There is grandeur in this view of life, with its several powers, having been originally breathed into a few forms or into one; and that, whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved.

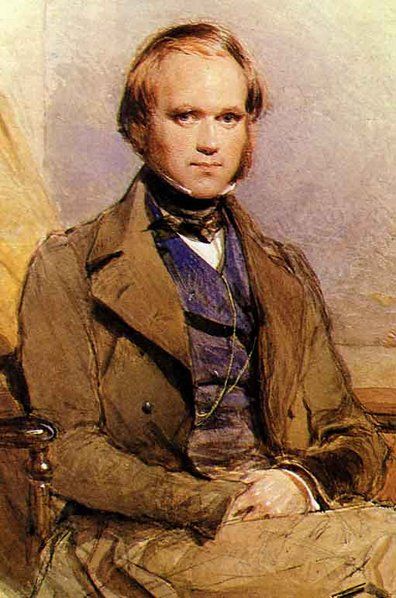

Charles Darwin’s postscript to perhaps the greatest work of biology ever recorded, The Origin of Species, ignited an acrimonious debate about science, religion, the mutual exclusivity thereof, and where we come from. 150 years later, as we celebrate the anniversary of Darwin’s monumental scientific achievement, it is a debate that has yet to abate. Regardless

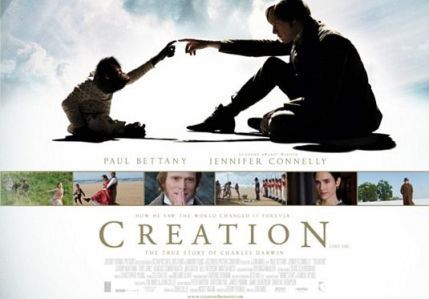

of what stance one takes on evolution and natural selection, fascination with the life and times of this inimitable figure is undeniable. A new biopic, Creation, delves into the dichotomy of Darwin the naturalist and family man, the disapproval he faced from a devotedly Christian wife, and the inner anguish he faced in whether to publish his findings. ScriptPhD.com’s Stephen Compson was recently treated to a private screening of the film and had the extraordinary opportunity to sit down with Darwin’s great-great-grandson Randal Keynes, whose Charles Darwin biography the movie was based on. For our exclusive content, please click “continue reading.”

REVIEW: Creation

ScriptPhD.com Grade: A-

Creation tells the biographical story of Charles Darwin struggling to complete his opus: On the Origin of Species. The screenplay was adapted from Darwin’s great-great grandson Randal Keynes’s book Annie’s Box. Paul Bettany stars as the father of evolution, with his real-life spouse Jennifer Connelly portraying the devoutly religious Emma Darwin. Creation is not the story you think it is, especially if you’re of a mind to burn books along with anyone who tries to rub your nose in empirical evidence. This Darwin is immediately likeable and sympathetic because he’s tortured by his findings. While his persecuted-scientist friends urge him to publish and show that lousy church once and for all, Charles must first deal with a domestic dispute two decades in the making and lay to rest a daughter (Annie) whose death he blames on himself.

The opening is a series of coalescent images: particles in space gaining gravitational momentum transitioning to cells colliding under a microscope, becoming fish swimming together in a bait ball. As we move up the food chain, it’s immediately apparent that there’s a capable hand guiding the lens. This is director Jon Amiel’s most visually stunning work to date, and its vibrancy contrasts with the somewhat cold Victorian setting to give us a front seat in Darwin’s inner eye. The story jumps about in time and setting. Annie’s ghost haunts Darwin through the draft like an editor with a PhD. He tells of his Galápagos adventures as bedtime stories to his children, but it’s clear even to his youngest that Charles favors Annie over her siblings. His guilt is immense, as though by articulating the principle of natural selection he has allowed his favorite child to succumb to it. And so the scientist is forced to confront in the most painful way possible the cold ramifications of his findings. Only by laying Annie to rest and reuniting with his religious wife can he publish his findings. This is thematic film-making at its best, the centuries-old debate over Darwin’s findings personified by immediately human performances.

There’s another layer to this story about science and religion. Darwin argues with his wife about the superiority of science while ingesting doctor-prescribed laudanum for an upset stomach. Laudanum is a powerful opiate that also influenced the works of Lewis Carroll and Samuel Taylor Coleridge (we must imagine briefly the time when critics will look back at our generation and think to themselves, sweet Darwin, they all drank so much coffee). Also, both Charles and his daughter are treated for illness by having torrents of cold water poured onto them, as this was supposed to be the cutting edge of medical science. Here is one of history’s most respected scientists giving and receiving treatments that must have been detrimental at best. It is an interesting and subtle note: that science is not always so objective, that both doctors and ministers haven’t yet had their last word, and the only ones we can be sure are wrong are the polemicists.

