It has become compulsory for modern medical (or scientifically-relevant) shows to rely on a team of advisors and experts for maximal technical accuracy and verisimilitude on screen. Many of these shows have become so culturally embedded that they’ve changed people’s perceptions and influenced policy. Even the Gates Foundation has partnered with popular television shows to embed important storyline messages pertinent to public health, HIV prevention and infectious diseases. But this was not always the case. When Neal Baer joined ER as a young writer and simultaneous medical student, he became the first technical expert to be subsumed as an official part of a production team. His subsequent canon of work has reshaped the integration of socially relevant issues in television content, but has also ushered in an age of public health awareness in Hollywood, and outreach beyond it. Dr. Baer sat down with ScriptPhD to discuss how lessons from ER have fueled his public health efforts as a professor and founder of UCLA’s Global Media Center For Social Impact, including storytelling through public health metrics and leveraging digital technology for propelling action.

Neal Baer’s passion for social outreach and lending a voice to vulnerable and disadvantaged populations was embedded in his genetic code from a very young age. “My mother was a social activist from as long as I can remember. She worked for the ACLU for almost 45 years and she participated in and was arrested for the migrant workers’ grape boycott in the 60s. It had a true and deep impact on me that I saw her commitment to social justice. My father was a surgeon and was very committed to health care and healing. The two of them set my underlying drives and goals by their own example.” Indeed, his diverse interests and innate curiosity led Baer to study writing at Harvard and the American Film Institute and eventually, medicine at Harvard Medical School. Potentially presenting a professional dichotomy, it instead gave him the perfect niche — medical storytelling — that he parlayed into a critical role on the hit show ER.

During his seven-year run as medical advisor and writer on ER, Baer helped usher the show to indisputable influence and critical acclaim. Through the narration of important, germane storylines and communication of health messages that educated and resonated with viewers, ER‘s authenticity caught the attention of the health care community and inspired many television successors. “It had a really profound impact on me, that people learn from television, and we should be as accurate as possible,” Baer reflects. “[Viewers] believe it’s real, because we’re trying to make it look as real as possible. We’re responsible, I think. We can’t just hide behind the façade of: it’s just entertainment.” As show runner of Law & Order: SVU, Baer spearheaded a storyline about rape kit backlogs in New York City that led to a real-life push to clear 17,000 backlogged kits and established a foundation that will help other major US cities do the same. With the help of the CDC and USC’s prestigious Norman Lear Center, Baer launched Hollywood, Health and Society, which has become an indispensable and inexhaustible source of expert information for entertainment industry professionals looking to incorporate health storylines into their projects. In 2013, Baer co-founded the Global Media Center For Media Impact at UCLA’s School of Public Health, with the aim of addressing public health issues through a combination of storytelling and traditional scientific metrics.

Soda Politics

One of Baer’s seminal accomplishments at the helm of the Global Media Center was convincing public health activist Marion Nestle to write the book Soda Politics: Taking on Big Soda (And Winning). Nestle has a long and storied career of food and social policy work, including the seminal book Food Politics. Baer first took note of the nutritional and health impact soda was having on children in his pediatrics practice. “I was just really intrigued by the story of soda, and the power that a product can have on billions of people, and make billions of dollars, where the product is something that one can easily live without,” he says. That story, as told in Soda Politics, is a powerful indictment on the deleterious contribution of soda to the United States’ obesity crisis, environmental damage and political exploitation of sugar producers, among others. More importantly, it’s an anthology of the history of dubious marketing strategies, insider lobbying power and subversive “goodwill” campaigns employed by Big Soda to broaden brand loyalty.

Even more than a public health cautionary tale, Soda Politics is a case study in the power of activism and persistent advocacy. According to a New York Times expose, the drop in soda consumption represents the “single biggest change in the American diet in the last decade.” Nestle meticulously details the exhaustive, persistent and unyielding efforts that have collectively chipped away at the Big Soda hegemony: highly successful soda taxes that have curbed consumption and obesity rates in Mexico, public health efforts to curb soda access in schools and in advertising that specifically targets young children, and emotion-based messaging that has increased public awareness of the deleterious effects of soda and shifted preference towards healthier options, notably water. And as soda companies are inevitably shifting advertising and sales strategy towards , as well as underdeveloped nations that lack access to clean water, the lessons outlined in the narrative of Soda Politics, which will soon be adapted into a documentary, can be implemented on a global scale.

ActionLab Initiative

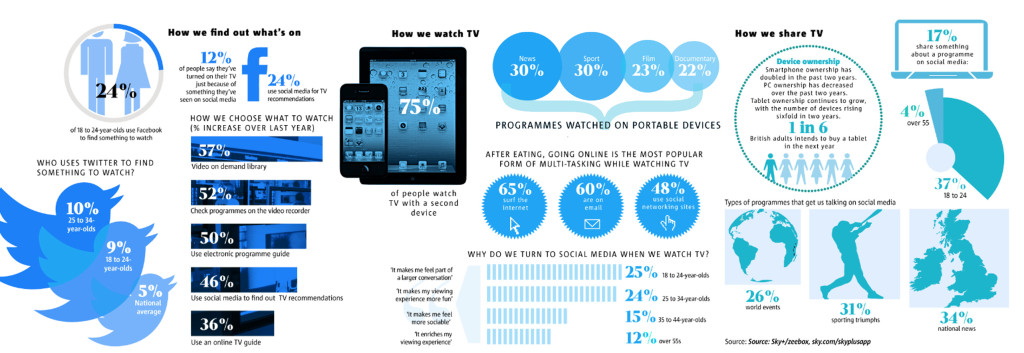

Few technological advancements have had an impact on television consumption and creation like the evolution of digital transmedia and social networking. The (fast-crumbling) traditional model of television was linear: content was produced and broadcast by a select conglomerate of powerful broadcast networks, and somewhat less-powerful cable networks, for direct viewer consumption, measured by demographic ratings and advertising revenue. This model has been disrupted by web-based content streaming such as YouTube, Netflix, Hulu and Amazon, which, in conjunction with fractionated networks, will soon displace traditional TV watching altogether. At the same time, this shifting media landscape has burgeoned a powerful new dynamic among the public: engagement. On-demand content has not only broadened access to high-quality storytelling platforms, but also provides more diverse opportunities to tackle socially relevant issues. This is buoyed by the increased role of social media as an entertainment vector. It raises awareness of TV programs (and influences Hollywood content). But it also fosters intimate, influential and symbiotic conversation alongside the very content it promotes. Enter ActionLab.

One of the critical pillars of the Global Media Center at UCLA, ActionLab hopes to bridge the gap between popular media and social change on topics of critical importance. People will often find inspiration from watching a show, reading a book or even an important public advertising campaign, and be compelled to action. However, they don’t have the resources to translate that desire for action into direct results. “We first designed ActionLab about five or six years ago, because I saw the power that the shows were having – people were inspired, but they just didn’t know what to do,” says Baer. “It’s like catching lightning in a bottle.” As a pilot program, the site will offer pragmatic, interactive steps that people can implement to change their lives, families and communities. ActionLab offers personalized campaigns centered around specific inspirational projects Baer has been involved in, such as the Soda Politics book, the If You Build It documentary and a collaboration with New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristof on his book/documentary A Path Appears. As the initiative expands, however, more entertainment and media content will be tailored towards specific issues, such as wellness, female empowerment in poor countries, eradicating poverty and community-building.

“We are story-driven animals. We collect our thoughts and our memories in story bites,” Baer notes. “We’re always going to be telling stories. We just have new tools with which to tell them and share them. And new tools where we can take the inspiration from them and ignite action.”

Baer joined ScriptPhD.com for an exclusive interview, where he discussed how his medical education and the wide-reaching impact of ER influenced his social activism, why he feels multi-media and cross-platform storytelling are critical for the future of entertainment, and his future endeavors in bridging creative platforms and social engagement.

ScriptPhD: Your path to entertainment is an unusual one – not too many Harvard Medical School graduates go on to produce and write for some of the most impactful television shows in entertainment history. Did you always have this dual interest in medicine and creative pursuits?

Neal Baer: I started out as a writer, and went to Harvard as a graduate student in sociology, [where] I started making documentary films because I wanted to make culture instead of studying it from the ivory tower. So, I got to take a documentary course, and it’s come full circle because my mentor Ed Pinchas made his last film called “One Cut, One Life” recently and I was a producer, before his demise from leukemia. That sent me to film school at the American Film Institute in Los Angeles as a directing fellow, which then sent me to write and direct an ABC after-school special called “Private Affairs” and to work on the show China Beach. I got cold feet [about the entertainment industry] and applied to medical school. I was always interested in medicine. My father was a surgeon, and I realized that a lot of the [television] work I was doing was medically oriented. So I went to Harvard Medical School thinking that I was going to become a pediatrician. Little did I know that my childhood friend John Wells, who had hired me on China Beach, would [also] hire me on “ER” by sending me the script, originally written by Michael Crichton in 1969, and dormant for 25 years until it was discovered in a trunk owned by Steven Spielberg. [Wells] asked me what I thought of the script and I said “It’s like my life only it’s outdated.” I gave him notes on how to update it, and I ultimately became one of the first doctor-writers on television with ER, which set that trend of having doctors on the show to bring verisimilitude.

SPhD: From the series launch in 1994 through 2000, you wrote 19 episodes and created the medical storylines for 150 episodes. This work ran parallel to your own medical education as a medical student, and subsequently an intern and resident. How did the two go hand in hand?

NB: I started writing on ER when I was still a fourth year medical student going back and forth to finish up at Harvard Medical School, and my internship at Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles over six years. And I was very passionate about bringing public health messages to the work that I was doing because I saw the impact that television can have on the audience, particularly the large numbers of people that were watching ER back then.

I was Noah Wylie’s character Dr. Carter. He was a third year [medical student], I was a fourth year. So I was a little bit ahead of him, and I was able to capture what it was like to be the low person on the totem pole and to reflect his struggles through many of the things my friends and I had gone through or were going through. Some of my favorite episodes we did were really drawn on things that actually happened. A friend of mine was sequestered away from the operating table but the surgeons were playing a game of world capitals. And she knew the capital of Zaire, when no one else did, so she was allowed to join the operating table [because of that]. So [we used] that same circumstance for Dr. Carter in an episode. Like you wouldn’t know those things, you had to live through them, and that was the freshness that ER brought. It wasn’t what you think doctors do or how they act but truly what goes on in real life, and a lot of that came from my experience.

