The Martian, is a film adaptation of the inventive, groundbreaking hard sci-fi adventure tale. Like Robinson Crusoe on Mars, it’s a triumph of engineering and basic science, a love letter to innovation and the greatest feats humans are capable of through collaboration. Directed by sci-fi legend Ridley Scott, and following in the footsteps of space epics Gravity and Interstellar, The Martian offers a stunning virtual imagination of Mars, glimpses of NASA’s new frontier – astronauts on Mars – and the stakes of a mission that will soon become a reality. Below, ScriptPhD.com reviews The Martian (an Editor’s Selection) and, with the help of a planetary researcher at The California Science Center, we break down some basics about Mars missions and the planetary science depicted in the film (interactive video).

That the film version of The Martian even exists is a testament to the unlikely success story of Andy Weir’s novel. A self-described science geek and gainfully employed computer programmer, he started writing a novel on the side, self-publishing chapter by chapter on an independent website. Word spread naturally, readers flocked, eventually, a completed book found a publisher and inevitably Hollywood came calling. Sounds about as realistic as… an astronaut being abandoned on a planet and having to make his own way back to Earth. But this is the exact fast-paced, thrilling plot behind one of the biggest hard sci-fi adventures of all time. Amidst an unexpected Martian sand storm, the crew of Ares 3 (the third fictionalized manned mission to Mars) becomes separated and erroneously thinks one of their members, Mark Watney, has died. They scramble to evacuate the red planet, leaving him very much alive with minimal food, water and tools to fend for himself and no communication to speak of.

With chemistry, botany, physics, engineering, home garage junk science and some self-deprecating humor, Watney must protect himself in the harsh Martian setting, figure out a way to let NASA know he’s alive, craft an escape plan, all while managing to overcome one after another devastating setback. At its heart, The Martian is a pure self-reliant survival tale, a staple of popular fiction. Despite its space setting and unapologetically elaborate scientific plot, it’s a story about a really smart guy who is – in the words of one of the many 70s disco songs throughout – stayin’ alive.

The movie adaptation remains mostly faithful to the central plot, necessarily trimming a few of Mark Watney’s perilous side adventures and unnecessarily supplanting Weir’s sardonic dialogue and one liners. The film sometimes lacks the ubiquitous sense of immediate urgency and desperation present throughout the book, but it makes up for it with more polished transitions and the ability to “think big” that is unique to cinema and critical to a science fiction. Most importantly, Matt Damon (as Watney) ably juggles vulnerability, scientific confidence and geek-chic sarcasm of an iconic sci-fi character.

One of the strengths of Weir’s book is the reader’s ability to visualize every detail of the Mars landscape and its phenomena through intricate first-person storytelling. The most important transition from such a detailed book to film is translating that visual realm, from the rolling red Martian plains and hills to the contrast of the confined space shuttle his crew is in to the chaotic flurry of NASA and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. The vastness of the Martian terrain, incurring both abject loneliness and giddy awe in Watney (with whom we spend the majority of the film) is brilliantly rendered by Scott’s wide angles and grand, sweeping shots. It renders more power to a scene in which the astronaut, unsure if he’ll make it out alive, asks that his parents be told how happy he still is as a scientist, despite everything. “Tell them I love what I do. It’s important. It’s bigger than me.” In that moment, we truly believe him.

For a narrative in which the main character is forced to “science the s—t” out of his predicament, not knowing that back on Earth NASA is doing the very same, one would expect an endless supply of science and technology magic. In that regard, neither the book nor the movie disappoints. But what is truly surprising is the degree of plausibility and accuracy woven throughout the space survival tale. While all recent space films, including Gravity and Interstellar, have been meticulously well researched and inventive, The Martian compounds imagination with incredible scientific reality. For one thing, much of the technology already used by NASA is incorporated into the story. For another, author Andy Weir and director Ridley Scott reaffirmed how hard they worked to get the science right. “Originally The Martian was a serial that I had posted on my website chapter-by-chapter,” said author Weir. “If there were errors in the physics or chemistry problems or whatever, [my readers] would email me. It was great. I got sort of crowd-sourced fact checking. And while some of the science is still not quite air-tight, not only does The Martian take its science very seriously, it managed to thoroughly impress the toughest customer of all – NASA itself!

(For a full Mars primer and breakdown of the planetary science seen in the film, see ScriptPhD.com’s excusive video below.)

With all of the people furiously working to keep Watney alive – the NASA ground crew, Jet Propulsion Laboratory engineers, the Ares 3 crew, and even Watney himself – the real hero and main star of The Martian is science itself. Science facilitates Watney’s survival of the initial Martian storm, allows him to generate food and water to stay alive, traverse the unforgiving landscape and engineer a series of clever technological adaptations to establish communication and series of hopeful escape plans. Most importantly, it allows for an unlikely international alliance to save Watney. “It just goes to show,” [NASA Director] Teddy [Sander] said. “Love of science is universal across all cultures.” This important line from the book is reiterated in the film.

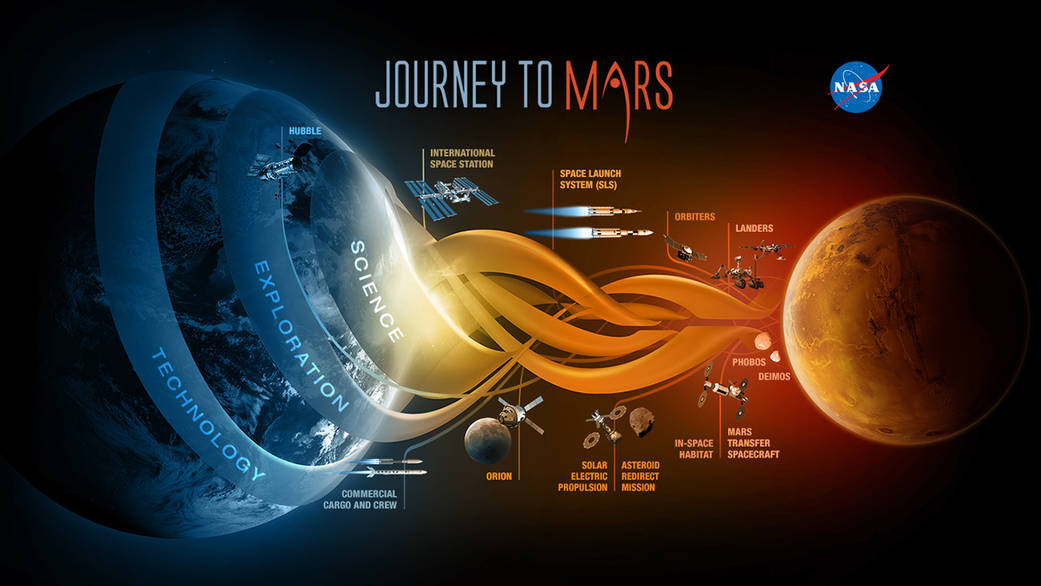

NASA has stated that it aspires to execute a manned mission to Mars by about 2030, a project no doubt buoyed by the exciting revelation that the Curiosity rover has found evidence of flowing water nearby. Expensive, dangerous missions, however, rely on public support for momentum – particularly because NASA research is publicly funded. And movies are often an important cultural gateway to engender and grow such support. NASA advisors of sci-fi film The Europa Report hoped it would inspire a real mission someday. One of ScriptPhD’s favorites from the last few years, Moon, and ambitious sci-fi hit Interstellar have the potential to re-ignite a new space race.

In an exclusive podcast with ScriptPhD.com a few years ago, noted astronomer and science communicator Brian Cox fervently advocated that NASA embrace its greatest challenge to date – manned exploration of Mars: because it’s hard, because we are meant to push the boundaries of the far edges of our galactic frontiers, because space exploration is the greatest universal manifestation of our ability to innovate and engineer. To the extent that The Martian manages to inspire and ignite this idea wih the mainstream public, it will stake claim as more than just a sci-fi benchmark. It will be seen as a catalyst for exploration history. After all, NASA did just announce plans to finally explore life on Jupiter’s moon Europa as depicted in Stanley Kubrik’s classic 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Interested in learning more about all the planetary science that goes into executing a Mars mission? The likelihood of Watney’s survival and some of the technical and scientific feats he pulls off on the red planet? I was privileged to head out to the California Science Center, location of the first ever Viking Mars rover prototype, to break down the science of Mars missions with Devin Waller, a planetary scientist and former Mars researcher.

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development. Follow us on Twitter and Facebook. Subscribe to our podcast on SoundCloud or iTunes.

