“The fewer the facts, the stronger the opinion.” —Arnold H. Glasgow, American humorist

In today’s modern, fast-moving world, large telecommunication and media corporations are playing an ever increasing role in shaping the collective consciousness of society. This development might lead us to ponder what role, if any, traditional pillars of learning such as law, science, medicine, literature and art have to contribute to society. How does society absorb these contributions during the ongoing media (and social media) blitz that has transformed how we obtain, process and share information. More importantly, what influence do these contributions have upon society, and what influence does society reciprocate upon these institutions? For our last (and best) post of Science Week, ScriptPhD.com examines the relationship between science and society, and extrapolates social policy and pop culture lessons that could shape and transform that relationship in the future. Please click “continue reading” for more.

Science and Society Influencing Each Other: Nuclear Power

As one examines how modern scientific discovery has affected society in the 20th (and now 21st) Century, no area has had more sociopolitical ramifications than nuclear power. During World War II (1939-1945) scientific advancements in physics led to the development of the first atomic bombs. Their subsequent use helped end the war in the only such use of the weapon in conflict to date. Since the use of two atomic bombs by the United States of America, strongly disapproval has grown of the use of these atomic weapons. The discoveries made during the then-covert scientific team codenamed The Manhattan Project, led by Dr. J. Robert Oppenheimer, ultimately harnessed nuclear power as a plausible alternative source of energy. In France, for example, nuclear power provides over 75% of the country’s energy needs. The United States attempted to expand use nuclear power more broadly decades ago until 1979, when a tragic accident at Three Mile Island occurred. Fears and distrust of both the nuclear power industry and the United States’s nuclear regulatory body, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) reached a tipping point. As a result, people didn’t want a nuclear power plant in their backyard, and the building of nuclear plants came to a virtual standstill. The remaining nuclear power plants which would have been built faced fierce opposition by the local and surrounding residents near the facilities.

The confluence of modern events have considerably changed the equation in the decades since. The United States’s involvement in two wars in Iraq, soaring oil prices, a greater public awareness of global warming, and the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression have all combined to influence government

and policy-makers to try nuclear power again. President Obama recently granted more than $8 billion in Federal loan guarantees for two nuclear power plants to be built in Georgia and confirmed his steadfast support of nuclear power as a source of energy. Prior to this, the NRC granted the first license in over 30 years for the construction of a new nuclear power facility in 2006. Despite these developments, environmental and nuclear opposition groups have highlighted the very obvious problem of radioactive waste disposal from nuclear power plants. The future of nuclear power will depend on the interplay of science, technology, policy and how society processes them.

Science Benefiting Society: The LASER

Numerous applied scientific discoveries have benefited society in a transformative way via a single product or invention: the telephone, the computer, the internet and, most significantly and ubiquitously, the laser, which has often been called “a solution looking for a problem.” The laser (Light Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation) has garnered no less than five Nobel Prizes in Physics for science discovery and benefits to society. Albert Einstein first theorized about the laser in 1917 in a paper entitled “On the Quantum Theory of Radiation”; it would take 30 years before scientists would prove his laser theories were true! It would take even an even longer amount of time before the many benefits of the laser were realized and applied. The laser has been indispensable to a variety of fields such as medicine (treating skin cancer), entertainment (CDs and DVDs), telecommunications (optic fibers for broadband information delivery), scientific research (mass spectrometers, NASA Laser Sensing Technologies for outer space, and the mother of them all, the National Ignition Facility, to name just a few).

Through the Looking Glass: The Public, Scientists, Perception, and the Media

As in the above examples, it may be relatively straightforward to illustrate how science benefits society or how science and society may impact each other. What is more nebulous is the following: how does society view the scientific establishment as a whole, how do scientists view the public, and does the media influence society with its portrayal of science?

The Pew Research Center for the People and the Press, an independent, non-partisan public opinion research organization, collaborated with the American Association for the Advancement of Science, the world’s largest general scientific society, to publish a 2009 study examining a variety of attitudes towards science. As a profession, “scientist” was ranked third when the public was asked which profession contributes to society’s well being. This trend has been supported in the by the 2004 Harris Poll of most respected professions, which reported that “scientist” ranked first. While the public highly respects the scientific community, however, the study found a lack of reciprocation from scientists towards the public. When scientists were asked “What are some of the problems faced by science,” a staggering 85% believed the public didn’t know very much about science. Initially, one might think a scientist is inherently biased in their response to that question. After all, they have a PhD, ergo expertise, in a scientific field, so naturally, anyone with less knowledge than themselves might be deemed as a person who “doesn’t know very much about science.” Their conclusion is buoyed by a 2010 Science and Engineering Indicators study published by the National Science Foundation, that concluded: “Many Americans do not give correct answers to questions about basic factual knowledge of science or the scientific inquiry process.”. This is a continued source of concern and discussion when it comes to funding schools in the areas of science, technology, engineering and math. President Obama has renewed executive commitment to these areas in the form of the Educate to Innovate initiative, announced in late 2009, that aims to encourage and fund study of science, technology, engineering and math in primary and secondary schools.

