It has become compulsory for modern medical (or scientifically-relevant) shows to rely on a team of advisors and experts for maximal technical accuracy and verisimilitude on screen. Many of these shows have become so culturally embedded that they’ve changed people’s perceptions and influenced policy. Even the Gates Foundation has partnered with popular television shows to embed important storyline messages pertinent to public health, HIV prevention and infectious diseases. But this was not always the case. When Neal Baer joined ER as a young writer and simultaneous medical student, he became the first technical expert to be subsumed as an official part of a production team. His subsequent canon of work has reshaped the integration of socially relevant issues in television content, but has also ushered in an age of public health awareness in Hollywood, and outreach beyond it. Dr. Baer sat down with ScriptPhD to discuss how lessons from ER have fueled his public health efforts as a professor and founder of UCLA’s Global Media Center For Social Impact, including storytelling through public health metrics and leveraging digital technology for propelling action.

Neal Baer’s passion for social outreach and lending a voice to vulnerable and disadvantaged populations was embedded in his genetic code from a very young age. “My mother was a social activist from as long as I can remember. She worked for the ACLU for almost 45 years and she participated in and was arrested for the migrant workers’ grape boycott in the 60s. It had a true and deep impact on me that I saw her commitment to social justice. My father was a surgeon and was very committed to health care and healing. The two of them set my underlying drives and goals by their own example.” Indeed, his diverse interests and innate curiosity led Baer to study writing at Harvard and the American Film Institute and eventually, medicine at Harvard Medical School. Potentially presenting a professional dichotomy, it instead gave him the perfect niche — medical storytelling — that he parlayed into a critical role on the hit show ER.

During his seven-year run as medical advisor and writer on ER, Baer helped usher the show to indisputable influence and critical acclaim. Through the narration of important, germane storylines and communication of health messages that educated and resonated with viewers, ER‘s authenticity caught the attention of the health care community and inspired many television successors. “It had a really profound impact on me, that people learn from television, and we should be as accurate as possible,” Baer reflects. “[Viewers] believe it’s real, because we’re trying to make it look as real as possible. We’re responsible, I think. We can’t just hide behind the façade of: it’s just entertainment.” As show runner of Law & Order: SVU, Baer spearheaded a storyline about rape kit backlogs in New York City that led to a real-life push to clear 17,000 backlogged kits and established a foundation that will help other major US cities do the same. With the help of the CDC and USC’s prestigious Norman Lear Center, Baer launched Hollywood, Health and Society, which has become an indispensable and inexhaustible source of expert information for entertainment industry professionals looking to incorporate health storylines into their projects. In 2013, Baer co-founded the Global Media Center For Media Impact at UCLA’s School of Public Health, with the aim of addressing public health issues through a combination of storytelling and traditional scientific metrics.

Soda Politics

One of Baer’s seminal accomplishments at the helm of the Global Media Center was convincing public health activist Marion Nestle to write the book Soda Politics: Taking on Big Soda (And Winning). Nestle has a long and storied career of food and social policy work, including the seminal book Food Politics. Baer first took note of the nutritional and health impact soda was having on children in his pediatrics practice. “I was just really intrigued by the story of soda, and the power that a product can have on billions of people, and make billions of dollars, where the product is something that one can easily live without,” he says. That story, as told in Soda Politics, is a powerful indictment on the deleterious contribution of soda to the United States’ obesity crisis, environmental damage and political exploitation of sugar producers, among others. More importantly, it’s an anthology of the history of dubious marketing strategies, insider lobbying power and subversive “goodwill” campaigns employed by Big Soda to broaden brand loyalty.

Even more than a public health cautionary tale, Soda Politics is a case study in the power of activism and persistent advocacy. According to a New York Times expose, the drop in soda consumption represents the “single biggest change in the American diet in the last decade.” Nestle meticulously details the exhaustive, persistent and unyielding efforts that have collectively chipped away at the Big Soda hegemony: highly successful soda taxes that have curbed consumption and obesity rates in Mexico, public health efforts to curb soda access in schools and in advertising that specifically targets young children, and emotion-based messaging that has increased public awareness of the deleterious effects of soda and shifted preference towards healthier options, notably water. And as soda companies are inevitably shifting advertising and sales strategy towards , as well as underdeveloped nations that lack access to clean water, the lessons outlined in the narrative of Soda Politics, which will soon be adapted into a documentary, can be implemented on a global scale.

ActionLab Initiative

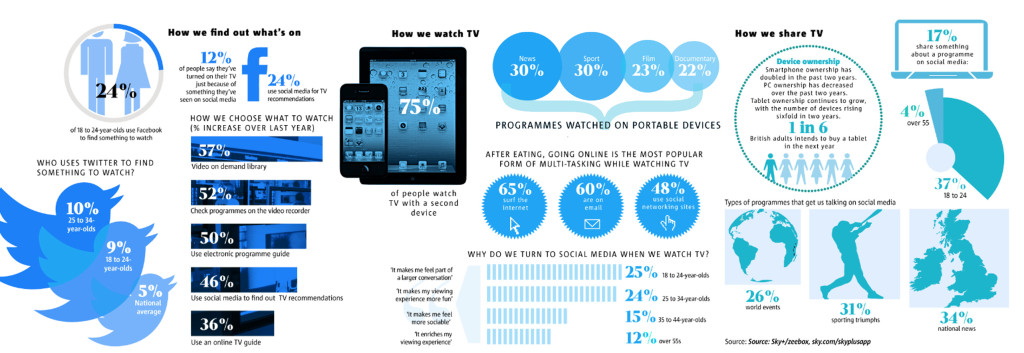

Few technological advancements have had an impact on television consumption and creation like the evolution of digital transmedia and social networking. The (fast-crumbling) traditional model of television was linear: content was produced and broadcast by a select conglomerate of powerful broadcast networks, and somewhat less-powerful cable networks, for direct viewer consumption, measured by demographic ratings and advertising revenue. This model has been disrupted by web-based content streaming such as YouTube, Netflix, Hulu and Amazon, which, in conjunction with fractionated networks, will soon displace traditional TV watching altogether. At the same time, this shifting media landscape has burgeoned a powerful new dynamic among the public: engagement. On-demand content has not only broadened access to high-quality storytelling platforms, but also provides more diverse opportunities to tackle socially relevant issues. This is buoyed by the increased role of social media as an entertainment vector. It raises awareness of TV programs (and influences Hollywood content). But it also fosters intimate, influential and symbiotic conversation alongside the very content it promotes. Enter ActionLab.

One of the critical pillars of the Global Media Center at UCLA, ActionLab hopes to bridge the gap between popular media and social change on topics of critical importance. People will often find inspiration from watching a show, reading a book or even an important public advertising campaign, and be compelled to action. However, they don’t have the resources to translate that desire for action into direct results. “We first designed ActionLab about five or six years ago, because I saw the power that the shows were having – people were inspired, but they just didn’t know what to do,” says Baer. “It’s like catching lightning in a bottle.” As a pilot program, the site will offer pragmatic, interactive steps that people can implement to change their lives, families and communities. ActionLab offers personalized campaigns centered around specific inspirational projects Baer has been involved in, such as the Soda Politics book, the If You Build It documentary and a collaboration with New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristof on his book/documentary A Path Appears. As the initiative expands, however, more entertainment and media content will be tailored towards specific issues, such as wellness, female empowerment in poor countries, eradicating poverty and community-building.

“We are story-driven animals. We collect our thoughts and our memories in story bites,” Baer notes. “We’re always going to be telling stories. We just have new tools with which to tell them and share them. And new tools where we can take the inspiration from them and ignite action.”

Baer joined ScriptPhD.com for an exclusive interview, where he discussed how his medical education and the wide-reaching impact of ER influenced his social activism, why he feels multi-media and cross-platform storytelling are critical for the future of entertainment, and his future endeavors in bridging creative platforms and social engagement.

ScriptPhD: Your path to entertainment is an unusual one – not too many Harvard Medical School graduates go on to produce and write for some of the most impactful television shows in entertainment history. Did you always have this dual interest in medicine and creative pursuits?

Neal Baer: I started out as a writer, and went to Harvard as a graduate student in sociology, [where] I started making documentary films because I wanted to make culture instead of studying it from the ivory tower. So, I got to take a documentary course, and it’s come full circle because my mentor Ed Pinchas made his last film called “One Cut, One Life” recently and I was a producer, before his demise from leukemia. That sent me to film school at the American Film Institute in Los Angeles as a directing fellow, which then sent me to write and direct an ABC after-school special called “Private Affairs” and to work on the show China Beach. I got cold feet [about the entertainment industry] and applied to medical school. I was always interested in medicine. My father was a surgeon, and I realized that a lot of the [television] work I was doing was medically oriented. So I went to Harvard Medical School thinking that I was going to become a pediatrician. Little did I know that my childhood friend John Wells, who had hired me on China Beach, would [also] hire me on “ER” by sending me the script, originally written by Michael Crichton in 1969, and dormant for 25 years until it was discovered in a trunk owned by Steven Spielberg. [Wells] asked me what I thought of the script and I said “It’s like my life only it’s outdated.” I gave him notes on how to update it, and I ultimately became one of the first doctor-writers on television with ER, which set that trend of having doctors on the show to bring verisimilitude.

