From its earliest inceptions, science fiction has blurred the line between reality and technological fantasy in a remarkably prescient manner. Many of the discoveries and gadgets that have integrated seamlessly into modern life were first preconceived theoretically. More recently, the technologies behind ultra-realistic visual and motion capture effects are simultaneously helping scientists as research tools on a granular level in real time. The dazzling visual effects within the time-jumping space film Interstellar included creating original code for a physics-based ultra-realistic depiction of what it would be like to orbit around and through a black hole. Astrophysics researchers soon utilized the film’s code to visualize black hole surfaces and their effects on nearby objects. Virtual reality, whose initial development was largely rooted in imbuing realism into the gaming and video industries, has advanced towards multi-purpose applications in film, technology and science. The Science Channel is augmenting traditional programming with a ‘virtual experience’ to simulate the challenges and scenarios of an astronaut’s journey into space; VR-equipped GoPro cameras are documenting remote research environments to foster scientific collaboration and share knowledge; it’s even being implemented in health care for improving training, diagnosis and treatment concepts. The ability to record high-definition film of landscapes and isolated areas with drones, which will have an enormous impact on cinematography, carries with it the simultaneous capacity to aid scientists and health workers with disaster relief, wildlife conservation and remote geomapping.

The evolution of entertainment industry technology is sophisticated, computationally powerful and increasingly cross-functional. A cohort of interdisciplinary researchers at Northwestern University is adapting computing and screen resolution developed at DreamWorks Animation Studios as a vehicle for data visualization, innovation and producing more rapid and efficient results. Their efforts, detailed below, and a collective trend towards integration of visual design in interpreting complex research, portends a collaborative future between science and entertainment.

Not long into his tenure as the lead visualization engineer at Northwestern University’s Center For Advanced Molecular Imaging (CAMI), Matt McCrory noticed a striking contrast between the quality of the aesthetic and computational toolkits used in scientific research versus the entertainment industry. “When you spend enough time in the research community, with people who are doing the research and the visualization of their own data, you start to see what an immense gap there is between what Hollywood produces (in terms of visualization) and what research produces.” McCrory, a former lighting technical director at DreamWorks Animation, where he developed technical tools for the visual effects in Shark Tale, Flushed Away and Kung Fu Panda, believes that combining expertise in cutting-edge visual design with emerging tools of molecular medicine, biochemistry and pharmacology can greatly speed up the process of discovery. Initially, it was science that offered the TV and film world the rudimentary seeds of technology that would fuel creative output. But the TV and film world ran with it — so much so, that the line between science and art is less distinguishable than in any other industry. “We’re getting to a point [on the screen] where we can’t discern anymore what’s real and what’s not,” McCrory notes. “That’s how good Hollywood [technology] is getting. At the same time, you see very little progress being made in scientific visualization.”

What is most perplexing about the stagnant computing power and visualization in science is that modern research across almost all fields is driven by extremely large, high-resolution data sets. A handful of select MRI imaging scanners are now equipped with magnets ranging from 9.4 to 11.75 Teslas, capable of providing cellular resolution on the micron scale (0.1 to 0.2 millimeters versus 1.5 Tesla hospital scanners, at 1 millimeter resolution) and cellular changes on the microsecond scale. The ultra high-resolution imaging provides researchers with insight into everything from cancer to neurodegenerative diseases. While most biomedical drug discovery today is engineered by robotics equipment, which screens enormous libraries of chemical compounds for activity potential around the clock in a “high-throughput” fashion — from thousands to hundreds of thousands of samples — data must still be analyzed, optimized and implemented by researchers. Astronomical observations (from black holes to galaxies colliding to detailed high-power telescope observations in the billions of pixels) produce some of the largest data sets in all of science. Molecular biology and genetics, which in the genomics era has unveiled great potential for DNA-based sub-cellular therapeutics, has also produced petrabytes of data sets that are a quandary for most researchers to store, let alone visualize.

Unfortunately, most scientists can’t allocate dual resources to both advancing their own research and finding the best technology with which to optimize it. As McCrory points out: “In a field like chemistry or biology, you don’t have people who are working day and night with the next greatest way of rendering photo-realistic images. They’re focused on something related to protein structures or whatever their research is.”

The entertainment industry, on the other hand, has a singular focus on developing and continuously perfecting these tools, as necessitated by proliferation of divergent content sources, screen resolution and powerful capture devices. As an industry insider, McCrory appreciates the competitive evolution, driven by an urgency that science doesn’t often have to grapple with. “They’ve had to solve some serious problems out there and they also have to deal with issues involving timelines, since it’s a profit-driven industry,” he notes. “So they have to come up with [computing] solutions that are purely about efficiency.” Disney’s 2014 animated science film Big Hero 6 was rendered with cutting-edge visualization tools, including a 55,000-core computer and custom proprietary lighting software called Hyperion. Indeed, render farms at LucasFilm and Pixar consist of core data centers and state-of-the-art supercomputing resources that could be independent enterprise server banks.

At Northwestern’s CAMI, this aggregate toolkit is leveraged by scientists and visual engineers as an integrated collaborative research asset. In conjunction with a senior animation specialist and long-time video game developer, McCrory helped to construct an interactive 3D visualization wall consisting of 25 high-resolution screens that comprise 52 million total pixels. Compared to a standard computer (at 1-2 million pixels), the wall allows researchers to visualize and manage entire data sets acquired with higher-quality instruments. Researchers can gain different perspectives on their data in native resolution, often standing in front of it in large groups, and analyze complex structures (such as proteins and DNA) in 3D. The interface facilitates real-time innovation and stunning clarity for complex multi-disciplinary experiments. Biochemists, for example, can partner with neuroscientists to visualize brain activity in a mouse as they perfect drug design for an Alzheimer’s enzyme inhibitor. Additionally, 7 thousand in-house high performing core servers (comparable to most studios) provide undisrupted big data acquisition, storage and mining.

Could there be a day where partnerships between science and entertainment are commonplace? Virtual reality studios such as Wevr, producing cutting-edge content and wearable technology, could become a go-to virtual modeling destination for physicists and structural chemists. Programs like RenderMan, a photo-realistic 3D software developed by Pixar Animation Studios for image synthesis, could enable greater clarity on biological processes and therapeutics targets. Leading global animation studios could be a source of both render farm technology and talent for science centers to increase proficiency in data analysis. One day, as its own visualization capacity grows, McCrory, now pushing pixels at animation studio Rainmaker Entertainment, posits that NUViz/CAMI could even be a mini-studio within Chicago for aspiring filmmakers.

The entertainment industry has always been at the forefront of inspiring us to “dream big” about what is scientifically possible. But now, it can play an active role in making these possibilities a reality.

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development. Follow us on Twitter and Facebook. Subscribe to our podcast on SoundCloud or iTunes.

Ray Bradbury, one of the most influential and prolific science fiction writers of all time, has had a lasting impact on a broad array of entertainment culture. In his canon of books, Bradbury often emphasized exploring human psychology to create tension in his stories, which left the more fantastical elements lurking just below the surface. Many of his works have been adapted for movies, comic books, television, and the stage, and the themes he explores continue to resonate with audiences today. The notable 1966 classic film Fahrenheit 451 perfectly captured the definition of a futuristic dystopia, for example, while the eponymous television series he penned, The Ray Bradbury Theatre, is an anthology of science fiction stories and teleplays whose themes greatly represented Bradbury’s signature style. ScriptPhD.com was privileged to cover one of Ray Bradbury’s last appearances at San Diego Comic-Con, just prior to his death, where he discussed everything from his disdain for the Internet to his prescient premonitions of many technological advances to his steadfast support for the necessity of space exploration. In the special guest post below, we explore how the latest Bradbury adapataion, the new television show The Whispers, continues his enduring legacy of psychological and sci-fi suspense.

Premiering to largely positive reviews, ABC’s new show The Whispers is based on Bradbury’s short story “Zero Hour” from his book The Illustrated Man. Both stories are about children finding a new imaginary friend, Drill, who wants to play a game called “Invasion” with them. The adults in their lives are dismissive of their behavior until the children start acting strangely and sinister events start to take place. Bradbury’s story is a relatively short read with just a few characters that ends on a chilling note, while The Whispers seeks to extend the plot over the course of at least one season, and to that end it features an expanded cast including journalists, policemen, and government agents.

