Space exploration is enjoying its greatest popularity revival since the Cold War, both in entertainment and the realm of human imagination. Thanks in large part to blockbusters like Gravity, The Martian and Interstellar, not to mention privatized innovation from companies like SpaceX, and fascination with inter-galactic colonization has never been more trenchant. Despite the brimming enthusiasm, there hasn’t been a film or TV series that has tackled the subject matter in a nuanced way. Until now. The Expanse, ambitiously and faithfully adapted by SyFy Channel from the best-selling sci-fi book series, is the best space epic series since Battlestar Galactica. It embraces similar complex, grandiose and ethically woven storylines of human survival and morality amidst inevitable technological advancement. Below, a full ScriptPhD review and in-depth podcast with The Expanse showrunner Naren Shankar.

200 years in future, humans have successfully colonized space, but not without discord. The Earth, overpopulated and severely crunched for resources, has expanded to the asteroid belt and a powerful, wealthy and now-autonomous Mars. Though the colonies of the asteroid belt are controlled by Earth (largely to pillage materials and water), its denizens are second-class citizens, exploited by wealthy corporations for deadly labor. Inter-colony friction, class warfare, resource allocation and uprising frame the backdrop for a political standoff between Mars and Earth that could destroy humanity.

Deeper questions of righteous terrorism, political conspiracy and human rights are embodied in a triumvirate of smart, interweaving plots that will eventually coalesce to unravel the fundamental mystery. Josephus Miller (Thomas Jane) is a great detective, but a lowly belter and miserable alcoholic, mostly paid to settle minor Belt security and corporate matters. But when he’s hired to botch an investigation into the disappearance of a wealthy Earth magnate’s family, Miller starts to uncover dangerous connections between political unrest and the missing heiress. Jim Holden (Steven Strait) is a reluctant hero – a “Belter” ship captain thrown into a tragic quest for justice – who unwittingly leads his mates directly into the conflict between Mars and Earth and, as he delves deeper, unravels a potentially calamitous galactic threat. Finely balancing this tightwire is Chrisjen Avasarala (Shohreh Aghdashloo), the Deputy Undersecretary of the United Nations, who must balance the moral quandaries of peacekeeping with a steely determination to avoid war at all costs.

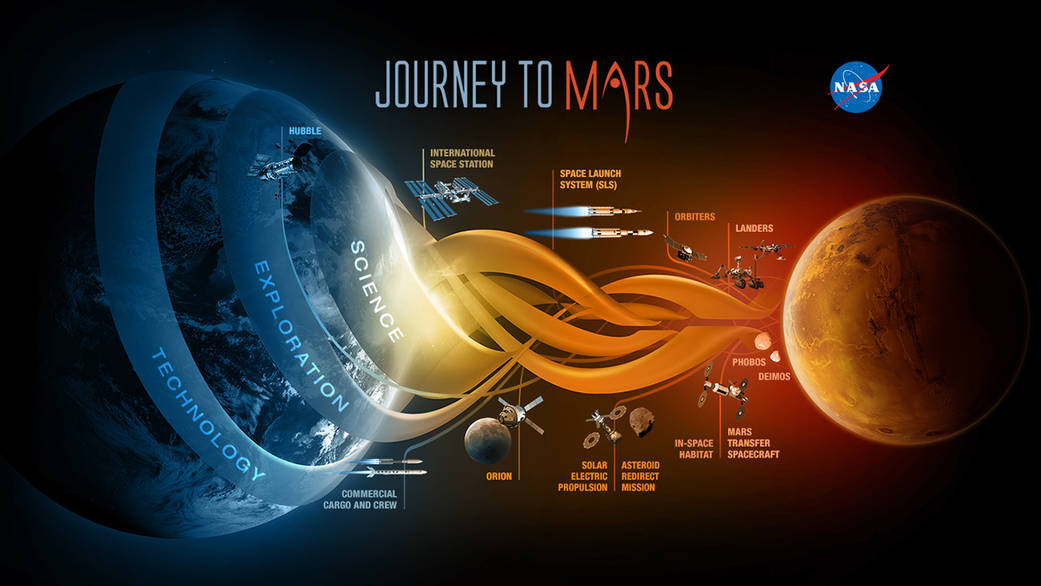

Colonization is a very trendy topic right now in space and astrophysics circles, particularly on Mars, having discovered liquid water, which fosters favorable conditions for the evolution and sustainability of life. Could it ever actually happen? There would certainly be considerable engineering and habitability obstacles.

For now, modest manned exploration of Mars and Europa by human astronauts is a tentative first step for NASA.

The Expanse assumes all these challenges and explorations have ben overcome, and picks up at a time when humans biggest problem isn’t conquering space – it’s conquering each other. The show is sleek and very technologically adept, in direct visual contrast to the more dilapidated environment of Battlestar Galactica. Fans of geek chic technology can ogle at complex docking stations as ships move around the belt to and from Earth and Mars, see through tablets, pills that induce omniscience during interrogations and ubiquitous voice-controlled artificial intelligence. However, though a new way of life has been established, remnants of our current quotidian existence and human essence are still instantly recognizable. This isn’t the techno-invasive dystopia of Blade Runner or Minority Report.

Like, Battlestar Galactica, (a show The Expanse will invariably be compared to) there is a crisp, smart overarching commentary on human existentialism under tense circumstances. Survival and life in space. Adapting to the changing gravitational forces and physical conditions of travel between planets and the asteroid belt colonies. Most importantly, navigating the incendiary dynamics of a species on the brink of all-out galactic warfare. As show runner Naren Shankar mentions in our podcast below, all great sci-fi is historically rooted in allegory – the exploration of disruptive technological innovation (and the fear thereof) as a symbol of combating inequality and/or political injustice. At a time of great social upheaval in our world, a fight for dwindling global resources and against proliferating environmental devastation, many of the themes explored in The Expanse books and series are eerily salient. Perhaps they also act as a reminder that even if a technological revolution facilitates an eventual expansion into outer space, our tapestry of inclinations (good and bad) is sure to follow.

Naren Shankar, the executive producer and show runner of The Expanse, helped develop the adaptation of the sci-fi series buoyed by decades of merging the creative compasses of science and entertainment. A PhD-educated physicist and engineer, Shankar was a writer/producer on Star Trek: The Next Generation, Almost Human and Grimm, as well as a co-showrunner of the groundbreaking forensics procedural CSI. Dr. Shankar exclusively joined the ScriptPhD.com podcast to discuss his transition from PhD scientist to working Hollywood writer, the lasting iconic impact of Star Trek and CSI and how The Expanse evokes the best allegory and elements of the sci-fi genre to tell an existential narrative. Listen below:

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development. Follow us on Twitter and Facebook. Subscribe to our podcast on SoundCloud or iTunes.

Dr. Kevin Grazier has made a career of studying intergalactic planetary formation, and, over the last few years, helping Hollywood writers integrate physics smartly into storylines for popular TV shows like Battlestar Galactica, Eureka, Defiance and the blockbuster film Gravity. His latest book, Hollyweird Science: From Quantum Quirks to the Multiverse traverses delightfully through the science-entertainment duality as it first breaks down the portrayal of science in movies and television, grounding the audience in screenplay lexicon, then elucidates a panoply of physics and astronomy principles through the lens of storylines, superpowers and sci-fi magic. With the help of notable science journalist Stephen Cass, Hollyweird Science is accessible to the layperson sci-fi fan wishing to learn more about science, a professional scientist wanting to apply their knowledge to higher-order examples from TV and film or Hollywood writers and producers of future science-based materials. From case studies, to in-depth interviews to breaking down the Universe and its phenomena one superhero and far-away galaxy at a time, this first volume of an eventual trilogy is the essential foundation towards understanding how science is integrated into a story and ensuring that future TV shows and movies do so more accurately than ever before. Full ScriptPhD review and podcast with author and science advisor Dr. Grazier below.

Most people who watch movies and TV shows never went to film school. They are not familiar with the intricacies of three-act structure, tropes, conceits and MacGuffins that are the skeletal framework of a standard storytelling toolkit. Yet no genre is more rooted in and dependent on setup and buying into a payoff than sci-fi and films conceptualized in scientific logic. Many, if not most, critiques of science in entertainment don’t fully acknowledge that integrating abstruse science/technology with the complex constraints of time, length, character development and screenplay format is incredibly demanding. Hollyweird Science does point out some egregious examples of “information pollution” and the “Hollywood Curriculum Cycle” – the perpetuation bad, if not fictitious, science. But after grounding the reader in a primer of the fundamental building blocks of movie-making and TV structure, not only is there a more positive, forgiving tone in breaking down the history of the sci-fi canon (some of which predicted many of the technological gadgets we enjoy today), but even a celebration of just how much and how often Hollywood gets the science right.

