s different elements that I like for different reasons. Sodium, for example, if you have a lake near-by, is the element you want to have. [Editor’s note: BE CAREFUL! HIGHLY EXPLOSIVE!] On the other hand, something like titanium is a wonderful metal in every way—it doesn’t rust, it’s malleable, highly useful, strong, and many of its applications are interesting and exotic. Copper is so great as well, because it’s the only colored metal that is reasonably priced and not explosive. Cesium explodes, and gold is very expensive. That leaves copper, but people don’t tend to make sophisticated shapes out of it other than jewelry. But if I had to name two, it would be sodium and titanium.

SPhD: Let’s talk about your other book for a moment, Mad Science. Some of my favorite experiments that I want to replicate are the lightbulb, homemade pencils, 1-volt liquid battery (which I’ll use to charge up my iPod), plating the iPod, and my personal favorite, preserving a snowflake. Was there an experiment in this book that made it in or didn’t where you either felt like your life was in danger or you were like, “OK, change of plans, we’re not doing this.”?

TG: I have a policy of not doing anything dangerous. These experiments [from the book] are only dangerous if you don’t do them right, which I explain fairly well in the safety section. Because basically, I’m a complete ninny. I’m terrified of that stuff, which is the way that you ought to be. There is a good bit of thought that went into the worst case scenario, and if there was a shred of doubt, we rethought the experiment—smaller scale, or do it differently. One of the advantages of doing it for photography as opposed to in person is that we were able to get away with extremely small quantities. We also hired specialists where applicable, such as an electrical engineer for shrinking coin trick, or an industrial chemist for the chlorine experiment.

The one experiment that I suggest your readers do is the snowflake one, which is just so nice, and only took me three or four tries. The key is to keep your slide really cold and pre-cooled, and to handle them with your hands the least amount possible.

SPhD: You are, of course, most well known for your Popular Science column Gray Matter. How has writing Gray Matter, particularly focused for a lay audience, changed your role in science?

TG: It’s interesting to be faced with the challenge of trying to explain something that is actually quite complicated and deep in a format where you only have a few hundred words and you can’t assume that your audience has four semesters of college chemistry. If I were writing for Scientific American, it would be quite different and you could use a certain shorthand quite freely. Here, I have not not only explain everything, but also make it fun and entertaining. The most important thing is that I have an opportunity to speak to people, particularly young people, who probably aren’t getting any actual science anywhere else. Rather than preaching to the choir about the value and interestingness of science, I can reach out to a new audience. Often in lay magazines, it’s frustrating to read so much pseudo-science because the people doing it don’t actually know what they’re talking about. The other thing I like to do is scatter some breadcrumbs throughout my writing to leave hints or terms that can’t really be explained to encourage people to look things up on their own.

SPhD: So much of our modern culture is influenced by the growth of technology and science, which play a huge role in our lives and economy than ever before. And yet, as a whole, mainstream public knowledge of basic science can be shockingly absent or misinformed. What is the single most important thing people like you, myself and others in the science community can do to mitigate this?

TG: There’s a couple of things. One is, and I’ve written a couple of blog posts about this for Powell’s Books, that you need to be relatively fearless in getting out there and telling the truth without worrying about repercussions or consequences. I’m talking about things like creationism or homeopathy, which are two basically stupid ideas which are very widely believed. People like me have a responsibility not to beat around the bush [as to their accuracy or lack thereof]. One needs to have strong attitudes because that’s what gets people riled up. At the same time, one needs to communicate that science is something that is worth putting effort into and learning about, because it’s very powerful. If you understand it, and your competitor doesn’t, you win, in many, many situations. We see this both in technology and at the societal level, one that we’re frankly losing to China. While we’re arguing about evolution and homeopathy, they’re gathering all the natural resources they can to become the dominant global economy next Century.

SPhD: You are one of the few scientists that have crossed the barrier to entertainment and wider popular appeal. Why do you think more academics have not? Is it a problem of the public welcoming these figures, hesitation in the academic community of going mainstream, or something in the middle?

TG: It depends. There’s different motivations. I, for example, grew up in an entirely academic household; both of my parents were math professors. I completely understand that world and that mindset. The kind of articles that I write for Popular Science would be considered more than a little bit embarrassing if I were an academic and had to worry about tenure committees and citations of academic papers. It’s not a very respectable profession, from an academic point of view, and I think that keeps a lot of people out who could write for a broader popular audience. It’s also a quite different skill, one that’s taken me decades, to develop the writing style that works for a lay audience—and it’s not easy to do.

And then on the other side, there’s a resistance among the publishers and media types to take science seriously because they assume it’s going to be boring. It irritates me greatly when TV shows about science end up being frantically edited, with lots of flashy graphics going up. And you can just tell that what happened was that none of the people involved knew anything about science (or possibly cared). But if you look at a show like MythBusters, for example, it’s a fantastic science show.

SPhD: Yes! We love MythBusters!

TG: They are one of the most successful of all cable shows, and they are 95% a science show wrapped up around the theme of a “myth” that they have to “bust.” Fundamentally, what they do is pose a question and then hypothesize and answer it using the scientific method. I don’t know if people appreciate how revolutionary it is for them to do that consistently.

SPhD: This is why ScriptPhD.com loves The Discovery Channel and MythBusters so much. We are in contact with them, we’re big supporters, and we wish them, and you, a lot of luck with shepherding the next generation of curious young scientists!

TG: Delightful to talk to you as well. Thanks!

~*ScriptPhD*~

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development.

Follow us on Twitter and our Facebook fan page. Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

]]>