In 2011, a cognitive supercomputing system developed at IBM named “Watson” was pitted against, and subsequently defeated, two of the most successful Jeopardy! game-show contestants of all time. A project five years in the making, Watson was initially developed as a “Grand Challenge” successor to Deep Blue, the machine that beat Gary Kasparov at chess, and was a prototype for DeepQA, a question/answer natural language analysis architecture. Since his Jeopardy! triumph, however, Watson has been successfully applied towards improving health care, oncology, business applications and soon enough… even education. At the same time that IBM has been expanding Watson’s cognitive computing abilities, they’ve also been brilliantly marketing him to the general public through a series of traditional and interactive ads.

As part of our ongoing “Selling Science Smartly” series, we analyze the Watson campaign in more depth and feature an exclusive and insightful podcast conversation with the IBM marketing team behind it.

Campaign: Watson

Agency: IBM/Ogilvy&Mather

Industry: Cognitive computing/information technology

Quick thought experiment. Name at least a couple of technology advertising campaigns (not including Apple) that have been so memorable and clever, they either compelled you to buy a product or piqued your curiosity to learn more about it. Chances are, you can’t. For one thing, outside of computers and gadgets, “big picture” technologies like cloud computing, artificial intelligence and artificial neural networks have still not become fully mainstream. For another, like many high-end sophisticated science applications, it is difficult to communicate such abstract applications in bite-size pieces. IBM’s recent Watson campaign, centered around its powerful cognitive question/answer (QA) computing device, defies conventional tech branding. It’s instantaneously attention-getting. It features Watson’s attributes by incorporating one of the hallmark rules of film-making/screenwriting: show, don’t tell. Most importantly, humans are the centerpiece of each commercial/spot, which is an important antidote to Hollywood-induced fears of robotic takeover and a more realistic depiction of how we will really subsume AI into our existence through small steps.

Here is Watson summarizing his seemingly endless array of capabilities for integration of deep learning:

Here is Watson explaining his capacity for improving digital health and diagnostics in medicine to an adorable young patient:

Recently, Watson displayed his technological versatility in an interactive campaign where he helped design a supermodel’s “Cognitive Dress.” The dress was equipped with lighting to monitor real-time social media reactions and represents an example of augmenting the creative process with technology in the future.

Why It’s Good Science Advertising

Whether he’s enjoying a one-on-one conversation with virtually any human, designing dresses or helping people cook gourmet meals, Watson comes across as versatile, approachable and interactive. Soon, Watson will even produce meta-advertising, in the form of cognitive marketing — enabling consumers to have remote brand-related conversations with Watson Ads suited to their individual needs and questions about a particular product. As illustrated in the video below, the Watson campaign, like the technology itself, represents a total commitment to brand awareness, IBM’s core mission and the eventual potential of the cognitive technology device. And, it’s memorable!

Why It Works

With a cognitive machine as powerful and versatile as Watson, brand messaging presents two major challenges: succinctly communicating the complex framework of solutions for consumers, businesses and institutions, and doing so in an emotionally engaging manner. Watson succeeds on both accounts. He describes his capabilities from a first-person perspective, not through omniscient narration. He functions through interlocution, which lends an intimacy to the commercials — any one of us might find ourselves interacting with Watson and requesting his help. He is fun and funny; brilliant yet adorably inept in human slang; cheeky yet serious; always helpful, curious and collaborative. In essence, Watson has been branded as an anthropomorphic companion instead of a sterile robot. 21st Century technology will inevitably be personal, inclusive and integrated into our lives. The Watson campaign feels like the realistic unveiling of the cognitive computing era. Take a look at Watson’s conversation with Ridley Scott about artificial intelligence, as portrayed in Hollywood (referenced in our podcast below):

What Other Science Campaigns Can Learn From This One

Creative risk-taking is essential for successfully marketing sophisticated technology, not just in the content itself, but in how it is crafted. In the immediate predecessor to the Watson campaign, a series of spots entitled “Made With IBM” traveled across three continents to share short, documentary-like stories about cross-applications of a panoply of IBM technology and its relevance in today’s connected world. Accordingly, the aggregate Watson ads and interactive spots present an engaged, personalized look at how cognitive computing will facilitate faster, more improved and easier tasks in all areas of human life in the future while making an immediate impact in several industries right now. Indeed, IBM’s commitment to incorporating storytelling across all of its content extends to the unusual move of hiring screenwriters to join its marketing team. IBM also partnered with the TED Institute for multi-year thought leadership symposium where critical ideas related to technology and data-driven computing, along with the ways they could change the world, were shared by leading experts. In the process, this multi-platform approach not only taps into the next generation of consumers, but slowly assuages understandable reservations about artificial intelligence.

To help gain insight into the creative development and thought process behind the Watson campaign, as well as the greater context of using didactic advertising and thought leadership to inform about complex technology, ScriptPhD.com was joined for a conversation with IBM’s Vice President of Branded Content and Global Creative Ann Rubin and Watson Chief Marketing Officer Stephen Gold. Listen to our podcast below:

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development. Follow us on Twitter and Facebook. Subscribe to our podcast on SoundCloud or iTunes.

From its earliest inceptions, science fiction has blurred the line between reality and technological fantasy in a remarkably prescient manner. Many of the discoveries and gadgets that have integrated seamlessly into modern life were first preconceived theoretically. More recently, the technologies behind ultra-realistic visual and motion capture effects are simultaneously helping scientists as research tools on a granular level in real time. The dazzling visual effects within the time-jumping space film Interstellar included creating original code for a physics-based ultra-realistic depiction of what it would be like to orbit around and through a black hole. Astrophysics researchers soon utilized the film’s code to visualize black hole surfaces and their effects on nearby objects. Virtual reality, whose initial development was largely rooted in imbuing realism into the gaming and video industries, has advanced towards multi-purpose applications in film, technology and science. The Science Channel is augmenting traditional programming with a ‘virtual experience’ to simulate the challenges and scenarios of an astronaut’s journey into space; VR-equipped GoPro cameras are documenting remote research environments to foster scientific collaboration and share knowledge; it’s even being implemented in health care for improving training, diagnosis and treatment concepts. The ability to record high-definition film of landscapes and isolated areas with drones, which will have an enormous impact on cinematography, carries with it the simultaneous capacity to aid scientists and health workers with disaster relief, wildlife conservation and remote geomapping.

The evolution of entertainment industry technology is sophisticated, computationally powerful and increasingly cross-functional. A cohort of interdisciplinary researchers at Northwestern University is adapting computing and screen resolution developed at DreamWorks Animation Studios as a vehicle for data visualization, innovation and producing more rapid and efficient results. Their efforts, detailed below, and a collective trend towards integration of visual design in interpreting complex research, portends a collaborative future between science and entertainment.

Not long into his tenure as the lead visualization engineer at Northwestern University’s Center For Advanced Molecular Imaging (CAMI), Matt McCrory noticed a striking contrast between the quality of the aesthetic and computational toolkits used in scientific research versus the entertainment industry. “When you spend enough time in the research community, with people who are doing the research and the visualization of their own data, you start to see what an immense gap there is between what Hollywood produces (in terms of visualization) and what research produces.” McCrory, a former lighting technical director at DreamWorks Animation, where he developed technical tools for the visual effects in Shark Tale, Flushed Away and Kung Fu Panda, believes that combining expertise in cutting-edge visual design with emerging tools of molecular medicine, biochemistry and pharmacology can greatly speed up the process of discovery. Initially, it was science that offered the TV and film world the rudimentary seeds of technology that would fuel creative output. But the TV and film world ran with it — so much so, that the line between science and art is less distinguishable than in any other industry. “We’re getting to a point [on the screen] where we can’t discern anymore what’s real and what’s not,” McCrory notes. “That’s how good Hollywood [technology] is getting. At the same time, you see very little progress being made in scientific visualization.”

What is most perplexing about the stagnant computing power and visualization in science is that modern research across almost all fields is driven by extremely large, high-resolution data sets. A handful of select MRI imaging scanners are now equipped with magnets ranging from 9.4 to 11.75 Teslas, capable of providing cellular resolution on the micron scale (0.1 to 0.2 millimeters versus 1.5 Tesla hospital scanners, at 1 millimeter resolution) and cellular changes on the microsecond scale. The ultra high-resolution imaging provides researchers with insight into everything from cancer to neurodegenerative diseases. While most biomedical drug discovery today is engineered by robotics equipment, which screens enormous libraries of chemical compounds for activity potential around the clock in a “high-throughput” fashion — from thousands to hundreds of thousands of samples — data must still be analyzed, optimized and implemented by researchers. Astronomical observations (from black holes to galaxies colliding to detailed high-power telescope observations in the billions of pixels) produce some of the largest data sets in all of science. Molecular biology and genetics, which in the genomics era has unveiled great potential for DNA-based sub-cellular therapeutics, has also produced petrabytes of data sets that are a quandary for most researchers to store, let alone visualize.

