History abounds with examples of unsung science heroes, researchers and visionaries whose tireless efforts led to enormous breakthroughs and advances, often without credit or lasting widespread esteem. This is particularly true for women and minorities, who have historically been under-represented in STEM-related fields. English mathematician Ada Lovelace is broadly considered the first great tech and computing visionary — she pioneered computer programming language and helped construct what is considered the first computing machine (the Babbage Analytical Engine) in the mid-1800s. Physical chemist Dr. Rosalind Franklin performed essential X-ray crystallography work that ultimately revealed the double-helix shape of DNA (Photograph 51 is one of the most important images in the history of science). Her work was shown (without her permission) to rival King’s College biology duo Watson and Crick, who used the indispensable information to elucidate and publish the molecular structure of DNA, for which they would win a Nobel Prize. Dr. Percy Julian, a grandson of slaves and the first African-American chemist ever elected to the National Academy of Sciences, ingeniously pioneered the synthesis of hormones and other medicinal compounds from plants and soybeans. New movie Hidden Figures, based on the exhaustively researched book by Margot Lee Shetterley, tells the story of three such hitherto obscure heroes: Katherine Johnson, Dorothy Vaughn and Mary Jackson, standouts in a cohort of African-American mathematicians that helped NASA launch key missions during the tense 19060s Cold War “space race.” More importantly, Hidden Figures is a significant prototype for purpose-driven popular science communication — a narrative and vehicle for integrated multi-media platforms to encourage STEM diversity and scientific achievement.

The participation of women in astrophysics, space exploration and aeronautics goes back to the 1800s at the Harvard College Observatory, as chronicled by Dava Sobell in The Glass Universe, a companion book to Hidden Figures. These women, every bit as intellectually capable and scientifically curious as their male counterparts, took the only opportunity afforded to them, as human “computers,” literally calculating, measuring and analyzing the classification of our universe. By the 1930s, the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, a precursor that would be subsumed by the creation of NASA in 1958, hired five of these female computers for their Langley aeronautical building in Hampton, Virginia. Shortly after World War II, with the expansion of the female workforce and war fueling innovation for better planes, NACA began hiring college-educated African American female computers. They were segregated to the Western side of the Langley campus (referred to as the “West Computers”), and were required to use separate bathroom and dining facilities, all while being paid less to do equal work as their white counterparts. Many of these daily indignities were chronicled in Hidden Figures. By the 1960s, the Space Program at NASA was defined by the two biggest sociopolitical events of the era: the Cold War and the Civil Rights Movement. Embroiled in an anxious race with Soviet astronauts to launch a man in orbit (and eventually, to the Moon), NASA needed to recruit the brightest minds available to invent seemingly impossible math to make the mission possible. Katherine Goble (later Johnson), was one of those minds.

Katherine Johnson (portrayed by Taraji P. Henson) was a math prodigy. A high school freshman by the time she was 10 years old, Johnson’s fascination with numbers led her to a teaching position, and eventually, as a human calculator at the Langley NASA facility. Hand-picked to assist the Space Task Group, portrayed in the movie as Al Harrison (Kevin Costner), a fictionalized amalgamation of three directors Johnson worked with in her time at NASA, she had to traverse institutionalized racism, sexism and antagonistic collaborators in her path. Johnson would go on to calculate trajectories that sent both Alan Shepard and John Glenn into space, as well as key data for the Apollo Moon landing. Supporting Johnson are her good friends and fellow NASA colleagues Dorothy Vaughan (Octavia Spencer) and Mary Jackson (Janelle Monáe). Vaughan herself was a NASA pioneer, becoming the first black computing section leader and IBM FORTRAN programming expert. Jackson became the first black engineer at NASA, getting special permission to take advanced math courses in a segregated school.

Katherine Johnson’s legacy in science, mathematics, and civil rights cannot be understated. Current NASA chief Charles Bolden thoughtfully paid tribute to the iconic role model in Vanity Fair. “She is a human computer, indeed, but one with a quick wit, a quiet ambition, and a confidence in her talents that rose above her era and her surroundings,” he writes. The Langley NASA facility where she broke barriers and pioneered discovery honored Johnson by dedicating the building in her name last May. Late in 2015, Johnson was bestowed with a Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Barack Obama.

Featured prominently in Hidden Figures, technology giant IBM has had a long-standing relationship with NASA ever since the IBM 7090 became the first computing mainframe to be used for flight simulations, with the iconic System/360 mainframe engineering the Apollo Moon landing. Although IBM mainframes are no longer in use for mathematical calculations at NASA, they are partnering through the use of artificial intelligence for space missions. IBM Watson has the capability to sift through thousands of pages of information to get pilots critical data in real time and even monitor and diagnose astronauts’ health as a virtual/intelligence agent.

More importantly, IBM is taking a leadership role in developing STEM outreach education programs and a continued commitment to diversifying the technology workforce for the demands of the 21st Century. 50 years after Katherine Johnson’s monumental feats at NASA, the K-12 achievement gap between white and black students has barely budged. Furthermore, a 2015 STEM index analysis shows that even as the number of STEM-related degrees and jobs proliferates, deeply entrenched gaps between men and women, and an even wider gap between whites and minorities, remain in obtaining STEM degrees. This is exacerbated in the STEM work force, where diversity has largely stalled and women and minorities remain deeply under-represented. And yet, technology companies will need to fill 650,000 new STEM jobs (the fastest growing sector) by 2018, with the highest demand overall for so-called “middle-skill” jobs that may only require technical or community college preparation. Launched in 2011 by IBM, in collaboration with the New York Department of Education, P-TECH is an ambitious six-year education model predominantly aimed at minorities that combines college courses, internships and mentoring with a four year high school education. Armed with a combined high school and associates’ degree, these students would be immediately ready to fill high-tech, diverse workforce needs. Indeed, IBM’s original P-TECH school in Brooklyn has eclipsed national graduation rates for community college degrees over a two-year period, with the technology company committing to widely expanding the program in the coming years. Technology companies becoming stakeholders in, and even innovators of, educational models and partnerships can have profound impacts in innovation, economic growth and diminishing poverty through opportunity.

Dovetailing with the release of Hidden Figures, IBM has also partnered with The New York Times to launch their first augmented reality experience. Combining advocacy, outreach and data mining, the free, downloadable app called “Outthink Hidden” combines the inspirational stories portrayed in Hidden Figures with digitally-interactive content to create a PokemonGo-style nationwide hunt about STEM figures, historical leaders, places and areas of research across the country. The app can be used interactively at 150 locations in 10 U.S. cities, STEM Centers (such as NASA Langley Research Center and Kennedy Space Center) and STEM Universities to learn not just about the three mathematicians featured in Hidden Figures, but also other diverse STEM pioneers. Coupled with the powerful wide impact of Hollywood storytelling and a complimentary book release, “Outthink Hidden” could be an important prototype for engaging young tech-savvy students, possibly even in organized, classroom environments, and promoting interest in exploring STEM education, careers and mentorship opportunities.

There are no easy solutions for reforming STEM education or diversifying the talent pool in research labs and technology companies. But we can provide compelling narrative through movies and TV shows, and, increasingly, digital content. Perhaps the first step to inspiring and cultivating the next Katherine Johnson is simply to start by telling more stories like hers.

View a trailer for Hidden Figures:

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development. Follow us on Twitter and Facebook. Subscribe to our podcast on SoundCloud or iTunes.

From its earliest inceptions, science fiction has blurred the line between reality and technological fantasy in a remarkably prescient manner. Many of the discoveries and gadgets that have integrated seamlessly into modern life were first preconceived theoretically. More recently, the technologies behind ultra-realistic visual and motion capture effects are simultaneously helping scientists as research tools on a granular level in real time. The dazzling visual effects within the time-jumping space film Interstellar included creating original code for a physics-based ultra-realistic depiction of what it would be like to orbit around and through a black hole. Astrophysics researchers soon utilized the film’s code to visualize black hole surfaces and their effects on nearby objects. Virtual reality, whose initial development was largely rooted in imbuing realism into the gaming and video industries, has advanced towards multi-purpose applications in film, technology and science. The Science Channel is augmenting traditional programming with a ‘virtual experience’ to simulate the challenges and scenarios of an astronaut’s journey into space; VR-equipped GoPro cameras are documenting remote research environments to foster scientific collaboration and share knowledge; it’s even being implemented in health care for improving training, diagnosis and treatment concepts. The ability to record high-definition film of landscapes and isolated areas with drones, which will have an enormous impact on cinematography, carries with it the simultaneous capacity to aid scientists and health workers with disaster relief, wildlife conservation and remote geomapping.

The evolution of entertainment industry technology is sophisticated, computationally powerful and increasingly cross-functional. A cohort of interdisciplinary researchers at Northwestern University is adapting computing and screen resolution developed at DreamWorks Animation Studios as a vehicle for data visualization, innovation and producing more rapid and efficient results. Their efforts, detailed below, and a collective trend towards integration of visual design in interpreting complex research, portends a collaborative future between science and entertainment.