The Pew study also found 76% of scientists believed the news media didn’t differentiate between good, solid scientific findings, and findings which were not well supported. This is corroborated by a recent Columbia Journalism Review paper lambasting the media’s accuracy and irresponsibility in the reporting of science during the H1N1 flu crisis. If the scientists are correct in their beliefs, this is a significant problem for our society. People depend on the news establishment, with a notably increasing reliance on the internet, to provide them fair, accurate and unbiased reporting. In addition, because science and technology impacts a growing part of our daily lives, it is particularly important that we receive accurate information. When participants of the NSF’s 2010 Science and Engineering Indicators were asked “Where do you get most of your information about current news events,” 47% responded with television, 22% with the internet, and 20% relied on newspapers as their primary source for news. Though the respondents listed these sources as their primary means of news, in fact, many people obtain news from a concomitant variety of sources, as opposed to selecting only one type of media (TV, internet, newspapers, radio). Forty-eight percent of scientists also believed the media was simplifying scientific findings. Lastly, 49% of scientists believed a major problem for science is “the public expects solutions to problems too quickly.” In a fast-paced, wired society where quick returns are expected (and demanded!), such a belief is not unexpected.

At times, certain types of science, which we will discuss in more depth below, reach the national, and even the world consciousness. In these cases, the discussion of the science itself transcends beyond the laboratory and enters into the realm of society’s popular consciousness in the form of politics, values and lifestyle. As a result, the discussion is transformed from one of science into one of local, state, national policy, and even international policy. When this occurs, the voice of the scientific community is only one factor in the policy decision making process. A society’s collective morality, risk assessment, and value judgment all play a role in shaping policy and, accordingly, science. Social discussion can have an enormous amount of influence on science. An excellent example is the emerging biomedical research area of human embryonic stem cell research, a field still in its infancy. In 2001, after important and considerable national debate at all levels, President George W. Bush banned all federal funding for the creation of any new human embryonic stem cell lines, but allowed researchers to continue their work with the then-existing stem cell lines. As a direct result of this policy, the citizens of California voted in 2004 for a $3 billion program (the California Stem Cell Initiative to publicly fund stem cell research. In addition, some universities began to form their own private foundations for stem cell research. Popular support for human embryonic stem research had changed considerably since President George W. Bush was in office, reaching majority support by the time Senator Barack Obama became the president and lifted the ban. According to the NSF’s 2010 Science and Engineering Indicators report, in 2002 only 35% of the public was in favor of stem cell research, compared to 58% in 2008.

This well-made 2007 video explores the moral/ethical debate of stem cell research, along with the difference between adult and embryonic stem cells:

Despite some of the schisms between public and scientific perceptions of each other, the overwhelming majority of Americans (84%) feel science benefits society. The Pew study also reported some important areas of agreement. When the public was asked to name areas that science has benefited society, 52% mentioned medicine and the life sciences as significant contributions to society, while only 7% of respondents mentioned telecommunications and computers. In line with the public, 55% of scientists acknowledged medicine and the life sciences as the most significant achievements.

Entertainment, Media and Social Influence: Jurassic Park and the CSI Effect

Does the entertainment industry influence society about science? It depends on who you ask, and what type of influence you were asking about. In an academic paper entitled Communicating Health Information Through the Entertainment Media, ER medical advisor Dr. Neal Baer argues that viewers retain a remarkable percentage of messages through medical show plotlines, and have a responsibility to address key issues facing the global population, such as cancer and HIV screening. In another academic paper entitled Simplifying Science: Effects of News Streamlining on Scientists’ and Journalists’ Credibility, Dr. Jacob Jensen of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign shows a strong ability to sway public perception of both science and scientists depending on how it portrays research data and findings. It’s clear that media, movies and television make science memorable to the public, but to what degree do they influence them?