Unfortunately, most scientists can’t allocate dual resources to both advancing their own research and finding the best technology with which to optimize it. As McCrory points out: “In a field like chemistry or biology, you don’t have people who are working day and night with the next greatest way of rendering photo-realistic images. They’re focused on something related to protein structures or whatever their research is.”

The entertainment industry, on the other hand, has a singular focus on developing and continuously perfecting these tools, as necessitated by proliferation of divergent content sources, screen resolution and powerful capture devices. As an industry insider, McCrory appreciates the competitive evolution, driven by an urgency that science doesn’t often have to grapple with. “They’ve had to solve some serious problems out there and they also have to deal with issues involving timelines, since it’s a profit-driven industry,” he notes. “So they have to come up with [computing] solutions that are purely about efficiency.” Disney’s 2014 animated science film Big Hero 6 was rendered with cutting-edge visualization tools, including a 55,000-core computer and custom proprietary lighting software called Hyperion. Indeed, render farms at LucasFilm and Pixar consist of core data centers and state-of-the-art supercomputing resources that could be independent enterprise server banks.

At Northwestern’s CAMI, this aggregate toolkit is leveraged by scientists and visual engineers as an integrated collaborative research asset. In conjunction with a senior animation specialist and long-time video game developer, McCrory helped to construct an interactive 3D visualization wall consisting of 25 high-resolution screens that comprise 52 million total pixels. Compared to a standard computer (at 1-2 million pixels), the wall allows researchers to visualize and manage entire data sets acquired with higher-quality instruments. Researchers can gain different perspectives on their data in native resolution, often standing in front of it in large groups, and analyze complex structures (such as proteins and DNA) in 3D. The interface facilitates real-time innovation and stunning clarity for complex multi-disciplinary experiments. Biochemists, for example, can partner with neuroscientists to visualize brain activity in a mouse as they perfect drug design for an Alzheimer’s enzyme inhibitor. Additionally, 7 thousand in-house high performing core servers (comparable to most studios) provide undisrupted big data acquisition, storage and mining.

Could there be a day where partnerships between science and entertainment are commonplace? Virtual reality studios such as Wevr, producing cutting-edge content and wearable technology, could become a go-to virtual modeling destination for physicists and structural chemists. Programs like RenderMan, a photo-realistic 3D software developed by Pixar Animation Studios for image synthesis, could enable greater clarity on biological processes and therapeutics targets. Leading global animation studios could be a source of both render farm technology and talent for science centers to increase proficiency in data analysis. One day, as its own visualization capacity grows, McCrory, now pushing pixels at animation studio Rainmaker Entertainment, posits that NUViz/CAMI could even be a mini-studio within Chicago for aspiring filmmakers.

The entertainment industry has always been at the forefront of inspiring us to “dream big” about what is scientifically possible. But now, it can play an active role in making these possibilities a reality.

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development. Follow us on Twitter and Facebook. Subscribe to our podcast on SoundCloud or iTunes.

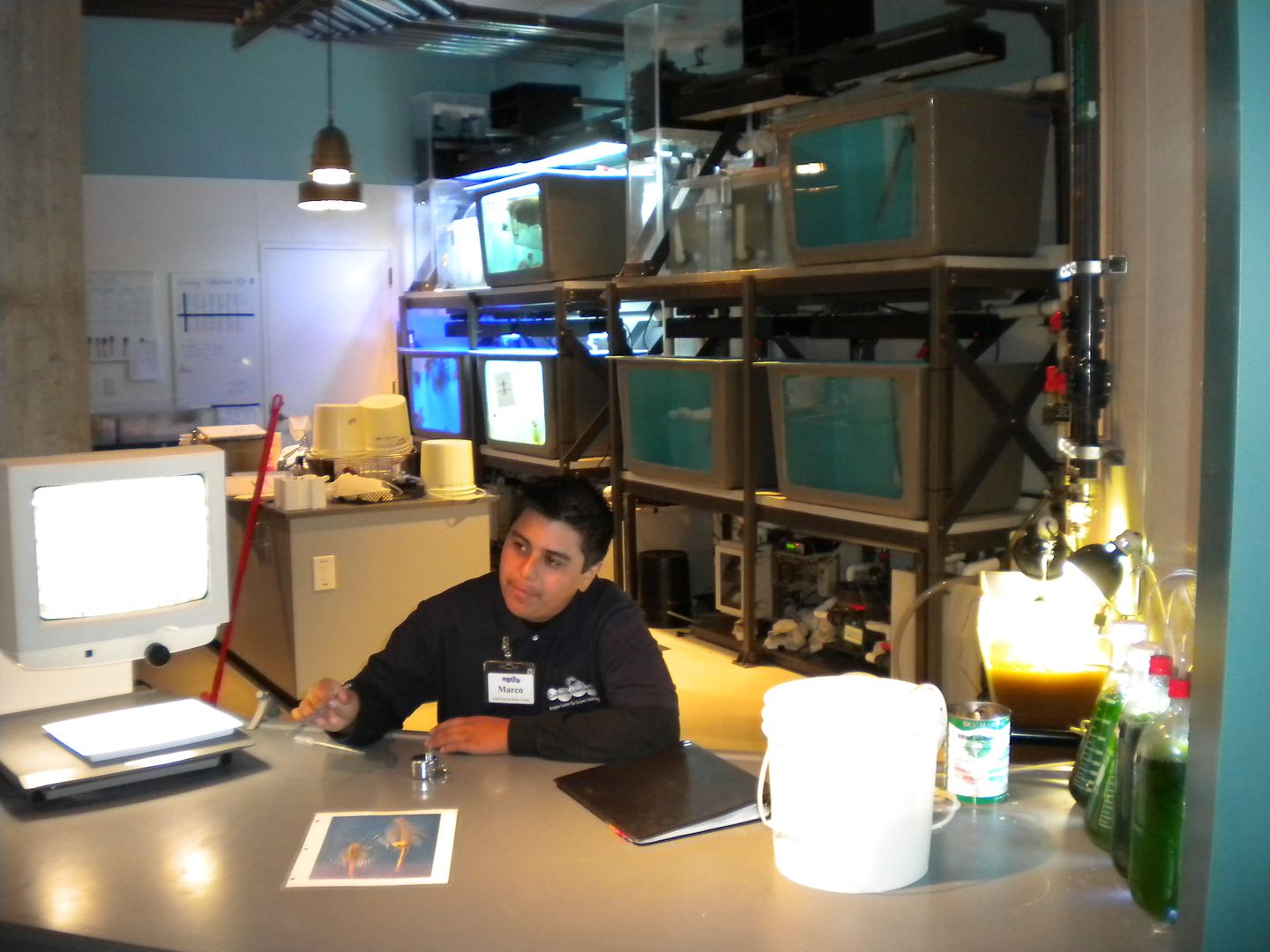

The current scientific landscape can best be thought of as a transitional one. With the proliferation of scientific innovation and the role that technology plays in our lives, along with the demand for more of these breakthroughs, comes the simultaneous challenge of balancing affordable lab space, funding and opportunity for young investigators and inventors to shape their companies and test novel projects. Los Angeles science incubator Lab Launch is trying to simplify the process through a revolutionary, not-for-profit approach that serves as a proof of concept for an eventual interconnected network of “discovery hubs”. Founder Llewelyn Cox sits down with ScriptPhD for an insightful podcast that assesses the current scientific climate, the backdrop that catalyzed Lab Launch, and why alternatives to traditional avenues of research are critical for fueling the 21st Century economy.

As science and biotechnology innovation go, we are, to put it in Dickensian terms, in the best of times and the worst of times.

On the one hand, we are in the midst of a pioneering golden age of discovery, biomedical cures and technological evolution. It seems that every day brings limitless possibility and unbridled imagination. Recent development of CRISPR gene-editing machinery will facilitate specific genome splicing and wholescale epigenetic insight into disease and function. Immunotherapy, programming the body’s innate immune system and utilizing it to eradicate targeted tumors, represents the biggest progress in cancer research in decades. For the first time ever, physicists have detected and quantified gravitational waves, underscoring Einsteins theory of gravity, relativity and how the space continuum expands and contracts. The private company SpaceX landed a rocket on a drone ship for the first time, enabling faster, cheaper launches and reusable rockets.