From a sci-fi and entertainment perspective, 2015 may undoubtedly be nicknamed “The Year of The Robot.” Several cinematic releases have already explored various angles of futuristic artificial intelligence (from the forgettable Chappie to the mainstream blockbuster Marvel’s Avengers: Age of Ultron to the intelligent sleeper indie hit Ex Machina), with several more on the way later this year. Two television series premiering this summer, limited series Humans on AMC and Mr. Robot on USA add thoughtful, layered (and very entertaining) discussions on the ethics and socio-economic impact of the technology affecting the age we live in. While Humans revolves around hyper-evolved robot companions, and Mr. Robot a singular shadowy eponymous cyberhacking organization, both represent enthusiastic Editor’s Selection recommendations from ScriptPhD. Reviews and an exclusive interview with Humans creators/writers Jonathan Brackley and Sam Vincent below.

Never in human history has technology and its potential reached a greater permeation of and importance in our daily lives than at the current moment. Indeed, it might even be changing the way our brains function! With entertainment often acting as a reflection of socially pertinent issues and zeitgeist motifs, it’s only natural to examine the depths to which robots (or any artificial technology) might subsume human life. Will they take over our jobs? Become smarter than us? Nefariously affect human society? These fears about the emotional lines between humans and their technology are at the heart of AMC’s new limited series Humans. It is set in the not-too-distant future, where the must have tech accessory is a ‘synth,’ a highly malleable, impeccably programmed robotic servant capable of providing any services – at the individual, family or macro-corporate level. It’s an idyllic ambition, fully realized. Busy, dysfunctional parents Joe and Laura obtain family android Anita to take care of basic housework and child rearing to free up time. Beat cop Pete’s rehabilitation android is indispensable to his paralyzed wife. And even though he doesn’t want a new synth, scientist George Millikan is thrust with a ‘care unit’ Vera by the Health Service to monitor his recovery from a stroke. They can pick fruit, clean up trash, work mindlessly in factories and sweat shops make meals, even provide service in brothels – an endless range of servile labor that we are uncomfortable or unwilling to do ourselves.

Humans brilliantly weaves the problems of this artificial intelligence narrative into multiple interweaving story lines. Anita may be the perfect house servant to Joe, but her omniscience and omnipresence borders on creepiness to wife Laura (and by proxy, the audience). Is Dr. Millikan (who helped craft the original synth technology) right that you can’t recycle them the way you would an old iPhone model? Or is he naive for loving his synth Odi like a son? And even if you create a Special Technologies Task Force to handle synth-related incidents, guaranteeing no harm to humans and minimal, if any, malfunctions, how can there be no nefarious downside to a piece of technology? They could, in theory, be obtained illegally and reprogrammed for subversive activity. If the original creator of the synths wanted to create a semblance of human life – “They were meant to feel,” he maintains – then are we culpable for their enslaved state? Should we feel relieved to see a synth break out of the brothel she’s forced to work in, or another mysterious group of synths that have somehow become sentient unite clandestinely to dream of a dimension where they’re free?

In reality, we already are in the midst of an age of artificial intelligence – computers. Powerful, fast, already capable of taking over our workforce and reshaping our society, they are the amorphous technological preamble to more specifically tailored robots, incurring all of the same trepidation and uncertainty. Mr. Robot, one of the smartest TV pilots in recent memory, is a cautionary tale about cyberhacking, socioeconomic vulnerability and the sheer reliance our society unknowingly places in computers. Its central themes are physically embodied in the central character of Elliot, a brilliant cybersecurity engineer by day/vigilante cyberhacker by night, battling schizophrenia and extreme social anxiety. To Elliott, the ubiquitous nature of computer power is simultaneously appealing and repulsive. Everything is electronic today – money, corporate transactions, even the way we communicate socially. As a hacker, he manipulates these elements with ease to get close to people and to solve injustice (carrying a Dexter-style digital cemetery of his conquests). But as someone who craves human contact he loathes the way technology has deteriorated human interaction and encouraged nameless, faceless corporate greed.

Elliot works for Allstate Security, whose biggest client is an emblem of corporate evil and economic diffidence. When they are hacked, Elliot discovers that it’s a private digital call to arms by a mysterious underground group called Mr. Robot (resembling the cybervigilante group Anonymous). They’ve hatched a plan to to concoct a wide-scale economic cyber attack that will result in the single biggest redistribution of wealth and debt forgiveness in history, and recruited Elliot into their organization. The question, and intriguing premise of the series, is whether Elliot can juggle his clean-cut day job, subversive underground hacking and protecting society one cyberterrorist act at a time, or if they will collapse under the burden of his conscience and mental illness.

Humans is a purview into the inevitable future, albeit one that may be creeping on us faster than we want it to. Even if hyper-advanced artificial intelligence is not an imminent reality and our fears might be overblown, the impact of technology on economics and human evolution is a reality we will have to grapple with eventually. And one that must inform the bioethics of any advanced sentient computing technology we create and release into the world. Mr. Robot is a stark reminder of our current present, that cyberterrorism is the new normal, that its global impact is immense, and (as with the case of artificial robots), our advancement of and reliance on technology is outpacing humans’ ability to control it.

ScriptPhD.com was extremely fortunate to chat directly with Humans writers Jonathan Brackley and Sam Vincent about the premise and thematic implications of their show. Here’s what they had to say:

ScriptPhD.com: Is “Humans” meant to be a cautionary tale about the dangers of complex artificial intelligence run amok or a hypothetical bioethical exploration of how such technology would permeate and affect human society?

Jonathan and Sam: Both! On one level, the synths are a metaphor for our real technology, and what it’s doing to us, as it becomes ever more human-like and user-friendly – but also more powerful and mysterious. It’s not so much hypothesising as it is extrapolating real world trends. But on a deeper story level, we play with the question – could these machines become more, and if so, what would happen? Though “run amok” has negative connotations – we’re trying to be more balanced. Who says a complex AI given free rein wouldn’t make things better?

SPhD: I found it interesting that there’s a tremendous range of emotions in how the humans related to and felt about their “synths.” George has a familial affection for his, Laura is creeped out/jealous of hers while her husband Joe is largely indifferent, policeman Peter grudgingly finds his synth to be a useful rehabilitation tool for his wife after an accident. Isn’t this reflective of the range of emotions in how humans react to the current technology in our lives, and maybe always will?

J&S: There’s always a wide range of attitudes towards any new technology – some adopt enthusiastically, others are suspicious. But maybe it’s become a more emotive question as we increasingly use our technology to conduct every aspect of our existence, including our emotional lives. Our feelings are already tangled up in our tech, and we can’t see that changing any time soon.

SPhD: Like many recent works exploring Artificial Intelligence, at the root of “Humans” is a sense of fear. Which is greater – the fear of losing our flaws and imperfections (the very things that make us human) or the genuine fear that the sentient “synths” have of us and their enslavement?

J&S: Though we show that synths certainly can’t take their continued existence for granted, there’s as much love as fear in the relationships between our characters. For us, the fear of how our technology is changing us is more powerful – purely because it’s really happening, and has been for a long time. But maybe it’s not to be feared – or not all of it at least…

Catch a trailer and closer series look at the making of Humans here:

And catch the FULL first episode of Mr. Robot here:

Mr. Robot airs on USA Network with full episodes available online.

Humans premieres on June 28, 2015 on AMC Television (USA) and airs on Channel 4 (UK).

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development. Follow us on Twitter and Facebook. Subscribe to our podcast on SoundCloud or iTunes.

On February 28, 1998, the revered British medical journal The Lancet published a brief paper by then-high profile but controversial gastroenterologist Andrew Wakefield that claimed to have linked the MMR (measles, mumps and rubella) vaccine with regressive autism and inflammation of the colon in a small case number of children. A subsequent paper published four years later claimed to have isolated the strain of attenuated measles virus used in the MMR vaccine in the colons of autistic children through a polymerase chain reaction (PCR amplification). The effect on vaccination rates in the UK was immediate, with MMR vaccinations reaching a record low in 2003/2004, and parts of London losing herd immunity with vaccination rates of 62%. 15 American states currently have immunization rates below the recommended 90% threshold. Wakefield was eventually exposed as a scientific fraud and an opportunist trying to cash in on people’s fears with ‘alternative clinics’ and pre-planned a ‘safe’ vaccine of his own before the Lancet paper was ever published. Even the 12 children in his study turned out to have been selectively referred by parents convinced of a link between the MMR vaccine and their children’s autism. The original Lancet paper was retracted and Wakefield was stripped of his medical license. By that point, irreparable damage had been done that may take decades to reverse.