Conversely, the vast majority of Hollywood writers, producers and directors don’t regularly come across PhD scientists in real life, and have to form impressions of doctors, scientists and engineers based on… other portrayals in entertainment. Scientists, after all, represent only 0.2 percent of the U.S. population as a whole, and less than 700,000 of all jobs belong to doctors and surgeons. And while these professions are amply represented on screen in number, that’s not necessarily been the case in accuracy. The insular self-reliance of screenwriters on their own biases has led to stereotyping and pigeonholing of scientists into a series of familiar archetypes (nerds, aloof omniscient sidekicks), as Grazier and Cass take us through a thorough, labyrinthine archive of TV and movie scientists. But as scientists have become more involved in advising productions, and have become more prominent and visible in today’s innovation-driven society, their on screen counterparts have likewise become a more accurate reflection of these demographics – mainstream hits like The Big Bang Theory, CSI (and its many procedural spinoffs), Breaking Bad and films like Gravity, The Martian, Interstellar and The Imitation Game are just a recent sampling.

If you’re going to teach a diverse group of readers about the principles of physics, astronomy, quantum mechanics and energy forms, it’s best to start with the basics. Even if you’ve never picked up a physics textbook, Hollyweird Science provides a fundamental overview of matter, mass, elements, energy, planet and star formation, time, radiation and the quantum mechanics of universe behavior. More important than what these principles are, Grazier discerns what they are not, with running examples from iconic television series, movies and sci-fi characters. What exactly is the difference between weight and mass and force, per the opening scene of the film Gravity? How are different forms of energy classified? Are the radioactive giants of Godzilla and King Kong realistic? What exactly happens when Scotty is beamed up? Buoying the analytical content are a myriad of interviews with writers and producers, expounding honestly about working with scientists, incorporating science into storytelling and where conflicts arose in the creative process.

People who want to delve into more complex science can do so through “science boxes” embedded throughout the book – sophisticated mathematical and physics analyses of entertainment staples, trivial and significant. Among my favorites: why Alice in Wonderland is a great example of allometric scaling, the thermal radiation of cinematography lighting, hypothesizing Einsteinian relativity for the Back To The Future DeLorean, and just how hot is The Human Torch in the Fantastic Four? (Pretty dang hot.)

The next time readers see an asteroid making a deep impact, characters zipping through interplanetary travel, or an evil plot to harbor a new form of destructive energy, they’ll have a scientific foundation to ask simple, but important, questions. Is this reasonable science, rooted in the principles of physics? Even if embellished for the sake of advancing a story, could it theoretically happen? And for Hollywood writers, how can science advance a plot or help a character solve their connundrum? In our podcast below, Dr. Grazier explains why physics and astronomy were such an important bedrock of the first book – and of science-based entertainment – and previews what other areas of science, technology and medicine future sequels will analyze.

In the long run, Hollyweird Science will serve as far more than just a groundbreaking book, regardless of its rather seamless nexus between fun pop culture break-down and serious scientific didactic tool. It’s a part of a conceptual bridge towards an inevitable intellecutal alignment between Hollywood, science and technology. Over the last 10-15 years, portayal of scientists and ubiquity of science content has increased exponentially on screen – so much so, that what was a fringe niche even 20 years ago is now mainstream and has powerful influence in public perception and support for science. Science and technology will proliferate in importance to society, not just in the form of personal gadgets, but as problem-solving tools for global issues like climate change, water access and advancing health quality. Moreover, at a time when Americans’ grasp of basic science is flimsy, at best, any material that can repurpose the universal love of movies and television to impart knowledge and generate excitement is significant. We are at the precipice of forging a permanent link between Hollywood, science and pop culture. The Hollyweird series is the perfect start.

In an exclusive podcast conversation with ScriptPhD.com, Dr. Grazier discussed the overarching themes and concepts that influenced both “Hollyweird Science” and his ongoing consulting in the entertainment industry. These include:

•How the current Golden Age of sci-fi arose and why there’s more science and technology content in entertainment than ever

•Why scientists and screenwriters are remarkably similar

•Why physics and astronomy are the building blocks of the majority of science fiction

•How the “Hollyweird Science” trilogy can be used as a didactic tool for scientists and entertainment figures

•His favorite moments working both in science and entertainment

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development. Follow us on Twitter and Facebook. Subscribe to our podcast on SoundCloud or iTunes.

The Martian, is a film adaptation of the inventive, groundbreaking hard sci-fi adventure tale. Like Robinson Crusoe on Mars, it’s a triumph of engineering and basic science, a love letter to innovation and the greatest feats humans are capable of through collaboration. Directed by sci-fi legend Ridley Scott, and following in the footsteps of space epics Gravity and Interstellar, The Martian offers a stunning virtual imagination of Mars, glimpses of NASA’s new frontier – astronauts on Mars – and the stakes of a mission that will soon become a reality. Below, ScriptPhD.com reviews The Martian (an Editor’s Selection) and, with the help of a planetary researcher at The California Science Center, we break down some basics about Mars missions and the planetary science depicted in the film (interactive video).

That the film version of The Martian even exists is a testament to the unlikely success story of Andy Weir’s novel. A self-described science geek and gainfully employed computer programmer, he started writing a novel on the side, self-publishing chapter by chapter on an independent website. Word spread naturally, readers flocked, eventually, a completed book found a publisher and inevitably Hollywood came calling. Sounds about as realistic as… an astronaut being abandoned on a planet and having to make his own way back to Earth. But this is the exact fast-paced, thrilling plot behind one of the biggest hard sci-fi adventures of all time. Amidst an unexpected Martian sand storm, the crew of Ares 3 (the third fictionalized manned mission to Mars) becomes separated and erroneously thinks one of their members, Mark Watney, has died. They scramble to evacuate the red planet, leaving him very much alive with minimal food, water and tools to fend for himself and no communication to speak of.

With chemistry, botany, physics, engineering, home garage junk science and some self-deprecating humor, Watney must protect himself in the harsh Martian setting, figure out a way to let NASA know he’s alive, craft an escape plan, all while managing to overcome one after another devastating setback. At its heart, The Martian is a pure self-reliant survival tale, a staple of popular fiction. Despite its space setting and unapologetically elaborate scientific plot, it’s a story about a really smart guy who is – in the words of one of the many 70s disco songs throughout – stayin’ alive.

The movie adaptation remains mostly faithful to the central plot, necessarily trimming a few of Mark Watney’s perilous side adventures and unnecessarily supplanting Weir’s sardonic dialogue and one liners. The film sometimes lacks the ubiquitous sense of immediate urgency and desperation present throughout the book, but it makes up for it with more polished transitions and the ability to “think big” that is unique to cinema and critical to a science fiction. Most importantly, Matt Damon (as Watney) ably juggles vulnerability, scientific confidence and geek-chic sarcasm of an iconic sci-fi character.

One of the strengths of Weir’s book is the reader’s ability to visualize every detail of the Mars landscape and its phenomena through intricate first-person storytelling. The most important transition from such a detailed book to film is translating that visual realm, from the rolling red Martian plains and hills to the contrast of the confined space shuttle his crew is in to the chaotic flurry of NASA and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. The vastness of the Martian terrain, incurring both abject loneliness and giddy awe in Watney (with whom we spend the majority of the film) is brilliantly rendered by Scott’s wide angles and grand, sweeping shots. It renders more power to a scene in which the astronaut, unsure if he’ll make it out alive, asks that his parents be told how happy he still is as a scientist, despite everything. “Tell them I love what I do. It’s important. It’s bigger than me.” In that moment, we truly believe him.

