In 2011, a cognitive supercomputing system developed at IBM named “Watson” was pitted against, and subsequently defeated, two of the most successful Jeopardy! game-show contestants of all time. A project five years in the making, Watson was initially developed as a “Grand Challenge” successor to Deep Blue, the machine that beat Gary Kasparov at chess, and was a prototype for DeepQA, a question/answer natural language analysis architecture. Since his Jeopardy! triumph, however, Watson has been successfully applied towards improving health care, oncology, business applications and soon enough… even education. At the same time that IBM has been expanding Watson’s cognitive computing abilities, they’ve also been brilliantly marketing him to the general public through a series of traditional and interactive ads.

As part of our ongoing “Selling Science Smartly” series, we analyze the Watson campaign in more depth and feature an exclusive and insightful podcast conversation with the IBM marketing team behind it.

Campaign: Watson

Agency: IBM/Ogilvy&Mather

Industry: Cognitive computing/information technology

Quick thought experiment. Name at least a couple of technology advertising campaigns (not including Apple) that have been so memorable and clever, they either compelled you to buy a product or piqued your curiosity to learn more about it. Chances are, you can’t. For one thing, outside of computers and gadgets, “big picture” technologies like cloud computing, artificial intelligence and artificial neural networks have still not become fully mainstream. For another, like many high-end sophisticated science applications, it is difficult to communicate such abstract applications in bite-size pieces. IBM’s recent Watson campaign, centered around its powerful cognitive question/answer (QA) computing device, defies conventional tech branding. It’s instantaneously attention-getting. It features Watson’s attributes by incorporating one of the hallmark rules of film-making/screenwriting: show, don’t tell. Most importantly, humans are the centerpiece of each commercial/spot, which is an important antidote to Hollywood-induced fears of robotic takeover and a more realistic depiction of how we will really subsume AI into our existence through small steps.

Here is Watson summarizing his seemingly endless array of capabilities for integration of deep learning:

Here is Watson explaining his capacity for improving digital health and diagnostics in medicine to an adorable young patient:

Recently, Watson displayed his technological versatility in an interactive campaign where he helped design a supermodel’s “Cognitive Dress.” The dress was equipped with lighting to monitor real-time social media reactions and represents an example of augmenting the creative process with technology in the future.

Why It’s Good Science Advertising

Whether he’s enjoying a one-on-one conversation with virtually any human, designing dresses or helping people cook gourmet meals, Watson comes across as versatile, approachable and interactive. Soon, Watson will even produce meta-advertising, in the form of cognitive marketing — enabling consumers to have remote brand-related conversations with Watson Ads suited to their individual needs and questions about a particular product. As illustrated in the video below, the Watson campaign, like the technology itself, represents a total commitment to brand awareness, IBM’s core mission and the eventual potential of the cognitive technology device. And, it’s memorable!

Why It Works

With a cognitive machine as powerful and versatile as Watson, brand messaging presents two major challenges: succinctly communicating the complex framework of solutions for consumers, businesses and institutions, and doing so in an emotionally engaging manner. Watson succeeds on both accounts. He describes his capabilities from a first-person perspective, not through omniscient narration. He functions through interlocution, which lends an intimacy to the commercials — any one of us might find ourselves interacting with Watson and requesting his help. He is fun and funny; brilliant yet adorably inept in human slang; cheeky yet serious; always helpful, curious and collaborative. In essence, Watson has been branded as an anthropomorphic companion instead of a sterile robot. 21st Century technology will inevitably be personal, inclusive and integrated into our lives. The Watson campaign feels like the realistic unveiling of the cognitive computing era. Take a look at Watson’s conversation with Ridley Scott about artificial intelligence, as portrayed in Hollywood (referenced in our podcast below):

What Other Science Campaigns Can Learn From This One

Creative risk-taking is essential for successfully marketing sophisticated technology, not just in the content itself, but in how it is crafted. In the immediate predecessor to the Watson campaign, a series of spots entitled “Made With IBM” traveled across three continents to share short, documentary-like stories about cross-applications of a panoply of IBM technology and its relevance in today’s connected world. Accordingly, the aggregate Watson ads and interactive spots present an engaged, personalized look at how cognitive computing will facilitate faster, more improved and easier tasks in all areas of human life in the future while making an immediate impact in several industries right now. Indeed, IBM’s commitment to incorporating storytelling across all of its content extends to the unusual move of hiring screenwriters to join its marketing team. IBM also partnered with the TED Institute for multi-year thought leadership symposium where critical ideas related to technology and data-driven computing, along with the ways they could change the world, were shared by leading experts. In the process, this multi-platform approach not only taps into the next generation of consumers, but slowly assuages understandable reservations about artificial intelligence.

To help gain insight into the creative development and thought process behind the Watson campaign, as well as the greater context of using didactic advertising and thought leadership to inform about complex technology, ScriptPhD.com was joined for a conversation with IBM’s Vice President of Branded Content and Global Creative Ann Rubin and Watson Chief Marketing Officer Stephen Gold. Listen to our podcast below:

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development. Follow us on Twitter and Facebook. Subscribe to our podcast on SoundCloud or iTunes.

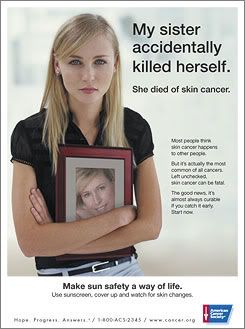

Earlier this year, the Susan G. Komen Foundation made headlines around the world after their politically-charged decision to cut funding for breast cancer screening at Planned Parenthood caused outrage and negatively impacted donations. Despite reversing the decision and apologizing, many people in the health care and fund raising community feel that the aftermath of the controversy still dogs the foundation. Indeed, Advertising Age literally referred to it as a PR crisis. If all of this sounds more like spin for a brand rather than a charity working towards the cure of a devastating illness, it’s not far from the truth. Susan G. Komen For the Cure, Avon Walk For Breast Cancer and the Revlon Run/Walk For Women represent a triumvirate hegemony in the “pink ribbon” fundraising domain. Over time, their initial breast cancer awareness movement (and everything the pink ribbon stood for symbolically) has moved from activism to pure consumerism. The new documentary Pink Ribbons, Inc. deftly and devastatingly examines the rise of corporate culture in breast cancer fundraising. Who is really profiting from these pink ribbon campaigns, brands or people with the disease? How has the positional messaging of these “pink ribbon” events impacted the women who are actually facing the illness? And finally, has motivation for profit driven the very same companies whose products cause cancer to benefit from the disease? ScriptPhD.com’s Selling Science Smartly advertising series continues with a review of Pink Ribbons, Inc..

“We used to march in the streets. Now you’re supposed to run for a cure, or walk for a cure, or jump for a cure, or whatever it is,” states Barbara Ehrenreich, breast cancer survivor and author of Welcome to Cancerland, in the opening minutes of the documentary Pink Ribbons, Inc. Directed by Canadian filmmaker Lea Pool and based on the book Pink Ribbons, Inc.: Breast Cancer and the Politics of Philosophy by Samantha King, the documentary features in-depth interviews with leading authors, experts, activists and medical professionals. It also includes an important look at the leading players in breast cancer fundraising and marketing. The production crew filmed a number of prominent fundraising events across North America, using the upbeat festivities (where some didn’t even visibly show the word ‘cancer’) as the backdrop for exploring the “pinkwashing” of breast cancer through marketing, advertising and slick gimmicks. At the same time, showcasing well-meaning, enthusiastic walkers, runners and fundraisers is a double-edged sword and was handled with the appropriate sensitivity by the filmmakers. Pool wanted to “make sure we showed the difference between the participants, and their courage and will to do something positive, and the businesses that use these events to promote their products to make money.”

Often lost amidst the pomp and circumstance of these bright pink feel-good galas is that the origins of the pink ribbon are quite inauspicious. The original pink ribbon wasn’t even pink. It was a salmon-colored cloth ribbon made by breast cancer activist Charlotte Haley as part of a grass roots organization she called Peach Corps. From a kitchen counter mail-in operation, Haley’s vision grew to hundreds of thousands of supporters, so much so that it caught the attention of Estee Lauder founder Evelyn Lauder. The company wanted to buy the peach ribbon from Haley, who refused, so they simply rebranded breast cancer to a comforting, reassuring, non-threatening color: bright pink. And before our very eyes, a stroke of marketing genius was born.

As the pink ribbon movement took hold of the fundraising community, the money started to spill over into mainstream advertising, adorning everything from the food we eat to the clothes we wear, all under the auspices of philanthropy. In theory, people should feel great about buying products that return some of their profits for such a great cause. In practice, many of these campaigns simply throw a bright pink cloak over false, if not cynical, advertising. Take Yoplait’s yearly “Save Lids to Save Lives” campaign:

For every lid you save from a Yoplait yogurt (and mail in, using a $0.44 stamp, mind you!), they will donate 10 cents to breast cancer research. If you ate three yogurts per day for fourth months, you will have raised a grand total of $36 for breast cancer research, but spent more on stamps and in environmental shipping waste. Not as impressive when you break it down, eh?