How could a single fraudulent scientific paper, unable to be replicated or validated by the medical community, cause such widespread panic? How could it influence legions of otherwise rational parents to not vaccinate their children against devastating, preventable diseases, at a cost of millions of dollars in treatment and worse yet, unnecessary child fatalities? And why, despite all evidence to the contrary, have people remained adamant in their beliefs that vaccines are responsible for harming otherwise healthy children, whether through autism or other insidious side effects? In his brilliant, timely, meticulously-researched book The Panic Virus, author Seth Mnookin disseminates the aggregate effect of media coverage, echo chamber information exchange, cognitive biases and the desperate anguish of autism parents as fuel for the recent anti-vaccine movement. In doing so, he retraces the triumphs and missteps in the history of vaccines, examines the social impact of rejecting the scientific method in a more broad perspective, and ways that this current utterly preventable public health crisis can be avoided in future scenarios. A review of The Panic Virus, an enthusiastic ScriptPhD.com Editor’s Selection, follows below.

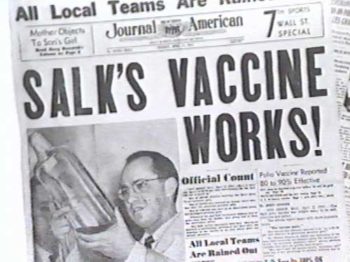

Such fervent controversy over inoculating young children for communicable diseases might have seemed unimaginable to the pre-vaccine generations. It wasn’t long ago, Mnookin chronicles, that death and suffering at the hands of diseases like polio and small pox were the accepted norm. In 18th Century Europe, for example, 400,000 people per year regularly died of small pox, and it caused one third of all cases of blindness. So desperate were people to avoid the illnesses’ ravages, that crude, rudimentary inoculation methods were employed, even at the high risk of death, to achieve life-long immunity. A 1916 polio outbreak in New York City, with fatality rates between 20 and 25 percent, frayed nerves and public health infrastructure to the point of near-anarchy. As the disease waxed and waned in outbreaks throughout the decades that followed, distraught parents had no idea about how to protect their children, who were often far more susceptible to fatality than adults. By the time Jonas Salk’s polio vaccine breakthrough was announced as “safe, effective and potent” on April 12, 1955, pandemonium broke out. “Air raid sirens were set off,” Mnookin writes. “Traffic lights blinked red; churches’ bells rang; grown men and women wept; schoolchildren observed a moment of silence.” Salk’s discovery was hailed as “one of the greatest events in the history of medicine.”

Mnookin doesn’t let scientists off the hook where vaccines are concerned, however, and rightfully so. Starting around World War II, with advances such as the cowpox and polio vaccines, along with the dawning of the Antibiotics Age, eradicating death and suffering from communicable diseases and bacterial infections, a hubris and sense of superiority began to creep into the scientific establishment, with dangerous consequences. Fearing the threat of biological warfare during World War II, a 1941 hastily-constructed US military campaign to vaccinate all US troops against yellow fever resulted in batches contaminated with Hepatitis B, resulting in 300,000 infections and 60 deaths. The first iteration of Salk’s polio vaccine was only 60-90% effective before being perfected and eventually replaced by the more effective Sabin vaccine. Furthermore, dozens of children who had received doses from the first batch of vaccines were paralyzed or killed due to contaminated vaccines that had failed safety tests. In 1976, buoyed by the death of a soldier from a flu virus that bore striking genetic similarity to the 1918 Spanish flu epidemic strain, President Gerald Ford instituted a nation-wide mass vaccination initiative against a “swine flu” epidemic. Unfortunately, although 40 million Americans were vaccinated in three months, 500 developed symptoms of Guillain-Barré syndrome (30 died), seven times higher than would normally be expected as a rare side effect of vaccination. Many people feel that the scars of the 1976 fiasco have incurred a permanent distrust of the medical establishment and have haunted public health influenza immunization efforts to this day.

These black marks on the otherwise miraculous, life-saving history of vaccine development not only instilled a gradual mistrust in public health officials, but laid the groundwork for the incendiary autism-vaccine scandal. The only missing components were a proper context of panic, a snake oil salesman and a compliant media willing to spread his erroneous message.

Enter the autism epidemic and Andrew Wakefield’s hoax. Because this seminal event had such a profound effect on the formation and proliferation of the current anti-vaccine movement, it is chronicled in far greater detail than our introduction above. From precursor incidents that ripened the potential for coercion to the Wakefield’s shoddy methodology and the naive medical community that took him at his word, Mnookin weaves through this case with well-researched scientific facts, interesting interviews and logic. A large chunk of the book is ultimately devoted to the psychology of what the anti-vaccine movement really is: a cognitive bias and a willingness to stay adamant in the belief that vaccines cause harm despite all evidence to the contrary. “If you assume,” he writes, “as I had, that human beings are fundamentally logical creatures, this obsessive preoccupation with a theory that has for all intents and purposes been disproved is hard to fathom. But when it comes to decisions around emotionally charged topics, logic often takes a back seat to a set of unconscious mechanisms that convince us that it is our feelings about a situation and not the facts that represent the truth.”

Given this blog’s objective to cover science and technology in entertainment and media, it would be disingenuous to write about the anti-vaccine movement without recognizing the implicit role played by the media and entertainment industries in exacerbating the polemic. By lending a voice to the anti-vaccine argument, even in a subtle manner or in a journalistic attempt to “be fair to the other side,” over time, an echo chamber of lies turned into an inferno. In 1982, an hour-long NBC documentary called DPT: Vaccine Roulette aired, overemphasizing rare side effects in babies from vaccinations to a nation of alarmed parents and completely undermining their benefits. It was a propaganda piece, but an important hallmark for what would come later. A 2008 episode of the popular ABC hit show Eli Stone irresponsibly aired anti-vaccination propaganda involving a lawyer questioning a pharmaceutical company that manufactures vaccines due to the even then-debunked link to autism. For several recent years, actress and Playboy bunny Jenny McCarthy (who is given an entire chapter by Mnookin) became a tireless advocate against vaccinations, believing that they gave her son autism. She didn’t have any scientific proof for this, but was nevertheless given a platform by everyone from Larry King on CNN to a fawning Oprah Winfrey.

As it turns out, McCarthy’s son never even had autism, but rather a very rare and treatable neurological disorder. In a self-penned editorial for the Chicago Sun-Times, she has officially retroactively denied her anti-vaccine stance, and says she simply wants “more research on their effectiveness.” An extremely sympathetic 2014 eight-page Washington Post magazine article profile of prominent anti-vaccine activist Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. (who believes in the link between vaccines and autism) repeated his talking points numerous times throughout. This, among an endless cycle of interviews and appearances by defiant anti-vaccine proponents, given equal air time side-by-side with frustrated scientists, as if both positions were somehow viable, and worthy of journalistic debate. Once the worm was out of the can, no amount of rational discourse could temper the visceral antipathy that had been created. This is irresponsible, dangerous and flat-out wrong. When the public is confused about an esoteric issue pertaining to science, medicine or technology, influencers in the public eye cannot perpetuate misinformation.

Despite the unanimous medical repudiation of Wakefield’s fraudulent methods and conclusions and the retraction of his Lancet paper, an irreversible and insidious myth had begun permeating, first among the autism community, then spreading to proponents of organic and holistic approaches to health and finally, to mainstream society. In the aftermath of the controversy, epidemiological studies debunking the autism-vaccination “link,” combined with a growing disease crisis, have forced the largest US-based autism advocacy organization to reverse its stance and fully endorse vaccination to a still-divided community. Wakefield remains more defiant than ever, insisting to this day that his research was valid, attempting to sue the British journalism outlet that funded the inquiry into his fraud and peddling holistic treatments for autism as well as his “alternative” vaccine. Sadly, the public health ramifications have nothing short of disastrous, with a dangerous recurrence of several major childhood diseases.

A few examples of the many systemic casualties of the anti-vaccination movement (many occurring just since the publication of Mnookin’s book):

•A summary from the American Medical Association about the nascence of the measles crisis in 2011, when the US saw more measles cases than it had in 15 years

•Immunization rates falling so low that schools in some communities are being forced to terminate personal exemption waivers and, in some cases, legally mandated immunization for public school attendance

•California’s worst whooping cough epidemic in 70 years.