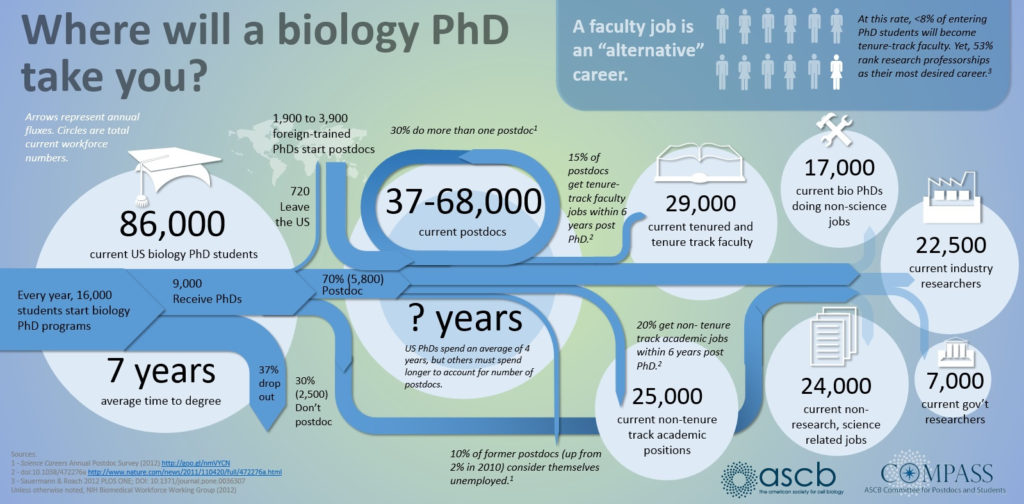

Despite these exciting and hopeful advancements, many of which have the potential to greatly benefit society and quality of life, there remain tangible challenges to fostering and preserving innovation. Academic science produces too many PhDs, which saturates the job market, stifles viable prospects for the most talented scientists and even hurts science in the long run. Exacerbating this problem is a shortage of basic research funding in the United States that represents the worst crisis in 50 years. And while European countries experience a similar pullback in grant availability, developing countries are investing in research as an avenue of future economic growth. High-risk, high-reward research, particularly from young investigators, is suppressed at the expense of “safe research” and already-wealthy, established labs. Conduits towards entrepreneurship are possible, many through commercializing academic findings, but few come without strings attached, start-up companies are in a 48% decline since the 1970s. With research and development stagnating at most big pharmaceutical companies and current biomedical research growth unsustainable, there is an unprecedented opportunity to disrupt the innovation pipeline and create a more robust economy.

In an effort to boost discovery and development, there has been a permeation of venture capital accelerators and think-tank style early stage incubators from the technology sector into basic science; indeed it’s experiencing a proliferating boom. Affordable space, world-class facilities, access to startup capital and a opportunity to explore high-risk ideas — all are attractive to young academics and scientific entrepreneurs. Even pharmaceutical giants are spawning innovation arms as potential sources of future ideas. Large cities like New York are even using incubator space as a catalyst for growing a localized biotechnology-fueled economy. Such opportunities, however, don’t come without risk and collateral to innovators. As Mike Jones of science, inc. warns, the single biggest question that innovators must asses is: “Is the value I am getting equal to the risk I am saving, through equity?” Many incubators and accelerators act as direct conduits to academia and industry, both for talent recruitment and retention of intellectual material. In fact, the business model governing incubator space and asset allocation can often be nebulous, and sometimes further complicated by mandatory “collaborative” sharing not just of materials and space, but data and intellectual property. Even wealthy investors, who are now underwriting academic and private sector research, want a voice in the type of research and how it is conducted.

Amidst this idea-driven revolution was borne the concept of Lab Launch, a transformative permutation of incubator space for fostering pharmaceutical and biotechnology innovation. The fundamental principle behind Los Angeles-based Lab Launch is deceptively simple. As a not-for-profit endeavor, it provides simple, sleek and high-level equipment and space for life science and biotechnology experimentation. Because all shared equipment is donated as overflow from companies and laboratories that no longer need it, costs are minimized towards laboratory management fees and rental of facilities. As a stripped-down discovery engine model, this allows Lab Launch scientists to keep 100% of their intellectual property and equity, something that is virtually unheralded for young innovators at early-development stages. On a more complex level, the potential wide-scale benefits of Lab Launch (and future copycat spawns) are profound and resonant. In an industry where the Boston-San Francisco-San Diego triumvirate presents a near-hegemony for biotechnology funding, development and intellectual assets, the growth of simple, inexpensive science incubators in large cities carries tremendous economic upside. Critics might point out the lack of substantive guidance and elite think tank access of such a platform, yet 90% of all incubators and accelerators still fail, regardless. Moreover, selection criteria are often biased towards specific business interests or research aims that buoy academia and venture capital profiteers, which weed out the most high-risk ideas and participants. How, for example, would a scientist without a PhD or prestigious pedigree get access to a mainstream incubator lab space? How would a radically non-traditional idea or approach merit mainstream support or funding? A recent Harvard Business Review article suggests that lean start-ups with the most efficient, bare-bones development models, have far higher success rates and should be the template for driving an innovation-based economy. As elucidated in the podcast below, opening doors to facilitate proof-of-concept innovation and linking a virtual network of lab spaces will give rise to not just the next Silicon Valley, but the great scientific breakthroughs of tomorrow.

Lab Launch founder Dr. Llewellyn Cox sat down with ScriptPhD for a podcast interview to talk about his revolutionary not-for-profit startup incubator and the challenging scientific environment that inspired the idea. Among our topics of discussion:

•How lack of funding and overflow of PhDs in the current scientific climate stifles creativity and innovation

•Why biotechnology will cultivate exciting new industries in the 21st Century

•How no strings attached incubators like Lab Launch help give rise to Silicon Valleys of the future

•Why we should in fact be hopeful about how scientific progress is advancing

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development. Follow us on Twitter and Facebook. Subscribe to our podcast on SoundCloud or iTunes.

It has become compulsory for modern medical (or scientifically-relevant) shows to rely on a team of advisors and experts for maximal technical accuracy and verisimilitude on screen. Many of these shows have become so culturally embedded that they’ve changed people’s perceptions and influenced policy. Even the Gates Foundation has partnered with popular television shows to embed important storyline messages pertinent to public health, HIV prevention and infectious diseases. But this was not always the case. When Neal Baer joined ER as a young writer and simultaneous medical student, he became the first technical expert to be subsumed as an official part of a production team. His subsequent canon of work has reshaped the integration of socially relevant issues in television content, but has also ushered in an age of public health awareness in Hollywood, and outreach beyond it. Dr. Baer sat down with ScriptPhD to discuss how lessons from ER have fueled his public health efforts as a professor and founder of UCLA’s Global Media Center For Social Impact, including storytelling through public health metrics and leveraging digital technology for propelling action.

Neal Baer’s passion for social outreach and lending a voice to vulnerable and disadvantaged populations was embedded in his genetic code from a very young age. “My mother was a social activist from as long as I can remember. She worked for the ACLU for almost 45 years and she participated in and was arrested for the migrant workers’ grape boycott in the 60s. It had a true and deep impact on me that I saw her commitment to social justice. My father was a surgeon and was very committed to health care and healing. The two of them set my underlying drives and goals by their own example.” Indeed, his diverse interests and innate curiosity led Baer to study writing at Harvard and the American Film Institute and eventually, medicine at Harvard Medical School. Potentially presenting a professional dichotomy, it instead gave him the perfect niche — medical storytelling — that he parlayed into a critical role on the hit show ER.

During his seven-year run as medical advisor and writer on ER, Baer helped usher the show to indisputable influence and critical acclaim. Through the narration of important, germane storylines and communication of health messages that educated and resonated with viewers, ER‘s authenticity caught the attention of the health care community and inspired many television successors. “It had a really profound impact on me, that people learn from television, and we should be as accurate as possible,” Baer reflects. “[Viewers] believe it’s real, because we’re trying to make it look as real as possible. We’re responsible, I think. We can’t just hide behind the façade of: it’s just entertainment.” As show runner of Law & Order: SVU, Baer spearheaded a storyline about rape kit backlogs in New York City that led to a real-life push to clear 17,000 backlogged kits and established a foundation that will help other major US cities do the same. With the help of the CDC and USC’s prestigious Norman Lear Center, Baer launched Hollywood, Health and Society, which has become an indispensable and inexhaustible source of expert information for entertainment industry professionals looking to incorporate health storylines into their projects. In 2013, Baer co-founded the Global Media Center For Media Impact at UCLA’s School of Public Health, with the aim of addressing public health issues through a combination of storytelling and traditional scientific metrics.