A recent American Express campaign called “Every Dollar Counts” pledged that every purchase during a four month period would incur a one cent donation to breast cancer research. Unfortunately, they never quantified donations commensurate to spending, so that meant whether you charged a pack of gum or a big screen TV to your AmEx, they would donate a penny. The breast cancer community was so outraged by this hubris, they staged a successful campaign to rescind the ads. The fact is, the above examples demonstrate that pink ribbons have become an industry, with demographics and talking points, just like everything else. Pinkwashing campaigns tend to target middle class, ultra-feminine white women. Why? Because they are typical targets that move the products these industries are trying to sell. Take the NFL’s recent pink screening campaign. Well-meaning or not, it came amidst a series of crimes and violence by NFL players, some of which was domestic in nature. One can imagine that players adorned in hot pink gear would have been a smart way to mollify its rather impressive female fanbase.

As Ehrenreich states in the documentary, the collective effect of this marketing has been to soften breast cancer into a pretty, pink and feminine disease. Nothing too scary, nothing too controversial. Just enough to keep raising money that goes… somewhere. Take a look at the recent chipper television campaign for the Breast Cancer Centre of Australia:

While some of the breast cancer-related branding and pink sponsorships mislead through good intentions, others are a dangerous bold-faced lie. Some of the very companies that sponsor fundraising events and make money off of pink revenue either make deleterious products linked to cancer or stand to profit from treatment of it. Revlon, sponsors of the Run/Walk for Women, are manufacturers of many cosmetics (searchable on the database Skin Deep) that are linked to cancer. The average woman puts on 12 cosmetics products per day, yet only 20% of all cosmetics have undergone FDA examination and safety testing. The pharmaceutical giant Astra Zeneca can’t seem to decide if it’s for or against cancer. They produce the anti-estrogen breast cancer drug Tamoxifen, yet also manufacture the pesticide atrazine (under the Swiss-based company Syngenta), which has been linked to cancer as an estrogen-boosting compound. Breast cancer history month (October) is nothing more than a PR stunt that was invented by a marketing expert at… drumroll please… Astra Zeneca! Their goal was to promote mammography as a powerful weapon in the war against breast cancer. But as the American arm of the largest chemical company in the world, the reality is that Astra Zeneca was and is benefiting from the very illness it was urging women to get screened for. Perhaps the most audacious example of them all is pharmaceutical giant Eli Lilly. Sponsors of cancer research and treatment, both in medicine and the community, Lilly produced the cancer and infertility causing DES (diethylstilbestrol), and currently manufactures rBGH, an artificial hormone given to cows to make them produce more milk. rBGH has been linked to breast cancer and a host of other health problems. These strong corporate links in many ways explain the uplifting, happy, sterile messaging behind the pink ribbon. Corporations are, quite bluntly, making money off of marketing cancer, so if they don’t put a smiley face on the disease, they will alienate their customers and the conglomerate businesses pouring money into these campaigns.

Juxtaposed with the uplifting, bombastic, bright pink backdrop of the various cancer fundraisers and rallies, Pink Ribbons, Inc. quietly profiles the IV League, an Austin, TX-based support group for metastatic breast cancer. The women meet on a regular basis to share stories, help each other cope and accept the rigors of the disease and realities of dying. Many of the group members interviewed found current breast cancer campaign marketing offensive, tastelessly positive and falsely empowering (“If you just get screened and get mammograms and eat healthy, breast cancer can’t happen to you!”). The group, which has lost 10 members last year alone, is among a large faction of cancer sufferers that feel left out in the pinkwashing tide of marketing campaigns. Highlighting that sometimes you do get cancer because of no explanation, and sometimes you won’t respond to any treatment is a downer. It’s not the kind of uplifting story that advertising campaigns are built around, leaving the women feeling as if they’re living alone with the fact that they are dying. “You’re the angel of death,” remarks IV Leaguer Jeanne Collins. “You’re the elephant in the room. And they’re learning to live and you’re learning to die.” By utilizing powerful messaging keywords like BATTLE, WAR and SURVIVOR, cancer foundations and brands are subliminally putting down those who didn’t survive. And there are many who don’t survive — someone dies of breast cancer every 69 seconds. Are they suggesting that people who died or didn’t respond to treatment simply didn’t try hard enough? One of the most poignant moments in the film was an IV League Stage 4 cancer patient, probably weeks or months from her death: “You can die in a perfectly healed state.”

Although Pink Ribbons, Inc. is a sobering polemic against the mindless trivialization of commercializing breast cancer and even misdirecting funds from where they can be most helpful, it is not a hopeless film. Far from projecting pessimism, the film showcases the tremendous willpower and manpower that these three-day walks engender. It is simply misdirected. If hundreds of thousands of women and men can be motivated to fundraise, walk, run and (in some cases) jump out of planes, the effort is absolutely there to stop breast cancer. “Do something besides worry to make a difference,” concludes Barbara Brenner. “We have enormous power, if only we’d use it.” Director Lea Pool hopes that the film will encourage people to “be more critical about our actions and stop thinking that by buying pink toilet paper we’re doing what needs to be done. I don’t want to say that we absolutely shouldn’t be raising money. We are just saying ‘Think before you pink.'”

Watch the trailer for Pink Ribbons, Inc. here:

Pink Ribbons, Inc. goes into wide release in theaters nationwide June 8, 2012 and was released on DVD in September of 2012.

~*ScriptPhD*~

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development.

Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

]]>

“Ask your doctor if this hard-to-pronounce medication is right for you.” Sound familiar? It should. Over the last decade, it’s become difficult to watch an hour of television or read a magazine without running into a commercial for the latest cure for (insert disease here). For all of their ubiquity, the majority of ads are shockingly bereft of uniqueness. Bland, boring, and banal, they represent some of the worst of science creative in modern media. Here at ScriptPhD.com, we couldn’t think of a more appropriate category for the next installment of our ongoing advertising series “Selling Science Smartly.” Rather than expound on the plethora of bad pharmaceutical ads, we deconstruct a near-perfect Pfizer campaign out of Canada and interview the executive creative director behind the concept. Read our complete article under the “continue reading” cut.

Campaign: Pfizer “More Than Medication” (television, web)

Agency: Crispin Porter + Bogusky (formerly Zig Toronto)

Industry: Pharmaceuticals

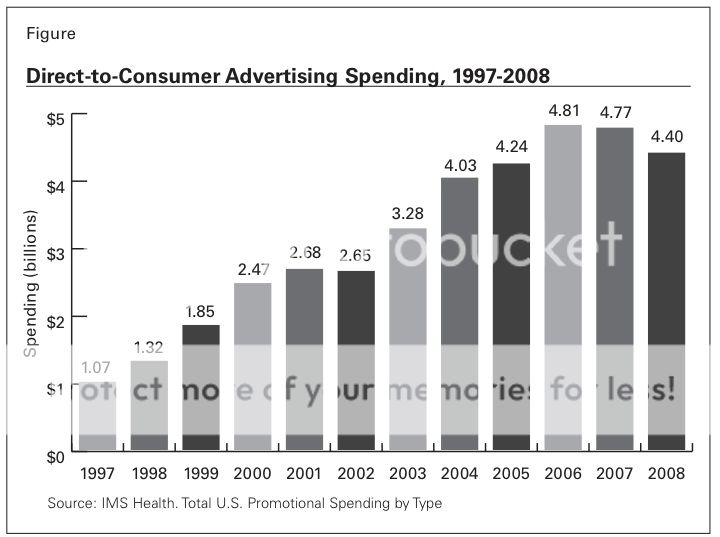

1999 was a seminal year in the long history of direct-to-consumer marketing of drugs and pharmaceutical products. No, this was not the year that they debuted. In fact, the selling of chemicals and potions goes back to the early 1900s, when deceptive patient ads (snake oil remedies) made up to 50% of advertising revenue for newspapers. Significant changes didn’t occur until 1938, when Congress passed the Federal Food, Drug & Cosmetic Act that stipulated, among other things, that a drug had to be proven safe and effective before it could be marketed. In the early 1980s, when marketing of drugs spilled over from medical professionals to consumers, the FDA requested a brief moratorium on televised ads, which it lifted two years later, requiring only that the ads include a brief summary of the drug’s side effects, contraindications, warnings, and precautions, and provide “fair balance” between the drug’s risks and benefits (see terrific review). It wasn’t until 1999 that the FDA greatly loosened these requirements, only asking that advertisers provide information about side effects in the audiovisual presentation. The rest, as they say, is history.