For a narrative in which the main character is forced to “science the s—t” out of his predicament, not knowing that back on Earth NASA is doing the very same, one would expect an endless supply of science and technology magic. In that regard, neither the book nor the movie disappoints. But what is truly surprising is the degree of plausibility and accuracy woven throughout the space survival tale. While all recent space films, including Gravity and Interstellar, have been meticulously well researched and inventive, The Martian compounds imagination with incredible scientific reality. For one thing, much of the technology already used by NASA is incorporated into the story. For another, author Andy Weir and director Ridley Scott reaffirmed how hard they worked to get the science right. “Originally The Martian was a serial that I had posted on my website chapter-by-chapter,” said author Weir. “If there were errors in the physics or chemistry problems or whatever, [my readers] would email me. It was great. I got sort of crowd-sourced fact checking. And while some of the science is still not quite air-tight, not only does The Martian take its science very seriously, it managed to thoroughly impress the toughest customer of all – NASA itself!

(For a full Mars primer and breakdown of the planetary science seen in the film, see ScriptPhD.com’s excusive video below.)

With all of the people furiously working to keep Watney alive – the NASA ground crew, Jet Propulsion Laboratory engineers, the Ares 3 crew, and even Watney himself – the real hero and main star of The Martian is science itself. Science facilitates Watney’s survival of the initial Martian storm, allows him to generate food and water to stay alive, traverse the unforgiving landscape and engineer a series of clever technological adaptations to establish communication and series of hopeful escape plans. Most importantly, it allows for an unlikely international alliance to save Watney. “It just goes to show,” [NASA Director] Teddy [Sander] said. “Love of science is universal across all cultures.” This important line from the book is reiterated in the film.

NASA has stated that it aspires to execute a manned mission to Mars by about 2030, a project no doubt buoyed by the exciting revelation that the Curiosity rover has found evidence of flowing water nearby. Expensive, dangerous missions, however, rely on public support for momentum – particularly because NASA research is publicly funded. And movies are often an important cultural gateway to engender and grow such support. NASA advisors of sci-fi film The Europa Report hoped it would inspire a real mission someday. One of ScriptPhD’s favorites from the last few years, Moon, and ambitious sci-fi hit Interstellar have the potential to re-ignite a new space race.

In an exclusive podcast with ScriptPhD.com a few years ago, noted astronomer and science communicator Brian Cox fervently advocated that NASA embrace its greatest challenge to date – manned exploration of Mars: because it’s hard, because we are meant to push the boundaries of the far edges of our galactic frontiers, because space exploration is the greatest universal manifestation of our ability to innovate and engineer. To the extent that The Martian manages to inspire and ignite this idea wih the mainstream public, it will stake claim as more than just a sci-fi benchmark. It will be seen as a catalyst for exploration history. After all, NASA did just announce plans to finally explore life on Jupiter’s moon Europa as depicted in Stanley Kubrik’s classic 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Interested in learning more about all the planetary science that goes into executing a Mars mission? The likelihood of Watney’s survival and some of the technical and scientific feats he pulls off on the red planet? I was privileged to head out to the California Science Center, location of the first ever Viking Mars rover prototype, to break down the science of Mars missions with Devin Waller, a planetary scientist and former Mars researcher.

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development. Follow us on Twitter and Facebook. Subscribe to our podcast on SoundCloud or iTunes.

From a sci-fi and entertainment perspective, 2015 may undoubtedly be nicknamed “The Year of The Robot.” Several cinematic releases have already explored various angles of futuristic artificial intelligence (from the forgettable Chappie to the mainstream blockbuster Marvel’s Avengers: Age of Ultron to the intelligent sleeper indie hit Ex Machina), with several more on the way later this year. Two television series premiering this summer, limited series Humans on AMC and Mr. Robot on USA add thoughtful, layered (and very entertaining) discussions on the ethics and socio-economic impact of the technology affecting the age we live in. While Humans revolves around hyper-evolved robot companions, and Mr. Robot a singular shadowy eponymous cyberhacking organization, both represent enthusiastic Editor’s Selection recommendations from ScriptPhD. Reviews and an exclusive interview with Humans creators/writers Jonathan Brackley and Sam Vincent below.

Never in human history has technology and its potential reached a greater permeation of and importance in our daily lives than at the current moment. Indeed, it might even be changing the way our brains function! With entertainment often acting as a reflection of socially pertinent issues and zeitgeist motifs, it’s only natural to examine the depths to which robots (or any artificial technology) might subsume human life. Will they take over our jobs? Become smarter than us? Nefariously affect human society? These fears about the emotional lines between humans and their technology are at the heart of AMC’s new limited series Humans. It is set in the not-too-distant future, where the must have tech accessory is a ‘synth,’ a highly malleable, impeccably programmed robotic servant capable of providing any services – at the individual, family or macro-corporate level. It’s an idyllic ambition, fully realized. Busy, dysfunctional parents Joe and Laura obtain family android Anita to take care of basic housework and child rearing to free up time. Beat cop Pete’s rehabilitation android is indispensable to his paralyzed wife. And even though he doesn’t want a new synth, scientist George Millikan is thrust with a ‘care unit’ Vera by the Health Service to monitor his recovery from a stroke. They can pick fruit, clean up trash, work mindlessly in factories and sweat shops make meals, even provide service in brothels – an endless range of servile labor that we are uncomfortable or unwilling to do ourselves.

Humans brilliantly weaves the problems of this artificial intelligence narrative into multiple interweaving story lines. Anita may be the perfect house servant to Joe, but her omniscience and omnipresence borders on creepiness to wife Laura (and by proxy, the audience). Is Dr. Millikan (who helped craft the original synth technology) right that you can’t recycle them the way you would an old iPhone model? Or is he naive for loving his synth Odi like a son? And even if you create a Special Technologies Task Force to handle synth-related incidents, guaranteeing no harm to humans and minimal, if any, malfunctions, how can there be no nefarious downside to a piece of technology? They could, in theory, be obtained illegally and reprogrammed for subversive activity. If the original creator of the synths wanted to create a semblance of human life – “They were meant to feel,” he maintains – then are we culpable for their enslaved state? Should we feel relieved to see a synth break out of the brothel she’s forced to work in, or another mysterious group of synths that have somehow become sentient unite clandestinely to dream of a dimension where they’re free?

In reality, we already are in the midst of an age of artificial intelligence – computers. Powerful, fast, already capable of taking over our workforce and reshaping our society, they are the amorphous technological preamble to more specifically tailored robots, incurring all of the same trepidation and uncertainty. Mr. Robot, one of the smartest TV pilots in recent memory, is a cautionary tale about cyberhacking, socioeconomic vulnerability and the sheer reliance our society unknowingly places in computers. Its central themes are physically embodied in the central character of Elliot, a brilliant cybersecurity engineer by day/vigilante cyberhacker by night, battling schizophrenia and extreme social anxiety. To Elliott, the ubiquitous nature of computer power is simultaneously appealing and repulsive. Everything is electronic today – money, corporate transactions, even the way we communicate socially. As a hacker, he manipulates these elements with ease to get close to people and to solve injustice (carrying a Dexter-style digital cemetery of his conquests). But as someone who craves human contact he loathes the way technology has deteriorated human interaction and encouraged nameless, faceless corporate greed.

Elliot works for Allstate Security, whose biggest client is an emblem of corporate evil and economic diffidence. When they are hacked, Elliot discovers that it’s a private digital call to arms by a mysterious underground group called Mr. Robot (resembling the cybervigilante group Anonymous). They’ve hatched a plan to to concoct a wide-scale economic cyber attack that will result in the single biggest redistribution of wealth and debt forgiveness in history, and recruited Elliot into their organization. The question, and intriguing premise of the series, is whether Elliot can juggle his clean-cut day job, subversive underground hacking and protecting society one cyberterrorist act at a time, or if they will collapse under the burden of his conscience and mental illness.

Humans is a purview into the inevitable future, albeit one that may be creeping on us faster than we want it to. Even if hyper-advanced artificial intelligence is not an imminent reality and our fears might be overblown, the impact of technology on economics and human evolution is a reality we will have to grapple with eventually. And one that must inform the bioethics of any advanced sentient computing technology we create and release into the world. Mr. Robot is a stark reminder of our current present, that cyberterrorism is the new normal, that its global impact is immense, and (as with the case of artificial robots), our advancement of and reliance on technology is outpacing humans’ ability to control it.

ScriptPhD.com was extremely fortunate to chat directly with Humans writers Jonathan Brackley and Sam Vincent about the premise and thematic implications of their show. Here’s what they had to say:

ScriptPhD.com: Is “Humans” meant to be a cautionary tale about the dangers of complex artificial intelligence run amok or a hypothetical bioethical exploration of how such technology would permeate and affect human society?