SPhD: Do you feel like the storylines that you were creating for the show were germane both to things happening socially as well as reflective of the experience of a young doctor in that time period?

NB: Absolutely. We talked to opinion leaders, we had story nights with doctors, residents and nurses. I would talk to people like Donna Shalala, who was the head of the Department of Health and Human Safetey. I asked the then-head of the National Institutes of Health Harold Varmus, a Nobel Prize winner, “What topics should we do?” And he said “Teen alcohol abuse.” So that is when we had Emile Hirsch do a two-episode arc directly because of that advice. Donna Shalala suggested doing a story about elderly patients sharing perscriptions because they couldn’t afford them and the terrible outcomes that were happening. So we were really able to draw on opinion leaders and also what people were dealing with [at that time] in society: PPOs, all the new things that were happening with medical care in the country, and then on an individual basis, we were struggling with new genetics, new tests, we were the first show to have a lead character who was HIV-positive, and the triple cocktail therapy didn’t even come out until 1996. So we were able to be path-breaking in terms of digging into social issues that had medical relevance. We had seen that on other shows, but not to the extent that ER delved in.

SPhD: One of the legacies of a show like ER is how ahead of its time it was with many prescient storylines and issues that it tackled that are relevant to this very day. Are there any that you look back on that stand out to you in that regard as favorites?

NB: I really like the storyline we did with Julianna Margulies’s character [Nurse Carole Hathaway] when she opened up a clinic in the ER to deal with health issues that just weren’t being addressed, like cervical cancer in Southeast Asian populations and dealing with gaps in care that existed, particularly for poor people in this country, and they still do. Emergency rooms [treating people] is not the best way efficiently, economically or really humanely. It’s great to have good ERs, but that’s not where good preventative health care starts. The ethical dilemmas that we raised in an episode I wrote called “Who’s Happy Now?” involving George Clooney’s character [Dr. Doug Ross] treating a minor child who had advanced cystic fibrosis and wanted to be allowed to die. That issue has come up over and over again and there’s a very different view now about letting young people decide their own fate if they have the cognitive ability, as opposed to doing whatever their parents want done.

SPhD: You’ve had an Appointment at UCLA since 2013 at the Fielding School of Global Health as one of the co-founders of the Global Media Center for Social Impact, with extremely lofty ambitions at the intersection of entertainment, social outreach, technology and public health. Tell me a bit about that partnership and how you decided on an academic appointment at this time in your life.

NB: Well, I’m still doing TV. I just finished a three-year stint running the CBS series Under the Dome, which was a small-scale parable about global climate change. While I was doing that, I took this adjunct professorship at UCLA because I felt that there’s a lot we don’t know about how people take stories, learn them, use them, and I wanted to understand that more. I wanted to have a base to do more work in this area of understanding how storytelling can promote public health, both domestically and globally. Our mission at the Global Media Center for Social Impact (GMI) is to draw on both traditional storytelling modes like film, documentaries, music, and innovative or ‘new’ or transmedia approaches like Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, graphic novels and even cell phones to promote and tell stories that engage and inspire people and that can make a difference in their lives.

SPhD: One of the first major initiatives is a very important book “Soda Politics” by the public health food expert Dr. Marion Nestle. You were actually partially responsible for convincing her to write this book. Why this topic and why is it so critical right now?

NB: I went to Marion Nestle because I was convinced after having read a number of studies, particularly those by Kelly Brownell (who is now Dean of Public Policy at Duke University), that sugar-sweetened sodas are the number one contributor to childhood obesity. Just [recently], in the New York Times, they chronicled a new study that showed that obesity is still on the rise. That entails horrible costs, both emotionally and physically for individuals across this country. It’s very expensive to treat Type II diabetes, and it has terrible consequences – retinal blindness, kidney failure and heart disease. So, I was very concerned about this issue, seeing large numbers of kids coming into Children’s Hospital with Type II diabetes when I was a resident, which we had never seen before. I told Marion Nestle about my concerns because I know she’s always been an advocate for reducing the intake and consumption of soda, so I got [her] research funds from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. What’s really interesting is the data on soda consumption really aren’t readily available and you have to pay for it. The USDA used to provide it, but advocates for the soda industry pushed to not make that data easily available. I [also] helped design an e-book, with over 50 actionable steps that you can take to take soda out of the home, schools and community.

SPhD: How has social media engagement via our phones and computers, directly alongside television watching, changed the metric for viewing popularity, content development and key outreach issues that you’re tackling with your ActionLab initiative?

NB: ActionLab does what we weren’t [previously] able to do, because we have the web platforms now to direct people in multi-directional ways. When I first started on ER in 1994, television and media were uni-directional endeavors. We provided the content, and the viewer consumed it. Now, with Twitter [as an example], we’ve moved from a uni-directional to a multi-directional approach. People are responding, we are responding back to them as the content creators, they’re giving us ideas, they’re telling us what they like, what they don’t like, what works, what doesn’t. And it’s reshaping the content, so it’s this very dynamic process now that didn’t exist in the past. We were really sheltered from public opinion. Now, public opinion can drive what we do and we have to be very careful to put on some filters, because we can’t listen to every single thing that is said, of course. But we do look at what people are saying and we do connect with them in ways they never had access to us before.

This multi-directional approach is not just actors and writers and directors discussing their work on social media, but it’s using all of the tools of the internet to build a new way of storytelling. Now, anyone can do their own shows and it’s very inexpensive. There are all kinds of YouTube shows on now that are watched by many people. It’s a kind of Wild West, where anything goes and I think that’s very exciting. It’s changed the whole world of how we consume media. I [wrote] an episode of ER 20 years ago with George Clooney, where he saved a young boy in a water tunnel, that was watched by 48 million people at once. One out of six Americans. That will never happen again. So, we had a different kind of impact. But now, the media landscape is fractured, and we don’t have anywhere near that kind of audience, and we never will again. It’s a much more democratic and open world than it used to be, and I don’t even think we know what the repercussions of that will be.

SPhD: If you had a wish list, what are some other issues or global obstacles that you’d love to see the entertainment world (and media) tackle more than they do?

NB: In terms of specifics, we really need to talk about civic engagement, and we need to tell stories about how [it] can change the world, not only in micro-ways, say like Habitat For Humanity or programs that make us feel better when we do something to help others, but in a macro policy-driven way, like asking how we are going to provide compulsory secondary education around the world, particularly for girls. How do we instate that? How do we take on child marriage and encourage countries, maybe even through economic boycotts, to raise the age of child marriage, a problem that we know places girls in terrible situations, often with no chance of ever making a good living, much less getting out of poverty. So, we need to think both macroly and microly in terms of our storytelling. We need to think about how to use the internet and crowdsourcing for public policy and social change. How can we amalgamate individuals to support [these issues]? We certainly have the tools now, with Facebook, Twitter and Instagram, and our friends and social networks, to spread the word – and a very good way to spread the word is through short stories.

SPhD: You’ve enjoyed a storied career, and achieved the pinnacle of success in two very competitive and difficult industries. What drives Dr. Neal Baer now, at this stage of your life?

NB: Well, I keep thinking about new and innovative ways to use trans media. How do I use graphic novels in Africa to tell the story of HIV and prevention? How do we use cell phones to tell very short stories that can motivate people to go and get tested? Innovative financing to pay for very expensive drugs around the world? So, I’m very much interested in how storytelling gets the word out, because stories don’t just change minds, they change hearts. Stories tickle our emotions in ways that I think we don’t fully understand yet. And I really want to learn more about that. I want to know about what I call the “epigenetics of storytelling.” I’m writing a book about that, looking into research that [uncovers] how stories actually change our brain and how do we use that knowledge to tell better stories.

Neal Baer, MD is a television writer and producer behind hit shows China Beach, ER, Law & Order SVU, Under The Dome, and others. He is a graduate of Harvard University Medical School and completed a pediatrics internship at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles. A former co-chair of USC’s Norman Lear Center Hollywood, Health and Society, Dr. Baer is the founder of the Global Media Center for Social Impact at the Fielding School of Global Health at UCLA.

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development. Follow us on Twitter and Facebook. Subscribe to our podcast on SoundCloud or iTunes.

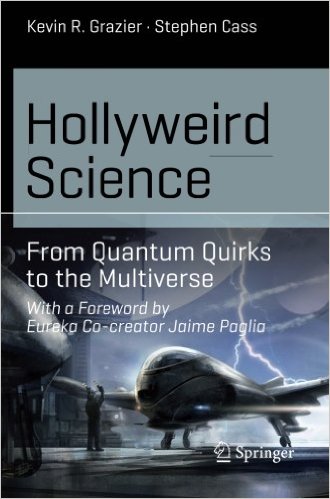

Dr. Kevin Grazier has made a career of studying intergalactic planetary formation, and, over the last few years, helping Hollywood writers integrate physics smartly into storylines for popular TV shows like Battlestar Galactica, Eureka, Defiance and the blockbuster film Gravity. His latest book, Hollyweird Science: From Quantum Quirks to the Multiverse traverses delightfully through the science-entertainment duality as it first breaks down the portrayal of science in movies and television, grounding the audience in screenplay lexicon, then elucidates a panoply of physics and astronomy principles through the lens of storylines, superpowers and sci-fi magic. With the help of notable science journalist Stephen Cass, Hollyweird Science is accessible to the layperson sci-fi fan wishing to learn more about science, a professional scientist wanting to apply their knowledge to higher-order examples from TV and film or Hollywood writers and producers of future science-based materials. From case studies, to in-depth interviews to breaking down the Universe and its phenomena one superhero and far-away galaxy at a time, this first volume of an eventual trilogy is the essential foundation towards understanding how science is integrated into a story and ensuring that future TV shows and movies do so more accurately than ever before. Full ScriptPhD review and podcast with author and science advisor Dr. Grazier below.