SPhD: From the series launch in 1994 through 2000, you wrote 19 episodes and created the medical storylines for 150 episodes. This work ran parallel to your own medical education as a medical student, and subsequently an intern and resident. How did the two go hand in hand?

NB: I started writing on ER when I was still a fourth year medical student going back and forth to finish up at Harvard Medical School, and my internship at Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles over six years. And I was very passionate about bringing public health messages to the work that I was doing because I saw the impact that television can have on the audience, particularly the large numbers of people that were watching ER back then.

I was Noah Wylie’s character Dr. Carter. He was a third year [medical student], I was a fourth year. So I was a little bit ahead of him, and I was able to capture what it was like to be the low person on the totem pole and to reflect his struggles through many of the things my friends and I had gone through or were going through. Some of my favorite episodes we did were really drawn on things that actually happened. A friend of mine was sequestered away from the operating table but the surgeons were playing a game of world capitals. And she knew the capital of Zaire, when no one else did, so she was allowed to join the operating table [because of that]. So [we used] that same circumstance for Dr. Carter in an episode. Like you wouldn’t know those things, you had to live through them, and that was the freshness that ER brought. It wasn’t what you think doctors do or how they act but truly what goes on in real life, and a lot of that came from my experience.

SPhD: Do you feel like the storylines that you were creating for the show were germane both to things happening socially as well as reflective of the experience of a young doctor in that time period?

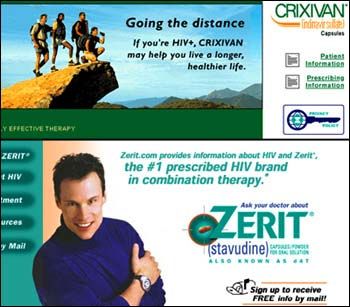

NB: Absolutely. We talked to opinion leaders, we had story nights with doctors, residents and nurses. I would talk to people like Donna Shalala, who was the head of the Department of Health and Human Safetey. I asked the then-head of the National Institutes of Health Harold Varmus, a Nobel Prize winner, “What topics should we do?” And he said “Teen alcohol abuse.” So that is when we had Emile Hirsch do a two-episode arc directly because of that advice. Donna Shalala suggested doing a story about elderly patients sharing perscriptions because they couldn’t afford them and the terrible outcomes that were happening. So we were really able to draw on opinion leaders and also what people were dealing with [at that time] in society: PPOs, all the new things that were happening with medical care in the country, and then on an individual basis, we were struggling with new genetics, new tests, we were the first show to have a lead character who was HIV-positive, and the triple cocktail therapy didn’t even come out until 1996. So we were able to be path-breaking in terms of digging into social issues that had medical relevance. We had seen that on other shows, but not to the extent that ER delved in.

SPhD: One of the legacies of a show like ER is how ahead of its time it was with many prescient storylines and issues that it tackled that are relevant to this very day. Are there any that you look back on that stand out to you in that regard as favorites?

NB: I really like the storyline we did with Julianna Margulies’s character [Nurse Carole Hathaway] when she opened up a clinic in the ER to deal with health issues that just weren’t being addressed, like cervical cancer in Southeast Asian populations and dealing with gaps in care that existed, particularly for poor people in this country, and they still do. Emergency rooms [treating people] is not the best way efficiently, economically or really humanely. It’s great to have good ERs, but that’s not where good preventative health care starts. The ethical dilemmas that we raised in an episode I wrote called “Who’s Happy Now?” involving George Clooney’s character [Dr. Doug Ross] treating a minor child who had advanced cystic fibrosis and wanted to be allowed to die. That issue has come up over and over again and there’s a very different view now about letting young people decide their own fate if they have the cognitive ability, as opposed to doing whatever their parents want done.

SPhD: You’ve had an Appointment at UCLA since 2013 at the Fielding School of Global Health as one of the co-founders of the Global Media Center for Social Impact, with extremely lofty ambitions at the intersection of entertainment, social outreach, technology and public health. Tell me a bit about that partnership and how you decided on an academic appointment at this time in your life.

NB: Well, I’m still doing TV. I just finished a three-year stint running the CBS series Under the Dome, which was a small-scale parable about global climate change. While I was doing that, I took this adjunct professorship at UCLA because I felt that there’s a lot we don’t know about how people take stories, learn them, use them, and I wanted to understand that more. I wanted to have a base to do more work in this area of understanding how storytelling can promote public health, both domestically and globally. Our mission at the Global Media Center for Social Impact (GMI) is to draw on both traditional storytelling modes like film, documentaries, music, and innovative or ‘new’ or transmedia approaches like Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, graphic novels and even cell phones to promote and tell stories that engage and inspire people and that can make a difference in their lives.

SPhD: One of the first major initiatives is a very important book “Soda Politics” by the public health food expert Dr. Marion Nestle. You were actually partially responsible for convincing her to write this book. Why this topic and why is it so critical right now?

NB: I went to Marion Nestle because I was convinced after having read a number of studies, particularly those by Kelly Brownell (who is now Dean of Public Policy at Duke University), that sugar-sweetened sodas are the number one contributor to childhood obesity. Just [recently], in the New York Times, they chronicled a new study that showed that obesity is still on the rise. That entails horrible costs, both emotionally and physically for individuals across this country. It’s very expensive to treat Type II diabetes, and it has terrible consequences – retinal blindness, kidney failure and heart disease. So, I was very concerned about this issue, seeing large numbers of kids coming into Children’s Hospital with Type II diabetes when I was a resident, which we had never seen before. I told Marion Nestle about my concerns because I know she’s always been an advocate for reducing the intake and consumption of soda, so I got [her] research funds from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. What’s really interesting is the data on soda consumption really aren’t readily available and you have to pay for it. The USDA used to provide it, but advocates for the soda industry pushed to not make that data easily available. I [also] helped design an e-book, with over 50 actionable steps that you can take to take soda out of the home, schools and community.

SPhD: How has social media engagement via our phones and computers, directly alongside television watching, changed the metric for viewing popularity, content development and key outreach issues that you’re tackling with your ActionLab initiative?

NB: ActionLab does what we weren’t [previously] able to do, because we have the web platforms now to direct people in multi-directional ways. When I first started on ER in 1994, television and media were uni-directional endeavors. We provided the content, and the viewer consumed it. Now, with Twitter [as an example], we’ve moved from a uni-directional to a multi-directional approach. People are responding, we are responding back to them as the content creators, they’re giving us ideas, they’re telling us what they like, what they don’t like, what works, what doesn’t. And it’s reshaping the content, so it’s this very dynamic process now that didn’t exist in the past. We were really sheltered from public opinion. Now, public opinion can drive what we do and we have to be very careful to put on some filters, because we can’t listen to every single thing that is said, of course. But we do look at what people are saying and we do connect with them in ways they never had access to us before.

This multi-directional approach is not just actors and writers and directors discussing their work on social media, but it’s using all of the tools of the internet to build a new way of storytelling. Now, anyone can do their own shows and it’s very inexpensive. There are all kinds of YouTube shows on now that are watched by many people. It’s a kind of Wild West, where anything goes and I think that’s very exciting. It’s changed the whole world of how we consume media. I [wrote] an episode of ER 20 years ago with George Clooney, where he saved a young boy in a water tunnel, that was watched by 48 million people at once. One out of six Americans. That will never happen again. So, we had a different kind of impact. But now, the media landscape is fractured, and we don’t have anywhere near that kind of audience, and we never will again. It’s a much more democratic and open world than it used to be, and I don’t even think we know what the repercussions of that will be.

SPhD: If you had a wish list, what are some other issues or global obstacles that you’d love to see the entertainment world (and media) tackle more than they do?

NB: In terms of specifics, we really need to talk about civic engagement, and we need to tell stories about how [it] can change the world, not only in micro-ways, say like Habitat For Humanity or programs that make us feel better when we do something to help others, but in a macro policy-driven way, like asking how we are going to provide compulsory secondary education around the world, particularly for girls. How do we instate that? How do we take on child marriage and encourage countries, maybe even through economic boycotts, to raise the age of child marriage, a problem that we know places girls in terrible situations, often with no chance of ever making a good living, much less getting out of poverty. So, we need to think both macroly and microly in terms of our storytelling. We need to think about how to use the internet and crowdsourcing for public policy and social change. How can we amalgamate individuals to support [these issues]? We certainly have the tools now, with Facebook, Twitter and Instagram, and our friends and social networks, to spread the word – and a very good way to spread the word is through short stories.

SPhD: You’ve enjoyed a storied career, and achieved the pinnacle of success in two very competitive and difficult industries. What drives Dr. Neal Baer now, at this stage of your life?