Jonathan and Sam: Both! On one level, the synths are a metaphor for our real technology, and what it’s doing to us, as it becomes ever more human-like and user-friendly – but also more powerful and mysterious. It’s not so much hypothesising as it is extrapolating real world trends. But on a deeper story level, we play with the question – could these machines become more, and if so, what would happen? Though “run amok” has negative connotations – we’re trying to be more balanced. Who says a complex AI given free rein wouldn’t make things better?

SPhD: I found it interesting that there’s a tremendous range of emotions in how the humans related to and felt about their “synths.” George has a familial affection for his, Laura is creeped out/jealous of hers while her husband Joe is largely indifferent, policeman Peter grudgingly finds his synth to be a useful rehabilitation tool for his wife after an accident. Isn’t this reflective of the range of emotions in how humans react to the current technology in our lives, and maybe always will?

J&S: There’s always a wide range of attitudes towards any new technology – some adopt enthusiastically, others are suspicious. But maybe it’s become a more emotive question as we increasingly use our technology to conduct every aspect of our existence, including our emotional lives. Our feelings are already tangled up in our tech, and we can’t see that changing any time soon.

SPhD: Like many recent works exploring Artificial Intelligence, at the root of “Humans” is a sense of fear. Which is greater – the fear of losing our flaws and imperfections (the very things that make us human) or the genuine fear that the sentient “synths” have of us and their enslavement?

J&S: Though we show that synths certainly can’t take their continued existence for granted, there’s as much love as fear in the relationships between our characters. For us, the fear of how our technology is changing us is more powerful – purely because it’s really happening, and has been for a long time. But maybe it’s not to be feared – or not all of it at least…

Catch a trailer and closer series look at the making of Humans here:

And catch the FULL first episode of Mr. Robot here:

Mr. Robot airs on USA Network with full episodes available online.

Humans premieres on June 28, 2015 on AMC Television (USA) and airs on Channel 4 (UK).

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development. Follow us on Twitter and Facebook. Subscribe to our podcast on SoundCloud or iTunes.

One of Walt Disney’s enduring lifetime legacies was his commitment to innovation, new ideas and imagination. An inventive visionary, Disney often previewed his inventions at the annual New York World’s Fair and contributed many technological and creative breakthroughs that we enjoy to this day. One of Disney’s biggest fascinations was with space exploration and futurism, often reflected thematically in Disney’s canon of material throughout the years. Just prior to his death in 1966, Disney undertook an ambitious plan to build a utopian “Community of Tomorrow,” complete with state-of-the-art technology. Indeed, every major Disney theme park around the world has some permutation of a themed section called “Tomorrowland,” first introduced at Disneyland in 1955, featuring inspiring Jules Verne glimpses into the future. This ambition is beautifully embodied in Disney Picttures’ latest release of the same name, a film that is at once a celebration of ideas, a call to arms for scientific achievement and good old fashioned idealistic dreaming. The critical relevance to our circumstances today and full ScriptPhD review below.

“This is a story about the future.”

With this opening salvo, we immediately jump back in time to the 1964 World’s Fair in New York City, the embodiment of confidence and scientific achievement at a time when the opportunities of the future seemed limitless. Enthusiastic young inventor Frank Walker (Thomas Robinson), an optimistic dreamer, catches the attention of brilliant scientist David Nix (Hugh Laurie) and his young sidekick Athena, a mysterious little girl with a twinkle in her eye. Through sheer curiosity, Frank follows them and transports himself into a parallel universe, a glimmering, utopian marvel of futuristic industry and technology — a civilization gleaming with possibility and inspiration.

“Walt [Disney] was a futurist. He was very interested in space travel and what cities were going to look like and how transportation was going to work,” said Tomorrowland screenwriter Damon Lindelof (Lost, Prometheus). “Walt’s thinking was that the future is not something that happens to us. It’s something we make happen.”

Unfortunately, as we cut back to present time, the hope and dreams of a better tomorrow haven’t quite worked out as planned. Through the eyes of idealistic Casey Newton (Britt Robertson), thrill seeker and aspiring astronaut, we see a frustrating world mired in wars, environmental devastation and selfish catastrophes. But Casey is smart, stubborn and passionate. She believes the world can be restored to a place of hope and inspiration, particularly through science. When she unexpectedly obtains a mysterious pin — which we first glimpsed at the World’s Fair — it gives her a portal to the very world that young Frank traveled to. Protecting Casey as she delves deeper into the mystery is Athena, who it turns out is a very special time-traveling recruiter. She distributes the pins to a collective of the smartest, most creative people, who gather in the Tomorrowland utopia to work and invent free of the impediments of our current society.

Athena connects Casey with a now-aged Frank (George Clooney), who has turned into a cynical, reclusive iconoclastic inventor (bearing striking verisimilitude to Nikola Tesla). Casey and Frank must partner to return to Tomorrowland, where something has gone terribly awry and imperils the existence of Earth. David Nix, a pragmatic bureaucrat and now self-proclaimed Governor of a more dilapidated Tomorrowland, has successfully harnessed subatomic tachyon particles to see a future in which Earth self-destructs. Unless Casey and Frank, aided by Athena and a little bit of Disney magic, intervene, Nix will ensure the self-fulfilling prophesy comes to fruition.

As the co-protagonist of Tomorrowland Casey Newton symbolizes some of the most important tenets and qualities of a successful scientist. She’s insatiably curious, in absolute awe of what she doesn’t know (at one point looking into space and cooing “What if there’s everything out there?”) and buoyant in her indestructible hope that no challenge can’t be overcome with enough hard work and out-of-the-box originality. She loves math, astronomy and space, the hard sciences that represent the critical, diverse STEM jobs of tomorrow, for which there is still a graduate shortage. That she’s a girl at a time when women (and minorities) are still woefully under-represented in mathematics, engineering and physical science careers is an added and laudable bonus. She defiantly rebels against the layoff of her NASA-engineer father and the unspeakable demolition of the Cape Canaveral platform because “there’s nothing to launch.” The NASA program concomitantly faces the tightest operational budget cuts (particularly for Earth science research) and the most exciting discovery possibilities in its history.

The juxtaposition of Nix and Walker, particularly their philosophical conflict, represents the pedantic drudgery of what much of science has become and the exciting, risky brilliance of what it should be. Nix is pedantic and rigid, unable or unwilling to let go of a traditional credo to embrace risk and, with it, reward. Walker is the young, bushy-tailed, innovative scientist that, given enough rejection and impediments, simply abandons their research and never fulfills their potential. This very phenomenon is occurring amidst an unprecedented global research funding crisis — young researchers are being shut out of global science positions, putting innovation itself at risk. Nix’s prognostication of inevitable self-destruction because we ignore all the warning signs before our eyes, resigning ourselves to a bad future because it doesn’t demand any sacrifice from our present is the weary fatalism of a man that’s given up. His assessment isn’t wrong, he’s just not representative of the kind of scientist that’s going to fix it.

“Something has been lost,” Tomorrowland director Brad Bird believes. “Pessimism has become the only acceptable way to view the future, and I disagree with that. I think there’s something self-fulfilling about it. If that’s what everybody collectively believes, then that’s what will come to be. It engenders passivity: If everybody feels like there’s no point, then they don’t do the myriad of things that could bring us a great future.”

Walt Disney once said, “If you can dream it, you can do it.” Tomorrowland‘s emotional call for dreamers from the diverse corners of the globe is the hope that can never be lost as we navigate a changing, tumultuous world, from dismal climate reports to devastating droughts that threaten food and water supply to perilous conflicts at all corners of our globe. Because ultimately, the precious commodity of innovation and a better tomorrow rests with the potential of this group. We go to the movies to dream about what is possible, to be inspired and entertained. Utilizing the lens of cinematic symbolism, this film begs us to engage our imaginations through science, technology and innovation. It is the epitome of everything Walt Disney stood for and made possible. It’s also a timely, germane message that should resonate to a world that still needs saving.

Oh, and the blink-and-you-miss-it quote posted on the entrance to the fictional Tomorrowland? “Imagination is more important than knowledge.” —Albert Einstein.

View the Tomorrowland trailer:

Tomorrowland goes into wide release on May 22, 2015.