Most people who watch movies and TV shows never went to film school. They are not familiar with the intricacies of three-act structure, tropes, conceits and MacGuffins that are the skeletal framework of a standard storytelling toolkit. Yet no genre is more rooted in and dependent on setup and buying into a payoff than sci-fi and films conceptualized in scientific logic. Many, if not most, critiques of science in entertainment don’t fully acknowledge that integrating abstruse science/technology with the complex constraints of time, length, character development and screenplay format is incredibly demanding. Hollyweird Science does point out some egregious examples of “information pollution” and the “Hollywood Curriculum Cycle” – the perpetuation bad, if not fictitious, science. But after grounding the reader in a primer of the fundamental building blocks of movie-making and TV structure, not only is there a more positive, forgiving tone in breaking down the history of the sci-fi canon (some of which predicted many of the technological gadgets we enjoy today), but even a celebration of just how much and how often Hollywood gets the science right.

Conversely, the vast majority of Hollywood writers, producers and directors don’t regularly come across PhD scientists in real life, and have to form impressions of doctors, scientists and engineers based on… other portrayals in entertainment. Scientists, after all, represent only 0.2 percent of the U.S. population as a whole, and less than 700,000 of all jobs belong to doctors and surgeons. And while these professions are amply represented on screen in number, that’s not necessarily been the case in accuracy. The insular self-reliance of screenwriters on their own biases has led to stereotyping and pigeonholing of scientists into a series of familiar archetypes (nerds, aloof omniscient sidekicks), as Grazier and Cass take us through a thorough, labyrinthine archive of TV and movie scientists. But as scientists have become more involved in advising productions, and have become more prominent and visible in today’s innovation-driven society, their on screen counterparts have likewise become a more accurate reflection of these demographics – mainstream hits like The Big Bang Theory, CSI (and its many procedural spinoffs), Breaking Bad and films like Gravity, The Martian, Interstellar and The Imitation Game are just a recent sampling.

If you’re going to teach a diverse group of readers about the principles of physics, astronomy, quantum mechanics and energy forms, it’s best to start with the basics. Even if you’ve never picked up a physics textbook, Hollyweird Science provides a fundamental overview of matter, mass, elements, energy, planet and star formation, time, radiation and the quantum mechanics of universe behavior. More important than what these principles are, Grazier discerns what they are not, with running examples from iconic television series, movies and sci-fi characters. What exactly is the difference between weight and mass and force, per the opening scene of the film Gravity? How are different forms of energy classified? Are the radioactive giants of Godzilla and King Kong realistic? What exactly happens when Scotty is beamed up? Buoying the analytical content are a myriad of interviews with writers and producers, expounding honestly about working with scientists, incorporating science into storytelling and where conflicts arose in the creative process.

People who want to delve into more complex science can do so through “science boxes” embedded throughout the book – sophisticated mathematical and physics analyses of entertainment staples, trivial and significant. Among my favorites: why Alice in Wonderland is a great example of allometric scaling, the thermal radiation of cinematography lighting, hypothesizing Einsteinian relativity for the Back To The Future DeLorean, and just how hot is The Human Torch in the Fantastic Four? (Pretty dang hot.)

The next time readers see an asteroid making a deep impact, characters zipping through interplanetary travel, or an evil plot to harbor a new form of destructive energy, they’ll have a scientific foundation to ask simple, but important, questions. Is this reasonable science, rooted in the principles of physics? Even if embellished for the sake of advancing a story, could it theoretically happen? And for Hollywood writers, how can science advance a plot or help a character solve their connundrum? In our podcast below, Dr. Grazier explains why physics and astronomy were such an important bedrock of the first book – and of science-based entertainment – and previews what other areas of science, technology and medicine future sequels will analyze.

In the long run, Hollyweird Science will serve as far more than just a groundbreaking book, regardless of its rather seamless nexus between fun pop culture break-down and serious scientific didactic tool. It’s a part of a conceptual bridge towards an inevitable intellecutal alignment between Hollywood, science and technology. Over the last 10-15 years, portayal of scientists and ubiquity of science content has increased exponentially on screen – so much so, that what was a fringe niche even 20 years ago is now mainstream and has powerful influence in public perception and support for science. Science and technology will proliferate in importance to society, not just in the form of personal gadgets, but as problem-solving tools for global issues like climate change, water access and advancing health quality. Moreover, at a time when Americans’ grasp of basic science is flimsy, at best, any material that can repurpose the universal love of movies and television to impart knowledge and generate excitement is significant. We are at the precipice of forging a permanent link between Hollywood, science and pop culture. The Hollyweird series is the perfect start.

In an exclusive podcast conversation with ScriptPhD.com, Dr. Grazier discussed the overarching themes and concepts that influenced both “Hollyweird Science” and his ongoing consulting in the entertainment industry. These include:

•How the current Golden Age of sci-fi arose and why there’s more science and technology content in entertainment than ever

•Why scientists and screenwriters are remarkably similar

•Why physics and astronomy are the building blocks of the majority of science fiction

•How the “Hollyweird Science” trilogy can be used as a didactic tool for scientists and entertainment figures

•His favorite moments working both in science and entertainment

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development. Follow us on Twitter and Facebook. Subscribe to our podcast on SoundCloud or iTunes.

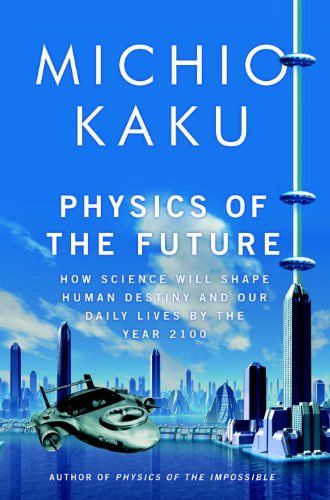

Dr. Michio Kaku recently consolidated his position as America’s most visible physicist by acting as the voice of the science community to major news outlets in the wake of Japan’s major earthquake and the recent Fukushima nuclear crisis. Dr. Kaku is one of those rare and prized few

who possesses both the hard science chops (he built an atom smasher in his garage for a high school science fair and is a co-founder of string theory) and the ability to reduce quantum physics and space time to layman’s terms. The author of Physics of the Impossible has also followed up with a new book, Physics of the Future, that aims to convey how these very principles will change the future of science and its impact in our daily modern life. (Make sure to enter our Facebook fan giveaway to win a free copy this week!) Dr. Kaku graciously sat down with ScriptPhD.com’s physics and astronomy blogger, Stephen Compson, to talk about the recent earthquake, popular science in an entertainment-driven world, and his latest book. Full interview under the “continue reading” cut.

Hang on Mom, I’m Building an Atom Smasher!

Michio Kaku’s multi-faceted success may seem to be, as Einstein said, the hallmark of true mastery over any advanced subject. But to fully appreciate the extent of Dr. Kaku’s gift for patient summary to the scientifically ignorant, ask yourself when you last saw an internationally respected physicist appear on Fox & Friends.

“It’s not that you want to be this kind of person when you’re a young kid,” the doctor tells me in the middle of his post-quake media marathon: “I’m sure that when Carl Sagan was a young astronomer, he did not say that he wanted to do this. When Carl Sagan was a kid, he read Science Fiction. He read John Carter of Mars and dreamed about going to Mars, that’s how he got his start. For me it was daydreaming about Einstein’s unified field theory. I didn’t know what the theory was, but I knew that I wanted to take a hand in trying to complete it. So you don’t really plan these things, they just sort of happen.”

Another breadwinning talent that sets him apart from high-level physics peers is that Dr. Kaku isn’t afraid to address technologies and phenomena that only exist in science fiction. His Physics of the Impossible is a scientific examination of phasers, force fields, teleportation, and time travel. One of the reasons ScriptPhD.com exists is that too many scientists will dismiss such concepts offhand, but Dr. Kaku has made a career of treating them seriously in published works, his radio broadcasts, and his TV show Sci Fi Science on the Science Channel. His latest book Physics of the Future: How Science Will Shape Human Destiny and Our Daily Lives by the Year 2100 puts forth the bold argument that technology will imbue men and women with godlike powers in less than a hundred years, with specific examinations of the current field and estimated times of arrival on things like artificial intelligence, telekinesis (through implanted brain sensors) and molecular medicine that will dramatically extend the human lifespan.

ScriptPhD: Most scientists are very cautious about making the kinds of predictions that you do in The Physics of the Future. Why do you think it’s important for scientists to address the unknown?

Michio Kaku: Because the bottom line is the taxpayer has to decide what to support with their tax money. With funds being so low, we scientists have to learn how to sing for our supper. After World War 2, we gave the military the atomic bomb. They were so impressed they just gave us anything we wanted: accelerators and atom smashers, all sorts of high-tech stuff. And then with the Cold War, the aerospace program pretty much got whatever it wanted. Now we’re back to normal: lean times where every penny is pinched, and we have to realize that unless you can interact with the taxpayer, you’re going to lose your project.

Like what happened in 1993, we lost the Supercollider. That I think was a turning point in the physics community. This eleven billion dollar machine was lost and it went to Europe in a much smaller version called the Large Hadron Collider. We failed to convince the taxpayer that the Supercollider was worthwhile, so they said, ‘We’re not going to fund you.’ That was a shock. When it comes to non-military technology, where the public definitely has a say in these matters, unless we scientists can make a convincing argument to build space telescopes and particle accelerators, the public is gonna say, ‘These are just toys. High tech toys for scientists. They have no relationship to me.’ So it’s important for very practical reasons, if only to keep our grants going, that we scientists have to learn how to address the average person. President Barack Obama has made this a national priority. He says, ‘We have to create the Sputnik moment for our young people.’ My Sputnik moment was Sputnik.

Chasing Martian Princesses

SPhD: What could be the Sputnik moment for the children of today?

MK: We have the media, which is such a waste in the sense that you can actually feel your IQ get lower as you watch TV. But there is the Discovery Channel and the Science Channel and different kinds of programming where you can use beautiful special effects to illustrate exploding stars and Mars and elementary particles. This didn’t exist when I was young. There were no Television outlets. It was just dry, dull books in the library that talked about these things. With such gorgeous special effects on cable television to explain these things, there is no excuse. These are cable outlets where we can reach the public, millions of them, with high technology.