Soda Politics

One of Baer’s seminal accomplishments at the helm of the Global Media Center was convincing public health activist Marion Nestle to write the book Soda Politics: Taking on Big Soda (And Winning). Nestle has a long and storied career of food and social policy work, including the seminal book Food Politics. Baer first took note of the nutritional and health impact soda was having on children in his pediatrics practice. “I was just really intrigued by the story of soda, and the power that a product can have on billions of people, and make billions of dollars, where the product is something that one can easily live without,” he says. That story, as told in Soda Politics, is a powerful indictment on the deleterious contribution of soda to the United States’ obesity crisis, environmental damage and political exploitation of sugar producers, among others. More importantly, it’s an anthology of the history of dubious marketing strategies, insider lobbying power and subversive “goodwill” campaigns employed by Big Soda to broaden brand loyalty.

Even more than a public health cautionary tale, Soda Politics is a case study in the power of activism and persistent advocacy. According to a New York Times expose, the drop in soda consumption represents the “single biggest change in the American diet in the last decade.” Nestle meticulously details the exhaustive, persistent and unyielding efforts that have collectively chipped away at the Big Soda hegemony: highly successful soda taxes that have curbed consumption and obesity rates in Mexico, public health efforts to curb soda access in schools and in advertising that specifically targets young children, and emotion-based messaging that has increased public awareness of the deleterious effects of soda and shifted preference towards healthier options, notably water. And as soda companies are inevitably shifting advertising and sales strategy towards , as well as underdeveloped nations that lack access to clean water, the lessons outlined in the narrative of Soda Politics, which will soon be adapted into a documentary, can be implemented on a global scale.

ActionLab Initiative

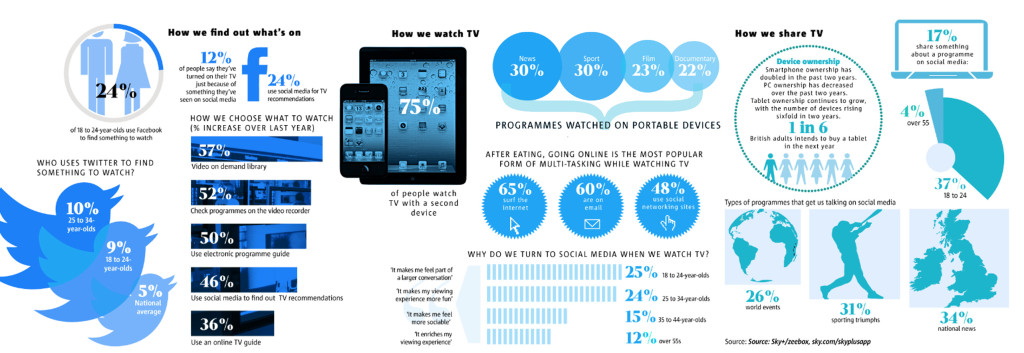

Few technological advancements have had an impact on television consumption and creation like the evolution of digital transmedia and social networking. The (fast-crumbling) traditional model of television was linear: content was produced and broadcast by a select conglomerate of powerful broadcast networks, and somewhat less-powerful cable networks, for direct viewer consumption, measured by demographic ratings and advertising revenue. This model has been disrupted by web-based content streaming such as YouTube, Netflix, Hulu and Amazon, which, in conjunction with fractionated networks, will soon displace traditional TV watching altogether. At the same time, this shifting media landscape has burgeoned a powerful new dynamic among the public: engagement. On-demand content has not only broadened access to high-quality storytelling platforms, but also provides more diverse opportunities to tackle socially relevant issues. This is buoyed by the increased role of social media as an entertainment vector. It raises awareness of TV programs (and influences Hollywood content). But it also fosters intimate, influential and symbiotic conversation alongside the very content it promotes. Enter ActionLab.

One of the critical pillars of the Global Media Center at UCLA, ActionLab hopes to bridge the gap between popular media and social change on topics of critical importance. People will often find inspiration from watching a show, reading a book or even an important public advertising campaign, and be compelled to action. However, they don’t have the resources to translate that desire for action into direct results. “We first designed ActionLab about five or six years ago, because I saw the power that the shows were having – people were inspired, but they just didn’t know what to do,” says Baer. “It’s like catching lightning in a bottle.” As a pilot program, the site will offer pragmatic, interactive steps that people can implement to change their lives, families and communities. ActionLab offers personalized campaigns centered around specific inspirational projects Baer has been involved in, such as the Soda Politics book, the If You Build It documentary and a collaboration with New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristof on his book/documentary A Path Appears. As the initiative expands, however, more entertainment and media content will be tailored towards specific issues, such as wellness, female empowerment in poor countries, eradicating poverty and community-building.

“We are story-driven animals. We collect our thoughts and our memories in story bites,” Baer notes. “We’re always going to be telling stories. We just have new tools with which to tell them and share them. And new tools where we can take the inspiration from them and ignite action.”

Baer joined ScriptPhD.com for an exclusive interview, where he discussed how his medical education and the wide-reaching impact of ER influenced his social activism, why he feels multi-media and cross-platform storytelling are critical for the future of entertainment, and his future endeavors in bridging creative platforms and social engagement.

ScriptPhD: Your path to entertainment is an unusual one – not too many Harvard Medical School graduates go on to produce and write for some of the most impactful television shows in entertainment history. Did you always have this dual interest in medicine and creative pursuits?

Neal Baer: I started out as a writer, and went to Harvard as a graduate student in sociology, [where] I started making documentary films because I wanted to make culture instead of studying it from the ivory tower. So, I got to take a documentary course, and it’s come full circle because my mentor Ed Pinchas made his last film called “One Cut, One Life” recently and I was a producer, before his demise from leukemia. That sent me to film school at the American Film Institute in Los Angeles as a directing fellow, which then sent me to write and direct an ABC after-school special called “Private Affairs” and to work on the show China Beach. I got cold feet [about the entertainment industry] and applied to medical school. I was always interested in medicine. My father was a surgeon, and I realized that a lot of the [television] work I was doing was medically oriented. So I went to Harvard Medical School thinking that I was going to become a pediatrician. Little did I know that my childhood friend John Wells, who had hired me on China Beach, would [also] hire me on “ER” by sending me the script, originally written by Michael Crichton in 1969, and dormant for 25 years until it was discovered in a trunk owned by Steven Spielberg. [Wells] asked me what I thought of the script and I said “It’s like my life only it’s outdated.” I gave him notes on how to update it, and I ultimately became one of the first doctor-writers on television with ER, which set that trend of having doctors on the show to bring verisimilitude.

SPhD: From the series launch in 1994 through 2000, you wrote 19 episodes and created the medical storylines for 150 episodes. This work ran parallel to your own medical education as a medical student, and subsequently an intern and resident. How did the two go hand in hand?

NB: I started writing on ER when I was still a fourth year medical student going back and forth to finish up at Harvard Medical School, and my internship at Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles over six years. And I was very passionate about bringing public health messages to the work that I was doing because I saw the impact that television can have on the audience, particularly the large numbers of people that were watching ER back then.

I was Noah Wylie’s character Dr. Carter. He was a third year [medical student], I was a fourth year. So I was a little bit ahead of him, and I was able to capture what it was like to be the low person on the totem pole and to reflect his struggles through many of the things my friends and I had gone through or were going through. Some of my favorite episodes we did were really drawn on things that actually happened. A friend of mine was sequestered away from the operating table but the surgeons were playing a game of world capitals. And she knew the capital of Zaire, when no one else did, so she was allowed to join the operating table [because of that]. So [we used] that same circumstance for Dr. Carter in an episode. Like you wouldn’t know those things, you had to live through them, and that was the freshness that ER brought. It wasn’t what you think doctors do or how they act but truly what goes on in real life, and a lot of that came from my experience.

SPhD: Do you feel like the storylines that you were creating for the show were germane both to things happening socially as well as reflective of the experience of a young doctor in that time period?