The targeting of young, impressionable minds by malevolent forces is deeply disturbing, and it seems entirely plausible that parents would write off odd behavior or the presence of imaginary friends as a simple part of growing up. In both the story and the show, the adults do not realize that they are dealing with a very real and tangible threat until it’s too late. The dread escalates when the adults realize that children who don’t know each other are all talking to the same person. The fear of the unknown, merely hinted at in Bradbury’s story, will seem to be exploited to great effect during the show’s run.

When “Zero Hour” was written in 1951, America was in the midst of McCarthyism and the Red Scare, and the fear of Communism and homosexuality ran rampant. As the tensions of the Cold War grew, so too did the anxiety that Communists had infiltrated American society, with many of the most aggressively targeted individuals for “un-American” activities belonging to the Hollywood filmmaking and writing communities. Bradbury’s story shares with many other fictions of the time period a healthy dose of paranoia and fear around possession and mind control. Indeed, Fahrenheit 451, a parable about a futuristic world in which books are banned, is also a parable about the dangers of censorship and political hysteria.

The makers of The Whispers recognize that these concerns still permeate our collective consciousness, and have updated the story with modern subject matter, expanding the subject of our apprehension to state surveillance and abuse of authority. To wit, many recent films and shows have explored similar themes amidst the psychological ramifications of highly developed artificial intelligence and its ability to control and even harm humans. Our concurrent obsession with and fear of technology run amok is another topic explored by Ray Bradbury in many of his later works. The idea that those around us are participating in a grand scheme that will bring us harm still sows seeds of discontent and mistrust in our minds. For that reason, the concept continues to be used in suspense television and cinema to this day.

One of the reasons Bradbury’s work continues to serve as the inspiration for so much contemporary entertainment is his use of everyday situations and human oddities to create intrigue. One such example is a 5-issue series called Shadow Show based on Bradbury’s work, released in 2014 by comic book publisher IDW. Some of the best artists, writers and comics had agreed to participate in this project since Bradbury had such a huge influence in their writing and art. In this anthology, Harlan Ellison’s “Weariness” perfectly elicits Bradbury’s dystopia in which our main characters experience the universe’s end. The terrifying end of life as we know it is one of Bradbury’s recurring themes, depicted in writings like The Martian Chronicles. He rarely felt the need to set his stories in faraway galaxies or adorn them with futuristic gadgets. Most of his writing focussed on the frightening aspects of humans in quotidien surroundings, such as in the 2002 novel, Let’s All Kill Constance. Much of The Whispers takes place in an ordinary suburban neighborhood, and like many of his stories, what seems at first to be a simple curiosity, is hiding something much more complex and frightening.

Fiction that brings out the spookiness inherent in so many facets of human nature creates a stronger and more enduring bond with its audience, since we can easily deposit ourselves into the characters’ situations, and all of a sudden we find that we’re directly experiencing their plight on an emotional level. That’s always been, as Bradbury well knew, the key to great suspense.

Maria Ramos is a tech and sci-fi writer interested in comic books, cycling, and horror films. Her hobbies include cooking, doodling, and finding local shops around the city. She currently lives in Chicago with her two pet turtles, Franklin and Roy. You can follow her on Twitter @MariaRamos1889.

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development. Follow us on Twitter and Facebook. Subscribe to our podcast on SoundCloud or iTunes.

One of Walt Disney’s enduring lifetime legacies was his commitment to innovation, new ideas and imagination. An inventive visionary, Disney often previewed his inventions at the annual New York World’s Fair and contributed many technological and creative breakthroughs that we enjoy to this day. One of Disney’s biggest fascinations was with space exploration and futurism, often reflected thematically in Disney’s canon of material throughout the years. Just prior to his death in 1966, Disney undertook an ambitious plan to build a utopian “Community of Tomorrow,” complete with state-of-the-art technology. Indeed, every major Disney theme park around the world has some permutation of a themed section called “Tomorrowland,” first introduced at Disneyland in 1955, featuring inspiring Jules Verne glimpses into the future. This ambition is beautifully embodied in Disney Picttures’ latest release of the same name, a film that is at once a celebration of ideas, a call to arms for scientific achievement and good old fashioned idealistic dreaming. The critical relevance to our circumstances today and full ScriptPhD review below.

“This is a story about the future.”

With this opening salvo, we immediately jump back in time to the 1964 World’s Fair in New York City, the embodiment of confidence and scientific achievement at a time when the opportunities of the future seemed limitless. Enthusiastic young inventor Frank Walker (Thomas Robinson), an optimistic dreamer, catches the attention of brilliant scientist David Nix (Hugh Laurie) and his young sidekick Athena, a mysterious little girl with a twinkle in her eye. Through sheer curiosity, Frank follows them and transports himself into a parallel universe, a glimmering, utopian marvel of futuristic industry and technology — a civilization gleaming with possibility and inspiration.

“Walt [Disney] was a futurist. He was very interested in space travel and what cities were going to look like and how transportation was going to work,” said Tomorrowland screenwriter Damon Lindelof (Lost, Prometheus). “Walt’s thinking was that the future is not something that happens to us. It’s something we make happen.”

Unfortunately, as we cut back to present time, the hope and dreams of a better tomorrow haven’t quite worked out as planned. Through the eyes of idealistic Casey Newton (Britt Robertson), thrill seeker and aspiring astronaut, we see a frustrating world mired in wars, environmental devastation and selfish catastrophes. But Casey is smart, stubborn and passionate. She believes the world can be restored to a place of hope and inspiration, particularly through science. When she unexpectedly obtains a mysterious pin — which we first glimpsed at the World’s Fair — it gives her a portal to the very world that young Frank traveled to. Protecting Casey as she delves deeper into the mystery is Athena, who it turns out is a very special time-traveling recruiter. She distributes the pins to a collective of the smartest, most creative people, who gather in the Tomorrowland utopia to work and invent free of the impediments of our current society.

Athena connects Casey with a now-aged Frank (George Clooney), who has turned into a cynical, reclusive iconoclastic inventor (bearing striking verisimilitude to Nikola Tesla). Casey and Frank must partner to return to Tomorrowland, where something has gone terribly awry and imperils the existence of Earth. David Nix, a pragmatic bureaucrat and now self-proclaimed Governor of a more dilapidated Tomorrowland, has successfully harnessed subatomic tachyon particles to see a future in which Earth self-destructs. Unless Casey and Frank, aided by Athena and a little bit of Disney magic, intervene, Nix will ensure the self-fulfilling prophesy comes to fruition.

As the co-protagonist of Tomorrowland Casey Newton symbolizes some of the most important tenets and qualities of a successful scientist. She’s insatiably curious, in absolute awe of what she doesn’t know (at one point looking into space and cooing “What if there’s everything out there?”) and buoyant in her indestructible hope that no challenge can’t be overcome with enough hard work and out-of-the-box originality. She loves math, astronomy and space, the hard sciences that represent the critical, diverse STEM jobs of tomorrow, for which there is still a graduate shortage. That she’s a girl at a time when women (and minorities) are still woefully under-represented in mathematics, engineering and physical science careers is an added and laudable bonus. She defiantly rebels against the layoff of her NASA-engineer father and the unspeakable demolition of the Cape Canaveral platform because “there’s nothing to launch.” The NASA program concomitantly faces the tightest operational budget cuts (particularly for Earth science research) and the most exciting discovery possibilities in its history.

The juxtaposition of Nix and Walker, particularly their philosophical conflict, represents the pedantic drudgery of what much of science has become and the exciting, risky brilliance of what it should be. Nix is pedantic and rigid, unable or unwilling to let go of a traditional credo to embrace risk and, with it, reward. Walker is the young, bushy-tailed, innovative scientist that, given enough rejection and impediments, simply abandons their research and never fulfills their potential. This very phenomenon is occurring amidst an unprecedented global research funding crisis — young researchers are being shut out of global science positions, putting innovation itself at risk. Nix’s prognostication of inevitable self-destruction because we ignore all the warning signs before our eyes, resigning ourselves to a bad future because it doesn’t demand any sacrifice from our present is the weary fatalism of a man that’s given up. His assessment isn’t wrong, he’s just not representative of the kind of scientist that’s going to fix it.

“Something has been lost,” Tomorrowland director Brad Bird believes. “Pessimism has become the only acceptable way to view the future, and I disagree with that. I think there’s something self-fulfilling about it. If that’s what everybody collectively believes, then that’s what will come to be. It engenders passivity: If everybody feels like there’s no point, then they don’t do the myriad of things that could bring us a great future.”