Not long into his tenure as the lead visualization engineer at Northwestern University’s Center For Advanced Molecular Imaging (CAMI), Matt McCrory noticed a striking contrast between the quality of the aesthetic and computational toolkits used in scientific research versus the entertainment industry. “When you spend enough time in the research community, with people who are doing the research and the visualization of their own data, you start to see what an immense gap there is between what Hollywood produces (in terms of visualization) and what research produces.” McCrory, a former lighting technical director at DreamWorks Animation, where he developed technical tools for the visual effects in Shark Tale, Flushed Away and Kung Fu Panda, believes that combining expertise in cutting-edge visual design with emerging tools of molecular medicine, biochemistry and pharmacology can greatly speed up the process of discovery. Initially, it was science that offered the TV and film world the rudimentary seeds of technology that would fuel creative output. But the TV and film world ran with it — so much so, that the line between science and art is less distinguishable than in any other industry. “We’re getting to a point [on the screen] where we can’t discern anymore what’s real and what’s not,” McCrory notes. “That’s how good Hollywood [technology] is getting. At the same time, you see very little progress being made in scientific visualization.”

What is most perplexing about the stagnant computing power and visualization in science is that modern research across almost all fields is driven by extremely large, high-resolution data sets. A handful of select MRI imaging scanners are now equipped with magnets ranging from 9.4 to 11.75 Teslas, capable of providing cellular resolution on the micron scale (0.1 to 0.2 millimeters versus 1.5 Tesla hospital scanners, at 1 millimeter resolution) and cellular changes on the microsecond scale. The ultra high-resolution imaging provides researchers with insight into everything from cancer to neurodegenerative diseases. While most biomedical drug discovery today is engineered by robotics equipment, which screens enormous libraries of chemical compounds for activity potential around the clock in a “high-throughput” fashion — from thousands to hundreds of thousands of samples — data must still be analyzed, optimized and implemented by researchers. Astronomical observations (from black holes to galaxies colliding to detailed high-power telescope observations in the billions of pixels) produce some of the largest data sets in all of science. Molecular biology and genetics, which in the genomics era has unveiled great potential for DNA-based sub-cellular therapeutics, has also produced petrabytes of data sets that are a quandary for most researchers to store, let alone visualize.

Unfortunately, most scientists can’t allocate dual resources to both advancing their own research and finding the best technology with which to optimize it. As McCrory points out: “In a field like chemistry or biology, you don’t have people who are working day and night with the next greatest way of rendering photo-realistic images. They’re focused on something related to protein structures or whatever their research is.”

The entertainment industry, on the other hand, has a singular focus on developing and continuously perfecting these tools, as necessitated by proliferation of divergent content sources, screen resolution and powerful capture devices. As an industry insider, McCrory appreciates the competitive evolution, driven by an urgency that science doesn’t often have to grapple with. “They’ve had to solve some serious problems out there and they also have to deal with issues involving timelines, since it’s a profit-driven industry,” he notes. “So they have to come up with [computing] solutions that are purely about efficiency.” Disney’s 2014 animated science film Big Hero 6 was rendered with cutting-edge visualization tools, including a 55,000-core computer and custom proprietary lighting software called Hyperion. Indeed, render farms at LucasFilm and Pixar consist of core data centers and state-of-the-art supercomputing resources that could be independent enterprise server banks.

At Northwestern’s CAMI, this aggregate toolkit is leveraged by scientists and visual engineers as an integrated collaborative research asset. In conjunction with a senior animation specialist and long-time video game developer, McCrory helped to construct an interactive 3D visualization wall consisting of 25 high-resolution screens that comprise 52 million total pixels. Compared to a standard computer (at 1-2 million pixels), the wall allows researchers to visualize and manage entire data sets acquired with higher-quality instruments. Researchers can gain different perspectives on their data in native resolution, often standing in front of it in large groups, and analyze complex structures (such as proteins and DNA) in 3D. The interface facilitates real-time innovation and stunning clarity for complex multi-disciplinary experiments. Biochemists, for example, can partner with neuroscientists to visualize brain activity in a mouse as they perfect drug design for an Alzheimer’s enzyme inhibitor. Additionally, 7 thousand in-house high performing core servers (comparable to most studios) provide undisrupted big data acquisition, storage and mining.

Could there be a day where partnerships between science and entertainment are commonplace? Virtual reality studios such as Wevr, producing cutting-edge content and wearable technology, could become a go-to virtual modeling destination for physicists and structural chemists. Programs like RenderMan, a photo-realistic 3D software developed by Pixar Animation Studios for image synthesis, could enable greater clarity on biological processes and therapeutics targets. Leading global animation studios could be a source of both render farm technology and talent for science centers to increase proficiency in data analysis. One day, as its own visualization capacity grows, McCrory, now pushing pixels at animation studio Rainmaker Entertainment, posits that NUViz/CAMI could even be a mini-studio within Chicago for aspiring filmmakers.

The entertainment industry has always been at the forefront of inspiring us to “dream big” about what is scientifically possible. But now, it can play an active role in making these possibilities a reality.

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development. Follow us on Twitter and Facebook. Subscribe to our podcast on SoundCloud or iTunes.

Dr. Kevin Grazier has made a career of studying intergalactic planetary formation, and, over the last few years, helping Hollywood writers integrate physics smartly into storylines for popular TV shows like Battlestar Galactica, Eureka, Defiance and the blockbuster film Gravity. His latest book, Hollyweird Science: From Quantum Quirks to the Multiverse traverses delightfully through the science-entertainment duality as it first breaks down the portrayal of science in movies and television, grounding the audience in screenplay lexicon, then elucidates a panoply of physics and astronomy principles through the lens of storylines, superpowers and sci-fi magic. With the help of notable science journalist Stephen Cass, Hollyweird Science is accessible to the layperson sci-fi fan wishing to learn more about science, a professional scientist wanting to apply their knowledge to higher-order examples from TV and film or Hollywood writers and producers of future science-based materials. From case studies, to in-depth interviews to breaking down the Universe and its phenomena one superhero and far-away galaxy at a time, this first volume of an eventual trilogy is the essential foundation towards understanding how science is integrated into a story and ensuring that future TV shows and movies do so more accurately than ever before. Full ScriptPhD review and podcast with author and science advisor Dr. Grazier below.

Most people who watch movies and TV shows never went to film school. They are not familiar with the intricacies of three-act structure, tropes, conceits and MacGuffins that are the skeletal framework of a standard storytelling toolkit. Yet no genre is more rooted in and dependent on setup and buying into a payoff than sci-fi and films conceptualized in scientific logic. Many, if not most, critiques of science in entertainment don’t fully acknowledge that integrating abstruse science/technology with the complex constraints of time, length, character development and screenplay format is incredibly demanding. Hollyweird Science does point out some egregious examples of “information pollution” and the “Hollywood Curriculum Cycle” – the perpetuation bad, if not fictitious, science. But after grounding the reader in a primer of the fundamental building blocks of movie-making and TV structure, not only is there a more positive, forgiving tone in breaking down the history of the sci-fi canon (some of which predicted many of the technological gadgets we enjoy today), but even a celebration of just how much and how often Hollywood gets the science right.

Conversely, the vast majority of Hollywood writers, producers and directors don’t regularly come across PhD scientists in real life, and have to form impressions of doctors, scientists and engineers based on… other portrayals in entertainment. Scientists, after all, represent only 0.2 percent of the U.S. population as a whole, and less than 700,000 of all jobs belong to doctors and surgeons. And while these professions are amply represented on screen in number, that’s not necessarily been the case in accuracy. The insular self-reliance of screenwriters on their own biases has led to stereotyping and pigeonholing of scientists into a series of familiar archetypes (nerds, aloof omniscient sidekicks), as Grazier and Cass take us through a thorough, labyrinthine archive of TV and movie scientists. But as scientists have become more involved in advising productions, and have become more prominent and visible in today’s innovation-driven society, their on screen counterparts have likewise become a more accurate reflection of these demographics – mainstream hits like The Big Bang Theory, CSI (and its many procedural spinoffs), Breaking Bad and films like Gravity, The Martian, Interstellar and The Imitation Game are just a recent sampling.

If you’re going to teach a diverse group of readers about the principles of physics, astronomy, quantum mechanics and energy forms, it’s best to start with the basics. Even if you’ve never picked up a physics textbook, Hollyweird Science provides a fundamental overview of matter, mass, elements, energy, planet and star formation, time, radiation and the quantum mechanics of universe behavior. More important than what these principles are, Grazier discerns what they are not, with running examples from iconic television series, movies and sci-fi characters. What exactly is the difference between weight and mass and force, per the opening scene of the film Gravity? How are different forms of energy classified? Are the radioactive giants of Godzilla and King Kong realistic? What exactly happens when Scotty is beamed up? Buoying the analytical content are a myriad of interviews with writers and producers, expounding honestly about working with scientists, incorporating science into storytelling and where conflicts arose in the creative process.