NB: Absolutely. We talked to opinion leaders, we had story nights with doctors, residents and nurses. I would talk to people like Donna Shalala, who was the head of the Department of Health and Human Safetey. I asked the then-head of the National Institutes of Health Harold Varmus, a Nobel Prize winner, “What topics should we do?” And he said “Teen alcohol abuse.” So that is when we had Emile Hirsch do a two-episode arc directly because of that advice. Donna Shalala suggested doing a story about elderly patients sharing perscriptions because they couldn’t afford them and the terrible outcomes that were happening. So we were really able to draw on opinion leaders and also what people were dealing with [at that time] in society: PPOs, all the new things that were happening with medical care in the country, and then on an individual basis, we were struggling with new genetics, new tests, we were the first show to have a lead character who was HIV-positive, and the triple cocktail therapy didn’t even come out until 1996. So we were able to be path-breaking in terms of digging into social issues that had medical relevance. We had seen that on other shows, but not to the extent that ER delved in.

SPhD: One of the legacies of a show like ER is how ahead of its time it was with many prescient storylines and issues that it tackled that are relevant to this very day. Are there any that you look back on that stand out to you in that regard as favorites?

NB: I really like the storyline we did with Julianna Margulies’s character [Nurse Carole Hathaway] when she opened up a clinic in the ER to deal with health issues that just weren’t being addressed, like cervical cancer in Southeast Asian populations and dealing with gaps in care that existed, particularly for poor people in this country, and they still do. Emergency rooms [treating people] is not the best way efficiently, economically or really humanely. It’s great to have good ERs, but that’s not where good preventative health care starts. The ethical dilemmas that we raised in an episode I wrote called “Who’s Happy Now?” involving George Clooney’s character [Dr. Doug Ross] treating a minor child who had advanced cystic fibrosis and wanted to be allowed to die. That issue has come up over and over again and there’s a very different view now about letting young people decide their own fate if they have the cognitive ability, as opposed to doing whatever their parents want done.

SPhD: You’ve had an Appointment at UCLA since 2013 at the Fielding School of Global Health as one of the co-founders of the Global Media Center for Social Impact, with extremely lofty ambitions at the intersection of entertainment, social outreach, technology and public health. Tell me a bit about that partnership and how you decided on an academic appointment at this time in your life.

NB: Well, I’m still doing TV. I just finished a three-year stint running the CBS series Under the Dome, which was a small-scale parable about global climate change. While I was doing that, I took this adjunct professorship at UCLA because I felt that there’s a lot we don’t know about how people take stories, learn them, use them, and I wanted to understand that more. I wanted to have a base to do more work in this area of understanding how storytelling can promote public health, both domestically and globally. Our mission at the Global Media Center for Social Impact (GMI) is to draw on both traditional storytelling modes like film, documentaries, music, and innovative or ‘new’ or transmedia approaches like Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, graphic novels and even cell phones to promote and tell stories that engage and inspire people and that can make a difference in their lives.

SPhD: One of the first major initiatives is a very important book “Soda Politics” by the public health food expert Dr. Marion Nestle. You were actually partially responsible for convincing her to write this book. Why this topic and why is it so critical right now?

NB: I went to Marion Nestle because I was convinced after having read a number of studies, particularly those by Kelly Brownell (who is now Dean of Public Policy at Duke University), that sugar-sweetened sodas are the number one contributor to childhood obesity. Just [recently], in the New York Times, they chronicled a new study that showed that obesity is still on the rise. That entails horrible costs, both emotionally and physically for individuals across this country. It’s very expensive to treat Type II diabetes, and it has terrible consequences – retinal blindness, kidney failure and heart disease. So, I was very concerned about this issue, seeing large numbers of kids coming into Children’s Hospital with Type II diabetes when I was a resident, which we had never seen before. I told Marion Nestle about my concerns because I know she’s always been an advocate for reducing the intake and consumption of soda, so I got [her] research funds from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. What’s really interesting is the data on soda consumption really aren’t readily available and you have to pay for it. The USDA used to provide it, but advocates for the soda industry pushed to not make that data easily available. I [also] helped design an e-book, with over 50 actionable steps that you can take to take soda out of the home, schools and community.

SPhD: How has social media engagement via our phones and computers, directly alongside television watching, changed the metric for viewing popularity, content development and key outreach issues that you’re tackling with your ActionLab initiative?

NB: ActionLab does what we weren’t [previously] able to do, because we have the web platforms now to direct people in multi-directional ways. When I first started on ER in 1994, television and media were uni-directional endeavors. We provided the content, and the viewer consumed it. Now, with Twitter [as an example], we’ve moved from a uni-directional to a multi-directional approach. People are responding, we are responding back to them as the content creators, they’re giving us ideas, they’re telling us what they like, what they don’t like, what works, what doesn’t. And it’s reshaping the content, so it’s this very dynamic process now that didn’t exist in the past. We were really sheltered from public opinion. Now, public opinion can drive what we do and we have to be very careful to put on some filters, because we can’t listen to every single thing that is said, of course. But we do look at what people are saying and we do connect with them in ways they never had access to us before.

This multi-directional approach is not just actors and writers and directors discussing their work on social media, but it’s using all of the tools of the internet to build a new way of storytelling. Now, anyone can do their own shows and it’s very inexpensive. There are all kinds of YouTube shows on now that are watched by many people. It’s a kind of Wild West, where anything goes and I think that’s very exciting. It’s changed the whole world of how we consume media. I [wrote] an episode of ER 20 years ago with George Clooney, where he saved a young boy in a water tunnel, that was watched by 48 million people at once. One out of six Americans. That will never happen again. So, we had a different kind of impact. But now, the media landscape is fractured, and we don’t have anywhere near that kind of audience, and we never will again. It’s a much more democratic and open world than it used to be, and I don’t even think we know what the repercussions of that will be.

SPhD: If you had a wish list, what are some other issues or global obstacles that you’d love to see the entertainment world (and media) tackle more than they do?

NB: In terms of specifics, we really need to talk about civic engagement, and we need to tell stories about how [it] can change the world, not only in micro-ways, say like Habitat For Humanity or programs that make us feel better when we do something to help others, but in a macro policy-driven way, like asking how we are going to provide compulsory secondary education around the world, particularly for girls. How do we instate that? How do we take on child marriage and encourage countries, maybe even through economic boycotts, to raise the age of child marriage, a problem that we know places girls in terrible situations, often with no chance of ever making a good living, much less getting out of poverty. So, we need to think both macroly and microly in terms of our storytelling. We need to think about how to use the internet and crowdsourcing for public policy and social change. How can we amalgamate individuals to support [these issues]? We certainly have the tools now, with Facebook, Twitter and Instagram, and our friends and social networks, to spread the word – and a very good way to spread the word is through short stories.

SPhD: You’ve enjoyed a storied career, and achieved the pinnacle of success in two very competitive and difficult industries. What drives Dr. Neal Baer now, at this stage of your life?

NB: Well, I keep thinking about new and innovative ways to use trans media. How do I use graphic novels in Africa to tell the story of HIV and prevention? How do we use cell phones to tell very short stories that can motivate people to go and get tested? Innovative financing to pay for very expensive drugs around the world? So, I’m very much interested in how storytelling gets the word out, because stories don’t just change minds, they change hearts. Stories tickle our emotions in ways that I think we don’t fully understand yet. And I really want to learn more about that. I want to know about what I call the “epigenetics of storytelling.” I’m writing a book about that, looking into research that [uncovers] how stories actually change our brain and how do we use that knowledge to tell better stories.

Neal Baer, MD is a television writer and producer behind hit shows China Beach, ER, Law & Order SVU, Under The Dome, and others. He is a graduate of Harvard University Medical School and completed a pediatrics internship at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles. A former co-chair of USC’s Norman Lear Center Hollywood, Health and Society, Dr. Baer is the founder of the Global Media Center for Social Impact at the Fielding School of Global Health at UCLA.

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development. Follow us on Twitter and Facebook. Subscribe to our podcast on SoundCloud or iTunes.

From a sci-fi and entertainment perspective, 2015 may undoubtedly be nicknamed “The Year of The Robot.” Several cinematic releases have already explored various angles of futuristic artificial intelligence (from the forgettable Chappie to the mainstream blockbuster Marvel’s Avengers: Age of Ultron to the intelligent sleeper indie hit Ex Machina), with several more on the way later this year. Two television series premiering this summer, limited series Humans on AMC and Mr. Robot on USA add thoughtful, layered (and very entertaining) discussions on the ethics and socio-economic impact of the technology affecting the age we live in. While Humans revolves around hyper-evolved robot companions, and Mr. Robot a singular shadowy eponymous cyberhacking organization, both represent enthusiastic Editor’s Selection recommendations from ScriptPhD. Reviews and an exclusive interview with Humans creators/writers Jonathan Brackley and Sam Vincent below.