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development. Follow us on Twitter and Facebook. Subscribe to our podcast on SoundCloud or iTunes.

Every so often, a seminal film comes out that ends up being the hallmark of its genre. 2001: A Space Odyssey redefined space and technology in science fiction. Star Wars proved sci-fi could provide blockbuster material, while Blade Runner remains the standard-bearer for post-apocalyptic dystopia. A slate of recent films have broached varying scenarios involving artificial intelligence – from talking robots to sentient computers to re-engineered human capacity. But Ex Machina, the latest film from Alex Garland (writer of the pandemic horror film 28 Days Later and the astro-thriller Sunshine) is the cream of the crop. A stylish, stripped-down, cerebral film, Ex Machina weaves through the psychological implications of an experimental AI robot named Ava possessing preternatural emotional intelligence and free will. It’s a Hitchcockian sci-fi thriller for the geek chic gadget-bearing age, a vulnerable expository inquiry into the isolated meaning of “sentience” (something we will surely contend with in our time) and an honest reproach of technology’s boundless capabilities that somehow manages to celebrate them at the same time.

ScriptPhD.com’s enthusiastic review of this visionary new sci-fi film includes an exclusive Q&A with writer and director Alex Garland from a recent Los Angeles screening.

The preoccupation with superior artificial intelligence as a thematic idea is not a recent phenomenon. After all, Frankenstein is one of the pillars of science fiction – an ode to hypothetical human engineering gone awry. Terminator and its many offshoots gave rise to robotics engineering, whether as saviors or disruptors of humanity. But over the last 16 months, a proliferation of films centered around the incorporation of artificial intelligence in the ongoing microevolution of humanity has signaled a mainstream arrival into the zeitgeist consciousness. 2014 was highlighted with stylish and ambitious but ultimately overmatched digital reincarnation film Transcendence to the understated yet brilliant digital love story Her to the surprisingly smart Disney film Big Hero 6. This year amplifies that trend, with Avengers: Age of Ultron and Chappie marching out robots Elon Musk could only dream about among many other later releases. Wedged in-between is Ex Machina, taking its title from the Latin Deus Ex Machina (God from the machine), a film that prefers to focus on the bioethics and philosophy of scientific limits rather than the razzle-dazzle technology itself. There is still a tendency for sci-fi films concerning AI to engross themselves in presenting over-the-top science, with ensuing wholesale consequences based on theoretical technology, which ultimately hinders storytelling. Ex Machina is a simple story about two male humans, a very advanced-intelligence generated AI robot named Ava, confined in a remote space together, and the life-changing consequences that their interactions engender as a parable for the meaning of humanity. It will be looked back on as one of the hallmark films about AI.

When computer programmer Caleb Smith (Domhall Gleeson) wins an exclusive private week with his search engine company’s CEO Nathan Bateman (Oscar Isaac) it seems like a dream come true. He is helicoptered to the middle of a verdant paradise, where Nathan lives as a recluse in a locked-down, self-sufficient compound. Only Nathan plans to let Caleb be the first to perform a Turing Test on an advanced humanistic robot named Ava (Alicia Vikander). (Incidentally, the technology of creating a completely new robot for cinema was a remarkable process, as the filmmakers discussed in-depth in the New York Times.) The opportunity sounds like a geek’s dream come true, only as the layers slowly peel back, it is apparent that Caleb’s presence is no accident; indeed, the methodology for how Nathan chose him is directly related to the engineering of Ava. Nathan is, depending on your viewpoint, at best a lonely eccentric and at worst an alcoholic lunatic.

For two thirds of the movie, tension is primarily ratcheted through Caleb’s increasingly tense interviews with Ava. She’s smart, witty, curious and clearly has a crush on him. Is something like Ava even possible? Depending on who you ask, maybe not or maybe it already happened. But no matter. The latter third of the movie provides one breathtaking twist after another. Who is testing and manipulating whom? Who is really the “intelligent being” of the three? Are we right to be cautionary and fear AI, even stop it in its tracks before it happens? With seemingly anodyne versions of “helpful robots” already in existence, and social media looking into implementing AI to track our every move, it may be a matter of when, not if.

The brilliance of Alex Garland’s sci-fi writing is his understanding that understated simplicity drives (and even heightens) dramatic tension. Too many AI and techno-futuristic films collapse under the crushing weight of over-imagined technological aspirations, which leave little room for exploring the ramifications thereof. We start Ex Machina with the simple premise that a sentient, advanced, highly programmed robot has been made. She’s here. The rest of the film deftly explores the introspective “what now?” scenarios that will grapple scientists and bio-ethicists should this technology come to pass. What is sentience and can a machine even possess self-awareness? Is their desire to be free of the grasp of their creators wrong and should we allow it? Most importantly, is disruptive AI already here in the amorphous form of social media, search history and private data collected by big technology companies?

The vast majority of Ex Machina consists of the triumvirate of Nathan, Caleb and Ava, toggling between scenes with Nathan and Caleb and Caleb interviewing (experimenting on?) Ava between a glass facade. The progression of intensity in the numbered interviews that comprise the Turing Test are probably the most compelling of the whole film, and nicely set-up the shocking conclusion. In its themes of the human/AI dichotomy and dialogue-heavy tone, Ex Machina compares a lot to last year’s brilliant sci-fi film Her, which rightfully won Spike Jonze the Oscar for Best Original Screenplay. In the former, a lonely professional letter writer becomes attached to and eventually falls in love with his computer operating system Samantha. Eventually, we see the limitations of a relationship void of human contact and the peculiar idiosyncrasies that make us so distinct, the very elusive elements that Samantha seeks to know and understand. (Think this scenario is far off? Many tech developers feel it is not only inevitable but not too far away.To that degree, both of these films show two kinds of sentient future technology chasing after human-ness, yearning for it, yet caution against a bleak future where they supplant it. But whereas Her does so in a sweetly melancholy sentimental fashion, Ex Machina plants a much darker, psychologically prohibitive conclusion.

It turns out that the most terrifying scenario isn’t a world in which artificial intelligence disrupts our lives through a drastic shift in technology. It’s a world in which technology seamlessly integrates itself into the lives we already know.

View the official Ex Machina trailer here:

Alex Garland, writer and director of Ex Machina, stayed after a recent Los Angeles press screening to give an insightful, profound question and answer session about the artificial intelligence as portrayed in the film and its relationship to the recent slew of works depicting interactive technology.

Ava [the robot created by Nathan Bateman] knew what a “good person” was. Why wasn’t she programmed by Nathan to just obey the commandments and not commit certain terrible acts that she does in the film?

AG: The same reason that we aren’t programmed that way. We are asked not to [sin] by social conventions, but no one instructs or programs us not to do it. And yet, a lot of us do bad things. Also, I think what you’re asking is – is Ava bad? Has she done something wrong? And I think that depends on how you choose to look at the movie. I’ve been doing stories for a while, and you hand the story over and you’ve got your intentions but I’ve been doing it for long enough to know that people bring their own [bias] into it.

The way I saw this movie was it was all about this robot – the secret protagonist of the movie. It’s not about these two guys. That’s a trick; an expectation based on the way it’s set up. And if you see the story from her point of view, if her is the right word, she’s in a prison, and there’s the jailer and the jailer’s friend and what she wants to do is get out. And I think if you look at it from that perspective what she does isn’t bad, it’s practical. Yes, she tricks them, but that’s okay. They shouldn’t have been dumb. If you arrive in life in this place, and desire to get out, I think her actions are quite legitimate.

So, that’s a very human-like quality. So let’s say that you’re confronted with a life or death situation with artificial intelligence. Do you have any tricks that you would use [to survive]?

AG: If I’m hypothetically attacked by an AI, I don’t know… run. I think the real question is whether AI is scary. Should we fear them? There’s a lot of people who say we should. Some smarter people than me such as Elon Musk, Stephen Dawkins, and I understand that. This film draws parallels with nuclear power and [Oppenheimer’s caution]. There’s a latent danger there in both. Yet, again, I think it depends on how you frame it. One version of this story is Frankenstein, and that story is a cautionary tale – a religious one at that. It’s saying “Man, don’t mess with God’s creationary work. It’s the wrong thing to do.”