Walt Disney once said, “If you can dream it, you can do it.” Tomorrowland‘s emotional call for dreamers from the diverse corners of the globe is the hope that can never be lost as we navigate a changing, tumultuous world, from dismal climate reports to devastating droughts that threaten food and water supply to perilous conflicts at all corners of our globe. Because ultimately, the precious commodity of innovation and a better tomorrow rests with the potential of this group. We go to the movies to dream about what is possible, to be inspired and entertained. Utilizing the lens of cinematic symbolism, this film begs us to engage our imaginations through science, technology and innovation. It is the epitome of everything Walt Disney stood for and made possible. It’s also a timely, germane message that should resonate to a world that still needs saving.

Oh, and the blink-and-you-miss-it quote posted on the entrance to the fictional Tomorrowland? “Imagination is more important than knowledge.” —Albert Einstein.

View the Tomorrowland trailer:

Tomorrowland goes into wide release on May 22, 2015.

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development. Follow us on Twitter and Facebook. Subscribe to our podcast on SoundCloud or iTunes.

For every friendly robot we see in science fiction such as Star Wars‘s C3PO, there are others with a more sinister reputation that you can find in films such as I, Robot. Indeed, most movie robots can be classified into a range of archetypes and purposes. Science boffins at Cambridge University have taken the unusual step of evaluating the exact risks of humanity suffering from a Terminator-style meltdown at the Cambridge Project for Existential Risk.

“Robots On the Run” is currently an unlikely scenario, so don’t stockpile rations and weapons in panic just yet. But with machine intelligence continually evolving, developing and even crossing thresholds of creativity and and language, what holds now might not in the future. Robotic technology is making huge advances in great part thanks to the efforts of Japanese scientists and Robot Wars. For the time being, the term AI (artificial intelligence) might sound like a Hollywood invention (the term was translated by Steven Spielberg in a landmark film, after all), but the science behind it is real and proliferating in terms of capability and application. Robots can now “learn” things through circuitry similar to the way humans pick up information. Nevertheless, some scientists believe that there are limits to the level of intelligence that robots will be able to achieve in the future. In a special ScriptPhD review, we examine the current state of artificial intelligence, and the possibilities that the future holds for this technology.

Is AI a false dawn?

While artificial intelligence has certainly delivered impressive advances in some respects, it has also not successfully implemented the kind of groundbreaking high-order human activity that some would have envisaged long ago. Replicating technology such as thought, conversation and reasoning in robots is extraordinarily complicated. Take, for example, teaching robots to talk. AI programming has enabled robots to hold rudimentary conversations together, but the conversation observed here is extremely simple and far from matching or surpassing even everyday human chit-chat. There have been other advances in AI, but these tend to be fairly singular in approach. In essence, it is possible to get AI machines to perform some of the tasks we humans can cope with, as witnessed by the robot “Watson” defeating humanity’s best and brightest at the quiz show Jeopardy!, but we are very far away from creating a complete robot that can manage humanity’s complex levels of multi-tasking.

Despite these modest advances to date, technology throughout history has often evolved in a hyperbolic pattern after a long, linear period of discovery and research. For example, as the Cambridge scientists pointed out, many people doubted the possibility of heavier-than-air flight. This has been achieved and improved many times over, even to supersonic speeds, since the Wright Brothers’ unprecedented world’s first successful airplane flight. In last year’s sci-fi epic Prometheus the android David is an engineered human designed to assist an exploratory ship’s crew in every way. David anticipates their desires, needs, yet also exhibits the ability to reason, share emotions and feel complex meta-awareness. Forward-reaching? Not possible now? Perhaps. But by 2050, computers controlling robot “brains” will be able to execute 100 trillion instructions per second, on par with human brain activity. How those robots order and utilize these trillions of thoughts, only time will tell!

If nature can engineer it, why can’t we?

The human brain is a marvelous feat of natural engineering. Making sense of this unique organ singularly differentiates the human species from all others requires a conglomeration of neuroscience, mathematics and physiology. MIT neuroscientist Sebastian Seung is attempting to do precisely that – reverse engineer the human brain in order to map out every neuron and connection therein, creating a road map to how we think and function. The feat, called the connectome, is likely to be accomplished by 2020, and is probably the first tentative step towards creating a machine that is more powerful than human brain. No supercomputer that can simulate the human brain exists yet. But researchers at the IBM cognitive computing project, backed by a $5 million grant from US military research arm DARPA, aim to engineer software simulations that will complement hardware chips modeled after how the human brain works. The research is already being implemented by DARPA into brain implants that have better control of artificial prosthetic limbs.

The plausibility that technology will catch up to millions of years of evolution in a few years’ time seems inevitable. But the question remains… what then? In a brilliant recent New York Times editorial, University of Cambridge philosopher Huw Price muses about the nature of human existentialism in an age of the singularity. “Indeed, it’s not really clear who “we” would be, in those circumstances. Would we be humans surviving (or not) in an environment in which superior machine intelligences had taken the reins, to speak? Would we be human intelligences somehow extended by nonbiological means? Would we be in some sense entirely posthuman (though thinking of ourselves perhaps as descendants of humans)?” Amidst the fears of what engineered beings, robotic or otherwise, would do to us, lies an even scarier question, most recently explored in Vincenzo Natali’s sci-fi horror epic Splice: what responsibility do we hold for what we did to them?

Is it already checkmate, AI?

Artificial intelligence computers have already beaten humans hands down in a number of computational metrics, perhaps most notably when the IBM chess computer Deep Blue outwitted then-world champion Gary Kasparov back in 1997, or the more recent aforementioned quiz show trouncing by deep learning QA machine Watson. There are many reasons behind these supercomputing landmarks, not the least of which is a much quicker capacity for calculations, along with not being subject to the vagaries of human error. Thus, from the narrow AI point of view, hyper-programmed robots are already well on their way, buoyed by hardware and computing advances and programming capacity. According to Moore’s law, the amount of computing power we can fit on a chip doubles every two years, an accurate estimation to date, despite skeptics who claim that the dynamics of Moore’s law will eventually reach a limit. Nevertheless, futurist Ray Kurtzweil predicts that computers’ role in our lives will expand far beyond tablets, phones and the Internet. Taking a page out of The Terminator, Kurtzweil believes that humans will eventually be implanted with computers (a sort of artificial intelligence chimera) for longer life and more extensive brain capacity. If the researchers developing artificial intelligence at Google X Labs have their say, this feat will arrive sooner rather than later.

There may be no I in robot, but that does not necessarily mean that advanced artificial beings would be altruistic, or even remotely friendly to their organic human counterparts. They do not (yet) have the emotions, free will and values that humans use to guide our decision-making. While it is unlikely that robots would necessarily be outright hostile to humans, it is possible that they would be indifferent to us, or even worse, think that we are a danger to ourselves and the planet and seek to either restrict our freedom or do away with humans entirely. At the very least, development and use of this technology will yield considerable novel ethical and moral quandaries.

It may be difficult to predict what the future of technology holds just yet, but in the meantime, humanity can be comforted by the knowledge that it will be a while before robots, or artificial intelligence of any kind, subsumes our existence.

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development. Follow us on Twitter and Facebook. Subscribe to our podcast on SoundCloud or iTunes.

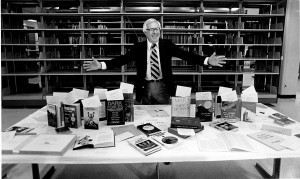

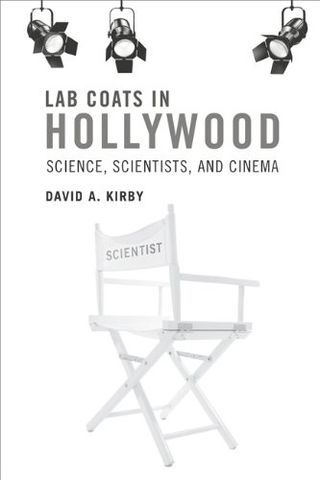

Read through any archive of science fiction movies, and you quickly realize that the merger of pop culture and science dates as far back as the dawn of cinema in the early 1920s. Even more surprising than the enduring prevalence of science in film is that the relationship between film directors, scribes and the science advisors that have influenced their works is equally as rich and timeless. Lab Coats in Hollywood: Science, Scientists, and Cinema (2011, MIT Press), one of the most in-depth books on the intersection of science and Hollywood to date, serves as the backdrop for recounting the history of science and technology in film, how it influenced real-world research and the scientists that contributed their ideas to improve the cinematic realism of science and scientists. For a full ScriptPhD.com review and in-depth extended discussion of science advising in the film industry, please click the “continue reading” cut.