Never in human history has technology and its potential reached a greater permeation of and importance in our daily lives than at the current moment. Indeed, it might even be changing the way our brains function! With entertainment often acting as a reflection of socially pertinent issues and zeitgeist motifs, it’s only natural to examine the depths to which robots (or any artificial technology) might subsume human life. Will they take over our jobs? Become smarter than us? Nefariously affect human society? These fears about the emotional lines between humans and their technology are at the heart of AMC’s new limited series Humans. It is set in the not-too-distant future, where the must have tech accessory is a ‘synth,’ a highly malleable, impeccably programmed robotic servant capable of providing any services – at the individual, family or macro-corporate level. It’s an idyllic ambition, fully realized. Busy, dysfunctional parents Joe and Laura obtain family android Anita to take care of basic housework and child rearing to free up time. Beat cop Pete’s rehabilitation android is indispensable to his paralyzed wife. And even though he doesn’t want a new synth, scientist George Millikan is thrust with a ‘care unit’ Vera by the Health Service to monitor his recovery from a stroke. They can pick fruit, clean up trash, work mindlessly in factories and sweat shops make meals, even provide service in brothels – an endless range of servile labor that we are uncomfortable or unwilling to do ourselves.

Humans brilliantly weaves the problems of this artificial intelligence narrative into multiple interweaving story lines. Anita may be the perfect house servant to Joe, but her omniscience and omnipresence borders on creepiness to wife Laura (and by proxy, the audience). Is Dr. Millikan (who helped craft the original synth technology) right that you can’t recycle them the way you would an old iPhone model? Or is he naive for loving his synth Odi like a son? And even if you create a Special Technologies Task Force to handle synth-related incidents, guaranteeing no harm to humans and minimal, if any, malfunctions, how can there be no nefarious downside to a piece of technology? They could, in theory, be obtained illegally and reprogrammed for subversive activity. If the original creator of the synths wanted to create a semblance of human life – “They were meant to feel,” he maintains – then are we culpable for their enslaved state? Should we feel relieved to see a synth break out of the brothel she’s forced to work in, or another mysterious group of synths that have somehow become sentient unite clandestinely to dream of a dimension where they’re free?

In reality, we already are in the midst of an age of artificial intelligence – computers. Powerful, fast, already capable of taking over our workforce and reshaping our society, they are the amorphous technological preamble to more specifically tailored robots, incurring all of the same trepidation and uncertainty. Mr. Robot, one of the smartest TV pilots in recent memory, is a cautionary tale about cyberhacking, socioeconomic vulnerability and the sheer reliance our society unknowingly places in computers. Its central themes are physically embodied in the central character of Elliot, a brilliant cybersecurity engineer by day/vigilante cyberhacker by night, battling schizophrenia and extreme social anxiety. To Elliott, the ubiquitous nature of computer power is simultaneously appealing and repulsive. Everything is electronic today – money, corporate transactions, even the way we communicate socially. As a hacker, he manipulates these elements with ease to get close to people and to solve injustice (carrying a Dexter-style digital cemetery of his conquests). But as someone who craves human contact he loathes the way technology has deteriorated human interaction and encouraged nameless, faceless corporate greed.

Elliot works for Allstate Security, whose biggest client is an emblem of corporate evil and economic diffidence. When they are hacked, Elliot discovers that it’s a private digital call to arms by a mysterious underground group called Mr. Robot (resembling the cybervigilante group Anonymous). They’ve hatched a plan to to concoct a wide-scale economic cyber attack that will result in the single biggest redistribution of wealth and debt forgiveness in history, and recruited Elliot into their organization. The question, and intriguing premise of the series, is whether Elliot can juggle his clean-cut day job, subversive underground hacking and protecting society one cyberterrorist act at a time, or if they will collapse under the burden of his conscience and mental illness.

Humans is a purview into the inevitable future, albeit one that may be creeping on us faster than we want it to. Even if hyper-advanced artificial intelligence is not an imminent reality and our fears might be overblown, the impact of technology on economics and human evolution is a reality we will have to grapple with eventually. And one that must inform the bioethics of any advanced sentient computing technology we create and release into the world. Mr. Robot is a stark reminder of our current present, that cyberterrorism is the new normal, that its global impact is immense, and (as with the case of artificial robots), our advancement of and reliance on technology is outpacing humans’ ability to control it.

ScriptPhD.com was extremely fortunate to chat directly with Humans writers Jonathan Brackley and Sam Vincent about the premise and thematic implications of their show. Here’s what they had to say:

ScriptPhD.com: Is “Humans” meant to be a cautionary tale about the dangers of complex artificial intelligence run amok or a hypothetical bioethical exploration of how such technology would permeate and affect human society?

Jonathan and Sam: Both! On one level, the synths are a metaphor for our real technology, and what it’s doing to us, as it becomes ever more human-like and user-friendly – but also more powerful and mysterious. It’s not so much hypothesising as it is extrapolating real world trends. But on a deeper story level, we play with the question – could these machines become more, and if so, what would happen? Though “run amok” has negative connotations – we’re trying to be more balanced. Who says a complex AI given free rein wouldn’t make things better?

SPhD: I found it interesting that there’s a tremendous range of emotions in how the humans related to and felt about their “synths.” George has a familial affection for his, Laura is creeped out/jealous of hers while her husband Joe is largely indifferent, policeman Peter grudgingly finds his synth to be a useful rehabilitation tool for his wife after an accident. Isn’t this reflective of the range of emotions in how humans react to the current technology in our lives, and maybe always will?

J&S: There’s always a wide range of attitudes towards any new technology – some adopt enthusiastically, others are suspicious. But maybe it’s become a more emotive question as we increasingly use our technology to conduct every aspect of our existence, including our emotional lives. Our feelings are already tangled up in our tech, and we can’t see that changing any time soon.

SPhD: Like many recent works exploring Artificial Intelligence, at the root of “Humans” is a sense of fear. Which is greater – the fear of losing our flaws and imperfections (the very things that make us human) or the genuine fear that the sentient “synths” have of us and their enslavement?

J&S: Though we show that synths certainly can’t take their continued existence for granted, there’s as much love as fear in the relationships between our characters. For us, the fear of how our technology is changing us is more powerful – purely because it’s really happening, and has been for a long time. But maybe it’s not to be feared – or not all of it at least…

Catch a trailer and closer series look at the making of Humans here:

And catch the FULL first episode of Mr. Robot here:

Mr. Robot airs on USA Network with full episodes available online.

Humans premieres on June 28, 2015 on AMC Television (USA) and airs on Channel 4 (UK).

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development. Follow us on Twitter and Facebook. Subscribe to our podcast on SoundCloud or iTunes.

“It’s like a war. You don’t know whether you’re going to win the war. You don’t know if you’re going to survive the war. You don’t know if the project is going to survive the war.” The war? Cancer, still one of the leading causes of death despite 40 years passing since the National Cancer Act of 1971 catapulted Richard Nixon’s famous “War on Cancer.” The speaker of the above quote? A scientist at Genentech, a San Francisco-based biotechnology and pharmaceutical company, describing efforts to pursue a then-promising miracle treatment for breast cancer facing numerous obstacles, not the least of which was the patients’ rapid illness. If it sounds like a made-for-Hollywood story, it is. But I Want So Much To Live is no ordinary documentary. It was commissioned as an in-house documentary by Genentech, a rarity in the staid, secretive scientific corporate world. The production values and storytelling offer a tremendous template for Hollywood filmmakers, as science and biomedical content become even more pervasive in film. Finally, the inspirational story behind Herceptin, one of the most successful cancer treatments of all time, offers a testament and rare insight to the dedication and emotion that makes science work. Full story and review under the “continue reading” cut.

For biotechnology and pharmaceutical companies, it is the best of times, it is the worst of times. On the one hand, many people consider this a Golden Era of pharmaceutical discovery and innovation for certain illnesses like cancer. Others, such as HIV, receive poor grades for drug and vaccine development. Furthermore, the FDA recently passed much more stringent controls on drugs brought to market, leaving some to posit that this will have a negative impact on future pharmaceutical breakthroughs. And while a recent documentary chronicles some of the unhealthy profits of the pharmaceutical industry, the enormous cost of developing and bringing medicines to market is often gravely overlooked. Today, the pharmaceutical industry as a whole has one of the lowest favorability scores of any major industry, despite some impressive social contributions, partnerships and global health investments. Much of this public hostility simply comes down to the fact that people don’t know very much about the pharmaceutical industry, notoriously reluctant to publicize or reveal anything about their inner workings.