The result of this deregulation of oversight has been an outright torrent of television and print ads over the last decade peddling panacea for everything from depression to restless legs. The table above shows the steady rise in overall spending on direct-to-consumer marketing since the FDA amendment. While the recent recession has somewhat tempered spending, the sector has not suffered to the degree that others have. And while it is true that ad agencies have to contend with much more stringent FDA guidelines for required content (such as warnings, side effects, and medicinal purpose) for drugs than for almost any other product—a unique, difficult creative obstacle—the fact is, pharmaceutical ads are many, and many aren’t good.

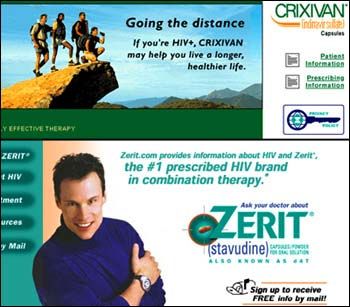

Remember that R.E.M. song “Shiny, Happy People?” It could be the anthem of the majority of pharmaceutical ads. You may not know what this medication is for, but it will make you smile as you run in slow motion through fields of sunflowers (assuming that you don’t have allergies; there’s a different commercial for that). Why not ask your doctor about it?? Take for example the egregious, bordering on offensive, 2001 print ad in the picture on the right for the HIV cocktail Zerit. A handsome, chiseled, smiling model in the foreground offers palliative assurance for a disease that scientists have found no cure for, while a group of background “patients” climb a symbolic mountain. The ad was roundly excoriated as the “Joe Camel of drug ads,” and even contributing to an epidemic of unsafe sex by making false promises and misleading impressions. (Actual side effects of HIV cocktail therapy can be so painful and debilitating that some patients refuse treatment.) According to an article in the trade magazine Advertising Age, just last year, the FDA admonished a group of 14 leading pharmaceutical companies for what it claims are misleading, misbranded ads on search engines such as Yahoo! and Google. Some wonder outright whether the proliferation of pharmaceutical marketing, now seen equally as a luxury for the healthy as a necessity for the sick, is having a deleterious effect on medicine.

It is within this cluttered field of profligate, if trite, advertising that an exceptional, authentic campaign out of Canada caught our eye. Geared towards encouraging personal health and wellness, the “More Than Medication” campaign for Pfizer by the Toronto office of ad agency Crispin Porter + Bogusky includes a series of well-produced, well-written television ads (mini-films, really) and a informative website. The storytelling within the two films, “Graffiti” and “Breathe,” is a particular highlight. We dare you to watch the first video, “Graffiti,” all the way through without crying.

Why it’s good science advertising:

The cleverness of CP+B’s “More Than Medication” campaign is 50% in the content that’s there, and 50% in the content that isn’t. Missing are the saccharine smiles, ridiculous athletic feats and idyllic dalliances of perfectly healthy people that never took the medication they’re purporting to be endorsing. Rather than portraying people who could be anyone (or, sadly, no one), these ads are the antithesis. “More Than Medication” is about life—mundane, radiant, lifechanging, heartbreaking. Through all of these milestones, Pfizer is attempting to build relationships one person at a time, and be a valuable presence in their healthy lives at their most important stages. Only time will tell if the campaign pays dividends, but as advertising strategy, it’s brilliant. Pharmaceutical companies rely on wholescale batch assembly at every stage of development, from searching for molecules as drug candidates, to researching them, to the mass production thereof. In fact, the fermentation tanks developed by Pfizer that enabled the first-ever mass production of penicillin during World War II became a national historic landmark in 2008. This doesn’t dictate that pharmaceutical ads must follow the same standard operating protocol.

Why it works:

Beyond “reinventing” pharmaceutical advertising, the “More Than Medication” campaign taps into an important (and growing) wellness zeitgeist being embraced by the professional and private health care sectors. Within the last few years, emphasis has shifted significantly from medication to meditation, pills to pilates, and technology to tofu. Individual preventitive care, including eating habits, exercise, healthfulness beyond chemicals, and individual responsibility, has been gaining momentum as a critical component of modern medicine, nowhere more than in how it is advertised. Kaiser Permanente’s enormously successful and popular “Thrive” campaign, recently expanded to the tune of $53 million, has echoes the welness call to arms of Canada’s “More Than Medication” spots. Internal documents indicate that the 2004 campaign was launched to combat a declining membership of 150,000 in a similarly reviled industry (health insurance). The initially modest reach has since expanded to print, outdoors, television and radio.

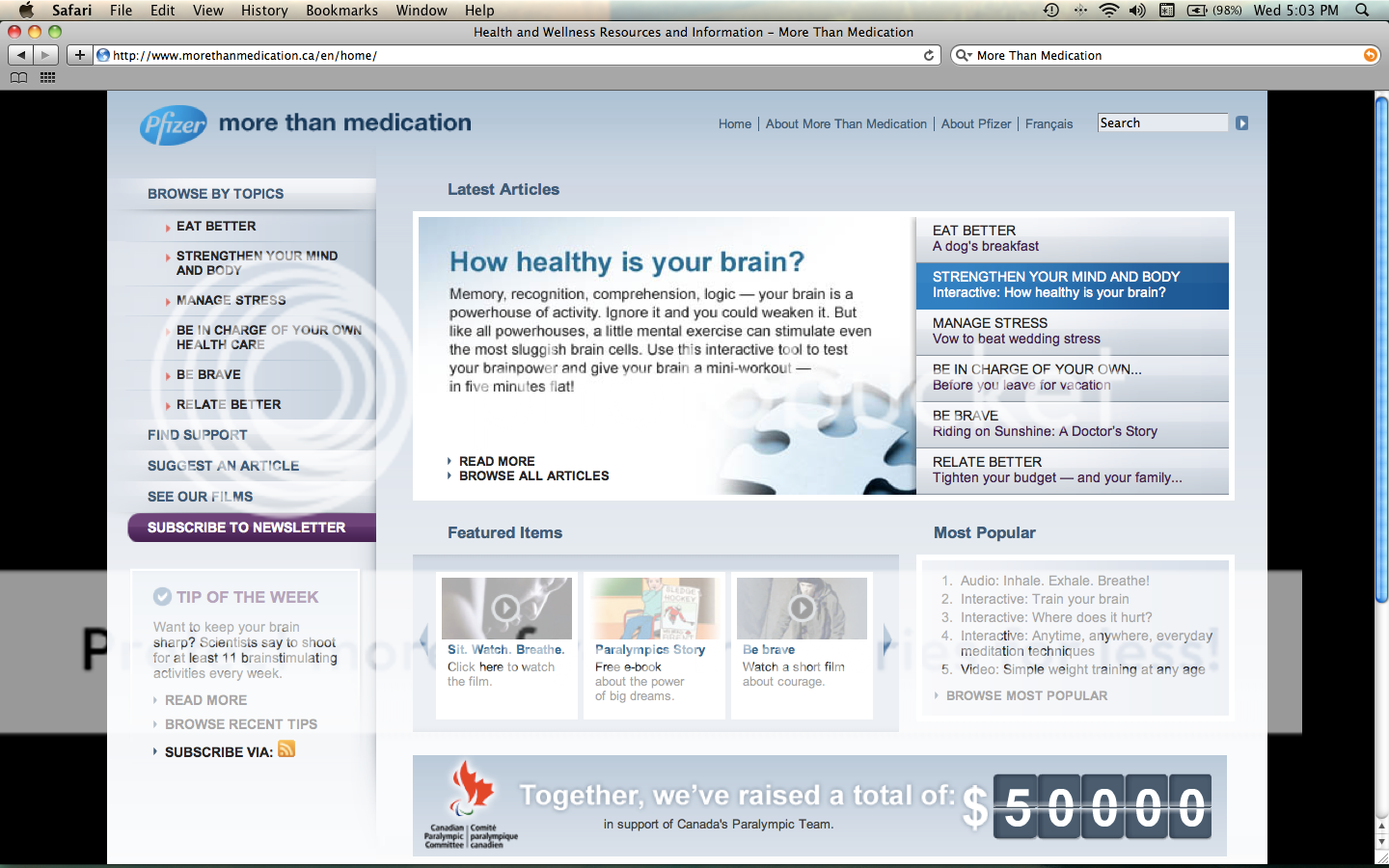

Pfizer supplemented their television spots with an interactive website that offers resources for individuals and their families, including eating better, strengthening mind and body, practical life tips, and places to find help to achieve these goals. In doing do, the pharmaceutical behemoth rebrands themselves as in touch, personally connected on an individual level and convey that they care about their patients’ health even if it means never having to take one of their medications.