People who want to delve into more complex science can do so through “science boxes” embedded throughout the book – sophisticated mathematical and physics analyses of entertainment staples, trivial and significant. Among my favorites: why Alice in Wonderland is a great example of allometric scaling, the thermal radiation of cinematography lighting, hypothesizing Einsteinian relativity for the Back To The Future DeLorean, and just how hot is The Human Torch in the Fantastic Four? (Pretty dang hot.)

The next time readers see an asteroid making a deep impact, characters zipping through interplanetary travel, or an evil plot to harbor a new form of destructive energy, they’ll have a scientific foundation to ask simple, but important, questions. Is this reasonable science, rooted in the principles of physics? Even if embellished for the sake of advancing a story, could it theoretically happen? And for Hollywood writers, how can science advance a plot or help a character solve their connundrum? In our podcast below, Dr. Grazier explains why physics and astronomy were such an important bedrock of the first book – and of science-based entertainment – and previews what other areas of science, technology and medicine future sequels will analyze.

In the long run, Hollyweird Science will serve as far more than just a groundbreaking book, regardless of its rather seamless nexus between fun pop culture break-down and serious scientific didactic tool. It’s a part of a conceptual bridge towards an inevitable intellecutal alignment between Hollywood, science and technology. Over the last 10-15 years, portayal of scientists and ubiquity of science content has increased exponentially on screen – so much so, that what was a fringe niche even 20 years ago is now mainstream and has powerful influence in public perception and support for science. Science and technology will proliferate in importance to society, not just in the form of personal gadgets, but as problem-solving tools for global issues like climate change, water access and advancing health quality. Moreover, at a time when Americans’ grasp of basic science is flimsy, at best, any material that can repurpose the universal love of movies and television to impart knowledge and generate excitement is significant. We are at the precipice of forging a permanent link between Hollywood, science and pop culture. The Hollyweird series is the perfect start.

In an exclusive podcast conversation with ScriptPhD.com, Dr. Grazier discussed the overarching themes and concepts that influenced both “Hollyweird Science” and his ongoing consulting in the entertainment industry. These include:

•How the current Golden Age of sci-fi arose and why there’s more science and technology content in entertainment than ever

•Why scientists and screenwriters are remarkably similar

•Why physics and astronomy are the building blocks of the majority of science fiction

•How the “Hollyweird Science” trilogy can be used as a didactic tool for scientists and entertainment figures

•His favorite moments working both in science and entertainment

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development. Follow us on Twitter and Facebook. Subscribe to our podcast on SoundCloud or iTunes.

The Martian, is a film adaptation of the inventive, groundbreaking hard sci-fi adventure tale. Like Robinson Crusoe on Mars, it’s a triumph of engineering and basic science, a love letter to innovation and the greatest feats humans are capable of through collaboration. Directed by sci-fi legend Ridley Scott, and following in the footsteps of space epics Gravity and Interstellar, The Martian offers a stunning virtual imagination of Mars, glimpses of NASA’s new frontier – astronauts on Mars – and the stakes of a mission that will soon become a reality. Below, ScriptPhD.com reviews The Martian (an Editor’s Selection) and, with the help of a planetary researcher at The California Science Center, we break down some basics about Mars missions and the planetary science depicted in the film (interactive video).

That the film version of The Martian even exists is a testament to the unlikely success story of Andy Weir’s novel. A self-described science geek and gainfully employed computer programmer, he started writing a novel on the side, self-publishing chapter by chapter on an independent website. Word spread naturally, readers flocked, eventually, a completed book found a publisher and inevitably Hollywood came calling. Sounds about as realistic as… an astronaut being abandoned on a planet and having to make his own way back to Earth. But this is the exact fast-paced, thrilling plot behind one of the biggest hard sci-fi adventures of all time. Amidst an unexpected Martian sand storm, the crew of Ares 3 (the third fictionalized manned mission to Mars) becomes separated and erroneously thinks one of their members, Mark Watney, has died. They scramble to evacuate the red planet, leaving him very much alive with minimal food, water and tools to fend for himself and no communication to speak of.

With chemistry, botany, physics, engineering, home garage junk science and some self-deprecating humor, Watney must protect himself in the harsh Martian setting, figure out a way to let NASA know he’s alive, craft an escape plan, all while managing to overcome one after another devastating setback. At its heart, The Martian is a pure self-reliant survival tale, a staple of popular fiction. Despite its space setting and unapologetically elaborate scientific plot, it’s a story about a really smart guy who is – in the words of one of the many 70s disco songs throughout – stayin’ alive.

The movie adaptation remains mostly faithful to the central plot, necessarily trimming a few of Mark Watney’s perilous side adventures and unnecessarily supplanting Weir’s sardonic dialogue and one liners. The film sometimes lacks the ubiquitous sense of immediate urgency and desperation present throughout the book, but it makes up for it with more polished transitions and the ability to “think big” that is unique to cinema and critical to a science fiction. Most importantly, Matt Damon (as Watney) ably juggles vulnerability, scientific confidence and geek-chic sarcasm of an iconic sci-fi character.

One of the strengths of Weir’s book is the reader’s ability to visualize every detail of the Mars landscape and its phenomena through intricate first-person storytelling. The most important transition from such a detailed book to film is translating that visual realm, from the rolling red Martian plains and hills to the contrast of the confined space shuttle his crew is in to the chaotic flurry of NASA and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. The vastness of the Martian terrain, incurring both abject loneliness and giddy awe in Watney (with whom we spend the majority of the film) is brilliantly rendered by Scott’s wide angles and grand, sweeping shots. It renders more power to a scene in which the astronaut, unsure if he’ll make it out alive, asks that his parents be told how happy he still is as a scientist, despite everything. “Tell them I love what I do. It’s important. It’s bigger than me.” In that moment, we truly believe him.

For a narrative in which the main character is forced to “science the s—t” out of his predicament, not knowing that back on Earth NASA is doing the very same, one would expect an endless supply of science and technology magic. In that regard, neither the book nor the movie disappoints. But what is truly surprising is the degree of plausibility and accuracy woven throughout the space survival tale. While all recent space films, including Gravity and Interstellar, have been meticulously well researched and inventive, The Martian compounds imagination with incredible scientific reality. For one thing, much of the technology already used by NASA is incorporated into the story. For another, author Andy Weir and director Ridley Scott reaffirmed how hard they worked to get the science right. “Originally The Martian was a serial that I had posted on my website chapter-by-chapter,” said author Weir. “If there were errors in the physics or chemistry problems or whatever, [my readers] would email me. It was great. I got sort of crowd-sourced fact checking. And while some of the science is still not quite air-tight, not only does The Martian take its science very seriously, it managed to thoroughly impress the toughest customer of all – NASA itself!

(For a full Mars primer and breakdown of the planetary science seen in the film, see ScriptPhD.com’s excusive video below.)

With all of the people furiously working to keep Watney alive – the NASA ground crew, Jet Propulsion Laboratory engineers, the Ares 3 crew, and even Watney himself – the real hero and main star of The Martian is science itself. Science facilitates Watney’s survival of the initial Martian storm, allows him to generate food and water to stay alive, traverse the unforgiving landscape and engineer a series of clever technological adaptations to establish communication and series of hopeful escape plans. Most importantly, it allows for an unlikely international alliance to save Watney. “It just goes to show,” [NASA Director] Teddy [Sander] said. “Love of science is universal across all cultures.” This important line from the book is reiterated in the film.

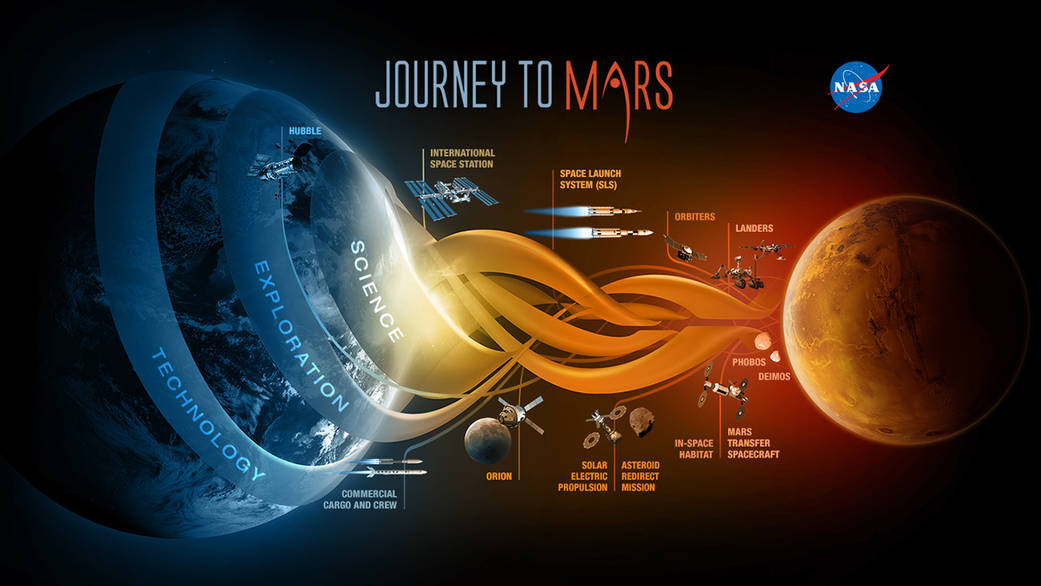

NASA has stated that it aspires to execute a manned mission to Mars by about 2030, a project no doubt buoyed by the exciting revelation that the Curiosity rover has found evidence of flowing water nearby. Expensive, dangerous missions, however, rely on public support for momentum – particularly because NASA research is publicly funded. And movies are often an important cultural gateway to engender and grow such support. NASA advisors of sci-fi film The Europa Report hoped it would inspire a real mission someday. One of ScriptPhD’s favorites from the last few years, Moon, and ambitious sci-fi hit Interstellar have the potential to re-ignite a new space race.