NB: Well, I keep thinking about new and innovative ways to use trans media. How do I use graphic novels in Africa to tell the story of HIV and prevention? How do we use cell phones to tell very short stories that can motivate people to go and get tested? Innovative financing to pay for very expensive drugs around the world? So, I’m very much interested in how storytelling gets the word out, because stories don’t just change minds, they change hearts. Stories tickle our emotions in ways that I think we don’t fully understand yet. And I really want to learn more about that. I want to know about what I call the “epigenetics of storytelling.” I’m writing a book about that, looking into research that [uncovers] how stories actually change our brain and how do we use that knowledge to tell better stories.

Neal Baer, MD is a television writer and producer behind hit shows China Beach, ER, Law & Order SVU, Under The Dome, and others. He is a graduate of Harvard University Medical School and completed a pediatrics internship at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles. A former co-chair of USC’s Norman Lear Center Hollywood, Health and Society, Dr. Baer is the founder of the Global Media Center for Social Impact at the Fielding School of Global Health at UCLA.

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development. Follow us on Twitter and Facebook. Subscribe to our podcast on SoundCloud or iTunes.

On February 28, 1998, the revered British medical journal The Lancet published a brief paper by then-high profile but controversial gastroenterologist Andrew Wakefield that claimed to have linked the MMR (measles, mumps and rubella) vaccine with regressive autism and inflammation of the colon in a small case number of children. A subsequent paper published four years later claimed to have isolated the strain of attenuated measles virus used in the MMR vaccine in the colons of autistic children through a polymerase chain reaction (PCR amplification). The effect on vaccination rates in the UK was immediate, with MMR vaccinations reaching a record low in 2003/2004, and parts of London losing herd immunity with vaccination rates of 62%. 15 American states currently have immunization rates below the recommended 90% threshold. Wakefield was eventually exposed as a scientific fraud and an opportunist trying to cash in on people’s fears with ‘alternative clinics’ and pre-planned a ‘safe’ vaccine of his own before the Lancet paper was ever published. Even the 12 children in his study turned out to have been selectively referred by parents convinced of a link between the MMR vaccine and their children’s autism. The original Lancet paper was retracted and Wakefield was stripped of his medical license. By that point, irreparable damage had been done that may take decades to reverse.

How could a single fraudulent scientific paper, unable to be replicated or validated by the medical community, cause such widespread panic? How could it influence legions of otherwise rational parents to not vaccinate their children against devastating, preventable diseases, at a cost of millions of dollars in treatment and worse yet, unnecessary child fatalities? And why, despite all evidence to the contrary, have people remained adamant in their beliefs that vaccines are responsible for harming otherwise healthy children, whether through autism or other insidious side effects? In his brilliant, timely, meticulously-researched book The Panic Virus, author Seth Mnookin disseminates the aggregate effect of media coverage, echo chamber information exchange, cognitive biases and the desperate anguish of autism parents as fuel for the recent anti-vaccine movement. In doing so, he retraces the triumphs and missteps in the history of vaccines, examines the social impact of rejecting the scientific method in a more broad perspective, and ways that this current utterly preventable public health crisis can be avoided in future scenarios. A review of The Panic Virus, an enthusiastic ScriptPhD.com Editor’s Selection, follows below.

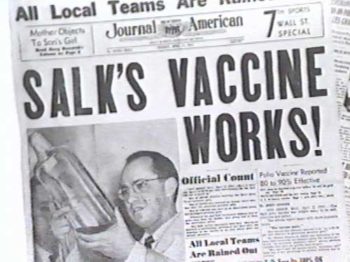

Such fervent controversy over inoculating young children for communicable diseases might have seemed unimaginable to the pre-vaccine generations. It wasn’t long ago, Mnookin chronicles, that death and suffering at the hands of diseases like polio and small pox were the accepted norm. In 18th Century Europe, for example, 400,000 people per year regularly died of small pox, and it caused one third of all cases of blindness. So desperate were people to avoid the illnesses’ ravages, that crude, rudimentary inoculation methods were employed, even at the high risk of death, to achieve life-long immunity. A 1916 polio outbreak in New York City, with fatality rates between 20 and 25 percent, frayed nerves and public health infrastructure to the point of near-anarchy. As the disease waxed and waned in outbreaks throughout the decades that followed, distraught parents had no idea about how to protect their children, who were often far more susceptible to fatality than adults. By the time Jonas Salk’s polio vaccine breakthrough was announced as “safe, effective and potent” on April 12, 1955, pandemonium broke out. “Air raid sirens were set off,” Mnookin writes. “Traffic lights blinked red; churches’ bells rang; grown men and women wept; schoolchildren observed a moment of silence.” Salk’s discovery was hailed as “one of the greatest events in the history of medicine.”

Mnookin doesn’t let scientists off the hook where vaccines are concerned, however, and rightfully so. Starting around World War II, with advances such as the cowpox and polio vaccines, along with the dawning of the Antibiotics Age, eradicating death and suffering from communicable diseases and bacterial infections, a hubris and sense of superiority began to creep into the scientific establishment, with dangerous consequences. Fearing the threat of biological warfare during World War II, a 1941 hastily-constructed US military campaign to vaccinate all US troops against yellow fever resulted in batches contaminated with Hepatitis B, resulting in 300,000 infections and 60 deaths. The first iteration of Salk’s polio vaccine was only 60-90% effective before being perfected and eventually replaced by the more effective Sabin vaccine. Furthermore, dozens of children who had received doses from the first batch of vaccines were paralyzed or killed due to contaminated vaccines that had failed safety tests. In 1976, buoyed by the death of a soldier from a flu virus that bore striking genetic similarity to the 1918 Spanish flu epidemic strain, President Gerald Ford instituted a nation-wide mass vaccination initiative against a “swine flu” epidemic. Unfortunately, although 40 million Americans were vaccinated in three months, 500 developed symptoms of Guillain-Barré syndrome (30 died), seven times higher than would normally be expected as a rare side effect of vaccination. Many people feel that the scars of the 1976 fiasco have incurred a permanent distrust of the medical establishment and have haunted public health influenza immunization efforts to this day.

These black marks on the otherwise miraculous, life-saving history of vaccine development not only instilled a gradual mistrust in public health officials, but laid the groundwork for the incendiary autism-vaccine scandal. The only missing components were a proper context of panic, a snake oil salesman and a compliant media willing to spread his erroneous message.

Enter the autism epidemic and Andrew Wakefield’s hoax. Because this seminal event had such a profound effect on the formation and proliferation of the current anti-vaccine movement, it is chronicled in far greater detail than our introduction above. From precursor incidents that ripened the potential for coercion to the Wakefield’s shoddy methodology and the naive medical community that took him at his word, Mnookin weaves through this case with well-researched scientific facts, interesting interviews and logic. A large chunk of the book is ultimately devoted to the psychology of what the anti-vaccine movement really is: a cognitive bias and a willingness to stay adamant in the belief that vaccines cause harm despite all evidence to the contrary. “If you assume,” he writes, “as I had, that human beings are fundamentally logical creatures, this obsessive preoccupation with a theory that has for all intents and purposes been disproved is hard to fathom. But when it comes to decisions around emotionally charged topics, logic often takes a back seat to a set of unconscious mechanisms that convince us that it is our feelings about a situation and not the facts that represent the truth.”

Given this blog’s objective to cover science and technology in entertainment and media, it would be disingenuous to write about the anti-vaccine movement without recognizing the implicit role played by the media and entertainment industries in exacerbating the polemic. By lending a voice to the anti-vaccine argument, even in a subtle manner or in a journalistic attempt to “be fair to the other side,” over time, an echo chamber of lies turned into an inferno. In 1982, an hour-long NBC documentary called DPT: Vaccine Roulette aired, overemphasizing rare side effects in babies from vaccinations to a nation of alarmed parents and completely undermining their benefits. It was a propaganda piece, but an important hallmark for what would come later. A 2008 episode of the popular ABC hit show Eli Stone irresponsibly aired anti-vaccination propaganda involving a lawyer questioning a pharmaceutical company that manufactures vaccines due to the even then-debunked link to autism. For several recent years, actress and Playboy bunny Jenny McCarthy (who is given an entire chapter by Mnookin) became a tireless advocate against vaccinations, believing that they gave her son autism. She didn’t have any scientific proof for this, but was nevertheless given a platform by everyone from Larry King on CNN to a fawning Oprah Winfrey.

As it turns out, McCarthy’s son never even had autism, but rather a very rare and treatable neurological disorder. In a self-penned editorial for the Chicago Sun-Times, she has officially retroactively denied her anti-vaccine stance, and says she simply wants “more research on their effectiveness.” An extremely sympathetic 2014 eight-page Washington Post magazine article profile of prominent anti-vaccine activist Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. (who believes in the link between vaccines and autism) repeated his talking points numerous times throughout. This, among an endless cycle of interviews and appearances by defiant anti-vaccine proponents, given equal air time side-by-side with frustrated scientists, as if both positions were somehow viable, and worthy of journalistic debate. Once the worm was out of the can, no amount of rational discourse could temper the visceral antipathy that had been created. This is irresponsible, dangerous and flat-out wrong. When the public is confused about an esoteric issue pertaining to science, medicine or technology, influencers in the public eye cannot perpetuate misinformation.