What other science campaigns can learn from this one…

In Selling Science Smartly, don’t be afraid to be emotional. It seems like contradictory advice. Science and medicine are precise, technical and exacting, and needfully so. What they are not is antiseptic. Ask the medical doctor and nursing staff that spend days, weeks and months getting to know patients and integrated into their lives. Ask the patients and families who experience some of the most emotionally-charged moments of those lives (both joyous and sorrowful) in a hospital. Ask the scientist that slaves away at the bench in the hope that his or her efforts might save or improve lives. How do I know this last one? Because I was one of them. I did a large chunk of my PhD graduate thesis in a Novartis not-for-profit research institute doing drug discovery. My experiments led to a target candidate for acute myeloid leukemia (largely affecting young patients) which is currently being tested in mice. The exultation of a successful experiment and reward of hard work was far supplanted by pure elation at the thought that a life saved far in the future was because of my contribution. There is emotion in science and medicine; indeed, there can be no precision without passion. The role of a good creative is to extrapolate and harness it effectively. To all of my colleagues in labs and hospitals across the world and to all of the patients that their work ultimately affects, a campaign such as “More Than Medication” is a fitting tribute.

Questions for Aaron Starkman, Executive Creative Director—“More Than Medication” campaign for Pfizer

ScriptPhD.com: What was the client’s primary objective with this campaign and how did it lead to the development of the “More Than Medication” concept?

Aaron Starkman: The client wanted to create a bond of trust with consumers. Research showed that consumers don’t trust drug companies, and believe that they put profits before people. In Canada, we also have health care system issues with limited physician access and pressure on doctors to spend less time with patients. Canadians feel powerless when it comes to their health.

We knew that in order for Pfizer to build trust, we had to show Canadians that Pfizer’s point of view was different from other pharmaceutical companies; that, as a company, they believe that wellness is not achieved by taking pills, but about a more holistic, balanced approach that doesn’t require any of their drugs at all. “More Than Medication” was the freshest and clearest expression of our core idea. It takes a lot of people by surprise that a pharma company would take such a stance.

SPhD: Big pharma can be publicly perceived as a bottom line, profit-driven pill dispenser. Additionally, people’s eyes tend to glaze over when dealing with any scientific or medicinal concepts. How did these dual challenges figure in the ultimate mapping out of the “More Than Medication” campaign?

AS: We couldn’t let the work we did reinforce any of the negative perceptions of the pharma industry. We took the completely opposite tack to traditional pharma campaigns which typically focus on research and innovation and how that benefits people. Ultimately, those messages don’t resonate because they are company focused, not people focused. To break through, Pfizer had to shed all of the baggage and aim for a more insightful, emotional high ground which no other pharma company has done, even to this day.

SPhD: The “Be Brave” and “Breathe” videos for this campaign have a tremendously cinematical composition and emotional resonance, above and beyond the feel of a typical :30 or 1:00 ad. Can you speak to the creative development of these “mini-movies”?

AS: Internally, we refer to them as films. And that’s how our director John Mastromonaco treated them. John is a brilliant director and he’s really amazing at developing characters quickly. In “Be Brave” viewers go from feeling that the main character is a thug, to empathizing with him, to getting to know his family, to realizing he’s an amazing brother and a good person- that’s a lot. But John and his production company Untitled Films really believed in the project and the message Pfizer wanted to convey. And they were amazing partners throughout both projects.

SPhD: The ad campaign was launched in 2008. What has been the tangible impact to Pfizer and across Canada?

“More than medication” is more than a campaign – it’s a mantra that has positively impacted how Pfizer behaves as an organization. It’s been culture shifting for them. Externally, it has raised brand scores across a variety of metrics, trust being one of them.

SPhD: Biggest piece of advice for tackling an unorthodox campaign in a technical or dry field (in this case biotech/pharma)?

AS: Be brave.

SPhD: What’s a current ad campaign or creative concept that you really like and why?

AS: I love a non-traditional campaign from Sweden for Swedish Postal Service. They created their own celebrity called ‘Stefan the Swopper’. This guy became famous because he used social media to get out his message. And his message was that he wants to trade every single thing he owns – from his car right down to his toothbrush and boxer shorts. When people asked for details on how the swapping can work, Swedish Post’s service was revealed by Stefan. The campaign was an unbelievable success and a revolutionary way for a client to launch a service.

Take a look at this short video chronicling the clever ‘Stefan the Swopper’ viral campaign construction and its effects in marketing the Postal Service in Sweden:

ScriptPhD.com gratefully thanks Stephen Sapka and Aaron Starkman from Crispin, Porter + Bogusky for their time, coordination and enthusiasm for this project.

~*ScriptPhD*~

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development.

Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

]]>Who among us has not computerized our bills, thinking that reducing paper consumption was more Earth-friendly? Or increased accomplishing anything and everything by email that used to be done by snail mail? On a larger scale, media and advertising (and to some degree entertainment) has had the same idea, moving away from traditional print to digital delivery models. At the Sustainable Media Climate Symposium in Manhattan last December, Don Carli spoke about the new and somewhat controversial concept of ‘Tree Washing’ within the advertising and media industries, specifically the notion that modern technology use and methodologies leave a larger carbon footprint than the traditional paper industry:

The video, and idea, caught ScriptPhD.com’s attention in a big way. Mr. Carli, the director of the Institute for Sustainable Communications, has hypothesized extensively about whether digital media is worse for the environment, including a recent white paper about the guilt that this new dilemma has incurred in consumers. Eager to learn more, ScriptPhD.com sat down with Mr. Carli to discuss the technology and environmental challenges presented by modern media and advertising conduits, how technologists and creatives can work in concert with environmental and watchdog organizations to mitigate these challenges as technology continues to evolve in our lives, and why it’s in businesses’ and brands’ best interests to compact carbon footprints. For our complete interview, please click “continue reading.”

ScriptPhD.com: We have talked before about your unusual background, which started off quite in the traditional artistic realm, before pursuing the more technical aspects of advertising and media deconstruction. Can you talk about that and how important it was to fuel your later passion?

Don Carli: I suppose you can say one thing leads to another, but it really has been a journey that began with an undergraduate degree as a liberal arts major. You learn to learn, you don’t learn anything in particular. As a liberal arts major at St. Lawrence University in Upstate New York, we were encouraged to study broadly and to double-major if we sought. So I started out as a biochemistry major, but found I enjoyed literature more than titrations, so I changed my major to English Literature, and at the time my roommate was (and still

is to this day) a sculptor, there undertaking a career in the fine arts. He’s a very successful man by the name of John Van Alstine. I was kind of interested in what he was doing, so I decided to double major, but I didn’t leave the chemistry behind. I’ve always been interested in, first of all, how we communicate as a species, and literature is one side of the brain and visual arts are the other side of the brain. Underlying it all, I was always interested in the science and the chemistry that makes it all possible. As an example, when I was studying art in printmaking, I wanted to understand what the pigments are made of, and when I was studying ceramics, I wanted to know what makes the glazes the colors that they are. I was the kind of art student that would walk over to the geology department and then do forensic analysis of the dyes and glazes and pigments. So I was always a left-brain/right-brain, quantitative/qualitative student of learning. In my studies, it was clear to me that the challenge that I’d face (and that we continue to face as a society) is reconciling these very different two cultures of the sciences and the arts. So a good deal of my career has been trying to resolve that conflict, trying to fuse those irreconcilable opposites into some synthesis that identifies or unlocks value.

SPhD: Let’s talk about that a bit. Before we get into the heart of some of the things you do with the Institute for Sustainable Communication, we need to define some loosely thrown around terms for folks that may have kept hearing them, but aren’t exactly sure what they mean. The first is greenwashing. We hear this term a lot, but very few people take the time to expound on it in-depth. Can you help us define what it is and why is it such a threat to advertisers’ creative content and the consumer?

DC: It’s related to the term whitewash, where you try to cover something over. Greenwashing is basically the practice of making environmental claims, or claims of being “environmentally friendly,” that don’t necessarily reflect the underlying reality. In effect, it’s deceptive use of green claims. Perhaps the best guide or articulation of what are called the “Seven Sins of Greenwashing” is a white paper that was developed by the environmental marketing agency TerraChoice. In Canada, TerraChoice also manages the Eco Logo program, the environmental labeling program that uses international standards for eco-labeling. In the “7 Sins of Greenwashing,” the sins are laid out—such as the sin of Hidden Tradeoff. That’s where you make some claim about a product without disclosing that there’s a hidden tradeoff, some dark side. Another [sin] is No Proof, where essentially you make a claim, but you don’t back it up. Or the sin of Vagueness, where the claim is so diffuse that you can’t really be held to any sort of criteria of judgement. And there are others that you could go on and on.

All of these things taken together undermine advertising and brands. At the end of the day, markets are dependent on trust by individuals of actors in the marketplace. So if Company A makes earnest efforts to quantify the environmental benefits delivered by its products or services, and to invest in the certification of those claims using sound scientific evidence, and then Company B simply makes a claim without substantiation, or a false or irrelevant claim, or tries to shift the burden from one area to another, that really diminishes the value of that other effort. So it’s very important that in markets, not only do we have rules, but that there’s enforcement of them so that we can trust that when something is said, it’s got meaning.