And I framed this differently in my mind. It’s an act of parenthood. We create new conciousnesses on this planet all the time – everyone in this room, everyone on the planet is a product of other people having created this consciousness. If you see it that way, then the AI is the extension of us, not separate from us. A product of us, of something we’ve chosen to do. What would you expect or want of your child? At the bare minimum, you’d want for them to outlive you. The next expectation is that their life is at least as good as yours and hopefully better. All of these things are a matter of perspective. I’m not anti-AI. I think they’re going to be more reasonable than us, potentially in some key respects. We do a lot of unreasonable stuff and they may be fairer.

On the subject of reproduction, in this film, Ava was anatomically correct. Had it been a male, would he have been likewise built correctly?

AG: If you made the male AI in accordance with the experiment that this guy is trying to conduct, then yes. This film is an “ideas movie.” Sometimes it’s asking a question and then presenting an answer, like “Does she have empathy?” or “Is she sentient?”. Sometimes, there isn’t an answer to the question, either because I don’t know the answer or because no one does. The question you’re framing is not “Can you [have sex] with these AI?” it’s “Where does the gender reside?” Where does gender exist in all of us. Is it in the mind, or in the body? It would be easy to construct an argument that Ava has no gender and it would seem reasonable in many respects. You could take her mind and put it in a male body and say “Well, nothing is substantially changed. This is a cosmetic difference between the two.” And yet, then you start to think about how you talk about her and how you perceive her. And to say “he” of Ava just seems wrong. And to say “it” seems weirdly disrespectful. And you end up having this genderless thing coming back to she.

In addition, if you’re going to say gender is in the mind, then demonstrate it. That’s the question I’m trying to provoke. When they have that conversation halfway through the film, these implicit questions, if gender is in the mind, then what is it? Does a man think differently from a woman? Is that really true? Think of something that a man would always think, and you’ll find a man that doesn’t always think that, and you’ll find a woman that does. These are the implicit questions in the film. They don’t all have answers. The key thing about the gender thing isn’t about who is having sex with whom. It’s that this young man is tasked with thinking about what’s going on inside of this machine’s head. That’s his job is to figure that out. And at a certain point he stops thinking about her and he gets it wrong. That’s the issue – why does he stop thinking about it? If the plot shifts in this worked on the audience or any of you in the same way as they worked on the young man, why was that?

Was one of your implicit messages in the film for people to be more conscientious about what they’re sharing on the internet, whether in their searches or social media, and thereby identifying their interests “out there” and how that might be potentially used?

AG: Yes, absolutely. It’s a strange thing, what zeitgeist is. Movies take ages [to make] sometimes – like two and a half years at least. I first wrote this script about four years ago. And then, I find out as we go through production that we’re actually late to the party. There are a whole bunch of films about AI – Transcendance, Automator, Big Hero 6, Age of Ultron [coming out next month], Chappie. Why is that? There hasn’t been any breakthrough in AI, so why are all these people doing this at the same time? And I think it’s not AIs, I think it’s search engines. I think it’s because we’ve got laptops and phones and we, those of us outside of tech, don’t really understand how they work. But we have a strong sense that “they” understand how “we” work. They anticipate stuff about us, they target us with advertising, and I think that makes us uneasy. And I think that these AI stories that are around are symptomatic of that.

That bit in the film about [the dangers of internet identity], in a way it obliquely relates to Edward Snowden, and drawing attention to what the government is doing. But if people get sufficiently angry, they can vote out the government. That is within the power of an electorate. Theoretically, in capitalist terms, consumers have that power over tech companies, but we don’t really. Because that means not having a mobile phone, not having a tablet, a computer, a credit card, a television, and so on. There is something in me that is worried about that. I actually like the tech companies, because I think they’re kind of like NASA in the 1960s. They’re the people going to the moon. That’s great – we wanted to go to the moon. But I’m also scared of them, because they’ve got so much power and we tend not to cope well with a lot of power. So yes, that’s all in the film.

You mentioned Elon Musk earlier, who looks a little bit like [Google co-founder] Sergei Brin. Which tech executive would you say CEO Nathan Batemn is most modeled after?

AG: He wasn’t exactly modeled after an exec. He was modeled more like the companies in some respect. All that “dude, bro” stuff. I sometimes feel that’s what they’re doing. Not to generalize, but it’s a little bit like that – we’re all buddies, come on, dude. While it’s rifling through my wallet and my address book. It’s misleading, a mixed message. I don’t want to sound paranoid about tech companies. I do really like them, I think they’re great. But I think it’s correct to be ambivalent about them. Because anything which is that powerful and that unmarshalled you have to be suspicious of, not even for what we know they’re doing but for what they might do. So, Nathan is more [representative of] a vibe than a person.

For someone equally as scared of AI as Alex is of tech companies, what is the gap between human intelligence and AI intelligence that exists today? How long before we have AI as part of our daily lives?

AG: One of the great pleasures of working on this film was contacting and discussing with people who are at the edge of AI research. I don’t think we’re very close at all. It depends on what you’re talking about. General AI, yes, we’re getting closer. Sentient machines, it’s not even in the ballpark. It’s similar in my mind to a cure for cancer. You can make progress and move forward, but sometimes by going forward it highlights that the goal has receded by complexity. I know Ray Kurtzweil makes some sort of quantified predictions – in 20 years, we’ll be there. I don’t know how you can do that. He’s a smart guy, maybe he’s right. As far as I can tell, in talking to the people who are as close to knowing [about the subject] as I can encounter, it’s something that may or may not happen. And it will probably take a while.

One of the things that’s always bothered me about the Turing Test is that it’s not seeking to know whether or not the thing you’re dealing with is an artificial intelligence. It’s – can you tell that it is? And that’s always bothered me as a kind of weird test. You have a 20,000 question survey, and in the end this one decision comes from a binary point of view. It seems almost flawed.

AG: Yes, you’re completely right. Apart from the fact that it was configured quite a long time ago, it’s primarily a test to see if you can pass the Turing Test. It doesn’t carry information about sentience or potential intelligence. And you could certainly game it. But, it’s also incredibly difficult to pass. So in that respect it’s a really good test. It’s just not a test of what it’s perceived to be a test of, typically. This [experiment in the movie] was supposed to be like a post-Turing Turing Test. The guy says she passed with blind controls, he’s not interested in whether she’ll pass. He’s not interested in her language capacity, which is comparable to a chess computer that wants to win at chess, but doesn’t even know whether it’s playing chess or that it’s a computer. This is the thing you’d do after you pass the Turing Test. But I totally agree with everything you said.

In your research, is there a test that’s been developed that is the reverse of the Turing Test, that seeks to answer whether, in the face of so much technology development, we’ve lost some of our innate human-ness? Or that we’re more machine like?

AG: I think we are machine-like. As far as I know, no test exists like that. The argument at the heart of these things is: is there a significant difference between what a machine can do and what we are? I think how I see this is that we sometimes dignify our conciousness. We make it slightly metaphysical and we deify it because it’s so mysterious to us. An we think, are computers ever going to get up to the lofty heights where we exist in our conciousness? And I suspect that we should be repositioning it here, and we overstate us, in some respects. That’s probably the opposite of what you want to hear.

Do you think that some machine-like quality predates the technology?

AG: I do, yes. I suspect all our human aspects are through evolution, that’s how I think we got here. I can see how conciousness arises from needing to interact in a meaningful and helpful way with other sentient things. Our language develops, and as these things get more sophisticated, conciousness becomes more useful and things that have higher conciousness succeed better. Also, I heard someone talk about conciousness the other day and they were saying “One day, it’s possible that elephants will become sentient.” And that’s a really good example of how we misunderstand sentience. Elephants are already sentient. If you put a dog in front of a mirror, it recognizes its own reflection. It’s self-aware. It knows it’s not looking at another dog. So I put us on that spectrum.

Pertaining to that question, there’s a [critical] moment in the movie where Caleb cuts himself in front of a mirror to make sure that he’s bleeding. And I was going to ask if that’s symbolic of that evolution where conciousness can be undifferentiated between a human and a machine? I was wondering if that scene is a subtle hint that you don’t really know whether you’re the one that is being tested or you’re the tester?