Despite the unanimous medical repudiation of Wakefield’s fraudulent methods and conclusions and the retraction of his Lancet paper, an irreversible and insidious myth had begun permeating, first among the autism community, then spreading to proponents of organic and holistic approaches to health and finally, to mainstream society. In the aftermath of the controversy, epidemiological studies debunking the autism-vaccination “link,” combined with a growing disease crisis, have forced the largest US-based autism advocacy organization to reverse its stance and fully endorse vaccination to a still-divided community. Wakefield remains more defiant than ever, insisting to this day that his research was valid, attempting to sue the British journalism outlet that funded the inquiry into his fraud and peddling holistic treatments for autism as well as his “alternative” vaccine. Sadly, the public health ramifications have nothing short of disastrous, with a dangerous recurrence of several major childhood diseases.

A few examples of the many systemic casualties of the anti-vaccination movement (many occurring just since the publication of Mnookin’s book):

•A summary from the American Medical Association about the nascence of the measles crisis in 2011, when the US saw more measles cases than it had in 15 years

•Immunization rates falling so low that schools in some communities are being forced to terminate personal exemption waivers and, in some cases, legally mandated immunization for public school attendance

•California’s worst whooping cough epidemic in 70 years.

•Most recently, a measles outbreak at Disneyland, resulting in 26 cases spread across four states, after an unvaccinated woman visited the theme park

•Anti-vaccine hysteria has spread to Europe, which has had a measles rise of 348% from 2013 to 2014 (and growing), along with an alarming resurgence of pertussis

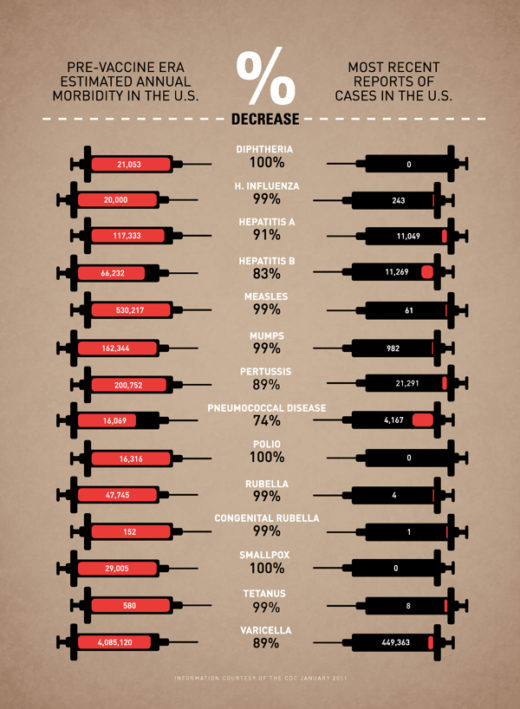

The scientific evidence that vaccines work is indisputable, and as the below infographic summarizes, their impact on morbidity from communicable diseases is miraculous. Sadly, now that the anti-vaccine movement has streamlined into the general population, anxious parents are conflicted as to whether vaccinating is the right choice for their children. We must start by going back to the basics of what a vaccine actually is and how it works. Next, we must reiterate the critical importance that maintaining herd immunity above 92-95% plays in protecting not only those too young or immunocompromised to be vaccinated, but even fully vaccinated populations. If all else fails, try emailing skeptical friends and family a clever graphic cartoon that breaks down digestible vaccine facts. Simply put: getting vaccinated is not a personal choice, it’s a selfish and dangerous choice.

The Panic Virus is first and foremost an incredibly entertaining, well-written narrative of the dawn of an anti-vaccine phenomenon which has reached a critical mass. It is also an important case study and cautionary tale about how we process and disseminate information in the age of the Internet and access to instant information. It is also an indictment on a trigger-happy, ratings-driven, sensationalist media that reports “news” as they interpret it first, and bother to check for facts later. In the case of the anti-vaccine movement of the last few years, the media fueled the fire that Andrew Wakefield started, and once a gaggle of angry, sympathetic parents was released, it was difficult (if-near impossible) to undo the damage. This type of journalism, Mnookin writes, “gives credence to the belief that we can intuit our way through all the various decisions we need to make in our lives and it validates the notion that our feelings are a more reliable barometer of reality than the facts.” Sadly, the autism-vaccine panic movement is not an outlying incident, but rather a disconcerting emblem of a growing anti-science agenda. The UN just released its most dire and alarming report ever issued on man-made climate change impacts, warning that temperature changes and industrial pollution will affect not just the environment, extreme weather events and coastal cities, but even the stability of our global economy itself. Immediate rebuttals from an influential lobbying group tried to undermine the majority of the scientists’ findings. So toxic is the corporate and political resistance to any kind of mitigating action, that some feel we need a technological or political miracle to stave off a certain environmental crisis. At a time when physicists are serious debate on evolution versus creationism and thousands of public schools across the United States use taxpayer funds to teach creationism in the classroom.

Mnookin’s book is an important resource and conversation starter for scientists, researchers and frustrated physicians as they carve out talking points and communication strategies to establish a dialogue with the public at large. When young parents have questions about vaccines (no matter how erroneous or ill-informed), pediatricians should already have materials for engaging in a positive, thoughtful discussion with them. When scientists and researchers encounter anti-science proclivities or subversive efforts to undermine their advocacy for a pressing issue, they should be armed with powerful, articulate communicators — ready and willing to deliberate in the media and convey factual information in an accessible way. When Jenny McCarthy and a gaggle of new-age holistic herbologists were peddling their “mommy instincts” and conspiracy theories against vaccines, far too many scientists and physicians simply thought it was beneath them to even engage in a discussion about something whose certainty and proof of concept was beyond reproach. Now, the newest polling suggests that nothing will change an anti-vaxxer’s mind, not even factual reasoning. Going forward, regardless of the issue at hand, this type of response can never happen again. The cost of complacency or arrogance is nothing short of life or death.

The Panic Virus by Seth Mnookin is currently available on paperback and Kindle wherever books are sold. For further reading on how to deal with the complexities of the anti-vaccine movement aftermath, we suggest the recent book On Immunity: An Inoculation by Northwestern University lecturer Eula Bliss.

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development. Follow us on Twitter and Facebook. Subscribe to our podcast on SoundCloud or iTunes.

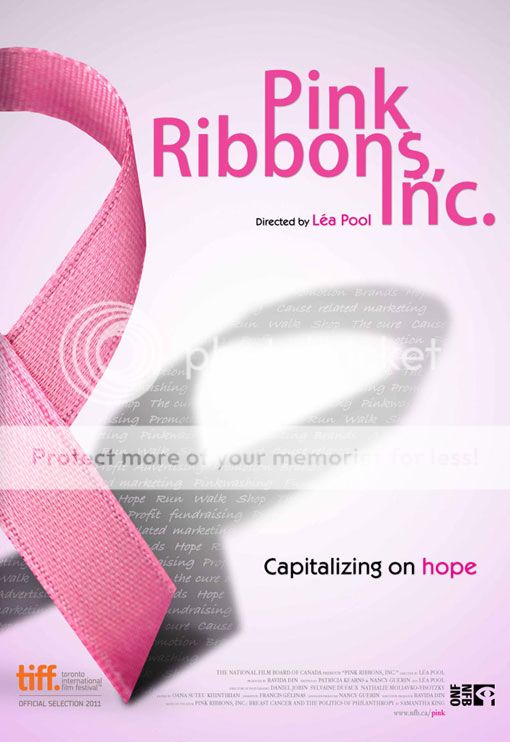

Earlier this year, the Susan G. Komen Foundation made headlines around the world after their politically-charged decision to cut funding for breast cancer screening at Planned Parenthood caused outrage and negatively impacted donations. Despite reversing the decision and apologizing, many people in the health care and fund raising community feel that the aftermath of the controversy still dogs the foundation. Indeed, Advertising Age literally referred to it as a PR crisis. If all of this sounds more like spin for a brand rather than a charity working towards the cure of a devastating illness, it’s not far from the truth. Susan G. Komen For the Cure, Avon Walk For Breast Cancer and the Revlon Run/Walk For Women represent a triumvirate hegemony in the “pink ribbon” fundraising domain. Over time, their initial breast cancer awareness movement (and everything the pink ribbon stood for symbolically) has moved from activism to pure consumerism. The new documentary Pink Ribbons, Inc. deftly and devastatingly examines the rise of corporate culture in breast cancer fundraising. Who is really profiting from these pink ribbon campaigns, brands or people with the disease? How has the positional messaging of these “pink ribbon” events impacted the women who are actually facing the illness? And finally, has motivation for profit driven the very same companies whose products cause cancer to benefit from the disease? ScriptPhD.com’s Selling Science Smartly advertising series continues with a review of Pink Ribbons, Inc..