SPhD: That leads beautifully into my second point that I wanted to clarify with you, which is the notion of media supply chains. What are they?

DC: First of all, the Institute for Sustainable Communications is a non-profit that was founded a little over eight years ago. At the time, it was our realization that while there were many efforts being undertaken to use green marketing language and imagery, there was an almost wholesale avoidance or failure to recognize the environmental impacts of the media that were being used to carry out the messages. So, for us, a medium can be a magazine page, a newspaper, a billboard with LED lights, a web page, email and so on. Frankly, it could even be experiential media, like an event. But in every one of those cases, the medium involves flows of energy, flows of material, flows of waste, and patterns of human activity and information that have significant impacts. Unfortunately, most of those impacts are undocumented or unknown—they’re kind of the monolith hidden in plain sight. So the institute’s declared roles are to raise awareness of those media supply chains, and also to build capacity. They’re not just an environmental attack group. We work constructively with companies of all types, get them to understand that all of their communications media choices have environmental impacts, help them to quantify those, work with them, and help them to manage those impacts in a way that is good for business—not just less bad, but environmentally restorative.

SPhD: When you talk about media messages being “dissonant,” what do you mean by that?

DC: It kind of reminds me of even when you can’t sing, unless you’re totally tonedeaf, you generally can tell if someone is out of tune or off-key. And that grates us, it bothers us. From birth, we’re very conditioned to recognize dissonance between what people say and what they do. We have a highly evolved sensibility to identify politicians who say one thing and do another, parents who say one thing and do another, and yet, here comes the marketing industry that increasingly is using green messages. In many cases, they’re using genuine efforts to improve the formation of their products, the chemistry that they’re made of is greener, and to improve the environmental profile or sustainability of their packaging. To use less material, to use renewable and compostable material… and yet, characteristically, they tend to ignore the sustainability aspects of their advertising, their marketing/communications and their promotion activities. So consumers really aren’t stupid, and they can see, once they’re made aware of what the flows are, that there’s a disconnect. I think there’s an opportunity for brands to walk the talk, to demonstrate their commitments or their beliefs and values, not only in their products and packaging, but in their advertising and promotion, the way they employ people, energy, materials, and the way they manage waste.

SPhD: Technology and media aren’t going anywhere. If anything, they’re proliferating, especially now with the iPad’s successful launch. Social media is stronger than ever. You’ve talked a lot about the idea that just because something is digital or electronic, doesn’t necessarily mean that it’s more green or tree-friendly. So, how do we piece together our growing need for consumption of e-media and the fact that it’s potentially devastating to the environment?

DC: You can’t manage what you don’t measure, and you can’t measure what you don’t identify. So you have to start by identifying where is the energy and material that makes it possible for me to advertise in any media coming from? The second question to ask is is that the most efficient use of energy or material—is it even necessary? Could I use less of it? And if I have to use it, is the energy renewable? If the answer to that is no, then we have to ponder whether there is a way to change the supply chain, the sequence of business activities that make it possible for me to do that, and still achieve my business objective. So we need to develop standards for product categories in advertising. We don’t have those today. We have standard units that are employed in banner advertising, but if you wanted to compare the carbon footprint of a banner ad to the carbon footprint of a magazine ad, the product descriptions don’t support those comparisons.

An example would be snail mail and email. We are extremely conditioned to believe that traditional mail is an annoyance, is bad, is environmentally impactful, and that email is better, or that digital communication is environmentally preferable. If you wanted to compare one dimension of physical mail and email, let’s say its carbon footprint, you have to have a unit of comparison. Today, the mailing industry describes a unit of mail as one gram of mail. How do you compare one gram of physical mail with its counterpart in email? There’s no weight. So as industries, first we need to develop product definitions or category definitions that allow us to make objective comparisons among and between different categories of communication. So a marketer, for example, can now create a media plan that uses 5 or 10 or 15 different media types to touch prospective and current customers with a message. And for each of those, to know how effective it was, what its economic costs were, as well as what its environmental and ancillary social impacts were. It’s not rocket science, it’s just accounting! But it’s accounting that we’re not doing today because, frankly, no one asked us to.

SPhD: What has been the response from the advertising and media industries to a lot of your efforts?

DC: We’ve been at it for about ten years. I’d say initially, I felt somewhat like a dog howling at the moon. Now it’s a little bit more like the dog that caught the car. There are advertisers and advertising associations that are listening and working with us now. Their change of heart and mind has really evolved as the recognition of sustainability performance or economic/social triple-bottom line performance has become more of a concern for regulators, with the SEC, particularly institutional investors, large retail chains like Wal-Mart, and to a lesser degree, to consumers. As those other interest groups have said that this idea of measuring the economic and environmental and social impacts of the business corellated with success and risk, we think it’s important to pay attention to it. An example of that from the last few weeks: Intel’s board acknowledged that sustainability performance reporting is a fiduciary responsibility. That’s a big deal. So once the reporting and identification/quantification is seen as a fiduciary responsibility, it changes the whole dynamic.

SPhD: As a consumer, what do we do?

DC: Well, the consumer ultimately holds the brand accountable. And we’ve seen study after study say that while consumers won’t pay more for a green brand, they will punish brands that they see to be irresponsible by not buying it. Even worse for the brand is that while a loyal consumer may tell one friend, a disaffected consumer will tell ten. So in this fishbowl world we live in, Facebook-Twitter-YouTube exposure, it’s kind of a synopticon. A brand can’t hide any longer—the activities of its supply chain, where its energy comes from, where its materials or labor come from. Sooner or later, someone with a cell phone camera will send an SMS and it’ll wind up on Twitter, and the next thing you know, it’s in the mainstream media news cycle within a day. And overnight, bilions of dollars in brand value can be destroyed.

When it comes to the media supply chain, it’s not that they have such egregious wrongs in them. It’s just that in aggregate, advertising and media supply chains represent about 10% of our gross domestic product. Advertisers in the United States spend on the order of $150 billion per year on paid media. That $150 billion is just to buy the space. That unleashes a whole cascade of business activities that involve mining, agriculture, forestry and transportation, retail, distribution that collectively represent about a trillion dollars or more of our GDP. So, there is no one company or brand that buys enough advertising to have concentration of influence. Even the biggest advertiser in the world spends on the order of $10 billion dollars out of $150 billion or more, so even if they were to lay down the law, it wouldn’t make much of a difference. There’s no functional equivalent to Wal-Mart in the world of advertising. If there was a concentration of 30-40% of ad buys in the hands of one company, there are so many different types of media and media supply chains, that there isn’t sufficient leverage in terms of impacting those different choices. So it is a challenge, but it’s not completely intractable. It begins by a recognition of a group of the largest brands that they need to quantify where the flows of energy and materials are, and to what degree they are at risk of changing that might hurt their business, the environment or society. Once they’ve gotten that picture, then it’s possible to change things.

Don Carli is a Senior Research Fellow with the nonprofit Institute for Sustainable Communication, where he is director of The Sustainable Advertising Partnership and oversees programs addressing advertising, marketing, corporate responsibility, sustainability, and enterprise communication. He is also a member of the board of advisors of the AIGA Center for Sustainable Design. If you have ideas for Don about what he discussed above, or want to learn more, follow him on Twitter @dcarli.

~*ScriptPhD*~

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development.

Follow us on Twitter and our Facebook fan page. Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

]]>

Here at ScriptPhD.com, we pride ourselves on being different, and we like thinking outside the mold. So for Earth Day 2010, we wanted to give you an article and a perspective that you wouldn’t get anywhere else. There is no doubt that we were all bombarded today with messages to be greener, to use less, to be more eco-conscious, and to respect our Earth. But what is the underlying effect of advertising that collectively promotes The Green Brand? And has the Green Brand started to overshadow the very evil—environmental devastation—it was meant to fight to begin with? What impact does this have on the future of the Green movement and the advertising agencies and media that are its vocal advocates? These are questions we are interested in answering. So when we recently met Matthew Phillips, a Los Angeles-based writer, social media and branding expert, and the founder of a new urban microliving movement called Threshing, we were delighted to give him center stage for Earth Day to offer his insights. What results is an intelligent, esoteric and thoughtful article entitled “Plastic Beads and Sugar Water,” sure to make you re-evaluate everything you thought you knew about going green. We welcome you to contribute to (and continue) the lively conversation in the comments section.

“Access to land provides access to food, clothing, and shelter—which means access to land provides the possibility of self-sufficiency—if anyone wants to maintain a dependent (and therefore somewhat dependable) workforce, it’s crucial for you to sever their access to land. It’s also crucial that you destroy wild foodstocks: why would I buy salmon from the grocery store if I could catch my dinner from the river? Now, with people having been effectively denied access to free food, clothing, and shelter, which means having been effectively denied access to self-sufficiency, if they are going to eat, they’re gong to have to buy their food, which means they’re going to have to go to work to get the cash to buy what they need to survive. If you’re a corporation, you’ve got them where you want them.” —What We Leave Behind.