AG: There’s two parts [to that scene]. One is film audiences are literate. I kind of assume that everyone who’s seen that has seen Blade Runner. So they’re going to be imagining to themselves, it’s not her [that is the AI] it’s him. He’s the robot. Here’s the thing. If someone asks of you, here’s a machine, test that machine’s conciousness, tell me if it’s concious or not, it turns out to be a very difficult thing to do. Because [the machine] could act convincingly that it’s concious, but that wouldn’t tell you that it is. Now, once you know that, that actually becomes true of us. You don’t know I’m concious. You think I’m probably concious, you’re not really questioning it. But you believe you are concious, and because I’m like you, I’m another human, you assume I’ve got it. But I’m doing anything that empirically demonstrates that I am concious. It’s an act of faith. And once you know that, you’ve figured that out about the machine and now you can figure it out about the other person. Weirdly, then you can ask it of yourself. That’s where the diminished sense of conciousness comes into it. The things that I believe are special about me are the things I’m feeling – love, fear. And then you think about electrochemicals floods in your brain and the things we’ve been taught and the things we’ve been born with and our behavior patterns and suddenly it gets more and more diminished. To the point that you can think something along the lines of “Am I like a complicated plant that thinks it’s a human?” It’s not such an unreasonable question. So cut your arm and have a look!

In thinking about being a complicated plant, that sounds very isolating. Nathan was really isolated in the movie as well. Do you think that this is indicative of where we’re going with our devices and internet and social media being our social outlet rather than actually socializing? Is AI taking us down that path of isolation?

AG: It may or may not. That could be the case. I’m not on Twitter, I’ve never been on Facebook, I’m not really too [fond of] that stuff. From the outside looking in, it looks like that’s the way people communicate – maybe in a limited way, but in a way I don’t really know. The thing about Nathan is we’re social animals, and our behavior is incredibly modified by people around us. And when we’re removed from modification, our behavior gets very eccentric very fast. I think of it like a kid holding on to a balloon and then they let it go and in a flash it’s gone. I know this because my job is I’m a writer and if I’m on a roll, I can spend six days where I don’t leave the house, I barely see my kids in the corridor, but I’m mainly interested in the fridge and the computer. And I get weird, fast. It’s amazing how quickly it happens. I think anyone who’s read Heart of Darkness or seen the adaptation Apocalypse Now, [Nathan] is like this character Kurtz. He spends too much time upriver, too much time unmodified by the influences that social interactions provide.

Ex Machina goes into wide release in theaters on April 10, 2015.

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development. Follow us on Twitter and Facebook. Subscribe to our podcast on SoundCloud or iTunes.

On February 28, 1998, the revered British medical journal The Lancet published a brief paper by then-high profile but controversial gastroenterologist Andrew Wakefield that claimed to have linked the MMR (measles, mumps and rubella) vaccine with regressive autism and inflammation of the colon in a small case number of children. A subsequent paper published four years later claimed to have isolated the strain of attenuated measles virus used in the MMR vaccine in the colons of autistic children through a polymerase chain reaction (PCR amplification). The effect on vaccination rates in the UK was immediate, with MMR vaccinations reaching a record low in 2003/2004, and parts of London losing herd immunity with vaccination rates of 62%. 15 American states currently have immunization rates below the recommended 90% threshold. Wakefield was eventually exposed as a scientific fraud and an opportunist trying to cash in on people’s fears with ‘alternative clinics’ and pre-planned a ‘safe’ vaccine of his own before the Lancet paper was ever published. Even the 12 children in his study turned out to have been selectively referred by parents convinced of a link between the MMR vaccine and their children’s autism. The original Lancet paper was retracted and Wakefield was stripped of his medical license. By that point, irreparable damage had been done that may take decades to reverse.

How could a single fraudulent scientific paper, unable to be replicated or validated by the medical community, cause such widespread panic? How could it influence legions of otherwise rational parents to not vaccinate their children against devastating, preventable diseases, at a cost of millions of dollars in treatment and worse yet, unnecessary child fatalities? And why, despite all evidence to the contrary, have people remained adamant in their beliefs that vaccines are responsible for harming otherwise healthy children, whether through autism or other insidious side effects? In his brilliant, timely, meticulously-researched book The Panic Virus, author Seth Mnookin disseminates the aggregate effect of media coverage, echo chamber information exchange, cognitive biases and the desperate anguish of autism parents as fuel for the recent anti-vaccine movement. In doing so, he retraces the triumphs and missteps in the history of vaccines, examines the social impact of rejecting the scientific method in a more broad perspective, and ways that this current utterly preventable public health crisis can be avoided in future scenarios. A review of The Panic Virus, an enthusiastic ScriptPhD.com Editor’s Selection, follows below.

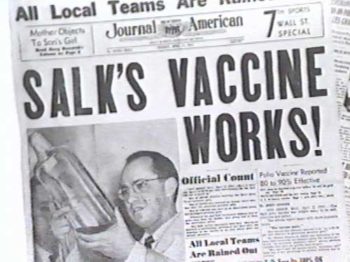

Such fervent controversy over inoculating young children for communicable diseases might have seemed unimaginable to the pre-vaccine generations. It wasn’t long ago, Mnookin chronicles, that death and suffering at the hands of diseases like polio and small pox were the accepted norm. In 18th Century Europe, for example, 400,000 people per year regularly died of small pox, and it caused one third of all cases of blindness. So desperate were people to avoid the illnesses’ ravages, that crude, rudimentary inoculation methods were employed, even at the high risk of death, to achieve life-long immunity. A 1916 polio outbreak in New York City, with fatality rates between 20 and 25 percent, frayed nerves and public health infrastructure to the point of near-anarchy. As the disease waxed and waned in outbreaks throughout the decades that followed, distraught parents had no idea about how to protect their children, who were often far more susceptible to fatality than adults. By the time Jonas Salk’s polio vaccine breakthrough was announced as “safe, effective and potent” on April 12, 1955, pandemonium broke out. “Air raid sirens were set off,” Mnookin writes. “Traffic lights blinked red; churches’ bells rang; grown men and women wept; schoolchildren observed a moment of silence.” Salk’s discovery was hailed as “one of the greatest events in the history of medicine.”

Mnookin doesn’t let scientists off the hook where vaccines are concerned, however, and rightfully so. Starting around World War II, with advances such as the cowpox and polio vaccines, along with the dawning of the Antibiotics Age, eradicating death and suffering from communicable diseases and bacterial infections, a hubris and sense of superiority began to creep into the scientific establishment, with dangerous consequences. Fearing the threat of biological warfare during World War II, a 1941 hastily-constructed US military campaign to vaccinate all US troops against yellow fever resulted in batches contaminated with Hepatitis B, resulting in 300,000 infections and 60 deaths. The first iteration of Salk’s polio vaccine was only 60-90% effective before being perfected and eventually replaced by the more effective Sabin vaccine. Furthermore, dozens of children who had received doses from the first batch of vaccines were paralyzed or killed due to contaminated vaccines that had failed safety tests. In 1976, buoyed by the death of a soldier from a flu virus that bore striking genetic similarity to the 1918 Spanish flu epidemic strain, President Gerald Ford instituted a nation-wide mass vaccination initiative against a “swine flu” epidemic. Unfortunately, although 40 million Americans were vaccinated in three months, 500 developed symptoms of Guillain-Barré syndrome (30 died), seven times higher than would normally be expected as a rare side effect of vaccination. Many people feel that the scars of the 1976 fiasco have incurred a permanent distrust of the medical establishment and have haunted public health influenza immunization efforts to this day.

These black marks on the otherwise miraculous, life-saving history of vaccine development not only instilled a gradual mistrust in public health officials, but laid the groundwork for the incendiary autism-vaccine scandal. The only missing components were a proper context of panic, a snake oil salesman and a compliant media willing to spread his erroneous message.

Enter the autism epidemic and Andrew Wakefield’s hoax. Because this seminal event had such a profound effect on the formation and proliferation of the current anti-vaccine movement, it is chronicled in far greater detail than our introduction above. From precursor incidents that ripened the potential for coercion to the Wakefield’s shoddy methodology and the naive medical community that took him at his word, Mnookin weaves through this case with well-researched scientific facts, interesting interviews and logic. A large chunk of the book is ultimately devoted to the psychology of what the anti-vaccine movement really is: a cognitive bias and a willingness to stay adamant in the belief that vaccines cause harm despite all evidence to the contrary. “If you assume,” he writes, “as I had, that human beings are fundamentally logical creatures, this obsessive preoccupation with a theory that has for all intents and purposes been disproved is hard to fathom. But when it comes to decisions around emotionally charged topics, logic often takes a back seat to a set of unconscious mechanisms that convince us that it is our feelings about a situation and not the facts that represent the truth.”