•Most recently, a measles outbreak at Disneyland, resulting in 26 cases spread across four states, after an unvaccinated woman visited the theme park

•Anti-vaccine hysteria has spread to Europe, which has had a measles rise of 348% from 2013 to 2014 (and growing), along with an alarming resurgence of pertussis

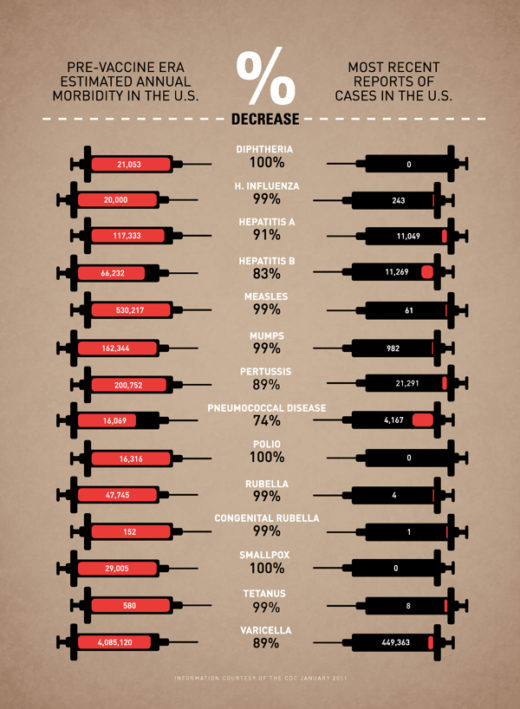

The scientific evidence that vaccines work is indisputable, and as the below infographic summarizes, their impact on morbidity from communicable diseases is miraculous. Sadly, now that the anti-vaccine movement has streamlined into the general population, anxious parents are conflicted as to whether vaccinating is the right choice for their children. We must start by going back to the basics of what a vaccine actually is and how it works. Next, we must reiterate the critical importance that maintaining herd immunity above 92-95% plays in protecting not only those too young or immunocompromised to be vaccinated, but even fully vaccinated populations. If all else fails, try emailing skeptical friends and family a clever graphic cartoon that breaks down digestible vaccine facts. Simply put: getting vaccinated is not a personal choice, it’s a selfish and dangerous choice.

The Panic Virus is first and foremost an incredibly entertaining, well-written narrative of the dawn of an anti-vaccine phenomenon which has reached a critical mass. It is also an important case study and cautionary tale about how we process and disseminate information in the age of the Internet and access to instant information. It is also an indictment on a trigger-happy, ratings-driven, sensationalist media that reports “news” as they interpret it first, and bother to check for facts later. In the case of the anti-vaccine movement of the last few years, the media fueled the fire that Andrew Wakefield started, and once a gaggle of angry, sympathetic parents was released, it was difficult (if-near impossible) to undo the damage. This type of journalism, Mnookin writes, “gives credence to the belief that we can intuit our way through all the various decisions we need to make in our lives and it validates the notion that our feelings are a more reliable barometer of reality than the facts.” Sadly, the autism-vaccine panic movement is not an outlying incident, but rather a disconcerting emblem of a growing anti-science agenda. The UN just released its most dire and alarming report ever issued on man-made climate change impacts, warning that temperature changes and industrial pollution will affect not just the environment, extreme weather events and coastal cities, but even the stability of our global economy itself. Immediate rebuttals from an influential lobbying group tried to undermine the majority of the scientists’ findings. So toxic is the corporate and political resistance to any kind of mitigating action, that some feel we need a technological or political miracle to stave off a certain environmental crisis. At a time when physicists are serious debate on evolution versus creationism and thousands of public schools across the United States use taxpayer funds to teach creationism in the classroom.

Mnookin’s book is an important resource and conversation starter for scientists, researchers and frustrated physicians as they carve out talking points and communication strategies to establish a dialogue with the public at large. When young parents have questions about vaccines (no matter how erroneous or ill-informed), pediatricians should already have materials for engaging in a positive, thoughtful discussion with them. When scientists and researchers encounter anti-science proclivities or subversive efforts to undermine their advocacy for a pressing issue, they should be armed with powerful, articulate communicators — ready and willing to deliberate in the media and convey factual information in an accessible way. When Jenny McCarthy and a gaggle of new-age holistic herbologists were peddling their “mommy instincts” and conspiracy theories against vaccines, far too many scientists and physicians simply thought it was beneath them to even engage in a discussion about something whose certainty and proof of concept was beyond reproach. Now, the newest polling suggests that nothing will change an anti-vaxxer’s mind, not even factual reasoning. Going forward, regardless of the issue at hand, this type of response can never happen again. The cost of complacency or arrogance is nothing short of life or death.

The Panic Virus by Seth Mnookin is currently available on paperback and Kindle wherever books are sold. For further reading on how to deal with the complexities of the anti-vaccine movement aftermath, we suggest the recent book On Immunity: An Inoculation by Northwestern University lecturer Eula Bliss.

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development. Follow us on Twitter and Facebook. Subscribe to our podcast on SoundCloud or iTunes.

As part of an ongoing recommitment to its sci-fi genre roots, SyFy Channel is unveiling the original scripted drama Ascension, for now a six hour mini-series, and possible launch for a future series. It follows a crew aboard the starship Ascension, as part of a 1960s mission that sent 600 men, women and children on a 100 year planned voyage to populate a new world. In the midst of political unrest onboard the vessel, the approach of a critical juncture in the mission and the first-ever murder onboard the craft, the audience soon learns, there is more to the mission than meets the eye. Which can also be said of this multi-layered, ambitious, sophisticated mini-series. Full ScriptPhD review below.

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, largely fueled by the heigh of Cold War tensions with the Soviet Union and fears of mutual nuclear destruction, the United States government, in conjunction with NASA, launched a project that would have sent 150 people into various corners of space — from the Moon, to Mars and eventually Saturn. Code-named Orion, the project officially launched in 1958 at General Atomics in San Diego under the leadership of nuclear researcher Frederick deHoffman, Los Alamos weapons specialist Theodore Taylor and theoretical physicist Freeman Dyson. Largely fueled by Dyson, Orion’s aim was to build a spacecraft equipped with atomic bombs, that would propel the rocket further and further into space through a series of well-timed explosions (nuclear propulsion). The partial test ban treaty of 1963 ended the grandiose project, which remains classified to this day.

Ascension is the seamless fictional transition borne of asking “what if” questions about the erstwhile Project Orion. What if it never ended? What if it was still ongoing? What would be the psychological ramifications of entire generations of people born, raised and living on a closed vessel? Is human habitation of other planets an uncertainty or inevitability? And so Project Orion continued on as Project Ascension, under the hands of Abraham Enzmann. A crew of 600 was sent off into space not knowing the fate of humanity, frozen in time, and as far as they know — all that would be left of mankind.

Ascension carries on in the vein of stylish series such as Caprica, Helix and Defiance, with sleek sci-fi gadgetry and a spaceship capable of mimicking an entire world (including a beach!) for 100 years. This is no dilapidated, aging Battlestar Galactica. However, because time is frozen in the 1960s, all technology, clothes and cultural collections reflect that era — think Mad Men in space. Nostalgia reigns with references to the Space Race via speeches from President Kennedy, along with film and television cornerstones of that era.

51 years into the mission, on the evening of the annual launch party celebration, a kind of Ascension independence day, the unthinkable happens: the first ever murder onboard the ship. Captain William Denninger puts first officer Aaron Gault in charge of investigating. Soon, the motives for the murder become convoluted amidst internal politics and the looming “Insurrection,” a point of no return in which communication with Earth is no longer possible.

This year’s space epic Interstellar explored the science of traveling 10 billion light years away from Earth – ambitiously but not without factual fault. And to be sure, Ascension will address the challenges and physics of nuclear propulsion to the far reaches of space, starting with a radiation storm midway through the first episode. But rather than bogging itself down in the astrophysical minutiae of space travel, Ascension smartly focuses on the human drama and existential questions such a voyage would incur, precisely what made Battlestar Galactica such compelling sci-fi television. Would there be internal psychological ramifications to this journey? All residents of the ship seem to go through an adolescent period termed “The Crisis,” where they come to grips with the fact that they have no future, and a pre-determined fate. Furthermore, the murder victim’s young sister appears to be a “seer” with telekinetic insight into the nefarious inner workings of the ship.

Would there be class division and political turmoil aboard such a confined community? There is a decidedly troublesome rift between the ranking officers of the upper quarters and the “Below Deckers”: butchers, steelworkers and other blue-collar craftsmen that appear on the edge of a revolt. Compounding their efforts are the Captain’s wife, Viondra Denninger (whom fans will recognize as Cylon Number Six from BSG), a cunning, manipulative power broker and the man seeking to wrestle control of the ship from her husband. Back on Earth, we meet Harris Enzmann, the son of the dying Project Ascension founder. Seemingly a low level government engineer, nor remotely interested in preserving his father’s legacy, his role in Project Ascension is convoluted yet significant.

Project Ascension is indeed an experiment critical for human survival — just not the one anyone onboard thinks it is. Amidst an awakened collective imagination about space exploration, including 2015’s IMAX Mars mission movie Journey To Space, this is one sci-fi mission worth taking.

View a trailer for Ascension:

Ascension is a three-day mini-series event on SyFy Channel, beginning Monday, December 15.

~*ScriptPhD*~

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire us for creative content development.

Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

]]>

In 2007, new NASA research suggested that underneath the vast ice sheaths of Jupiter’s moon Europa lay oceanic water, which is a key element to support life. The Galileo probe, which had been orbiting the moons of Jupiter since December of 1995, was constantly orbiting and swooshing near the sixth largest moon in the solar system, collecting pictures and data that could prove the existence of liquid water. Then in 2011, scientists hit a proverbial jackpot—evidence for two liquid lakes the volume of the North American Great Lakes underneath a region of jumbled ice blocks termed the ‘Conamara Chaos.’ Even in the wake of such exciting discoveries, critical budget cuts severely threatened NASA’s space program, including the Mars rover and Cassini spacecraft orbiting Saturn. This same time frame gave concurrent rise to private space travel, led by the commercial venture Virgin Galactic and ambitious research company Space X. The merger of limitless industry resources with the possibility of uncovering alien life seems like a perfect Hollywood pitch. Such is the scenario explored in the brilliant documentary-style sci-fi thriller Europa Report. A full ScriptPhD review under the “continue reading” cut.

First conceptualized in 2009, prior to NASA’s landmark discovery of Jupiter’s large lakes, Europa Report explores the fundamental question driving space discovery: “Are we alone?” With private funds and advanced technology at their disposal, the fictitious Europa Ventures space exploration company enlists seven brilliant voyagers for the groundbreaking “Europa Mission,” the first venture beyond Earth’s orbit since 1972. Masterminded by company founders Drs. Samantha Unger and Tarik Pamuk, who also narrate the film and drive the story forward in current time, the multi-year investigative mission (16 months on Europa alone!) would combine state-of-the-art science with modern entertainment. Europa Report’s first act parlays the mundane lull of life in space—exercise to stave off atrophy, recycling urine for distilled water, ship engineers Andrei Blok and James Corrigan bickering in close quarters—overshadowed by the hints of future tragedy.

Indeed, approximately six months into their journey, the Europa Mission communications with ground control are cut off by an unexpected solar storm. From here, the film cleverly seesaws between the present and chronological flashbacks, as the crew bravely decides to press on with their journey. The film’s tempo subtlely, but effectively, picks up with a series of tragic events that affect the crew. When the ship is stranded on the moon’s surface due to heat beneath the ice surface, the crew take drastic steps, led by pilot Rosa Dasque to ensure that the precious data they collected is not for naught.

Europa Report is easily the most realistic depiction of travel and life in space since 2009’s Moon and the 1960s standard-bearer 2001: A Space Odyssey. Committed to the accuracy of its sets, shuttle, space imagery and scientific data, Europa Report relied on heavy consultation with NASA/Jet Propulsion Laboratory, SpaceX and other scientific leaders from the planning and execution of the mission to what the surface of Europa would look like. Filmmakers worked with astrobiologists to conceive theoretical, yet plausible, Europa life forms from the bioluminescent ones that exist deep in the Earth’s oceans. The depiction of the Europa landing is one of the most exciting science movie moments I have ever seen on screen.

With the help of NASA and SpaceX, set designer Eugenio Caballero built a fully authentic spaceship, including living quarters, control area and zero gravity wirework. After production was complete, the visual effects team replicated the Europa exterior environment based on data and imagery collected during the Galileo mission. Perhaps as a result, some of the film’s strongest sequences occur when Dr. Katya Petrovna tenuously ventures on the icy surface to collect data and explore the surroundings, leading to the heart-stopping conclusion that both seals the team’s ultimate fate and reaffirms the value of their mission.

“This project felt like a unique opportunity to do something plausible but forward thinking, somewhere between NASA and Star Trek,” said Ben Browning, whose company Wayfare Entertainment developed the film.

Europa Report is constructed to feel like a documentary or voyeuristic web stream of a very real (and altogether possible) scientific experiment. That a reality show would be borne of such an undertaking is a foregone conclusion. Nevertheless, the film leaves several important overarching existential questions that we must examine in our inevitable quest to search the galaxy for extra-terrestrial life. Even if we find life forms in the outer galaxy, do we really want to know what’s out there? Or perturb it? In the case of Europa Report, a terrifying conclusion conjures up as many fears as it answers exciting possibilities. Secondly, as technology makes extreme space travel to previously-unreached distances possible, we must never forget the element of danger that fuels the bravery of the astronauts and scientist that

undertake these endeavors. Lastly, is the commercialization of space a good idea? In the wake of celebrities buying shuttle rides into Earth’s orbit and space ventures funded by billionaires, who will maintain regulatory oversight and scientific integrity?

Ultimately, it’s inevitable that there will be a real-life mission to Europa, or even beyond. And an even bigger possibility that a groundbreaking discovery of current life in outer space will be made. But until that day, Europa Report unveils a grand science experiment before our eyes and perhaps, even a glimpse into the future.

View a trailer for Europa Report:

Europa Report goes into limited theatrical release on August 2, 2013 and is available On Demand.

~*ScriptPhD*~

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development.

Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

]]>

In the year 2042, time travel has not yet been invented. But by the year 2072, that is no longer the case. Nevertheless, it is outlawed, inaccessible to all but the most powerful and violent gangs in an economically repressed dystopia. Due to scientific advances of that era, it is impossible to dispose of a body without a trace, so the criminal gangs use the time travel to execute their “trash,” sending the bodies back in time to be executed by hit men called Loopers. The body vanishes from the future, but never existed in the present. Unless something goes terribly awry. Such is the setup of Rian Johnson’s bleak, brilliant sci-fi film Looper, a shrewd commentary on how we use technology, the value of a human life and whether a destiny can be changed. It is easily the best sci-fi film since 2010’s Inception, and surely one of the best of this year in any genre. Full ScriptPhD review, below.

Joe (Joseph Gordon-Levitt) is a Looper, a very desirable and profitable position in a time over-run with vagrant raids, poverty, hopelessness and violence. The job has a 30-year finite time span, at which time the Looper is sent back into time to be exterminated, and a younger, genetically identical version of him starts job all over again. This is called “closing the loop.” The consequences, shown early in the film, of not closing the loop are dire, both for the younger Looper and his older counter-part. But Joe, an emotionally detached junkie, treats his executions with a regimented ennui. Until one day, when a loop fails to show up at the expected hour. In a split second, Joe recognizes the man as the older version of himself (Bruce Willis), and the brief hesitation allows Old Joe to escape, unleashing the fury of the warlords on both of them across the boundaries of time.

The future painted by Johnson is noir-lugubrious but stops short of the over-the-top post-apocalyptic dreariness of Blade Runner or Children of Men. Instead, the issues of social equality, money and humanity that we struggle with today are exaggerated under the umbrella of traditional sci-fi existentialism. The Looper future is also one filled with abject unfairness. Hungry vagrants that steal food out of desperation are shot immediately by armed citizens. A mobster (Jeff Daniels) sent from the future to run the loopers quenches his boredom by running the city with tyranny, leaving the dirty work of closing loops to violent thugs. Worst of

all is the news from the future of the appearance of a tyrannical warlord named The Rainmaker, who is closing all the loops one by one.

At first, the relationship between Young Joe and Old Joe is antagonistic. All Old Joe wants to do is survive and warn his younger counterpart not to repeat the mistakes he made, especially trying to avoid the death of his wife. All Young Joe wants to do is close his loop, collect the money and make right with the mob. But they grow to grudgingly protect one another amidst a greater goal—finding and eliminating the younger version of The Rainmaker in the present. A series of mysterious maps and codes lead Young Joe to a farmhouse where a young woman, Sarah (Emily Blunt), and her son Cid (Pierce Ganon) are hiding out. As it dawns on Young Joe that Cid is the Young Rainmaker, he wrestles with whether a deleterious future can truly be avoided either for himself or Cid, all while chasing Old Joe and being chased himself.

From the sci-fi element, Looper craftily wedges evolution of technology in a future world not so unlike our own. There is time travel, a quirky genetic mutation that affects 10% of the population (they can levitate quarters!) and expected audiovisual upgrades to touch-screen technology. But there are also familiar elements—books, records, refrigerators and even cars—that make these developments feel natural and real. Even time travel is treated not as an exotic luxury but a quotidian burden. The one and only scene of time travel in the film shows a rather simple metal tube that transports people to a time point in an empty field.

Whether time travel is actually possible in reality is a point of continuing contention with physicists. First referenced in H.G. Wells’s The Time Machine, time travel has been a steady staple of the sci-fi canon, but it wasn’t until Albert Einstein unraveled the four dimensions of space with his Theory of Relativity in 1915 that the notion seemed tenable. And of course, in theory, time travel is a very real occurrence, since we know that time passes more slowly the closer you approach the speed of light. Physicists such as Stephen Hawking have grappled with other time-space phenomena such as wormholes and quantum theory that might facilitate time jumping. Most scientists, however, are unified in their belief that if a time machine were ever built, it would be used exclusively for going forward in time, and not backwards, for many of the same quandaries proposed in Looper, particularly whether you can change the course of events that are destined to happen in the future.