I have a great deal of admiration for our original permaculture engineers, the American Indians, all grass fed bison advocates. Looking back, we can’t imagine how naive or gullible they were to accept fire, water, plastic beads and useless trinkets in exchange for their healthy animals, fresh fruits and vegetables, consulting knowledge, and land—whose value is incalculable. Interestingly, here we are 518 years later, and we’ve all been duped into giving up our valuables for well marketed sugar water, and filtered tap… in plastic bottles.

After 1492 the American colonization effort was dominated by the European nations. In the 19th century alone, 50 million people left Europe for the Americas with ‘old world’ diseases, and a manifesto to massacre, obliterating 42 million American Indians. Everything changed; the landscape, population, plant and animal life. A few pioneers with rebel attitudes proved they could kill, conquer, and dominate an entire people and their land. What have we learned? When you deprive a group of people access to their land, you dominate and control their self-sufficiency, and ultimately their sustainability.

Earth Day was designed from its inception, April 22, 1970, to inspire awareness and appreciation for the Earth’s environment. Like all successful grassroots movements, Earth Day continues to self-organize and experiences annual growth. Over the years, it has propagated thousands of related causes or brands. This celebration gives us the opportunity to contemplate how to purchase food and drink that are produced locally through natural, sustainable methods. Whether we graze together, or barbecue grass-fed bison, I anticipate that many foodborne conversations will thresh organic ideas that seed new urban backyard businesses, and energize sustainable causes.

In fact, in this past year, we have witnessed local production and sustainable social causes grab the wheel from the generic “Green” brand. ‘Local and sustainable’ terms have the potential to drive significant impact in helping redefine a movement whose banding terminology is arguably out-of-focus. The Green goal has not achieved our Garden of Eden fantasy. Many generic Green causes have become distracted watching, and often joining, the fight against their ‘evil,’ instead of cultivating community and encouraging positive purposeful action. We’ve seen new Green causes sprout through PR dusting designed to crowd out similar already established causes. There’s nothing wrong with competition, seeking a bigger audience, news, press, and ultimately funding, but often the next new Green cause articulates greater Green evils in an attempt to further establish its reason to rally. This problem is churned up further with traditional reports broadcasting emotionally charged sound bites. Reporters often don’t take the effort to dig past the easy emotional approach, and into the rich cream of the cause itself. It is much easier to philosophize about the negative, which can feed our illusion of intellectual superiority, but it’s really keeping our callus-free hands from getting dirty planting GM-free maze in the garden and producing oxygen. “The creation of something new is not accomplished by the intellect but by the play instinct acting from inner necessity. The creative mind plays with the objects it loves,” said Carl Jung.

A great brand seeks to unify in a cyclical system: Magnetizing believers, educating, generating action, and finally producing evangelists, who then magnetize new believers and so on. Memorable brands are most effective when they are communicating their power and concept through story. At its most basic, a brand’s story is made up of the hero, (relating to the brand’s reputation and hopefully positive recognition), and its evil, (the perception of what hinders recognition of the brand). Clarifying the adversaries of the brand can help to ‘rally the troops,’ codifying their cause and movement. Without an adversary, it’s often difficult to get enough of a rouse from fellow partners to get anything started.

Every great brand needs an evil to fight, but Green’s evil has metastasized into the most unimaginable catastrophe that no cause could ever compete against—an over heating planet. Since it doesn’t get much worse than a gooey globe due to our ongoing abuse, this heat enemy seemed guaranteed to become THE unifying force, an evil that we could all fight together to overcome. The problem is the scope is too large to control or confine. It has mutated. Proving global warming has the potential to fracture the green community, and along the way has produced a number of serious critics. Terms like ‘climategate,’ and climate skeptics like Doug Keenan, continue to look at research they say is embellished to promote climate change. Maybe worshiping the over heating demon has made the ‘Green’ brand seem boring compared to the excitement of the fight. Google never defined its “Don’t be Evil,” last minute tag, which is part of the reason it continues to generate conversations across the board. Google has essentially allowed all of us to insert our own definitions of evil, which in effect has unified greater numbers to their brand. A very novel approach.

If the evil of a brand consistently gains more press than the cause, then the evil assumes and replicates the identity of the brand. When this happens, the brand is no longer the host. When the evil forcefully sucks all the nourishment from the brand’s beating heart, then the evil we were fighting becomes the cause. We feel more comfortable with our fingers on the keyboard dealing intellectually with evil, which in effect, removes our foot from the shovel of physical, sweaty action. Do we want to get back to the heart of the brand, the original cause? Harley Davidson, once perceived as the brand of choice for rebels and tattooed ex-cons, re-branded itself and become the hog of choice for everyone who could scrape together enough money, regardless of prison experience, body type, tattoo placement, or gender. Even our kids wear official HD branded fashion with pride.

If we stop promoting the evils, real or manufactured, and start encouraging positive actions and solutions, (often positive action is the best offense against perceived evil anyway) we’ll find passionate people that want to join us in healing our people and planet. The strategic approach to refresh a brand is extremely important if it is to succeed. Digitally empowered consumers want to punish those that don’t behave in a socially responsible way and reward those that do. Social media has given people real power to act, and also to be negative. “Social media is inherently more negative than a positive medium on many levels,” said David Jones, the global chief executive of Havas Worldwide. “Lots of stuff that is passed around is negative. If you are a brand or a company today you should be far less worried about broadcast regulations than digitally empowered consumers.”

Many will continue to base their directive on creating new enemies, using ‘the fight’ to impassion those around them to rally their cause. Stop depleting the ozone layer, reduce your carbon footprint, global warming. All grand Green, but terminology that is technically fear-focused. We’ve heard the pitch: “It is your investment of $59.95 that allows us to partner together to fight this injustice.” The fear based, negative approach is almost always wrong, (unfortunately, it can be effective) . It’s a slippery slope, and those who don’t fully embrace the creed, are either stamped ‘stupid,’ or ostracized. But sustainability should be positive at its core. There is a time to debate, and we’ve debated ourselves into the greatest recession any of us have ever experienced. It’s time to stop debating.

Let’s begin by forming communities that build sustainable ventures together. If we are fighting, or politicking, we are not building. “We have become divided into so-called red and blue states, an outcome directly traceable to the urban-rural division of our society. This is something of a simplification, but food producers and their social allies tend to vote red and food consumers and their social allies tend to vote blue. The division is thought to be between conservative and liberal philosophies, but it much more reflects the difference between rural and urban values,” said Gene Logsdon.

There are two real challenges within the sustainability movement:

1) Consumers’ decisions (especially with food) are splintered by: A) Convenience, B) Tradition, C) Bias, and D) Beliefs.

2) Industry’s “manufactured demand” is affecting consumers with: A) Deceptive advertising, B) Ambiguous terminology, C) Perfectly designed plastic convenience packaging sealing our addictive lifestyles.

The minute we wake up we are subjected to an eco-plastic, part of this complete breakfast, 100% edible, industrialized high fructose corn syrup, brand campaign. Industrialized conveyor belts are pumping out a marketing product of starch coated with refined sugar. We can reignite our camaraderie by producing fruits, vegetables, animals and vehicles that not only compete, but surpass, our current available choices; all sponsored of course by our very green desire for sustainability. Incidentally, the average number of ‘green’ products per store almost doubled between 2007 and 2008. Green advertising almost tripled between 2006 and 2008. Does this necessarily mean we are heading in the right direction?

Governmental regulations for consumer protection in industrial food processing plants have only added to an already over stressed food system. This industrialized hyper-efficiency has caused diseases in animals and bugs on crops that have been taken so far out of their natural ecosystem that they can no longer produce without heavy use of antibiotics and pesticides. These measures, of course, were designed to keep us safe, but instead have become another major concern since “packaged nourishment” comes from the industrialized, often treated, food system.

Creatives are beginning to find and tell the stories concerning the overly subsidized and industrialized food and distribution system which favors use of pesticides and antibiotics. Since the government historically is not very good at spearheading movements, artists (media pioneers, authors) and social entrepreneurs will continue to fill this leadership role. We don’t have to look far to see powerful results. Thank the documentary filmmakers of Food Inc., Supersize Me, HomeGrown, The Future of Food, Story of Stuff, and Bottled Water, for helping us become visually aware of how industries have been deceiving consumers and themselves in their interest of greed and everyone’s desire for convenience. But there is hope, and it’s simple. Consumers are communicating online like never before, this leads to uniting together to strategically direct where we spend our hard earned bread and where we plant or raise our own food.