I had two role models when I was a kid. The first was Albert Einstein. I wanted to help him complete his unfinished theory, the unified field theory. But on Saturdays I used to watch Flash Gordon on TV. I loved it! I watched every single episode. Eventually I figured out two things. First: I didn’t have blond hair and muscles. And second, I figured out it was the scientist who drove the entire series. The scientist created the city in the sky, the scientist created the invisibility shield, and the scientist created the starship.

And so I realized something very deep: that science is the engine of prosperity. All the prosperity we see around us is a byproduct of scientific inventions. And that’s not being made clear to young people. If we can’t make it clear to young people they’re not going to go into science. And science will suffer in the United States. And that is why we have to inspire young people to have that Sputnik moment.

SPhD: So you think that science fiction is a good avenue for bringing people into science and getting them excited about it?

MK: We scientists don’t like to admit this, it’s almost scandalous. But it’s true. The greatest astronomer of the twentieth century became the greatest astronomer of the twentieth century because of science fiction.

His name was Edwin Hubble. He was a small country lawyer in Missouri and he remembered the wonderment and passion he felt as a child reading Jules Verne. His father wanted him to continue in law; he was an Oxford scholar. But Hubble said no. He quit being a lawyer, went to the university of Chicago, got his PhD and went along to discover that the universe was expanding. And he did it all because as a child he read Jules Verne.

And Carl Sagan decided to become an astronomer because of Edgar Rice Burrough’s John Carter of Mars series, because he dreamed of chasing the beautiful martian princess over the sands of mars.

Here’s what I don’t like about modern science fiction. A lot of the novels are sword and sorcery. Instead of creating a society for the future, they’re going back to barbarism, they’re going back to feudalism and slavery. Once in a while, yeah, I like to read it, but I get the feeling that it’s not pushing civilization forward.

When I was a young kid , it was called hard science fiction – rocket ships, journeys to the unknown, incredible inventions like time machines and stuff like that, it was less sword and sorcery, less about having big muscles chasing beautiful women and killing your enemies, less Conan the Conquerer. Science fiction stories that talk about the future are much more uplifting for young kids and also point them in the right direction. Sword and sorcery is not a good career path for the average kid.

SPhD: On average, what do you think of the modern media’s treatment of physics?

MK: The Discovery Channel and the Science Channel are one of the few outlets where scientists can roam unimpeded by the restraints of Hollywood, which says you have to have large market share and you can’t get big concepts to people. And one person who paved the way for that was Stephen Hawking and I think that we owe him a debt in that he proved that science sells.

I remember when I wrote my first book, the publishing world said ‘Look, science does not sell. You’re going to be catering to the select few. It’s not a mass market we’re talking about.’ But there were already indications that that wasn’t true. Discover magazine, Scientific American, they both have subscriptions of about a million. And then of course when the Discovery Channel took off, that really showed that there was something that the networks did not see, and it was right in front of their face. And that was science and documentary programming.

It was always there – like Nova was a top draw for PBS – but the big networks said ‘It’s too small, it’s underneath the radar.’ So then with cable television, all the things that used to be under the radar, jumped to the forefront, Stephen Hawking outsells movie stars.

And I think that really shows something. It’s a hunger for people out there to know the answers to these cosmic questions, like what’s out there? What does it all mean? How do we fit into the larger scheme of things in the universe? There’s a real hunger for that, and of course if you watch I Love Lucy all day, you’re not gonna get the answer.

Cavemen, Picture Phones, and Horses

SPhD: On the other hand, there is a basic human instinct to resist scientific and technological change. In your book you describe this as the Caveman Principle:

“Whenever there is a conflict between modern technology and the desires of our primitive ancestors, these primitive desires win each time… Having the fresh animal in our hands was always preferable to tales of the one that got away. Similarly, we want hard copy whenever we deal with files. That’s why the paperless office never came to be… Likewise, our ancestors always liked face to face encounters….By watching people up close, we feel a common bond and can also read their subtle body language to find out what thoughts are racing through their heads…So there is a continual competition between High Tech and High Touch…we prefer to have both, but if given a choice we will choose High Touch like our caveman ancestors.”

I wondered if those weren’t generational changes that we might see come to pass in children who have grown up reading and socializing through screens.

MK: Yes slowly. There is, of course, latitude in the caveman principle. More and more people are warming up to the idea of picture phones. Picture phones first came out in the 1960’s at the World Fair, but you couldn’t touch

them with a ten foot pole. People didn’t want to have to comb their hair every time they went online. Now people are sort of getting used to it. It varies, like for instance now we have more horses than we did in 1800.

SPhD: Horses?

M: Yeah! Horses are used for recreational purposes. There are more recreational horses today than there were horses for a small American population in 1800.

Take a look at theater. Back in those days, people thought that theater would be extinguished by radio, then they thought television would replace radio, then they thought the internet would replace television, which would replace radio, movies, and live theater. The answer is we live with all of them.

We don’t necessarily go from one media or one thing to the next, making them previous and obsolete, there is a mix. You could become very rich if you know exactly what that mix is, but that’s the way it is with technology, we never really give up any old technology, we still have live theater on Broadway.

The Silicon Wasteland and Artificial Intelligence

SPhD: Regarding the creation of Artificial Intelligence in The Physics of the Future, you talk about the computer singularity and Moore’s law breaking down in about ten years—

MK: Silicon power will be exhausted for two reasons: first, transistors are going to be so tiny, they’ll generate too much heat and melt. Second, they’re gonna be so tiny they’re almost atomic in size and so the uncertainty principle comes in and you don’t know where they are, so leakage takes place.

SPhD: In the book you are very cautious in your treatment of quantum computers (Presumably the replacement when silicon breaks down) and how long it’s going to take us to develop them – what’s holding that technology back and why shouldn’t we think that they’ll replace silicon right away?

MK: Quantum computers remedy both those defaults because they compute on atoms themselves. The problem with quantum computers is impurities and decoherence. For quantum computing to work, the atoms have to vibrate in phase. But when you separate them, disturbances take place. This is called decoherence, when they vibrate out of phase. It is very easy to decohere atoms that are coherent. The slightest breath, a truck traveling by, even interference from a cosmic ray will ruin the coherence between atoms. That’s why the world record for quantum computing calculation is 3 times 5 is 15 – it sounds trivial, but go home tonight and try that on 5 atoms, take 5 atoms and try to multiply 3 times 5 is 15 – it’s not so easy.

SPhD: What is your definition of artificial intelligence?

MK: Well, that gets us into consciousness and stuff like that. My personal point of view is that consciousness is a continuum, and the same with intelligence. I would say that the smallest unit of consciousness would be the thermostat. The thermostat is aware of its environment – it adjusts itself to compensate for changes in the environment. That’s the lowest level of consciousness – beyond that would be insects, which basically go around mating and eating by instinct and don’t live very long. As you go up the evolutionary scale, you begin to realize that animals do plan a little bit, but they have no conception of tomorrow.

To the best of our knowledge, animals do not plan for tomorrow or yesterday, they live in the present. Everything is governed by instinct, so they sleep, they wake up, but they’re not aware of any continuity – they just hunt or whatever day by day. We’re a higher level of intelligence in the sense that we are aware of time, we’re aware of self, and we can plan for the future. So those are the ingredients of higher intelligence. Since animals have no conception of tomorrow to the best of our knowledge, very few animals have conception of self. For example, you get two fighting fishes and put them together, they’ll try to tear each other apart. When you put them next to a mirror, they try to attack the mirror – they have no conception of self. So we’re higher up. So artificial intelligence is the attempt to use machines to replicate humans.

SPhD: Do you think we’ll need to completely model human intelligence in order to create a satisfactory artificial one?

MK: No, but I think we made a huge mistake. Fifty years ago, everyone thought that the brain was a computer. People thought that was a no-brainer, of course the brain is a computer. Well, it’s not. A computer has a Pentium chip, it has a central processer, it has windows, programming, software, subroutines, that’s a computer. The brain has none of that. The brain is a learning machine.

Your laptop today is just as stupid as it was yesterday. The brain rewires itself after learning – that’s the difference. The architecture is different, so it’s much more difficult to reproduce human thoughts than we thought possible. I’m not saying it’s impossible, I think maybe by the end of the century we’ll have robots that are quite intelligent. Right now we’ve got robots that are about as intelligent as a cockroach. A stupid cockroach. A lobotomized, stupid cockroach. But in the future, you know, I could see them being as smart as mice. I could see that. Then beyond that, as smart as a dog or a cat. And then beyond that, as smart as a monkey. At that point we should put a chip in their brain to shut them off if they have murderous thoughts.

SPhD: The landscape for artificial intelligence seems very fragmented – the research branches in a lot of different directions. Do you think there will be some sort of unification for a grand theory of A.I.?

MK: It’ll be hard, because everyone is working on one little piece of a huge puzzle. Take a look at Watson, who defeated two Jeopardy experts – after that the media thought, ‘Uh oh the robots are coming, we’re gonna be put in zoos, and they’re gonna throw peanuts at us and make us dance behind bars.’

But then you ask a simple question. Does Watson know that it won? Can Watson talk about his victory? Is Watson aware of his victory? Is Watson aware of anything? And then you begin to realize that Watson is a one-trick pony. In science we have lots of one-trick ponies. Your hand calculator calculates about a million times faster than your brain, but you don’t have a nervous breakdown thinking about your calculator. It’s just a calculator, right? Same thing with Watson – all Watson can do is win on Jeopardy. So we have a long ways to go.

Burning Books and Teaching Principles

SPhD: You also talk about education and how the United States will be coming to the end of a brain drain on other countries because of our unmatched universities and the so-called genius visa. You claim that in order to maintain our position in the global economy, we’ll need to produce more qualified graduates from primary education. What changes you think need to be made to our education system to produce those graduates?

M: I don’t wanna insult them or anything, but education majors have the lowest scores among the different professionals on the SAT test. The brightest and most vigorous, the most competent of our graduates do not go into education.

In Japan for example, a sensei is considered very high in society. People bow before them—they give them presents and so on. In America we have the expression, ‘Those who can, do. Those who can’t, teach.’