The official studio notes describe the film as “Part psychological thriller and part heart-wrenching love story,” which is a typically superfluous press packet way of saying it’s a drama. You wouldn’t expect a scientist’s biopic to be filled with such vibrant themes and images, or noteworthy performances, but Creation has both. Jennifer Connelly’s spoken pieces are heart-wrenching, but she is at her most violent when she sits in front of the piano, damning her husband with every note like Madame Defarge knitting a guillotine roll-call. Though the high drama occasionally stretches dangerously thin, the married stars bring a natural chemistry that keeps the dough from tearing.

Creation is a quiet film released on the year marking the bicentennial of Darwin’s birth and the 150th anniversary of his seminal work. Rarely does a film confront controversy with so balanced and nuanced an account. Both sides will find their talking points, but the characters are so rich you might just forget about keeping score. Yes, it’s a story about a scientist, but it’s a lot better as a story about a man struggling to tell right from wrong and keep his family together. Then at the end—Spoiler Alert!—this man just happens to publish the theory of evolution.

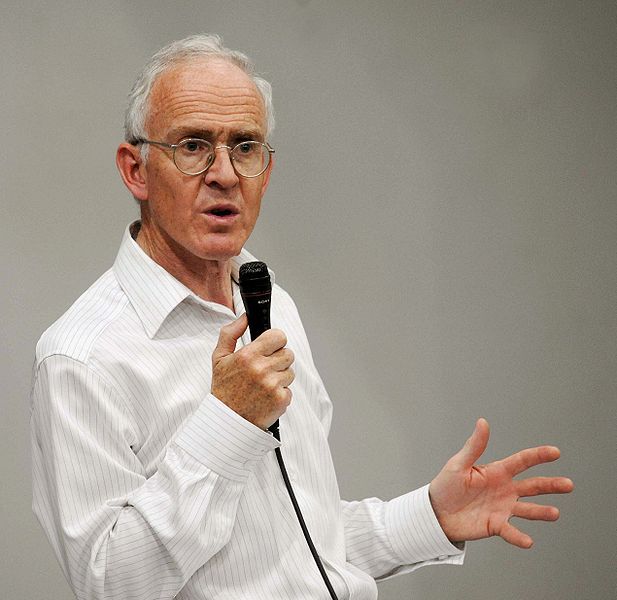

Exclusive ScriptPhD.com Interview With Randal Keynes:

Randal Keynes is the great-great grandson of Charles Darwin and author of the biography Creation: Darwin, His Daughter, and Human Evolution, on which the movie is based. When I arrived at his hotel, I was informed that the interview had to be postponed for an hour because Mr. Keynes was at a Twitter party. I must confess that I’ve fallen behind in my grasp of Twitter-speak, but it sounded to me like I was waiting while he sat upstairs in his underwear updating his feed. During the interview, I would often catch Mr. Keynes staring lewdly at the overgrowth of hair sprouting out the top of my shirt, and when I asked him to focus he sipped deeply from his red wine and went back to tweeting. I’m kidding about the chest hair. But not the Twitter party.

ScriptPhD.com: Tell us how you found the item that inspired this book about Darwin, his daughter Annie’s writing box.

Randal Keynes: For most of my life I took very little interest in Darwin, but about ten years ago I was asked if I could help the organization that opens the [Darwin] house to the public. They wanted information about how Darwin lived with his family. My father had inherited a big chest of drawers from his mother, Darwin’s granddaughter, and in the bottom corner of this chest I found this writing case, and in it there was a folded piece of paper with Darwin’s handwriting: “Annie’s illness.” It seemed to be a note that he had made of the treatments he gave her every morning and how she reacted to it.

SPhD: So he was actually treating his daughter himself?

RK: And this was the extraordinary point. It didn’t fit with my idea of the great scientist on his pinnacle. I found a character that was clearly the real Darwin, because he and his wife Emma were so devoted to Annie: she helped the two of them, keeping them cheerful, helping Darwin with his science. So her father, distressed as he was with all the difficulties of his theory, had to come to terms with her death as well. I found that much of his thinking about human nature one could link with his experience, his love for his wife, the pain of Annie’s illness, his desperation to keep her alive, his sense of emptiness when she died, and coming to terms with the memory. That offered a view of Darwin that was very different. People usually think of tooth and claw, the struggle for existence, life without purpose. I discovered a more human Darwin.

SPhD: What surprised you the most about him?

RK: Especially that, but let me think of something else. I was surprised by the stress and worry he experienced as he worked out the theory and saw how many people would want to attack it when he gave it to the world, and that comes out in the film.

SPhD: What do you think of the film?

RK: I think it’s wonderful. I’m so pleased that [director] Jon Amiel and [screenwriter] Jon Collee were able to shape the story the way they did, and get Paul Bettany and Jennifer Connelly, wonderful actors. In particular, I am particularly pleased about the way they linked Darwin’s interactions with Annie as an infant to those with Jenny the Orang[utan]. Paul Bettany was able to relate to the infant, and to the orang, just as Darwin did. He was just following Darwin. He wasn’t acting, he was just [being] a sensitive, engaged human.