“We used to march in the streets. Now you’re supposed to run for a cure, or walk for a cure, or jump for a cure, or whatever it is,” states Barbara Ehrenreich, breast cancer survivor and author of Welcome to Cancerland, in the opening minutes of the documentary Pink Ribbons, Inc. Directed by Canadian filmmaker Lea Pool and based on the book Pink Ribbons, Inc.: Breast Cancer and the Politics of Philosophy by Samantha King, the documentary features in-depth interviews with leading authors, experts, activists and medical professionals. It also includes an important look at the leading players in breast cancer fundraising and marketing. The production crew filmed a number of prominent fundraising events across North America, using the upbeat festivities (where some didn’t even visibly show the word ‘cancer’) as the backdrop for exploring the “pinkwashing” of breast cancer through marketing, advertising and slick gimmicks. At the same time, showcasing well-meaning, enthusiastic walkers, runners and fundraisers is a double-edged sword and was handled with the appropriate sensitivity by the filmmakers. Pool wanted to “make sure we showed the difference between the participants, and their courage and will to do something positive, and the businesses that use these events to promote their products to make money.”

Often lost amidst the pomp and circumstance of these bright pink feel-good galas is that the origins of the pink ribbon are quite inauspicious. The original pink ribbon wasn’t even pink. It was a salmon-colored cloth ribbon made by breast cancer activist Charlotte Haley as part of a grass roots organization she called Peach Corps. From a kitchen counter mail-in operation, Haley’s vision grew to hundreds of thousands of supporters, so much so that it caught the attention of Estee Lauder founder Evelyn Lauder. The company wanted to buy the peach ribbon from Haley, who refused, so they simply rebranded breast cancer to a comforting, reassuring, non-threatening color: bright pink. And before our very eyes, a stroke of marketing genius was born.

As the pink ribbon movement took hold of the fundraising community, the money started to spill over into mainstream advertising, adorning everything from the food we eat to the clothes we wear, all under the auspices of philanthropy. In theory, people should feel great about buying products that return some of their profits for such a great cause. In practice, many of these campaigns simply throw a bright pink cloak over false, if not cynical, advertising. Take Yoplait’s yearly “Save Lids to Save Lives” campaign:

For every lid you save from a Yoplait yogurt (and mail in, using a $0.44 stamp, mind you!), they will donate 10 cents to breast cancer research. If you ate three yogurts per day for fourth months, you will have raised a grand total of $36 for breast cancer research, but spent more on stamps and in environmental shipping waste. Not as impressive when you break it down, eh?

A recent American Express campaign called “Every Dollar Counts” pledged that every purchase during a four month period would incur a one cent donation to breast cancer research. Unfortunately, they never quantified donations commensurate to spending, so that meant whether you charged a pack of gum or a big screen TV to your AmEx, they would donate a penny. The breast cancer community was so outraged by this hubris, they staged a successful campaign to rescind the ads. The fact is, the above examples demonstrate that pink ribbons have become an industry, with demographics and talking points, just like everything else. Pinkwashing campaigns tend to target middle class, ultra-feminine white women. Why? Because they are typical targets that move the products these industries are trying to sell. Take the NFL’s recent pink screening campaign. Well-meaning or not, it came amidst a series of crimes and violence by NFL players, some of which was domestic in nature. One can imagine that players adorned in hot pink gear would have been a smart way to mollify its rather impressive female fanbase.

As Ehrenreich states in the documentary, the collective effect of this marketing has been to soften breast cancer into a pretty, pink and feminine disease. Nothing too scary, nothing too controversial. Just enough to keep raising money that goes… somewhere. Take a look at the recent chipper television campaign for the Breast Cancer Centre of Australia:

While some of the breast cancer-related branding and pink sponsorships mislead through good intentions, others are a dangerous bold-faced lie. Some of the very companies that sponsor fundraising events and make money off of pink revenue either make deleterious products linked to cancer or stand to profit from treatment of it. Revlon, sponsors of the Run/Walk for Women, are manufacturers of many cosmetics (searchable on the database Skin Deep) that are linked to cancer. The average woman puts on 12 cosmetics products per day, yet only 20% of all cosmetics have undergone FDA examination and safety testing. The pharmaceutical giant Astra Zeneca can’t seem to decide if it’s for or against cancer. They produce the anti-estrogen breast cancer drug Tamoxifen, yet also manufacture the pesticide atrazine (under the Swiss-based company Syngenta), which has been linked to cancer as an estrogen-boosting compound. Breast cancer history month (October) is nothing more than a PR stunt that was invented by a marketing expert at… drumroll please… Astra Zeneca! Their goal was to promote mammography as a powerful weapon in the war against breast cancer. But as the American arm of the largest chemical company in the world, the reality is that Astra Zeneca was and is benefiting from the very illness it was urging women to get screened for. Perhaps the most audacious example of them all is pharmaceutical giant Eli Lilly. Sponsors of cancer research and treatment, both in medicine and the community, Lilly produced the cancer and infertility causing DES (diethylstilbestrol), and currently manufactures rBGH, an artificial hormone given to cows to make them produce more milk. rBGH has been linked to breast cancer and a host of other health problems. These strong corporate links in many ways explain the uplifting, happy, sterile messaging behind the pink ribbon. Corporations are, quite bluntly, making money off of marketing cancer, so if they don’t put a smiley face on the disease, they will alienate their customers and the conglomerate businesses pouring money into these campaigns.

Juxtaposed with the uplifting, bombastic, bright pink backdrop of the various cancer fundraisers and rallies, Pink Ribbons, Inc. quietly profiles the IV League, an Austin, TX-based support group for metastatic breast cancer. The women meet on a regular basis to share stories, help each other cope and accept the rigors of the disease and realities of dying. Many of the group members interviewed found current breast cancer campaign marketing offensive, tastelessly positive and falsely empowering (“If you just get screened and get mammograms and eat healthy, breast cancer can’t happen to you!”). The group, which has lost 10 members last year alone, is among a large faction of cancer sufferers that feel left out in the pinkwashing tide of marketing campaigns. Highlighting that sometimes you do get cancer because of no explanation, and sometimes you won’t respond to any treatment is a downer. It’s not the kind of uplifting story that advertising campaigns are built around, leaving the women feeling as if they’re living alone with the fact that they are dying. “You’re the angel of death,” remarks IV Leaguer Jeanne Collins. “You’re the elephant in the room. And they’re learning to live and you’re learning to die.” By utilizing powerful messaging keywords like BATTLE, WAR and SURVIVOR, cancer foundations and brands are subliminally putting down those who didn’t survive. And there are many who don’t survive — someone dies of breast cancer every 69 seconds. Are they suggesting that people who died or didn’t respond to treatment simply didn’t try hard enough? One of the most poignant moments in the film was an IV League Stage 4 cancer patient, probably weeks or months from her death: “You can die in a perfectly healed state.”

Although Pink Ribbons, Inc. is a sobering polemic against the mindless trivialization of commercializing breast cancer and even misdirecting funds from where they can be most helpful, it is not a hopeless film. Far from projecting pessimism, the film showcases the tremendous willpower and manpower that these three-day walks engender. It is simply misdirected. If hundreds of thousands of women and men can be motivated to fundraise, walk, run and (in some cases) jump out of planes, the effort is absolutely there to stop breast cancer. “Do something besides worry to make a difference,” concludes Barbara Brenner. “We have enormous power, if only we’d use it.” Director Lea Pool hopes that the film will encourage people to “be more critical about our actions and stop thinking that by buying pink toilet paper we’re doing what needs to be done. I don’t want to say that we absolutely shouldn’t be raising money. We are just saying ‘Think before you pink.'”

Watch the trailer for Pink Ribbons, Inc. here:

Pink Ribbons, Inc. goes into wide release in theaters nationwide June 8, 2012 and was released on DVD in September of 2012.

~*ScriptPhD*~

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development.

Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

]]>

“It’s like a war. You don’t know whether you’re going to win the war. You don’t know if you’re going to survive the war. You don’t know if the project is going to survive the war.” The war? Cancer, still one of the leading causes of death despite 40 years passing since the National Cancer Act of 1971 catapulted Richard Nixon’s famous “War on Cancer.” The speaker of the above quote? A scientist at Genentech, a San Francisco-based biotechnology and pharmaceutical company, describing efforts to pursue a then-promising miracle treatment for breast cancer facing numerous obstacles, not the least of which was the patients’ rapid illness. If it sounds like a made-for-Hollywood story, it is. But I Want So Much To Live is no ordinary documentary. It was commissioned as an in-house documentary by Genentech, a rarity in the staid, secretive scientific corporate world. The production values and storytelling offer a tremendous template for Hollywood filmmakers, as science and biomedical content become even more pervasive in film. Finally, the inspirational story behind Herceptin, one of the most successful cancer treatments of all time, offers a testament and rare insight to the dedication and emotion that makes science work. Full story and review under the “continue reading” cut.