First, we have to raise the education level of the education majors, then we have to throw away the textbooks. The textbooks are awful. My daughter took the Geology Regents exam in New York State, and I looked at the handbook – I felt like ripping it apart. Really stomping on it, burning it. It was the memorization of all the crystals, the memorization of all the minerals.

In the future you’ll have a contact lens with the internet in it – you’ll blink and you’ll see as many minerals as you want. You’ll blink and you’ll see all the crystals. Why do we have to memorize these things and force students to learn it? Then my daugher comes to me and says something that really shook me up, she comes up to me and says, ‘Daddy, why would anyone want to become a scientist?’

I really felt like ripping up that book. That book has done more to crush interest in science – that’s what science curriculum does, science curriculum is designed to crush interest in science. Science is about principles. It’s about concepts. It’s not about memorizing the parts of a flower. It helps to know some of these things, but if that’s all you do that’s not science, science is about principles and concepts. So we gotta change the textbooks.

SPhD: Given these contact lenses, or any form of uninterrupted access to the internet where we can access information like that and don’t need to memorize anything anymore, what should we be training young people to do?

MK: First they have to know the principles and the concepts, and they have to be able to think about how to apply these principles and concepts. For example, how many principles and concepts are there in geology? Here’s this big fat handbook, memorize this, memorize this, it goes on and on and on, right? But what is the driving principle behind geology?

Continental drift, the recycling of rock, that’s what they should be stressing. What’s the organizing principle of biology? It’s evolution. What’s the organizing principle of physics? Well, there’s Newtonian mechanics, but then there’s relativity and the quantum theory behind that. So we are talking about really a handful of principles, but you’d never know it taking these courses, because they’re all about memorizing stupid facts and figures.

Let me give you another example. I teach astronomy this semester at the college [Dr. Kaku is a professor of theoretical physics at the State University of New York]. Astronomy books are written by astronomers. I have nothing against astronomers, but they’re bug collectors. Every single footnote, every single itsy bitsy thing about this star, that star, this planet – you miss the big picture. So when it comes time for final examinations, I tell the students:

‘I wanna talk about principles.’ galactic evolution, that’s what I teach the kids about. I don’t teach them to memorize the moons of Jupiter. I don’t even know the moons of Jupiter, I could care less, but that’s what an astronomy test was a generation ago.

SPhD: Would you say that we need to educate humans from the top down and machines from the bottom up?

MK: I think that with machines we should go top down, bottom up, both. And maybe we’ll meet in the middle someplace. That’s how people are, think about it. When you’re very young you learn bottom up, you bump into things. But by the time you’re in school you learn top down and bottom up. Top down because a teacher stuffs knowledge into your head and bottom up cause you bump into things, you have real-life experiences. People learn both ways, but in the past, we’ve only tried to stress top down, realizing that bottom up is common sense.

Physics of the Future is a fantastic read for anyone interested in what’s in store for us over the next century (yes, this time there really will be flying cars). These aren’t Dr. Kaku’s pet predictions, but extrapolations based on the current cutting edge from the experts in every involved discipline. Readers will be shocked at how close these tantalizing technologies really are, and thrilled at the realization that most of us will live to see this amazing future.

Grateful thanks to Dr. Michio Kaku and Josh Weinberg and Joanne Schioppi at The Science Channel for facilitating this interview and our book giveaway. Catch Dr. Kaku on The Science Channel’s Sci Fi Science and read his two books, which are both available for purchase.

~*Stephen Compson*~

***********************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development.

Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

]]>

“I think we’re living through the greatest age of discovery our civilization has ever known,” declares British physics superstar Professor Brian Cox as a preamble for each episode of The Science Channel’s BBC import Wonders of the Solar System. Episode by episode, Dr. Cox deconstructs our wondrous Universe one focus at a time—the Sun, the Big Bang, life on other planets. But he does something even more important. He infuses his own obvious enthusiasm and passion for his field in each experiment and factoid. As a viewer, you can’t helped but be absorbed in the intergalactic vortex of knowledge. The timing of this mini-series and emergence of Cox’s exuberant personality could not be better. Funding for NASA missions has been cut dramatically, with an ongoing re-evaluation the role space exploration should play in the national budget and science ambition. American viewers should get used to Cox as a modern-day Carl Sagan, because his star is rising fast. ScriptPhD.com was extraordinarily fortunate to sit down with Dr. Cox in Los Angeles for a one-on-one podcast about the show, the current state of space exploration, and what is possible to achieve experimentally if we only try. My conversation with the inspirational, eloquent and brilliant Brian Cox, along with our review of Wonders of the Universe, under the “continue reading” cut.

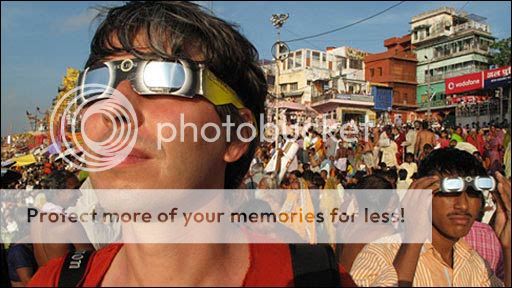

Astronomy was never my strongest suit academically. And while I’ve always had a respectful admiration for the solar system and interplanetary sciences, I was never the kind to stargaze or spend hours on the telescope on the off-chance of spotting Mars, Venus or the Saturn rings. It’s a testament, then, to the immensity, ambition and quality of The Science Channel’s latest mini-series project, Wonders of the Solar System for holding me positively captivated while screening the first two episodes. A concept as simple as a solar eclipse is the running theme for the entirety of the first episode, “Empire of the Sun.” By the time the eclipse is recorded, it is the climax to an astounding collection of facts about how rare, precious and ordered the Sun (and its position to the Earth really is). A perfect eclipse is only possible right here on planet Earth—400 times the planetary distance away from the Moon, with the Sun an exact 400 times the diameter of the Moon. No other moon in the vast expanse of the solar system has these properties. Pretty amazing stuff, right? The timing of Wonders of the Solar System could not come at a better time. With our economic and moral spirits at a nadir, it’s time to discuss the importance of space travel and exploration to our scientific, nationalistic and optimistic psyches. President Obama’s 2011 NASA budget, while providing an increase of $6 billion for technology innovation, scrapped manned space flights, including a manned mission to the Moon and any proposals of future Mars exploration. Neil Armstrong, the first man to walk on the Moon, strongly criticized the move as handicapping spaceflight and exploratory ambition. One of the things Wonders of the Universe reminds us, and that Dr. Cox reiterated in our podcast below, is that scientific discoveries come out of limitless ambition, and often from asking completely unrelated questions. Nothing is more ambitious for mankind than exploring the Universe that houses our miraculous existence. Future episodes will examine the Wonders of our atmosphere, the similarity between our planet and Mars, and most excitingly, examining the possibilities of alien life in the solar system.

Part of the appeal of Wonders is that unlike many educational platforms that talk at the viewer in order to inform, Wonders feels like an interactive, experimental experience. When Cox isn’t zipping from one far-fetched corner of the world to another (catching an aurora borealis in the Arctic Circle! a solar eclipse in India! Mars-watching in Tunisia!), he’s pointing out cool, and often eye-catching, experiments that show viewers the science and physics that makes our solar system so fantastically unique. Who would ever know that a tornado in the Midwest is actually a physics parallel to the formation of our very universe. The scientific principle at hand—conservation of angular momentum—stopped the solar system from collapsing under its own gravity during formation, allowing a stable, rotating disc of planets to form. We all know the sun is powerful, shining 1 kW of energy for meter squared of the Earth’s surface, equal to one million times the yearly power consumption of the United States in each second! But it’s a lot more fun to watch Cox show this measurement in Death Valley with a pail of water, a thermometer, and some physics. Likewise the Sun’s sunspots, a still not quite understood phenomenon that has been correlated to the Earth’s seasons and weather, which Cox illustrates with a digital camera. All of this extemporaneous experimentation is reminiscent of the best of Carl Sagan, just with a modern twist.

The Los Angeles Times, in their television review of Wonders called Brian Cox “the nerd that’s cooler than you.” Already a budding superstar in the world of particle physics (check out his TED talk on his work at CERN’s Hadron Supercollider), Cox is that perfect mix of half-scientist, half-TV star. Without him, Wonders would be a completely different endeavor. (Listen to our podcast below as an example of his charismatic eloquence.) To boot, BBC and The Science Channel spared no expenses when it came to production values. In our one on one meeting, Cox let us in on the secret that the whole of Wonders was filmed with an old-fashioned 1970s cinematic lens, lending a decidedly movie feel to the show, particularly the graphics and digital sequences. While some imagery is real, such as amazing Martian sunsets captured by the Mars rover, other digital effects (notably in the “Empire of the Sun” episode) are stunning enough to make you feel like your television is the portal window of a spacecraft in intergalactic orbit.

Wonders of the Solar System airs on The Science Channel on Thursdays at 9 PM ET.

While in Los Angeles to promote Wonders of the Solar System, Dr. Cox graciously sat down with ScriptPhD.com to discuss the show and his views on space exploration. Among our discussion topics:

•How he is still able to channel a passion for the solar system

•Why he thinks it’s critical for NASA to take risks and go to Mars

•The possibilities of life in the outer solar system and

•Why it’s a huge mistake for NASA to cut their budget for space exploration

Take a listen below:

~*ScriptPhD*~

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development.

Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

]]>

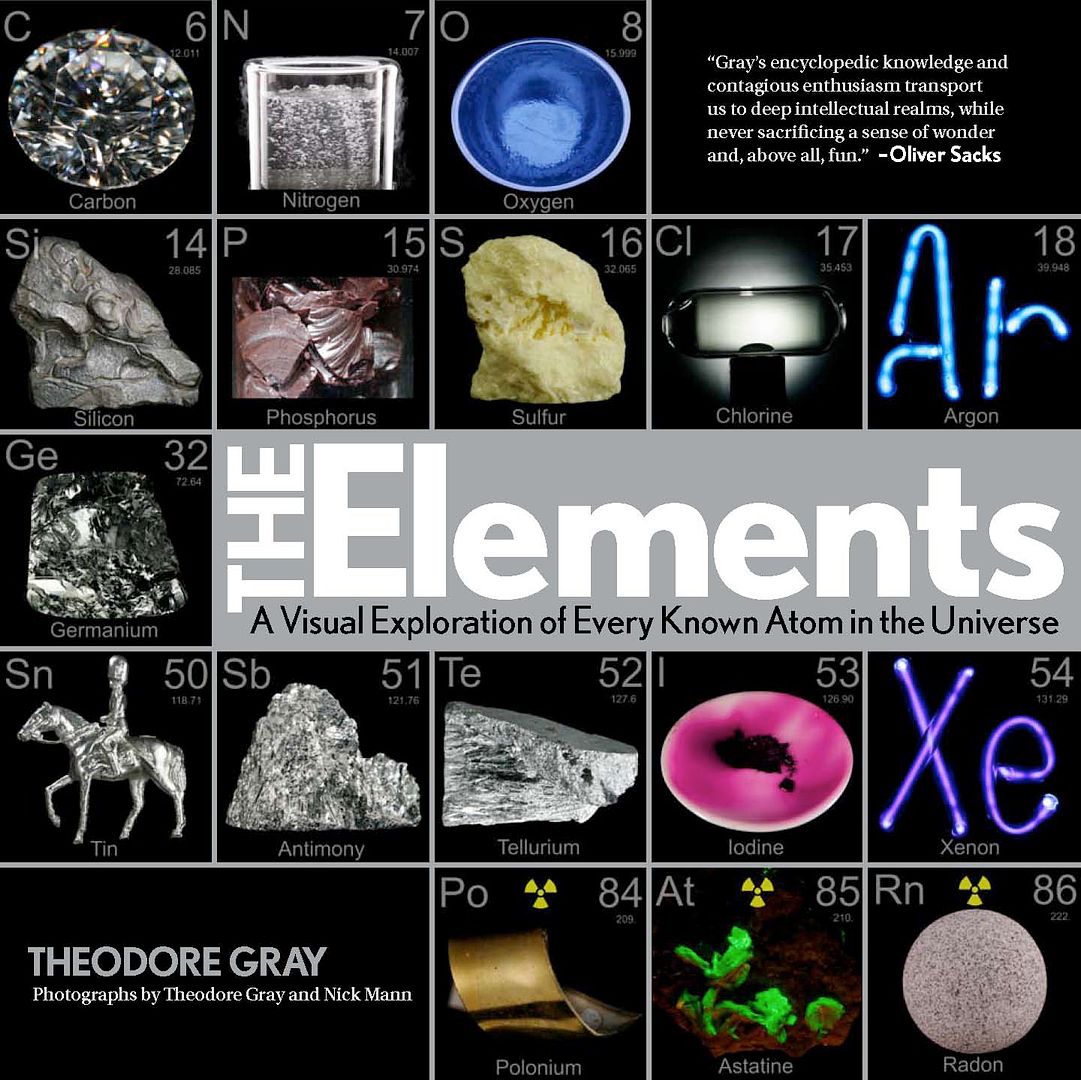

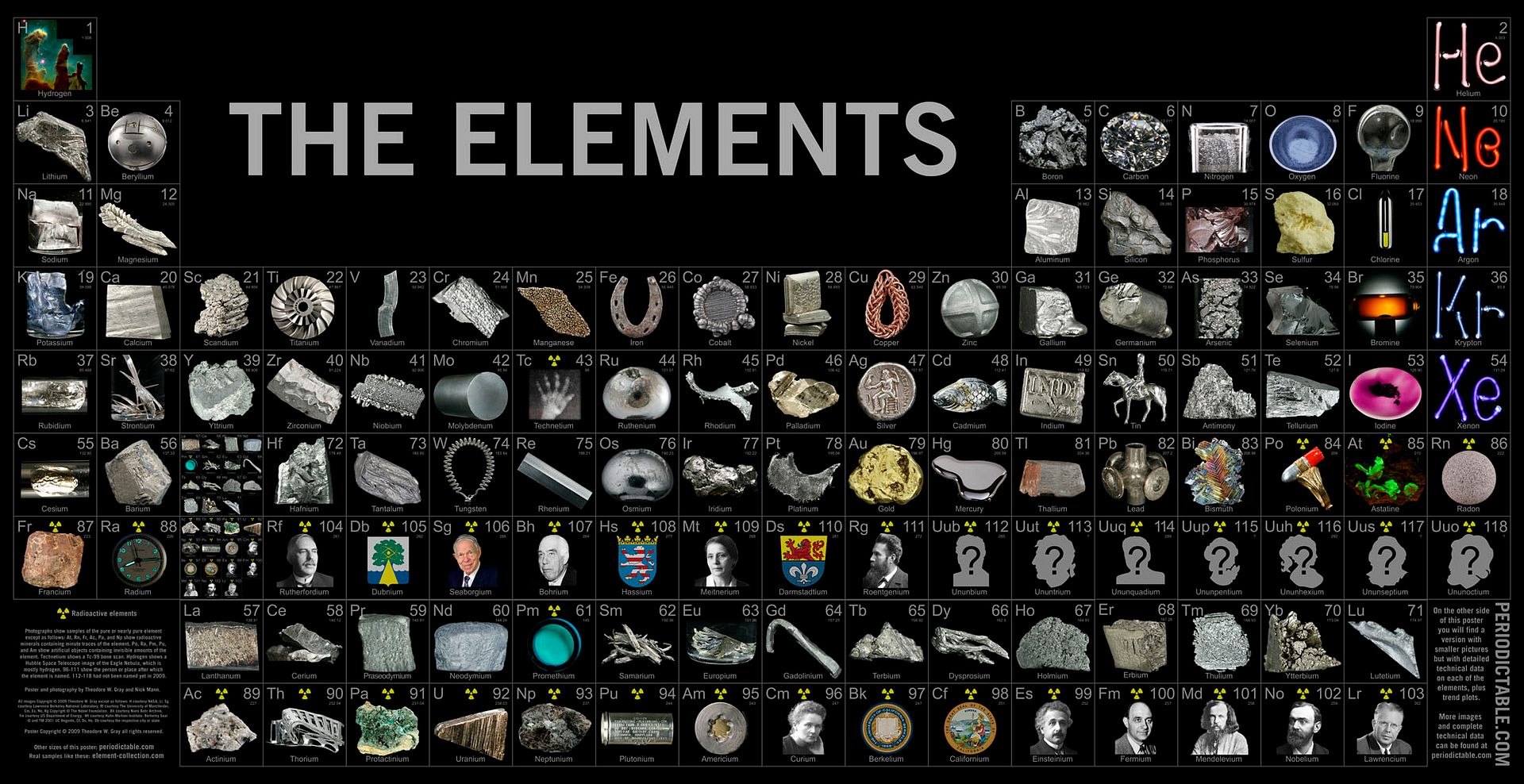

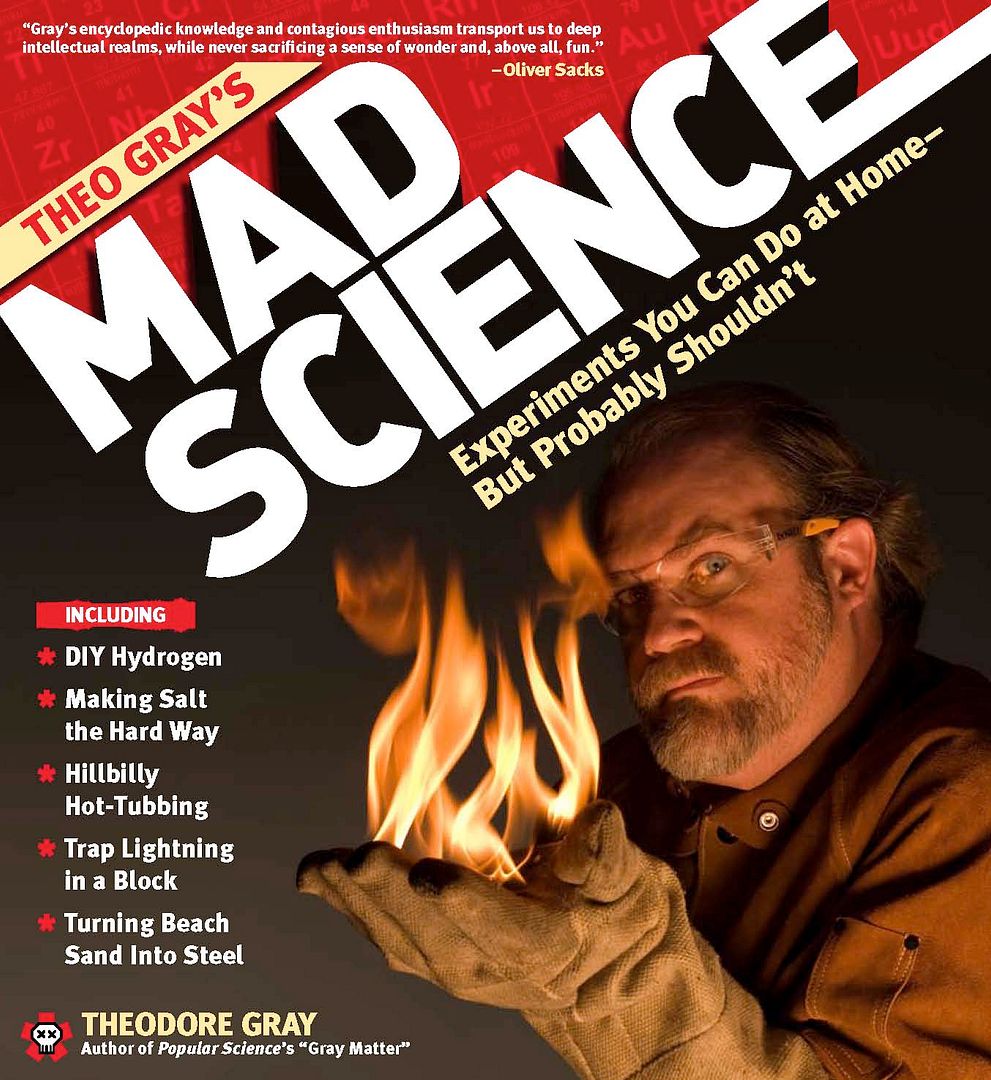

He is one of the most popular and explosive (sometimes literally!) science columnists of our day. Since 2005, he has written the Popular Science blog Gray Matter. He has been willing to try virtually any chemistry experiment known to man, all in the interest of proving a theory and educating (and entertaining) a fortunate lay audience. He has created the most widely acclaimed periodic table ever, which has been replicated into posters, an actual table, playing cards, and now, a gorgeous full-color hardcover book. Who is this mad scientist I am referring to? Why, Theodore Gray, of course! For Day 3 of Science Week, ScriptPhD.com is thrilled to review his new book The Elements, an equal parts homage to chemistry and photography. Editor Jovana Grbić sat down with Theo in a candid, in-depth interview about his books, his favorite elements, and the responsibility science writers have to informing the public. More more content, please click “continue reading.”