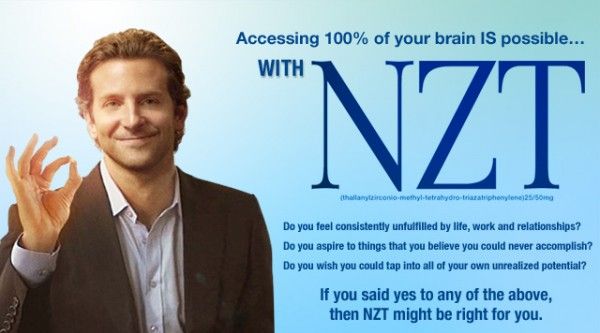

Science in Hollywood is experiencing no such crisis. In many ways, it is a golden age for science, technology and medicine in film, with more big-budget mainstream films exploring themes and content germane to 21st Century science than ever before. Last year alone, three smart hit movies broached the realities, hopes and anxiety of the technological times we live in, each in a very different way. The stylish and ambitious thriller Limitless explored the possibility of a limitless brain capacity through pharmacopeia, a magical pill that would maximize one’s intelligence and allow 100% brain function around the clock. Certainly echoing the credo of the modern pharmaceutical movement—there is a pill that can solve every problem, whether it’s been invented or not—Limitless fell slightly short in condemning (or even properly acknowledging) the impracticalities ethical irresponsibility of developing such a drug, especially in its ending. Stephen Soderbergh’s surgical and pinpoint-accurate epic Contagion gave audiences a spine-chilling, terrorizing purview into the medical and public health realities of a modern-day pandemic. But while it strove, and succeeded, in showcasing how government agencies, university labs and medical establishments would contend with and fight off such a global disaster, Contagion was never able to connect audiences emotionally either with the characters impacted by the pandemic or with the scientists battling it. No recent movie is a better example of delicate introspection and exposition than the brilliant, poignant, funny and difficult 50/50. On the heels of CNN pondering whether Hollywood could take on cancer came a film that did so with reality, grace and even humor. Partially because it was based on screenwriter Will Reiser’s own brush with cancer, 50/50 set aside the clinical as a secondary backdrop to examine the psychological.

Each of the films above has an important quality that is be an essential component to effective Hollywood science storytelling – scientific accuracy, emotional connection to the outside world and an overview of biomedical impact and innovation. We recently screened an industry documentary, filmed at the request of Genentech scientists, called I Want So Much To Live, that is an excellent blueprint for the way we’d like to see scientific stories portrayed in film. Best of all, it doesn’t sacrifice the human story for the technical one, nor the very real complex emotions that scientists, engineers and doctors feel when they develop and market potentially life-saving technology.

The miracle of Herceptin is really a decade-long journey that started in the labs of UCLA, moved to the pharmaceutical labs of San Francisco, endured countless obstacles, street riots and controversies to end up as one of the most revolutionary breakthroughs in breast cancer treatment research history. Advances in cancer insight always seem to come in evolutionary leaps. For example, the cellular mechanism of how normal cells become cancerous was unknown until Harold Varmus and Michael Bishop established the presence of retroviral oncogenes, genes that control cellular growth and replication. When either disrupted or turned on, these genes contribute to the transformation of normal cells into tumors. Other than the discovery of as an anti-estrogen treatment for breast cancers, relatively little new ground had been gained in fighting the disease. Scientists continued to be perplexed why some women were cured by chemotherapy, which tries to stop cancer cell division by attacking the most rapidly-dividing cells in the body, while others didn’t respond at all. It was not until the late 80s that scientists Alex Ullrich and Michael Shepherd (both featured in the film) discovered that about 20-30% of early-stage breast cancers express amplify a gene called HER-2, a protein embedded in the cell membrane that helps regulate cell growth and signaling. With the help of UCLA scientist Dennis Slamon, famously portrayed by Harry Connick, Jr. in a made-for-TV movie about the development of Herceptin, the scientists soon developed an anti-HER-2 antibody that significantly slowed tumor growth.

An early Phase I clinical trial was conducted simply to establish safety, with 20 volunteers. The lone survivor, still alive to this day, was given 10 weeks to live. Phase II trials honed in on dosage and establishing that the drug performed its intended effects. This time, out of 85 volunteers, 5 survived completely, not a bad result, but not enough for the FDA and the science community. The scientists took a huge risk for their Phase III study. They combined their anti-HER-2 antibody with current treatment. The results were astounding. Out of 450 patients, 50% survived — the highest ever success rate for metastatic cancer!

Think the story ends here? Think again. This is where it just begins to take more emotional twists and turns than a fictitious Hollywood script. Unlike many Hollywood productions, though, the human impact angle was shared equally between all the players in this evolving story, easily this documentary’s most powerful aspect. In order to test their Phase III trials of Herceptin (in concert with chemotherapy treatments available at that time), Genentech had to establish a highly controversial lottery system to pick those who would receive highly limited life-saving quantities of Herceptin, and those who would be categorized in the control studies, and thereby handed a death sentence. So controversial was the lottery system, that it engendered televised protests in the Bay Area, along with anguished pleas from dying patients—the documentary’s title is the first sentence of one such letter: “I want so much to live.” The scientists at Genentech were hardly immune to the weight of each decision, either. They were tormented over the fairness of the lottery system, producing enough high-quality treatment to pass the clinical trial, and even in keeping an unbiased eye on the science to save lives in the long run. Talking about the pressure of those days reduced one of the scientists to tears. And after all was said and done, the lone FDA scientist entrusted with the power to oversee the Herceptin study and green light its approval as a drug? She had just lost her mother to breast cancer. These intertwining fortunes are summarized by executive producer Christie Castro: “By definition, groups of people are imperfect. But those who worked on Herceptin proved that the complexity – indeed, the fantastic mess – that simply comes with being human can sometimes result in something truly worthwhile.”

One of the first patients to get the experimental Herceptin treatment prior to FDA approval, though not profiled in the movie, is flourishing well over a decade after being diagnosed with the most aggressive form of breast cancer. Stories like hers lie at the emotional heart of the I Want So Much To Live story (and Genentech’s motivation for continuing the controversial studies):

Herceptin was officially approved as a drug on September 22, 2000. On October 20, 2010, Herceptin was approved as an adjuvant (joint) treatment with current chemotheraphy drugs for the treatment of aggressive breast cancer. To date, the adjuvant therapy has had an impressive 58% success rate for a cancer that once carried an unlikely rate of survival for those afflicted.

Take a look at the trailer for I Want So Much To Live:

The powerful and well-crafted content of this documentary should serve as a valuable template for how the multi-faceted power of storytelling can be used across multiple industries. It smartly tells a gripping scientific story without either dumbing down the science or elevating it beyond a layperson’s understanding—a certain goal for the increasing amount of cinematic fare such as Contagion. It provides a functional breakdown of the enormous challenges and technical obstacles of the pharmaceutical drug development process. Like many other aspects of science, it is mysterious to the general public, out of their grasp and seemingly always occuring behind closed doors. Especially at a time when public perception of the pharmaceutical industry is at an all-time low, such transparency could strengthen reputations and increase business. “Corporations are,” executive producer Christine Castro reminds us, “groups of people who have ideas, ambitions, conflicts and dreams, and, at the end of the day, a desire to see their work result in something meaningful. That’s why we decided to take a creative chance and face the potential skepticism that a corporation would or could tell an unvarnished story about itself.”

Finally, the film develops a three-dimensional emotional tether to the three different sides impacted by the scientific process: scientists, the agencies that regulate them and society as a whole. There doesn’t always have to be a tacit bad guy, and sometimes, this protagonistic complexity makes for the best story of all. Holder, who started filming I Want So Much To Live around the same time that her late brother was diagnosed with a rare and virulent form of cancer, echoed our sentiment as she reflected on the process of making the film. It allowed her to discover “that science is a creative pursuit as well as a technical one; that science is beautiful and can be accessible; and that anyone, at any time, might have the idea that could one day save lives.”

We can only hope that the harmony of creativity, passion and emotion devoted to all sides of the drug discovery process within this film translates to more private and studio productions dealing with complex scientific and socio-technological issues.