Given this blog’s objective to cover science and technology in entertainment and media, it would be disingenuous to write about the anti-vaccine movement without recognizing the implicit role played by the media and entertainment industries in exacerbating the polemic. By lending a voice to the anti-vaccine argument, even in a subtle manner or in a journalistic attempt to “be fair to the other side,” over time, an echo chamber of lies turned into an inferno. In 1982, an hour-long NBC documentary called DPT: Vaccine Roulette aired, overemphasizing rare side effects in babies from vaccinations to a nation of alarmed parents and completely undermining their benefits. It was a propaganda piece, but an important hallmark for what would come later. A 2008 episode of the popular ABC hit show Eli Stone irresponsibly aired anti-vaccination propaganda involving a lawyer questioning a pharmaceutical company that manufactures vaccines due to the even then-debunked link to autism. For several recent years, actress and Playboy bunny Jenny McCarthy (who is given an entire chapter by Mnookin) became a tireless advocate against vaccinations, believing that they gave her son autism. She didn’t have any scientific proof for this, but was nevertheless given a platform by everyone from Larry King on CNN to a fawning Oprah Winfrey.

As it turns out, McCarthy’s son never even had autism, but rather a very rare and treatable neurological disorder. In a self-penned editorial for the Chicago Sun-Times, she has officially retroactively denied her anti-vaccine stance, and says she simply wants “more research on their effectiveness.” An extremely sympathetic 2014 eight-page Washington Post magazine article profile of prominent anti-vaccine activist Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. (who believes in the link between vaccines and autism) repeated his talking points numerous times throughout. This, among an endless cycle of interviews and appearances by defiant anti-vaccine proponents, given equal air time side-by-side with frustrated scientists, as if both positions were somehow viable, and worthy of journalistic debate. Once the worm was out of the can, no amount of rational discourse could temper the visceral antipathy that had been created. This is irresponsible, dangerous and flat-out wrong. When the public is confused about an esoteric issue pertaining to science, medicine or technology, influencers in the public eye cannot perpetuate misinformation.

Despite the unanimous medical repudiation of Wakefield’s fraudulent methods and conclusions and the retraction of his Lancet paper, an irreversible and insidious myth had begun permeating, first among the autism community, then spreading to proponents of organic and holistic approaches to health and finally, to mainstream society. In the aftermath of the controversy, epidemiological studies debunking the autism-vaccination “link,” combined with a growing disease crisis, have forced the largest US-based autism advocacy organization to reverse its stance and fully endorse vaccination to a still-divided community. Wakefield remains more defiant than ever, insisting to this day that his research was valid, attempting to sue the British journalism outlet that funded the inquiry into his fraud and peddling holistic treatments for autism as well as his “alternative” vaccine. Sadly, the public health ramifications have nothing short of disastrous, with a dangerous recurrence of several major childhood diseases.

A few examples of the many systemic casualties of the anti-vaccination movement (many occurring just since the publication of Mnookin’s book):

•A summary from the American Medical Association about the nascence of the measles crisis in 2011, when the US saw more measles cases than it had in 15 years

•Immunization rates falling so low that schools in some communities are being forced to terminate personal exemption waivers and, in some cases, legally mandated immunization for public school attendance

•California’s worst whooping cough epidemic in 70 years.

•Most recently, a measles outbreak at Disneyland, resulting in 26 cases spread across four states, after an unvaccinated woman visited the theme park

•Anti-vaccine hysteria has spread to Europe, which has had a measles rise of 348% from 2013 to 2014 (and growing), along with an alarming resurgence of pertussis

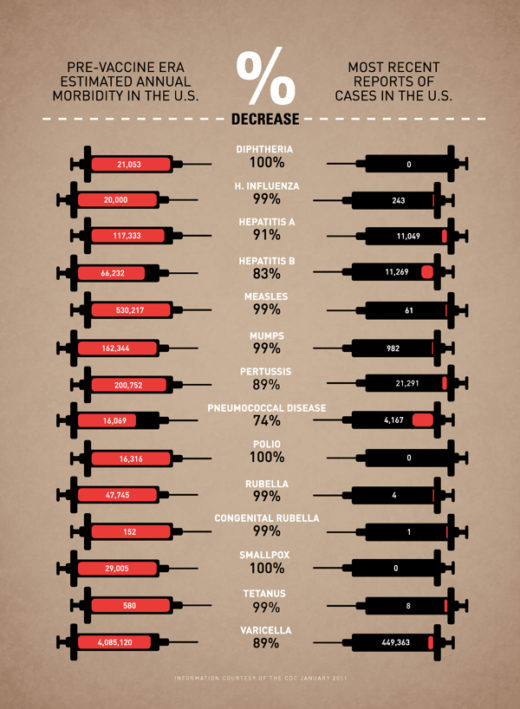

The scientific evidence that vaccines work is indisputable, and as the below infographic summarizes, their impact on morbidity from communicable diseases is miraculous. Sadly, now that the anti-vaccine movement has streamlined into the general population, anxious parents are conflicted as to whether vaccinating is the right choice for their children. We must start by going back to the basics of what a vaccine actually is and how it works. Next, we must reiterate the critical importance that maintaining herd immunity above 92-95% plays in protecting not only those too young or immunocompromised to be vaccinated, but even fully vaccinated populations. If all else fails, try emailing skeptical friends and family a clever graphic cartoon that breaks down digestible vaccine facts. Simply put: getting vaccinated is not a personal choice, it’s a selfish and dangerous choice.

The Panic Virus is first and foremost an incredibly entertaining, well-written narrative of the dawn of an anti-vaccine phenomenon which has reached a critical mass. It is also an important case study and cautionary tale about how we process and disseminate information in the age of the Internet and access to instant information. It is also an indictment on a trigger-happy, ratings-driven, sensationalist media that reports “news” as they interpret it first, and bother to check for facts later. In the case of the anti-vaccine movement of the last few years, the media fueled the fire that Andrew Wakefield started, and once a gaggle of angry, sympathetic parents was released, it was difficult (if-near impossible) to undo the damage. This type of journalism, Mnookin writes, “gives credence to the belief that we can intuit our way through all the various decisions we need to make in our lives and it validates the notion that our feelings are a more reliable barometer of reality than the facts.” Sadly, the autism-vaccine panic movement is not an outlying incident, but rather a disconcerting emblem of a growing anti-science agenda. The UN just released its most dire and alarming report ever issued on man-made climate change impacts, warning that temperature changes and industrial pollution will affect not just the environment, extreme weather events and coastal cities, but even the stability of our global economy itself. Immediate rebuttals from an influential lobbying group tried to undermine the majority of the scientists’ findings. So toxic is the corporate and political resistance to any kind of mitigating action, that some feel we need a technological or political miracle to stave off a certain environmental crisis. At a time when physicists are serious debate on evolution versus creationism and thousands of public schools across the United States use taxpayer funds to teach creationism in the classroom.

Mnookin’s book is an important resource and conversation starter for scientists, researchers and frustrated physicians as they carve out talking points and communication strategies to establish a dialogue with the public at large. When young parents have questions about vaccines (no matter how erroneous or ill-informed), pediatricians should already have materials for engaging in a positive, thoughtful discussion with them. When scientists and researchers encounter anti-science proclivities or subversive efforts to undermine their advocacy for a pressing issue, they should be armed with powerful, articulate communicators — ready and willing to deliberate in the media and convey factual information in an accessible way. When Jenny McCarthy and a gaggle of new-age holistic herbologists were peddling their “mommy instincts” and conspiracy theories against vaccines, far too many scientists and physicians simply thought it was beneath them to even engage in a discussion about something whose certainty and proof of concept was beyond reproach. Now, the newest polling suggests that nothing will change an anti-vaxxer’s mind, not even factual reasoning. Going forward, regardless of the issue at hand, this type of response can never happen again. The cost of complacency or arrogance is nothing short of life or death.

The Panic Virus by Seth Mnookin is currently available on paperback and Kindle wherever books are sold. For further reading on how to deal with the complexities of the anti-vaccine movement aftermath, we suggest the recent book On Immunity: An Inoculation by Northwestern University lecturer Eula Bliss.

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development. Follow us on Twitter and Facebook. Subscribe to our podcast on SoundCloud or iTunes.