Jamie Oliver’s new TV series, The Food Revolution, has exposed the frozen fat underbelly of pre-packaged (brown and gold) foods, and government charts that officially dictate the clogging of our kids in school. Local and “real” food production and consumption has become a legitimate genre, with universities, and high schools requiring reading of titles like Barbara Kingsolver’s Animal, Vegetable, Miracle, Michael Pollan’s Omnivore’s Dilemma, Bill McKibben’s Deep Economy, among others. These authors are helping us move past intellectual reasoning and into action. Since Timothy Ferrass taught us how to achieve a four hour work week, some of us among the fortunate now have the extra time to plant some seeds, water, and grow great big vegetables, and share them with our friends and neighbors.

I believe that in the next decade we will see less of an emphasis on extrinsic, materialistic values and more on intrinsic, spiritual values. This shift in emphasis will begin to bear fruit with the collaborative grafting between creative media pioneers and social entrepreneurs who seek to disrupt the status-quo. Research from San Francisco State University has shown that experiences bring people more happiness than material possessions. Experiences shared with others continue to provide even greater happiness through memories long after the event occurred. I believe many social entrepreneurs and creative media pioneers, in their hearts, believe their core purpose is to encourage our return to a sustainable world ecosystem. In other words, many will forgo Hummer-sized riches in order to nurture the successful adoption of their creations into society. There remains however ambiguity in the complexity that lies between the producer and the consumer. The ancient system of distribution gives middlemen the leverage to manipulate both producers and consumers. This too is evolving, as producers return to their roots and begin to distribute locally. There is change in the air, spring is coming.

We are at such a nascent stage in the evolution of the sustainable movement. The infrastructure necessary for the modern city to relocate to the farm is exorbitant, but the farm is beginning to integrate into the metropolis, one yard at a time. ‘Off the grid’ produces many wonderful connotations. It is an adventurous subject, one that I’m convinced will help propel this branding conversation forward. I wonder who else is discussing the connections of the ideas from this article, and from the authors and media pioneers mentioned? Who are the artisans, and social entrepreneurs that are working on this? Very curious about your thoughts. Please don’t hesitate to email me, and please act.

Let’s continue to find new ways to unify this brand with wonderful heart felt stories about the adventures of locally produced products, urban farms, and sustainability.

Writing this has given me a renewed appreciation for early American Indian cave drawn stories of food: adventure, and victory. There is more there than I had imagined.

Matthew Phillips is a media producer, writer and technologist working in Los Angeles, CA. He is the producer of Threshing.

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development.

Follow us on Twitter and our Facebook fan page. Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

]]>

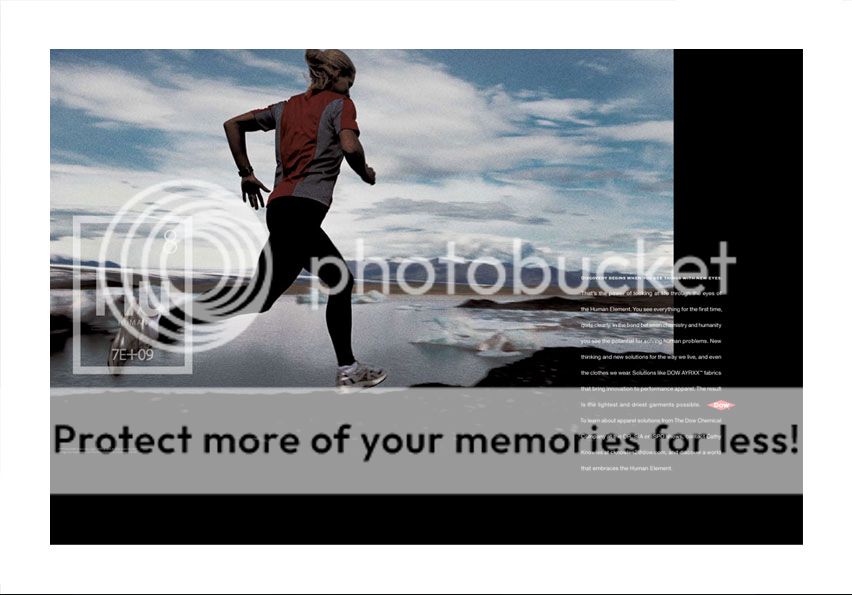

When it comes to the interface of art and science, in many ways Madison Avenue finds itself in the position of the early days of sci-fi entertainment, where campy, unrefined productions took decades to evolve into the sophisticated films and shows we enjoy today. To be brutally honest, 95% of current science and technology advertising ranges from hackneyed to terrible; unimaginative, uncreative, uninspired. But here at ScriptPhD.com, we want to focus on the superlative 5%. What makes these campaigns work, what elevates their content above the crowd and most importantly, how do they fit within the theme of the science or industry they are promoting? This is why we are expanding our umbrella of coverage—which has heretofore included film, television and media—to the final frontier: advertising. In our brand new series entitled “Selling Science Smartly,” we will profile the best that science and technology advertising (print, TV, radio, digital and everything in-between) has to offer. Where possible, we will interview the respective campaign’s agencies and creative teams to give you a rarely revealed behind-the-scenes purview into the process and foundation of making these ads. We are proud to launch the series with the exceptional Dow Human Element campaign, including an in-depth interview with Creative Director and mastermind John Claxton of Draftfcb Chicago, who breaks down the thought process behind the creation of the campaign.

Campaign: Dow Human Element (print, television, web)

Agency: Draftfcb Chicago

Industry: Chemistry

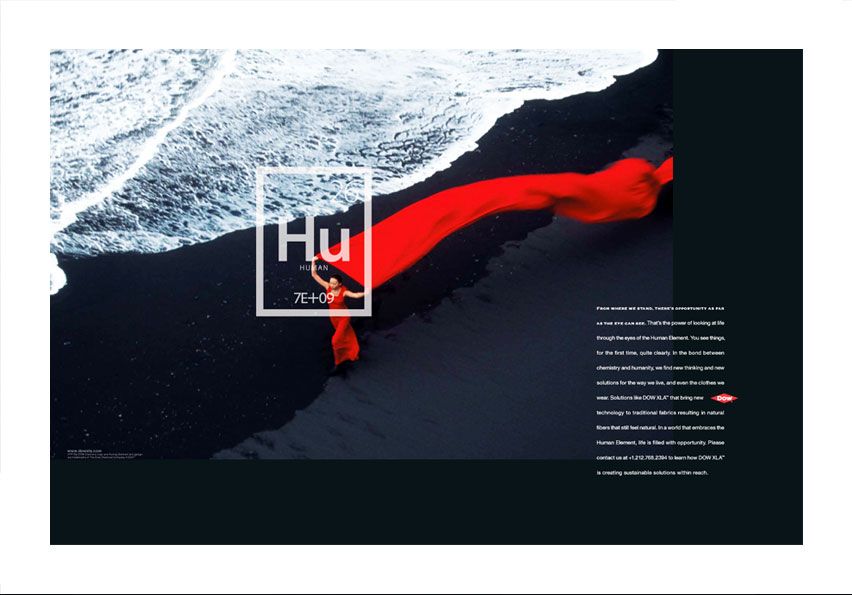

Originally founded in 1897 by Canadian-born chemist Herbert Henry Dow, Dow Chemical Company is the second-largest chemical manufacturer in the world. Their primary output is plastics, including familiar products such as Styrofoam, Saran Wrap and Ziplock bags, but they also produce agriculture and performance chemicals, as well as hydrocarbon and energy materials. In 2006, Dow hired advertising agency Draftfcb Chicago to rebrand its image, with a corporate focus on working together to apply science to improve the human condition. The campaign was called “The Human Element” and was the recipient of a 2008 Effie Award for Corporate Reputation, Image and Identity. ScriptPhD.com has chosen this campaign for our Selling Science Smartly series because we feel it embodies a perfect combination of creativity, risk-taking, effectiveness and uniqueness to represent science at its pinnacle. Take a look at some of the spots below:

All images and logos ©Dow Chemical Company, all rights reserved.

Why we like it:

How many times have you seen a formulaic pharmaceutical ad that could interchange virtually any product or drug without batting an eyelash? Or my personal pet peeve—a generic science ad with the now-standard happy researcher staring off into the sunset holding up a test tube of colorful liquid? These images are safe, boring, and ubiquitous. What makes The Human Element stand out is that it’s striking, gorgeous, poignant, different. The images within these ads are evocative, sensual, and they tell a story. The most recent versions of the campaign (pictured on the left) include the stunning photography of National Geographic photographer Steve McCurry. In advertising, the product is King and is showcased as such. However, in the case of science and technology, this leads to the same over-used imagery and tropes. It takes a lot of skill and bravery to attempt to tell a science story using abstract ideas, and I love that Draftfcb was willing to try. Because it has storytelling at its heart, this campaign is also malleable and adaptive to longevity, having just launched a series of supplementary web videos.