ScriptPhD.com caught up with filmmaker Elizabeth Holder, who directed and produced I Want So Much To Live. Here are some of her thoughts on putting together this incredible story and interacting with the scientists and heroic patients that made it happen:

ScriptPhD.com: Can you tell me where the seeds of inspiration for the story of the drug Herceptin first arose, and what inspired you to tackle this material for your documentary?

Elizabeth Holder: The initial idea to make a documentary film about Herceptin came from executive producer Chris Castro, who upon joining Genentech in 2007 thought that the story would make a compelling documentary film. (She will have to share with you her experience.) I first heard about the project from a friend and began doing research on Herceptin and Genentech. I was excited to work on this film; excited to jump into and explore a new world. My first inspiration came from the people who were the story; the passionate men and women who faced adversity with courage and perseverance, never swaying from their pursuit, making difficult decisions laced with moral and ethical ramifications. I knew this story of individual and collective growth would resonate with many, and would be especially poignant to the employees of Genentech. (This at the time was the intended audience for the film.) When I began working on this film in 2008 I had no idea how personal this journey would become and how connected I would be to the people I would meet and the story I was going to tell.

While I was making the film, my younger brother David was battling cancer – a rare type of cancer for a 33 year old man. While I was meeting with scientists and learning about biotech and drug development for the movie, David was fighting the disease with everything science and medicine could offer. He wrote a blog about his journey, signing off each entry with the words “Plow On”. Each day, I would hope that the scientists would hurry up. Figure it out. But I learned firsthand that science is not a “hurry up” business and that many people are doing everything they can to find ways to stop cancer. My wish is that the film serves to inspire everyone who is on the frontlines in the battle against cancer, to encourage them to keep on fighting the good fight, no matter what, and even on a bad day, to Plow On.

SPhD: How willing were the patients and scientists to contribute to the project?

EH: As you can imagine, everyone, especially scientists, are skeptical. Some people took a bit more convincing than others, but once they started talking, the interviews, both on and off camera, were amazing.

I am grateful to the patients, scientists, activists, executives, and doctors for honestly and enthusiastically sharing their stories, perspective, and experience with me. I quickly became indebted to mentors and colleagues who diligently and without judgment explained and re-explained molecular biology and the drug development process to me. I hope the determination and delight in which they approach their work is reflected in the film.

SPhD: Any of your own preconceived notions that were shattered or altered throughout the making of this film?

EH: I discovered striking similarities between scientists and filmmakers which I did not expect to find. A research scientist and a filmmaker must each imagine an idea, convince others to recognize the value of funding the idea, and then prove the concept. Like many filmmakers, the scientists I met were impassioned about their work and showed great determination in the face of extraordinary odds. Like filmmaking, drug development takes a village. Before making this film I had no idea how many years and how many people it took to develop a drug; the process involves a huge collaborative effort between massive numbers of people in multiple organizations, in various countries.

It was incredible and amazing to me that the scientists would talk about “cells” and “exxons” and “nucleotides” as if they could actually be seen by the human eye. It was also inspiring to me that a scientist is committed enough to work on a research project for their whole career with the knowledge that they might not ever see an outcome in their lifetime. And finally, I was pleased to confirm (though not statistically proven) that a lot of really smart and accomplished people do not have perfectly clean desks.

SPhD: Within the movie, we get a real feel for the dichotomy between the emotional appeals of the desperately ill patients, the cautious, careful FDA scientists, and the Genentech researchers who want to make sure the product they introduce is safe for patients. Was this a thematic element you foresaw or that developed as you pieced the film together?

EH: I carefully planned out the film, yet also left room for new discoveries along the way. (I was constantly learning – from each filmed interview, from advisors, from books.) For each defining moment in the film I made sure to film at least three people talking about the same experience with different opinions. I wanted to make sure that the topic was covered from various perspectives so I could intercut interviews together. I knew that I was not going to use narration. I only wanted people who were part of the story to be telling the story; to engage the audience with their firsthand accounts. I wanted the audience to feel connected emotionally to each person in the film, to empathize with the person on screen even if they disagreed with their tactic and/or goal. Additionally, I knew I was going to use archival footage, photos and authentic documents to organically reveal the isolation and miscommunication, the unwitting partnerships, the building mistrust and the eventual coming together. When I first saw and read the pile of letters saved by Geoff, I knew that I would use it in the film. I carried a few of those letters with me to every interview and pulled them out when it felt right, asking people to read them and respond. The scene was assembled to show how incorrect assumptions lead to strife; to show how each person’s journey was critical to the whole story; and to show how those intertwining stories eventually became the framework for the work that is continuing today.

SPhD: What are your own thoughts on the lottery system that Genentech ultimately used to determine who would be eligible to participate in the Herceptin clinical trials?

EH: I see both sides of the issue, and don’t think there is an easy answer. When interviewing people for this film, I went into each interview with a clean slate, without having any pre-conceived agenda or opinion. It was critical that I empathized with each person and was able to tell the story though the objectives and needs of those who I interviewed, those who had direct experience. I needed to be able to fully see and feel the situation from their point of view. And, to me, judgment is only something that pulls us apart, not together. I am thankful I am in the documentary business and not in the business of making the kind of decisions that had to be made during that time. I am not sure what I would have done if someone I loved needed the drug before it was approved.

~*ScriptPhD*~

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development.

Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

]]>

As far back as last summer, when pilots for the current television season were floating around, a quirky sci-fi show for NBC called Awake caught our eye as the best of the lot. Camouflaged in a standard procedural cop show is an ambitious neuroscience concept—a man living in two simultaneous dream worlds, either of which (or neither of which) could be real. We got a look at the first four episodes of the show, which lay a nice foundation for the many thought-provoking questions that will be addressed. We review them here, as well as answering some questions of our own about the sleep science behind the show with UCLA sleep expert Dr. Alon Avidan.

Detective Michael Britten (Jason Isaacs) is a middle class police officer living in Los Angeles, with a lovely wife and teenage son, a virtual ‘everyman’ until an unspeakable tragedy—in the show’s opening moments—transform him into a paranormal dual existence. A violent car accident kills at least one member of his family, possibly both (the audience doesn’t yet know, and neither does Britten). Except instead of mourning the loss and moving on, Britten begins a bifurcated dream existence, where in one state, his wife Hannah (Laura Allen) is alive and his son Rex (Dylan Minnette) has perished, and as soon as he wakes up, the opposite is true. Complicating matters further is the mirroring of his lives on each end of this sleep-wake spectrum state. In his ‘single father’ widower existence, he is partnered with gruff police veteran Isaiah Freeman (Steve Harris), and works with no-nonsense therapist Dr. Judith Evans (Cherry Jones). In his other existence, mourning

the loss of his son with his wife, Britten’s Captain (Laura Innes) has partnered him with rookie Efrem Vega (Wilmer Valderama), as he works things through with kind, objective therapist Dr. John Lee (BD Wong).

Juggling two worlds might seem complicated (and exhausting) enough, but life for Detective Britten gets even more muddled. Soon sliding with regularity between his two new worlds, he takes various clues from one to solve crimes in the other, even as his behavior in both becomes more erratic and precarious. And while the pilot flawlessly establishes the landscape of Britten’s new reality, future episodes will slowly chip away at it, leaving the viewers with many unanswered questions and mysteries. Is Britten simply dreaming one of these worlds? If so, which is his ‘true’ reality? Is either? Could they both be a lucid dream? Could it be that both his wife and son died? And while later episodes can sometimes veer a bit too much into standard procedural fare, they also offer a thunderbolt of a plot point, suggesting that the car crash that took Britten’s family may have been no accident at all. Given how quickly the last truly ambitious network sci-fi drama (Heroes) veered into absurdity, the steady pacing and erudite plot development of Awake is an almost welcome relief.

We look forward to dreaming for many episodes to come.

Catch up with what you may have missed with this extended trailer:

The sleep science behind the thought-provoking concept of Awake excited us a lot, but we wanted to get deeper answers to some of our most basic questions about the neuroscience of sleep, and just what it is that Michael Britten might be suffering from. To do so, ScriptPhD.com sat down with Dr. Alon Yosefian Avidan, the Director of the Sleep Disorders Laboratory at UCLA’s Department of Neurology.

ScriptPhD.com: Dr. Avidan, for people reading this that may not know very much at all about sleep science, can you give us a brief layperson’s overview of what the scientific consensus is on what sleep is for, exactly?