In an exclusive podcast with ScriptPhD.com a few years ago, noted astronomer and science communicator Brian Cox fervently advocated that NASA embrace its greatest challenge to date – manned exploration of Mars: because it’s hard, because we are meant to push the boundaries of the far edges of our galactic frontiers, because space exploration is the greatest universal manifestation of our ability to innovate and engineer. To the extent that The Martian manages to inspire and ignite this idea wih the mainstream public, it will stake claim as more than just a sci-fi benchmark. It will be seen as a catalyst for exploration history. After all, NASA did just announce plans to finally explore life on Jupiter’s moon Europa as depicted in Stanley Kubrik’s classic 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Interested in learning more about all the planetary science that goes into executing a Mars mission? The likelihood of Watney’s survival and some of the technical and scientific feats he pulls off on the red planet? I was privileged to head out to the California Science Center, location of the first ever Viking Mars rover prototype, to break down the science of Mars missions with Devin Waller, a planetary scientist and former Mars researcher.

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development. Follow us on Twitter and Facebook. Subscribe to our podcast on SoundCloud or iTunes.

One of Walt Disney’s enduring lifetime legacies was his commitment to innovation, new ideas and imagination. An inventive visionary, Disney often previewed his inventions at the annual New York World’s Fair and contributed many technological and creative breakthroughs that we enjoy to this day. One of Disney’s biggest fascinations was with space exploration and futurism, often reflected thematically in Disney’s canon of material throughout the years. Just prior to his death in 1966, Disney undertook an ambitious plan to build a utopian “Community of Tomorrow,” complete with state-of-the-art technology. Indeed, every major Disney theme park around the world has some permutation of a themed section called “Tomorrowland,” first introduced at Disneyland in 1955, featuring inspiring Jules Verne glimpses into the future. This ambition is beautifully embodied in Disney Picttures’ latest release of the same name, a film that is at once a celebration of ideas, a call to arms for scientific achievement and good old fashioned idealistic dreaming. The critical relevance to our circumstances today and full ScriptPhD review below.

“This is a story about the future.”

With this opening salvo, we immediately jump back in time to the 1964 World’s Fair in New York City, the embodiment of confidence and scientific achievement at a time when the opportunities of the future seemed limitless. Enthusiastic young inventor Frank Walker (Thomas Robinson), an optimistic dreamer, catches the attention of brilliant scientist David Nix (Hugh Laurie) and his young sidekick Athena, a mysterious little girl with a twinkle in her eye. Through sheer curiosity, Frank follows them and transports himself into a parallel universe, a glimmering, utopian marvel of futuristic industry and technology — a civilization gleaming with possibility and inspiration.

“Walt [Disney] was a futurist. He was very interested in space travel and what cities were going to look like and how transportation was going to work,” said Tomorrowland screenwriter Damon Lindelof (Lost, Prometheus). “Walt’s thinking was that the future is not something that happens to us. It’s something we make happen.”

Unfortunately, as we cut back to present time, the hope and dreams of a better tomorrow haven’t quite worked out as planned. Through the eyes of idealistic Casey Newton (Britt Robertson), thrill seeker and aspiring astronaut, we see a frustrating world mired in wars, environmental devastation and selfish catastrophes. But Casey is smart, stubborn and passionate. She believes the world can be restored to a place of hope and inspiration, particularly through science. When she unexpectedly obtains a mysterious pin — which we first glimpsed at the World’s Fair — it gives her a portal to the very world that young Frank traveled to. Protecting Casey as she delves deeper into the mystery is Athena, who it turns out is a very special time-traveling recruiter. She distributes the pins to a collective of the smartest, most creative people, who gather in the Tomorrowland utopia to work and invent free of the impediments of our current society.

Athena connects Casey with a now-aged Frank (George Clooney), who has turned into a cynical, reclusive iconoclastic inventor (bearing striking verisimilitude to Nikola Tesla). Casey and Frank must partner to return to Tomorrowland, where something has gone terribly awry and imperils the existence of Earth. David Nix, a pragmatic bureaucrat and now self-proclaimed Governor of a more dilapidated Tomorrowland, has successfully harnessed subatomic tachyon particles to see a future in which Earth self-destructs. Unless Casey and Frank, aided by Athena and a little bit of Disney magic, intervene, Nix will ensure the self-fulfilling prophesy comes to fruition.

As the co-protagonist of Tomorrowland Casey Newton symbolizes some of the most important tenets and qualities of a successful scientist. She’s insatiably curious, in absolute awe of what she doesn’t know (at one point looking into space and cooing “What if there’s everything out there?”) and buoyant in her indestructible hope that no challenge can’t be overcome with enough hard work and out-of-the-box originality. She loves math, astronomy and space, the hard sciences that represent the critical, diverse STEM jobs of tomorrow, for which there is still a graduate shortage. That she’s a girl at a time when women (and minorities) are still woefully under-represented in mathematics, engineering and physical science careers is an added and laudable bonus. She defiantly rebels against the layoff of her NASA-engineer father and the unspeakable demolition of the Cape Canaveral platform because “there’s nothing to launch.” The NASA program concomitantly faces the tightest operational budget cuts (particularly for Earth science research) and the most exciting discovery possibilities in its history.

The juxtaposition of Nix and Walker, particularly their philosophical conflict, represents the pedantic drudgery of what much of science has become and the exciting, risky brilliance of what it should be. Nix is pedantic and rigid, unable or unwilling to let go of a traditional credo to embrace risk and, with it, reward. Walker is the young, bushy-tailed, innovative scientist that, given enough rejection and impediments, simply abandons their research and never fulfills their potential. This very phenomenon is occurring amidst an unprecedented global research funding crisis — young researchers are being shut out of global science positions, putting innovation itself at risk. Nix’s prognostication of inevitable self-destruction because we ignore all the warning signs before our eyes, resigning ourselves to a bad future because it doesn’t demand any sacrifice from our present is the weary fatalism of a man that’s given up. His assessment isn’t wrong, he’s just not representative of the kind of scientist that’s going to fix it.

“Something has been lost,” Tomorrowland director Brad Bird believes. “Pessimism has become the only acceptable way to view the future, and I disagree with that. I think there’s something self-fulfilling about it. If that’s what everybody collectively believes, then that’s what will come to be. It engenders passivity: If everybody feels like there’s no point, then they don’t do the myriad of things that could bring us a great future.”

Walt Disney once said, “If you can dream it, you can do it.” Tomorrowland‘s emotional call for dreamers from the diverse corners of the globe is the hope that can never be lost as we navigate a changing, tumultuous world, from dismal climate reports to devastating droughts that threaten food and water supply to perilous conflicts at all corners of our globe. Because ultimately, the precious commodity of innovation and a better tomorrow rests with the potential of this group. We go to the movies to dream about what is possible, to be inspired and entertained. Utilizing the lens of cinematic symbolism, this film begs us to engage our imaginations through science, technology and innovation. It is the epitome of everything Walt Disney stood for and made possible. It’s also a timely, germane message that should resonate to a world that still needs saving.

Oh, and the blink-and-you-miss-it quote posted on the entrance to the fictional Tomorrowland? “Imagination is more important than knowledge.” —Albert Einstein.

View the Tomorrowland trailer:

Tomorrowland goes into wide release on May 22, 2015.

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development. Follow us on Twitter and Facebook. Subscribe to our podcast on SoundCloud or iTunes.

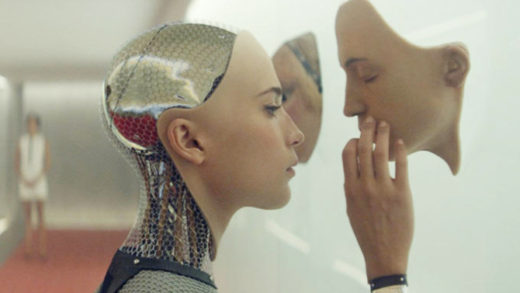

Every so often, a seminal film comes out that ends up being the hallmark of its genre. 2001: A Space Odyssey redefined space and technology in science fiction. Star Wars proved sci-fi could provide blockbuster material, while Blade Runner remains the standard-bearer for post-apocalyptic dystopia. A slate of recent films have broached varying scenarios involving artificial intelligence – from talking robots to sentient computers to re-engineered human capacity. But Ex Machina, the latest film from Alex Garland (writer of the pandemic horror film 28 Days Later and the astro-thriller Sunshine) is the cream of the crop. A stylish, stripped-down, cerebral film, Ex Machina weaves through the psychological implications of an experimental AI robot named Ava possessing preternatural emotional intelligence and free will. It’s a Hitchcockian sci-fi thriller for the geek chic gadget-bearing age, a vulnerable expository inquiry into the isolated meaning of “sentience” (something we will surely contend with in our time) and an honest reproach of technology’s boundless capabilities that somehow manages to celebrate them at the same time.