Written by David A. Kirby, Lecturer in Science Communication Studies at the Centre for History of Science, Technology and Medicine at the University of Manchester, England, Lab Coats offers a surprising, detailed analysis of the symbiotic—if sometimes contentious—partnership between filmmakers and scientists. This includes the wide-ranging services science advisors can be asked to provide to members of a film’s production staff, how these ideas are subsequently incorporated into the film, and why the depiction of scientists in film carries such enormous real-world consequences. Thorough, detailed, and honest, Lab Coats in Hollywood is an exhaustive tome of the history of scientists’ impact on cinema and storytelling. It’s also an essential and realistic road map of the challenges that scientists, engineers and other technical advisors might face as they seriously pursue science advising to the film industry as a career.

The essential questions that Lab Coats in Hollywood addresses are these—is it worth it to hire a science advisor for a movie production? Is it worth it for the scientist to be an advisor? The book’s purposefully vague conclusion is that it depends solely on how the scientist can film’s storyline and visual effects. Kirby wisely writes with an objective tone here because the topic is open to a considerable amount of debate among the scientists and filmmakers profiled in the book. Sometimes a scientist is so key to a film’s development, he or she becomes an indispensible part of the day-to-day production. A good example of this is Jack Horner, paleontologist at the Museum of the Rockies in Bozeman, MT, and technical science advisor to Steven Spielberg in Jurassic Park and both of its sequels. Horner, who drew from his own research on the link between dinosaurs and birds for a more realistic depiction of the film’s contentious science, helped filmmakers construct visuals, write dialogue, character reactions, animal behaviors, and map out entire scenes. J. Marvin Herndon, a geophysicist at the Transdyne Corporation, approached the director of the disaster film The Core when he learned the plot was going to be based on his controversial hypothesis about a giant uranium ball in the center of the Earth. Herndon’s ideas were fully incorporated into the film’s plot, while Herndon rode the wave of publicity from the film to publish his research in a PNAS paper. The gold standard of science input, however, were Stanley Kubrik’s multiple science and engineering advisors for 2001: A Space Odyssey, discussed in much further detail below.

Kirby hypothesizes that sometimes, a film’s poor reception might have been avoided with a science advisor. He provides the example of the Arnold Schwarzenegger futuristic sci-fi bomb The Sixth Day, which contained a ludicrously implausible use of human cloning in its main plot. While the film may have been destined for failure, Kirby posits that it only could have benefited from proper script vetting by a scientist. By contrast, the 1998 action adventure thriller Armageddon came under heavy expert criticism for its basic assertion that an asteroid “the size of Texas” could go undetected until eighteen days before impact. Director Michael Bay patently refused to take the advice of his advisor, NASA researcher Ivan Bakey, and admitted he was sacrificing science for plot, but Armageddon went on to be a huge box office hit regardless. Quite often, the presence of a science advisor is helpful, albeit unnecessary. One of the book’s more amusing anecdotes is about Dustin Hoffman’s hyper-obsessive shadowing of a scientist for the making of the pandemic thriller Outbreak (great guide to the movie’s science can be found here). Hoffman was preparing to play a virologist and wanted to infuse realism in all of his character’s reactions. Hoffman kept asking the scientist to document reactions in mundane situations that we all encounter—a traffic jam, for example—only to come to the shocking conclusion that the scientist was a real person just like everyone else.

Most of the time, including scientists in the filmmaking process is at the discretion of the studios because of the one immutable decree reiterated throughout the book: the story is king. When a writer, producer or director hires a science consultant, their expertise is utilized solely to facilitate, improve or augment story elements for the purposes of entertaining the audience. Because of this, one of the most difficult adjustments a science consultant may face is a secondary status on-set even though they may be a superstar in their own field. Some of the other less glamorous aspects of film consulting include heavy negotiations with unionized writers for script or storyline changes, long working hours, a delicate balance between side consulting work and a day job, and most importantly, an inconsistent (sometimes nonexistent) payment structure per project. I was notably thrilled to see Kirby mention the pros and cons of programs such as the National Science Foundation’s Creative Science Studio (a collaboration with USC’s school of the Cinematic Arts) and the National Academy of Science’s Science and Entertainment Exchange, which both provide on-demand scientific expertise to the Hollywood filmmaking community in the hope of increasing and promoting the realism of scientific portrayal in film. While valuable commodities to science communication, both programs have had the unfortunate effect of acclimating Hollywood studios to expect high-level scientific consulting for free.

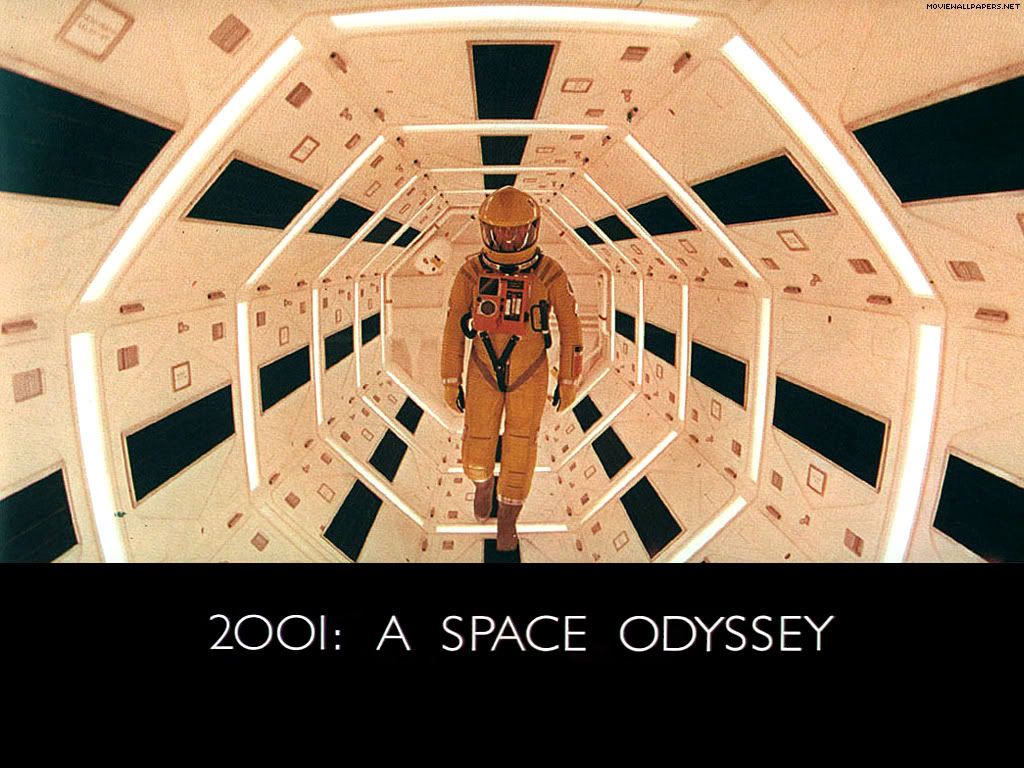

1968’s 2001: A Space Odyssey is widely considered by popular consensus to be the greatest sci-fi movie ever made, and certainly the most influential. As such, Kirby devotes an entire chapter to detailing the film’s production and integration of science. Director Stanley Kubrik took painstaking detail in scientific accuracy to explore complex ideas about the relationship between humanity and technology, hiring a range of advisors from anthropologists, aeronautical engineers, statisticians, and nuclear physicists for various stages of production. Statistician I. J. Good provided advice on supercomputers, aerospace Harry Lange provided production design, while NASA space scientist Frederick Ordway lent over three years of his time to develop the space technology used in the film. In doing so, Kubrik’s staff consulted with over sixty-five different private companies, government agencies, university groups and research institutions. So real was the space technology in 2001 that moon landing hoax supporters have claimed the real moon landing by United States astronauts, taking place in 1969, was taped on the same sets. Not every science-based film has used science input as meticulously or thoroughly since, but Kubrik’s influence on the film industry’s fascination with science and technology has been an undeniable legacy.