For biotechnology and pharmaceutical companies, it is the best of times, it is the worst of times. On the one hand, many people consider this a Golden Era of pharmaceutical discovery and innovation for certain illnesses like cancer. Others, such as HIV, receive poor grades for drug and vaccine development. Furthermore, the FDA recently passed much more stringent controls on drugs brought to market, leaving some to posit that this will have a negative impact on future pharmaceutical breakthroughs. And while a recent documentary chronicles some of the unhealthy profits of the pharmaceutical industry, the enormous cost of developing and bringing medicines to market is often gravely overlooked. Today, the pharmaceutical industry as a whole has one of the lowest favorability scores of any major industry, despite some impressive social contributions, partnerships and global health investments. Much of this public hostility simply comes down to the fact that people don’t know very much about the pharmaceutical industry, notoriously reluctant to publicize or reveal anything about their inner workings.

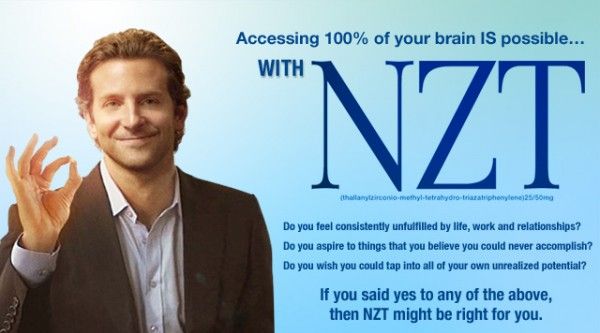

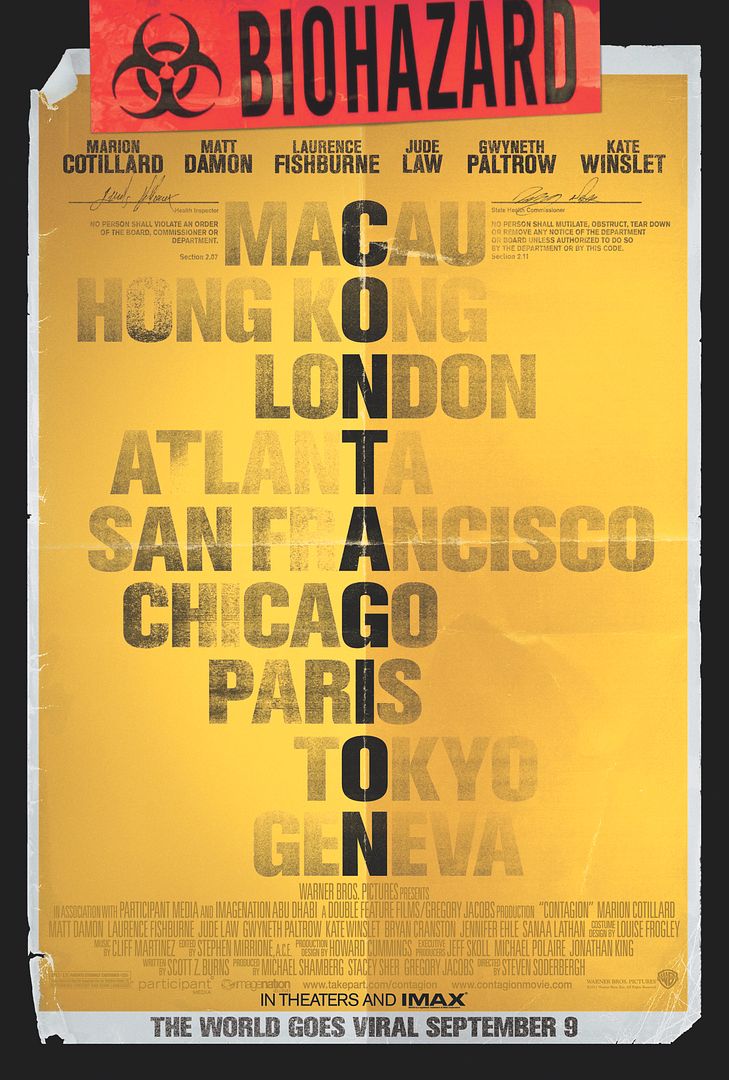

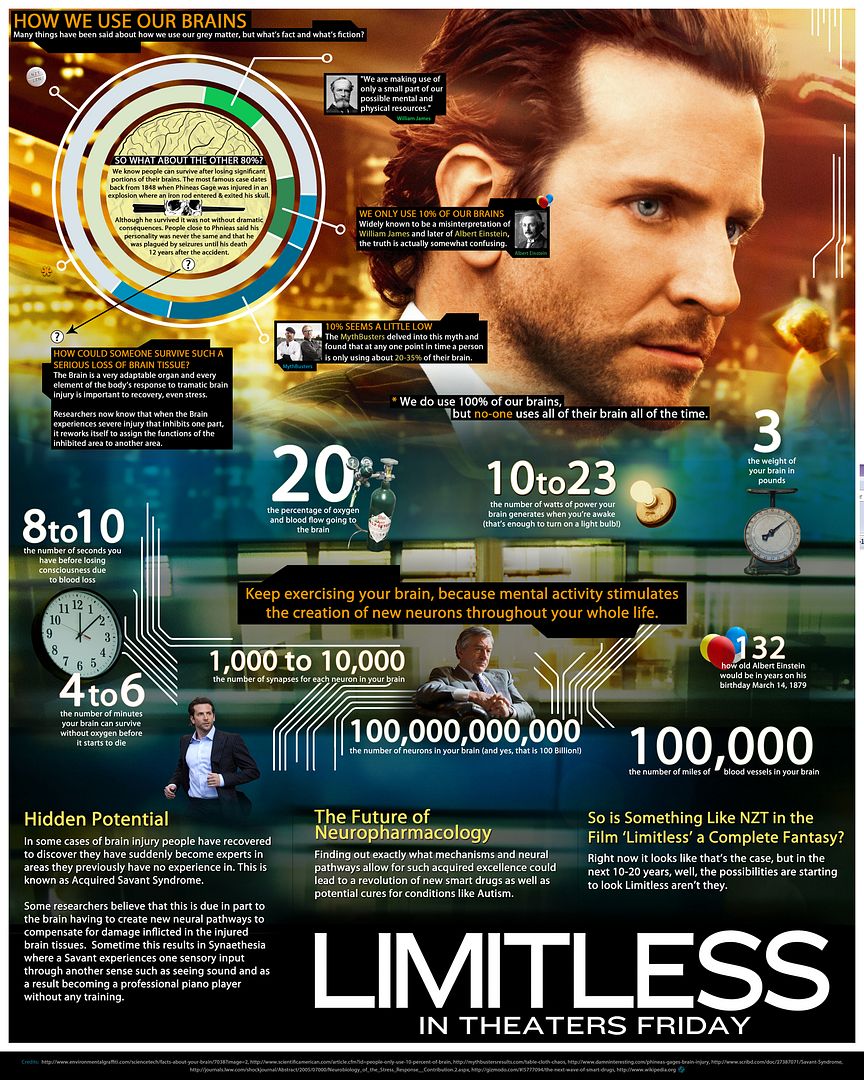

Science in Hollywood is experiencing no such crisis. In many ways, it is a golden age for science, technology and medicine in film, with more big-budget mainstream films exploring themes and content germane to 21st Century science than ever before. Last year alone, three smart hit movies broached the realities, hopes and anxiety of the technological times we live in, each in a very different way. The stylish and ambitious thriller Limitless explored the possibility of a limitless brain capacity through pharmacopeia, a magical pill that would maximize one’s intelligence and allow 100% brain function around the clock. Certainly echoing the credo of the modern pharmaceutical movement—there is a pill that can solve every problem, whether it’s been invented or not—Limitless fell slightly short in condemning (or even properly acknowledging) the impracticalities ethical irresponsibility of developing such a drug, especially in its ending. Stephen Soderbergh’s surgical and pinpoint-accurate epic Contagion gave audiences a spine-chilling, terrorizing purview into the medical and public health realities of a modern-day pandemic. But while it strove, and succeeded, in showcasing how government agencies, university labs and medical establishments would contend with and fight off such a global disaster, Contagion was never able to connect audiences emotionally either with the characters impacted by the pandemic or with the scientists battling it. No recent movie is a better example of delicate introspection and exposition than the brilliant, poignant, funny and difficult 50/50. On the heels of CNN pondering whether Hollywood could take on cancer came a film that did so with reality, grace and even humor. Partially because it was based on screenwriter Will Reiser’s own brush with cancer, 50/50 set aside the clinical as a secondary backdrop to examine the psychological.

Each of the films above has an important quality that is be an essential component to effective Hollywood science storytelling – scientific accuracy, emotional connection to the outside world and an overview of biomedical impact and innovation. We recently screened an industry documentary, filmed at the request of Genentech scientists, called I Want So Much To Live, that is an excellent blueprint for the way we’d like to see scientific stories portrayed in film. Best of all, it doesn’t sacrifice the human story for the technical one, nor the very real complex emotions that scientists, engineers and doctors feel when they develop and market potentially life-saving technology.