Scientists have used a type of cloning technique called “nuclear transfer” to clone frogs in 1958, and sheep and cattle in the 1980’s, all using embryonic cells. Nuclear transfer is a technique of putting a donor nucleus (the portion of a cell which contains the DNA) into a donor cell which has had its own nucleus removed. Despite these genetics feats, the word “cloning” wasn’t exactly widely used by the public or the media—until 1993, when Michael Crichton’s 1990 science fiction book Jurassic Park was released as a summer blockbuster.

Jurassic Park is about a team of scientists on an island who successfully isolate dinosaur DNA from an insect preserved in amber. The dinosaur DNA is “cloned” into some amphibian DNA, and presto, “cloned” dinosaurs are revived out of extinction on the island. It wasn’t long after the movie was released for people to casually drop technical scientific cloning jargon like the actors in Jurassic Park. Never mind that much of the film’s science isn’t technically possible. It would only be three more years before we would be introduced to a sheep named Dolly—a clone created using nuclear transfer with, for the first time ever, adult stem cells. The news of Dolly spread like wildfire across the world, and a rich and vibrant debate on the ethics of human cloning began. As a result, 15 states in the United States have laws banning human cloning. There are no federal human cloning laws at this time.

* * *

Ask any defense lawyer or trial lawyer if they’ve heard of the CSI Effect, and they’ll answer in the affirmative. Ask them if there is any definitive proof for the CSI Effect in the courts, and the answer becomes a bit more muddled. The CSI Effect is an alleged direct impact on the Unites States court system from interest in the popular fictional CSI television franchise, and the many other forensic science-oriented entertainment programs that it spawned. The fictional CSI entertainment reveals how forensic science is used to catch and convict criminals. In the late 1980s, the U.S. legal courts were just beginning to allow the use of DNA and blood type tests as forensic evidence in court cases. November 1987 was the first time a person in the U.S. was convicted of a crime using a DNA test as evidence. As the technology became less expensive, and the legal system saw the value of such evidence, the use of this forensic evidence became more widespread.

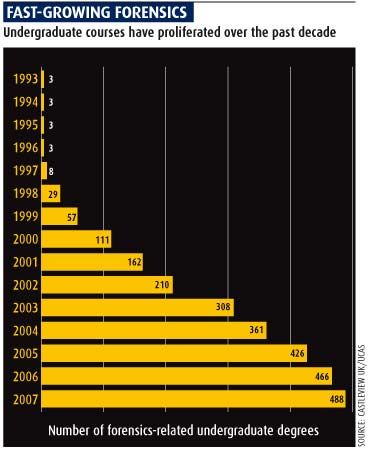

After a decade of CSI and other forensic-themed shows, a significant segment of society feels it knows a fair amount about forensic science and how such evidence is used in the courts. In this fabulous, must-read New Yorker piece entitled Annals of Law: The CSI Effect, law writer Jeffrey Toobin explores the good, the bad and the inaccurate about the effect, from the perspective of both the criminal justice system and the scientists it places a burden on. This is compounded by increased enrollment in forensics degree programs, which has measured exponential growth directly as a result of CSI (see picture on the left). Some trial lawyers feel the so-called CSI Effect places an unfair burden on them by increasing the threshold or level of expectation by which juries expect to see irrefutable proof of a crime, along with the DNA evidence to substantiate it. Defense attorneys feel it causes juries to believe forensic evidence is absolute, and can rarely, if ever, be wrong. (Several examples that this is not the case can be found here, here and here.) The truth is that while some of what CSI portrays is rooted in reality, in many cases the science shown is not accurate (terrific article from Popular Mechanics debunking the many CSI myths can be found here). Rarely does CSI show the numerous errors that commonly occur in a laboratory. In real life, these errors may go unnoticed until a trial, when the opposing side’s expert questions the validity of the method and/or the lab’s findings. Even some of the scientific techniques are portrayed to happen in a significantly shorter amount of time than what is really the case. This is, after all, entertainment. While there is a considerable amount of opinion regarding the CSI Effect, the jury is still out regarding both its existence and what, if any, ramifications there are from it.

NeuroScribe obtained a BS in Biology, and a PhD in Cell Biology with a strong emphasis in Neuroscience. When he’s not busy freelancing for ScriptPhD.com he is out in the field perfecting his photography, reading science policy, and throwing some Frisbee.

~*NeuroScribe*~

*****************

ScriptPhD.com covers science and technology in entertainment, media and advertising. Hire our consulting company for creative content development.

Follow us on Twitter and our Facebook fan page. Subscribe to free email notifications of new posts on our home page.