One of the real treats of Lab Coats in Hollywood is the exploration of the two-way relationship between scientists and filmmakers, and how film in turn influences the course of science, as we discuss in more detail below. Between film case studies, critiques and interviews with past science advisors are interstitial vignettes of ways scientists have shaped films we know and love. Even the animated feature Finding Nemo had an oceanography advisor to get the marine biology correct. The seminal moment of the most recent Star Trek installation was due to a piece of off-handed scientific advice from an astronomer. The cloning science of Jurassic Park, so thoroughly researched and pieced together by director Steven Spielberg and science advisor Jack Horner, was actually published in a top-notch journal days ahead of the movie’s premiere. Even in rare spots where the book drags a bit with highly technical analysis are cinematic backstories with details that readers will salivate over. (For example, there’s a very good reason all the kelp went missing from Finding Nemo between its cinematic and DVD releases.)

As the director of a creative scientific consulting company based in Los Angeles, one of the biggest questions I get asked on a regular basis is “What does a science advisor do, exactly?” Lab Coats in Hollywood does an excellent job of recounting stories and case studies of high-profile scientist consultants, all of whom contributed their creative talents to their respective films in different ways, what might be expected (and not expected) of scientists on set, and of giving different areas of expertise that are currently in demand in Hollywood. Kirby breaks down cinematic fact checking, the most frequent task scientists are hired to perform, into three areas within textbook science (known, proven facts that cannot be disputed, such as gravity): public science, something we all know and would think was ridiculous if filmmakers got wrong, expert science, facts that are known to specialists and scientific experts outside of the lay audience, and (most problematic) folk science, incorrect science that has nevertheless been accepted as true by the public. Filmmakers are most likely to alter or modify facts that they perceive as expert science to minimize repercussions at the box office.

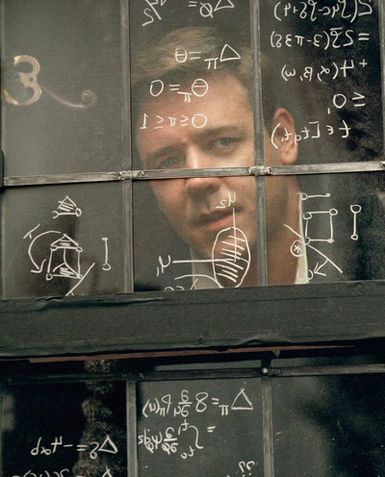

A science advisor is constantly navigating cinematic storytelling constraints and a filmmaker’s desire to utilize only the most visually appealing and interesting aspects of science (regardless of whether the context is always academically appropriate). Another broad area of high demand is in helping actors look and act like a real scientist on screen. Scientists have been hired to do everything from doctoring dialogue to add realism into an actor’s portrayal (the movie Contact and Jodie Foster’s depiction of Dr. Ellie Arroway is a good example of this), training actors in using equipment and pronouncing foreign-sounding jargon, replicating laboratory notebooks or chalkboard scribbles with the symbols and shorthand of science (such as in the mathematics film A Beautiful Mind), and to recreate the physical space of an authentic laboratory. Finally, the scientist’s expertise of the known is used to help construct plausible scenarios and storylines for the speculative, an area that requires the greatest degree of flexibility and compromise from the science advisor. Uncertainty, unexplored research and “what if” scenarios, the bane of every scientist’s existence, happen to be Hollywood’s favorite scenarios, because they allow the greatest creative freedom in storytelling and speculative conceptualization without being negated by a proven scientific impossibility. An entire chapter—the book’s finest—is devoted to two case studies, Deep Impact and The Hulk, where real science concepts (near-Earth asteroid impacts and genetic engineering, respectively) were researched and integrated into the stories that unfolded in the films. (Side note: if you are ever planning on being a science advisor read this section of the book very carefully).

In years past, consulting in films didn’t necessarily bring acclaim to scientists within their own research communities; indeed, Lab Coats recounts many instances where scientists were viewed as betraying science or undermining its seriousness with Hollywood frivolity, including many popular media figures such as Carl Sagan and Paul Ehrlich. Recently, however, consultants have come to be viewed as publicity investments both by studios that hire high-profile researchers for recognition value of their film’s science content and by institutes that benefit from branding and exposure. Science films from the last 10-15 years such as GATTACA, Outbreak, Armageddon, Contact, The Day After Tomorrow and a panoply of space-related flicks have attached big-name scientists as consultants (gene therapy pioneer French Anderson, epidemiologist David Morens, NASA director Ivan Bekey, SETI institute astronomers Seth Shostak and Jill Tartar and climatologist Michael Molitor, respectively). They also happened to revolve around the research salient to our modern era: genetic bioengineering, global infectious diseases, near-earth objects, global warming and (as always) exploring deep space. As such, a mutually beneficial marketing relationship has emerged between science advisors and studios that transcends the film itself resulting in funding and visibility to individual scientists, their research, and even institutes and research centers. The National Severe Storms Laboratory (NSSL) promoted themselves in two recent films, Twister and Dante’s Peak, using the films as a vehicle to promote their scientific work, to brand themselves as heroes underfunded by the government, and to temper public expectations about storm predictions. No institute has had a deeper relationship with Hollywood than NASA, extending back to the Star Trek television series, with intricate involvement and prominent logo display in the films Apollo 13, Armageddon, Mission to Mars, and Space Cowboys. Some critics have argued that this relationship played an integral role in helping NASA maintain a positive public profile after the devastating 1986 Challenger space shuttle disaster. The end result of the aforementioned promotion via cinematic integration can only benefit scientific innovation and public support.

Accurate and favorable portrayal of science content in modern cinema has an even bigger beneficiary than specific research institutes, and that is society itself. Fictional technology portrayed in film – termed a “diegetic prototype” – has often inspired or led directly to real-world application and development. Kirby offers the most impactful case of diegetic prototyping as the 1981 film Threshold, which portrayed the first successful implantation of a permanent artificial heart, a medical marvel that became reality only a year later. Robert Jarvik, inventor of the Jarvik-7 artificial heart used in the transplant, was also a key medical advisor for Threshold, and felt that his participation in the film could both facilitate technological realism and by doing so, help ease public fears about what was then considered a freak surgery, even engendering a ban in Great Britain. Of the many obstacles that expensive, ambitious, large-scale research faces, Kirby argues that skepticism or lack of enthusiasm from the public can be the most difficult to overcome, precisely because it feeds directly into essential political support that makes funding possible. A later example of film as an avenue for promotion of futuristic technology is Minority Report, set in the year 2054, and featuring realistic gestural interfacing technology and visual analytics software used to predict crime before it actually happens. Less than a decade later, technology and gadgets featured in the film have come to fruition in the form of multi-touch interfaces like the iPad and retina scanners, with others in development including insect robots (mimics of the film’s spider robots), facial recognition advertising billboards, crime prediction software and electronic paper. A much more recent example not featured in the book is the 2011 film Limitless, featuring a writer that is able to stimulate and access 100% of his brain at will by taking a nootropic drug. While the fictitious drug portrayed in the film is not yet a neurochemical reality, brain enhancement is a rising field of biomedical research, and may one day indeed yield a brain-boosting pill.

No other scientific feat has been a bigger beneficiary of diegetic prototyping than space travel, starting with 1929’s prophetic masterpiece Frau im Mond [Woman in the Moon], sponsored by the German Rocket Society and advised masterfully by Hermann Oberth, a pioneering German rocket research scientist. The first film to ever present the basics of rocket travel in cinema, and credited with the now-standard countdown to zero before launch in real life, Frau im Mond also featured a prototype of the liquid-fuel rocket and inspired a generation of physicists to contribute to the eventual realization of space travel. Destination Moon, a 1950 American sci-fi film about a privately financed trip to the Moon, was the first film produced in the United States to deal realistically with the prospect of space travel by utilizing the technical and screenplay input of notable science fiction author Robert A. Heinlein. Released seven years before the start of the USSR Sputnik program, Destination Moon set off a wave of iconic space films and television shows such as When Worlds Collide, Red Planet Mars, Conquest of Space and Star Trek in the midst of the 1950s and 1960s Cold War “space race” between the United States and Russia. What theoretical scientific feat will propel the next diegetic prototype? A mission to Mars? Space colonization? Anti-aging research? Advanced stem cell research? Time will only tell.