The miracle of Herceptin is really a decade-long journey that started in the labs of UCLA, moved to the pharmaceutical labs of San Francisco, endured countless obstacles, street riots and controversies to end up as one of the most revolutionary breakthroughs in breast cancer treatment research history. Advances in cancer insight always seem to come in evolutionary leaps. For example, the cellular mechanism of how normal cells become cancerous was unknown until Harold Varmus and Michael Bishop established the presence of retroviral oncogenes, genes that control cellular growth and replication. When either disrupted or turned on, these genes contribute to the transformation of normal cells into tumors. Other than the discovery of as an anti-estrogen treatment for breast cancers, relatively little new ground had been gained in fighting the disease. Scientists continued to be perplexed why some women were cured by chemotherapy, which tries to stop cancer cell division by attacking the most rapidly-dividing cells in the body, while others didn’t respond at all. It was not until the late 80s that scientists Alex Ullrich and Michael Shepherd (both featured in the film) discovered that about 20-30% of early-stage breast cancers express amplify a gene called HER-2, a protein embedded in the cell membrane that helps regulate cell growth and signaling. With the help of UCLA scientist Dennis Slamon, famously portrayed by Harry Connick, Jr. in a made-for-TV movie about the development of Herceptin, the scientists soon developed an anti-HER-2 antibody that significantly slowed tumor growth.

An early Phase I clinical trial was conducted simply to establish safety, with 20 volunteers. The lone survivor, still alive to this day, was given 10 weeks to live. Phase II trials honed in on dosage and establishing that the drug performed its intended effects. This time, out of 85 volunteers, 5 survived completely, not a bad result, but not enough for the FDA and the science community. The scientists took a huge risk for their Phase III study. They combined their anti-HER-2 antibody with current treatment. The results were astounding. Out of 450 patients, 50% survived — the highest ever success rate for metastatic cancer!

Think the story ends here? Think again. This is where it just begins to take more emotional twists and turns than a fictitious Hollywood script. Unlike many Hollywood productions, though, the human impact angle was shared equally between all the players in this evolving story, easily this documentary’s most powerful aspect. In order to test their Phase III trials of Herceptin (in concert with chemotherapy treatments available at that time), Genentech had to establish a highly controversial lottery system to pick those who would receive highly limited life-saving quantities of Herceptin, and those who would be categorized in the control studies, and thereby handed a death sentence. So controversial was the lottery system, that it engendered televised protests in the Bay Area, along with anguished pleas from dying patients—the documentary’s title is the first sentence of one such letter: “I want so much to live.” The scientists at Genentech were hardly immune to the weight of each decision, either. They were tormented over the fairness of the lottery system, producing enough high-quality treatment to pass the clinical trial, and even in keeping an unbiased eye on the science to save lives in the long run. Talking about the pressure of those days reduced one of the scientists to tears. And after all was said and done, the lone FDA scientist entrusted with the power to oversee the Herceptin study and green light its approval as a drug? She had just lost her mother to breast cancer. These intertwining fortunes are summarized by executive producer Christie Castro: “By definition, groups of people are imperfect. But those who worked on Herceptin proved that the complexity – indeed, the fantastic mess – that simply comes with being human can sometimes result in something truly worthwhile.”

One of the first patients to get the experimental Herceptin treatment prior to FDA approval, though not profiled in the movie, is flourishing well over a decade after being diagnosed with the most aggressive form of breast cancer. Stories like hers lie at the emotional heart of the I Want So Much To Live story (and Genentech’s motivation for continuing the controversial studies):

Herceptin was officially approved as a drug on September 22, 2000. On October 20, 2010, Herceptin was approved as an adjuvant (joint) treatment with current chemotheraphy drugs for the treatment of aggressive breast cancer. To date, the adjuvant therapy has had an impressive 58% success rate for a cancer that once carried an unlikely rate of survival for those afflicted.

Take a look at the trailer for I Want So Much To Live:

The powerful and well-crafted content of this documentary should serve as a valuable template for how the multi-faceted power of storytelling can be used across multiple industries. It smartly tells a gripping scientific story without either dumbing down the science or elevating it beyond a layperson’s understanding—a certain goal for the increasing amount of cinematic fare such as Contagion. It provides a functional breakdown of the enormous challenges and technical obstacles of the pharmaceutical drug development process. Like many other aspects of science, it is mysterious to the general public, out of their grasp and seemingly always occuring behind closed doors. Especially at a time when public perception of the pharmaceutical industry is at an all-time low, such transparency could strengthen reputations and increase business. “Corporations are,” executive producer Christine Castro reminds us, “groups of people who have ideas, ambitions, conflicts and dreams, and, at the end of the day, a desire to see their work result in something meaningful. That’s why we decided to take a creative chance and face the potential skepticism that a corporation would or could tell an unvarnished story about itself.”

Finally, the film develops a three-dimensional emotional tether to the three different sides impacted by the scientific process: scientists, the agencies that regulate them and society as a whole. There doesn’t always have to be a tacit bad guy, and sometimes, this protagonistic complexity makes for the best story of all. Holder, who started filming I Want So Much To Live around the same time that her late brother was diagnosed with a rare and virulent form of cancer, echoed our sentiment as she reflected on the process of making the film. It allowed her to discover “that science is a creative pursuit as well as a technical one; that science is beautiful and can be accessible; and that anyone, at any time, might have the idea that could one day save lives.”

We can only hope that the harmony of creativity, passion and emotion devoted to all sides of the drug discovery process within this film translates to more private and studio productions dealing with complex scientific and socio-technological issues.

ScriptPhD.com caught up with filmmaker Elizabeth Holder, who directed and produced I Want So Much To Live. Here are some of her thoughts on putting together this incredible story and interacting with the scientists and heroic patients that made it happen:

ScriptPhD.com: Can you tell me where the seeds of inspiration for the story of the drug Herceptin first arose, and what inspired you to tackle this material for your documentary?

Elizabeth Holder: The initial idea to make a documentary film about Herceptin came from executive producer Chris Castro, who upon joining Genentech in 2007 thought that the story would make a compelling documentary film. (She will have to share with you her experience.) I first heard about the project from a friend and began doing research on Herceptin and Genentech. I was excited to work on this film; excited to jump into and explore a new world. My first inspiration came from the people who were the story; the passionate men and women who faced adversity with courage and perseverance, never swaying from their pursuit, making difficult decisions laced with moral and ethical ramifications. I knew this story of individual and collective growth would resonate with many, and would be especially poignant to the employees of Genentech. (This at the time was the intended audience for the film.) When I began working on this film in 2008 I had no idea how personal this journey would become and how connected I would be to the people I would meet and the story I was going to tell.

While I was making the film, my younger brother David was battling cancer – a rare type of cancer for a 33 year old man. While I was meeting with scientists and learning about biotech and drug development for the movie, David was fighting the disease with everything science and medicine could offer. He wrote a blog about his journey, signing off each entry with the words “Plow On”. Each day, I would hope that the scientists would hurry up. Figure it out. But I learned firsthand that science is not a “hurry up” business and that many people are doing everything they can to find ways to stop cancer. My wish is that the film serves to inspire everyone who is on the frontlines in the battle against cancer, to encourage them to keep on fighting the good fight, no matter what, and even on a bad day, to Plow On.

SPhD: How willing were the patients and scientists to contribute to the project?

EH: As you can imagine, everyone, especially scientists, are skeptical. Some people took a bit more convincing than others, but once they started talking, the interviews, both on and off camera, were amazing.

I am grateful to the patients, scientists, activists, executives, and doctors for honestly and enthusiastically sharing their stories, perspective, and experience with me. I quickly became indebted to mentors and colleagues who diligently and without judgment explained and re-explained molecular biology and the drug development process to me. I hope the determination and delight in which they approach their work is reflected in the film.

SPhD: Any of your own preconceived notions that were shattered or altered throughout the making of this film?

EH: I discovered striking similarities between scientists and filmmakers which I did not expect to find. A research scientist and a filmmaker must each imagine an idea, convince others to recognize the value of funding the idea, and then prove the concept. Like many filmmakers, the scientists I met were impassioned about their work and showed great determination in the face of extraordinary odds. Like filmmaking, drug development takes a village. Before making this film I had no idea how many years and how many people it took to develop a drug; the process involves a huge collaborative effort between massive numbers of people in multiple organizations, in various countries.

It was incredible and amazing to me that the scientists would talk about “cells” and “exxons” and “nucleotides” as if they could actually be seen by the human eye. It was also inspiring to me that a scientist is committed enough to work on a research project for their whole career with the knowledge that they might not ever see an outcome in their lifetime. And finally, I was pleased to confirm (though not statistically proven) that a lot of really smart and accomplished people do not have perfectly clean desks.

SPhD: Within the movie, we get a real feel for the dichotomy between the emotional appeals of the desperately ill patients, the cautious, careful FDA scientists, and the Genentech researchers who want to make sure the product they introduce is safe for patients. Was this a thematic element you foresaw or that developed as you pieced the film together?