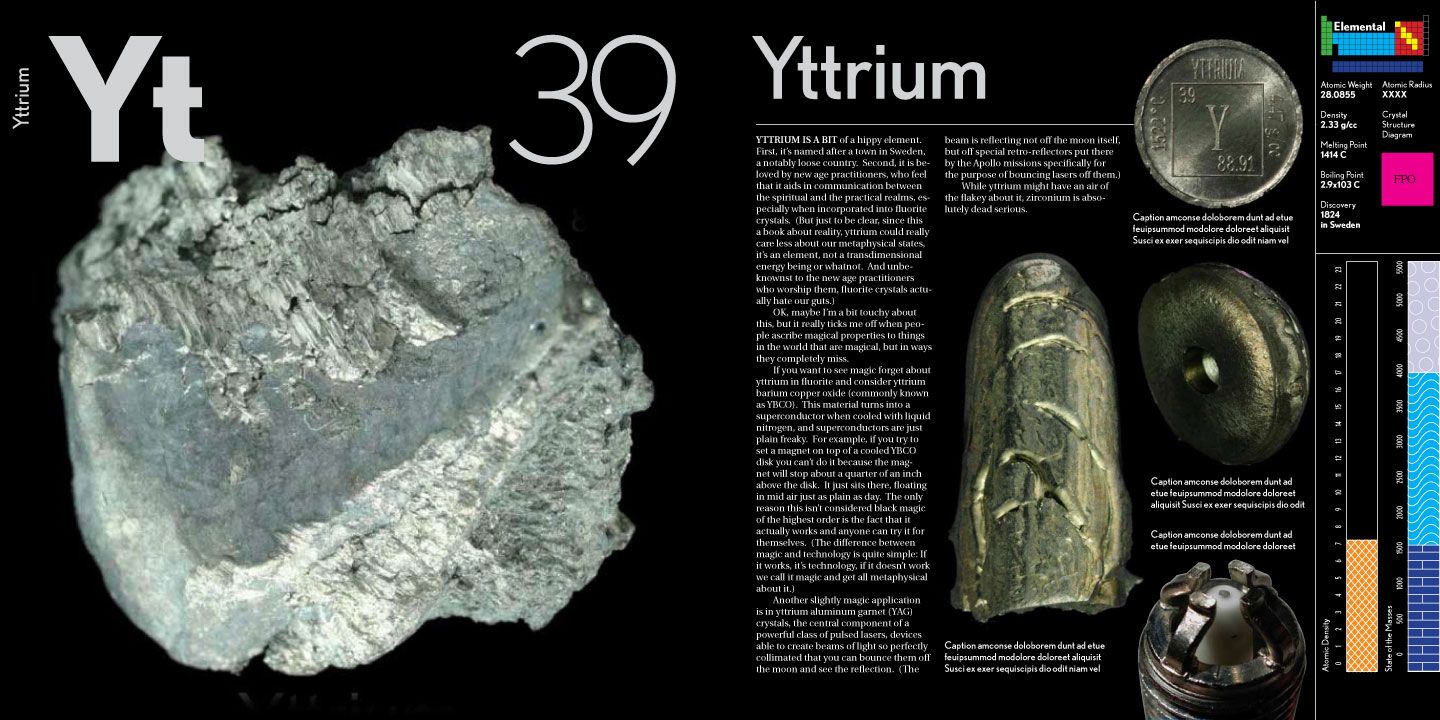

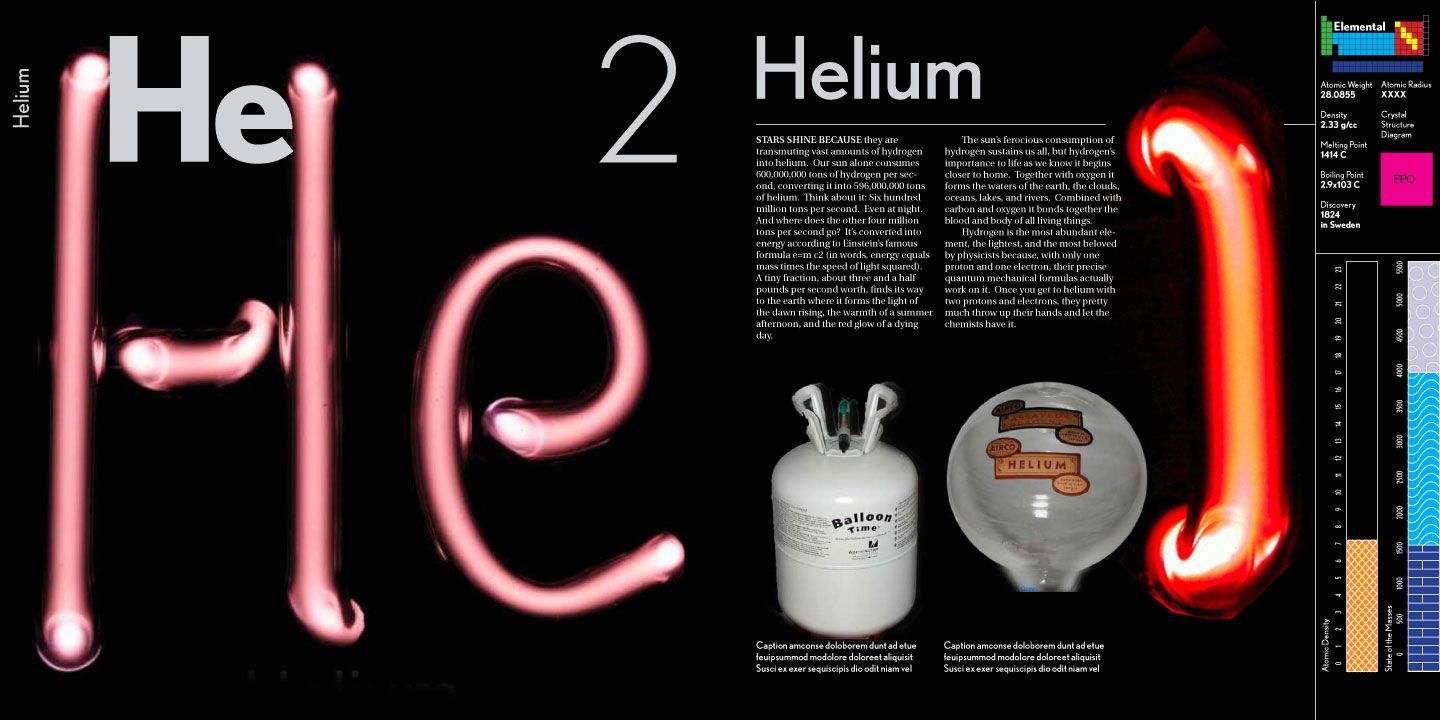

It is a staple of every high school and college science class. Its familiar shape has stayed largely the same since 1869, when Siberian chemistry professor Dmitry Ivanovich Mendeleev first grouped chemicals together according to similar properties. It is indispensable to scientists of all disciplines, and has even inspired our very own ScriptPhD.com logo! It is, of course, the periodic table of the elements. There is an immense challenge in taking such a well-known, immutable scientific entity and making people see it in a way it has never been seen before. And to do so using photography and creative writing? To the moon, Alice! Yet in Theo Gray’s gorgeous new book The Elements, this is precisely what occurs—a rebirth for ruthenium, rhodium, radium, rubidium… and the rest. Each page (as seen below) is elegantly laid out with gallery quality photography, sometimes of compounds, minerals and applications that would surprise you, and fascinating stories that turn each element into its own unique chapter in the hallowed Bible of chemical history.

Chemistry is the central science. But as you get to know the periodic table better while reading The Elements, it quickly becomes apparent that chemistry is also a science with much character. It is smelly, as is the case with sulfur. It’s sometimes a mouthful, as in the longest element name, praseodymium. It helps us control mood swings, as is the case with lithium. It helps us when we’ve overdone it at the weekend barbeque, as is the case with bismuth subsalicylate. Perhaps you know it better as Pepto-Bismol. Chemistry helps doctors and scientists to save lives. A radioactive isotope of technetium is naturally bone-seeking, and helps radiologists diagnose everything from compound fractures to cancer. Should you ever need to get an MRI, chances are you’ll have to consume a contrast dye composed of the element gadolinium. Sometimes, a fickle element both saves and takes lives. Chlorine, for example, has saved hundreds of millions of lives as an antiseptic and disinfectant in small quantities, yet is poisonous in large quantities. Likewise, selenium is an essential nutrient, but toxic in large doses. Gray also pays tribute to a sullied, marginalized element that has gotten a bad rap over the years: zirconium. If you’re considering proposing to that special someone, zirconium, like the overpriced aged carbon of which it is a replica, is near the top of the hardness scale and equally as beautiful for a fraction of the cost! On an unrelated note, thallium is one of the most effective poisons on the periodic table, owing to common symptoms that few doctors can pinpoint. For utter destruction on a wanton scale, however, one need look no further than uranium:

What is most unique and attractive about The Elements is the lengths to which it goes to envelop artists and creatives in the world of science, many of whom would be surprised how much of their craft they owe to chemistry. Iconic photographers like Ansel Adams would be nothing without magnesium, which has been widely used in camera flashes to provide light. For you font and graphic design nerds out there, one thing the typeface documentary Helvetica omitted is the magic that lies in the combination of antimony, lead and tin—it expands when solidified from a molten state. Voila! 650 years (and counting) of movable typeface. Film buffs who have enjoyed movies like Avatar (and the upcoming Hubble 3D) on IMAX would be interested to know that IMAX projectors use 15 kW short-arc Xenon projector lamps. Jimmy Hendrix, Stevie Ray Vaughan, Eric Clapton, ZZ Top, BB King, and countless other guitar legends would be silenced were it not for the obscure element samarium, which in combination with cobalt is used as a magnet for electric guitar pickups. And for all of you DJs and musical purists who agree with The ScriptPhD that no musical sound is sweeter and sharper than that of a vinyl record, did you know that phonograph needle tips are made of osmium?