Ultimately, readers will enjoy Lab Coats in Hollywood for its engaging writing style, detailed exploration of the history of science in film and most of all, valuable advice from fellow scientists who transitioned from the lab to consulting on a movie set. Whether you are a sci-fi film buff or a research scientist aspiring to be a Hollywood consultant, you will find some aspect of this book fascinating. Especially given the rapid proliferation of science and technology content in movies (even those outside of the traditional sci-fi genre), and the input from the scientific community that it will surely necessitate, knowing the benefits and pitfalls of this increasingly in-demand career choice is as important as its significance in ensuring accurate portrayal of scientists to the general public.

~*ScriptPhD*~

***************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development.

Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

]]>

I was recently watching Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps, the sequel to the Oscar-winning 1987 financial cautionary tale. In the middle of a movie that had nothing to do with science, the lead character started explaining the financial investment potential of a national research facility loosely based on the ultra-exclusive National Ignition Facility in Livermore, CA (which ScriptPhD.com was fortunate to visit and profile recently). The film did such an impressive job of explaining the laser technology being used in real life to harness endless quantities of energy from a molecular fusion reaction that it could have easily been lifted from a physics textbook. Translating, explaining and visually presenting complex science on film is not an easy task. It got us to thinking about some of the greatest science and technology moments of all time in film.

In no particular order, with the help of our readers and fans, here are ScriptPhD.com’s choices for the Top 10 gamechangers of science and/or technology cinematic content that was either revolutionary for its time, was smartly conceived and cinematically executed, or has bared relevance to later research advances.

Gattaca

A trend-setter in genomics and bioinformatics, long before they were scientific staples, 1997 sci-fi masterpiece Gattaca has some of the most thoughtful, smart, introspective science of any film. To realize his life-long dream of space travel, genetically inferior Vincent Freeman (Ethan Hawke) assumes the DNA identity of Jerome Morrow (Jude Law), but becomes a suspect in the murder of the space program director. Not only is this the first (and only) movie to have a clever title composed solely of DNA sequence letters (G, A, T and C are the nucleotide bases that make up DNA), it was declared by molecular biologist Lee M. Silver as “a film that all geneticists should see if for no other reason than to understand the perception of our trade held by so many of the public-at-large.” In 1997, we were still 6 years away from the completion of the Human Genome Project. Post that feat of modern biotechnology, the ability to obtain ‘personal genomics’ disease profiles has led bioethicists to question who is to be entrusted with interpreting personal DNA information, and the United States Congress to pass the Genetic Information Non-Discrimination Act. Could we find ourselves in a world that judges the genetically perfect as ‘valids’ and anyone with minor flaws (and what constitutes a flaw?) as ‘invalids’? The eugenic determinism in Gattaca certainly portrays an eerily realistic portrait of such a world.

Contact

Voted on by several of our Facebook and Twitter fans (in complete agreement with us), Contact (based on the book by the most important astronomer of our time, Carl Sagan) is an astonishingly smart movie about the true meaning of human existence, explored through the first human contact with intelligent extraterrestrials. Rarely ambitious and quietly thoughtful science fiction for a big-budget movie, Contact is also one of the best explorations of the divide between science and religion. Bonus points for Jodie Foster’s eloquent and dedicated portrayal of what a real scientist is like.

A Beautiful Mind

It’s not often that cinema even touches mathematics or physics with depth and significance. It’s even rarer to see complex mathematics at the center of a poignant plot. 2001 Academy Award winning drama A Beautiful Mind was inherently not a film about mathematics, but rather one man’s quest to overcome a debilitating mental illness to achieve greatness. Nevertheless, the presentation of abstract mathematics, notably the Nash equilibrium that won John Nash the Nobel Prize in Economics in 1994, is not only difficult to do in film, but is done extraordinarily well by director Ron Howard. For anyone that has studied high-level math, or known a math professor, this film gives a picture-perfect portrayal, and possibly inspired a new generation of aspiring mathematicians.

2001: A Space Odyssey

2001: A Space Odyssey is the greatest sci-fi film ever made. Period. Kubrik’s classic introduces an ahead-of-its-time exploration of human evolution, artificial intelligence, technology, extraterrestrial life and the place of humanity in the greater context of the universe. Although definitively esoteric in its content, individual elements could be lifted straight from a science textbook. The portrayal of an ape learning to use a bone as a tool and weapon. Missions to explore outer space, including depictions of alien life, spacecraft and computers that are so realistic, they were built based on consultations with NASA and Carl Sagan. The Heuristic ALgorithmic computer (HAL) that runs the ship’s operations is depicted as possessing as much, if not more intelligence than human beings, an incredibly prescient feat for a film made in 1968.

The Day The Earth Stood Still

The Day the Earth Stood Still (we speak of the original, and not its insipid 2008 remake) is a seminal film in the development of the big-budget studio sci-fi epics. Given its age (the original came out in 1951), it still stands the test of time as a warning about the dangers of nuclear power. Well-made, sophisticated and not campy, TDTESS is one of the best cinematic emblems of the scientific anxieties and realities of the Cold War and nuclear era. It is usually a staple of Top Sci-Fi lists.

Jurassic Park

Jurassic Park, originally released in 1993, set one of the most important landmarks for modern science in film—the incorporation of DNA cloning as a significant plot element three full years BEFORE the birth of Dolly, the cloned sheep. Even more important than the fact that, although highly improbable, the science of Jurassic Park was plausible, is the idea that it was presented in an intelligent, casual and meaningful way, with the assumption (and expectation) that the audience would grasp the science well enough not to distract from the rest of the film. Furthermore, the basic plot of the film (and the book on which it was based) act as a cautionary tale about the dangers of unchecked scientific experimentation, and the havoc it can wreak when placed in the wrong hands. With the completion of the Human Genome Project in 2003, and the ability to sequence an organism’s genome in a day, bioethical questions about how personal genomics and the resurgent gene therapy are used are perfectly valid. Jurassic Park set a new standard for how modern science would be incorporated into movies.

Terminator 1 and Terminator 2

The Terminator?! Sounds campy, I know. We associate these adventure blockbuster films more with action, explosions and the rise of Arnold Schwarzenegger. Not game-changing science. Think again. The cyborg technology presented in these 1984/1991 action adventures was not only far ahead of its time scientifically, but smart, conceptual, and has really stood the test of time. Countless engineers and aspiring scientists must have been inspired by the artificially intelligent robots when the film first premiered. Today, with robotics technology enabling everything from roomba vacuum cleaners to automated science research, many engineers postulate that the day could even come that humanoid robots could someday fight our wars. Earlier this year, scientists at the German Aerospace Center even created the first ‘Terminator’-like super strong robot hand!

Apollo 13

Space. The final frontier. At least in the heart of the movies. Far beyond the sci-fi genre, space travel, extraterrestrial life, and NASA missions remain a potent fascination in the cinematic world. For its feat as one of the most factually-correct space travel films ever made, with pinpoint portrayal of a monumentally significant event in the history of American science and technology, Apollo 13 enthusiastically lands on our list. Ron Howard’s almost-obsessive dedication to accuracy in detail included zero gravity flights for the actors (in addition to attending US Space Camp in Huntsville, AL), studying the mission control tapes, and an exact redesign of the layout of the Apollo spacecraft controls. Not only does the story inspire the spirit of adventure and innovation, it is 100% true.

The Andromeda Strain

For a film made in 1971, The Andromeda Strain (based on Michael Crichton’s novel by the same name) is a remarkably modern and prescient movie that has had a lot of staying power. The first really significant bio thriller film made, Andromeda’s killer viruses, transmissibility, and global infections have become de rigeur in our modern world. In the film, a team of scientists investigate a deadly organism of extraterrestrial origin that causes rapid, deadly blood clotting—perhaps an unintentional foreboding of Ebola and other hemorrhagic viruses. While the idea of a terrifying pandemic or biological emergency has certainly been replicated in many films such as Outbreak and 28 Days Later, no film has done a better job of capturing not just the sheer terror of an unknown outbreak, but the science behind containment, including government organization, the team of scientists working in a Biosafety Level-4 laboratory, and the fact that the story doesn’t overshadow the focus on the research and lab work. (Incidentally, as far-fetched as Crichton’s plot seemed to be at the time, recent research has shown that Earthly microbes traveling with US astronauts gained strength and virulence in space!)