EH: I carefully planned out the film, yet also left room for new discoveries along the way. (I was constantly learning – from each filmed interview, from advisors, from books.) For each defining moment in the film I made sure to film at least three people talking about the same experience with different opinions. I wanted to make sure that the topic was covered from various perspectives so I could intercut interviews together. I knew that I was not going to use narration. I only wanted people who were part of the story to be telling the story; to engage the audience with their firsthand accounts. I wanted the audience to feel connected emotionally to each person in the film, to empathize with the person on screen even if they disagreed with their tactic and/or goal. Additionally, I knew I was going to use archival footage, photos and authentic documents to organically reveal the isolation and miscommunication, the unwitting partnerships, the building mistrust and the eventual coming together. When I first saw and read the pile of letters saved by Geoff, I knew that I would use it in the film. I carried a few of those letters with me to every interview and pulled them out when it felt right, asking people to read them and respond. The scene was assembled to show how incorrect assumptions lead to strife; to show how each person’s journey was critical to the whole story; and to show how those intertwining stories eventually became the framework for the work that is continuing today.

SPhD: What are your own thoughts on the lottery system that Genentech ultimately used to determine who would be eligible to participate in the Herceptin clinical trials?

EH: I see both sides of the issue, and don’t think there is an easy answer. When interviewing people for this film, I went into each interview with a clean slate, without having any pre-conceived agenda or opinion. It was critical that I empathized with each person and was able to tell the story though the objectives and needs of those who I interviewed, those who had direct experience. I needed to be able to fully see and feel the situation from their point of view. And, to me, judgment is only something that pulls us apart, not together. I am thankful I am in the documentary business and not in the business of making the kind of decisions that had to be made during that time. I am not sure what I would have done if someone I loved needed the drug before it was approved.

~*ScriptPhD*~

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development.

Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

]]>

As far back as last summer, when pilots for the current television season were floating around, a quirky sci-fi show for NBC called Awake caught our eye as the best of the lot. Camouflaged in a standard procedural cop show is an ambitious neuroscience concept—a man living in two simultaneous dream worlds, either of which (or neither of which) could be real. We got a look at the first four episodes of the show, which lay a nice foundation for the many thought-provoking questions that will be addressed. We review them here, as well as answering some questions of our own about the sleep science behind the show with UCLA sleep expert Dr. Alon Avidan.

Detective Michael Britten (Jason Isaacs) is a middle class police officer living in Los Angeles, with a lovely wife and teenage son, a virtual ‘everyman’ until an unspeakable tragedy—in the show’s opening moments—transform him into a paranormal dual existence. A violent car accident kills at least one member of his family, possibly both (the audience doesn’t yet know, and neither does Britten). Except instead of mourning the loss and moving on, Britten begins a bifurcated dream existence, where in one state, his wife Hannah (Laura Allen) is alive and his son Rex (Dylan Minnette) has perished, and as soon as he wakes up, the opposite is true. Complicating matters further is the mirroring of his lives on each end of this sleep-wake spectrum state. In his ‘single father’ widower existence, he is partnered with gruff police veteran Isaiah Freeman (Steve Harris), and works with no-nonsense therapist Dr. Judith Evans (Cherry Jones). In his other existence, mourning

the loss of his son with his wife, Britten’s Captain (Laura Innes) has partnered him with rookie Efrem Vega (Wilmer Valderama), as he works things through with kind, objective therapist Dr. John Lee (BD Wong).

Juggling two worlds might seem complicated (and exhausting) enough, but life for Detective Britten gets even more muddled. Soon sliding with regularity between his two new worlds, he takes various clues from one to solve crimes in the other, even as his behavior in both becomes more erratic and precarious. And while the pilot flawlessly establishes the landscape of Britten’s new reality, future episodes will slowly chip away at it, leaving the viewers with many unanswered questions and mysteries. Is Britten simply dreaming one of these worlds? If so, which is his ‘true’ reality? Is either? Could they both be a lucid dream? Could it be that both his wife and son died? And while later episodes can sometimes veer a bit too much into standard procedural fare, they also offer a thunderbolt of a plot point, suggesting that the car crash that took Britten’s family may have been no accident at all. Given how quickly the last truly ambitious network sci-fi drama (Heroes) veered into absurdity, the steady pacing and erudite plot development of Awake is an almost welcome relief.

We look forward to dreaming for many episodes to come.

Catch up with what you may have missed with this extended trailer:

The sleep science behind the thought-provoking concept of Awake excited us a lot, but we wanted to get deeper answers to some of our most basic questions about the neuroscience of sleep, and just what it is that Michael Britten might be suffering from. To do so, ScriptPhD.com sat down with Dr. Alon Yosefian Avidan, the Director of the Sleep Disorders Laboratory at UCLA’s Department of Neurology.

ScriptPhD.com: Dr. Avidan, for people reading this that may not know very much at all about sleep science, can you give us a brief layperson’s overview of what the scientific consensus is on what sleep is for, exactly?

Alon Avidan: There is no answer. We don’t understand the central reason for why we need sleep. But we know one thing—we can’t do without it. There are about 13 theories that help explain why we sleep. The theories range from needing it to have better memory akin to letting your computer organize files in its sleep mode, so the brain is doing that same thing in your sleep; organizing thoughts, memories and allowing space for new ones to be formed. Another theory is that sleep has a rejuvenating function, essentially for repair, for better immune function. There are other theories that sleep is a hibernation period during which you don’t really need to eat or look for food and it’s a way for you to reserve your energy. This is probably, evolutionarily speaking, back when humans were foraging and needing to conserve energy. There are some theories that sleep is a way for us to synchronize our bodily functions with the Earth. There are really not that many things that we humans are capable of doing during the night, and this is a time for us to synchronize our biological rhythms with that of the Earth.

SPhD: So regardless of which of these theories is true, extreme sleep deprivation has really bad consequences.

AA: Absolutely. When exposed to extreme sleep deprivation, laboratory animals, rats in particular, don’t survive for more than two weeks. They begin to have skin changes, ulcers and they eventually die. In humans, we have situations where people don’t sleep enough. There is a very rare condition called fatal familial insomnia, a condition where patients lose the ability to sleep, and the patient rarely survives beyond a year, maybe six months. But we do know that there are very acute and very chronic consequences that we can observe very quickly [in sleep-deprived patients], including memory problems, planning, and problems with cognitive functions. The chronic issues include inability to regulate food intake, so people end up gaining weight, people end up at risk for diseases that include diabetes, heart disease. And we know that for patients who have primary sleep disorders such as sleep apnea, narcolepsy, insomnia or others, their life expectancy is lower compared to

patients in the same age group.

SPhD: Well, turning to some of the sleep issues in Awake, our main character, Michael Britten, vacillates between two different sleep states, both of which function as his reality, in order to cope with the loss of his wife, son or possibly both. How much do we in fact use our subconscious as a coping mechanism for the traumatic things that happen to us in our lives?

AA: That’s a very interesting point. We know that people who are depressed spend a lot of time in bed, they tend to spend a lot of time sleeping, but their quality of sleep is disrupted. And perhaps it is a coping mechanism for them not to deal with the true conflicts or trauma that are occurring in their lives. What’s very interesting is that in those patients, when they do sleep, sleep is very disrupted. The quality of sleep related to depression or anxiety is really bad. They have arousals, they have awakenings, the duration is short, and the quality of sleep is very light. They often wake up and feel as if they haven’t really slept.

SPhD: What about the dream aspect of sleep in this patient sub-population?

AA: Dreams are when healthy individuals reach the REM cycle (which you know is when we dream). You can have dreams in non-REM cycles as well. What’s interesting is that patients who have post-traumatic stress disorder or anxiety, their dreams are frightening. They’re usually nightmares. Studies show that in many patients who have a very profound trauma like 9/11 survivors in New York City, there was an epidemic of nightmares and stressful sleep experience. Dreams are not normal in patients who have psychiatric disorders, and they are more dramatic and more intense dreams.

SPhD: In the show, Mr. Britten takes clues from one sleep state to solve his crimes in another sleep state (either of which he considers a reality). One of his therapists warns him that doing this is incredibly dangerous because his “unconscious is unreliable.” What do you think the therapist meant by that?

AA: So what’s likely happening to him clinically is that he’s unable to distinguish between sleep and wakefulness. And what is being advised is be more careful not to rely on facts that may be occurring in dreams or wakefulness, because he is not aware which state this is arising from.

SPhD: Is there something to that piece of advice? What about people who regularly swear by premonitions or things they “see” in their dreams?

AA: Clinically, we really don’t see that very often. We don’t see patients relaying a sense of reality between sleep and wakefulness. There is a situation that is neither a sleep state, nor wakefulness, but a combination of the two—the patient has lost sense of what is real and what isn’t. Dissociative fugue disorder is a rare psychiatric disorder where the patient loses their sense of reality, their sense of identity. And it does have something to do with sleep because it’s one of those mixtures of sleep and wakefulness when the patient is unsure of whether they were asleep or awake. It involves extensive memory loss, usually into the wakefulness period, and the person just doesn’t have the capacity to determine what is real and what is fiction.