Why it’s good science advertising:

Dow is a chemical company. They make chemicals. Using chemistry. This is their central corporate identity, and no advertising campaign would be complete without using that as its foundation. With a logo representing a “missing” element of the periodic table, and copy evoking the language and reaction processes of chemistry, The Human Element campaign condenses the most basic substance of what Dow Chemical does. With that logo containing an atomic number representing the global human population, it becomes instantly intimate and conveys the idea that science serves to advance humanity. Aesthetics aside, it’s a functional piece of branding that concomitantly reminds us the history of what Dow Chemical was established to stand for and looks forward to what it can achieve in the future.

Why it works:

The Human Element struck me, in essence, as a corporate rehabillitation campaign, and it succeeded on that level. While it has given us some practical and even beneficial products, Dow cannot escape a litanny of environmental transgressions (Union Carbide disaster in Bhopal, India) and the shame of being the sole provider of Napalm during the Vietnam War. CEO Andrew Liveris has expressed firm commitment to continuing an environmentally-sustainable corporate strategy, which has included successful collaboration with The National Resources Defense Council and being named by the EPA as the 2008 ENERGY STAR Partner of the Year for excellence in energy management and reductions in greenhouse gas emissions. One year into this advertising campaign, not only did the stock price of Dow appreciate 29%, but more importantly, their brand-equity rating skyrocketed by 25%. Secondly, large corporations such as Dow, particularly those in manufacturing industries, are conflated by activists and even ordinary citizens with greed, arrogance, environmental insouciance, and downright evil, something ScriptPhD wrote about earlier this year. These highly adhesive visceral impressions can be difficult to break. The Human Element campaign shows a subtle awareness of this fact, and, by focusing on people and nature, humility. Finally, Sandy Colkey, Executive VP at Draftfcb and head of the Dow campaign, commented that the ads were also effective in recruiting green-minded chemists and scientists to Dow, which only reinforces and amplifies the purpose of this campaign to begin with.

What other science campaigns can learn from this one…

The scientist does not study nature because it is useful; he studies it because he delights in it, and he delights in it because it is beautiful. If nature were not beautiful, it would not be worth knowing, and if nature were not worth knowing, life would not be worth living. Of course I do not here speak of that beauty that strikes the senses, the beauty of qualities and appearances; not that I undervalue such beauty, far from it, but it has nothing to do with science; I mean that profounder beauty which comes from the harmonious order of the parts, and which a pure intelligence can grasp.

– Henri Poincaré, physicist, mathematician and science philosopher

In Selling Science Smartly, don’t be afraid to be beautiful, lyrical and poetic. Science is a tool that utilizes rigor, precision and experimental design to reflect the natural beauty and wonder that does and can surround us. Moreover, the most analytical, objective scientist still has to employ out-of-the box thinking to stumble on a new discovery or solve a difficult puzzle. Good advertising should strive to communicate that. One of the biggest weaknesses (and challenges) in science advertising is resisting the temptation to construct campaigns with the same linear process that science experiments are fundamentally built around. Infusing creativity, lyricism and a humanist perspective help to make these ads accessible and empathetic, all qualities achieved superbly by the Human Element spots.

Interview with Draftfcb Creative Director John Claxton

The Human Element campaign was conceived and crafted by Draftfcb Chicago, recently named by Advertising Age as Number 5 on their Agency A List. ScriptPhD.com was honored to speak with John Claxton, Creative Director of the Human Element campaign and author of the print ads and TV spots.

ScriptPhD.com: When Dow first came to you for this rebrand, what was their overarching objective?

John Claxton: A new CEO, Andrew Liveris, was just establishing himself and his philosophy at Dow. He had put a great deal of thought and effort behind his mantra for the company—making Dow the most respected chemical company in the world—and was anxious to make it a reality.

SPhD: How much of the Human Element and its message of empowerment did they have input in?

JC: As a creative idea, the Human Element came from us. But their eagerness to redefine the company and their clearly articulated business goals left no question about which direction to go in. Dow had carefully laid the foundation. We simply provided the creative idea to bring their vision to life.

SPhD: Take us through a couple of key steps of the creative development to help us conceptualize going from point zero (a blank slate, essentially) to the final product.

JC: One of the first steps was a creative meeting at our agency during the “pitch process.” I walked into the meeting with a new element for the Periodic Table. . . not carbon, hydrogen or oxygen, but the Human Element.

That pretty much put everything in motion. Including the Human Element on the Periodic Table of the Elements changed the way Dow looked at the world and the way the world looked at Dow.

Every creative decision we made from that point on was filtered through the lens of the Human Element, and that’s what took us down a very non-science approach to science advertising.

SPhD: Tell me a little about the strategy and aims of the written portion of the campaign (the copy).

JC: In terms of the strategy, we knew we wanted to find a “voice” for the campaign that lived at the other end of the spectrum from traditional science advertising.

There were three things that inspired the “voice” of the campaign we ultimately landed on. Science essays. The writing of E. O. Wilson. And contemporary American poetry.

SPhD: What was the biggest challenge for your team on this project?

JC: The television shoots are incredibly time-consuming (most of them a month or more) and span several continents.

SPhD: In retrospect, what surprised you the most about this campaign?

JC: We were completely surprised by the passionate response from people at all levels of society. From teachers to politicians to parents, people were so moved that they felt compelled to write to the company and express their feelings. The campaign struck a nerve in a way that we had never imagined.

SPhD: What do you feel makes branding science and technology a different or unique creative proposition?

JC: It is very difficult to make something abstract like science relevant to people, particularly in traditional media like television and print.

SPhD: What’s your favorite commercial or print ad of all time?

JC: I know this will seem like heresy, Jovana, but I really don’t study advertising. In fact, I don’t own a television. I read science essays. I study human behavior. I study and enjoy contemporary poetry.

We thank the wonderful, talented advertising team at Draftfcb Chicago, including Creative Director John Claxton and Communications Manager Joshua Dysart, for their cooperation and help in this installment of Selling Science Smartly.

~*ScriptPhD*~

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development.

Follow us on Twitter and our Facebook fan page. Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

]]>

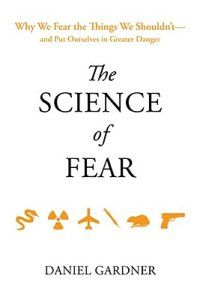

“First of all, let me assert my firm belief that the only thing we have to fear is fear itself—nameless, unreasoning, unjustified terror which paralyzes needed efforts to convert retreat into advance.” These inspiring words, borrowed from scribes Henry David Thoreau and Michel de Montaigne, were spoken by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt at his first inauguration during the only era more perilous than the one we currently face. But FDR had it easy. All he had to face was 25% unemployment and 2 million homeless Americans. We have, among other things, climate change, carcinogens, leaky breast implants, the obesity epidemic, the West Nile virus, SARS, avian/swine flu, flesh-eating disease, pedophiles, predators, herpes, satanic cults, mad cow disease, crack cocaine, and let’s not forget that paragon of Malthusian-like fatalism—terror. In his brilliant book The Science of Fear, journalist Daniel Gardner delves into the psychology and physiology of fear and the incendiary factors that drive it, including media, advertising, government, business and our own evolutionary mold. For our final blog post of 2009, ScriptPhD.com extends the science into a personal reflection, a discussion of why, despite there never having been a better time to be alive, we are more afraid than ever, and how we can turn a more rational leaf in the year 2010.

Prehistoric Predispositions and the Human Brain

Let’s talk about psychology for a moment. The psychology of fear, to be specific. Our minds largely evolved to cope with the “Environment of Evolutionary Adaptation”; Stone Age survival needs hard-wired into our brains to create a two-tiered system of conscious and subconscious thought. Elucidated by 2002 Nobel Prize winner in economics Daniel Kahneman, the systems are divided into the prehistoric System One (Gut) and System Two (Head). Gut is quick, evolutionary and designed to react to mortal threats, while Head is more modern, conscious thought capable of analyzing statistics and being rational. In a seminal 1974 paper published in the journal Science, Kahneman and his research partner Amos Tversky punctured the long-held belief that decision-making occurs via a Homo economicus (rational man) by proving that decisions are mostly made by the gut using three simple heuristics, or rules. The anchoring and adjustment heuristic (Anchoring Rule) involves grabbing hold of the nearest or most recent number when uncertain about a correct answer. This helps explain why the number 50,000 has been used to describe everything from how many predators are on the Internet in the 2000s to how many children were kidnapped by strangers every day in the 80s to the number of murders committed by Satanic cults in the 90s. The representativeness heuristic, or Rule of Typical Things, is our Gut judging things based on largely learned intuition. This explains why many predictions by experts are often as wrong as they are right. And why, despite being convinced they are not racist, Western societies perpetuate a dangerous stereotype of the non-white male. Finally, and most importantly, the availability heuristic, or Example rule, dictates that the easier it is to recall examples of something, the more common it must be. This is particularly sensitive to our memory formation and retention, particularly of violent or painful events, which were key to species survival in dangerous prehistoric times.