ScriptPhD.com’s enthusiastic review of this visionary new sci-fi film includes an exclusive Q&A with writer and director Alex Garland from a recent Los Angeles screening.

The preoccupation with superior artificial intelligence as a thematic idea is not a recent phenomenon. After all, Frankenstein is one of the pillars of science fiction – an ode to hypothetical human engineering gone awry. Terminator and its many offshoots gave rise to robotics engineering, whether as saviors or disruptors of humanity. But over the last 16 months, a proliferation of films centered around the incorporation of artificial intelligence in the ongoing microevolution of humanity has signaled a mainstream arrival into the zeitgeist consciousness. 2014 was highlighted with stylish and ambitious but ultimately overmatched digital reincarnation film Transcendence to the understated yet brilliant digital love story Her to the surprisingly smart Disney film Big Hero 6. This year amplifies that trend, with Avengers: Age of Ultron and Chappie marching out robots Elon Musk could only dream about among many other later releases. Wedged in-between is Ex Machina, taking its title from the Latin Deus Ex Machina (God from the machine), a film that prefers to focus on the bioethics and philosophy of scientific limits rather than the razzle-dazzle technology itself. There is still a tendency for sci-fi films concerning AI to engross themselves in presenting over-the-top science, with ensuing wholesale consequences based on theoretical technology, which ultimately hinders storytelling. Ex Machina is a simple story about two male humans, a very advanced-intelligence generated AI robot named Ava, confined in a remote space together, and the life-changing consequences that their interactions engender as a parable for the meaning of humanity. It will be looked back on as one of the hallmark films about AI.

When computer programmer Caleb Smith (Domhall Gleeson) wins an exclusive private week with his search engine company’s CEO Nathan Bateman (Oscar Isaac) it seems like a dream come true. He is helicoptered to the middle of a verdant paradise, where Nathan lives as a recluse in a locked-down, self-sufficient compound. Only Nathan plans to let Caleb be the first to perform a Turing Test on an advanced humanistic robot named Ava (Alicia Vikander). (Incidentally, the technology of creating a completely new robot for cinema was a remarkable process, as the filmmakers discussed in-depth in the New York Times.) The opportunity sounds like a geek’s dream come true, only as the layers slowly peel back, it is apparent that Caleb’s presence is no accident; indeed, the methodology for how Nathan chose him is directly related to the engineering of Ava. Nathan is, depending on your viewpoint, at best a lonely eccentric and at worst an alcoholic lunatic.

For two thirds of the movie, tension is primarily ratcheted through Caleb’s increasingly tense interviews with Ava. She’s smart, witty, curious and clearly has a crush on him. Is something like Ava even possible? Depending on who you ask, maybe not or maybe it already happened. But no matter. The latter third of the movie provides one breathtaking twist after another. Who is testing and manipulating whom? Who is really the “intelligent being” of the three? Are we right to be cautionary and fear AI, even stop it in its tracks before it happens? With seemingly anodyne versions of “helpful robots” already in existence, and social media looking into implementing AI to track our every move, it may be a matter of when, not if.

The brilliance of Alex Garland’s sci-fi writing is his understanding that understated simplicity drives (and even heightens) dramatic tension. Too many AI and techno-futuristic films collapse under the crushing weight of over-imagined technological aspirations, which leave little room for exploring the ramifications thereof. We start Ex Machina with the simple premise that a sentient, advanced, highly programmed robot has been made. She’s here. The rest of the film deftly explores the introspective “what now?” scenarios that will grapple scientists and bio-ethicists should this technology come to pass. What is sentience and can a machine even possess self-awareness? Is their desire to be free of the grasp of their creators wrong and should we allow it? Most importantly, is disruptive AI already here in the amorphous form of social media, search history and private data collected by big technology companies?

The vast majority of Ex Machina consists of the triumvirate of Nathan, Caleb and Ava, toggling between scenes with Nathan and Caleb and Caleb interviewing (experimenting on?) Ava between a glass facade. The progression of intensity in the numbered interviews that comprise the Turing Test are probably the most compelling of the whole film, and nicely set-up the shocking conclusion. In its themes of the human/AI dichotomy and dialogue-heavy tone, Ex Machina compares a lot to last year’s brilliant sci-fi film Her, which rightfully won Spike Jonze the Oscar for Best Original Screenplay. In the former, a lonely professional letter writer becomes attached to and eventually falls in love with his computer operating system Samantha. Eventually, we see the limitations of a relationship void of human contact and the peculiar idiosyncrasies that make us so distinct, the very elusive elements that Samantha seeks to know and understand. (Think this scenario is far off? Many tech developers feel it is not only inevitable but not too far away.To that degree, both of these films show two kinds of sentient future technology chasing after human-ness, yearning for it, yet caution against a bleak future where they supplant it. But whereas Her does so in a sweetly melancholy sentimental fashion, Ex Machina plants a much darker, psychologically prohibitive conclusion.

It turns out that the most terrifying scenario isn’t a world in which artificial intelligence disrupts our lives through a drastic shift in technology. It’s a world in which technology seamlessly integrates itself into the lives we already know.

View the official Ex Machina trailer here:

Alex Garland, writer and director of Ex Machina, stayed after a recent Los Angeles press screening to give an insightful, profound question and answer session about the artificial intelligence as portrayed in the film and its relationship to the recent slew of works depicting interactive technology.

Ava [the robot created by Nathan Bateman] knew what a “good person” was. Why wasn’t she programmed by Nathan to just obey the commandments and not commit certain terrible acts that she does in the film?

AG: The same reason that we aren’t programmed that way. We are asked not to [sin] by social conventions, but no one instructs or programs us not to do it. And yet, a lot of us do bad things. Also, I think what you’re asking is – is Ava bad? Has she done something wrong? And I think that depends on how you choose to look at the movie. I’ve been doing stories for a while, and you hand the story over and you’ve got your intentions but I’ve been doing it for long enough to know that people bring their own [bias] into it.

The way I saw this movie was it was all about this robot – the secret protagonist of the movie. It’s not about these two guys. That’s a trick; an expectation based on the way it’s set up. And if you see the story from her point of view, if her is the right word, she’s in a prison, and there’s the jailer and the jailer’s friend and what she wants to do is get out. And I think if you look at it from that perspective what she does isn’t bad, it’s practical. Yes, she tricks them, but that’s okay. They shouldn’t have been dumb. If you arrive in life in this place, and desire to get out, I think her actions are quite legitimate.

So, that’s a very human-like quality. So let’s say that you’re confronted with a life or death situation with artificial intelligence. Do you have any tricks that you would use [to survive]?

AG: If I’m hypothetically attacked by an AI, I don’t know… run. I think the real question is whether AI is scary. Should we fear them? There’s a lot of people who say we should. Some smarter people than me such as Elon Musk, Stephen Dawkins, and I understand that. This film draws parallels with nuclear power and [Oppenheimer’s caution]. There’s a latent danger there in both. Yet, again, I think it depends on how you frame it. One version of this story is Frankenstein, and that story is a cautionary tale – a religious one at that. It’s saying “Man, don’t mess with God’s creationary work. It’s the wrong thing to do.”

And I framed this differently in my mind. It’s an act of parenthood. We create new conciousnesses on this planet all the time – everyone in this room, everyone on the planet is a product of other people having created this consciousness. If you see it that way, then the AI is the extension of us, not separate from us. A product of us, of something we’ve chosen to do. What would you expect or want of your child? At the bare minimum, you’d want for them to outlive you. The next expectation is that their life is at least as good as yours and hopefully better. All of these things are a matter of perspective. I’m not anti-AI. I think they’re going to be more reasonable than us, potentially in some key respects. We do a lot of unreasonable stuff and they may be fairer.

On the subject of reproduction, in this film, Ava was anatomically correct. Had it been a male, would he have been likewise built correctly?

AG: If you made the male AI in accordance with the experiment that this guy is trying to conduct, then yes. This film is an “ideas movie.” Sometimes it’s asking a question and then presenting an answer, like “Does she have empathy?” or “Is she sentient?”. Sometimes, there isn’t an answer to the question, either because I don’t know the answer or because no one does. The question you’re framing is not “Can you [have sex] with these AI?” it’s “Where does the gender reside?” Where does gender exist in all of us. Is it in the mind, or in the body? It would be easy to construct an argument that Ava has no gender and it would seem reasonable in many respects. You could take her mind and put it in a male body and say “Well, nothing is substantially changed. This is a cosmetic difference between the two.” And yet, then you start to think about how you talk about her and how you perceive her. And to say “he” of Ava just seems wrong. And to say “it” seems weirdly disrespectful. And you end up having this genderless thing coming back to she.