But Looper doesn’t contend with any of that. It just assumes physicists have solved these hurdles and focuses on a smart, intricate, well-written story. It’s a film that treats its audience with respect, asking for patience in the more complicated plot points, and rewarding it with a satisfying, shocking crescendo worthy of its metaphysical journey. Indeed, Looper might be the first film of the 21st Century to provide a truly real purview into the ethical quandaries, and frightening realities, that time travel might present to us should it ever come to pass.

Preview trailer here:

Looper goes into release nationwide on September 28, 2012.

~*ScriptPhD*~

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development.

Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

]]>

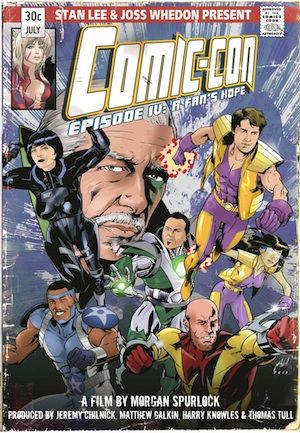

This past weekend, over 130,000 people descended on the San Diego Convention Center to take part in Comic-Con 2012. Each year, a growing amalgamation of costumed super heroes, comics geeks, sci-fi enthusiasts and die-hard fans of more mainstream entertainment pop culture mix together to celebrate and share the popular arts. Some are there to observe, some to find future employment and others to do business, as beautifully depicted in this year’s Morgan Spurlock documentary Comic-Con Episode IV: A Fan’s Hope. But Comic-Con San Diego is more than just a convention or a pop culture phenomenon. It is a symbol of the big business that comics and transmedia pop culture has become. It is a harbinger of future profits in the entertainment industry, which often uses Comic-Con to gauge buzz about releases and spot emerging trends. And it is also a cautionary tale for anyone working at the intersection of television, film, video games and publishing about the meteoric rise of an industry and the uncertainty of where it goes next. We review Rob Salkowitz’s new book Comic-Con and the Business of Pop Culture, an engaging insider perspective on the convergence of geekdom and big business.

Comic-Con wasn’t always the packed, “see and be seen” cultural juggernaut it’s become, as Salkowitz details in the early chapters of his book. In fact, 43 years ago, when the first Con was held at the US Grant hotel in San Diego, led by the efforts of comics superfan Shel Dorf, only 300 people came! In its early days, Comic-Con was a casual place where the titans of comics publishers such as DC and Marvel would gather with fans and other semi-professional artists to exchange ideas and critique one another’s work in an intimate setting. In fact, Salkowitz, a long-time Con attendee who has garnered quite a few insider perks along the way over the years, recalls that his early days of attendance were not quite so harried and frantic. The audience for Comic-Con steadily grew until about 2000, when attendance began skyrocketing, to the point that it now takes over an entire American city for a week each year. Why did this happen? Salkowitz argues that this time period is when a quantum leap shift occurred away from comic books and towards comics culture, a platform that transcends graphic novels and traditional comic books and usurps the entertainment and business matrices of television, film, video games and other “mainstream” art. Indeed, when ScriptPhD last covered Comic-Con in 2010, even their slogan changed to “celebrating the popular arts,” a seismic shift in focus and attention. (This year, Con organizers made explicit attempts to explore the history and heritage partially in order to assuage purists who argue that the event has lost sight of its roots.) In theory, this meteoric rise is wonderful, right? With all that money flowing, everyone wins! Not so fast.

Lost amidst the pomp and circumstance of the yearly festivities is the fact that within this mixed array of cultural forces, there are cracks in the armor. For one thing, comics themselves are not doing well at all. For example, more than 70 million people bought a ticket to the 2008 movie The Dark Knight, but fewer than 70,000 people bought the July 2011 issue of Batman: The Dark Knight. Salkowitz postulates that we may be nearing the unimaginable: a “future of the comics industry that does not include comic books.” To unravel the backstory behind the upstaging of an industry at its own event, Salkowitz structures the book around the four days of the 2011 San Diego Comic-Con. In a rather clever bit of exposition, he weaves between four days of events, meetings, exclusive parties, panels of various size and one-on-one interactions to take the reader on a guided tour of Comic-Con, while in the process peeling back the layers of transmedia and business collaborations

that are the underbelly of the current “peak geek” saturation. A brief divergence to the downfall of the traditional publishing industry, including bookstores (the traditional sellers of comics), the reliance of comics on movie adaptations and the pitfalls of digital publication is a must-read primer for anyone wishing to work in the industry. Even more strapped are merchants that sell rare comics and collectibles on the convention floor. Often relegated to the side corners with famous comics artists so that entertainment conglomerates can occupy prime real estate on the floor, many dealers struggle just to break even. Among them are independent comics, self-published artists, and “alternative” comics, all hoping to cash in on the Comic-Con sweepstakes. Comics may be big business, but not for everyone. Forays into the world of grass-roots publishing, the microcosm of the yearly Eisner Awards for achievement in comics and the alternative con within a Con called Trickster (a more low-key networking event that harkens to the days of yore) all remind the reader of the tight-knit relationship that comics have with their fan base.

In many ways, the comics crisis that Salkowitz describes is not only very real, but difficult to resolve. The erosion of print media is unlikely to be reversed, nor is the penchant towards acquiring free content in the digital universe. Furthermore, video games, represent one of the biggest single-cause reasons for the erosion of comics in the last 20 years. Games such as Halo, Mass Effect, Grand Theft Auto and others, execute recurring linear storylines in a more cost-conscious three-dimensional interactive platform. On the other hand, there are also a myriad of reasons to be positive about the future of comics. The advent of tablets (notably the iPad) represents an unprecedented opportunity to re-establish comics’ popularity and distribution profits. Traditional and casual fans of comics haven’t gone anywhere, they’re just temporarily drowned out by the lines for the Twilight panel. A rising demographic of geek girls represents a potential growth segment in audience. And finally, a tremendous rise in popularity of traditional comics (even the classics) in global markets such as India and China portends a new global model for marketing and distribution. If superheroes are to continue as the mainstay of live-action media, the entertainment industry is highly dependent upon a viable, continued production of good stories. Movies need for comics to stay robust. The creativity and ingenuity that has been the hallmark of great comics continues to thrive with independent artists, some of whose work has gone viral and garnered publishing contracts.

Make no mistake, comics fans and enthusiastic geeks. Comic-Con and the Business of Pop Culture is very much a business and brand strategy book, centered around a very trendy and chic brand. There’s no question that casual fans and people interested in the more technical side of comics transmedia will find it an interesting, if at times esoteric, read. But for those working in (or aspiring to) the intersection of comics and entertainment, it is an essential read. Cautioning both the entertainment and comics industries against complacency against what could be a temporary “gold rush” cultural phenomenon, Salkowitz nevertheless peppers the book with salient advice for sustaining comics-based entertainment and media, while fortifying traditional comics and their creative integrity for the next generation of fans. The final portion of the book is its strongest; a hypothetical journey several years into the future, utilizing what he calls “scenario planning” to prognosticate what might happen. Comic-Con (and all the business that it represents) might grow larger than ever, an absolute phenomenon, might scale back to account for a diminishing fan interest, might stay the same or fraction into a series of global events to account for the growing overseas interest in traditional comics. Which one will come to fruition depends on brand synergy, fan growth and engagement, distribution with digital and interactive media, and a carefully cultivated relationship between comics audiences, creators and publishers. Salkowitz calls Comic-Con a “laboratory in which the global future of media is unspooling in real time.” What will happen next? Like any good scientist knows, experiments, even under controlled circumstances, are entirely unpredictable. See you in San Diego next year!

Rob Salkowitz is the cofounder and Principal Consultant of Seattle-based MediaPlant LLC and is the author of two other books, Young World Rising and Generation Blend. He also teaches in the Digital Media program at the University of Washington. Follow Rob on Twitter.

~*ScriptPhD*~

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development.

Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

]]>

Earlier this year, the Susan G. Komen Foundation made headlines around the world after their politically-charged decision to cut funding for breast cancer screening at Planned Parenthood caused outrage and negatively impacted donations. Despite reversing the decision and apologizing, many people in the health care and fund raising community feel that the aftermath of the controversy still dogs the foundation. Indeed, Advertising Age literally referred to it as a PR crisis. If all of this sounds more like spin for a brand rather than a charity working towards the cure of a devastating illness, it’s not far from the truth. Susan G. Komen For the Cure, Avon Walk For Breast Cancer and the Revlon Run/Walk For Women represent a triumvirate hegemony in the “pink ribbon” fundraising domain. Over time, their initial breast cancer awareness movement (and everything the pink ribbon stood for symbolically) has moved from activism to pure consumerism. The new documentary Pink Ribbons, Inc. deftly and devastatingly examines the rise of corporate culture in breast cancer fundraising. Who is really profiting from these pink ribbon campaigns, brands or people with the disease? How has the positional messaging of these “pink ribbon” events impacted the women who are actually facing the illness? And finally, has motivation for profit driven the very same companies whose products cause cancer to benefit from the disease? ScriptPhD.com’s Selling Science Smartly advertising series continues with a review of Pink Ribbons, Inc..

“We used to march in the streets. Now you’re supposed to run for a cure, or walk for a cure, or jump for a cure, or whatever it is,” states Barbara Ehrenreich, breast cancer survivor and author of Welcome to Cancerland, in the opening minutes of the documentary Pink Ribbons, Inc. Directed by Canadian filmmaker Lea Pool and based on the book Pink Ribbons, Inc.: Breast Cancer and the Politics of Philosophy by Samantha King, the documentary features in-depth interviews with leading authors, experts, activists and medical professionals. It also includes an important look at the leading players in breast cancer fundraising and marketing. The production crew filmed a number of prominent fundraising events across North America, using the upbeat festivities (where some didn’t even visibly show the word ‘cancer’) as the backdrop for exploring the “pinkwashing” of breast cancer through marketing, advertising and slick gimmicks. At the same time, showcasing well-meaning, enthusiastic walkers, runners and fundraisers is a double-edged sword and was handled with the appropriate sensitivity by the filmmakers. Pool wanted to “make sure we showed the difference between the participants, and their courage and will to do something positive, and the businesses that use these events to promote their products to make money.”

Often lost amidst the pomp and circumstance of these bright pink feel-good galas is that the origins of the pink ribbon are quite inauspicious. The original pink ribbon wasn’t even pink. It was a salmon-colored cloth ribbon made by breast cancer activist Charlotte Haley as part of a grass roots organization she called Peach Corps. From a kitchen counter mail-in operation, Haley’s vision grew to hundreds of thousands of supporters, so much so that it caught the attention of Estee Lauder founder Evelyn Lauder. The company wanted to buy the peach ribbon from Haley, who refused, so they simply rebranded breast cancer to a comforting, reassuring, non-threatening color: bright pink. And before our very eyes, a stroke of marketing genius was born.

As the pink ribbon movement took hold of the fundraising community, the money started to spill over into mainstream advertising, adorning everything from the food we eat to the clothes we wear, all under the auspices of philanthropy. In theory, people should feel great about buying products that return some of their profits for such a great cause. In practice, many of these campaigns simply throw a bright pink cloak over false, if not cynical, advertising. Take Yoplait’s yearly “Save Lids to Save Lives” campaign:

For every lid you save from a Yoplait yogurt (and mail in, using a $0.44 stamp, mind you!), they will donate 10 cents to breast cancer research. If you ate three yogurts per day for fourth months, you will have raised a grand total of $36 for breast cancer research, but spent more on stamps and in environmental shipping waste. Not as impressive when you break it down, eh?

A recent American Express campaign called “Every Dollar Counts” pledged that every purchase during a four month period would incur a one cent donation to breast cancer research. Unfortunately, they never quantified donations commensurate to spending, so that meant whether you charged a pack of gum or a big screen TV to your AmEx, they would donate a penny. The breast cancer community was so outraged by this hubris, they staged a successful campaign to rescind the ads. The fact is, the above examples demonstrate that pink ribbons have become an industry, with demographics and talking points, just like everything else. Pinkwashing campaigns tend to target middle class, ultra-feminine white women. Why? Because they are typical targets that move the products these industries are trying to sell. Take the NFL’s recent pink screening campaign. Well-meaning or not, it came amidst a series of crimes and violence by NFL players, some of which was domestic in nature. One can imagine that players adorned in hot pink gear would have been a smart way to mollify its rather impressive female fanbase.

As Ehrenreich states in the documentary, the collective effect of this marketing has been to soften breast cancer into a pretty, pink and feminine disease. Nothing too scary, nothing too controversial. Just enough to keep raising money that goes… somewhere. Take a look at the recent chipper television campaign for the Breast Cancer Centre of Australia:

While some of the breast cancer-related branding and pink sponsorships mislead through good intentions, others are a dangerous bold-faced lie. Some of the very companies that sponsor fundraising events and make money off of pink revenue either make deleterious products linked to cancer or stand to profit from treatment of it. Revlon, sponsors of the Run/Walk for Women, are manufacturers of many cosmetics (searchable on the database Skin Deep) that are linked to cancer. The average woman puts on 12 cosmetics products per day, yet only 20% of all cosmetics have undergone FDA examination and safety testing. The pharmaceutical giant Astra Zeneca can’t seem to decide if it’s for or against cancer. They produce the anti-estrogen breast cancer drug Tamoxifen, yet also manufacture the pesticide atrazine (under the Swiss-based company Syngenta), which has been linked to cancer as an estrogen-boosting compound. Breast cancer history month (October) is nothing more than a PR stunt that was invented by a marketing expert at… drumroll please… Astra Zeneca! Their goal was to promote mammography as a powerful weapon in the war against breast cancer. But as the American arm of the largest chemical company in the world, the reality is that Astra Zeneca was and is benefiting from the very illness it was urging women to get screened for. Perhaps the most audacious example of them all is pharmaceutical giant Eli Lilly. Sponsors of cancer research and treatment, both in medicine and the community, Lilly produced the cancer and infertility causing DES (diethylstilbestrol), and currently manufactures rBGH, an artificial hormone given to cows to make them produce more milk. rBGH has been linked to breast cancer and a host of other health problems. These strong corporate links in many ways explain the uplifting, happy, sterile messaging behind the pink ribbon. Corporations are, quite bluntly, making money off of marketing cancer, so if they don’t put a smiley face on the disease, they will alienate their customers and the conglomerate businesses pouring money into these campaigns.

Juxtaposed with the uplifting, bombastic, bright pink backdrop of the various cancer fundraisers and rallies, Pink Ribbons, Inc. quietly profiles the IV League, an Austin, TX-based support group for metastatic breast cancer. The women meet on a regular basis to share stories, help each other cope and accept the rigors of the disease and realities of dying. Many of the group members interviewed found current breast cancer campaign marketing offensive, tastelessly positive and falsely empowering (“If you just get screened and get mammograms and eat healthy, breast cancer can’t happen to you!”). The group, which has lost 10 members last year alone, is among a large faction of cancer sufferers that feel left out in the pinkwashing tide of marketing campaigns. Highlighting that sometimes you do get cancer because of no explanation, and sometimes you won’t respond to any treatment is a downer. It’s not the kind of uplifting story that advertising campaigns are built around, leaving the women feeling as if they’re living alone with the fact that they are dying. “You’re the angel of death,” remarks IV Leaguer Jeanne Collins. “You’re the elephant in the room. And they’re learning to live and you’re learning to die.” By utilizing powerful messaging keywords like BATTLE, WAR and SURVIVOR, cancer foundations and brands are subliminally putting down those who didn’t survive. And there are many who don’t survive — someone dies of breast cancer every 69 seconds. Are they suggesting that people who died or didn’t respond to treatment simply didn’t try hard enough? One of the most poignant moments in the film was an IV League Stage 4 cancer patient, probably weeks or months from her death: “You can die in a perfectly healed state.”

Although Pink Ribbons, Inc. is a sobering polemic against the mindless trivialization of commercializing breast cancer and even misdirecting funds from where they can be most helpful, it is not a hopeless film. Far from projecting pessimism, the film showcases the tremendous willpower and manpower that these three-day walks engender. It is simply misdirected. If hundreds of thousands of women and men can be motivated to fundraise, walk, run and (in some cases) jump out of planes, the effort is absolutely there to stop breast cancer. “Do something besides worry to make a difference,” concludes Barbara Brenner. “We have enormous power, if only we’d use it.” Director Lea Pool hopes that the film will encourage people to “be more critical about our actions and stop thinking that by buying pink toilet paper we’re doing what needs to be done. I don’t want to say that we absolutely shouldn’t be raising money. We are just saying ‘Think before you pink.'”

Watch the trailer for Pink Ribbons, Inc. here:

Pink Ribbons, Inc. goes into wide release in theaters nationwide June 8, 2012 and was released on DVD in September of 2012.

~*ScriptPhD*~

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development.

Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

]]>

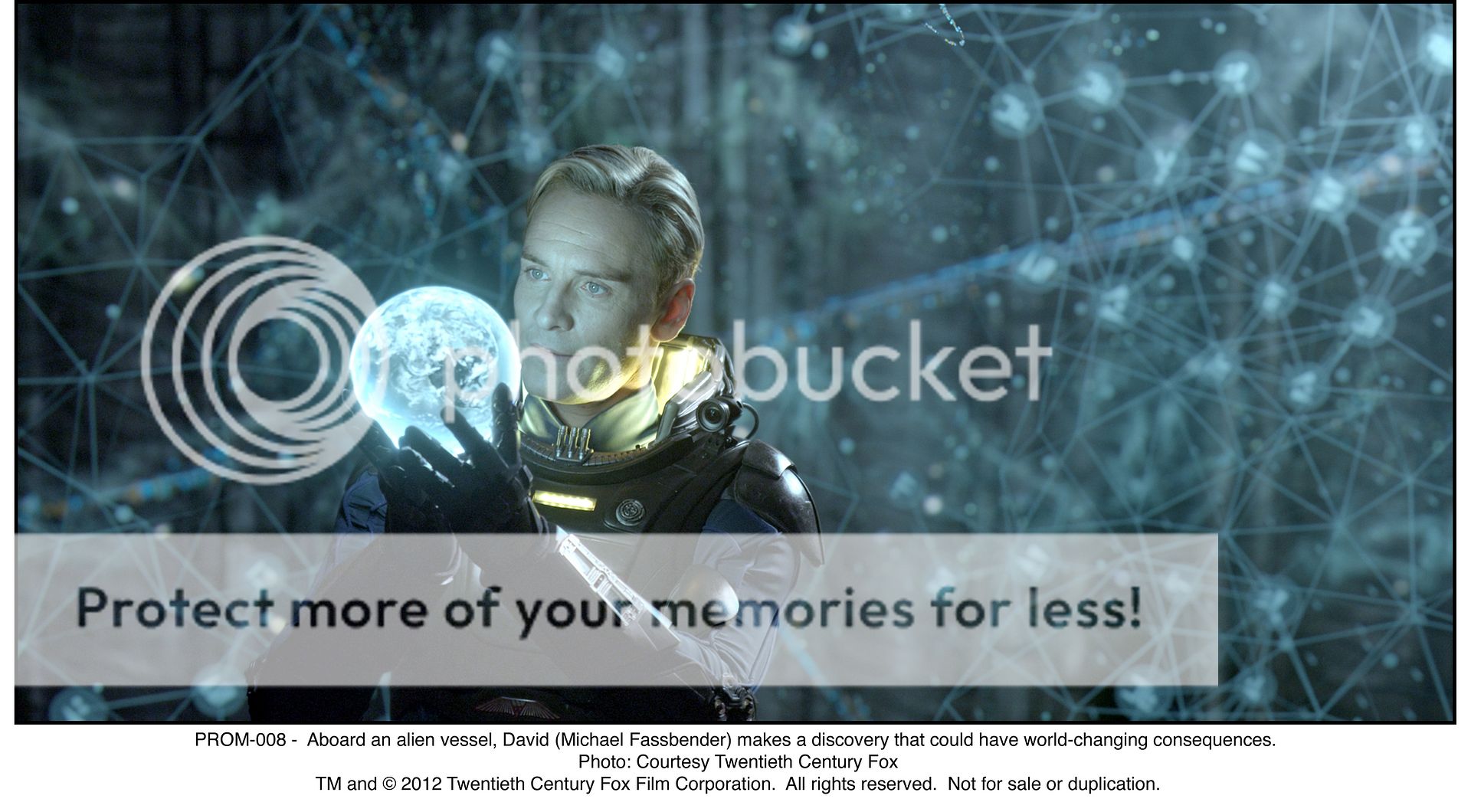

It has been three decades since Ridley Scott’s acclaimed sci-fi masterpiece Blade Runner practically reinvented the genre, and he has not made another sci-fi film since. “The reason I haven’t made another sci-fi film in so may years,” he says “is because I haven’t come across anything worthwhile for me to do with enough truth, originality and strength. Prometheus has all three.” With such heightened expectations, one would expect a bold, daring, all-encompassing storyline from Scott. Loosely based on elements from Alien, and originally intended as a prequel to that film, Prometheus meets many of those expectations, especially in visual and action content, while falling short on others. Full ScriptPhD review, under the “continue reading” cut.

Set 80 years in the future, a team of archaeologists discovers a series of cave etchings with a clue to the origins of mankind on Earth—a far-away planet in the darkest corners of the Universe. Commissioned by the corporate conglomerate Weyland Corporation, the $1 trillion scientific exploratory journey is originally intended to meet our makers in their native land. But when the team makes the shocking discovery that their makers’ paradise is a way station for a dangerous experiment in bioengineering, they begin the fight of their life to save humanity.

Interspersed within this non-stop intergalactic thrill ride are a series of conflicts between the crew members that challenge some of our most cherished scientific and philosophical ideas, conflicts we may ourselves be forced to address in the near future. The sterile, corporate (and somewhat surprisingly selfish) interests of the journey, funded by enigmatic Peter Weyland and carried out by Weyland Industries executive Meredith Vickers are in stark contrast to the spirit of scientific exploration for the sake of discovery and learning. The mission’s lead scientists are archetypes for the conflict of faith versus science. Elizabeth Shaw is deeply religious, and views the mission as a chance to meet the Gods, to affirm her faith and everything she believes in. Her partner, both in the lab and personally, Charlie Holloway is a classic adventurous scientist who is on the journey to push the envelope in the quest for answers. Finally, rounding out

the crew of 17 scientists is David, a human-replica android servant of superior intelligence created by the Weyland Corporation. David is an amalgamation of virtually every artificial intelligence character sci-fi has ever created, from Hal to C-3PO to the Terminator. Originally manufactured to tend to the ship during the two-year journey and to gather intelligence, David is nevertheless acutely aware of his superiority over his human charges. He even has the will to help them figure out the nefarious scheme of the alien predecessors and fight a battle for their survival. Responding to Holloway’s flippant response that humans made David simply because they could, he retorts: “Imagine how disappointed you’d be if your makers gave you the same response?”

Scott’s commitment to the grand scope of

Prometheus rewards the audience with a technological and engineering masterpiece of science fiction, starting with the visually arresting sets and action sequences. So extraordinary are the special effects of the scientific exploration of the alien planet and consequent battles, one would falsely assume they are CGI. But Scott built enormous sets and shot the majority of the film live in three dimensions. One production crew member called it the “greatest alien playground in the world.” The state-of-the-art spacecraft, modeled after current NASA and European Space Agency designs, was constructed with every piece of technology that would be necessary to probe the outer corners of the galaxy. Techno-geeks will salivate over sleek gadgetry like the self-operating medical pod, research labs capable of immediately isolating and sequencing single strands of DNA, travelling “mind pop” mapping devices that can isolate life, not to mention sleep-state pods where the scientists are suspended for their two-year journey. Prometheus gives a credible peek into what our science and technology capabilities will be like a hundred years from now.

Ultimately, for all of its ambition and far-reaching scope, Prometheus eventually buckles under its own weight of self-importance. The existential questions it is asking are sci-fi staples. Who are we? Where do we come from? How do we reconcile science and religion in our quest to define our identities? And finally, embodied by the advanced-technology android David, what are the parameters of responsibility in the creation of life? And what is the reason for the frailty about when and why it begins and ends? Unfortunately, the film only dabbles enough with each to titillate without ever providing fulfilling answers. The audience may finish the Prometheus quest philosophically unsatisfied, but the journey there is still an action-packed, viscerally stunning sci-fi ride.

Prometheus goes into theaters nationwide on June 11, 2012.

View the trailer:

~*ScriptPhD*~

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development.

Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

]]>

Every July, hundreds of thousands of fans descend upon the city of San Diego for a four-day celebration of comics, sci-fi, popular arts fandom and (growingly) previews of mainstream television and film blockbusters. What is this spectacular nexus of nerds? Comic-Con International, of course! From ScriptPhD’s comprehensive past coverage, one can easily glean the diversity of events, guests and panels, with enormous throngs patiently queueing to see their favorites. But who are these fans? Where do they come from? What kinds of passions drive their journeys to Comic-Con from all over the world? And what microcosms are categorized under the general umbrella of fandom? Award-winning filmmaker Morgan Spurlock attempts to answer these questions by crafting the sweet, intimate, honest documentary-as-ethnography Comic-Con Episode IV: A Fan’s Hope. Through the archetypes of five 2009 Comic-Con attendees, Spurlock guides us through the history of the Con, its growth (and the subsequent conflicts that this has engendered), and most importantly, the conclusion that underneath all of those Spider-Man and Klingon costumes, geeks really do come in all shapes, colors and sizes. For full ScriptPhD review, click “continue reading.”