Interview With Theo Gray

ScriptPhD.com Editor Jovana Grbic was fortunate to chat with Theo Gray recently, and was eager to get his perspective on the making of The Elements and Mad Science books, and some more meaty science policy issues as well.

ScriptPhD.com: Tell me a bit about the idea to put together The Elements.

Theo Gray: The book goes back quite a ways. I started collecting elements, really by accident, in 2002. We needed a table for the common area of the office I was moving into, and I didn’t want some kind of an ugly thing that you could get from an office supply catalog, so I had tables on my mind. Then, I was reading Uncle Tungsten by Oliver Sachs, and he describes a periodic table that he used to visit at the science museum. I took that literally, and thought the table literally looked like a table, and that seemed like the coolest thing—someone should make a periodic table [with slots for the elements], and at that point no one ever had! Because of the way the table was designed, it was easy to make little compartments underneath each element where you could put a sample of the element. This was right around when eBay was exploding, and it turned out you could get a great many elements there. It kind of happened by accident. One table led to another, and pretty soon, I had thousands of element [samples], pure and industrial compounds. Then I started photographing them to remember what they are. I put the cataloged list and accompanying photographs on the web, and people liked it, and the Ig Nobel Award I got in 2002 made me think that this is something other people might be interested in, too.

One thing led to another, and the cameras started getting fancier, and the photography started getting better, and pretty soon I thought I could make a poster [of the elements]. This poster is now seem on TV shows from MythBusters to Hannah Montana, which eventually led to The Elements.

SPhD: One of the things I really loved about The Elements was the humor interspersed throughout the copy. You manage to really make it fun, lively and at times hilarious. Was this writing style meant to parallel how you view science, and chemistry in particular?

TG: The other thing that I’d been doing [while compiling the book] every month, was writing a column for Popular Science Magazine, Gray matter. And it’s popular, it’s a popular magazine, as the name implies, written very much for a lay audience. So I did that every month, writing 350-450 words about a certain topic of science and working with excellent editors there to refine the language to compete with other popular publications—immediately engaging, and with some fun in it. I think it’s fair to say that over the course of the five years that I’ve been writing the column, I’d refined my ability to write consicely about a focused topic. And that’s what The Elements book is, a hundred Popular Science columns all wrapped up. In some cases, the story behind an element was so much more interesting than any practical uses we could highlight. [Editor’s note: radium is a particularly good example of this!]

SPhD: What were the biggest challenges during the making of the book and photography of the elements?

TG: In terms of the writing of the book, the rare earths, or Lanthanide series, was the toughest by far, because all of the Lanthanides are very similar [in chemical property]. In many cases, for commercial applications, they’re essentially interchangeable. If you’re making lighter flicks, it really doesn’t matter what rare earth you’re using—and they don’t even purify them, they just take them out of the ground. And many of them don’t really have any interesting applications. Although, it was interesting to discover Thulium (Tm 69), for example, which I’d gone for years thinking that no one actually cared about. But it turns out in the lighting industry they care passionately about thulium, and they couldn’t live without it [for metal halide lamps].

The challenge with the photography is that these are all essentially lumps of gray metal. 90%+ of all the elements are gray metals and shapeless. One of the few other photo periodic tables out there was published in the 1960s by Time-LIFE, and they all look the same—not very interesting! Our job was exactly like the job of a commercial photographer, an advertising photographer. They’re given a product that might be the most boring thing you ever saw, and they have to bring out its inner beauty by way of lighting and arrangement. We tried to think of the most exciting examples of each metal. We also did cheat a bit, with some of the beautiful, colorful crystals, which are not pure elements but rather compounds. But it is an excuse to put a splash of color on every page!

SPhD: You know I’m going to ask… you’re the Element King… What’s your favorite element and why?

TG: Ahh, the favorite element question! My first answer is that I don’t have a favorite child, either. But there’s different elements that I like for different reasons. Sodium, for example, if you have a lake near-by, is the element you want to have. [Editor’s note: BE CAREFUL! HIGHLY EXPLOSIVE!] On the other hand, something like titanium is a wonderful metal in every way—it doesn’t rust, it’s malleable, highly useful, strong, and many of its applications are interesting and exotic. Copper is so great as well, because it’s the only colored metal that is reasonably priced and not explosive. Cesium explodes, and gold is very expensive. That leaves copper, but people don’t tend to make sophisticated shapes out of it other than jewelry. But if I had to name two, it would be sodium and titanium.

SPhD: Let’s talk about your other book for a moment, Mad Science. Some of my favorite experiments that I want to replicate are the lightbulb, homemade pencils, 1-volt liquid battery (which I’ll use to charge up my iPod), plating the iPod, and my personal favorite, preserving a snowflake. Was there an experiment in this book that made it in or didn’t where you either felt like your life was in danger or you were like, “OK, change of plans, we’re not doing this.”?

TG: I have a policy of not doing anything dangerous. These experiments [from the book] are only dangerous if you don’t do them right, which I explain fairly well in the safety section. Because basically, I’m a complete ninny. I’m terrified of that stuff, which is the way that you ought to be. There is a good bit of thought that went into the worst case scenario, and if there was a shred of doubt, we rethought the experiment—smaller scale, or do it differently. One of the advantages of doing it for photography as opposed to in person is that we were able to get away with extremely small quantities. We also hired specialists where applicable, such as an electrical engineer for shrinking coin trick, or an industrial chemist for the chlorine experiment.

The one experiment that I suggest your readers do is the snowflake one, which is just so nice, and only took me three or four tries. The key is to keep your slide really cold and pre-cooled, and to handle them with your hands the least amount possible.

SPhD: You are, of course, most well known for your Popular Science column Gray Matter. How has writing Gray Matter, particularly focused for a lay audience, changed your role in science?

TG: It’s interesting to be faced with the challenge of trying to explain something that is actually quite complicated and deep in a format where you only have a few hundred words and you can’t assume that your audience has four semesters of college chemistry. If I were writing for Scientific American, it would be quite different and you could use a certain shorthand quite freely. Here, I have not not only explain everything, but also make it fun and entertaining. The most important thing is that I have an opportunity to speak to people, particularly young people, who probably aren’t getting any actual science anywhere else. Rather than preaching to the choir about the value and interestingness of science, I can reach out to a new audience. Often in lay magazines, it’s frustrating to read so much pseudo-science because the people doing it don’t actually know what they’re talking about. The other thing I like to do is scatter some breadcrumbs throughout my writing to leave hints or terms that can’t really be explained to encourage people to look things up on their own.

SPhD: So much of our modern culture is influenced by the growth of technology and science, which play a huge role in our lives and economy than ever before. And yet, as a whole, mainstream public knowledge of basic science can be shockingly absent or misinformed. What is the single most important thing people like you, myself and others in the science community can do to mitigate this?

TG: There’s a couple of things. One is, and I’ve written a couple of blog posts about this for Powell’s Books, that you need to be relatively fearless in getting out there and telling the truth without worrying about repercussions or consequences. I’m talking about things like creationism or homeopathy, which are two basically stupid ideas which are very widely believed. People like me have a responsibility not to beat around the bush [as to their accuracy or lack thereof]. One needs to have strong attitudes because that’s what gets people riled up. At the same time, one needs to communicate that science is something that is worth putting effort into and learning about, because it’s very powerful. If you understand it, and your competitor doesn’t, you win, in many, many situations. We see this both in technology and at the societal level, one that we’re frankly losing to China. While we’re arguing about evolution and homeopathy, they’re gathering all the natural resources they can to become the dominant global economy next Century.

SPhD: You are one of the few scientists that have crossed the barrier to entertainment and wider popular appeal. Why do you think more academics have not? Is it a problem of the public welcoming these figures, hesitation in the academic community of going mainstream, or something in the middle?

TG: It depends. There’s different motivations. I, for example, grew up in an entirely academic household; both of my parents were math professors. I completely understand that world and that mindset. The kind of articles that I write for Popular Science would be considered more than a little bit embarrassing if I were an academic and had to worry about tenure committees and citations of academic papers. It’s not a very respectable profession, from an academic point of view, and I think that keeps a lot of people out who could write for a broader popular audience. It’s also a quite different skill, one that’s taken me decades, to develop the writing style that works for a lay audience—and it’s not easy to do.

And then on the other side, there’s a resistance among the publishers and media types to take science seriously because they assume it’s going to be boring. It irritates me greatly when TV shows about science end up being frantically edited, with lots of flashy graphics going up. And you can just tell that what happened was that none of the people involved knew anything about science (or possibly cared). But if you look at a show like MythBusters, for example, it’s a fantastic science show.

SPhD: Yes! We love MythBusters!

TG: They are one of the most successful of all cable shows, and they are 95% a science show wrapped up around the theme of a “myth” that they have to “bust.” Fundamentally, what they do is pose a question and then hypothesize and answer it using the scientific method. I don’t know if people appreciate how revolutionary it is for them to do that consistently.

SPhD: This is why ScriptPhD.com loves The Discovery Channel and MythBusters so much. We are in contact with them, we’re big supporters, and we wish them, and you, a lot of luck with shepherding the next generation of curious young scientists!

TG: Delightful to talk to you as well. Thanks!

~*ScriptPhD*~

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development.

Follow us on Twitter and our Facebook fan page. Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.

]]>

poster ©2010 Home Box Office, all rights reserved