In addition, if you’re going to say gender is in the mind, then demonstrate it. That’s the question I’m trying to provoke. When they have that conversation halfway through the film, these implicit questions, if gender is in the mind, then what is it? Does a man think differently from a woman? Is that really true? Think of something that a man would always think, and you’ll find a man that doesn’t always think that, and you’ll find a woman that does. These are the implicit questions in the film. They don’t all have answers. The key thing about the gender thing isn’t about who is having sex with whom. It’s that this young man is tasked with thinking about what’s going on inside of this machine’s head. That’s his job is to figure that out. And at a certain point he stops thinking about her and he gets it wrong. That’s the issue – why does he stop thinking about it? If the plot shifts in this worked on the audience or any of you in the same way as they worked on the young man, why was that?

Was one of your implicit messages in the film for people to be more conscientious about what they’re sharing on the internet, whether in their searches or social media, and thereby identifying their interests “out there” and how that might be potentially used?

AG: Yes, absolutely. It’s a strange thing, what zeitgeist is. Movies take ages [to make] sometimes – like two and a half years at least. I first wrote this script about four years ago. And then, I find out as we go through production that we’re actually late to the party. There are a whole bunch of films about AI – Transcendance, Automator, Big Hero 6, Age of Ultron [coming out next month], Chappie. Why is that? There hasn’t been any breakthrough in AI, so why are all these people doing this at the same time? And I think it’s not AIs, I think it’s search engines. I think it’s because we’ve got laptops and phones and we, those of us outside of tech, don’t really understand how they work. But we have a strong sense that “they” understand how “we” work. They anticipate stuff about us, they target us with advertising, and I think that makes us uneasy. And I think that these AI stories that are around are symptomatic of that.

That bit in the film about [the dangers of internet identity], in a way it obliquely relates to Edward Snowden, and drawing attention to what the government is doing. But if people get sufficiently angry, they can vote out the government. That is within the power of an electorate. Theoretically, in capitalist terms, consumers have that power over tech companies, but we don’t really. Because that means not having a mobile phone, not having a tablet, a computer, a credit card, a television, and so on. There is something in me that is worried about that. I actually like the tech companies, because I think they’re kind of like NASA in the 1960s. They’re the people going to the moon. That’s great – we wanted to go to the moon. But I’m also scared of them, because they’ve got so much power and we tend not to cope well with a lot of power. So yes, that’s all in the film.

You mentioned Elon Musk earlier, who looks a little bit like [Google co-founder] Sergei Brin. Which tech executive would you say CEO Nathan Batemn is most modeled after?

AG: He wasn’t exactly modeled after an exec. He was modeled more like the companies in some respect. All that “dude, bro” stuff. I sometimes feel that’s what they’re doing. Not to generalize, but it’s a little bit like that – we’re all buddies, come on, dude. While it’s rifling through my wallet and my address book. It’s misleading, a mixed message. I don’t want to sound paranoid about tech companies. I do really like them, I think they’re great. But I think it’s correct to be ambivalent about them. Because anything which is that powerful and that unmarshalled you have to be suspicious of, not even for what we know they’re doing but for what they might do. So, Nathan is more [representative of] a vibe than a person.

For someone equally as scared of AI as Alex is of tech companies, what is the gap between human intelligence and AI intelligence that exists today? How long before we have AI as part of our daily lives?

AG: One of the great pleasures of working on this film was contacting and discussing with people who are at the edge of AI research. I don’t think we’re very close at all. It depends on what you’re talking about. General AI, yes, we’re getting closer. Sentient machines, it’s not even in the ballpark. It’s similar in my mind to a cure for cancer. You can make progress and move forward, but sometimes by going forward it highlights that the goal has receded by complexity. I know Ray Kurtzweil makes some sort of quantified predictions – in 20 years, we’ll be there. I don’t know how you can do that. He’s a smart guy, maybe he’s right. As far as I can tell, in talking to the people who are as close to knowing [about the subject] as I can encounter, it’s something that may or may not happen. And it will probably take a while.

One of the things that’s always bothered me about the Turing Test is that it’s not seeking to know whether or not the thing you’re dealing with is an artificial intelligence. It’s – can you tell that it is? And that’s always bothered me as a kind of weird test. You have a 20,000 question survey, and in the end this one decision comes from a binary point of view. It seems almost flawed.

AG: Yes, you’re completely right. Apart from the fact that it was configured quite a long time ago, it’s primarily a test to see if you can pass the Turing Test. It doesn’t carry information about sentience or potential intelligence. And you could certainly game it. But, it’s also incredibly difficult to pass. So in that respect it’s a really good test. It’s just not a test of what it’s perceived to be a test of, typically. This [experiment in the movie] was supposed to be like a post-Turing Turing Test. The guy says she passed with blind controls, he’s not interested in whether she’ll pass. He’s not interested in her language capacity, which is comparable to a chess computer that wants to win at chess, but doesn’t even know whether it’s playing chess or that it’s a computer. This is the thing you’d do after you pass the Turing Test. But I totally agree with everything you said.

In your research, is there a test that’s been developed that is the reverse of the Turing Test, that seeks to answer whether, in the face of so much technology development, we’ve lost some of our innate human-ness? Or that we’re more machine like?

AG: I think we are machine-like. As far as I know, no test exists like that. The argument at the heart of these things is: is there a significant difference between what a machine can do and what we are? I think how I see this is that we sometimes dignify our conciousness. We make it slightly metaphysical and we deify it because it’s so mysterious to us. An we think, are computers ever going to get up to the lofty heights where we exist in our conciousness? And I suspect that we should be repositioning it here, and we overstate us, in some respects. That’s probably the opposite of what you want to hear.

Do you think that some machine-like quality predates the technology?

AG: I do, yes. I suspect all our human aspects are through evolution, that’s how I think we got here. I can see how conciousness arises from needing to interact in a meaningful and helpful way with other sentient things. Our language develops, and as these things get more sophisticated, conciousness becomes more useful and things that have higher conciousness succeed better. Also, I heard someone talk about conciousness the other day and they were saying “One day, it’s possible that elephants will become sentient.” And that’s a really good example of how we misunderstand sentience. Elephants are already sentient. If you put a dog in front of a mirror, it recognizes its own reflection. It’s self-aware. It knows it’s not looking at another dog. So I put us on that spectrum.

Pertaining to that question, there’s a [critical] moment in the movie where Caleb cuts himself in front of a mirror to make sure that he’s bleeding. And I was going to ask if that’s symbolic of that evolution where conciousness can be undifferentiated between a human and a machine? I was wondering if that scene is a subtle hint that you don’t really know whether you’re the one that is being tested or you’re the tester?

AG: There’s two parts [to that scene]. One is film audiences are literate. I kind of assume that everyone who’s seen that has seen Blade Runner. So they’re going to be imagining to themselves, it’s not her [that is the AI] it’s him. He’s the robot. Here’s the thing. If someone asks of you, here’s a machine, test that machine’s conciousness, tell me if it’s concious or not, it turns out to be a very difficult thing to do. Because [the machine] could act convincingly that it’s concious, but that wouldn’t tell you that it is. Now, once you know that, that actually becomes true of us. You don’t know I’m concious. You think I’m probably concious, you’re not really questioning it. But you believe you are concious, and because I’m like you, I’m another human, you assume I’ve got it. But I’m doing anything that empirically demonstrates that I am concious. It’s an act of faith. And once you know that, you’ve figured that out about the machine and now you can figure it out about the other person. Weirdly, then you can ask it of yourself. That’s where the diminished sense of conciousness comes into it. The things that I believe are special about me are the things I’m feeling – love, fear. And then you think about electrochemicals floods in your brain and the things we’ve been taught and the things we’ve been born with and our behavior patterns and suddenly it gets more and more diminished. To the point that you can think something along the lines of “Am I like a complicated plant that thinks it’s a human?” It’s not such an unreasonable question. So cut your arm and have a look!

In thinking about being a complicated plant, that sounds very isolating. Nathan was really isolated in the movie as well. Do you think that this is indicative of where we’re going with our devices and internet and social media being our social outlet rather than actually socializing? Is AI taking us down that path of isolation?

AG: It may or may not. That could be the case. I’m not on Twitter, I’ve never been on Facebook, I’m not really too [fond of] that stuff. From the outside looking in, it looks like that’s the way people communicate – maybe in a limited way, but in a way I don’t really know. The thing about Nathan is we’re social animals, and our behavior is incredibly modified by people around us. And when we’re removed from modification, our behavior gets very eccentric very fast. I think of it like a kid holding on to a balloon and then they let it go and in a flash it’s gone. I know this because my job is I’m a writer and if I’m on a roll, I can spend six days where I don’t leave the house, I barely see my kids in the corridor, but I’m mainly interested in the fridge and the computer. And I get weird, fast. It’s amazing how quickly it happens. I think anyone who’s read Heart of Darkness or seen the adaptation Apocalypse Now, [Nathan] is like this character Kurtz. He spends too much time upriver, too much time unmodified by the influences that social interactions provide.

Ex Machina goes into wide release in theaters on April 10, 2015.