SPhD: What was the importance of [Darwin’s orangutan] Jenny?

RK: Very few people paid attention to her until I found this comparison with Annie. This picture was in the British Library. The strange thing about Jenny was everyone went to the zoo to see her, because no-one had ever seen such a human creature. They hadn’t seen the great apes, they hadn’t seen chimpanzees, they just didn’t know they existed. Almost everybody found it distasteful. The young Queen Victoria came to the zoo to see this big sensation, and she went back to Buckingham Palace and wrote in her diary: “How painfully, and disagreeably, human.” So the young Darwin saw her, and while everybody else was pained, he saw her and he loved the link that he saw.

SPhD: Why do you think we’re still arguing about evolution?

RK: Because the point about our common nature with animals is so challenging and so unwelcome to people who want to think we’re special, we have special favor given by our maker and all that. I think that’s the crux, it’s our thinking about ourselves. I don’t really believe it’s a worry about the literal truth in the book of Genesis. Many many Christians have no trouble reconciling the biblical account of creation with the Darwinian one. Why people were upset by the Origin, I think, is mainly because it suggested to us that we have a common nature with animals. Darwin wrote a second book called The Descent of Man. In his first book On the Origins of Species he said nothing about human evolution, even though there was a clear indication of it, and didn’t publish the second until ten years later, after people had come to see the value of his idea.

SPhD: What did you find you personally related to about Darwin?

RK: I related to his passion about his theory, and his worries about it. If I had the extraordinary fortune to have his idea, and have the responsibility of offering it to everyone else, knowing the response I’d get, I can see how I’d be terrified by it, as he was. I admire him for his bravery.

SPhD: Describe Darwin’s relationship with his deeply religious wife Emma.

RK: He loved her deeply. He wanted to give her all the support and everything that he could. The relationship was for periods of their lives very difficult, because they couldn’t find common ground on these issues of faith and truth: her Christian faith, his scientific truth. But she kept him alive, he was very ill for most of his life with the stress. She protected him from people like Hooker and Huxley who wanted him to reveal his theory. She made this great sacrifice, because he meant more to her than anyone else, and that’s the truth of it. It was a wonderful story, how they found each other, how they loved each other, how she supported him, and how grateful he was to her.

SPhD: What do you think ultimately compelled him to publish? The film touches on a few different moments, but what put him over the edge?

RK: He thought it was profoundly important that people should realize where we came from, how we were part of natural life. He was also very ambitious. He saw the extraordinary power of the idea. People have said it’s unique in how such a simple insight explains so much. Evolution by natural selection explains, not just the origin of life, but the development of it as well. He wanted the pride and the pleasure of giving it to the world, and the delay was just the other side of the coin, I’m gonna say flack. If it stands up, eventually, it’ll all be praise. It’s still not all praise.

SPhD: If Darwin could be any animal, what would he be?

RK: I think he’d love to be a moth, feeding on beautiful plants with his tongue. Taking the pollen from them and putting it into another plant and enabling them to evolve. That was one of the processes he thought was miraculous.

SPhD: How about you?

RK: I’d like to be a condor.

SPhD: You fancy yourself a carrion feeder?

RK: Oh yes. Well, when [John James] Audubon first met the condors he wondered how on earth they found the carrion, the corpses that they lived on, while they were high up in the Andes. He wondered, could they be smelling at that distance, or could they possibly be seeing it? So he took a group of Turkey Buzzards and put some flesh in a paper bag, so you could smell it, and drove it past a group of Turkey Buzzards: no reaction. Then he took the corpse out of the bag, immediate excitement. So when Darwin got to the Andes, he repeated Audubon’s experiment with real condors, and it was clearly sight for them too. I just loved that.

SPhD: Your Wikipedia entry describes you as a conservationist. What are you interested in conserving?

RK: I’m going to change my answer to that last question. I would like to be a giant tortoise on Galapagos, because they have wonderful food—

SPhD: –No corpses?

RK: –Right, and they eat it in total safety, and have a very restful and pleasant life on beautiful islands. They are under such threat, because everybody wants to go see them and when you bring humans to an ocean archipelago they bring diseases and other impacts. I think Galapagos is a treasure for humanity, it shows us what Darwin saw, and shows us how the animals and plants have evolved.

SPhD: Would Darwin support Conan O’Brian or Jay Leno?

RK: Ah, I know something’s going on, is it competition for their timeslots? Is Jay more pugnacious then? I think I know Jay Leno, I don’t know Conan, so, survival of the fittest eh?

SPhD: Ruthless.

RK: But you asked who Darwin would support. He recognized that the fittest survive, but he always had a sympathy for the losers. Don’t say loser. The underdog. Darwin’s for Conan.

Stephen Compson studied English and Physics at Pomona College. He writes fiction and screenplays and is currently working toward a Master of Fine Arts at UCLA’s School of Theater, Film & Television.

~*Stephen Compson*~

***********************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development.

Follow us on Twitter and our Facebook fan page. Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.