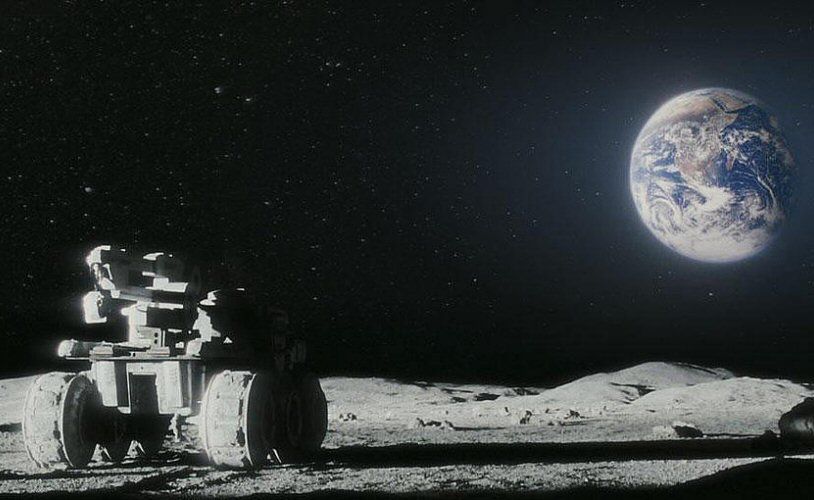

Moon

One of the most recent films to crack our Top 10 list, 2009’s debut gem from sci-fi director Duncan Jones failed to amass an audience commensurate to its brilliance and modern scientific relevance. A sweeping, gorgeous epic in the shadow of (and certainly inspirited by) 2001: A Space Odyssey, Moon (ScriptPhD.com review) tells the story of Astronaut Sam Bell (Sam Rockwell), who is at the tail-end of a three-year solo stint on the Moon, mining for Helium-3 resources to send back to an energy-depleted Earth. As the sole employee of his lunar station, Bell works alongside an intelligent computer named GERTY (Hal’s third generation cousin), but on the heels of his return to Earth, uncovers an insidious plot by the company he works for to keep him there forever. There are so many scientific and technology themes that made this an obvious choice for our list. Moon exploration and human colonization has been a hot topic for at least the last 15 years, with a recent discovery that the Moon may have as much water as the Earth sure to fuel possible NASA exploration and additional Moon missions. The ethical morass of a greedy company with technology capabilities cloning an employee is not only done brilliantly, but evokes a realistic, chilling possibility in our evolving scientific landscape. Finally, Sam’s relationship with GERTY (voiced by Kevin Spacey), who ultimately transcends his robotic limitations to exercise free will in helping Sam escape the pod, is especially poignant as technology becomes a more intimate part of human life and literally changes our neurological makeup.

~*ScriptPhD*~

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development.

Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

]]>

In his State of the Union speech in January, US President Barack Obama proclaimed that “we need to teach our kids that it’s not just the winner of the Super Bowl who deserves to be celebrated, but the winner of the science fair.” A noble (and correct) assessment, to be sure, but one mired in numerous educational and cultural obstacles. For one thing, science fairs themselves are at a perilous crossroads. A New York Times report issued in February stated that not only is participation in science fairs among high school kids falling, but that the kind of creativity and independent exploration that these competitions necessitate is impossible under current rigid test-driven educational guidelines for teaching mathematics and science. Indeed, an interesting recent Newsweek article on “The Creativity Crisis” conveyed research studies showing that for the first time, American creativity is declining. How appropriate, then, that this April (national math education month) brings the culmination of the Google World Science Fair, the first ever competition of its kind transpiring online and open to lab rats from all over the globe. ScriptPhD.com discusses why this could be a game-changer for the next generation of young scientists, under the “continue reading” cut.

One of the most chilling chapters in Thomas Friedman’s brilliant 2005 book “The World is Flat” discusses the ramifications of the globalization of science, and how quickly America is getting left behind. In addition to global “flatteners” (connectors) such as the internet, outsourcing, and yes, even access to free information via Google, Friedman details how hard third-world nations such as India and China work to attain supreme educations in math and science. On the one hand, they are producing more raw talent than ever, which often (due to lack of job opportunities and world-class facilities) finds its way into American (and Western) laboratories and corporations. On the other hand, it leaves American students and scientists ill-prepared to compete in a globalized economy based on information rather than raw production. (See Tom’s talk about global flattening at MIT here.) China will surpass the United States in patent filings by scientists by 2020. They are set to overtake the US in published research output even faster – in 2 years! Disturbingly, US teens ranked 25th out of 34 countries in math and science in the most recent world rankings, prompting President Obama to direct $250 million dollars towards math and science education. How that education is conveyed in classrooms is a subject of quite ardent debate.

Clearly, science education, in its current incarnation, is not working successfully. Unorthodox curricula have been proposed by numerous academic institutions, and even implemented with success in some countries. Furthermore, the idea of iconoclasts and self-taught geniuses, left alone to ferment their creativity, is not new. Albert Einstein famously clashed with authorities in primary school (which he barely finished), noting that “the spirit of creativity and learning were lost in strict rote learning.” In 2009, self-taught college dropout Erik Anderson proposed a major new theory on the structure of spiral galaxies and published it in one of the world’s most prestigious journals. (See ScriptPhD.com’s excellent post on whether creativity can really be measured in the lab.) Enter the Google World Science Fair. Capitalizing on the web and social media-driven knowledge of the current generation, they aim to not only expand on traditional well-known science competitions like Intel and Siemens, but to catapult them into the modern Internet era. Concomitantly, and even more importantly, as the fair’s organizers relayed over the weekend to the New York Times, they wish to improve science and math education in America incorporating a brand that many kids are already familiar with and use with ease. Why not infuse the excitement of a Google search into the staid, antiquated methodologies afflicting much of math and science curricula today? The impacts of science and independent experimentation are wide-reaching and powerful. During a gathering of scientists, students and judges on the day of the science fair announcement at Google headquarters, African self-taught scientist William Kamkwamba shared how from a library book, he was able to build a wind mill that powered his large family’s house, brought water to his impoverished village, but then taught other villagers to build wind mills, and by proxy, improved schools and living conditions. Who knows how many of this year’s global entrants will make such sizable contributions to their communities, or even, as they’re encouraged to do, solve global-scale afflictions?

Beyond the originality factor, he Google competition is important in several ways. It’s virtual and literally open to anyone in the world so long as they are a student between the ages of 13-18, thereby negating the most obvious roadblock to participation in many science competitions: location and affordability. (Though studies argue that internet access is still an overwhelming factor in economic and social equality, which is a not insignificant hurdle for aspiring third world participants.) Secondly, the competition is being judged on a passion for science and ideas, especially those relevant to the world today. In an age when we’re trying to ameliorate diseases, epidemics, the effects of global warming and violently changing weather patterns, urban sprawl and overpopulation, along with an ever-frustrating lack of access to water, food and sanitation by the poor, a few extra ideas and approaches can’t hurt. After all, a 15-year-old Louis Braille invented a system of reading for the blind, 18-year-old Alexander Graham Bell sketched rough ideas for what would turn into the telephone, 14-year-old Philo T. Farnsworth invented the television, and the modern microscope that many entrants will likely use in their experiments was invented by a 16-year-old Anton van Leeuwenhoek! (See more here.)

In the same spirit of hip novelty and digital cleverness that they’ve infused into the age-old science fair, Google hired the team from Los Angeles-based Synn Labs, the same team behind the viral OK Go music video, to create a thirty-second Rube Goldberg-themed video promoting the science fair. It is, perhaps, the highlight of the competition itself! Take a look:

The submission deadline for the 2011 online global science fair is today, April 4, 2011. All information about submission, judging, prizes, and blogs about entries can be found on the Google Global Science Fair homepage. The site also offers resources for teachers and educators looking to gain ways to bring the essence of Google’s science fair into their classrooms. You can also track all projects, as well as interact and exchange ideas with other science buffs, on their Facebook fan page and Twitter page.

ScriptPhD.com encourages all of our readers, clients, and fans who either submitted entries by the deadline, had their kids enter, or know someone who entered the competition to come back and tell us about the experience on our Facebook page. We’d love to hear about it! We wholeheartedly support programs that promote science and innovation, especially applicable to mitigating global social and technological obstacles. Our consulting company mantra is that great creative enterprises are fueled by great ideas. So, too, are science and technology. As such, we applaud Google for reinventing (and virtualizing) science outreach to encourage ideas and transform an entire generation of scientists, regardless of location, education or perceived ability. And if you’re bummed that you missed out on this year’s competition, think of it this way: you have plenty of time to prepare for 2012!