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development. Follow us on Twitter and Facebook. Subscribe to our podcast on SoundCloud or iTunes.

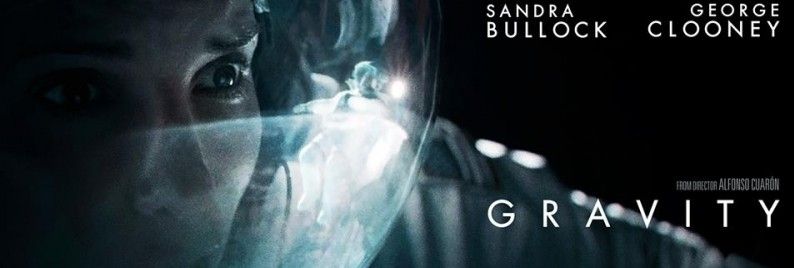

Space movies are almost always grandiose in their storytelling aspirations. The enormity of space, the raw power of the shuttle, the existential quandary of whether we are alone in a vast Universe, and (as is the case in Gravity) an almost-inevitable crisis that must be resolved to steer the astronauts onboard to safety. There is one critical detail, however, that most fail to convey visually—solitude. Dr. Katherine Coleman, who spent thousands of hours aboard the shuttles Columbia and the International Space Station, and who was a primary mentor to star Sandra Bullock, recounts isolation—spatial separation, physical movements, zero gravity and a distant Earth—as the biggest challenge and reward she faced as an astronaut. With a tense, highly focused storyline centered almost entirely on one brave scientist, Gravity is a virtual space flight for the audience, but also a gripping examination of emotional and physical sequestration. Through this vista, we are able to perceive how beautiful, terrifying and enormous space truly is. Full ScriptPhD.com Gravity review under the “continue reading” cut.

It is in this backdrop that we are first introduced to Mission Specialist Ryan Stone (Bullock), a medical engineer turned novice astronaut sent to repair an arm of the Hubble Telescope, and ebullient, assertive veteran Mission Commander Matt Kowalski (Clooney), out on his last voyage in space. During a routine scanning system installation on the exterior of their shuttle, an intentional demolition of an obsolete satellite sends shrapnel debris unexpectedly hurling through space right in their direction. This nightmare scenario, called the Ablation Cascade, was first hypothesized back in 1978 by NASA scientist Donald J. Kessler. Once the density of objects flying in low Earth orbit became high enough (everything from space junk to satellites to intergalactic matter), a collision between two of those objects would lead to further collisions with other nearby objects, each creating more dangerous debris hurling through space. With catastrophic damage to their shuttle, Kowalski and Ryan are the sole survivors with no access to NASA Mission Control and no ability to steer their shuttle home. Limited oxygen supply and a series of tragic consequences soon leave the two astronauts to survival instincts and a last-ditch escape via an international space station as their only hope for returning to Earth.

Much like its smart 2013 predecessor, Europa Report, Gravity is a highly technical, pinpoint-accurate movie that relied on input from NASA astronauts and physicists for every level of execution. Director Alfonso Cuarón, working on his first big screen film in seven years, worked painstakingly alongside a talented crew to implement previously-unproven digital technologies aimed at transporting audiences into weightless space.

Dr. Michael Massimino, a Hubble service specialist with missions on Space Shuttles Columbia and Atlantis, provided insight into space travel and space walking. In addition, Clooney and Bullock spent hours training for zero gravity conditions, while artistic directors and technical crew built special stage-size light boxes and green screens to be able to create remarkable CGI renderings of space from all angles. “Even if [Gravity] was a work of fiction,” Cuarón remarked at a recent screening preview, “We wanted everything, especially the physics of space, to be as accurate as possible.”

Despite the thrilling story and technical fidelity, there is a stylistic beauty to Gravity rooted in simplicity, a silent abyss in the midst of intergalactic chaos. Cuarón’s desire to showcase space as a central physical and thematic piece of his movie is reflected in every frame. He perceived Gravity to be an existential film about “a woman drifting into the void and confronting adversity.” Rather than being tethered to the constraints of a time and place, however, the solar elements of space are the surge of life that inspires her to keep going.

“I used to think that astronauts wanted to go into space for the thrill and adventure,” Bullock reflected. “When I spoke to them, though, I was so moved by their deep love of that world and the beauty of Earth from their perspective. It’s amazing to realize how small we are in this massive universe.” These are the very details that are magnified on screen as the story unfolds – a tiny human being drifting in the enormity of space, a comforting human voice on the radio amid total abyss, a teardrop defying gravity, the magic of another sunrise viewed from millions of miles away.

Far more than just a creative interpretation of space, Gravity is that rare piece of art that can inspire and entertain, a true game-changer in a crowded space film genre. As Dr. Massimino emotionally reminded the press during the preview screening, centers like NASA and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, CA are still doing important research as part of a space program that is very much thriving and as critical as it has ever been. Gravity is a magical way to bring the masses into space and inspire a new generation of support for NASA. “This movie will make folks understand what we do and why it is so important,” Massimino hopes.

As a love letter to space exploration and the sheer strength of human tenacity, Gravity exceeds all expectations.

Gravity goes into wide release in theaters and IMAX on October 4, 2013.

View an extended Gravity trailer:

~*ScriptPhD*~

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire us for creative content development.

Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

]]>

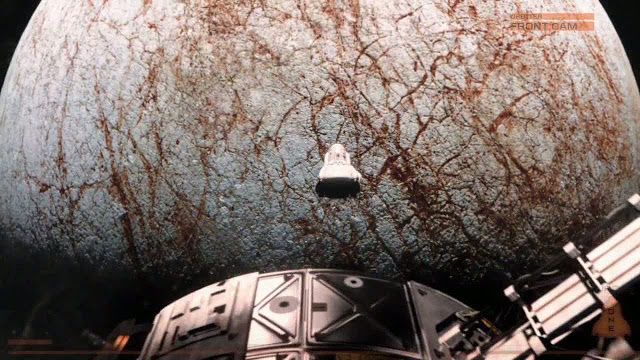

In 2007, new NASA research suggested that underneath the vast ice sheaths of Jupiter’s moon Europa lay oceanic water, which is a key element to support life. The Galileo probe, which had been orbiting the moons of Jupiter since December of 1995, was constantly orbiting and swooshing near the sixth largest moon in the solar system, collecting pictures and data that could prove the existence of liquid water. Then in 2011, scientists hit a proverbial jackpot—evidence for two liquid lakes the volume of the North American Great Lakes underneath a region of jumbled ice blocks termed the ‘Conamara Chaos.’ Even in the wake of such exciting discoveries, critical budget cuts severely threatened NASA’s space program, including the Mars rover and Cassini spacecraft orbiting Saturn. This same time frame gave concurrent rise to private space travel, led by the commercial venture Virgin Galactic and ambitious research company Space X. The merger of limitless industry resources with the possibility of uncovering alien life seems like a perfect Hollywood pitch. Such is the scenario explored in the brilliant documentary-style sci-fi thriller Europa Report. A full ScriptPhD review under the “continue reading” cut.

First conceptualized in 2009, prior to NASA’s landmark discovery of Jupiter’s large lakes, Europa Report explores the fundamental question driving space discovery: “Are we alone?” With private funds and advanced technology at their disposal, the fictitious Europa Ventures space exploration company enlists seven brilliant voyagers for the groundbreaking “Europa Mission,” the first venture beyond Earth’s orbit since 1972. Masterminded by company founders Drs. Samantha Unger and Tarik Pamuk, who also narrate the film and drive the story forward in current time, the multi-year investigative mission (16 months on Europa alone!) would combine state-of-the-art science with modern entertainment. Europa Report’s first act parlays the mundane lull of life in space—exercise to stave off atrophy, recycling urine for distilled water, ship engineers Andrei Blok and James Corrigan bickering in close quarters—overshadowed by the hints of future tragedy.

Indeed, approximately six months into their journey, the Europa Mission communications with ground control are cut off by an unexpected solar storm. From here, the film cleverly seesaws between the present and chronological flashbacks, as the crew bravely decides to press on with their journey. The film’s tempo subtlely, but effectively, picks up with a series of tragic events that affect the crew. When the ship is stranded on the moon’s surface due to heat beneath the ice surface, the crew take drastic steps, led by pilot Rosa Dasque to ensure that the precious data they collected is not for naught.

Europa Report is easily the most realistic depiction of travel and life in space since 2009’s Moon and the 1960s standard-bearer 2001: A Space Odyssey. Committed to the accuracy of its sets, shuttle, space imagery and scientific data, Europa Report relied on heavy consultation with NASA/Jet Propulsion Laboratory, SpaceX and other scientific leaders from the planning and execution of the mission to what the surface of Europa would look like. Filmmakers worked with astrobiologists to conceive theoretical, yet plausible, Europa life forms from the bioluminescent ones that exist deep in the Earth’s oceans. The depiction of the Europa landing is one of the most exciting science movie moments I have ever seen on screen.

With the help of NASA and SpaceX, set designer Eugenio Caballero built a fully authentic spaceship, including living quarters, control area and zero gravity wirework. After production was complete, the visual effects team replicated the Europa exterior environment based on data and imagery collected during the Galileo mission. Perhaps as a result, some of the film’s strongest sequences occur when Dr. Katya Petrovna tenuously ventures on the icy surface to collect data and explore the surroundings, leading to the heart-stopping conclusion that both seals the team’s ultimate fate and reaffirms the value of their mission.

“This project felt like a unique opportunity to do something plausible but forward thinking, somewhere between NASA and Star Trek,” said Ben Browning, whose company Wayfare Entertainment developed the film.

Europa Report is constructed to feel like a documentary or voyeuristic web stream of a very real (and altogether possible) scientific experiment. That a reality show would be borne of such an undertaking is a foregone conclusion. Nevertheless, the film leaves several important overarching existential questions that we must examine in our inevitable quest to search the galaxy for extra-terrestrial life. Even if we find life forms in the outer galaxy, do we really want to know what’s out there? Or perturb it? In the case of Europa Report, a terrifying conclusion conjures up as many fears as it answers exciting possibilities. Secondly, as technology makes extreme space travel to previously-unreached distances possible, we must never forget the element of danger that fuels the bravery of the astronauts and scientist that

undertake these endeavors. Lastly, is the commercialization of space a good idea? In the wake of celebrities buying shuttle rides into Earth’s orbit and space ventures funded by billionaires, who will maintain regulatory oversight and scientific integrity?

Ultimately, it’s inevitable that there will be a real-life mission to Europa, or even beyond. And an even bigger possibility that a groundbreaking discovery of current life in outer space will be made. But until that day, Europa Report unveils a grand science experiment before our eyes and perhaps, even a glimpse into the future.

View a trailer for Europa Report:

Europa Report goes into limited theatrical release on August 2, 2013 and is available On Demand.

~*ScriptPhD*~

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development.

Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

]]>

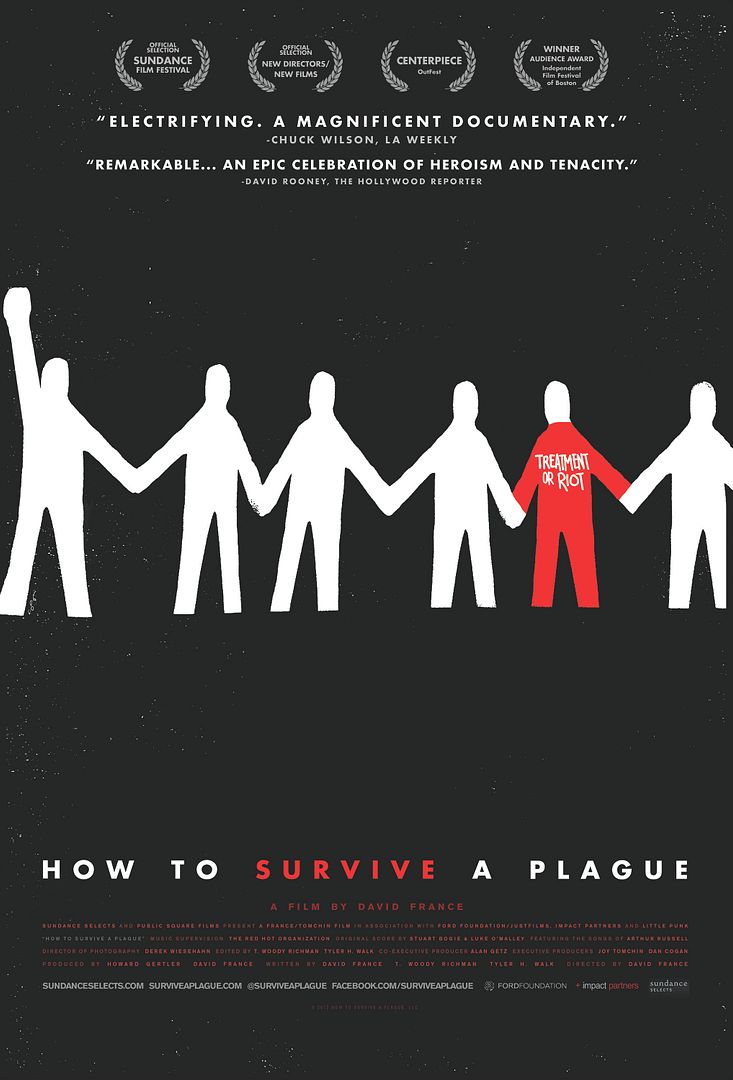

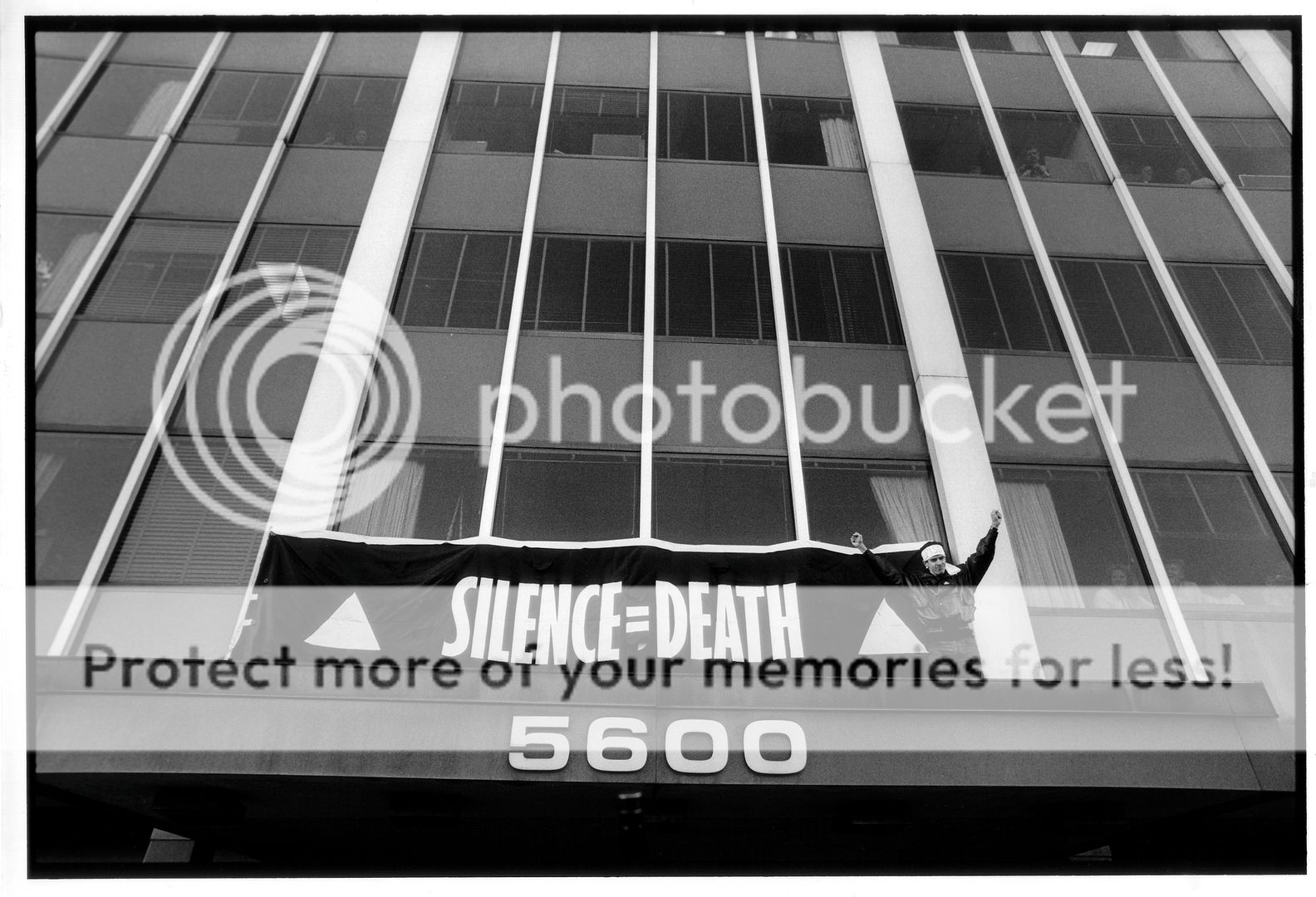

The history of science movies nominated for Oscars is not a very long one. Aside from the technical achievement awards or an occasional nomination for acting merits, the Best Picture category has historically not opened its doors to scientific content, save for notable nominees “A Clockwork Orange,” “District 9,” “Inception” and “Avatar.” A documentary about science has never been nominated for the Best Documentary category, until this year, with How To Survive a Plague, Director David France’s stunning account of the brave activists that brought the AIDS epidemic to the attention of the government and science community in the disease’s darkest early days. “Plague” set history last weekend by becoming the first “Best Documentary” nominee with an almost entirely scientific/biomedical narrative. More importantly, it also established a standard by which future science documentaries should use emotional storytelling to captivate audiences and inspire action. ScriptPhD review and discussion under the “continue reading” cut.