This post was sponsored by Unruly Media.

~*ScriptPhD*~

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development.

Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

]]>

Battlestar Galactica is one of the defining, genre-changing science fiction shows of its, or perhaps any, time. The remake of the 1970s cult classic was sexy, sophisticated, and set a new standard for the science fiction shows and movies that will follow in its path. In addition to exploring staple concepts such as life, survival, politics and war, BSG reawakened its audience to science and its role in moral, ethical, and daily impact in our lives, especially given the technologically-driven era that we live in. “Writers were not allowed to jettison science for the sake of the story,” declares co-executive producer Jane Espenson in her foreword to the book. “Other than in specific instances of intentionally inexplicable phenomena, science was respected.” In an artful afterword, Richard Hatch (the original Apollo and Tom Zarek in the new series) concurs. “BSG used science not as a veneer, but as a key thematic component for driving many of the character stories… which is the art of science fiction.” The sustained use of complex, correct science as a plot element to the degree that was done in Battlestar Galactica is also a hallmark first. This is the topic of the new book The Science of Battlestar Galactica, newly released from Wiley Books, and written by Kevin R. Grazier, the very science advisor who consulted with the BSG writing staff on all things science, with a contribution from Wired writer Patrick DiJusto. Now, for the first time, everyone from casual fans to astrophysicists can gain insight into the research used to construct major stories and technology of the show—and learn some very cool science along the way. Our review of The Science of Battlestar Galactica (and our 100th blog post!) under the “continue reading” cut.

What is life? Seriously. I’m not asking one of those hypothetical existential questions that end up discussed ad nauseum in a dorm room at 3 AM. I’m asking the central question that Battlestar Galactica, and much of science fiction, is based around. The shortest section of The Science of Battlestar Galactica, “Life Began Out Here,” is its most poignant. No matter the conflict, subplot or theme explored on BSG, they ultimately reverted back to the idea of what constituted a living being, and what rights, if any, those beings possessed. It all boils down to cylons. What are they made of? How do their brains (potentially) work? How much information can they contain, and how is it processed from one dead cylon to its next incarnation? How could a cylon and a human mate successfully, and is their offspring (Hera Agathon) the Mitochondrial Eve of that society? How did they evolve? What is the biological difference between raiders, centurions, and humanoid cylons? Who can forget the ew gross factor of Boomer plugging her arm into the cylon computer system, but how could she do that, especially when she was made to act, feel and think as a human being? A brief, smart discussion on spontaneous evolution and basic biology gives way to a thoughtful evocation of our own efforts with artificial intelligence, and the responsibilities that it engenders. Take a look at the website of the MIT iGem Program, an annual competition to design biological systems that will operate in living cells from standard toolkits. Do some of their creations, including bacteria that eat industrial pollutants and treat lactose intolerance, constitute life, and are our own Cybernetic Life Nodes not too far away? The section ends in a fascinating debate over who we are more akin to—the humans of the Battlestar universe (as is widely assumed) or cylons. The answer would surprise you.

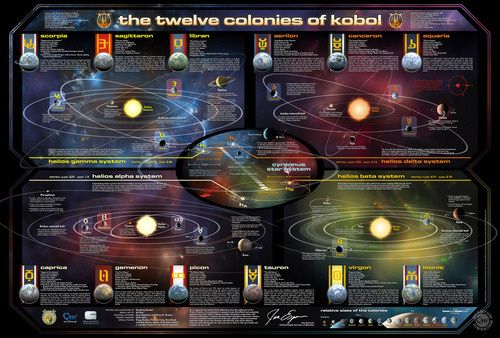

The middle of The Science of Battlestar Galactica, composed of “The Physics of Battlestar Galactica” and “The Twelve Colonies and The Rest of Space” reads largely like my college physics textbook, only with far cooler sample problems. If Apollo and Starbuck both launch their vipers at the same time and Starbuck coasts past Apollo, according to special relativity, who is moving? In perhaps the greatest implementation of Einstein’s famous theory in science fiction, special relativity explains how Starbuck could explain that she wasn’t a Cylon when she returned unharmed from the dead, and why her viper looked brand new. A special look at radiation particularly interested me, with a chemistry background, as it thoroughly delved into the chemistry and physics of radiation, heat-seeking missile weapons, DNA damage, and the power of nuclear weapons, both with fictional examples (the destruction of Caprica) and real (Japan and Chernobyl). The chapters on relativity (E=mc2) and the Lorentz Contraction reminded me of a seminar on dark energy that we covered at the Hollywood Laserium presented a year ago by Dr. Charles Baltay (NOT Baltar!), the man who was responsible for Pluto losing its planetary status. At the time, a lot of the concepts seemed a bit esoteric, but having read this book, are now elementary. Did you know, for example, that a supernova explosion is so powerful, it can briefly cause iron and other atoms remaining in the star to fuse into every naturally occurring element in the periodic table? Nifty, eh? Astronomy buffs, amateur and experienced, will enjoy the section on space, with a preamble on the formation of our galaxy and star systems to the 12 different planets of the Colonies, and how that many habitable planets could all be packed into such a dense area (see companion map below).

With perfect timing for the publication of The Science of BSG, Kevin R. Grazier and co-executive producer Jane Espenson have teamed up to create a plausible astronomy map of the 12 colonies of Battlestar Galactica. Find a larger, interactive version here.

One of the more fun aspects to watching BSG was the cornucopia of weapons, toys, and other electronics used by both humans and Cylons, a subject explored in the most meaty section of the whole book, “Battlestar Tech.” This includes a discussion of propulsion and how the Galactica’s jump drive might work, artificial gravity, a great chapter on the vipers and raptors as effective weapons, and positing how it is that Six was able to infiltrate the colonial computer infrastructure… besides the obvious, that is. I really enjoyed learning about Faraday cages, tachyon particles, brane cosmology, and what a back door is in computer programming, terms you can bet I will be throwing out casually at my next hoity-toity dinner party. The next time you rewatch an episode, and hear Mr. Gaeta utter a directive such as “We have a Cylon raider, CBDR, bearing 123 carom 45,” not only will you know exactly what he’s saying relative to the cartesian coordinates of the BSG space universe, but how this information is used to operate the complicated three-dimensional space system that the pilots have to operate in. Finally, critics such as myself of the dilapidated corded phones used aboard the Galactica will be interested to find out why they may have actually been a good idea in protecting the fleet from Cylon detection.

The ultimate selling point of this book is its ability to present material that will appeal to all fractions of a very diverse audience. The writing style is fluid, clever, informative and appropriately humorous in the way one would expect of a geeky sci-fi book (highlighted by a chapter on Cylon composition and detection thereof by Dr. Baltar written in dialogue format between an omniscient scientist and a smart-aleck fanboy). In fact, the co-authors merge their styles well enough so as to imagine that only one person wrote the book. Part textbook, part entertainment, part series companion, The Science of Battlestar Galactica is concomitantly smart, complicated, approachable and difficult—it does not surprise us one bit that in the couple of short months since its wide release, talk of numerous literary awards has already been circling. In between lessons on basic biology, astrophysics, energy and basic engineering are sprinkled delightful vignettes of actual on-set problem solving involving science. My favorites included plausible ways Cylons could download their information as they’re reborn (get ready for some serious computer-speak here!), an excellent explanation of Dr. Baltar’s mysterious Cylon detector, radiation and the difference between uninhabitable ‘dead Earth’ and barely habitable New Caprica, and the revelation by Dr. Grazier of how he had to—in a frantic period of 24 sleepless hours—construct a theory as to how the FTL drive works for an episode-specific reason. Much like the show it is based on, this book asks as many questions as it answers, most notably on social parables within our own world. Are we on our way to building Cylon artificial intelligence? Could our computer infrastructure ever get compromised like the ones on Caprica? Would we ever be able to travel to parallel universes, and what would be the implications of life forms besides our own? How might they even detect our presence?

Read our in-depth interview with Kevin R. Grazier here

Join our our Facebook fan page for a special giveaway commemorating the release of The Science of Battlestar Galactica and our 100th blog post. Now if you’ll excuse me, having read and absorbed this illuminating volume, I have been inspired to go and watch the entire series from start to finish all over again!

~*ScriptPhD*~

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development.

Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

]]>